Abstract

Today, physician-assisted suicide and/or euthanasia are legal in several European countries, Canada, several jurisdictions in the United States and Australia, and may soon become legal in many more jurisdictions. While traditional Hippocratic and religious medical ethics have long opposed these practices, contemporary culture and politics have slowly weakened opposition to physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. Our chapter examines how assisted suicide and euthanasia have been presented in cinema, one of the most powerful influences on culture, by Nazi propagandists during the German Third Reich and by Western filmmakers since the end of World War II.

Almost all contemporary films about assisted suicide and euthanasia, including six winners of Academy Awards, promote these practices as did Ich klage an (I Accuse) (1941), the best and archetypal Nazi feature film about euthanasia. The bioethical justifications of assisted suicide or euthanasia in both Ich klage an and contemporary films are strikingly similar: showing mercy; avoiding fear and/or disgust; equating loss of capability with loss of a reason to live; enabling self-determination and the right-to-die; conflating voluntary with involuntary and nonvoluntary euthanasia; and casting opposition as out-of-date traditionalism. Economics and eugenics, two powerful arguments for euthanasia during the Third Reich, are not highlighted in Ich klage an and are only obliquely mentioned in contemporary cinema. One dramatic difference in the cinema of the two periods is the prominence of medical professionals in Ich klage an and their conspicuous absence in contemporary films about assisted suicide and euthanasia. A discussion of the medical ethos of the two time periods reveals how cinema both reflects and influences the growing acceptance of assisted suicide and euthanasia.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

10.1 Introduction

Anthony Trollope’s satirical, tragicomic novel, The Fixed Period, depicted a country with legislation forcing retirement at age 60 followed by a year of contemplation before a peaceful departure via chloroform (Trollope 1882). In 1905, American filmmakers screened Oslerizing Papa, a satirical film based upon William Osler’s facetious comments about the solution to the infirmities of old age proposed by Trollope (Pernick 1996, 139; Millard 2011). It was the first film about euthanasia, but it would not be the last.

Serious American silent films about euthanasia followed, such as Doctor Neighbor (1915) and Has Man the Right to Kill? (1915) before the release of The Black Stork (1915), a controversial film that played in theaters until 1942 about mercifully withholding life-saving medical care for infants born with congenital anomalies (Pernick 1996, 140). In 1936, recognizing the persuasive power of film, the Nazi government began making propagandistic documentaries, such as Dasein ohne Leben (Existence without Life) (1941), to “educate” health care workers about eugenics, sterilization, and eventually euthanasia. As public opposition to the secret euthanasia programs grew, German filmmakers turned their attention away from propagandistic documentaries toward commercial, feature films promoting euthanasia (Burleigh 1994, 202) such as Ich klage an (I Accuse) (1941), a melodrama whose justifications for euthanasia anticipated many contemporary films portraying the intentional ending of a patient’s life by a third party.

In this chapter, we will present the history of euthanasia during the Third Reich, describe contemporary physician-assisted suicide (PAS) and euthanasia legislation in the Western world, and explore the many similarities and few differences between the justifications in favor of euthanasia in Nazi and contemporary movies.Footnote 1

10.1.1 Terminology

To place our discussion of cinematic depictions of euthanasia in the proper context, we must discuss euthanasia during the Third Reich and at the present moment. To discuss this history clearly, a word about terminology for end-of-life decision-making is in order. While others have advocated a variety of alternative words and phrases, we adopt the terms that most simply and clearly describe the actions. Suicide refers to persons taking their own lives—undertaking actions with specific intention of making themselves dead. Assisted suicide denotes assistance in the act of suicide by another person or persons. When that other person is a physician, we adopt the simplest and most descriptive terminology, physician-assisted suicide (PAS). Others may use more equivocal terms such as death with dignity, physician-assisted death, physician aid in dying, and physician-assisted dying, all of which are compatible with a wide variety of actions that are not necessarily assistance in suicide and are, therefore, equivocal.

We use the term euthanasia to refer to intentionally ending the life of a person suffering from a medical illness, whether by a physician, other medical personnel, or anyone else. Some prefer terms such as medical assistance in dying to refer both to physician-assisted suicide and to euthanasia, but that term is, like the others discussed above, far too ambiguous, not only conflating the meaning of different death-hastening actions but also invoking other forms of care at the end of life such as the palliation of symptoms. The term euthanasia may be usefully subdivided into three categories. The first is voluntary euthanasia, which refers to the intentional termination of the life of a patient with decision-making capacity at the patient’s request. Nonvoluntary euthanasia refers to the intentional termination of the life of a patient who lacks decision-making capacity, such as a child or a mentally incompetent adult, with either parental, guardian, or family concurrence or the presumptive consent of the patient. Involuntary euthanasia refers to the intentional termination of the life of a patient who objects, or whose loved ones object.

Withholding life-saving measures (sometimes confusingly dubbed “passive euthanasia”) should not be confused with either PAS or euthanasia as we have defined these terms—in ethically appropriate cases of foregoing life-saving measures the intention is to end the treatment, not the life of the patient, even if death can be anticipated (Sulmasy 1998, 55–64).

10.1.2 Euthanasia During the Third Reich

In 1920, lawyer Karl Binding and psychiatrist Alfred Hoche wrote a short influential book The Permission to Annihilate Life Unworthy of Living. They argued that some lives were not worth living and promoted beneficent voluntary and nonvoluntary euthanasia for selected patients with incurable physical and/or mental disorders. Among their arguments in favor of euthanasia, two stand out. First, they argued that a higher morality should replace Western religions’ moral imperative to preserve life:

There was a time, now considered barbaric, in which eliminating those who were born unfit for life, or who later became so, was taken for granted. Then came the phase, continuing into the present, in which, finally, preserving every existence, no matter how worthless, stood as the highest moral value. A new age will arrive—operating with a higher morality and with great sacrifice—which will actually give up the requirements of an exaggerated humanism and overvaluation of mere existence. (Binding and Hoche 1920)

Binding and Hoche also dismissed longstanding Hippocratic ethical objections to euthanasia: “The young physician enters practice without any legal delineation of his rights and duties-especially regarding the most important points. Not even the Hippocratic Oath, with its generalities, is operative today” (1920).

While imprisoned in 1924 for his failed Munich putsch, Hitler read Menschliche Erblichkeitslehre und Rassenhygiene (Human Heredity and Racial Hygiene) by Erwin Baur, Eugen Fischer, and Fritz Lenz (1921), the holder of the first chair in eugenics in Germany. The ideas in this book may well have provided Hitler with the basic substrate for the strange concoction of eugenics, anti-Semitism, politics, and violence that led Lifton (1986, 27) to describe National Socialism as a “biocracy.” Hitler relied heavily on physicians to annihilate “life unworthy of life.” He told attendees at a 1929 Nazi Physicians’ League meeting that, if necessary, he could do without builders, engineers, and lawyers but that “you, you National Socialist doctors, I cannot do without you for a single day, not a single hour. If not for you, if you fail me, then all is lost. For what good are our struggles, if the health of our people is in danger?” (Proctor 1988, 64). In the same year, at the Nuremberg Party rally, Hitler praised Sparta’s policy of selective infanticide as a model policy (Welch 1983, 121).

Because physicians were pioneers, not pawns, in eugenics and euthanasia, they responded positively to Hitler’s flattery, incentives for academic and economic advancement, and opportunities to exercise power and gain prestige in his program of “Applied Biology” (Proctor 1988, 7). They willingly and enthusiastically chose to eliminate Jews from medicine, involuntarily sterilize nearly 400,000 German citizens to prevent transmission of their allegedly inferior genes, prohibit marriage and sexual relations between Aryans and non-Aryans, and, ultimately, murder nearly 200,000 people whose lives were considered not worth living.

The Nazi euthanasia programs began with an autonomous request directly from a family to Adolf Hitler to euthanize their child, Gerhard Herbert Kretschmar, who was blind, epileptic, physically disabled, and diagnosed as an “idiot”—it was approved (Schmidt 2002, 241–242). The Reich Committee for the Scientific Registration of Serious Hereditary and Constitutional Illnesses was created to secretly oversee the Children’s Euthanasia Program that claimed the lives of 5,000–7,000 children between 1939 and 1945 in 30 special children’s wards, most often by a nurse administering an overdose of tranquilizers (Hohendorf 2020a, 63–65).

The adult euthanasia program began in 1939 with the required registration of almost all patients in nursing homes and neuropsychiatric hospitals. The registration forms were sent to the recently formed Charitable Foundation for Institutional Care located at Hitler’s Chancellery whose address was Tiergartenstrasse 4, hence the name Aktion T4 for the adult euthanasia program. Three psychiatric experts reviewed the forms without examining the patients, and, together with the medical director of Aktion T4, initially psychiatrist Werner Hyde and, later, psychiatrist Paul Nitsche, selected which institutionalized patients were to be killed, primarily those deemed unable to do productive work and all Jews (Hohendorf 2020a, 65).

Patients selected for euthanasia were transported by the Charitable Society for the Transportation of the Sick from one transit institutions to another to obfuscate the program’s true purpose and to obscure the patients’ location from their families. Finally, the patients arrived at one of six killing centers in Germany and Austria where they were killed by physicians in gas chambers designed by physicians, chemists, and engineers according to Viktor Brack’s motto, “the syringe belongs in the hand of the physician” (Lifton 1986, 71; Sulmasy 2020, 229). Physicians then fabricated a cause of death for the death certificate that was sent to the patients’ families.

Significant public opposition to Aktion T4 arose after Clemens Count von Galen, the Bishop of Münster, addressed the issue of nonvoluntary euthanasia in an August 1941 sermon, which led to the end of the gassing but not the killing (Lifton 1986, 39). Some medical directors of institutions other than the six killing centers had already been starving their patients to death, and soon many more institutions were killing their patients by starvation, tranquilizers, neglect, exposure, and untreated infections in what was termed wild euthanasia (Hohendorf 2020a, 67). Nazi documents confirm 70,273 murders in the six killing centers, and the estimated number of murders during the period of decentralized euthanasia is between 90,000 and 130,000 (Friedlander 1995, 151–163).

The medical procedure for euthanizing large numbers of disabled persons in gas chambers became the preferred technique to implement “The Final Solution.” The bridge from gas chambers for eugenic euthanasia to gas chambers for mass murder was Operation (or “Special Treatment”) 14f13 (Lifton 1986, 135). Experienced Aktion T4 psychiatrists were enlisted to select “asocial” patients from concentration camps for “special treatment” in gas chambers at a euthanasia center, which “widened indefinitely the potential radius of medicalized killing” (Lifton 1986, 136). Thus, after considering several potential methods for the mass murder of Europe’s Jews, the Nazis chose gas chambers because “the technical apparatus already existed for the destruction of the mentally ill” (Proctor 1988, 207). Physicians like Josef Mengele, the “Angel of Death” at Auschwitz, selected and gassed many of the 4,500,000 Jews considered undesirable or useless.

10.1.3 Euthanasia in the Contemporary Western World

The United States was the world’s leader in eugenics prior to World War II, and Germany both learned from and surpassed the US in its zeal to catch up. For example, Germany patterned its 1933 Sterilization Law after Virginia’s model sterilization law, which the US Supreme Court declared constitutional in 1927 (Proctor 1988, 101). Germany modeled its anti-miscegenation and anti-Semitic Nuremberg laws on US Jim Crow laws (Whitman 2017). German racial scientists admired America’s restrictive eugenic immigration policies (Proctor 1988, 100).

Eugenics was also popular in Scandinavian, the Baltic states, and Switzerland (Roelcke 2020, 52). Eugenics and euthanasia, while not intrinsically linked, often go hand in hand (Roelcke 2020, 53). Article 115 of the Swiss Criminal Code of 1937 prohibits assisted suicide for selfish motives but permits it for altruistic reasons. This distinction was incorporated into a 1941 law permitting altruistic help to severely ill people seeking to end their lives, a law the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences did not support. Exit and Dignitas, membership corporations that currently promote assistance with suicide, were founded in 1982 and 1998, respectively (Hurst and Mauron 2003).

According to Eduard Verhagen, the co-author of the 2005 Groningen Protocol for Newborn Euthanasia in Holland, “It is probably fair to say that during the past decades, the Dutch have been ‘obsessed’ by death and dying, with the majority of the population in favor of euthanasia since 1966 in public opinion polls.” In the 1973 Postma decision, the Leeuwarden District Court convicted a doctor of “death on request” and sentenced her to one-week probation instead of a possible 12-year prison term. The physician had administered a lethal dose of morphine to her 78-year-old deaf and partially paralyzed mother who had repeatedly pled with her daughter to end her life (Sheldon 2007). In 1984, the Alkmaar case led the Supreme Court to introduce a potential legal justification for not prosecuting physicians who euthanize their patients. Thus, while euthanasia remained illegal in the Netherlands, courts did not prosecute doctors performing euthanasia or assisted suicide (Verhagen 2020, 91).

In 1990, the Remmellink committee investigated Dutch end-of-life practices and found hundreds of reported cases of euthanasia with very few prosecutions, many dismissals, and nearly 1,000 cases of “termination of life without an explicit request” (Lewis 2007). In 2002, the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act legalized euthanasia in the Netherlands under certain conditions for legally competent adults (16 years of age or older) and children 12–15 years of age making a valid request. Belgium and Luxembourg (Atwill 2008) passed similar legislation in 2002 and 2008, respectively. In Australia, voluntary PAS and euthanasia were implemented in Victoria in 2019 and are expected to begin in Western Australia in 2021 (End of Life Law in Australia, n.d.).

In general, the increasing number of deaths of terminally ill patients by PAS and euthanasia in the Netherlands and Belgium and, in particular, the increasing number of deaths by PAS and euthanasia among psychiatric patients who are not expected to die within the foreseeable future has heightened concern about “eligibility creep” in vulnerable populations (Dierickx et al. 2017; Evenblij et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2016, 362–368; Verhofstadt et al. 2019, 150–161). In 2015, Lerner and Caplan expressed unease about a slippery slope in the Netherlands and Belgium after one study reported data from a Dutch End-of Life Clinic in which some patients that were categorized as “tired of living” obtained PAS and euthanasia and another reported an alarming increase beginning in 2013 in the rate of euthanasia of Belgian applicants experiencing “tiredness of life” (Lerner and Caplan 2015, 1640–1641).

Until recently, there has been resistance to the legalization of PAS and euthanasia in Germany. However, on February 26, 2020, the German Federal Constitutional Court repealed the prohibition of “business-like” assistance with suicide, the type of assistance provided in Switzerland by Exit and Dignitas. Simultaneously the court ruled that physicians are not legally obligated to provide assistance with suicide, which accords with the German Medical Association’s rejection of both PAS and euthanasia. The future of PAS and euthanasia in Germany is uncertain. (Sahm 2020, 126–128).

Euthanasia is currently prohibited everywhere in the US. Two rulings by the Supreme Court of the United States, however, permitted individual states to enact PAS legislation while simultaneously denying a constitutional right to PAS (Vacco v. Quill, 521 U.S. 793, 1997; Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 1996). In 1997, Oregon became the first state to legalize PAS; it is now permitted in nine additional jurisdictions—Washington, Colorado, Hawaii, California, District of Columbia, Montana, Vermont, New Jersey, and Maine.

Not only is the number of states permitting PAS increasing, but there is also evidence of eligibility creep in the US. For example, in 2019, Oregon’s legislature considered including “a degenerative condition that will, at some point in the future, be the cause of the patient’s death” in the definition of a terminal disease in its Death with Dignity Act (Oregon Legislative Assembly 2019). If passed, this provision would greatly enlarge the number of patients eligible for PAS. Similarly, in Canada, in October 2020, three cabinet ministers reintroduced legislation to remove the requirement for a person’s natural death to be reasonably foreseeable in order to be eligible for medical assistance in dying (MAID) (Government of Canada 2020). In the Fall of 2020, the US-based and well-funded “Completed Life Initiative” produced a twelve-hour webcast which was characterized, without opposition or objection, as promoting the idea that persons without a terminal disease “may autonomously judge that their lives are complete, therefore no longer worth living, and may justifiably choose to make themselves dead with the sanction of the state and the assistance of the medical profession” (Completed Life Initiative 2020). This objective appears very similar to that of the Dutch and Belgian end-of-life clinics, and it seems likely that the US will eventually follow their lead unless there is a groundswell of serious opposition.

10.1.4 Why Film?

We have chosen in this essay to highlight the ways in which film presents assisted suicide and euthanasia. Understanding history is important, understanding the impact of culture on medical practice may be more important still. The medical ethos—the distinguishing character, sentiment, moral nature, or guiding beliefs of patients, health care professionals, medical organizations, or medical institutions—is derived from three interacting factions: medicine, culture, and government (Roelcke 2016, 183). In Western democratic countries, we contend that the cinema is one of the most powerful influences on culture, and therefore, is very influential in determining the medical ethos.

When filmmakers portray difficult bioethical questions, they tend to present dramatic narratives that seemingly offer credible solutions to insoluble problems, thereby providing audiences a measure of relief from the anxiety such questions provoke. These films present either relatively simple and satisfying personal solutions to complex and frightening bioethical issues the audience might one day confront in real life, or palatable (if improbable) political solutions by casting the protagonists as heroic champions of causes fought out in courts, popular referenda, or legislation. By having an appealing central character hold a film’s center of gravity, these melodramas also give viewers the impression that they, like the film’s hero, have the power within their autonomous selves to assert control and solve the complex problem presented in the film (Gabbard and Gabbard 1999, 3–34).

The powerful images created in films often stay with us and create a myth about how life ought to be or how we would like it to be. Think of Ali McGraw as Jenny, dying of leukemia at the end of Love Story (1970). Unlike most patients treated unsuccessfully for leukemia, Jenny remains articulate and beautiful right up to her tragic end. Improbable portrayals of illnesses can create problems for patients confronting a similar ailment. For example, films such as Ordinary People (1980) and Good Will Hunting (1997) can generate unrealistic expectations that affect patients’ attitudes toward their care (Gabbard and Gabbard 1999, 176–182). Of particular concern is the power of culture and of mass communications such as film to stimulate and increase the behaviors they portray, such as suicide. This well-documented phenomenon is known as the copycat or contagion effect (Coleman 2004, 217–235; Marzuk, Tardiff, and Leon 1994, 1813–1814; Marzuk et al. 1993, 1508–1510) or the Werther effect (Coleman 2004, 1–5; Kogler and Noyon 2018; Phillips 1974, 340–354).

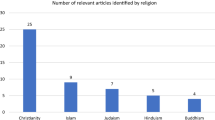

The subject of euthanasia has been treated in many contemporary films—at least 21 between 1971 and 2006—and Hollywood has responded favorably to cinematic versions of end-of-life decision-making, almost all of them promoting euthanasia (Gabbard 2010, 153–162). Three films, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), The English Patient (1996), and Million Dollar Baby (2004), received Academy Awards for Best Picture and three more, The Barbarian Invasions (2003), Mar adentro (The Sea Inside) (2004), and Amour (2012) won Oscars for Best Foreign Film.

10.2 Medical Films Under National Socialism

Hitler loved films and understood their persuasive power. In his 1925 autobiographical manifesto Mein Kampf, he wrote:

At most a leaflet or a poster can, by its brevity, count on getting a moment’s attention from someone who thinks differently. The picture in all its forms up to the film has greater possibilities. Here a man needs to use his brains even less: it suffices to look or at most to read extremely brief texts, and thus many will more readily accept a pictorial presentation than read an article of any length. The picture brings them in a much briefer time, I might almost say at one stroke, the enlightenment which they obtain from written matter only after arduous reading. (Hitler, 420; italics in the original)

The Nazi government coordinated and unified each and every aspect of German life into a single, hierarchical structure responsible to a vertical chain of command, a process known as gleichschaltung. For example, the Propaganda Ministry under the leadership of Joseph Goebbels was responsible for the Nazi propaganda campaign to secure the allegiance and collaboration of German citizens through any and all forms of mass communication (Kater 2019). Goebbels understood the power of cinema as a propagandistic tool as did leading bureaucrats such as Kurt Zierold who stated:

Propaganda as a means of coordinating the purposeful ambitions of a people naturally has to be designed for the masses because it cannot do without the instrument of suggestion. Propaganda for a small number of people is a contradiction in terms. Film as a product of the most modern technique, with its unlimited possibilities of copying, is by nature aimed at the masses. (quoted in Schmidt 2002, 59)

To secure the power of the cinema for propaganda, Goebbels drafted the Reich Film Law (Schmidt 2002, 63), which centralized control over all educational and medical films (Schmidt 2002, 127). Consequently, almost all independent educational film production companies were out of business by 1935 (Schmidt 2002, 81).

Because many physicians had been advocating eugenics and euthanasia for nearly three decades before Hitler came to power in 1933, they readily accepted appointments to a scientific advisory committee to evaluate and edit existing medical films and to oversee the production of new medical films (Schmidt 2002, 96–101). In addition to military training films such as Kampf dem Fleckfieber (Struggle Against Typhus) (1941/1942), propagandists produced films to promote eugenics (racial hygiene, or rassenhygiene, in Germany) and Social Darwinism, such as Erbkrank (Hereditarily Ill) (1936) and Alles Leben ist Kampf (All Life is a Struggle) (1937), both silent films. In 1936, Hitler requested a more polished and professional sound film endorsing eugenics, Opfer der Vergangenheit (Victim of the Past), and ordered it shown in all German movie theaters (Burleigh 1994, 183–202).

Filmmakers encouraged physician compliance with the 1933 Sterilization Law that led to the involuntary sterilization of nearly 400,000 German citizens with training films like Sterilisation beim Manne durch Vasektomie bzw. Vasoresektion (Sterilization in the Male by Vasectomy) (1937) for surgeons (Schmidt 2002, 137–173) and propagandistic educational films like Hereditary and Acquired Epilepsy (1935) and Wilson-Pseudosklerosis (Wilson’s Pseudo-Sclerosis) (1938) for neurologists, psychiatrists, and other medical personnel (Schmidt 2002, 196–208).

The approximately 200,000 victims of the Nazi children’s and adult euthanasia programs gave opportunistic medical researchers and filmmakers a chance to correlate clinical and cinematographic observations with pathological specimens obtained from patients previously identified with neuropsychiatric illnesses of interest. For example, in 1937, psychiatrist Gerhard Kujath, under the supervision of Karl Bonhoeffer, made a silent black and white film, A 41/2-Year-Old Patient with Microcephaly (1937), in which they conducted torturous medical examinations and experiments on Valentina Z. When the Children’s Euthanasia Program was established in 1939, Valentina Z was transferred to Berlin Wittenau, one of thirty pediatric centers for “special treatment” of children with disabilities—involuntary killing, usually by luminal. After many more additional experiments, Valentina Z was most likely killed on October 28, 1941, and immediately transferred to the Rudolf Virchow Hospital where research specimens were collected during her autopsy, including brain specimens collected by Dr. Kujath (Schmidt 2002, 249–262).

The leaders of the Children’s Euthanasia Program and Aktion T4, the adult euthanasia program, used these shocking documentaries to induct and indoctrinate medical subordinates into the system that killed between 5,000–7,000 disabled children and nearly 200,000 disabled adults. Then, in 1940, Dr. Paul Nitsche, the head of the adult euthanasia program, commissioned Hermann Schweninger to film institutionalized children and adults for sophisticated propagandistic documentaries about medicalized murder. These films would document the high cost of caring for neuropsychiatric patients in asylums, the extreme suffering of these patients and their families, the genetic measures such as sterilization and marriage counseling that could prevent the birth of the “incurable and life-unworthy,” and finally, the euthanasia program’s scrupulous selection process for “the course of action,” the killing of the patients (Burleigh 1994, 195–197).

Schweninger and a producer from Tobis Films, a German film production and distribution company, visited 20 to 30 asylums and shot about 10,000 m of film that were eventually edited into several versions of the educational film Dasein ohne Leben (Existence Without Life) and the 1942 scientific documentary Geisteskrank (Mentally Ill) (Burleigh 1994, 197–202). Film clips from Dasein ohne Leben showing some of these mentally and physically disabled patients can be seen on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (Special Collections 2001.359.1, n.d.) and in Michael Burleigh’s documentary Selling Murder: The Secret Propaganda Films of the Third Reich (1991).

Despite the Nazi’s best efforts to keep the details and the extent of their secret euthanasia programs from the public, opposition grew. Because he was unhappy about the public outcry, Heinrich Himmler, the main architect of the Holocaust, wrote to Victor Brack, the administrator of Aktion T4, to encourage public education about euthanasia through films (Reitlinger 1953, 132). Brack took the hint and persuaded Tobis Films to make commercial feature films both to give a compassionate and sound bioethical basis to their medicalized murder and to pave the way for potential legalization of “mercy killing.” A justificatory document from the filmmakers stated:

We were given the task of writing a script for a film about euthanasia, about the extinguishing of unworthy life. Because of the circumstances of the time, we became convinced that it was necessary to avoid everything which seemed like deliberate propaganda, but also everything which hostile opinion could construe as a threat emanating directly from the state. In our film we have let the dictates of the heart speak in the belief that this will pave the way for the dictates of the law. (Burleigh 1994, 202)

Schweninger produced three feature films. The epigraph for the first film, a fitful romance entitled Drei Menschen (Three People) (1941), was Nietzsche’s dictum: “What causes more suffering in the world than the stupidity of the compassionate?” The second film, The Foreman (1941), which included a final courtroom scene with ethical and legal arguments in favor of euthanasia, was bad enough that Wolfgang Liebeneiner, an up-and-coming director that Hitler’s chancellery brought in to make a feature film about euthanasia, avoided making it (Burleigh 1994, 205).

Schweninger chose Ich klage an for his third film, an adaptation of a 1936 novel Sendung und Gewissen (Vocation and Conscience) written by ophthalmologist Helmut Unger, a participant in Aktion T4 who had already written 50 fiction and nonfiction works including one used by Tobis Films as the basis for its biopic on Robert Koch. When the book and Schweninger’s original treatments proved unsatisfactory for the film project, Liebeneiner met with Victor Brack, Hans Hefelmen, and Dr. Paul Nitsche, leaders of Aktion T4. After discussions with a neurologist, Liebeneiner concluded that the film’s female lead should have multiple sclerosis (MS). Harold Bratt, Tobis’s chief dramatist, developed the storyline of the script: “Two doctors love a woman. She marries one of them. As she falls ill with multiple sclerosis, she asks one of them to kill her. Her turns her down. Thereupon she asks the other, who does her bidding. A trial results, in which the case is discussed” (Burleigh 1994, 210). Bratt’s storyline was then developed into a script by Eberhard Frowein (Herzstein 1987, 307; Romani 1992, 108). The film was released on August 29, 1941, a week after Hitler ended the secret mercy killings in gas chambers at the six euthanasia centers (Waldman 2008, 227).

10.3 Euthanasia in Ich klage an and in Contemporary Cinema

We will compare the arguments in favor of PAS and euthanasia presented in Ich klage an and in contemporary cinema. We focus on Ich klage an because it is the archetypal, best, and most popular Nazi propagandistic, commercial, feature film promoting euthanasia. Its explicit and implicit arguments will be identified and compared to those presented in one or more contemporary films that showcase similar if not identical arguments.

Because film is primarily a visual medium, we recommend that readers watch Ich klage an (available on Amazon with English subtitles), the six contemporary Oscar-winning films that promote euthanasia, and Michael Burleigh’s documentary Selling Murder, which has clips from rarely seen Nazi euthanasia films like Daisen ohne Leben (Burleigh 1991). While other authors have written (Burleigh 1994; Pernick 1996) and spoken (Gabbard 2016) eloquently about Ich Klage An and contemporary cinema, they did not focus on their bioethical arguments.

Ich klage an is strikingly different from the Nazi euthanasia documentaries. It contains almost no references to Nazism and has the look and feel of a contemporary melodrama. As Michael Burleigh puts it: “Apart from the fact that the judges have Nazi emblems on their robes, and that the jury chamber is adorned with a modest bust of Hitler, the film could just have well been set in the 1950s as in the 1930s” (Burleigh 1994, 215).

To encourage as large an audience as possible to view the movie, the filmmakers recruited well-known actors for the lead roles, including Heidemarie Hatheyer as Hanna Heyt, the bubbly, attractive, and intelligent wife who contracts MS, Paul Hartmann as Professor Thomas Heyt, her academic physician/scientist husband, Matthias Wiemann as Dr. Bernhard Lang, her former paramour who is now her friend and very conscientious general practitioner caring for her, and Christian Kayssler as the presiding judge at the murder trial. Hatheyer, in particular, was one of the premier actresses of German-speaking cinema (Romani 1992, 103–110). Adding the engrossing medical and courtroom dramas, skilled camerawork, and popular composer Norbert Schultze’s moving score to the fashionable but formulaic triangular love story yielded an effective and popular melodrama that was seen by 15.3 million Germans (Burleigh 1994, 216).

10.3.1 Cinematic Justifications of Physician-Assisted Suicide and/or Euthanasia

We suggest that there are at least eight bioethical justifications for PAS and euthanasia that have been presented through the medium of film: (1) showing mercy; (2) avoiding fear, disgust, and prioritizing the quality of life; (3) equating of lost capability with loss of a reason for living; (4) allowing self-determination and rights; (5) conflating voluntary with the involuntary and nonvoluntary euthanasia; (6) casting all opposition as out-of-date traditionalism; (7) avoiding the financial toll of terminal illness, or economics; and (8) preventing the transmission of undesirable genetic traits, or eugenics.

Ideally, we would also discuss and compare contemporary feature films that are even marginally opposed to assisted suicide and euthanasia, but very few such films have been made. Those few include the romantic fantasy Just Like Heaven (2005), Dr. Cook’s Garden (1971), a rarely seen made-for-television movie, some documentaries like How to Die in Oregon (2011), and, possibly, the ambiguous Miele (Honey) (2013).

10.3.1.1 Mercy

A popular justification for legalizing PAS and euthanasia is that it is the kind and merciful thing to do for someone in pain. Popular anecdotes abound regarding dying persons writhing in pain and begging to be killed while cold doctors are either absent or stand by and do nothing, claiming that to help the patient would be a violation of the Hippocratic Oath. This presentation is, of course, a complete caricature, but it makes for wonderful melodrama. The suffering of the sick is also sometimes presented as more existential than physical, but the argument is always that euthanasia is an act of mercy, and, erroneously, that there are no alternatives.

In Ich klage an, during a break in the trial of Dr. Heyt, the jury discusses the case and one juror says, “There must be proof that [Hanna Heyt] stated an express wish to die.” When another juror responds, “And then?”, the first juror says, “It would be mercy killing, not murder.” Earlier in the movie, we see a research colleague of Dr. Heyt euthanize a mouse with disabilities similar to Hanna’s by pouring the fatal liquid into a beaker filled with cotton balls. As she places the mouse into the beaker and covers it, she says, “Poor animal. I haven’t forgotten you. There. Soon you’ll feel no more pain.”

Immediately following this doctor’s clear expression of mercy for the “poor animal,” the scene fades to a closeup of the hands of Hanna’s doctor and friend, Bernhard Lang, as he, too, pours liquid morphine into a glass container. Hanna, who appears to be in physical pain, asks him to leave the bottle, saying, “Promise me that you’ll help me when I am [that sick]. Promise me that you’ll spare Thomas and me.” If the doctor’s mercy is good for the mouse, why not for the beloved friend?

Lang denies her request: “I’m your best friend. But I’m also a doctor, and a doctor is a servant of life.” A few scenes later her husband Thomas also refuses her request to “help” her if she gets worse because he is hoping his research will quickly yield a cure. When it becomes clear that he will not find a cure, Thomas surreptitiously administers the entire bottle of morphine to Hanna who dies as peacefully and calmly as only an actor can do in a movie with great camera work and beautiful background music. Thomas then leaves her room, tells Bernhard what he has done, and an argument ensues between the two doctors:

- Bernhard.:

-

She asked me, too, but because I love her, I didn’t do it.

- Thomas.:

-

Because I loved her more, I did it. Because her suffering was inhumane, because man must be above death, that’s why I set her free.

In Mar adentro (The Sea Inside), based on a true story, the central character Ramón Sampedro (Javier Bardem), who is quadriplegic, echoes Thomas’s declaration about love and mercy. Ramón tells Rosa, a woman who loves him, “Don’t burden me with your love. The person who actually loves me will be precisely the one who helps me die. That’s loving me.”

Inadequate relief of physical pain is presented as a primary problem in The Barbarian Invasions, leading the main character’s son to illegally obtain heroin for Rémy, his father, who is dying from cancer. A nurse eventually administers an intentionally fatal dose of heroin, and Rémy dies in a bucolic country house surrounded by his loving family. Similarly, Count László de Almásy (Ralph Fiennes), the protagonist in The English Patient, receives multiple daily injections of narcotics, presumably to relieve the physical pain he experiences as a result of the extensive, disfiguring burns he received when his airplane was hit by gunfire.

While inadequate relief of physical pain features in both these films, inadequate relief of psychological pain is a much more common argument in favor of PAS and euthanasia in the cinema. In Ich klage an, for example, Hanna is dying of MS and her course is characterized more by suffering from what she is unable to do, even though she does fall and suffer some physical pain. In actuality, the data from patients requesting PAS in Oregon supports the prevalence of psychological over physical rationales for PAS requests. Of the nine most common reasons offered by patients for the request, illness-related experiences—feeling tired, weak, and uncomfortable and loss of function—ranked first and second while physical pain ranked only seventh. Loss of sense of self, desire for control, fears about future quality of life and dying, and negative past experiences with dying ranked three to six in almost as high percentages as the illness-related experiences (ProCon.org 2018). While the public may believe otherwise, today most patients’ physical pain at the end of life can be relieved by competent palliative care professionals (Quill 2020, 160).

Miele (Honey), an Italian film, addresses the issue of psychological pain directly. It features a young woman, Irene, known as Honey, who assists in the suicide of terminally ill patients by providing fatal doses of illegally obtained barbiturates. She then discovers that one client, Grimaldi, is not sick. He is simply tired of living and wants to die. An argument ensues about why he wants to die:

- Grimaldi.:

-

Is there a list of acceptable reasons? Would you rather I told you I have a terrible secret, a crime to atone for? I don’t owe you an explanation. You sell, I buy.

- Honey.:

-

That’s not exactly the case. I help. But not people like you, you can live…

- Grimaldi.:

-

For all I know, not all your clients are on the verge of death…Believe me, I’ve lost interest in everything. It’s all so boring and insignificant. I can understand, it’s easier to help the terminally ill. Nobody can stand the sight of a body falling apart. It’s natural to feel pity then. But if the illness is invisible, then what? Is it just a whim, heresy? This thing you do for money, everybody should be able to do it. The sick don’t have more rights than me.

Honey struggles with her next assisted suicide, visits Grimaldi again and again, and eventually stops providing her special services, telling him, “Nobody really wants to die. None of these people I assisted in these three years wanted to kill themselves. They want to live. They all want to live. But they no longer can call it a life. They can’t take it anymore … I can’t do it anymore.”

In the end, Grimaldi appears to commit suicide, possibly with the barbiturates Honey had initially left with him. The ambiguous ending corresponds with the situation in Italy where PAS and euthanasia were illegal until Italy’s top court issued a ruling in the 2019 prosecution of euthanasia activist Marco Cappato who accompanied Italian disc jockey Fabiano Antoniani, or DJ Fabo, to his death at Dignitas in Switzerland in 2017. In October 2018, the court suspended proceedings and gave the Italian parliament one year to address assisted suicide, which it did not do (Schiavi 2018). The court, therefore, ruled that assisted suicide could be legal when a patient’s irreversible condition is “causing physical and psychological suffering that he or she considers intolerable” (EuroNews 2019).

The ruling came a week after Pope Francis told a delegation from the Italian Doctors Order, “We can and we must reject the temptation, which is also favoured by legislative changes, to use medicine to satisfy a sick person’s wish to die” (EuroNews 2019). He also quoted his predecessor Pope John Paul II, “Every doctor is asked to commit himself to absolute respect for human life and its sacredness” (BBC News 2019).

Cinema also reflects and promotes cultural trends undermining the idea that human life has special value. When asked who they would save, their drowning dog or a drowning stranger, more than two-thirds of high school students would save their drowning dog (Prager 1990), and over 25 percent of medical students at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev hesitated in choosing the human over the animal (Glick 1995). This blurring of the distinction between humans and animals, promoted by well-known public intellectuals such as Peter Singer and Cass Sunstein, leads to the idea that acts of mercy toward animals, especially pets, are ethically equivalent to those same acts toward humans, especially at the end of life (Singer 1977; Sunstein and Nussbaum 2004). In fact, such principles of equality and justice would seem to make them required. For example, the president of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies advocates euthanizing humans just as we do our beloved pets in her article entitled “Love Thy Neighbor as Thy Dog” (Davies 1991).

In Ich klage an, during a break in the trial, one juror presents the common argument of showing mercy toward pets: “…just a few weeks ago I had to give my old hound the mercy shot. He was blind and lame, but otherwise, he had faithfully served me his entire life. And if a hunter doesn’t do that, then he’s a harsh fellow, not an honorable huntsman.” Another juror says, “Yes, but those are animals,” to which the first juror responds, “Yes, but are people to be treated worse than animals?”.

Harrison, the quadriplegic protagonist in Whose Life Is It Anyway? (1981), makes a similar argument to the judge: “Your honor, if you saw a mutilated animal on the side of the road, you’d shoot it. Now, I am only asking for the same mercy that you would show that animal.”

Million Dollar Baby makes the same argument. Early in the movie, before she becomes quadriplegic, Maggie visits her hometown with Frankie, a father figure as well as her trainer. While there, she realizes that her family is disreputable, did not support her in the past, and never will. She relates a story to Frankie about her dead but idealized father:

- Maggie.:

-

You ever own a dog?

- Frankie.:

-

Nope. Close as I ever came was a middleweight from Barstow.

- Maggie.:

-

My daddy had a German Shepard, Axel. Axel’s hindquarters were so bad he had to drag himself room to room by his front legs. Me and [my sister] Mardell’d bust up watchin’ him scoot across the kitchen floor. Daddy was so sick by then, he couldn’t hardly stand himself, but one morning he got up, carried Axel to his rig and the two of them went off into the woods, singing and howling. Wasn’t till he got home alone that night that I saw the shovel in the truck. Sure miss watchin’ the two of them together. I got nobody but you, Frankie.

Later, when she is lying in bed, quadriplegic on a respirator, and just before her soliloquy and her request of Frankie to euthanize her, Maggie reminds him of that story.

- Maggie.:

-

I got a favor to ask you, Boss.

- Frankie.:

-

Sure, anything you want.

- Maggie.:

-

Emember what my daddy did for Axel?

- Frankie.:

-

Don’t even think about that.

- Maggie.:

-

I can’t be like this, Frankie…

10.3.1.2 Fear, Disgust, and the Quality of Life

It is sometimes argued, to this day, that euthanasia is necessary because the quality of a person’s life can be so low that no reasonable person would want to continue to live that way. Such cases typically involve severe physical deformities or neuropsychiatric conditions. Alzheimer’s disease, for instance, is depicted in its late stages in medical films designed as aids for advance care planning (Volandes et al. 2009). The films present patients who are bedbound, incontinent, tethered to feeding tubes, unable to recognize relatives, screaming out in pain, and/or delirious. At the other end of the lifespan, children with deformities are depicted by pro-euthanasia activists as monsters or vegetables in ways that alarm, frighten, or disgust us. The argument for euthanasia for these conditions may be rooted in fear and disgust, but it is rationalized by describing such individuals as not having “interests,” and so their deaths are not accounted as murders (Singer 1993, 160–169).

In Ich klage an, when Hanna asks Bernhard to assist with her death, she says, “You know, I am not afraid of dying but I don’t want to just lie there for years, not being human, but only a lump of meat. It would be torment for Thomas if I deteriorated like that.” When Hanna asks Thomas to assist with her death, she says, “You must help me remain your Hanna to the very end, before I turn into something else, deaf, blind, or demented. I couldn’t bear that…Promise me, Thomas, that you’ll release me before that. Do it Thomas, if you really love me. Do it.”

Contemporary discussions of Ich klage an pay too little attention to the subplot of the reversal of fortunes of the little girl with meningitis whom Bernard saves from death and its relevance to the arguments in favor of euthanasia. In a follow-up visit with a colleague, Bernhard asks, “Where is she now?” The colleague responds, “In an institution. She’s blind, she’s deaf, too, and demented. Wonderful, you healed her, Doctor, instead of letting that poor creature die.” Bernhard goes to the institution to see the child and wistfully tells a colleague:

- Bernhard.:

-

Now the mother tells me she hoped I’d come one more time to help her child. You know what she meant by “help.” I’m about ready to leave the profession … I also had another case at the time. You know I treated Hanna Heyt? … How can the nurse take that?

- His Colleague.:

-

She’s a woman and loves anything helpless.

Later on, when Bernhard appears as a witness in the trial of Thomas Heyt, who is accused of murdering Hanna, he says, “She asked me once, if she took a turn for the worse, and if her life would no longer be humane, that I help her die … At that time, I didn’t see her request as compatible with my oath…” Soon thereafter Thomas says to him, “You said to me, Bernhard, ‘You murdered her.’” Bernhard responds, “Yes, Thomas, and today I say to you, you’re not a murderer.”

Historian Michael Burleigh has pointed out how skillfully and subtly the plot lines are interwoven so that the equation is inevitably made between the voluntary euthanasia of Hanna, the beautiful pianist and wife of a physician, and the wished-for involuntary euthanasia of the child with severe disabilities (Burleigh 1994, 216). Both suffer the loss of beauty—one who will never have it and one who has lost it. Both suffer the loss of control—one who will never have it and one who is losing it. Both suffer the loss of cognition—one who will never have it and one from whom it is slipping away. The subtle message is that just as Hanna is revolted by her present and prospective condition, so we should feel the same disgust on behalf of the institutionalized “blind…deaf…and demented” child. This shields us, the audience, from believing that the disgust is a matter of our own attitudes. As Hanna deserves a merciful death, so does the child.

Amour, a French film, presents in painful, plodding, and pointed detail the ravages of dementia on a cultured music teacher and her husband. By the time he suffocates her with a pillow, the audience is more than ready to end the movie. In The English Patient, the horribly disfigured appearance of the formerly handsome Almásy, whose face is now burned beyond recognition is, at the very least, disagreeable and unappealing. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the formerly lovable, lively, and entertaining McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) appears lifeless and catatonic with a big, ugly scar from a frontal lobotomy just before the Chief suffocates him with a pillow and bursts through the asylum’s window thereby freeing both of them. The argument in all these films is the same—euthanasia is the solution if one wishes to avoid or escape states that horrify or disgust.

10.3.1.3 Equating Loss of Capability with Loss of Reason for Living

In his Poetics, Aristotle says, “Tragedy is a form of drama exciting the emotions of pity and fear. Its action should be single and complete, presenting a reversal of fortune, involving persons renowned and of superior attainments, and it should be written in poetry embellished with every kind of artistic expression” (Brooklyn College n.d.). Films often present the loss of great talent as an argument for euthanasia, evoking in the audience a sense of tragedy and pity as they appeal for moral acceptance and legalization of PAS and euthanasia. This form of argument is especially appealing to contemporary Western academics, such as Norman Cantor, who fear the loss of their academic talents through a disorder such as Alzheimer’s disease, and argue that the tragic quality of this loss justifies suicide (Cantor 2018).

In Ich klage an, the first hint of Hanna’s future decline is her left hand’s unexpected and inexplicable difficulty in playing the piano at a celebratory dinner party. The tragedy to come is heightened by Hanna’s belief or hope that the cause of her weakness is a pregnancy she has been yearning for. When Bernhard suspects she has a neuromuscular disease, she responds, “Having a baby is not a disease.” Before long, she is bedridden, unable to joyfully dance about as she did before.

Million Dollar Baby describes the tragic life of a poor, adrift, relatively older and stubborn female boxer, Margaret “Maggie” Fitzgerald (Hillary Swank), who finally gets a world championship boxing title match with the aid of her trainer Frankie Dunn (Clint Eastwood). During the fight, an illegal punch drops her head onto her corner’s stool leaving her quadriplegic on a respirator. Ultimately, she asks Frankie to assist her in dying:

- Maggie.:

-

I can’t be like this, Frankie. Not after what I done. I seen the world. People chanted my name. Well, not my name, some damn name you gave me. But they were chanting for me. I was in magazines. You think I ever dreamed that’d happen? I was born at two pounds one-and-a-half ounces. Daddy used to tell me I fought to get into this world, and I’d fight my way out. That’s all I wanna do, Frankie. I just don’t wanna fight you to do it. I got what I needed. I got it all. Don’t let them keep taking it away from me. Don’t let me lie here till I can’t hear those people chanting no more.”

- Frankie.:

-

I can’t. Please. Please, don’t ask me.

- Maggie.:

-

I’m asking.

- Frankie.:

-

I can’t.

Of course, in the end, he can and he does.

In Me Before You (2016), whose box office take was more than $208 million, a wealthy quadriplegic man with supportive parents and a woman who loves him chooses euthanasia in Switzerland because he is not the man he was before his crippling accident. His attitude and behavior can be contrasted with that of a similarly wealthy quadriplegic man in a movie based on a true story, The Intouchables (2011). Incidentally, Me Before You, A Short Stay in Switzerland (2009), and documentaries like The Suicide Tourist (2007) highlight in a favorable way the role of Swiss nonprofit organizations like Exit and Dignitas that promote and provide assisted suicide to patients from around the world.

In Mar adentro, we meet beautiful Julia, a lawyer who suffers from Cadasil syndrome, a hereditary leukodystrophy that will ultimately lead to dementia and serious physical disabilities, a subplot that heightens the melodrama. Julia, who supports quadriplegic Ramón in his legal case for euthanasia, does not tell him about her own illness before this interview:

- Julia.:

-

If we end up going to trial, you’ll be asked why you don't seek an alternative to your handicap. For instance, why do you refuse a wheelchair?

- Ramón.:

-

Accepting a wheelchair would be like accepting the crumbs of what used to be my freedom. Look, think about this: You’re sitting there, right? A little less than five feet away. Well, what’s five feet? An insignificant journey for any human being. Well, those five feet necessary to reach you, let alone to even touch you, is an impossible journey for me. It’s a false hope, a dream. That's why I want to die.

An explicit dialogue about the loss of talent takes place in Whose Life Is It Anyway?. An informal hearing has been convened to respond to a quadriplegic former sculptor’s request to be discharged from the hospital to die. The judge interrogates the protagonist, Ken Harrison (Richard Dreyfus):

- Judge.:

-

You tell me why it is a reasonable choice that you decided to die.

- Harrison.:

-

The most important part of my life was my work, and the most valuable asset I had for that was my imagination. Now it’s just too damn bad that my mind wasn’t paralyzed along with my body because my mind, which had been my most precious possession, has become my enemy and it tortures me. It tortures me with thoughts of what might have been and what might be to come, and I can feel my mind very slowly breaking up.

Harrison also says that he is filled with “an absolute sense of outrage that you, who have no knowledge of me whatsoever, have the power to condemn me to a life of torment because you cannot see the pain.” In the end, the judge rejects the majority medical opinion that Harrison is depressed and rules that Harrison can be discharged or “set free,” saying, “I am satisfied that Mr. Harrison’s a brave and thoughtful man who is in complete possession of his mental faculties…” The judge also neglects the fact that the accident resulting in Harrison’s quadriplegia is relatively recent and that, according to Glen Gabbard, psychoanalyst and author of several books on the depiction of psychiatry and mental illness in films, Harrison “may be in a state of grief that will ultimately lift with the passage of time and adjustment to the illness” (Gabbard 2010, 156).

10.3.1.4 Self-Determination and Rights

Whose Life Is It Anyway? argues, in no uncertain terms, that patient autonomy trumps medical and government resistance to PAS and euthanasia. The autonomy argument runs continuously in the background of all contemporary films promoting euthanasia, but this movie brings it front and center. Moreover, unlike most contemporary euthanasia movies, Whose Life Is It Anyway? explicitly and directly confronts the medical profession’s competence and ethics in the management of patients with chronic but not necessarily terminal illnesses.

Whose Life Is It Anyway? is also unique among contemporary films in that it demands that the state, in the person of the judge conducting an informal trial, respond favorably to the individual’s autonomous request to an assumed right to die.

Ich klage an uses the same plot device—a trial—as Whose Life is It Anyway? to promote State involvement in end-of-life decision-making:

- Juror 1.:

-

But can these decisions on life and death be left to doctors?

- Juror 2.:

-

Of course not. They’d take on the responsibility for it. Commissions must be appointed, proper tribunals made up of doctors….

- Judge.:

-

It’s not that simple. The right to kill shouldn’t be given to a doctor alone. These final medical decisions should be left to the state. We would have to pass laws for such “medical courts.” But as soon as possible.

- Juror 3.:

-

I’m an old soldier, gentlemen. It’s evident to me that our state demands a duty to die if need be. But then it should have to give us the right to die, if necessary.

- Judge.:

-

Sure, Major, but the laws applicable here are still different.

- Juror 3.:

-

Of course we will judge Professor Heyt under current law. That goes without saying. But allow me to say, the law is not here to prevent people from worthy moral acts. If that’s the case, the law must be changed.

In an ironic way, the appeal to the State made in both films undermines the argument from autonomy by making the individual dependent upon the State. In both National Socialist and contemporary Western liberal arguments for the “right to die,” the State must grant and safeguard the purported right to PAS and euthanasia. In the contemporary Western formulation, the State is compelled to do so out of its respect for autonomy. In the Nazi formulation, the State is compelled to do so out of reciprocity given its demand for a duty to die. Both, however, are fundamentally arguments for a right to PAS and euthanasia.

10.3.1.5 Conflation of Voluntary, Involuntary, and Nonvoluntary Euthanasia

Philosophical and legal arguments for PAS and euthanasia always begin by making the case for voluntary death by competent adults. The requirement of a voluntary request is proposed as a “safeguard” to protect against the possibility of ever moving in the direction of involuntary euthanasia as practiced by the Nazis. Yet the arguments based on mercy and disgust as well as norms of equal treatment for all suffering persons push against such a boundary. The initial move is from the first-person voluntary request, “Please help me die,” to the third-person, nonvoluntary judgment, “She would not want to live this way” and seems simple and logical. From here, the move to the generalized, nonvoluntary, “No rational person would want to live this way” is inexorable. The European experience with euthanasia seems to confirm this conflation. Movies often present a central case for the voluntary but foreshadow the argument for the nonvoluntary in their depictions of euthanasia.

As noted above, Ich klage an masterfully intertwines the two plotlines (Burleigh 1994, 216). Hanna’s voluntary request for euthanasia calls forth equivalent mercy from the parents of a neurologically damaged child who has no first-person voice and is unable to make such a voluntary request. It becomes, therefore, the moral duty of the parents to make the third-person request on their child’s behalf. And, as his dialogue at the trial demonstrates, the principled and noble Dr. Lang has changed his mind about refusing requests for both voluntary and nonvoluntary euthanasia, and so should we, the audience.

Several contemporary films portray the nonvoluntary but compassionate killing of cognitively impaired patients and/or loved ones, such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Leisure Seeker (2017), and Monsieur & Madame Adelman (2017). The overriding message is that the judgment, “I would want assisted suicide or euthanasia for myself” can be generalized to decisions made on behalf of others.

10.3.1.6 Casting All Opposition as Out-of-Date Traditionalism

The makers of Ich klage an were unlikely to attack either traditional medicine or religion. German physicians and medical scientists, arguably the best in the world at the time, were held in the highest regard in Germany and around the world. For example, famed surgeon Michael DeBakey studied in Germany during the Third Reich because it had the best doctors and medical researchers (DeBakey 2010, 221). Furthermore, the Nazi government did not want to alienate the medical profession because it was badly needed to implement the Sterilization Law, examine potential marriage partners for genetic fitness, euthanize children and adults, and carry out the Final Solution by making selections on the ramps, supervising the gas chambers, and performing military and other medical research. In addition to the portrayal of Drs. Heyt and Lang as competent, thoughtful, and moral physicians, this exchange between the jurors during a break in Dr. Heyt’s trial demonstrates the filmmakers view of physicians:

- Juror 1.:

-

Professor Heyt should be acquitted precisely because he is a role model for all doctors.

- Juror 2.:

-

What if doctors started relieving suffering? Wouldn’t people say no? Prefer even terrible pain to dying? People would condemn doctors.

- Juror 1.:

-

Come on. Everyone knows what doctors do and continue to do for us. They discovered X-rays and radiation, and became cripples doing it. If someone is terminally ill and would rather die, why should he keep living? If someone asks to die, as the last help who can spare him, doctors should be allowed to help.

Indeed, it would appear, the medical profession was not alienated by its depiction in the film. The Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service, or SD, the Nazi intelligence service), issued a “Report from the Reich” that evaluated the response to Ich klage an. The opening remarks about medicine’s response were: “As regards medical circles, a mostly positive response is reported to the questions raised by the film. Younger doctors in particular, apart from a few bound by religious beliefs, are completely in favour” (Leiser 1974, 147; italics in original).

Similarly, the Nazi government wanted to avoid creating more internal and external enemies by alienating organized religions. Here is the one exchange about religion in Ich klage an, which also occurs during a break in the trial:

- Juror 3.:

-

It is God’s will. He sends suffering so that men will follow his cross and attain eternal bliss.

- Juror 4.:

-

My dear sir, I would like to believe that God is not that cruel, nor the pastor, by the way.

The SD “Report from the Reich” described a much less favorable response to the film from the Church than from medical circles: “The attitude of the Church, both Catholic and Protestant, is one of almost total rejection” (Leiser 1974, 146; italics in original).

Contemporary filmmakers routinely paint opposition to PAS and euthanasia as dependent upon a quaint, irrational clinging to the traditional moral codes of religion and “dead white men” like Hippocrates as opposed to the bold, progressive embrace of seemingly new ideas. Priests and religious institutions are portrayed as unhelpful or useless in several contemporary films, such as The Sea Inside, Million Dollar Baby, and The Barbarian Invasions. In the surprisingly few contemporary movies that either mention or include medical personnel, they are depicted as cold and unfeeling at best, as in Million Dollar Baby or Whose Life Is It Anyway?, or malevolent at worst, as in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest where Nurse Ratched is portrayed as the embodiment of evil. Indeed, just as in Ich klage an, where both the self-sacrificing medical scientist and the principled general practitioner ultimately support euthanasia, nurses in both The English Patient and The Barbarian Invasions also reverse their initial opposition and finally administer lethal doses of medication to Almásy and Rémy, respectively.

In contemporary euthanasia films, any friends, loved ones, or family members who oppose assisted suicide and euthanasia are either given short shrift or, more likely, reverse course and lend support to the patient’s decision, as in The English Patient, Million Dollar Baby, and Mar adentro. Also, little consideration is given to the impact of a completed assisted suicide and euthanasia on loved ones, family members, the medical profession, and society. For example, in Mar adentro, Ramón asks of Julia, rhetorically and laughingly: “Why do people get so shocked when I say that I want to die? As if, as if, as if it were something contagious.” Indeed, studies have shown that PAS and euthanasia are contagious—states that permit PAS and euthanasia have a higher rate of unassisted suicides than states that do not permit PAS (Jones and Paton 2015, 599–604) and euthanasia (Boer 2017).

10.3.1.7 Economics

Nazi ideology and propaganda documentaries were very explicit in arguing for the elimination of the economic burden imposed on the state by caring for the disabled—these costs were a primary justification for euthanasia. Yet, in Ich klage an, the burden is primarily psychological and perhaps physical but not economic. In contemporary cinema, economic motivations are generally associated with the “bad guys.” Therefore, appeals to economic reasons in support of euthanasia are rarely made explicit. In both Mar adentro and Amour there are only brief and vague references to the economic cost of home care for someone with serious disabilities. Be that as it may, economic arguments do seem to play a significant background role in actual end-of-life decision-making (Trachtenberg and Manns 2017, E101–E105; Sulmasy et al. 1998, 974–978).

One contemporary film, however, The Barbarian Invasions, explicitly makes the economic argument. The powerful visual display of hospital overcrowding, the ability of Rémy’s son to get improved care for his father by spreading money around the hospital, and the son’s indifference to the expense of purchasing heroin illegally imply that economics influence end-of-life decision-making in Canada. One can only wonder about the influence of this Oscar-winning 2003 film on the Canadian debate about PAS and euthanasia.

10.3.1.8 Eugenics

As we have noted, one major argument for euthanasia has been its purported eugenic benefit, a major ideological force behind the Nazi euthanasia programs. Eugenicists throughout the Western world argued that Judeo-Christian and Hippocratic commitments to caring for the sick had resulted in many genetically unfit persons surviving and reproducing in ways that violated the natural struggle for life that would have eliminated undesirable traits from the human gene pool. Sterilization and euthanasia were proposed as correctives. Early pro-euthanasia films commissioned by the Nazis took this approach directly, depicting “genetically sick” (erbkranken) patients such as Valentina Z in A 41/2-Year-Old Patient with Microcephaly as subhuman and interspersing disturbing scenes from neuropsychiatric and other chronic care institutions with lectures given by dynamic professors to young, healthy, and enthusiastic students. Such documentary and docudrama films, however, did not make for popular cinema and, while perhaps of use in schools for health care professionals, did not reach the general public.

Overt arguments for euthanasia on the basis of negative eugenics are almost unheard of in the Western world today and are not evident in movies. American eugenicists, however, consciously transformed eugenics into medical genetics (Comfort 2012) and exported eugenic policies to the Third World for decades after World War II (Connelly 2008). Also, a systematic campaign to eliminate Down syndrome through abortion is underway in Iceland (Quinones and Lajka 2017), and others call for “liberal eugenics”—enhancing the human race through genetic engineering (Agar 1998; Buchanan et al. 2000; Persson and Savulescu 2019).

Ich klage an avoids a direct link between eugenics and euthanasia, even though its subplot of the care of the child with meningitis gestures in that direction, and allusions to lab animals and the struggle for life also clear the ground for such arguments. The film was, therefore, a mature development in German cinematic depictions of euthanasia during the Nazi period.

Contemporary films avoid eugenics, but one made-for-television movie adapted from Ira Levin’s play, Dr. Cook’s Garden, tackles the issue head-on. The film tells the story of a genial general practitioner played by a cast-against-type Bing Crosby whose New England town appears to be blessed because the “nice” people live to a ripe old age and the “mean” ones die prematurely. As it turns out, Dr. Cook has been weeding both his garden and his town of “life unworthy of living.” Also, a very beautiful and powerful German Oscar-nominated historical drama, Werk ohne Autor (Never Look Away) (2018), portrays the heartbreaking Aktion T4 euthanasia of a woman who is the beloved schizophrenic aunt of an artist (inspired by Gerhard Richter) who mourns her death when he is a child and then, as an adult, unwittingly falls in love with and marries the daughter of the man who personally ordered his aunt’s death.

10.4 Discussion

As demonstrated above, there are many similarities in the arguments used to promote PAS and euthanasia in Nazi and contemporary feature films. These similarities include enthusiastic deployment of the argument from mercy, the argument from fear and disgust, the depiction of lost talent as the loss of a claim to life, and the suggestion that opposition is out-of-touch traditionalism. Feature films regarding PAS and euthanasia in both eras downplay economic and eugenic arguments, although these arguments sometimes make cameo appearances. The Nazis were a bit more likely to conflate the voluntary with the nonvoluntary, although a few contemporary films depict third party judgments that the patient would have wanted PAS and euthanasia. Films from both eras make appeals for mercifully euthanizing animals, although the Nazis were more likely to color that appeal with the hue of natural selection. Both defend a right to PAS and euthanasia, although, for the contemporary West, this right is derived from autonomy, and for the Nazis, it was owed to the citizen who had a duty to defend the State to the point of death.

The films of both eras were similar and yet dissimilar in their goals. In a general sense, their goals were the same: to promote public acceptance of PAS and euthanasia. In another sense, however, their goals may have been different. Nazi propagandists made Ich klage an to promote societal support for legalization of an ongoing but secret program of medicalized euthanasia for patients whose lives the government declared not worth living. By contrast, contemporary Western filmmakers have made euthanasia films to promote societal and governmental support for legalization and medicalization of PAS and euthanasia for patients who declare their own lives not worth living.

10.4.1 The Medical Profession’s Ethic

This difference in goals may help explain one marked disparity in films from the two eras: the prominence of principled physicians throughout Ich klage an and the almost total absence of physicians in the six Oscar-winning and most other contemporary euthanasia films. This absence is, at first, surprising because existing and proposed legislation in virtually all jurisdictions except Switzerland require physician participation. One possibility for this omission is that including physicians in the storyline would unnecessarily complicate the film. Another possibility is that the filmmakers might actually be promoting physician-free, altruistic assisted suicide as practiced in Switzerland. All efforts to legalize assisted suicide in the US, however, have designated physicians as those charged with administering the practice.

Perhaps the strongest possibility is that contemporary filmmakers concluded they did not need the support of the medical profession at all. Once society favored PAS and euthanasia, the government would legalize it regardless of the medical profession’s objections, if any. Society and government would define the medical ethos.

As we argue below, because the medical profession increasingly has abdicated its moral authority and abandoned its professional responsibilities, the filmmakers may have reasonably concluded that society and the government would have little trouble getting the medical profession to both accept patients’ declarations that their lives were not worth living and to assist with patients’ suicides. The pressure both within and without the medical profession to declare official “neutrality” on the subject of PAS strongly suggests this may be the case (Sulmasy et al. 2018).

While many Western societies and governmental jurisdictions have social policies and legislation that clearly favor PAS and euthanasia, medicine has become, in fact, confused about its position. Focusing single-mindedly and successfully on science, Western medicine continues the Nazi preoccupation with, to use Leon Kass’s term, science as salvation in the utopian quest for a more perfect human. He goes on to explain how, in Western liberal democracies, “A free people, choosing for ourselves, can and very likely will produce similar deadly fruit from the same dangerous seeds, unless we are ever vigilant against the dangers” (Kass 2010, 110).

In regard to PAS and euthanasia, medicine increasingly accepts the belief that medicine is “morally neutral.” Whereas some professional organizations like the World Medical Association (World Medical Association 2019), the American Medical Association (American Medical Association n.d.), and the American College of Physicians (Sulmasy and Mueller 2017) officially oppose PAS and euthanasia, they are under pressure within and without to drop their opposition. When medical organizations opposed to PAS and euthanasia change their positions to “neutral,” as the California Medical Association has done, the results are predictable: PAS is now legal in California (Kheriaty 2019, 23). When professional medical organizations assume a neutral position on PAS and euthanasia, they are abdicating their responsibilities to patients and physicians alike, thereby creating an ethical void eagerly filled by the many nonphysician strangers at the bedside.

By abandoning traditional religious and Hippocratic medical ethics with their commitment to life and healing in favor of secular, philosophical bioethics that includes a commitment to social justice (Abbott 2019), medical educators are further distancing medical students from the ethics of the individual doctor-patient relationship in favor of the population-based, state-volk relationship. If medical schools incorporate additional “social justice” issues into their curricula at the expense of education about healing patients, then they will crowd out basic medical training, or, as Stanley Goldfarb, former associate dean of curriculum at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, bluntly says, “If this country needs more gun control and climate change activists, medical schools are not the right place to produce them” (2019).

This delegation of ethics to others on the part of the medical profession today is not unlike what happened to medical ethics in Germany in the 1930s and 40s. The pioneering German medical profession became the first in the world to require medical ethics education. Rudolf Ramm’s Medical Jurisprudence and Rules of the Medical Profession (Ärztliche Rechts- und Standeskunde) became the standard textbook for the required Nazi medical school medical ethics course (Bruns 2020, 78). In the introduction to the first English translation of Ramm’s textbook, Melvin Cooper writes, “A constitutive feature of a mature profession is that it is ‘self-regulating,’ that is, that it has an internally generated and adjudicated code of behavior” (2019, xviii). Similarly, “A profession is an occupation which has assumed a dominant position in a division of labor, so it gains control over the determination of the substance of its own work. Unlike most occupations, it becomes autonomous or self-regulating” (2019, xxii). German physicians ceded control of their ethics to Nazi ideology, and enthusiastically embraced it. What Ich klage an shows is the awakening of both practicing and academic physicians to that ideology in the persons of Bernhard and Thomas, respectively.

10.4.2 Lives Not Worthy to Be Lived