Abstract

Climate change is a most serious challenge. Committing the needed resources requires that a clear majority of citizens approves the appropriate policies, since committing resources necessarily involve a trade-off with other expenses. However, there are distinct groups of people who remain in denial about the realities of climatic change. This chapter presents a range of psychological and social phenomena that together explain the phenomena that lead to denial.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

3.1 The Scientific Consensus and Public Reception

There exists a scientific consensus that climate change is real, important, and anthropogenic. This was first shown by Oreskes (2004, 2018), and confirmed by later studies. Anderegg et al. (2010) found that 97% of the climate researchers most actively publishing in the field support the tenets of anthropogenic climate change, as outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Their latest report is IPCC, 2014; see also O’Neill et al., 2017).

Most people have come to recognize the fact and many do worry about it. A report by the Pew Research Center (Fagan & Huang, 2019) found that concerns about climate change rose significantly in many countries during the last decade. Majorities in most surveyed countries consider global climate change to be a major threat to their nation. In the US, close to 70% of people surveyed recognize that global warming is taking place, vs only 16% who think this is not the case. While US respondents tend to be less concerned about climate change, 59% still see it as a serious threat. A slim majority also understands that global warming is mostly human-caused (Leiserowitz et al., 2019). Moreover, about half of Americans (53%) know that scientists concur that global warming is happening. In France (IFOP, 2018), 67% of a representative survey agree that climate change is a problem mainly caused by human activity, but 24% think that it is not clear whether global warming is due to human activity or to solar radiation, while 6% thinks that global warming is not certain, and 3% consider that global warming is a hoax.

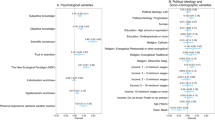

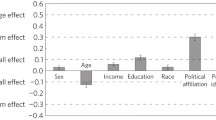

While there is now a “consensus on there being a consensus” amongst scientists about the reality of climate change, as Cook et al. (2018) put it, significant parts of the public are less certain about it. Several factors determine the extent of belief in climate change: motivational, cognitive (Rutjens et al., 2018) and socio-political. These factors, which we will discuss in turn in this chapter, interact with one another, and culminate in conspirational ideation. In a recent meta-analysis, Hornsey et al. (2016) observed that values, ideologies, worldviews and political orientation had more explanatory power about climate change beliefs than education, gender, subjective knowledge, and experience of extreme weather events.

3.2 Cognitive, Motivational and Social Determinants of Disbelief in Climate Change

It is often believed that reasoning consists of a set of cognitive processes—strategies for accessing, constructing, and evaluating beliefs – intended to reach a true conclusion. But motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990) is a powerful force, that thwarts this goal. An individual’s motivations affect their cognitive processes of reasoning and judgment. Rejection of science should be seen in this context: when its conclusions are unpalatable to an individual, they may resort to distortions of the normative reasoning processes (Lewandowsky et al., 2018; Lewandowsky & Oberauer, 2016).

Confirmation bias is one such cognitive and motivational distortion, which involves greater scrutiny and counter-argumentation of information contrary to one’s prior belief compared to information that supports it (Nickerson, 1998), along with greater motivation to confirm than to disconfirm one’s beliefs (Anderson et al., 1980). This can take the comparatively benign form of willful ignorance, as illustrated by an ethnographic study by Norgaard (2006) in a wealthy rural Norwegian community. Because Norwegian economic prosperity is tied to oil production in the North Sea, collectively ignoring climate change maintains Norwegians’ economic interests. Accordingly, many of them “don’t really want to know” about climate change and dismiss inconvenient facts (though this attitude did not deter the Norwegian government from imposing a carbon tax). The reliance on apparent disconfirmations of global warming, such as the local occurrence of unusual cold episodes, as was famously illustrated by Donald Trump would be another illustrationFootnote 1.

Motivated Reasoning

At least two determinants of motivated reasoning about climate change denial may be postulated. One is a general distrust of authorities, as we will discuss below, the other is cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957), defined as the motivation to decrease contradiction between two cognitive elements. In our case, as people dislike changing their habits about consumption, travels, food, etc. (Gardner & Rebar, 2019) climate change challenges our existing behaviors. This gives rise to cognitive dissonance, as a change in behaviors is required, leading to motivated reasoning to reduce the dissonance.

In addition to confirmation bias, information and misinformation have become readily accessible with the advent of the internet. This results in an increase of confirmation bias because internet’s algorithms confine people in echo chambers, which presents people with congenial information (Bronner, 2015; Pariser, 2011). Another consequence is the decrease in epistemic deference towards specialists (Anderegg et al., 2010; Kahan, 2012; Kahan et al., 2011a, b; Nichols, 2014). This socio-political factor is one of the reasons for the rise of conspiracy theories (Douglas et al., 2019). Trust in scientists and in science is decreasing. In the US, among Conservatives (but not Liberals) trust in science has been declining since the 1970s (Gauchat, 2012). Climate science has become particularly polarized, with Conservatives being more likely than Liberals to reject the notion that greenhouse gas emissions are warming the globe (Lewandowsky et al., 2013a). While the drop in the trust in science is more marked in the US than elsewhere (Hornsey et al., 2018), it may be found in other countries as well, (see the situation in France, IFOP representative survey, 2018).

Motivated reasoning can lead people holding strong views to question the credentials of specialists who hold views opposed to their own (Hart & Nisbet, 2012; Kahan et al., 2011a, b). For example, Kahan et al. (2011a, b) invented academic authorities whose made-up CV presented an impressive academic and occupational profile. Their study manipulated the views ascribed to those authorities on various controversial issues (such as climate change or gun control) in which they were supposedly top-notch specialist. It was found that when the views attributed to the specialists contradicted those of the respondent, their expertise was judged questionable. This explains why more information about there being a consensus about climate change does not necessarily increase belief about the consensus.

While for most people (Cook & Lewandowsky, 2016) such information results, as it should, in a stronger belief, the opposite was true for people for whom this information is very unwelcome. For the more extremely ideological people (as measured in the extent of their support for the free market economic model), more information about the scientific consensus weakened their belief in an existing consensus. Simply put, people are willing to trust real experts, but may reserve the right to identify real experts according to whether their views are congenial or not. In such cases, the competency of the experts is impugned.

3.3 Conspiratorial Thinking

To avoid accepting an unpalatable conclusion, some people may judge that the scientists who hold that view should be dismissed as untrustworthy. To them, if those scientists profess that view, it is not because they studied the evidence and reached the same conclusion according to the accepted canons of the scientific method. Rather, they profess that view because they are engaged in a secretive conspiracy (Diethelm & McKee, 2009).

This alternative (my opponent is either incompetent or a knave) sometimes leads climate science denialists to harass researchers critical of their views (Lewandowsky, 2019). Less dramatically, one of us debated about and ran endless supplemental statistical analyses during 1 week in an effort to argue with a denialist who was strenuously looking for errors in our data analysis (Wagner-Egger et al., 2018).

Distrust toward experts and official views as a product of confirmation bias is typical of “conspiracy theories” (CT), and indeed renders such beliefs resistant to disconfirmation: if anyone who argues against a belief is considered as being incompetent or a deliberate liar, that belief is effectively shielded by epistemic closure. (McHoskey, 1995) submitted equal-sized long texts to his participants, one endorsing the conspiracist explanation of J.F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, one in favor of the official version (lone gunner). The endorsement of the CT about Kennedy’s death was also measured for each participant, allowing to compare a group of believers and a group of nonbelievers in the CTs. Results showed that both believers and nonbelievers committed biased assimilation of the information given, and judged the information in line with their preexisting beliefs as more convincing than the rival information, and to an extent proportional to the extremeness of their preexisting attitude. But the CTs believers increased their belief in the CT after having read both texts, indicating a more potent confirmation bias among them.

As we mentioned above, CTs are related to distrust of political, judicial and journalistic authorities (e.g., Douglas et al., 2019). It is therefore unsurprising that the distrust is also directed toward science and experts. CTs have been observed about epidemics (e.g., AIDS, (Herek & Capitanio, 1994); swine flu, (Wagner-Egger et al., 2011); coronavirus pandemic (Oleksy et al., 2020), GMOs, vaccines, etc.. Some people are more prone than others to display this conspiratorial way of reasoning (Uscinski et al., 2017; Uscinski & Olivella, 2017), and belief in diverse CTs tends to correlate. Socio-political, psychological and cognitive factors have been found to correlate with (and sometimes cause) beliefs in CTs. Extreme political positions (and more at the right than at the left extreme), lower social status, minority belonging, paranoid and anxious feelings, and irrational beliefs (paranormal beliefs, intuitive thinking, cognitive biases, fake news sensitivity, etc.) are positively correlated with CTs adhesion in dozens of studies.

The Perception of Climate Science as a Conspiracy

Conspiracists beliefs predict a rejection of climate science. Lewandowski and colleagues (Lewandowsky et al., 2013a, b) observed in a sample of climate blog users and a representative US sample that conspiracist beliefs (for example that the FBI killed Martin Luther King, or that MI6 assassinated Princess Diana) were related to climate skepticism and other scientific realities (that HIV causes AIDS, smoking causes lung cancer; opposition to GMOs and to vaccines). This correlation is found in Europe too. In a IFOP representative survey in France in 2018, a significant correlation between CTs beliefs (about Apollo mission, chemtrails, etc.) and rejection of climate science has also been observed (IFOP, 2018). In another US representative sample, Uscinski & Olivella (2017) found that conspiracy thinking and political partisanship (political right) predicted climate denialism.

Other studies showed not only a correlational but also a causal link between CTs beliefs and climate change skepticism. (Van der Linden, 2015) randomly assigned participants to three experimental conditions, and had them watch a short video that presented either a climate change conspiracy video, or one that argued for the existence of climate change, or a neutral video on an unrelated topic. Following exposure to the climate conspiracy video, individuals updated their beliefs in line with the conspiracy information, making respondents less likely to believe in the existence of scientific consensus on human-induced climate change, and also less likely to sign a petition aimed at reducing global warming, compared to the other groups.

This association between conspiracist ideation and anti-science feelings may have serious negative social consequences in many domains. When holding CTs about epidemics or vaccines, people will display more risky behavior, such as not using condoms (Bogart & Bird, 2003; Bogart & Thorburn, 2005) or refusing to have their children vaccinated (Jolley & Douglas, 2014a). And of course, CTs about climate change decreases ecological intentions to reduce one’s carbon footprint (Jolley & Douglas, 2014b).

Sadly, scientists are not immune to motivated reasoning. This manifests itself in the prior attitude effect, where the perceived strength of novel information depends on the pre-existing belief. People who had the benefit of scientific training are in a better position to find facts that support their beliefs and reasons to reject whatever information is opposed to them. They can deploy a confirmation bias, and seek out information that confirms their prior belief, but are also adept at finding faults in research that would contradict their views. And indeed, individuals with greater science literacy and scientific training tend to have more polarized beliefs about controversial science topics (Drummond & Fischhoff, 2017). In particular, Kahan et al. observed that increased science literacy and numeracy led people to more polarized views about climate change (Braman et al., 2005; Kahan, 2012; Kahan et al., 2012; West et al., 2012).

3.4 Doubt and Uncertainty as a Political Strategy

Absent a proper understanding of complex issues, people often accept as true whatever is believed by people in their environment and presented to them by opinion leaders. In the US, belief in anthropogenic climate change has become a partisan issue, with conservatives being skeptical or dismissive about it, leading to more extensive rejection of the scientific consensus about climate change. The partisan gap is extensive, both about the reality of climate change (Fagan & Huang, 2019) and about the extent of the consensus amongst scientists about it, with conservatives underestimating it more than liberals (Cook & Lewandowsky, 2016). This gap is more marked in the US than in other countries (Chinn et al., 2020; Druckman & McGrath, 2019; Goldberg et al., 2020; Karakas & Mitra, 2020).

To understand the origin of this disparity, some historical background is needed. In the eighties, the fossil fuel industry correctly identified that the use of their products could lead to climate warming via the greenhouse effect (Banerjee et al., 2015). Energy companies set up several organizations, such as the Global Climate Coalition, the American Petroleum Institute and the Information Council for the Environment, to fund vast campaigns designed to influence public opinion. These campaigns lead to the polarization observed today (Dunlap & McCright, 2011).

The overall strategy consisted in promoting skepticism by conservative thinktanks funded by the fossil fuel industry (Hall, 2015). Skepticism is the operative term here. The campaign was not intended to convince people that there is no climate change, but to make them doubt, or in the famous phrase (Information Council for the Environment, 1991): “reposition global warming as theory, not fact.” That campaign was exposed in various publications (Climate Investigation Center, September 29, 2020).

Doubt and uncertainty were sufficient for their purpose, since near-certainty must be achieved to promote far-reaching economic and technological changes. Moreover, it is very difficult to argue against doubt. Controversy is usually taken as involving two opposing positions, amongst which people try to arbitrate by looking at the evidence. As we saw, people resist a change of opinion, using disconfirmation bias and selective search for information. That resistance will eventually break down in the face of overwhelming evidence, bringing about a conversion. But there is a third position, much harder to challenge, namely the agnostic one. Inasmuch as there is no pre-determined point where everyone must concede that something has been proven, people may reserve judgment indefinitely. The agnostic position is therefore more or less immune to the effect studied by Festinger, allowing its proponents to claim the mantle of fair, impartial and prudent judgment ad infinitum.

3.5 Conclusion

Climate change is a most serious challenge. Committing the needed resources requires that a clear majority of citizens approves the appropriate policies, since committing resources necessarily involve a trade-off with other expenses. This chapter presented a range of psychological and social phenomena that jointly explain the difficulty in meeting the challenge. Reasoning is often distorted by motivations, including the motivation to not be proven wrong. This can lead to a will to disqualify the scientific bearers of inconvenient truths. In its more extreme form, this tendency can develop into conspiratorial thinking, especially in a context of diminished trust in expertise and in political elites. Finally, these tendencies may be reinforced by vested interests, whose tactics on the issue of climate change has involved sowing uncertainty to produce political immobilism.

References

Anderegg, W. R. L., Prall, J. W., Harold, J., & Schneider, S. H. (2010). Expert credibility in climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(27), 12107–12109.

Anderson, C. A., Lepper, M. R., & Ross, L. (1980). Perseverance of social theories : The role of explanation in the persistence of discredited information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1037–1049. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077720

Banerjee, N., Song, L., & Hasemyer, D. (2015). Exxon: The road not taken. Retrieved from https://insideclimatenews.org/content/Exxon-The-Road-Not-Taken

Bogart, L. M., & Bird, S. T. (2003). Exploring the relationship of conspiracy beliefs about HIV/AIDS to sexual behaviors and attitudes among African-American adults. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95(11), 1057.

Bogart, L. M., & Thorburn, S. (2005). Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 38(2), 213–218.

Braman, D., Kahan, D., & Grimmelmann, J. (2005). Modeling facts, culture, and cognition in the gun debate. Social Justice Research, 18(3), 283–304.

Bronner, G. (2015). Belief and misbelief asymmetry on the internet. Wiley.

Chinn, S., Hart, P. S., & Soroka, S. (2020). Politicization and polarization in climate change news content, 1985-2017. Science Communication, 42(1), 112–129.

Climate Investigation Center. (2020, September 29). Climatefiles – Hard to find documents all in one place. Retrieved from www.climatefiles.com

Cook, J., & Lewandowsky, S. (2016). Rational irrationality: Modeling climate change belief polarization using Bayesian networks. Topics in Cognitive Science, 8(1), 160–179.

Cook, J., van der Linden, S., Maibach, E., & Lewandowsky, S. (2018). The consensus handbook.

Diethelm, P., & McKee, M. (2009). Denialism: What is it and how should scientists respond? The European Journal of Public Health, 19(1), 2–4.

Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S., & Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychology, 40(S1), 3–35.

Druckman, J. N., & McGrath, M. C. (2019). The evidence for motivated reasoning in climate change preference formation. Nature Climate Change, 9(2), 111–119.

Drummond, C., & Fischhoff, B. (2017). Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(36), 9587–9592.

Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2011). Organized climate change denial. In The Oxford handbook of climate change and society (Vol. 1, pp. 144–160). Oxford University Press.

Fagan, M., & Huang, C. (2019, April). A look at how people around the world view climate chang. Factank – News in the numbers. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/18/a-look-at-how-people-around-the-world-view-climate-change/

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford University Press.

Gardner, B., & Rebar, A. L. (2019). Habit formation and behavior change. In Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology. Oxford University Press.

Gauchat, G. (2012). Politicization of science in the public sphere: A study of public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. American Sociological Review, 77(2), 167–187.

Goldberg, M. H., Gustafson, A., Ballew, M. T., Rosenthal, S. A., & Leiserowitz, A. (2020). Identifying the most important predictors of support for climate policy in the United States. Behavioural Public Policy, 5, 1–23.

Hall, S. (2015). Exxon Knew about Climate Change almost 40 years ago. Scientific American, Online October 26, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/ Retrieved 19 June 2021.

Hart, P. S., & Nisbet, E. C. (2012). Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research, 39(6), 701–723.

Herek, G. M., & Capitanio, J. P. (1994). Conspiracies, contagion, and compassion: Trust and public reactions to AIDS. AIDS Education and Prevention, 6, 365–375.

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6, 622–626.

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., & Fielding, K. S. (2018). Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nature Clim Change, 8, 614–620.

Information Council for the Environment. (1991). Mission statement – Strategies; reposition warming as theory (Not Fact). In. American Meteorological Society Archives.

IFOP. (2018). Enquête sur le complotisme, ConspiracyWatch and Foundation Jean Jaurès. Available at: https://jean-jaures.org/sites/default/files/redac/commun/productions/2018/0108/115158_-_rapport_02.01.2017.pdf. Accessed 22 Aug 2019.

IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2014a). The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS One, 9(2), e89177.

Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2014b). The social consequences of conspiracism: Exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. British Journal of Psychology, 105(1), 35–56.

Kahan, D. M. (2012). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection: An experimental study. SSRN Electronic Journal, 8(4), 407–424.

Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H., & Braman, D. (2011a). Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. Journal of Risk Research, 14(2), 147–174.

Kahan, D. M., Wittlin, M., Peters, E., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L. L., Braman, D., & Mandel, G. N. (2011b). The tragedy of the risk-perception commons: culture conflict, rationality conflict, and climate change. Temple University legal studies research paper (2011–26).

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L. L., Braman, D., & Mandel, G. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 2(10), 732–735.

Karakas, L. D., & Mitra, D. (2020). Believers vs. deniers: Climate change and environmental policy polarization. European Journal of Political Economy, 65, 101948.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E. W., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., Bergquist, P., Ballew, M., … Gustafson, A. (2019). Climate change in the American mind: April 2019. Yale University and George Mason University. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Lewandowsky, S. (2019). In whose hands the future. In S. Lewandowsky & J. E. Uscinski (Eds.), Conspiracy theories and the people who believe them (pp. 149–177). Oxford University Press.

Lewandowsky, S., & Oberauer, K. (2016). Motivated rejection of science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(4), 217–222.

Lewandowsky, S., Gignac, G. E., & Oberauer, K. (2013a). The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science. PLoS One, 8(10), e75637.

Lewandowsky, S., Oberauer, K., & Gignac, G. E. (2013b). NASA faked the moon landing—Therefore,(climate) science is a hoax an anatomy of the motivated rejection of science. Psychological Science, 24(5), 622–633.

Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., & Lloyd, E. (2018). The ‘Alice in Wonderland’ mechanics of the rejection of (climate) science: Simulating coherence by conspiracism. Synthese, 195(1), 175–196.

McHoskey, J. W. (1995). Case closed? On the John F. Kennedy assassination: Biased assimilation of evidence and attitude polarization. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(3), 395–409.

Nichols, T. (2014). The death of expertise: The Campaign against established knowledge and why it matters. Retrieved from http://thefederalist.com/2014/01/17/the-death-of-expertise/

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises. Review of GeneralPsychology, 2(2), 175–220.

Norgaard, K. M. (2006). “We don’t really want to know” – Environmental justice and socially organized denial of global warming in Norway. Organization & Environment, 19(3), 347–370.

O’Neill, B. C., Oppenheimer, M., Warren, R., Hallegatte, S., Kopp, R. E., Pörtner, H. O., … Yohe, G. (2017). IPCC reasons for concern regarding climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 7(1), 28–37.

Oleksy, T., Wnuk, A., Maison, D., & Łyś, A. (2020). Content matters. Different predictors and social consequences of general and government-related conspiracy theories on COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110289.

Oreskes, N. (2004). Beyond the ivory tower. The scientific consensus on climate change. Science, 306(5702), 1686.

Oreskes, N. (2018). The scientific consensus on climate change: How do we know we’re not wrong? In Climate modelling (pp. 31–64). Springer.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin UK.

Rutjens, B. T., Heine, S. J., Sutton, R. M., & van Harreveld, F. (2018). Attitudes towards science. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 57, pp. 125–165). Elsevier.

Uscinski, J. E., & Olivella, S. (2017). The conditional effect of conspiracy thinking on attitudes toward climate change. Research & Politics, 4(4), 2053168017743105.

Uscinski, J. E., Douglas, K., & Lewandowsky, S. (2017). Climate change conspiracy theories. In Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science. Oxford University Press.

Van der Linden, S. (2015). The conspiracy-effect: Exposure to conspiracy theories (about global warming) decreases pro-social behavior and science acceptance. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 171–173.

Wagner-Egger, P., Bangerter, A., Gilles, I., Green, E., Rigaud, D., Krings, F., … Clémence, A. (2011). Lay perceptions of collectives at the outbreak of the H1N1 epidemic: Heroes, villains and victims. Public Understanding of Science, 20(4), 461–476.

Wagner-Egger, P., Delouvée, S., Gauvrit, N., & Dieguez, S. (2018). Creationism and conspiracism share a common teleological bias. Current Biology, 28(16), R867–R868.

West, R. F., Meserve, R. J., & Stanovich, K. E. (2012). Cognitive sophistication does not attenuate the bias blind spot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(3), 506.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Leiser, D., Wagner-Egger, P. (2022). Determinants of Belief – And Unbelief – In Climate Change. In: Siegmann, A. (eds) Climate of the Middle . SpringerBriefs in Climate Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85322-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85322-8_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-85321-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-85322-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)