Abstract

This chapter develops the concept of digital imaginaries in order to examine collective visions of the Chinese nation state that are rooted in the promise of digital technologies and to highlight the crucial relationship between national imaginaries and everyday experiences of digital platforms in China. Drawing on thirteen months of fieldwork in Beijing, I explore the interplay between experiences of digital platforms, the narratives presented by technology companies and government discourses on digitization. To explore this interplay, the chapter focuses on the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba as an important intermediary between Chinese citizens and the government. Alibaba’s self-proclaimed mission to digitally connect and provide opportunities to all Chinese echoes and gives purchase to the Chinese government’s claim that digital technologies can and have unified the socially, ethnically, economically and regionally fragmented space of the nation state. It also provides Chinese citizens with the experience of participating in Chinese modernity. Because of its double function, Alibaba plays a key role in connecting Chinese citizens’ experiences of digital participation to the digital imaginaries of a unified nation state.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Rockets, Smartphones and the Race for Technological Development

In December 2014, the Chinese spacecraft Chang’e landed on the moon and sent out its rover Yutu to roam the surface. Discussions of the Chinese lunar probe highlighted the modernist and technologist aspirations of the Chinese nation state. International reporting portrayed China’s technological achievement as part of an international competition. ‘Japanese media focus on the Chang’e: the best proof that China is now a space power’Footnote 1 the news platform China News proudly proclaimed (2013). Moreover, the New York Times called the moon landing a Chinese effort to ‘demonstrate that its technological mastery and scientific achievements can approach those of any global power’ (Wong and Chang 2011). Even though, as The Economist (2013) noted, Yutu was exploring the Moon’s surface more than forty years after the USA had sent a man to the moon, this success nevertheless made China the third nation, after Russia and the USA, to reach the moon. As these examples show, both Chinese and foreign newspapers discussed the moon landing as part of the larger history of national competition and technological development. Importantly, the event also suggested that China was in the process of ‘catching up’ with the West.

When the news of the moon landing broke, I was doing fieldwork in Beijing and could not help but notice how the event failed to excite my young and urban interlocutors. Of course, their (non)responses were not representative of China’s entire population (see de Kloet’s excellent chapter, this volume), but nonetheless it struck me as interesting that the topic of space exploration did not stir their excitement. Technological development has long played a crucial role in the quest for modernity in China, and my interlocutors were as excited about it as anybody. However, as members of the post-1980 generation, they cared more about mobile apps than rocket launches. They had grown up in China in which digital platforms provided them with new forms of consumption, communication and community. The innovations that drove the broader cultural and social changes in their lives were orchestrated by digital platforms. Of course, in part, the moon landing is a digital achievement. However, I would argue that it is not primarily seen as such. What I am considering here, therefore, is how digital platforms inform everyday experiences of digitality. In comparison, in failing to provide my interlocutors with participatory experiences, the moon landing seemed too far removed from their lives.

When I asked some of my interlocutors how they felt about the news, they bluntly told me that it didn’t interest them. The day after the moon landing I visited Bai Hang,Footnote 2 one of my interlocutors who accompanied me in my quest to buy some newspapers covering the moon landing. After we ventured out to buy the day’s papers, it quickly became evident that he had no idea where in the vicinity of his flat we could find such a thing. Like most of my informants, he got his news online. While online newspapers did report the moon landing, there was very little mention of it in my informants’ social media feeds, an absence made all the more significant by their exuberant enthusiasm for digital advances in China, be they ride-hailing apps, online payment systems or social media platforms in general.

A historical quest to modernize and thus strengthen the Chinese nation state reverberates through China’s project of space exploration. China’s moon landing continues a Cold War history of competing superpowers and thus gives expression to a technological and modernist Chinese nation state that is rapidly asserting itself as a global power. I do not mean to suggest that the moon landing did not generate a sense of excitement in China. Rather, I want to use the lack of interest among my own network of interlocutors as an opening to consider the following questions: How have digital platforms shaped their experience of national development? What makes explicitly digital visions of progress more appealing to them? And, how do digital platforms inform Chinese imaginaries of the nation state? Instead of expressing an interest in the new heights of Chinese space travel, my interlocutors, most of whom worked in the digital economy, raved about the supposed flattening effect of the Internet and spoke of grassroots entrepreneurship and the low entrepreneurial thresholds of China’s digital economy. These views echo governmental discourses on digitization that frame Chinese modernization as a participatory project.

In this chapter, I examine the production of such national visions as digital imaginaries—collective visions of a nation state rooted in the promise of digital technologies.Footnote 3 I argue that the power of such digital imaginaries of the nation state relies on everyday experiences of digital platforms as participatory. I also examine how digitality informs Chinese imaginaries of the nation state. Digital platforms, I argue, support the production of the nation state as a unitary space and inform visions of a participatory Chinese modernity at a time of growing socio-economic difference. The following discussion is divided into three parts. Part one considers the historical dimensions of digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state. Part two examines contemporary Chinese discourses about the digital as a decentralizing and flattening force that enables widespread participation. Here I draw on Anagnost (1997) to explore how such discourses enable the narrative production of the nation as a unitary subject. Finally, Part three turns to the question of how such digital imaginaries gain purchase. Here, I draw on Meyer’s work on ‘aesthetic formations’ (2009) to argue that digital imaginaries rely on everyday experiences of digital platforms as participatory environments.

Digital Imaginaries

Digital technologies have long played a central role in Chinese modernization efforts. Chinese digitization policies have rapidly and thoroughly transformed Chinese socio-economic landscapes. The speed of Chinese digitization was truly staggering. After the first email was sent overseas from China in 1997, as Christopher Hughes and Gudrun Wacker (2003: 1) observed in their seminal volume on digitization politics, the number of Chinese Internet users rose to thirty million in six years. In their introduction they concluded that Chinese politics could no longer be understood without examining ‘the social impact of information and communication technologies’ (ibid.). Since the publication of the edited volume in 2003, the number of Chinese Internet users has risen from 30 to more than 770 million (CNNIC 2018: 7). Importantly, the fast and far-reaching change to Chinese society was not a side-effect of digitization but its declared goal.

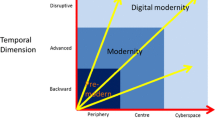

Hughes and Wacker called their volume China and the Internet: Politics of the Digital Leap Forward for two reasons. The first was to highlight a belief among Chinese politicians that information and communication technologies could allow China to ‘leapfrog’ stages of national development. The second was to emphasize the historical continuity of such efforts by hinting at MaoZedong’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ (1). Scholarship has continued to read China’s politics of digitization against the background of a historical effort to leapfrog development (Damm and Thomas 2006: 2, Damm 2007: 279–280, Liu 2011: 41–43). Apart from a historical desire to supercharge and rapidly speed up development generally, China’s strategic interest in digital development can be traced back to writers such as Alvin Toffler and his notion of the ‘Third Wave’ (Dai 2003: 8). The American futurologist’s work was well-received in China in the 1980s (Damm 2007: 279). Toffler, among other sources of influence, popularized the idea that so-called developing countries could leapfrog past the industrial stage of development to a third stage characterized by advanced informatization. Starting in the 1980s, Chinese efforts to modernize the nation state thus began to rely heavily on informatization.

Beijing’s Zhongguancun technology district, where I conducted research during thirteen months of fieldwork between 2013 and 2015, was the product of a digital developmentstrategy of this sort. It was also an example of the comparative dimensions of China’s nationalist project of modernization. Narratives of ‘catching up with the West’ discursively reinforce the unity of the nation state as a comparative unit. In addition, these narratives also reveal a global history of exchange spanning national boundaries. Zhongguancun, to borrow a concept from Peter van der Veer, is an example of an ‘interactional history’ (2001: 12) linking China and the United States, the outcome of a series of Chinese reimaginations and reproductions of Silicon Valley. The area acquired a strategic focus to emulate Silicon Valley-style technological entrepreneurship and, as such, highlights how imaginaries of the Chinese nation state emerged in the process of global exchange.

Having visited the United States shortly after the reform and opening-up policy of 1978, Chen Chunxian, a researcher and professor with the Chinese Academy of Science, returned convinced that Zhongguancun, with its high density of research institutes and universities, had the potential to become a similar environment for technological entrepreneurship (Tzeng 2010: 114). The area in Beijing’s north-west became an experimental zone for high technology in 1988 precisely because it was seen to share certain characteristics with Silicon Valley, most importantly its proximity to several institutions of higher education (ibid.). Thus, not unlike China’s moon landing, the existence of Beijing’s technology district is evidence of a desire to emulate what is perceived as ‘Western’ progress. It highlights a comparative nationalist project that is rooted in a teleological understanding of modernity, one in which ‘catching up’ is a prerequisite for national strength.

This drive to catch up with Western powers is an exercise in comparative nationalism. Like the moon landing, Chinese experiments in fostering a tech industry are set in a strongly expressed comparative national framework, in which development is framed as a national race for superiority. It exemplifies how ‘nationalism and the nation-state are not singular phenomena’, as van der Veer (2013: 660) has argued, ‘but emerged during a process of European expansion and the creation of a world-system of economies and states’. Within such an emerging world-system, China’s traumatic encounter with colonial powers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries created a desire to become a ‘modern’ nation state. The gap in development between China and Western colonial powers and ‘the specter of China’s exclusion’, as Lisa Rofel (1999: 8) phrases it, brought out a strong Chinese desire for modernization. This desire led to an at once highly comparative and competitive nationalism in which the ambition to catch up with foreign powers shaped Chinese modernist imaginaries and, ultimately, gave rise to projects of digital development.

This interactional history of technological entrepreneurship and its place in national strategies of digital development efforts were consequential. Even in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007 and 2008, China’s digital economy continued to boom. Domestic Internet companies and their digital platforms, it suddenly seemed, had not just caught up with the West but exceeded it. Giving voice to this notion, a New York Times headline read: ‘China, Not Silicon Valley, Is Cutting Edge in Mobile Tech’ (Mozur 2016). During my fieldwork, one event in particular appeared to confirm this view. In September 2014, the Alibaba Group entered the New York Stock Exchange. The outcome was sensational: Alibaba raised $25 billion, making it the highest initial public offering in history (Noble and Bullock 2014). Whereas China’s efforts in space travel were still a matter of drawing even with other global powers, the e-commerce giant’s success signalled that the country was already at the forefront of the world’s ‘digital revolution’. Sustaining hopeful visions of Chinese modernity at a time of economic slowdown, the digital economy, and digital technologies more generally, are at the heart of contemporary Chinese aspirations.

Digital Flattening

The digital economy is playing an increasingly central role in China’s effort to catch up and eventually overtake the ‘West’. As production numbers fell following the world financial crisis of 2007 and 2008, China’s booming digital economy became a key site of national ambition. Just as importantly, it became an important site of personal aspirations. As such, the digital economy supports a discourse of national development in which governmental and popular desires are aligned. The digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state employ an aesthetics of connectivity, access and participation. They draw on prevalent understandings of digital platforms as economically decentralizing and democratizing. In addition to censorship and online nationalist discourse, scholarship must consider how conceptions of the digital inform imaginaries of the nation state. Chinese discourse on the meaning of digital platforms is crucial to understanding their political significance. To this end, a closer look at China’s digital economy as a space of national imaginations is in order.

As techno-cultural formations, digital platforms make apparent this discourse of national strength and personal opportunity. Alibaba is a particularly clear example of this narrative of mutual benefit. Its success often appears an expression of China’s swift modernization and growing power. However, just before the Alibaba Group went on to claim the highest initial public offering (IPO) in history, CEO Jack Ma explained that it was the company’s mission to support ordinary Chinese that was guiding the development of Alibaba’s platform ecosystem (A Ke Si Jinrong 2014). Ahead of Alibaba’s listing, Jack Ma explained the company vision in a video. The clip, which I first encountered on a blog called ‘grassroots dream’Footnote 4 (2014), begins by explaining that the dream of Alibaba’s founders had been to support small businesses. ‘At Alibaba’, Ma asserts, ‘we fight for the little guy’ (2014). Towards the end of the clip, he proclaims that they are proud to ‘help entrepreneurs fulfill their dreams’ (2014). It is this overlap between the digital ambitions of the Chinese nation state and the personal aspirations of the individual that is crucial to understanding China’s digital politics. The trope of the digital platform allows the Chinese government to present digital development as a participatory project.

In 2013, China saw a boom in Internet entrepreneurship as growing numbers of entrepreneurs sought to create their own Internet start-ups and businesses. Picking up on this trend, the Chinese government introduced a ‘Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation’Footnote 5 (State Council 2015) policy aimed at incorporating the booming field of digital entrepreneurship into a national development strategy. One specific aim of the policy was to channel the efforts of early-stage or grassroots entrepreneurs into national innovation and growth. At the heart of this new policy was the notion that informatization had lowered the threshold for entrepreneurial endeavours benefiting China’s so-called masses (State Council 2015), making them an increasingly important resource in a project of national innovation. The national ambition expressed in this policy presents a very different narrative than that describing China’s space exploration. In this tale of digital development, Chinese citizens are not merely its spectators, as users, costumers and entrepreneurs they occupy a leading role in it.

The embrace of Internet users by the Chinese government is a limited one. The Chinese government has continuously sought to maintain control of its national online sphere. Online liberties are granted by the Chinese government, and the administrative and physical control of the Internet remains firmly in the government’s hands (Herold 2011: 1–2). While a firewall restricts access to a range of news and social media outside China, contentious keywords are blocked and ‘offending’ content quickly removed on the Chinese Internet. Much of this work of controlling online media is outsourced to online service providers who self-censor to avoid the anger of the government. These techniques and technologies of censorship are augmented by more subtle forms of control, in particular efforts aimed at ‘public opinion channeling’ (Gang and Bandurski 2010: 56). Of particular note in this regard is the employment of paid Internet commentators referred to as the ‘five cent army’ or wu mao dang (Shirk 2010: 14). While online debate definitely exists on the Chinese Internet (e.g. see Yang 2009, Yang and Calhoun 2008), these measures to control China’s online sphere highlight the government’s efforts to establish a tightly regulated national digital sphere.

The rise of the digital economy in China points to a governmental politics of limiting freedom of expression online while striving to create a more ‘open’ and ‘creative’ economic environment. In China’s digital economy, the creative potential of digital media—one heavily regulated, as the government tries to ban memes, censor social media and blacklist keywords—reappears as a source of economic development. Despite the apparent success of China’s digital economy, this vision of popular creativity highlights the government’s balancing act of encouraging innovation through digital media while censoring expression online. What must be noted here is how this approach politicizes the digital on two levels. In addition to the government targeting the content of digital media, it is the meaning of digital platforms itself that becomes a site of politics. Thus, along with the issues of censorship and the control of online media, it is necessary to explore what Brian Larkin has described as the ‘systemic efforts of governments to stabilize the symbolic logic of infrastructure’ (2008: 3). Digital platforms are not just politically significant because of how they are used—their perceived significance is a matter of politics.

An article posted as an explanatory policy discussion on the Chinese State Council’s official website cited Premier Li Keqiang as proclaiming: ‘We say that the world is becoming flatter; a very important reason for this is the birth of the Internet’Footnote 6 (Guangmingwang 2014). This narrative, which is also prevalent in Chinese start-up culture, articulates a promise that digitization will allow China’s population to participate and access opportunities. Li’s statement is significant as part of the government’s broader efforts to present the Internet as an equalizing force. Importantly, both the Chinese Government and start-up entrepreneurs discuss the Internet in terms of its ability to connect all grassroots entrepreneurs and thus flatten the social, cultural and economic landscape.

Alibaba and other big Chinese Internet companies are inspiring examples of success through the Internet, so are the life stories of their founders and CEOs. Perhaps like no other, Jack Ma embodies dreams of entrepreneurial success. His life and work are studied and discussed extensively. ‘Jack Ma is a feature article in the great story of the “China dream”’,Footnote 7Wang Chuantao (Wang 2014) argued in an online news article. For many of my informants, he embodied a truth about every entrepreneur’s digital potential for near unlimited success, however unlikely or difficult to achieve it may be. Jack Ma, the popular discourse maintains, had the right idea at the right moment in history, anticipating the potential of a Chinese digital economy, and was thus able to go from being a schoolteacher to becoming the founder and CEO of a multi-billion empire. His example charges the Internet’s flat topography with imagined potential, which is often framed as a connection between what is seen to be the flat, horizontal and distributed nature of the Internet on the one hand and visions of nearly unlimited entrepreneurial success on the other. This digital narrative, I argue, has become a crucial element in the production of the Chinese nation as a unitary space.

Digital Unification

In the Alibaba video clip discussed in the previous section, Jack Ma recounts the beginnings of Alibaba and his founding dream of building up a company to serve millions of small businesses. Today, he explains, this vision remains the same, as they continue their mission ‘to make it easy to do business anywhere’ (A Ke Si Jinrong 2014). During this last statement, the clip cuts from what looks like a clothing business led by women to a group of young men in sports clothes, huddled around smartphones on a hillside against the backdrop of a mountain range. Additional personal success stories feature a female art student in Shanghai who likes to shop on Alibaba’s Taobao platform and who proclaims that ‘Alibaba is a lifestyle’ (2014). Another scene shows a painter with a physical disability in a rural town in Sichuan province who found hope after selling her work on Taobao. ‘Without it’, she asks, ‘how would I sell my work in this little town?’ A Tibetan shop owner in Qinghai remembers how isolated he felt before Taobao. ‘A physical shop can only reach local customers’, he reflects, ‘but a Taobao shop is open to customers around the world’ (all quotes from A Ke Si Jinrong 2014).

Alibaba’s clip presents a China united by the company’s platform ecosystem. In it, class, gender and ethnicity do not appear to challenge the unity of the nation, nor does the rural-urban divide, despite being exacerbated by decades of marketization and economic reform. The idea that digitization will dissolve regional differences and inequalities is not entirely new. Beyond fuelling visions of international competitiveness, China’s digital development strategies have long held out a promise of temporal and spatial unity. The Chinese government, Karsten Giese has argued, believed that its informatization strategy could not only raise international competitiveness but also help overcome ‘interregional development gaps’ (2003: 30) in China itself. Alibaba’s video clip, although produced by a private corporation, resonates strongly with government accounts of national unity achieved through the digital. Its framing of Internet entrepreneurship as a unifying and universally accessible vehicle for success is closely aligned with government discourse around the same issue.

Mediations of digital entrepreneurship and consumption such as Alibaba’s clip present a particular mode of narrating the nation as a unitary subject. Of course, regional differences and inequalities of various kinds have existed and exist in China, despite growing numbers of Internet users. ‘The nation-space’, Anagnost has argued, ‘is never unitary but multiple within itself’ (Anagnost 1997: 4). The fact that the Internet has not simply brought an end to such multiplicity, but in some ways exacerbated it, was most evident when, following riots in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the Chinese central government cut the region’s access to the Internet between summer 2009 and May 2010 (Herold 2011: 2). More recently, accounts of the internment and digital surveillance of Uyghurs has shed light on how mobile technologies sustain a vast apparatus of control targeting China’s Muslim minority (Byler 2019). It is because of such ruptures and inequalities within the space of the nation, according to Anagnost, that nation states must continuously narrate and perform their own unity. The impossibility of such unity makes this an ongoing effort aimed at bridging temporal and spatial gaps.

Alibaba’s discourse about its own platform ecosystem, alongside government strategies of digital modernization, envisions a unified national space. Difference does not disappear in Alibaba’s video clip. Rather, the video presents a world in which digital platforms make regional, ethnic and class differences irrelevant. In it, the unification of national space stems from equal access to a capitalist and digitally mediated modernity. While many people in China will experience a reality that contrasts strongly with this audiovisual narrative, everyday experiences of connectivity and access do give some traction to promises of a digitally mediated and participatory Chinese modernity. This became evident to me during dinner with Bai Hang and his ex-girlfriend, Yu Ling, when the conversation turned to coffee. Yu Ling, who worked for an online company selling paintings and frames, had become interested in drinking good coffee ever since gaining access to a coffee machine at her workplace. When she asked me if I could recommend a good brand of coffee, the only one that came to my mind was one I had a habit of buying when I lived in Switzerland. I was convinced that it was not available in China and told her so. When she asked me to search for the brand’s name on her iPad Air, it turned out that the product, coffee beans roasted in Switzerland, was for sale on Taobao for 60 Yuan Renminbi.

My point is not to say that Bai Hang and Yu Ling completely accepted the notion of a digitally united nation. Rather, this episode supports the case about the participatory nature of Alibaba’s pioneering success in global modernity. As opposed to the moon landing, the company’s triumph on the New York Stock Exchange suggested that Chinese Internet users were already part of and contributing to a strong and modern China. If only through consumption, Alibaba made them part of a capitalist space of global modernity. If only for that moment, the gap between China and a perhaps loosely envisioned ‘Western modernity’ closed down. China caught up not through a symbolic technological achievement far removed from their lives, but in the mundane yet pleasurable moments readily afforded to them by digital platforms. ‘Not only does the nation mark its impossible unity in relation to time’, Anagnost has argued, ‘but also in space’ (Anagnost 1997: 4). The significance of Bai Hang and Yu Ling’s use of Taobao is that it affected how they experienced China both spatially and temporally.

The government’s efforts to stabilize the meaning of digital platforms draw on everyday experiences and seek to connect them to a national project. Its claims about the potential for national unity and strength through digitization gain purchase in relation to the everyday experiences of a global digital modernity. Alibaba’s narrative of a unified national space draws on a familiarity with its services that anyone in China who has used Taobao to shop for goods would have. Such consumption is an intimate part of people’s lives, a personal experience that provides a crucial foundation to claims that the Internet facilitates access, participation and connection across China. Experiences of the spaces and temporalities of global capitalist modernity on digital platforms like Alibaba’s Taobao inform understandings of the digital as a connective force. Such participatory experiences of technological development are a crucial experiential foundation on which digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state gain purchase. In the following section, I consider the relationship between experiences of the digital and digital imaginaries of the nation state.

Digital Experience

To understand the power of the digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state, I argue that scholarship needs to consider how corporeal experiences of digital platforms support the narrative production of the nation as a unified space. Benedict Anderson (2006: 37–46) famously pointed to the role of print capitalism and the creation of new spheres of communication as a central factor in the creation of ‘national consciousness’ and imagined communities. It is only a small step to extend his discussion to the Internet in China and ask how digital media support national imaginaries. However, as I have argued, a critical analysis has to move beyond an analysis of discourse to consider the corporeal experiences of digital platforms.

The digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state gain power in relation to bodily experiences of digital platforms. What makes this emphasis on the corporeal important is the question of how imaginaries find traction in people’s lives. To address this issue, I draw on Birgit Meyer’s (2009) critique of Anderson’s emphasis on imagination in the formation of communities. Her intervention seeks to shift our conceptual gaze from the mind, imagination and judgement to the senses, experience and the body. My discussion of digital platforms and national imaginaries similarly tries to highlight the crucial role of corporeal experience in sustaining national imaginations.

A consideration of the corporeal experiences enabled by digital platforms, I contend, is crucial to understanding how digital imaginaries of the nation state find traction in people’s lives. Meyer (2009: 3–5) argues that Anderson’s concept of the imagined community fails to consider sufficiently how communities materialize. For this purpose, she introduces the concept of ‘aesthetic formations’, through which (2009: 6) she hopes to shed light not only on the ‘modes though which imaginations materialize through media’, but also on how such materializations produce sensibilities ‘that vest these imaginations with a sense of truth’. By giving more room to materiality and sensation, Meyer hopes to broaden Anderson’s argument while holding on to his focus on media and mediation.

In previous sections, I have highlighted the important role played by discourses around digital platforms. Such discourses, however, must find purchase in people’s lives. How, then, does the discourse of the participatory and unifying potential of digital platforms become an experiential truth? Imaginations, Meyer argues, are invested and become matters of truth by becoming ‘tangible outside the realm of the mind, by creating a social environment that materializes through the structuring of space, architecture, ritual performance, and by inducing bodily sensations’ (ibid.: 5). Her argument is directed against ‘a representational stance that privileges the symbolic above other modes of experience, and tends to neglect the reality effect of cultural forms’ (ibid.: 6). Drawing on her discussion, I argue that corporeal experiences of digital platforms as participatory and unifying can invest digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state with a sense of truth.

This very truth of digitally mediated communities has been questioned in scholarship, which considers affective experience an insufficient basis for real communities. In online spaces such as blogs, social networks, twitter and video platforms, Jodi Dean (2013: 95) argues, affect is ‘a binding technique’ that is produced through reflexive communication: ‘Every little tweet or comment, every forwarded image or petition, accrues a tiny affective nugget, a little surplus enjoyment, a smidgen of attention that attaches to it, making it stand out from the larger flow before it blends back in’. Such affective links, however, she argues, do not result in ‘actual communities’ but ‘produce feelings of community’. Her argument appears to suggest that online communities aren’t quite real.

However, as with any other kind of community, what matters is that digital communities are experienced as true. Like national communities in general, digitally mediated communities, national or otherwise, become very ‘real’ when they are experienced as such. The more important question, therefore, is how digital platforms invest feelings of community with a sense of truth. Instead of questioning the actuality of China’s online community, I suggest, we should investigate how uses of digital platforms and the affective experiences they afford support the digital imaginaries of the nation. Crucially, this mediation draws on a digital aesthetics of access and participation. How China’s online community is experienced is therefore central to the production of digital imaginaries of the nation.

Beyond simply facilitating a national online sphere and a national digital economy, digitality can invest the imaginaries of a participatory Chinese modernity and a unified nation state with a sense of truth. Efforts to unify a wide range of experiences within the framework of the nation state seek to control the meaning and political significance of digital platforms. This stabilization of the meaning of the digital, however, takes place in relation to corporeal experiences, specifically in relation to experiences of digital platforms as participatory. Digital platforms provide a grammar through which a strong and unified China can be envisioned. They also afford the experiences in relation to which digital imaginaries gain purchase. Accordingly, the digital narration of the nation cannot be reduced to the imagination of a mind, but also needs to include bodily experience and the work performed on digital platforms, including online environments such as Taobao.

Digital experiences aren’t homogenous in China, and promises of digital participation and ultimately unification certainly won’t convince everyone. However, those who experience digital platforms as a positive force in their lives are more likely to find the promise of a participatory Chinese modernity and a unified nation state convincing. The widespread use of the Internet in China thus provides legitimacy to depictions of a nation that is spatially and temporally unified. To understand the power of digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state, scholarship must consider how digital platforms afford experiences of access and participation, as well as show how such experiences are in turn used by the Chinese government as evidence of a digitally flattened and unified national space.

Conclusion

In some ways, China’s moon landing and Alibaba’s platform ecosystem could not be more different. The moon landing is an extraordinary event and a relatively rare display of technological skill. Meanwhile, Alibaba’s platforms are used by Chinese citizens daily in countless routine transactions. However, what I have shown in this chapter is that, like the moon landing, digital platforms are important elements in a comparative and competitive nationalism that sees China as being in a global race for technological development. By beginning a discussion of the digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state with an anecdote of China’s moon landing, I have aimed to ask a question about the power of digital imaginaries.

I have argued that we must consider the participatory nature of the digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state. Like the moon landing, digital technologies inform narratives of national development that frame technological innovation as a global competition between nation states. As opposed to space technology, however, digital platforms are an intimate part of people’s lives. Like the politics of Mao Zedong’s ‘Great Leap Forward’, China’s ‘Digital Leap Forward’ claims to be a mass movement—not the sole achievement of an exclusive and remote research laboratory, but a collective achievement involving its over 700 million Internet users.

Chinese digital innovation strategies such as Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation speak to such participatory visions of national innovation and technological development. Ultimately, despite the persistence of profound divisions in China, imaginaries of digital unification fuel comparative and competitive nationalism in the country, for it is the vast number of Chinese Internet users that currently makes possible the size of its digital economy and the success of its digital platforms. It is also this collective of Internet users that fuels Chinese aspirations to become a digital superpower. In my research, it was this participatory dimension, however limited, that made the success of companies like Alibaba nationally significant.

My discussion of Alibaba has shown how the success of Chinese digital platforms echoes and reproduces imaginaries of the Chinese nation state in which users play a central role as actors in Chinese modernization. In such narratives, connectivity comes to signify the inclusion of China’s population as a whole. Alibaba’s narration of its platform ecosystem as a unifying technology is neatly aligned with a government discourse proclaiming digitization as a means to overcome the differences and divisions contained within the space of the nation. To challenge such digital imaginaries, it is important to consider the divisions and inequalities that continue to make up China’s digital politics. In some instances, digital experiences of access and participation may give validity to the government discourse of digital unification; in others, however, experiences of disenfranchisement, persecution and inequality will far outweigh them.

At the same time, stories of digital innovation as participatory cannot be reduced to governmental or corporate discourse in China. The Chinese government’s promise of digital development draws on a popular and widespread belief in the decentralizing and inclusive effect of digital technologies and incorporates them into its nationalist frameworks. It utilizes widespread enthusiasm for technologies that have often been perceived as the very source of new ideas and possibilities in recent decades. New online venues of exchange, participation and consumption have changed the spatial and temporal experiences of a large part of China’s population, providing digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state with a crucial experiential foundation. To assess the digital imaginaries of the Chinese nation state critically as involving a participatory modernity, we need to consider how government discourses draw on existing experiences and understandings of the digital as an equalizing force.

Notes

- 1.

Ri mei guanzhu chang’e luo yue: Zhongguo chengwei yuzhou daguo zui hao zhengming (this as well as all subsequent translations are the author’s).

- 2.

To protect my interlocutors’ anonymity, I use aliases.

- 3.

My discussion of digital imaginaries is indebted to Charles Taylor’s (2002) work on ‘social imaginaries’ and, more specifically, to Christopher Kelty’s (2008) exploration of open software as a kind of social imaginary. I use the concept of digital imaginaries to highlight the importance of digital technologies in shared imaginaries of Chinese modernity.

- 4.

Caogenmeng.

- 5.

Dazhong chuangye, wanzhong chuangxin.

- 6.

Women shuo shijie bian ping le, yige hen zhongyao de yuanyin jiu shi hulianwang de yansheng.

- 7.

Ma Yun shi ‘zhongguo meng’ hongda gushi zhong de yige texie.

References

A Ke Si Jinrong. 2014. Alibaba Shangshi Luyan Xuanchuan Pian Puguang Ma Yun Quan Yingwen Tuijie. A Ke Si Jinrong. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5NDQ3MTMyNA==&mid=202859391&idx=1&sn=96ef8b34204b8c02024e37449c387c90&scene=4#wechat_redirect.

Anagnost, Ann. 1997. National Past-Times: Narrative, Representation, and Power in Modern China. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. ed. London: Verso.

Byler, Darren. 2019. China’s Hi-tech War on Its Muslim Minority. The Guardian. Last Modified April 11, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/apr/11/china-hi-tech-war-on-muslim-minority-xinjiang-uighurs-surveillance-face-recognition.

CNNIC. 2018. The 41st Statistical Report on Internet Development in China.

Dai, Xiudian. 2003. ICTs in China’s Development Strategy. In China and the Internet: Politics of the Digital Leap Forward, ed. Christopher R. Hughes and Gudrun Wacker, 8–29. London: Routledge Curzon.

Damm, Jens. 2007. The Internet and the Fragmentation of Chinese Society. Critical Asian Studies 39 (2): 273–294.

Damm, Jens, and Simona Thomas. 2006. Introduction – Chinese Cyberspaces: Technological Changes and Political Effects. In Chinese Cyberspaces: Technological Changes and Political Effects, ed. Jens Damm and Simona Thomas, 1–10. London: Routledge.

Dean, Jodi. 2013. Blog Theory: Feedback and Capture in the Circuits of Drive. Polity.

Gang, Qian, and David Bandurski. 2010. China’s Emerging Public Sphere: The Impact of Media Commercialization, Professionalism, and the Internet in an Era of Transition. In Changing Media, Changing China, ed. Susan L. Shirk, 38–76. New York: Oxford University Press.

Giese, Karsten. 2003. Internet Growth and the Digital Divide: Implications for Spatial Development. In China and the Internet: Politics of the Digital Leap Forward, ed. Christopher R. Hughes and Gudrun Wacker, 30–57. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Guangmingwang. 2014. Yongbao hulianwang, yongbao yige yue lai yue ‘ping’ de shijie. Last Modified November 21, 2014. Accessed May 13, 2019. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2014-11/21/content_2781896.htm.

Herold, David Kurt. 2011. Noise, Spectacle, Politics: Carnival in Chinese Cyberspace. In Online Society in China: Creating, Celebrating, and Instrumentalising the Online Carnival, ed. David Kurt Herold and Peter Marolt, 1–19. New York: Routledge.

2013. Ri mei guanzhu chang’e luo yue: Zhongguo chengwei yuzhou daguo zui hao zhengming [日媒关注嫦娥落月: 中国成为宇宙大国最好证明-中新网. 中国新闻网]. Zhongguo Xinwenwang. Last Modified December 15, 2013. Accessed December 16, 2013. http://www.chinanews.com/gj/2013/12-15/5620231.shtml.

Hughes, Christopher R., and Gudrun Wacker. 2003. Introduction: China’s Digital Leap Forward. In China and the Internet: Politics of the Digital Leap Forward, ed. Christopher R. Hughes and Gudrun Wacker, 1–7. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Kelty, Christopher M. 2008. Two Bits. Duke University Press.

Larkin, Brian. 2008. Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Meyer, Birgit. 2009. From Imagined Communities to Aesthetic Formations: Religious Mediations, Sensational Forms, and Styles of Binding. In Aesthetic Formations: Media, Religion, and the Senses, 1–28. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mozur, Paul. 2016. China, Not Silicon Valley, Is Cutting Edge in Mobile Tech. The New York Times. Last Modified August 2, 2016. Accessed August 19, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/03/technology/china-mobile-tech-innovation-silicon-valley.html.

Noble, Josh, and Nicole Bullock. 2014. Alibaba IPO Hits Record $25bn. Financial Times. Last Modified September 22, 2014. Accessed July 20, 2016. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/0f97cc70-4208-11e4-a7b3-00144feabdc0.html#axzz4Evu8hDVm.

Rofel, Lisa. 1999. Other Modernities: Gendered Yearnings in China After Socialism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shirk, Susan L. 2010. Changing Media, Changing China. In Changing Media, Changing China, ed. Susan L. Shirk, 1–37. New York: Oxford University Press.

State Council. 2015. Guowuyuan Guanyu Dali Tuijin Dazhong Chuangye Wanzhong Chuangxin Ruogan Zhengce Cuoshi De Yijian: Guofa [2015] 32 Hao. State Council. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-06/16/content_9855.htm.

Taylor, Charles. 2002. Modern Social Imaginaries. Public Culture 14 (1): 91–124.

The Economist. 2013. China’s Lunar Programme: We Have Lift-Off. Last Modified December 16, 2013. Accessed December 16, 2013. http://www.economist.com/blogs/analects/2013/12/chinas-lunar-programme.

Tzeng, Cheng-Hua. 2010. Managing Innovation for Economic Development in Greater China: The Origins of Hsinchu and Zhongguancun. Technology in Society 32 (2): 110–121.

van der Veer, Peter. 2001. Imperial Encounters: Religion and Modernity in India and Britain. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 2013. Nationalism and Religion. In The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism, ed. John Breuilly, 655–671. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wang, Chuantao. 2014. Zhongguo bu hui zhi you yi ge Ma Yun. Zhongguo Qingnianwang. Accessed September 20, 2014. http://pinglun.youth.cn/ttst/201409/t20140920_5761256.htm.

Wong, Edward, and Kenneth Chang. 2011. China Unveils Ambitious Plan to Explore Space – NYTimes.com. Last Modified December 16, 2013. Accessed December 16, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/30/world/asia/china-unveils-ambitious-plan-to-explore-space.html?pagewanted=all.

Yang, Guobin. 2009. The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online. New York: Columbia University Press.

Yang, Guobin, and Craig Calhoun. 2008. Media, Power, and Protest in China: From the Cultural Revolution to the Internet. Harvard Asia Pacific Review 9 (2): 9–13.

光明网. 2014. 拥抱互联网, 拥抱一个越来越’平’的世界. Last Modified November 21, 2014. Accessed May 13, 2019. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2014-11/21/content_2781896.htm.

国务院. 2015. 国务院关于大力推进大众创业万众创新若干政策措施的意见: 国发 (2015) 32号. 国务院. Last Modified June 16, 2015. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-06/16/content_9855.htm.

王, 传涛. 2014. 中国不会只有一个马云. 中国青年网 Accessed September 20, 2014. http://pinglun.youth.cn/ttst/201409/t20140920_5761256.htm.

阿克斯金融. 2014. 阿里巴巴上市路演宣传片曝光 马云全英文推介. 阿克斯金融. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5NDQ3MTMyNA==&mid=202859391&idx=1&sn=96ef8b34204b8c02024e37449c387c90&scene=4#wechat_redirect.

Acknowledgements

For their helpful insights, I would like to thank all the participants of the conference ‘Religion and Nationalism’ held at Utrecht University in June 2019 for the fruitful discussion. I am indebted to Peter van der Veer for his guidance during my PhD studies and for providing me with an opportunity to research China’s digital politics. In addition, I want to extend my gratitude to Jarrett Zigon for providing me with an intellectual home at the University of Virginia in which to develop my argument.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lengen, S. (2022). Digital Imaginaries and the Chinese Nation State. In: Ahmad, I., Kang, J. (eds) The Nation Form in the Global Age. Global Diversities. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85580-2_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85580-2_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-85579-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-85580-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)