Abstract

The few existing studies on Denmark showed that political scientists are not well represented in public committees, while subsequent studies argued that the means by which political scientists offer their advice are writing articles in the media and participation in other such means of communications. The survey used in this study provides empirical data offering interesting new evidence regarding the role of political scientists in the policy advisory system in Denmark. It points to the fact that political scientists deliver substantial policy advice via informal contacts and forms of communication, e.g. to civil servants, civil society organizations, politicians and advisory bodies, mainly at the national level. According to the survey’s respondents, this advice is based on sound scientific evidence, which fits well with survey evidence emphasizing the belief that experts are more prominent than opinionating scholars in Denmark compared to other countries. Thus it would seem that political scientists’ role as providers of informal and direct policy advice has been underestimated. In the light of the amount, and the soundness, of the advice provided informally, Denmark may not be a case of restrained wisdom after all.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The role and importance of policy advisors in Denmark is a research topic that has received very little attention. This is particularly true of research based on a ‘policy advisory systems’ approach (Craft & Howlett, 2013; Hustedt & Veit, 2017); Little research into the Danish political system has been conducted using such a theoretical approach. Previous studies within the Danish context have mainly focused on the role of interest organizations (Christiansen & Nørgaard, 2003; Christiansen et al., 2010) or of civil servants (Bo Schmidt-Udvalget, 2015; Grønnegaard Christensen & Mortensen, 2016; Schmidt & Christensen, 2016). Recently, there has been increasing interest in the role of think tanks in Denmark (Kelstrup, 2016, 2017), and also in the concept and phenomenon of ’policy professionals’. Policy professionals systematically strive to have an impact on public policy, but they are not classified as politicians, civil servants, lobbyists or policy entrepreneurs (Poulsen & Aagaard, 2020; Kelstrup, 2020). Gravengaard and Rendtorff (2020) present an overview of the different roles played by scientists in the dissemination of research findings beyond the academic environment.

While the international literature on policy advisory systems (e.g. Craft & Howlett, 2013; Craft & Halligan, 2017) points to externalization and politicization as important trends, the empirical basis is mainly taken from the systems witnessed in the English-speaking world. Intuitively, it seems difficult to apply such conclusions directly to a Scandinavian politico-administrative context (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011). The reason for this is that a classical Scandinavian, consensual neo-corporatist country like Denmark is characterized by close relationships between policymakers and interest organizations within the context of a classical unitary, centralized state (see also the chapter on Norway in this volume). Furthermore, there is very little information available regarding the involvement of Danish political scientists in policy-advisory activities.

The survey data collected for this book project, together with a number of other data sources, mean that there is now more systematic empirical information available which may indicate the state of the art and trends of Denmark’s policy advisory system and the role of its political scientists in that system. Some of these trends correspond to assumptions about the relationship between (academic) experts and policymakers. Other trends seem to contradict what have been broadly accepted assumptions, including those present in the academic literature, on the relationship between political science expertise and policymakers in Denmark.

This chapter is set out as follows. Firstly, the policy advisory system in Denmark is described and classified in terms of its general and comparative characteristics, and the country’s political scientists are placed within that system. With regard to the ‘location model’ presented in Chap. 2 of this book, the main access points for political scientists are established and specified for Denmark. Secondly, survey data are used to describe the advisory roles of political scientists in Denmark vis-à-vis the general typology of advisory roles and a comparative perspective is offered based on the overall dataset and the other country chapters contained in this book. Thirdly, the normative conceptions of political scientists regarding policy advisory behaviour vis-à-vis incentives and career opportunities and constraints, are discussed. The chapter closes with some concluding remarks and possible avenues for further research.

2 Existing Images of the Advisory Role of Political Scientists in Denmark

2.1 The Danish Policy Advisory System

Traditionally, Denmark has been classified as an example of a neo-corporatist political system (Armingeon, 2002) with a significant tendency towards the employment of a Scandinavian politico-administrative system (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011), situated within a universalist welfare state (Esping-Andersen, 1990). Its corporatist characteristics have been particularly evident in policy sectors such as the labour market and business regulation, as well as in some areas of public service production (Christiansen & Nørgaard, 2003; Christiansen et al., 2010). Private interest government (Streeck & Schmitter, 1985) is therefore also a clear feature of the Danish political system.

As opposed to the neighbouring Sweden, a country with a corporatist tradition, that shares many of the aforementioned features with Denmark, policy decisions in Denmark seem more based on pragmatically developed processes than on systematic, evidence-based decision-making procedures. This has implications when classifying and specifying the policy advisory system in Denmark. The nationalPower and Democracy Research Project (Togeby et al., 2003; see also Albæk et al., 2003) analysing the state of Danish democracy over the period from 1998 to 2003 drew the following clear conclusions:

In Denmark, there has never been a strong tradition of relying on available knowledge and scientific evidence when making political decisions—as opposed to Sweden for example. The scientific/analytical level of Danish public commission reports has often been of a low quality. Public commission reports have appeared as the result of negotiated, rather than analytical, approaches to political problems. Much evidence shows that the knowledge-based foundation of political decisions has declined even further over the last couple of years. Increasingly fewer legislative proposals have been prepared by public commissions, and even when this has been the case, the lack of time available has been much more constraining than earlier (…). It seems to be that in general decision-makers have got used to just ‘giving it a try’, and then changing their decisions later when results and consequences are unforeseen and/or less fortunate’ (Togeby et al., 2003: 382 (author’s translation)).

In 2017-2018, researchers reviewed the findings of the original Power and Democracy Research Project, and evaluated whether the conclusions of that project were still valid after more than a decade of further research into political and societal change in Denmark had been conducted (see Økonomi & Politik, 2018). They concluded that it is still very rare for political decision-makers to use systematic knowledge and scientific evidence, while there is now a tendency for political decision-making processes to take even more distance from scientific knowledge (Christiansen 2018a). Based on survey data regarding political scientists’ views on how they, as experts, are being used as policy advisors, the question of the advisory roles of political scientists in Denmark will now be assessed from the international and comparative perspectives.

2.2 Political scientists vis-à-vis other scientists as policy advisors

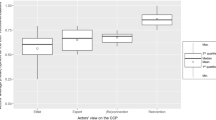

As previously mentioned, there are limited data regarding the role of political scientists as policy advisors in the Danish policy advisory system. Across a fragmented field, there are however a few studies that can offer an overview of the situation. In an unpublished paper, Christiansen (2018b) investigates what changes and developments have taken place in the role of Danish publiccommittees during the period from 1972 to 2017. The research question of Christiansen’s study is whether any significant changes have been seen regarding the role ofpublic committees in the Danish political system and in Denmark’s political decision-making. Given that the focus of this chapter is on the policy advisory roles of political scientists in Denmark, it is particularly interesting to see that Christiansen’s paper comprises an analysis of the distribution of the professions of members of public committees. Figure 6.1 below shows the results of that analysis.

Proportion of judges, other jurists, economists and political scientists in public committees relative to other committee members, 1972-2017,—Denmark. Source: Christiansen (2018b)

It appears that the experts sitting on Danish public committeeshave not been evenly distributed in terms of their different professions. The Majority of such committee members have been legal experts such as judges and professors of law. These two groups have been almost equally represented and 910 out of a total of 1685 (i.e. 54%) expert members have had a legal background. Both of these groups of individuals with legal training have increased their respective shares of seats on said committees over the course of the 45 years under examination. Political scientists, on the other hand, have played a modest role as committee members: totalling 66 committee members all told, they have only accounted for 4% of all the experts concerned. According to Christiansen (2018b), the most surprising fact with regard to committee membership has been the absence of economists (and to a certain degree of political scientists as well).

Another study of scientific advisory services is Kelstrup’s (2020) analysis of the educational and professional backgrounds of ‘policy professionals’ in Danish think tanks. His study offers a nuanced take on Christiansen’s analysis of public committees, as Kelstrup finds a correlation between the employment of members of a certain professional category on the one hand, and publicity in the Danish parliament (Folketinget), and in national newspapers on the other. Advocacythink tanks appear particularly keen on employing the services of economists, while employees with a training in economics are correlated positively with references and publicity, both in the Danish parliament and in the country’s national newspapers (Kelstrup, 2020: 71). Of more than a hundred policy professionals working for 10 different Danish think tanks, some 40% were trained as economists, compared to 20% who were trained as political scientists.

A third important work is that of Albæk et al. (2011), who conducted surveys in 1998 and 2007 of the types of expert referred to in Danish newspapers’ election coverage, the topics that the experts commented on (e.g. substance or process), and changes over time. What they discovered was that researchers are clearly the most frequently used experts in election campaign articles. The vast majority (94%) of such researchers are from the social sciences. Of the social science experts appearing in election campaign articles published in Danish newspapers, almost two-thirds were political scientists while 20% were economists (Albæk et al., 2011: 54). This finding may not be particularly surprising given that political scientists are by definition experts on matters of politics, including elections and political parties.

Thus, a major—and directly measurable—formal access point for Danish political scientists as policy advisors is that of public committees, where, however, political scientists are not a prominent presence. Nor are they prominent in the Danish think tanks compared to economists. Political scientists are, however, much more visible in public media; for example, they often feature in newspaper articles on topics such as political-administrative processes and politicalinstitutions. The picture depicted thus far may lead one to believe that the emergence of political scientists as experts and policy advisors seems to happen mostly via informal access points, such as public media, where they may advise and offer their opinions on elections, political parties, and the related processes of the political system. While this may be the impression given by the existing empirical data, the next step we shall take in this chapter is to examine the views and activities of political scientists more extensively.

3 Surveying Advisory Activities of Political Scientists

The analysis presented in this section builds on data generated by a large-scale cross-national survey (see Chapters. 2 and 3 of this volume for details). A total of 61 of the 297 Danish political scientists invited to participate in the survey actually responded (a response rate of 20.5%). All those scholars responding to the survey were identified as political scientists employed at one of Denmark’s universities or scientific research institutions.

Some 80% of the respondents are employed on a permanent contract (tenured professorships or associate professorships), while the remaining 20% are employed on a non-permanent basis (e.g. assistant professorships). Three-quarters are male, 21% are female, while a few chose not to disclose their gender. Altogether, the sample can be considered representative of political scientists employed at Danish universities or scientific research institutions at post doctorate level or higher. Over 90% of the Danish respondents hold a PhD degree or equivalent qualification.

The survey questions reported below cover different types of advisory activity, recipients of advice, channels, levels of government, topics of advice, and the viewpoints of political scientists that may encourage or discourage them from engagement in such activity. In this way, we may also be able to contribute to the discussion on how ‘relevant’ Danish political scientists are to policymakers and to society at large.

3.1 Activities and Role Types

Applying the locational model presented in Chap. 2 and importing the survey data for Denmark, informal access indeed seems to be at least as important as formal access when political scientists choose, or they are called upon, to deliver policy advice. While approximately one out of three Danish political scientists claims that he or she engages with politicians when delivering policy advice, engagement with political parties is less frequently observed, with only one out of five doing so. On the other hand, two-thirds of all respondents engage with civil servants. With regard to advisory bodies, think tanks, interest groups, and other civil society organizations and citizen groups, some 35% of respondents engage with these policy actors; while only 25% engage with international organizations. For the distribution of policy advice among recipients, see Table 6.1.

With regard to the level of governance at which political scientists engage, some 25% of them engage at the sub-national level, while 17% engage with EU or transnational and international organizations. Their primary focus is the national level: over two-thirds of political scientists are oriented towards the central institutions of government, thus emphasizing the importance of national political and administrative institutions as recipients of advice.

In other words, according to the survey data, the main access point for Danish political scientists consists of a direct link between the internal government arena and the external academic arena, with the latter providing advice both formally and informally. Civil servants operating in ministries and national public authorities appear to be the most important points of contact for academic political scientists in Denmark.

On what topics do political scientists usually provide their advisory knowledge? It appears that topics are distributed somewhat unevenly, with advice on social welfare (20%) and international affairs, respectively to government and public administration organizations, representing the top two areas of advice, with almost 30% of the population of political scientists giving advice in each of these areas. With regards to the sub-disciplinary focus of the political scientists concerned, political science in general is the leading one (56%), but it is followed closely by public administration (39%), public policy (36%), and social policy and welfare (18%).

Applying the typology of advisory roles, six out of ten political scientists can be classified as experts, indicating that they provide policy advice based on scientific knowledge. Some three out of ten are opinionatingscholars, meaning that they combine the provision of scientific evidence-based knowledge with interpretation and normative statements or with advocacy about an issue. Table 6.2 shows that the ‘pureacademic’ (11.5%) and the ‘publicintellectual’ (1.6%) are roles that few political scientists in Denmark appear to perform.

Compared to the overall sample of political scientists from all countries in the ProSEPS project, political scientists in Denmark tend more to come into the expert category and far less into that of the opinionating scholar. There are also fewer pureacademics among them, and while the presence of the public intellectual is very limited in general, this is even a smaller group in Denmark. Danish political scientists actively deliver scientifically proven expertise to policymakers. They also give their own opinions, albeit less so than in many other countries in Europe.

Looking more specifically at the frequency and content of the policy advice provided, Table 6.3 gives an overview of our combined findings. Almost two-thirds of Danish political scientists state that they only provide advice once a year or less, while 20% say they never provide data and facts about policies or political phenomena. Even fewer analyse and explain the courses and consequences of policy problems. More than 40% indicate that they deliver such policy problem-oriented advice less than once a year or never do so. Danish political scientists are active in providing advice, but they do so by delivering data and facts rather than any comprehensive analysis of the issues at stake.

On the question of whether they offer any assessment of existing policies, institutional arrangements and so on, 3 out of 10 say they never do, while 1 in 2 indicate a frequency of once a year or less often. More than 3 out of 10 never offer consultancy services and advice, or make recommendations on policy alternatives, while almost half of the population of political scientists do so at least once a year or less frequently. Only around 10% of Danish political scientists make forecasts and/or carry out polls at least once a year: this may be accounted for by the fact that the provision of such advice is generally outsourced to professional consultancies specializing in producing forecastsand polls. Thus, the relative prominence of experts comes mostly with factual information provision. Danish experts are less active in the more extensive analysis of problems, polls, or evaluations of existing policy solutions.

Approximately 2 out of 3 political scientists claim that they never make valuejudgements or offer normative arguments. So, 1 out of 3 does in fact engage in normative dialogue with policy actors. This is the main indicator that nearly one-third of political scientists are classified as opinionating scholars (see Table 6.2 on the proportions of ideal-type policy-advisory roles). Yet, this is far less than the average for all European countries.

Another dimension is that of formal and informal advice provision: 20% classify their engagement in the provision of formal policy advice, while 23% say they are mostly informally connected to policymakers. A combination of formal and informal advice is the most frequently adopted approach, with half of the sample of political scientists indicating this. Table 6.4 shows the distribution of the degrees of formality of the advice provided by political scientists. Account should be taken here of the fact that Danish society is characterized by a substantial amount of social capital and considerable trust in the country’s public authorities. Consequently, some of the advice may have been considered by respondents as ‘informal advice’, while in a different political and social culture it may have been considered as constituting more ‘formal advice’. It does, however, remain unclear whether advice provided via informal channels such as workshops, face-to-face communication or public media, is being classified as mainly formal or informal advice. The nature of the advice may thus be classified as somewhat formal by the political scientist even when the communication channel employed is informal.

Political scientists in Denmark employ several different channels in their quest for the dissemination of expertise to policymakers and decision-makers. Over the past three years, half of Denmark’s political scientists used publications (books and articles) as a channel through which to provide policy advice and/or consulting services; and they did this at least once a year, or more frequently. Table 6.5 presents the corresponding findings. Almost the same proportion of political scientists used traditional media channels with an almost identical frequency, while one third disseminated policy advice via policy reports, briefs or memos. Almost half of the political scientists have never written blog pieces or entries in socialmedia, while just over half of them have provided policy advice or professional services in the form of training courses for policy actors, administrative organizations and other actors and stakeholders.

Almost 80% of the political scientists have taken part in public debates over the past three years. Approximately 1 in 2 has appeared on TV, while a slightly smaller percentage has been interviewed on the radio (both groups mainly at national level). Almost 70% have contributed pieces to newspapers/magazines, while only 1 in 3 has contributed to other online media. Some 4 out of 10 political scientists have been on TV, a little more than half have appeared on the radio, and 2 out of 3 have written for newspapers, at least once a year every year for the last three years. Once again, this involvement has mainly been at national level. 1 in 6 state that they have participated in public debate via Twitter, and a slightly smaller percentage via Facebook.

Some 80% of political scientists have used workshops or conferences or face-to-face gatherings with actors and organizations in order to provide policy advice or consultancy. A smaller proportion, some 60%, usually communicate with target actors by phone, e-mail or post.

Comparatively speaking, Danish political scientists are quite active at international conferences, with some 92% of the responding scholars declaring their participation in at least one international conference per year. Such behaviour reflects what most Danish political scientists believe, namely that evidence-based grounds are required for the provision of policy advice (see below); it also fits in with the observation that there are far more experts and less opinionating scholars among the political scientists in Denmark compared to the average distribution of the four types of advisory roles in Europe.

This observation, however, does not fit completely with the initial hypothesis, based on former studies, according to which the main channel of advice for political scientists is not via formal access points (e.g. public committees), but rather through the writing of articles in the public media and the like. According to the respondents, the narrative of political scientists being primarily policy advisors via the public media is not exactly true: much policy advice is apparently provided through informal connections and through its direct disclosure to civil servants, civil society organizations, politicians and advisory bodies; at the same time, it is basically considered valid to do on the basis of scientific evidence only. Hence the main finding is that experts prevail over opinionating scholars in Denmark.

4 Normative Conceptions of Advisory Roles

With regard to normative conceptions of their advisory roles, almost two-thirds of the Danish respondents agree that political scientists should become involved in policymaking, while one-third of them disagree. The vast majority (90%) think that political scientists have a professional obligation to engage in public debate, and strongly disagree with the idea that political scientists should refrain from direct engagement with policy-making actors.

More than two-thirds agree that political scientists should provide evidence-based knowledge and expertise outside academia, but not be directly involved themselves in policymaking. From a comparative perspective, this closely corresponds to the high proportion of ideal type experts among Danish political scientists, and the low proportion of pureacademics. Political scientists in Denmark are thus rather enthusiastic about their knowledge being used by policy actors, and about the idea of political scientists as the producers and conveyors of knowledge for the benefit of the policymakers.

As regards the motivation for engaging in advisory or consulting activities, between one half and two-thirds indicate their intrinsic desire to remain active minded, or see it as part of their academic obligations. However, only one-third think that advisory or consulting activities are important for the advancement of their academic careers. They see their contribution to society as being much more important. Danish political scientists are thus rather intrinsically motivated in their quest to provide advice to policy makers; while they also refer to their professional duty, this is considered to be less significant for the purposes of the advancement of their academic careers.

With regard to perceptions of the visibility of political science research in public debate, more than 9 out of 10 respondents indicate that the research produced by political scientists in Denmark is fairly or highly, visible in public debate. Approximately 6 out of 10 believe that political scientists have a considerable impact on the general public, while the rest state that political scientists have little impact on the general public. Hence, in comparative terms, Danish political scientists consider that they have high visibility in the public media, yet comparatively limited impact on policymaking.

What about normative conceptions of participation in public debate? An incredible 97% find that political scientists should engage in public debate (at least to some extent) as part of their role as social scientists, while only 18% find that engagement in public debate also helps in expanding career options (see Table 6.6).

In response to the question of whether political scientists receive recognition, in terms of career advancement, for their participation in public debate, the answers are rather unclearly distributed: approximately two-fifths believe they do not receive such recognition, another two-fifths are somewhere in between, and one fifth find that political scientists do receive recognition in terms of career advancement as a result of participation in public debate.

About 50% of Danish political scientists tend to agree that they should not engage in public debate until their ideas have been tested in an academic setting, while the other half tend to disagree with such a requirement. Even though only one out of three are opinionating scholars who occasionally offer value-judgements and normative arguments when delivering policy advice, approximately 50% agree that the approval of any expert advice provided through publication in scientific outlets, does not constitute a prerequisite for participation in public debate.

To sum up: political scientists should engage in public debate since this is part of their undertaking, despite the fact that it does not necessarily advance their careers. While they agree that policy advice in general should build on sound scientific evidence, political scientists differ as to whether participation in public debate hinges upon the prior approval of ideas via their publication in academic outlets.

5 Conclusion

The survey data used in this chapter have extended the empirical picture of the involvement of Danish political scientists advising and public debate. While certain previous studies have shown that political scientists are not well represented in public committees and other studies have claimed that the main channel for the provision of advice by political scientists may be writing articles in the media, the survey findings show that political scientists deliver substantial policy advice through informal contacts and channels of communication, directly to civil servants, civil society organizations, politicians and advisory bodies. They do this mainly at the national level, while taking an international approach to the production of their knowledge itself. Internationally peer-reviewed scientific evidence is considered a key prerequisite for advising or opinionating, but not necessarily for participation in public debate more generally.

Based on the aforementioned typology of their advisory roles, 6 out of 10 political scientists in Denmark are categorized as ‘experts’, while 3 out of 10 are opinionating scholars. The rest are either ‘pure academics’ or ‘publicintellectuals’. Hence, compared to other countries and to the overall sample, political scientists in Denmark more often fall into the ‘expert’ category than the opinionatingscholar category. There are also fewer ‘pure academics’ in Denmark than in the overall sample, which may indicate that Danish political scientists prefer to deliver sound, science- based expertise and advice to policymakers; and also that they display a much less common preference for combining policy advice with value-judgements and normative arguments.

The main means by which Danish political scientists provide policy advice appears to be the link with the governmental arena. Furthermore, Danish political scientists report that their advisory activities vary between formal and informal channels of access. Policy advice is mainly centred on political scientists in their academic setting and civil servants operating in ministries and national public authorities. Much of this interaction involving political scientists is informal, and takes place less frequently in formal settings such as public committees. Moreover, Danish political scientists employ several channels by which to provide advice, in their quest for the dissemination of expertise to policymakers and decision-makers, although traditional academic outlets such as books and articles are among the most commonly used. Media articles and courses for practitioners are further such outlets.

Political scientists in Denmark are keen on their knowledge being used by policy actors to enhance evidence-based decision-making in the country. There is considerable belief in the scholarly community’s visibility in public media. The vast majority of political scientists also agree with the statement that they have a professional obligation to engage in public debate. A smaller majority—but a majority nevertheless—believe that their knowledge also has a real impact on political processes. However, as far as career advancement is concerned, most academics do not believe that policy advisory activities help them very much. Only 18% of them find that engagement in public debate helps the advancement of their careers. The most important motivational factor is a sense of professional duty.

As shown, the initial hypothesis based on former studies indicating that the main channel of advice for political scientists is not via formal channels and access points, but rather through the writing of articles in the public media and other similar activities, has been slightly amended with the addition of a further aspect: according to the political scientists themselves, much policy advice is provided via direct contact and communication, through both formal and informal channels, with civil servants, civil society organizations, politicians and national advisory bodies, and is mostly based on sound scientific evidence. However, compared to trained lawyers (present on public committees) and trained economists (much present in think tanks), political scientists in Denmark do not seem to have obtained an equally and publicly recognized role (and one that is directly measurable) as policy advisors in Denmark. Probably because the provision of policy advice from political scientists—which is recognized as an important obligation by the profession itself and is practiced accordingly—is still largely of an informal nature, channelled via public media and direct contacts, and therefore much more difficult to measure and compare, and thus to prove.

Retrospectively, it may not be that surprising to find that political scientists do not very often participate in public committees, given that their main expertise consists in their knowledge of political-administrative processes and institutions, rather than substantive policy issues (e.g. Albæk, 2004). Moreover, most public committees are, as a matter of fact, tasked by the government with addressing specific legal and policy challenges, and less so with challenges regarding political-administrative processes and institutions. There are, however, some prominent exceptions to this general rule. For example, there is a public committee investigating the relationship between civil servants and politicians, which in fact comprised political scientists (Betænkning 1443, 2004). The same goes for the committee tasked with analysing the prospects of political-administrative reform prior to the local government reform in 2005 (Strukturkommissionen, 2004; Christiansen & Klitgaard, 2008). There is also the recent public committee tasked with delivering a retrospective assessment of the decision-making processes leading to the Danish government’s lock-down of the country in March 2020 due to COVID-19, which was also led by a political scientist (Folketinget, 2020; 2021). A recent illustration of the rather limited role of political scientists in national committees is how the policy challenges associated with the COVID-19 crisis resulted in mainly trained economists being considered for advisory roles (see Ministry of Finance, 2020).

Be this as it may, an underestimated point in the literature thus far is that political scientists deliver considerable policy advice via direct contacts and communication with civil servants, civil society organizations, politicians, and national advisory bodies, while they also address questions posed through the media concerning matters relating to political representation and the functioning of policy-making institutions. In the light of this, the following question remains to be investigated further by future research: whether Danish society possesses an insufficient capacity to make practical use of important, well-documented political science knowledge, as a result of the relatively limited presence of political scientists in formal advisory bodies, thus representing a case of ‘restrained wisdom’; or whether the policy advice provided by political scientists via direct contact with decision-makers and stakeholders, and their participation in socialmedia and other informal channels, is actually sufficient to establish a solid knowledge-based foundation for policymaking and society as such. The survey data analysed in this chapter, and the comparative perspective from which the findings can be viewed, may inform such further work on the advisory roles of a scholarly community that is well embedded in the international academic environment, and may have the potential to achieve an even more important policy advisory role within the national political system and society as a whole.

References

Albæk, E. (2004). Eksperter kan være gode nok, men…—Om fagkundskabens politiske vilkår i dansk demokrati. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Albæk, E., Christiansen, P. M., & Togeby, L. (2003). Experts in the Mass Media: Researchers as Sources in Danish Daily Newspapers, 1961-2001. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 80(4), 937–948.

Albæk, E., Elmelund-Præstekær, C., Hopmann, D. N., & Klemmensen, R. (2011). Experts in Election News Coverage. Process or Substance? Nordicom Review, 32(1), 45–58.

Armingeon, K. (2002). Interest intermediation: The Cases of Consociational Democracy and Corporatism. In H. Keman (Ed.), Comparative Democratic Politics: A Guide to Contemporary Theory and Research. Sage Publications.

Betænkning 1443. (2004). Embedsmænds rådgivning og bistand. Betænkning fra Udvalget om rådgivning og bistand til regeringen og dens ministre. Finansministeriet.

Bo Schmidt-udvalget. (2015). Embedsmanden i det moderne folkestyre. Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forlag.

Christiansen, P. M. (2018a). Mørket sænker sig: Magten over de politiske og administrative beslutningsprocesser. Økonomi & Politik, 91. Årgang(1), 95–105.

Christiansen, Peter Munk. (2018b). Balancing Bureaucrats, Interests Groups, and Experts: Danish public committees 1972-2017. Unpublished paper. Aarhus University.

Christiansen, P. M., & Nørgaard, A. S. (2003). Faste forhold—flygtige forbindelser. Stat og interesseorganisationer i 20. århundrede. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Christiansen, P. M., & Klitgaard, M. B. (2008). Den utænkelige reform. Strukturreformens tilblivelse 2002-2005. Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

Christiansen, P. M., Nørgaard, A. S., Rommetvedt, H., Svensson, T., & Øberg, P.-O. (2010). Varieties of Democracy: Interest Groups and corporatist committees in Scandinavian policy-making. Voluntas, 21(1), 22–40.

Craft, J., & Halligan, J. (2017). Assessing 30 years of Westminster policy advisory system experience. Policy Sciences, 50(1), 47–62.

Craft, J., & Howlett, M. (2013). The dual dynamics of policy advisory systems: The impact of externalization and politicization on policy advice. Policy and Society, 32(3), 187–197.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Folketinget. (2020). Beretning (nr. 4) afgivet af Udvalget for Forretningsordenen den 23. juni 2020: Beretning om gennemførelsen af en udredning om håndteringen af covid-19. Folketinget.

Folketinget. (2021). Håndteringen af covid-19 i foråret 2020. Rapport afgivet af den af Folketingets Udvalg for Forretningsordenen nedsatte udredningsgruppe vedr. håndteringen af covid-19. København: Rosendahls a/s.

Gravengaard, G., & Rendtorff, A. M. (2020). Forskningskommunikation. En praktisk håndbog til eksperter og forskere. Samfundslitteratur.

Grønnegaard Christensen, J., & Mortensen, P. B. (2016). I politikkens vold. Offentlige lederes vilkår og muligheder. Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forlag.

Hustedt, T., & Veit, S. (2017). Policy advisory systems: Change dynamics and sources of variation. Policy Sciences, 50, 41–46.

Kelstrup, J. D. (2016). The Politics of Think Tanks in Europe. Routledge.

Kelstrup, J. D. (2017). Quantitative differences in think tank dissemination activities in Germany, Denmark and the UK. Policy Sciences, 50, 125–137.

Kelstrup, J. D. (2020). Policyprofessionelle i danske tænketanke: uddannelse, erhvervserfaring og synlighed i Folketinget og landsdækkende aviser. Politica, 52(1), 59–75.

Ministry of Finance. (2020). “Kommissorium for økonomisk ekspertvurdering af udfasning af hjælpepakkerne”, May 14 2020. Ministry of Finance.

Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis—New Public Management, Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State. Oxford University Press.

Poulsen, B., & Aagaard, P. (2020). Policyprofessionelle i Danmark. Politica, 52(1), 5–22.

Schmidt, B., & Christensen, J. G. (2016). Embedsmænd som dydens vogtere eller demokratiets tjenere? Politica, 48(4), 373–391.

Streeck, W., & Schmitter, P. C. (1985). Private Interest Government. Beyond Market and State. SAGE-series in Neo-Corporatism. Sage Publications.

Strukturkommissionen. (2004). Strukturkommissionens betænkning. Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet.

Togeby, L., Andersen, J. G., Christiansen, P. M., Jørgensen, T. B., & Vallgårda, S. (2003). Magt og demokrati i Danmark—Hovedresultater fra Magtudredningen. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Økonomi & Politik. (2018). “Dansk folkestyre to årtier efter magtudredningen”. 91. Årgang, No 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kallestrup, M. (2022). Restrained Wisdom or Not? The Advisory Roles of Political Scientists in Denmark. In: Brans, M., Timmermans, A. (eds) The Advisory Roles of Political Scientists in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86004-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86005-9

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)