Abstract

This chapter seeks to explore the role of political scientists within the UK’s policy advisory system through a three-stage process. The first stage seeks to map out the topography of the policy advisory system and assess the extent and nature of the discipline’s historical role and position. It concludes that a combination of demand-side and supply-side variables generally ensured that political scientists played a fairly limited role during the second half of the twentieth century. The second stage explores the twenty-first-century shift driven by the meta-governance of higher education that focuses on non-academic impact and engagement through the analysis of data collected from the impact case studies submitted to the Politics and International Studies panel within the 2014 Research Excellence Framework. This data provides significant insights into the role that political scientists have played within the UK’s policy advisory system. The third section presents, analyses and compares the data collected by the ProSEPS survey of political science with the REF2014 data. This chapter not only provides another layer to our understanding of the role that political scientists play in terms of policy advice but also broadens the analytical lens to a wider cross-section of scholars in its exploration of motivational drivers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

It is possible to identify at least three inter-related streams of scholarship on the discipline of political science (or political studies as it is generally known in the United Kingdom).Footnote 1 The first is a historical strand that charts the emergence and early ambitions of the discipline and is reflected in works such as Stefan Collini, Donald Winch and John Burrow’s The Noble Science of Politics: A Study in Nineteenth Century Intellectual History (1983) and Robert Adcock, Mark Bevir and Shannon Stimson’s Modern Political Science: Anglo-American Exchanges Since 1880 (2007). The second is a more critical stream of work that explores and critiques the evolution of the discipline during the twentieth century. David Ricci’s The Tragedy of Political Science: Politics, Scholarship and Democracy (1984) and Gabriel Almond’s A Discipline Divided: Schools and Sects in Political Science (1990) form essential reference points within this second seam. This flows into a third stream of more recent scholarship that seeks to build upon the existence of long-standing conflicts, concerns and contradictions by focusing on re-establishing a more explicit link between ‘the study of’ politics and democracy and ‘the practice of’ politics and democracy Key contributions within this body of work would include Sanford F. Schram and Brian Caterino’s Making Political Science Matter (2006), Gerry Stoker, B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre’s The Relevance of Political Science (2015) and Rainer Eisfeld’sEmpowering Citizens, Engaging the Public: Political Science for the Twenty-First Century (2019). Taken together, what this body of work highlights is the existence of a long-standing and continuing schism within the field about how to balance the need for scientific objectivity, intellectual independence and professional autonomy, on the one hand, while also demonstrating the social relevance, public benefits and policy impact of political science, on the other. This tension or gap provides the focus of this chapter as it explores the role of political scientists within the UK’s policy advisory system.

One of the main challenges in terms of exploring this topic in the past has been the absence of any reliable data about how political scientists seek to engage with policy-making processes or even contribute to public debates about specific policy controversies or options. This study responds to this challenge by exploring two new datasets which each in their own ways shed light on the complex network of channels through which political scientists seek to operate within policy advisory systems. The first dataset is unique to the UK and utilises Claire Dunlop’s analysis of the 181 ‘impact’ case studies submitted to the ‘Politics and International Studies’ sub-panel of the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF2014) (Dunlop, 2018). The second dataset is the ProSEPS comparative survey of political scientists that was conducted during 2018–2019 and that included 33 countries. Taken together these sources of data lead us to offer three main arguments:

-

1.

When viewed from a comparative perspective, the UK political science community would appear to be active and engaged when it comes to policy advice.

-

2.

This reflects the changing meta-governance of higher education in the UK and the emergence of a powerful and externally imposed ‘impactagenda’ during the last decades.

-

3.

This agenda is rippling-out internationally and presents both opportunities and challenges for political science that demand urgent exploration and discussion.

In order to substantiate these arguments this chapter is divided into three main sections. The first section focuses on the historical evolution of the policy advisory system in the UK and the position of political scientists within it. The main conclusion of this opening section is that political science has traditionally not been a major actor within the policy advisory system until the past few decades. The second section adopts a locational model and utilises data from REF2014 to assess how political scientists have claimed to have had an impact within the policy advice system. This reveals an extensive range of engagement strategies and pathways to impact, many of which pre-date the formal introduction of non-academic impact as a component of the national audit framework. The third and final section drills down still further by utilising original ProSEPS survey data to explore not just how and when political scientists engage with policy-makers but also why.

2 The Policy Advisory System in the United Kingdom

The focus of this chapter is on the policy advice role(s) played by members of the political science community in the UK. In terms of charting these roles and mapping the main interfaces or ‘docking points’ between political scientists and policy-makers, the work of Jonathan Craft and Michael Howlett on ‘policy advisory systems’ provides a valuable analytical lens (Craft & Howlett, 2012). Policy advisory systems are structures of ‘interlocking actors, with a unique configuration in each sector and jurisdiction, who provide information, knowledge and recommendations for action to policy makers’ (Craft & Howlett, 2012, p. 80). Advice in such systems is seen as flowing from multiple sources, at times in intense competition with each other, with decision-makers sitting in the middle of a complex web of advisory actors. Subsequent research on policy advice has focused attention on both the policy advisory system as a unit of analysis per se and the activities of various actors (Hustedt & Veit, 2017). Policy advice can, through this lens, be interpreted quite simply as ‘covering analysis of problems and the proposing of solutions’ (Halligan, 1995, p. 139). The benefit of this approach is that studies have gradually expanded its analytical lens away from the behaviour of individual advisors and advisory practices to encompass a far more synergistic frame that acknowledges the dialectical manner in which various policy advice pathways interact (Aberbach & Rockman, 1989; Craft & Howlett, 2013). As an approach it also focuses attention on differences in tempo, intensity and sequencing, but the role of academics, in general, or political scientists, in particular, as a discrete sub-set of actors within policy advisory systems has not been the focus of sustained analysis.

The UK is generally considered an archetypal power-hoarding majoritarian democracy (Lijphart, 2012). Although recent reforms have adjusted the constitutional infrastructure from one of ‘pure’ to ‘modified’ majoritaranism, the political culture remains informed by a low-trust, high-blame and adversarial mind set (see Flinders, 2009). A historical preference for ‘responsible government’ (i.e. strong, stable, centralised, insulated, etc.) over ‘representative government (i.e. participatory, open, devolved, etc.) has led to the emergence of politico-administrative arrangements that, unlike consociationalist countries, have traditionally done little to facilitate widespread engagement in the policy-making system. The UK was, and to some extent remains, a ‘winner-takes-all’ democracy and ministers enjoy high levels of flexibility in relation to re-shaping government structures (Kelso, 2009, p. 223). The pluralist character of Dutch or even German politics and policy-making therefore provides something of a counter-point to the conventionally elitist character of British politics.

That is not to suggest, however, that the political advisory system has not changed in recent decades. Studies of the policy advisory system in the UK have generally revealed the gradual erosion of public service policy capacity and a general trend of declining substantive experience in favour of generalist and process-heavy forms of policy work (Edwards, 2009; Foster, 2001; Gleeson et al., 2011; Page & Jenkins, 2005; Tiernan, 2011). A distinctive shift occurred in the 1980s with the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, promoting a strong emphasis towards the externalisation and politicisation of policy advice due to her lack of confidence in both the neutrality and capacity of the permanent civil service (and to a large extent of most social scientists) (Foster, 2001; Fry, 1988). The closure of the Royal Institute of Public Administration (RIPA) in 1992 was arguably emblematic of a deeper set of changes within the policy advisory system. Originally established in May 1922, RIPA had sought to bridge the academic-practitioner divide in order to foster higher standards of both scholarly understanding and professional development. Its demise has been well documented, but the critical element for this section is that there was no appetite amongst ministers or senior officials to step-in to save RIPA with what would have been a very modest resource allocation (see, e.g. Rhodes, 2011 and Shelley, 1993). As a result, the 1990s witnessed a distinct shift away from traditional policy advisory structures towards a hybrid system in which the role of politically appointed advisers and independent think tanks increased at the expense of long-standing constitutional ties that focused on the relationship between ministers and their senior officials (Campbell & Wilson, 1995; Foster, 2001; Halligan, 1995; Page & Jenkins, 2005). Patrick Diamond has referred to this general decline of internal/official capacity combined with an increased reliance on external/partisan advice as a ‘crisis of Whitehall’ (Diamond, 2014).

Concerns about the lack of professional capacity vis-à-vis policy advice in the UK have consequently been the focus of a series of critical reports by the National Audit Office (NAO) and the Institute for Government (IFG). For example, the IFG’s report Policy Making in the Real World: Evidence and Analysis (2011) notes that ‘[t]here are signs that the policy profession is starting to address some of these problems. But there is considerable work to be done in order to create a realistic, coherent approach to improving policy making’ (Institute for Government, 2011, p. 5). Reports also found that the Civil Service has been struggling to effectively support and implement new policy-making and that departments frequently have ad hoc policy strategies that are often fragmented (Institute for Government, 2017; National Audit Office, 2017). The existing research base suggests that the evolution of the policy advisory system in the UK has become more distributed with an expansion of (1) internal [partisan] governmental capacity (political advisory systems, special advisers, new central policy units, etc.) and (2) external sources of advice (think tanks, commissions, task forces, review groups, etc.) at the expense of the traditional internal [neutral] public service sources (senior officials, departmental briefs, etc.) (Craft & Halligan, 2017).

In order to understand the data presented in this chapter, it is necessary to contextualise it through a very brief focus on the history of British political studies and also upon the changing meta-governance of higher education in the UK.

As Jack Hayward, Brian Barry and Archie Brown’s The British Study of Politics in the Twentieth Century (1999) and Wyn Grant’s The Development of a Discipline (2010) each in their own ways serve to illustrate, the study of politics in the UK is distinctive in at least two ways. First, it exhibits a highly pluralist approach to theory and method which is arguably more diverse and inclusive than is generally found within the field in other countries. Tight disciplinary ‘boundary management’ has never been a core concern in the UK; to the extent that questions have been raised about ‘whether political studies—or even political science—is in fact a discrete discipline’ (Warleigh-Lack & Cini, 2009, p. 7; Gieryn, 1999, p. 27). The second characteristic revolves around what Jack Hayward and Philip Norton have described as a long-standing tension in the Aristotelian conception of politics as a ‘master science’ between ‘a theoretical preoccupation with political science as a vocation on the one hand and public service as a vocation on the other (Hayward & Norton, 1986, p. 8)’. As a result, ‘an ineffectual zig-zag has taken place in the no man’s land between rigidly separated theoretical and practical spheres (Ibid.)’.

At a broad level, it is therefore possible to suggest that historically political scientists have not been active or engaged members of the policy advisory system in the UK. That is not to suggest that some specific scholars or sub-fields have not played an active role in producing theoretically informed policy relevant research but disciplinary histories generally identify the existence of a significant ‘gap’ between politics or policy-making ‘as theory’ and politics or policy-making ‘as practice’, especially due to the perception that the specialisms of political scientists could impede them from effectively contributing to a national, and therefore more generalised, policy process (Smith, 1986). Even when the policy advisory system was recalibrated under Mrs Thatcher, the politicisation that accompanied this shift was unlikely to create opportunities for an academic community that was overwhelmingly left-wing in political orientation (see, e.g. Halsey, 1992). The exception to this statement was the significant role of academic economists within key right-wing think tanks such as the Institute for Economic Affairs and the Adam Smith Institute (Harrison, 1994). Political scientists were, on the whole, ‘outsiders’ and therefore rarely engaged with or appointed to the main arenas or processes that tend to constitute policy advisory systems (i.e. advisory agencies, consultancies, special adviser roles, commissions of inquiry, etc.).

If the demand-side variables for political science to engage in the policy advisory system have traditionally been weak, then the supply-side variables have also arguably been problematic as the vaunted ‘professionalisation’ of the discipline in the 1990s and into the 2000s has very often veiled the emergence of an emphasis on a ‘scientific’, ‘objective’ and increasingly quantitative disciplinary emphasis. Not only did this mean that there were very few incentives for political scientists to engage in policy advisory roles or processes but it also meant that the outputs of the discipline were increasingly specialised and inaccessible to non-academic readers. The risks of this ‘road to irrelevance’ had been highlighted fifty years earlier in Bernard Crick’s first book—The American Science of Politics (1959), and by the 2010s a major internal debate had erupted about the policy relevance and social impact of the discipline (Flinders & John, 2013). At the same time, ministers and their officials were increasingly committed to ensuring that publicly funded research was being utilised within policy advisory structures. This complemented a broader shift towards ‘evidence-based policy’ and the reorientation of universities towards the transfer, translation and commercialisation of academic knowledge (see Rip, 2011). In 2010 the Higher Education Funding Council for England commissioned a series of impact measurement pilots designed to produce narrative-style case studies (Bandola-Gill & Smith, 2021) which ultimately led to the endorsement of non-academic impact as a key performance indicator within the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (Research Excellence Framework, 2010; see also Watermayer, 2014; Brook, 2017; Wilkinson, 2018; Watermeyer & Chubb, 2019). Societal impact was broadly defined

as an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia. [Italics added]

The meta-governance of higher education had shifted significantly as a raft of incentives to encourage academics to engage with potential research-users were suddenly put in place (placement opportunities, knowledge-exchange funding, changes to promotion criteria, ‘impact acceleration accounts’, etc.) by institutions (Bandola-Gill, 2019). Three elements of a rapidly changing policy advisory system are notable. First, the main public funder of social and political science, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), has in recent years focused on the creation of increasingly innovative forms of research infrastructure that are designed to facilitate mobilisation and to ensure the mobility of people, ideas and talent across traditional professional, disciplinary and organisational boundaries. These include a national network of ‘What Works’ centres that are generally co-funded by research-users and a host of ‘hubs’ or ‘nexus networks’ that operate at the interface of academe and society (see Box 15.1, below) (Great Britain, Cabinet Office, 2019). The second element is that universities have themselves sought to build knowledge-mobilisation capacity, and this has generally occurred through the rapid proliferation of institutes of public policy. In 2019 this led to the creation of the Universities Policy Engagement Network (UPEN) as a national platform for engaging with a number of policy arenas. In July 2019 a new report by a number of UPEN members—Understanding and Navigating the Landscape of Evidence-based Policy—called for the establishment of a new National Centre for Universities and Public Policy to support an ongoing culture change around valuing academia policy engagement (Walker et al., 2019). The third element is that research-users have created new teams and launched new initiatives in order to foster academic engagement. As the Institute for Government’s report of June 2018—How Government Can Work with Academia—highlighted, this includes the Department for Education’s creation of a pool of academic researchers that officials use to commission rapid evidence reviews, and the Cabinet Office has set up a unit, sponsored by universities, that helps senior academics to work part-time with departments to develop policy. In addition to this all government departments now publish a regularly updated list of ‘areas of research interest’ which is designed to signpost specific areas where policy-makers would welcome academic engagement, the vast majority of which tend to be areas that demand input from the social and political science community (Great Britain, Government Office for Science and Cabinet Office, 2019). This shifting landscapes underlines the manner in which a new ‘political economy of impact’ has emerged in the UK (Dunlop, 2018, p. 272). The ‘ineffectual zig-zag’ (mentioned above) had suddenly taken a very sharp turn towards engagement with potential research-users, and although the merits and risks of this ‘zig’ or ‘zag’ divided opinion, there is little doubt that it led to a sharp shift in behaviour. In order to explore this shift, the next sub-section combines the analysis of REF2014 impact data with the locational model of policy advice.

Box 15.1 United Kingdom in a Changing Europe: an example of the advisory role of political scientists in current debates

The award-winning United Kingdom in a Changing Europe Initiative (UK-ICE) started in 2014 and aims to ensure that public and policy debates about Brexit are underpinned by access to world-class social and particularly political science. It is a fairly unique investment by the Economic and Social Research Council in that it is focused primarily on the translation and dissemination of existing research rather than on the production of new knowledge and data. The UK-ICE initiative has gained a reputation as a reliable and impartial source of information that operates at the intersection or nexus between the academy and the policy advisory system.

The structure of the UK-ICE is also innovative in that it works through a hub-and-spoke model with a core investment to fund a small strategic team at King’s College, London, which is charged with overseeing and co-ordinating a network of fellowships and grants that are based across the United Kingdom. The main UK-ICE team also acts as the main gateway for media and public inquiries and also maintains a highly professional and accessible website. It therefore acts as a highly agile and responsive ‘one-stop shop’ for any individual, group or organisation that is keen to understand the existing evidence base on any specific Brexit-related topic. Under the guidance of its director, Professor Anand Menon, the UK-ICE has emerged as a source of commentary and analysis that is widely respected and trusted not just by journalists, commentators and civic groups but also (critically) by actors and activists on both sides of the Brexit debate. This has been a remarkable achievement in a highly polarised area of policy and in a context where the public trust in experts has been questioned.

The UK-ICE programme has maintained high-level relationships in Whitehall and Westminster, in addition to working with politicians and policy-makers in the devolved territories and also in Brussels. Engagement has taken the form of formal workshops, informal meetings, masterclasses, briefing papers and the provision of data and information. This engagement has subsequently fed back into scholarly understandings of policy challenges, while also expanding the existence of high-trust professional networks at a critical time for the country. In 2019 the ESRC announced a major new package of funding to continue the UK-ICE programme until 2021.

3 The Locational Model of Policy Advice

The focus of this chapter is on the role of political science within the British policy advisory system. The previous sub-section suggested that levels of engagement had up until recent decades generally been fairly low. This reflected a rather closed and elitist political culture, the dominance of right-wing governments during the final decades of the twentieth century and a lack of professional incentives to actually engage with policy-makers. This dovetailed with a strangely British academic culture that often looked down upon those scholars who were willing to ‘dirty their hands’ in the grubby world of politics or even engage with the public via the media (Grant, 2010, pp. 44–45). This section utilises a locational model adapted by Blum and Brans (2017) from Halligan (1995) to describe how and in which policy advisory arenas political scientists engage with policy advice (see Figure 2.1, Chap. 2).

The main aim of this section is to utilise Dunlop’s analysis of the 181 impact case studies that were submitted to the ‘Politics and International Studies’ sub-panel in REF2014 as a proxy measure of where in the policy advisory system political scientists have been most active (Dunlop, 2018).Footnote 2 We cannot claim that this approach represents a complete account of the role and visibility of political science within the UK’s national policy advisory system, but we do suggest that it offers a significant, distinctive and original starting point from which to explore the topic. We relate five specific findings to Blum and Brans’ locational model:

-

1.

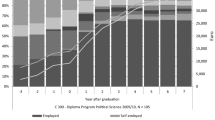

In the UK engagement within the policy advisory system is dominated by four specific sub-fields within political science: Public Policy and Administration (23%), Elections and Parliamentary Studies (17%), Security (14%), and Human Rights and Conflict (12%) (see Fig. 15.1).

-

2.

The analysis of REF2014 case studies reveals long-established policy advisory relationships that existed before the 2008–2013 assessment period.

-

3.

Political scientists have worked with a broad range of beneficiaries within the policy advisory system and have utilised a number of ‘pathways to impact’ or ‘tools of engagement’ (Tables 15.1 and 15.2).

-

4.

A significant amount of policy advice is aimed ‘above’ or ‘below’ the nation state in ways that pose a challenge for the locational model as currently conceived.

-

5.

Where gaps appear to exist in the policy advisory system vis-à-vis political science, they relate to working with the public and with the business sector.

The remainder of this sub-section takes each of these five issues in turn. The first of which is simply to note that when it comes to operating within the policy advisory system, four areas of the discipline dominate (see Fig 15.1, below) and the main beneficiaries of this activity are found within the ‘internal government arena’ (notably providing research-based advice to government departments, public agencies and parliamentary committees) and the ‘external lay arena’ (to think tanks, charities and non-governmental organisations and international organisations).

Politics and international studies impact case study sub-fields (in percentages)—UK. (Source: Dunlop, 2018, p. 274)

The second insight emerging from this analysis is that the underpinning research being fed into policy advisory systems was based upon work and academic-user relationships that very often pre-dated the REF2014 assessment period. Indeed, 43% (N=72) of the case studies were based on projects and relationships developed over a decade or more before the 2014 deadline, and 40% (N=66) were between five and nine years before the cut-off point. This suggests that irrespective of the concern expressed by several members of the discipline about the challenges faced by political scientists who wanted to engage with policy-makers in the 1990s and 2000s, a significant number were in fact able to develop and maintain relationships long before the impactagenda came into fashion (Bevir & Rhodes, 2007). What’s also interesting (and the third insight) about Dunlop’s analysis is the manner in which it indicates a broad range of beneficiaries within the policy advice system and a number of ‘pathways to impact’ or ‘tools of engagement’ (Tables 15.1 and 15.2, below). The ‘polite or contemptuous rejection of political science by those in authority’ that was discussed in the previous section—or what Wyn Grant labelled ‘reticent practitioners’—appears to have been replaced by a more open and diverse institutional architecture. Moreover, the data also suggests that UK political scientists are becoming far more proactive and entrepreneurial in terms of identifying and initiating contact with potential research-users. It also suggests that a significant number of UK political scientists operate as ‘boundary-spanners’ in the sense that hold academic appointments alongside significant roles within political parties, think tanks, NGOs or charities (Hoppe, 2009). Over a fifth of the impact case studies (21% N = 35) involved academics with non-research-related commitments of this nature.

One of the weaknesses of the locational model, however, as currently devised is that it struggles to accommodate the role of political science within policy advisory systems above or below the nation state. This is particularly restrictive in the case of the UK where the evidence suggests that a large amount of engagement occurs at the sub-national and local level or at the European and international level. ‘This is not simply a story about UK-based academics working with UK-based policy-makers’, Dunlop emphasises ‘Internationalisation is very strong: 64% of cases (N=106) involve non-UK governments as beneficiaries, 45% (N=74) international organisations and 58% of all cases (N=96) claim some sort of international impact’ (Dunlop, 2018, p. 277). The fifth and final insight emerging from Dunlop’s analysis of the REF2014 impact case studies submitted to the ‘Politics and International Studies’ panel is the relative lack of engagement in two key areas. The first relates to business and industry links (just 5% of cases, N=9) which is possibly not surprising given the widespread professional concern that the impact agenda is linked to a dominant neo-liberal ideological agenda. It could also be a result of the historically developed ‘pathways to impact’ discussed above, where the potential for impact is largely determined by the presence of relationship between the producers and users of research. Therefore, if the political scientists engaged historically with policy-makers, the access to the private sector might be challenging and consequently rare. What is more surprising, especially given the discipline’s long-standing emphasis on citizenship and the promotion of civic engagement, is the lack of political science case studies that claim direct engagement with and impact upon the public (22% N=37) (ESRC, 2007). This was an issue that the government’s own official review of the 2014 REF process highlighted but may actually be explained as being indicative of the methodological challenges faced by any scholar or institution who seeks to make claims regarding the existence of causal links between a specific piece of research, on the one hand, and changes in the orientation of a specific public debate, public attitudes or even public behaviour, on the other. Put slightly differently, the REF2014 case studies do not necessarily mean that political science is not engaging with the public (see below) but simply that institutions are making strategic decisions about the type of impact they attempt to claim. It could also be a consequence of specific measurement approach, where the focus on a specific change is not conducive to projects aimed at the public, as these are not easily documented and traced (Bandola-Gill & Smith, 2021; Smith & Stewart, 2017). One way of assessing the true role of political scientists within the policy advice system (broadly defined) would be to step away from the rational instrumentalities of REF2014 (and soon to be REF2021 with an even higher ‘impact’ weighting) and to explore data collected directly from academics. In order to do this the next section examines the ProSEPS survey data for the UK.

4 Advisory Roles Adopted by Political Scientists

The UK is arguably unique when it comes to assessing the role of academics within the policy advisory system. This stems from the manner in which ‘impact’ is now formally and explicitly institutionalised within the regulatory landscape of higher education. A note of caution is, however, required. The data presented and discussed in the previous section relates solely to the activities of those political scientists who were selected by their institutions to be assessed within REF2014. It therefore provides a partial account or a snapshot of disciplinary activity and as only one impact case study was required for every ten members of staff, and not all institutions submitted returns to the Politics and International Studies Panel, the generalisability of this data is limited. The REF2014 data therefore provides a valuable and unique lens on the role of the discipline within the British policy advisory system while at the same time being particularly hard to benchmark in terms of the degree to which it is representative of engagement at a broader level. This is a critical point. It is difficult to know from the analysis of the REF2014 impact case studies if they provide either an account of the achievements of a hyper-engaged minority of scholars or whether they actually understate the true extent of policy-related activity for the simple reason that the social impact of more diffuse forms of publicengagement (as opposed to more specific policyengagement) is far harder to prove in the demonstrable and auditable manner the assessment process requires.

This section engages with these epistemological and methodological challenges by presenting the insights of a new data set that was collected through a major international survey of political scientists. Although the UK response rate was fairly low (400 responses from a disciplinary community of around 3000 or 13.5%), it offers a credible, complementary and fine-grained lens through which to explore the current role of political science within the UK’s policy advisory system. This is largely because the dataset engages beyond those who were selected to deliver REF2014 impact case studies. The main conclusion emanating from the ProSEPS database is that, as might have been expected from the emergence of the ‘impact agenda’, British political scientists do report a relatively high degree of engagement with policy-makers, and there appear to be a relatively small number of hyper-engaged scholars (see Table 15.3, below). Underlying insights that resonate with Dunlop’s analysis of the REF2014 case studies include the following:

-

1.

Political scientists utilise both formal and informal modes of engagement, with policy advice in areas that are linked to a small number of sub-fields being most common (Table 15.4).

-

2.

The main beneficiaries exist within the governmental arena or with think tanks, charities and civil societyorganisations (Table 15.5).

-

3.

A significant amount of policy engagement by political scientists occurs ‘above’ and ‘below’ the nation state (Table 15.6) and a range of ‘pathways to impact’ or ‘tools of engagement’ are deployed (Table 15.7).

-

4.

Most political scientists describe their policy role as either an ‘expert’ or ‘opinionator’ with very few describing themselves as a ‘pure academic’ and even fewer as a ‘public intellectual’ (Table 15.8).

-

5.

The motivations for engaging within policy advisory systems are complex, multifaceted and cannot be explained solely with reference to the REF framework (Tables 15.9 and 15.10).

Overall, the British political scientists reported a relatively high engagement with policy-makers—only a minority of academics reported not engaging in any form of advisory activities. The most popular type of advice—providing data and facts—was given once a year or less frequently by 60% of academics. Furthermore, the academics reported that they engage at least once a year or less often in policy analysis (57%), policy evaluation (60%) and consultancy (54%). There is also a considerable group of academics who engage with various forms of advice very frequently—once a week or once a month. For example, this group of academics engaged in policy analysis (15% of respondents), providing data and facts (10%) and policy evaluation (13%) at this frequency. Nevertheless, there are some areas of policy advising in which the academics did not participate, most strikingly 70% of academics reported they have never made forecasts or conducted polls. The UK academics seem to be more divided with regard to conducting consultancy (35% of the respondents has never done it) and offering value judgements (37% reported never engaging with this activity). The UK academics appear to be split, with large groups of this population either engaging in these two types of activities or avoiding them completely. This is best illustrated by the approach to value judgements—37% of the respondents avoid it completely and yet 46% of the UK academics reported producing value judgements once a year or less frequently and 13% did it at least once a month or once a week. This finding might suggest that some types of advisory practices were seen to be more politicised than others (such as policy evaluation or analysis) and as such, they were avoided by a larger group of political scientists.

In terms of the policy areas where political scientists were most active, the data highlights three main areas—international affairs, development aid, EU and government and public administration organisation and electoral reform—which broadly dovetail with the main sub-fields that were most visible in Dunlop’s analysis of the REF2014 case studies (see Fig. 15.1, above).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, and again in line with the REF2014 analysis, the main beneficiaries highlighted in the ProSEPS data were civil servants (with 51% of respondents reporting having engaged with them), but what was possibly more surprising was the popularity of think tanks (47%) and civil societyorganisations (48%) as the venue for advisory activities (Table 15.6, below). This popularity might be explained by the perceived expert status of these organisations which might be better aligned with the preference of the academics to offer data and facts, rather than value-laden analysis. The least popular target groups of advice were executive politicians (23%), political parties (21%) and the interest groups from the private sector (25%). This finding might point again to the importance of the autonomy and impartiality of the political scientists in the UK who prefer engagement with less political and more expertise-based target groups. This is especially interesting in the case of think tanks which are portrayed—both by media and by the UK politicians as expertise-driven organisations (Hernando, 2019). However, the political neutrality of think tanks is largely challenged with research showing that these types of organisations are in fact closely aligned with the dominant coalitions (Stone, 1996). Consequently, think tanks in the UK produce what Marcos González Hernando called ‘politically fit expert knowledge’ rather than politically neutral knowledge (Hernando, 2019, p. 12).

What is also interesting from a locational model perspective and which once again chimes with the REF2014 analysis is the critical role that legislative scrutiny committees appear to play as an important ‘docking point’ (39%) between political scientists and policy-makers. This may reflect the manner in which investments have been made in order to build research infrastructure to facilitate interaction, specifically through the creation of a Social Science Team within the Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology (POST) in 2011 (Great Britain, POST 2019). The Role of Research in the UK Parliament was a major report published by POST in 2017 which, although not focused specifically on political science, did provide huge detail on the ways that academics engaged with parliament and which parts of the legislature they tended to work with (see also Kenny et al., 2017). It also revealed that parliament featured in 20% of REF2014 impact case studies but that major challenges existed in terms of increasing the spread of academics that were willing to engage and making sure they had the skills to submit evidence in an accessible, timely and relevant manner (see also Kenny, 2015).

What also becomes clear from the ProSEPS data is that there is no single policy advisory system in the UK but a number of multi-layered and nested systems linked to devolved territories in which political scientists operate. As Table 15.6 illustrates, the national level remains the main focus of activity but with significant levels of engagement ‘above’ and ‘below’ the nation state (again chiming with Dunlop’s analysis of REF2014). Engagement by political scientists within the Scottish parliament and National Assembly of Wales appear from the available evidence to be particularly strong, and this may reflect a number of issues including the existence of a different and more open political culture at the sub-national level and the simple benefits of scale in terms of facilitating formal and informal networking (Hewlett & Hinrichs-Krapels, 2017; McQuillan, 2017).

The ‘pathways to impact’ or ‘engagement tools’ highlighted in the ProSEPS data also complements the REF analysis discussed in the previous section. The added insight here, however, relates to frequency and the apparent existence of a clear preference for a once-a-year communication via publications (40%), research reports (31%), policy reports (30%) and blogs and social media (30%). The least popular channel was an organisation of training courses for policy-makers, 38% of the respondents claimed they have never engaged in this type of activity. However, the vast majority of the respondents used these communication channels at least once, most frequently once a year for most of the channels.

This focus on beneficiaries, frequencies, pathways and levels flows into a final focus on a broader set of questions that take us well beyond Dunlop’s REF2014 analysis and instead focus on how political scientists self-define their contemporary role vis-à-vis the policy advisory system and what are the drivers of the activities that have been revealed in this data. As Table 15.8 illustrates, less than 15% of British political scientists described the type of advisory role they perform as that of being a ‘pure academic’, whereas over 50% thought of themselves as ‘opinionators’. However, as the ProSEPS study defines the opinionator as one ‘who does not write extensive publication material, but mostly focuses on opinion editorial and newspapers columns, tv and radio interviews’ (see Chap. 2), then this definition does not correspond with the importance of publications in UK academia. From the earliest stages in their career, academics are encouraged to conduct high-quality research through single or lead authored publications (especially as this is an important criterion of the REF assessment) (see, e.g. The British Academy 2016). A low number of political scientists in the UK would be reluctant to self-identify as a ‘pure academic’ (14.6%) due to the formal adoption of ‘impact’ within the regulatory landscape of academia, as outlined above. The role of an (technical) expert, whose advice is normally ‘offered to policy makers in the administration, committees, think tanks’ is more common in the UK system, with 27.1% declaring to take on this role. Given the increasing need in the UK for academics to provide evidence of impact and public engagement with their research, it is not surprising that the majority of political scientists (80.6%) who partook in the survey self-identified as either an ‘opinionator’ or an ‘expert’. However, it is surprising that more did not self-identify as ‘public intellectuals’ (4.8%), as it was defined as ‘a hybrid between the expert and the opinionator’. This low selection could be due to the time and effort required for engaging with both ‘policy makers in the administration, think tanks, [and] committees’ as well as ‘politicians and policy makers, the general public, [and] journalists’. Those who identify as the ‘public intellectual’ would have done so because they view themselves as engaging in this way ‘very frequently’ and through both informal and formal channels. Whilst this low percentage of ‘public intellectuals’ could be a result of the manner in which modesty is extolled as a virtue in British culture, it could also be due to the way UK academics in the twenty-first century are facing increasing ‘demands on their time’ where the ‘complexity of those demands are changing and escalating almost exponentially’, as described by Light and Cox (2009).

What Table 15.8 suggests is that the vast majority of British political scientists do self-define themselves in terms of having some form of role within the policy advisory system, either as a technical expert feeding evidence and data into debates or the policy-making process or as a potential pundit helping to stimulate and inform public debates more broadly. But what drives or underpins this commitment to visibility or what might be termed engaged scholarship?

Tables 15.9 and 15.10 suggest that the emergence of an explicit and externally audited ‘impactagenda’ in the UK cannot on its own explain the levels of activity highlighted in this study and related reports. Indeed, what the ProSEPS data indicates is the existence of a deep cultural attachment within British political science to undertaking research that has an impact far beyond the lecture theatre or seminar room. Two-thirds of respondents suggest that political scientists should become engaged in policy-making and an even higher proportion agreed that political scientists had a professional obligation to engage in public debate. Nine out of ten respondents disagreed with the suggestion that political scientists should refrain from direct engagement with policy-makers, which might reflect the relatively low levels of attachment to the notion of being a ‘pure’ academic (Table 15.8, above). Table 15.10 develops this through its indication that although promotion structures now tend to reward impact-related contributions, extrinsic ‘public good’ motivations far outweigh intrinsic self-interested motivations. Once again two-thirds of respondents viewed engagement as a professional responsibility of political scientists to the public and nearly half felt that making a contribution to society was ‘absolutely important’.

5 Conclusion

These findings regarding normative drivers and the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations bring this chapter full circle and back to the opening section’s focus on the existence of a long-standing tension within British political science between its scientific aspirations as opposed to its public service ethos. In the second half of the twentieth century, political scientists played a limited role in the political advisory system due to the selective nature and established relationship between few academics and Westminster. There also existed a tension between the political scientist who believed in the strictly academic study of politics and the ‘public duty’ of engaging and supporting public policy and democratic processes. This tension was eased by the beginning of the twenty-first century, where the meta-governance of higher education encouraged, supported and recognised the desire of political scientists to engage outside of academia. The incentives for advising were thus made formal and included in the promotion and reward structures for academics. Due to the standardisation brought by the REF, impact on the political advisory system was now included in scholarly performance evaluation in the UK.

What the data that has been presented and discussed in the second and third sections of this study suggest, however, is that in many ways it may well be too simplistic to equate apparently high levels of policy engagement with the introduction of the ‘impactagenda’ from around 2010 onwards. As Dunlop revealed, many political scientists were operating within the policy advisory system long before the assessment system in the UK included an impact component. Indeed, what the ‘long view’ of political science in the UK might actually suggest is a more nuanced interpretation whereby the demands of REF2014 legitimated, incentivised and rewarded a shift towards public service and policy engagement that was in reality a long-standing cultural dimension of the discipline. What this study aims to demonstrate is that the role of political science within the UK’s policy advisory system appears more significant than is generally recognised but that the reasons for this may reflect deep-seated cultural values within the discipline rather than an instrumental response to an external audit regime.

Notes

- 1.

Notwithstanding Mike Kenny’s questioning ‘about whether the very idea of a “discipline” projects a spurious unity, and misleading singularity, on to what are in reality internally diverse and loosely bounded fields of study’ (Kenny, 2004).

- 2.

Note this analysis covers 166 case studies (submitted by 56 universities) as 15 were either confidential or heavily redacted. All case studies are available at Research Excellence Framework (REF). 2019. Search REF Impact Case Studies [online] Research Excellence Framework. [Viewed 16 December 2019]. Available from: http://impact.ref.ac.uk/CaseStudies.

References

Aberbach, J., & Rockman, B. (1989). On the rise, transformation, and decline of analysis in the US government. Governance, 2(3), 293–314.

Bandola-Gill, J. (2019). Between relevance and excellence? Research impact agenda and the production of policy knowledge. Science and Public Policy, 46(6), 895–905.

Bandola-Gill, J., & Smith, K. E. (2021). Governing by narratives: REF impact case studies and restrictive storytelling in performance measurement. Studies in Higher Education, 1–15.

Bevir, M., & Rhodes, R. (2007). Traditions of political science in contemporary Britain. In R. Adcock, M. Bevir, & S. Stimson (Eds.), Modern political science: Anglo-American exchanges since 1880 (pp. 234–258). Princeton University Press.

Blum, S., & Brans, M. (2017). Academic policy analysis and research utilization for policymaking. In M. Brans, I. Geva-May, & M. Howlett (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Comparative Policy Analysis (pp. 341–359). Routledge.

Brook, L. (2017). Evidencing impact from art research: analysis of impact case studies from the REF 2014. Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society, 48(1), 57–69.

Campbell, C., & Wilson, G. (1995). The end of Whitehall: A comparative perspective. Blackwell.

Craft, J., & Halligan, J. (2017). Assessing 30 years of Westminster policy advisory system experience. Policy Sciences, 50, 47–62.

Craft, J., & Howlett, M. (2012). Policy formulation, governance shifts and policy influence: location and content in policy advisory systems. Journal of Public Policy, 32(2), 79–98.

Craft, J., & Howlett, M. (2013). The dual dynamics of policy advisory systems: The impact of externalization and politicization on policy advice. Policy and Society, 32(3), 187–197.

Diamond, P. (2014). A crisis of Whitehall. In D. Richards, M. Smith, & C. Hay (Eds.), Institutional crisis in 21st-century Britain (pp. 125–147). Palgrave Macmillan.

Dunlop, C. (2018). The political economy of politics and international studies impact: REF2014 case analysis. British Politics, 13(3), 270–294.

Edwards, L. (2009). Testing the discourse of declining policy capacity: Rail policy and the department of transport. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 68(3), 288–302.

ESRC. (2007). International benchmarking review of UK politics and international studies. ESRC.

Flinders, M. (2009). Democratic drift. Oxford University Press.

Flinders, M., & John, P. (2013). The future of political science. Political Studies Review, 11(2), 222–227.

Foster, C. D. (2001). The Civil Service under stress: The fall in Civil Service power and authority. Public Administration, 79(3), 725–749.

Fry, G. K. (1988). The Thatcher government, the financial management initiative, and the “new CML service”. Public Administration, 66(1), 1–20.

Gieryn, T. F. (1999). Cultural boundaries of science. The University of Chicago Press.

Gleeson, D., Legge, D., O’Neill, D., & Pfeffer, M. (2011). Negotiating tensions in developing organizational policy capacity: Comparative lessons to be drawn. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 13, 237–263.

Grant, W. (2010). The development of a discipline: the history of the political studies association. Wiley-Blackwell.

Great Britain, Cabinet Office. (2019). What Works Networks [online]. London: Cabinet Office. [Viewed 16 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/what-works-network

Great Britain, Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. (2019). Social Sciences [online]. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. [Viewed 16 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/offices/bicameral/post/post-work/social-sciences/

Halligan, J. (1995). Policy advice and the public sector. In B. G. Peters & D. Savoie (Eds.), Governance in a changing environment (pp. 138–172). McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Halsey, A. H. (1992). Decline of donnish dominion: The British academic professions in the twentieth century. Oxford University Press.

Harrison, B. (1994). Mrs Thatcher and the intellectuals. Twentieth Century British History, 5(2), 206–245.

Hayward, J., & Norton, P. (1986). The political science of British politics. Wheatsheaf Books.

Hernando, M. G. (2019). British Think Tanks after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hewlett, K., & Hinrichs-Krapels, S. (2017). The impacts of academic research from Welsh universities. King’s College London.

Hoppe, R. (2009). Scientific advice and public policy: expert advisers’ and policymakers’ discourses on boundary work. Poiesis & Praxis, 6(3–4), 235–263.

Hustedt, T., & Veit, S. (2017). Policy advisory systems: change dynamics and sources of variation. Policy Sciences, 50, 41–46.

Institute for Government. (2011). Policy making in the real world: Evidence and analysis. Institute for Government.

Institute for Government. (2017). Professionalising Whitehall. Institute for Government.

Kelso, A. (2009). Parliament. In M. Flinders, A. Gamble, C. Hay, & M. Kenny (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of British Politics (pp. 221–238). Oxford University Press.

Kenny, C. (2015). The impact of academia on Parliament: 45 percent of Parliament-focused impact case studies were from social sciences. LSE Impact of Social Sciences Blog. Available from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2015/10/19/the-impact-of-uk-academia-on-parliament/; See also Institute for Government 2018. How Government can work with Academia, London: IfG.

Kenny, C., Rose, D. C., Hobbs, A., Tyler, C., & Blackstock, J. (2017). The Role of research in the UK Parliament. Houses of Parliament.

Kenny, M. (2004). The Case for Disciplinary History. BJPIR, 6(4), 565–583.

Light, G., & Cox, R. (2009). Learning and teaching in higher education: The reflective professional. Sage Publications.

Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy. Yale University Press.

McQuillan. (2017). Case study experiences of REF in the Scottish Parliament. Internal review by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre.

National Audit Office. (2017). Capability in the Civil Service, HC 919. National Audit Office.

Page, E., & Jenkins, B. (2005). Policy bureaucracy. Government with a cast of thousands. Oxford University Press.

Research Excellence Framework. (2010). Research Excellence Framework impact pilot exercise: Findings of the expert panels. REF. https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/pubs/refimpactpilotexercisefindingsoftheexpertpanels/

Rhodes, R. A. W. (Ed.). (2011). Public administration: 25 years of analysis and debate, 1986-2011. Wiley-Blackwell.

Rip, A. (2011). The future of research universities. Prometheus: Critical Studies in Innovation, 29(4), 443–453.

Shelley, I. (1993). What happened to the RIPA. Public Administration, 71, 471–489.

Smith, K., & Stewart, E. (2017). We need to talk about impact: why social policy academics need to engage with the UK’s Research Impact Agenda. Journal of Social Policy, 46(1), 109–127.

Smith, T. (1986). Political science and modern British society. Government and Opposition, 21(4), 420–436.

Stone, D. (1996). From the margins of politics: The influence of think-tanks in Britain. West European Politics, 19(4), 675–692.

Tiernan, A. (2011). Advising Australian federal governments: Assessing the evolving capacity and role of the Australian public service. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 70(4), 335–346.

Walker, L., Pike, L., Chambers, C., Lawrence, N., Wood, M., & Durrant, H. (2019). Understanding and navigating the landscape of evidence-based policy recommendations for improving academic-policy engagement. The University of Bath Institute for Policy Research (IPR) and Policy Bristol.

Warleigh-Lack, A., & Cini, M. (2009). Interdisciplinarity and the study of politics. European Political Science, 8(1), 4–15.

Watermayer, R. (2014). Issues in the articulation of ‘impact’. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 359–377.

Watermeyer, R., & Chubb, J. (2019). Evaluating ‘impact’ in the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF): liminality, looseness and new modalities of scholarly distinction. Studies in Higher Education, 44(9), 1554–1566.

Wilkinson, C. (2018). Evidencing impact: a case study of UK academic perspectives on evidencing research impact’. Studies in Higher Education, 44(1), 72–85.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Flinders, M., Bandola-Gill, J., Anderson, A. (2022). Making Political Science Matter: The Advisory Roles of Political Scientists in the United Kingdom. In: Brans, M., Timmermans, A. (eds) The Advisory Roles of Political Scientists in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86004-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86005-9

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)