Abstract

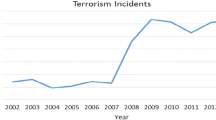

This chapter catalogs the economic cost to an economy from two major terror attacks (9/11 and Madrid Train Attacks, 2004), the country-wise and global cost of terrorism following the Institute of Economics and Peace’s methodology and the direct costs of US involvement in Syria and Afghanistan. It also contains a back-of-the envelope economic cost–benefit analysis of counter-terrorism measures.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Sometimes it is not easy to draw a line between direct and indirect costs of terrorism. For instance, should we consider increased security costs as direct or indirect?

- 2.

Between 50–60% of this figure is attributed to the loss of World Trade Center buildings ($3 to $4.5 billion) and office equipment and software ($3.2 billion). See the authors’ Table 2.

- 3.

See (Enders & Sandler, 2012, Chapter 10).

- 4.

At the time of their writing, Navaro and Spencer (2001) did not have a precise estimate of fatalities. They assumed that it was $6000, and hence the total value of lives lost was placed at $40 billion.

- 5.

This is less than the estimate obtained by Becker and Murphy (2001).

- 6.

The insurance-value losses of World Trade Center and Pentagon buildings were $22.7 billion. See Enders and Sandler (2012, Chapter 10).

- 7.

Following the 9/11 attacks, reduction in coverage for damage due to terror attacks was feared to cause lending problems. As a result, the USA passed the Terrorism Insurance Act in 2002, which created a temporary federal program. The Act provided a risk-sharing mechanism between the Federal government and to the insurance industry to share losses in the event of major terror attacks on business infrastructures. It has been periodically extended ever since. The latest is the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2015, which places the end of 2020 as the expiration date of this insurance program.

- 8.

This conversion is based on consumer price index being 11.58% higher in 2011 than in 2006, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- 9.

Another estimate due to Riedel (2011) places the cost of property damage in New York and Washington alone at about 100 billion and cumulative economic cost to the global economy at 2 trillion, both in 2011 dollars.

- 10.

The cost of one death is $8,888,692 and that of one injury is $120,622, both at 2008 dollars for the USA. These are a bit different from the numbers in McCollister et al. (2010), as they are adjusted for terrorism-related death and injury, as opposed to other forms of violence.

- 11.

PPP per-capita GDP is based on PPP -adjusted exchange rate. Purchasing power parity compares the cost of a common representative basket of goods across a pair of countries. If, say, in the USA it is $100 and in Japan it costs ¥8000, then the PPP -adjusted exchange is \(\$1=\yen 80.\) (The costs of the representative basket of goods may be imputed from the respective consumer price index.) This is the different from the nominal exchange rate between two currencies that is based on daily trade in the world currency market and thus can vary daily. There are some common factors affecting the two exchange rates, but there are different factors as well.

- 12.

GTD categorizes terror events into four types: minor, major, catastrophic, and unknown. For the unknown category, property damages are assumed to be zero. For events with available reported costs of property damage, the figures are converted to the US dollars. Those associated property damage costs less than $1 million, between $1 million and $1 billion and higher than $1 billion are defined as minor, major, and catastrophic, respectively. The GTD dataset also contains information on the tactics used in terror events like bombing/explosion, armed assault, hijacking etc., and, the cost of property damage from some, not all, terror events during a year. From this information, IEP calculates, for each country, the average cost of property damage for each tactic and for each of the three aforementioned categories (minor, major, and catastrophic). These averages are applied for all terror events in terms of tactic whether or not property damage estimates associated with them are available, and, then summed over all events. Next, they are scaled on the basis of the income type of the country: high-income OECD, high-income non-OECD, upper middle income, and lower income country groups (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2016b).

- 13.

- 14.

In the same year, the European Counter-Terrorism Centre was created within Europol.

- 15.

SOCOM stands for Special Operations Command .

- 16.

The number for the fiscal year 2022 is amount requested by the Biden administration.

- 17.

Stimson’s estimate of CT -related US spending from 2002–2017 does not include foreign contributions to counter-terrorism ; state and local investments in counter-terrorism ; some dual-use programs and spending, such as drones; economic losses and secondary effects associated with the long-term cost of counter-terrorism operations and homeland security; and classified CT spending.

- 18.

No numbers are shown for other foreign aid as these are too small compared to the other three categories.

- 19.

Discretionary spending is spending that is subject to the appropriations process, whereby Congress sets a new funding level each fiscal year (which begins October 1st) for programs covered in an appropriations bill. As opposed to discretionary spending, there is mandatory spending, which does not take place through appropriations legislations. It includes entitlement programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, and required interest spending on the federal debt. Mandatory spending accounts for about two-thirds of all federal spending. In most cases, but not all, mandatory spending is ongoing; it occurs each year absent a change in an underlying law that provides the funding.

- 20.

In contrast, for interpersonal violence in general, the expenditure is considerably less than the economic losses.

- 21.

This includes security spending by the Department of the Homeland Security, the Department of Defense, the Department of Justice, the Department of Energy, the Department of Health and Human Services and 26 other federal agencies, while it does not include the cost of war in Afghanistan and Iraq or CT -related assistance to foreign governments. Additionally, it includes indirect opportunity costs.

References

Becker, G. S., & Murphy, K. M. (2001). Prosperity Will Rise Out of the Ashes. Wall Street Journal, October 29.

Blalock, G.., Kadiyali, V., & Simon, D. H. (2009). Driving fatalities after 9/11: A hidden cost of terrorism. Applied Economics, 41(14), 1717–1729.

Buesa, M., Valiño, A., Heijs, J., Baumert, T., & Goméz, J. G. (2007). The Economic Cost of March 11: Measuring Direct Economic Cost of the Terrorist Attack on March 11, 2004 in Madrid. Terrorism and Political Violence, 19(4), 489–509.

Carter, S., & Cox, A. (2011). One 9/11 Tally: $3.3 Trillion. NYTimes.com, Interactive, (New York Times), September 8, accessed on September 2, 2019.

Clarke, C. P. (2015). Terrorism, Inc.: The Financing of Terrorism, Insurgency, and Irregular Warfare. Praeger.

Crawford, N. C. (2021). The U.S. Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars. Paper, Watson Institute, Brown University.

Crawford, N. C., & Lutz, C. (2021). Human and Budgetary Cost to Date of the U.S. War in Afghanistan. Paper, Watson Institute, Brown University, April 15.

Enders, W., & Sandler, T. (2012). The political economy of terrorism (2nd edn.). Cambridge University Press.

European Parliament. (2016). Counter-Terrorism Funding in the EU Budget. Briefing, April.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2014a). The Economic Cost of Violence Containment.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2014b). Global Terrorism Index 2014: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2015). Global Terrorism Index 2015: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2016a). The Economic Value of Peace 2016: Measuring the Global Economic Impact of Violence and Conflict.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2016b). Global Terrorism Index 2016: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2017). Global Terrorism Index 2017: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2018). Global Terrorism Index 2018: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports, Sydney, November.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2019). Global Terrorism Index 2019: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports, Sydney, November.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2020a). Global Peace Index 2020: Measuring Peace in a Complex World. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports, Sydney, November.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2020b). Global Terrorism Index 2020: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports, Sydney, November.

Kunreuther, H., Michel-Kerjan, E., & Porter, B. (2003). Assessing, Managing and Financing Extreme Events: Dealing with Terrorism. NBER Working Paper No. 10179.

McCollister, K. E., French, M. T., & Fang, H. (2010). The cost of crime to society: New crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 108(1), 98–109.

Mueller, J., & Stewart, M. G. (2011). Terror, security and money: Balancing the risks, benefits and costs of homeland security. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mueller, J., & Stewart, M. G. (2014). Evaluating counterterrorism spending. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 237–247.

Navaro, P., & Spencer, A. (2001). September 11, 2001: Assessing the Cost of Terrorism. Milken Institute Review, Fourth Quarter, 16–31.

Riedel, B. (2011). The World After 9/11—Part I. Yale Global Online, Setember 6, https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/world-after-911-part-i, accesses on August 31, 2019.

Rose, A. Z., Oladosu, G., Lee, B., & Asay, G. B. (2009). The Economic Impacts of the September 11 Terrorist Attacks: A Computable General Equilibrium Analysis. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 15(2).

Stimson Study Group. (2018). Counterterrorism Spending: Protecting America While Promoting Efficiencies and Accountability. Report by Stimson Center.

van Ballegooij, W., & Bakowski, P. (2018). The Fight Against Terrorism: Cost of Non-Europe Report. RAND-Europe for the European Parliamentary Research Service, European Parliament.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Das, S.P. (2022). Economic Costs of Terrorism and Costs of Counter-Terrorism Measures. In: Economics of Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism Measures. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96577-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96577-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-96576-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-96577-8

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)