Abstract

Promotion of “skilled birth attendants” (SBAs) in global maternal health policy has prompted a range of policy responses to “traditional birth attendants” (TBAs). In Indonesia the response has been to develop a national policy of partnership between SBAs (bidan) and TBAs (dukun bayi). This policy aims to ensure the presence of an SBA at every birth yet offers a role for TBAs. In this chapter I examine the development of a district regulation on partnership, promoted within the context of decentralization policies enacted in Indonesia from 1999. The district regulation aimed to strengthen the national policy in a location in West Java where TBAs remain popular. Drawing on 10 months of fieldwork from 2012 to 2013 at a district health office and on observations of its outreach programs, I elucidate how the regulation on partnership was promoted through the policy entrepreneurship of certain key figures in the district health office. They argued that the partnership regulation was the fastest means to improve maternal health. But casting a spotlight on the relationship between SBAs and TBAs diverted attention away from other health system challenges including under-resourced medical facilities and a weak referral system. Three contexts played into this process of bringing the partnership issue to the fore: global policies promoting SBAs and sidelining TBAs; pressure to achieve the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) on maternal mortality; and the limited financial power and decision space afforded to districts under decentralization in Indonesia. In this context, the regulation offered a viable path for demonstrating commitment to improving maternal health outcomes, yet one that failed to address broader constraints in the health system that contribute to persistent high maternal mortality rates.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Decentralization

- Indonesia

- Maternal health policy

- Partnership

- Skilled Birth Attendant

- Traditional Birth Attendant

Introduction

Promotion of “skilled birth attendants” (SBAs) in global maternal health policy raises the question of how policymakers should respond to lay midwives, termed “traditional birth attendants” (TBAs). TBAs are widely reported to be both popular and needed, especially in low-resource settings where licensed midwives may be unavailable (Rudrum, 2016; Niehof, 2014). Nevertheless, in many countries TBAs have been banned from attending births on the basis that their practices are dangerous (Rishworth et al., 2016; Guerra-Reyes, 2019). In marked contrast, Indonesia’s policy of partnership between licensed midwives, termed bidan, and lay midwives, termed dukun bayi, offers formal recognition of the dukun bayi’s role as a partner to the bidan. In this chapter I trace the development of a district regulation that gave legal force to the national partnership policy. I investigate how and why officials at LahanbesarFootnote 1 district health office in West Java prioritized the regulation on partnership between dukun bayi and bidan as an important means of addressing maternal death. How did Lahanbesar’s partnership regulation gain prominence within the local policy agenda despite multiple challenges to successful partnership including a weak enabling environmentFootnote 2 for skilled attendance, particularly, weak referral pathways and under-resourced obstetric care units in district hospitals (Agarwal et al., 2019; Makowiecka et al., 2008)?

My analysis draws on Shore and Wright’s (1997) elucidation of policymaking as a process of foreclosing alternatives. They define policy as sets of principles, rules, or guidelines that outline a course of action. Policies are prescriptive and normative and appear as technical instruments for improving efficiency and effectiveness. Yet the policymaking process is political and ideological. Problems are presented in ways that limit consideration of a broad range of options, such that one solution emerges as the obvious or only feasible option (Nichter, 2008). Similarly, the district regulation on partnership between bidan and dukun bayi was presented by certain district health officials as the fastest means to reduce maternal mortality. Attention was thereby diverted away from other ongoing approaches to reducing maternal mortality, such as improving the performance of health facilities and referral systems. Analysis of the policymaking process reveals how particular logics used by district policymakers foreclosed alternatives. These logics included framing the practices of the dukun bayi (known in West Java as paraji) as a key cause of maternal death and presenting the partnership regulation as the only means for addressing the paraji problem. I argue that the development of Lahanbesar’s district regulation on Partnership between bidan and paraji (dukun) was influenced by three larger policy contexts: the Millennium Development Goals that generated increased pressure to address maternal mortality (MDG 5); a global focus on skilled birth attendance as a means to achieve this goal; and the decentralization of health services in Indonesia from 1999 that increased accountability for maternal health outcomes at the district level.

Methodology

Site Selection

This chapter was part of a larger dissertation project examining health decentralization in Indonesia (Magrath, 2016). This included 10 months of research in 2012–2013 in Lahanbesar district, West Java; this place was selected because I had done research there for a World Bank project in 2000 and wished to track changes in health governance over time. Lahanbesar is located approximately midway between Indonesia’s capital city, Jakarta, and West Java’s provincial capital, Bandung. The main road linking these two cities passes through the northern part of Lahanbesar and factories located along the road provide wage employment, especially for women. The south of the district is relatively remote and poor with less access to wage employment.

Lahanbesar was originally selected due to high maternal and infant mortality statistics and the enduring popularity of TBAs known in the local Sundanese language as paraji. One of the largest districts in Indonesia, in 2012 it had a population of 2.3 million inhabiting 363 villages. There were three district government hospitals and several private hospitals and clinics, although specialists, including obstetrician gynecologists, rotated between hospitals/clinics and were not always available; 58 puskesmas (sub-district health centers providing outreach and clinical services by a doctor or nurse from 7 am to noon Monday to Saturday); and 3281 posyandu (neighborhood health posts organized by health volunteers, held monthly, attended by bidan and providing prenatal care, vaccinations, and growth monitoring). There were 628 bidan, the majority employed by government but many simultaneously running private practices (2.7/10,000 population compared with national average of 2/10,000 reported by Achadi et al. (2007)). There were over 2071 paraji (9/10,000 population). Many of the bidan have been working in the district for years or even decades, although bidan sent to remote villages tend to be the least experienced. Not all bidan speak the local language and they are frequently relocated. By contrast, paraji tend to remain in the same community for life.

Study sites were selected with the aim of tracing health policies from the district health office down to communities, and included the district health office, two health centers, and two villages, one village served by each health center. Eight additional health centers were visited while accompanying health personnel on monitoring visits.

Methods

Methods included participant observation; semi-structured interviews; focus group discussions; and document analysis conducted between June 2012 and April 2013. I carried out semi-structured interviews with key decision makers at the district office and staff at the health centers, and informal conversations with health volunteers, paraji and mothers (Table 8.1).

My key informants were the head of health services and one of her staff, both of whom had been village bidan, and the head of health promotion, PakFootnote 3 Yudi and two of his staff; the two case study health center heads; and two village bidan for the selected villages. Up to 12 interviews were conducted with each key informant over the course of the research.

Participant observation included over 100 days accompanying district health officials at their offices, on field trips and at 30 meetings and events; 30 days at case study health centers observing outpatient and obstetric services, interviewing staff, accompanying bidan, and attending 12 posyandu. I stayed in one village for 6 days accompanying and interviewing families and made frequent visits to families in the second village which was near my residence. Focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted with community groups, health volunteers and district office staff (Table 8.2).

I consulted statistical data, laws, policy documents, health promotion materials, and annual reports from the district health office, health centers, and village offices. I used Bahasa Indonesia, the official national language, spoken by most of my interlocutors. Occasionally Sundanese was used, and an Indonesian speaker translated for me. I took notes on a laptop and most interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded with permission. I used MAXQDA software for data analysis. The research was approved by the Indonesian Ministry for Research and Technology, RISTEK, and ethical clearance was obtained from University of Arizona IRB.

The Promotion of “Skilled Birth Attendants” in Global Health Policy

Promotion of “skilled birth attendants” (SBAs) has been a component of global maternal health policy at least since the safe motherhood initiative was launched in 1987. An SBA is defined as an “accredited health professional – such as a midwife, doctor or nurse – who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns” (WHO, 2004, p. 24). The policy focus on SBAs is based on statistical evidence suggesting that birth outcomes improve when SBAs are present (Freedman, 2003). The pivotal role of SBAs increased with the inclusion of the percent of births attended by SBAs as an indicator under Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 – “reducing by three quarters the maternal mortality ratio” (MMR) by 2000 (UNDP, 2003, p. 12).

The hidden text in the promotion of SBAs is the presence of lay midwives, known in public health discourse as Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs), who use systems of knowledge about pregnancy and birth that predate Western biomedicine and generally acquire skills through apprenticeship to another TBA. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines TBAs as “traditional, independent (of the health system), nonformally trained and community-based providers of care during pregnancy, childbirth and the post-natal period” (WHO, 2004, p. 8). However, anthropologists have documented great diversity in the social roles, training, and scope of practice of “traditional birth attendants” around the world (Pigg, 1997; Hay, 2015).

The expectation of global health policymakers is that SBAs will eventually replace TBAs (Hildebrand, 2017). Yet TBAs continue to assist women in the provision of maternity care, particularly in low-resource settings, where the essential inputs for quality maternity care, such as trained health workers, well-resourced health facilities, and a robust referral system, are often limited (Rudrum, 2016; Niehof, 2014; Rishworth et al., 2016). Even where SBAs are available TBAs remain popular due to the continuous and comprehensive care they often provide before, during, and after childbirth. This may include emotional support, religious and culturally important rituals, massage, and assistance with household chores. TBAs are often more easily available in remote and resource poor settings and their services are perceived to be more affordable (Hay, 2015; Titaley et al., 2010; Guerra-Reyes, 2019).

From the medical and policy perspective, the skills and services of TBAs are undervalued (Hildebrand, 2012; Bennett, 2017), and they are often blamed for high maternal and infant mortality ratios (MMR and IMR) due to perceived dangerous practices or the failure to refer emergency cases to medical services (Rishworth et al., 2016; Niehof, 2014). Global policies have shifted since the 1960s when the WHO encouraged training of TBAs in hygienic practices, identification of danger signs, and referral on the assumption that TBAs would often be the only person called to attend a birth. As the number of formally trained midwives has increased, new global guidelines discourage birth attendance by unsupervised TBAs since, even after training, they are not considered to be “skilled birth attendants.” Instead, health policymakers are encouraged to provide TBAs with roles that link them to SBAs and formal health services (WHO, 2004). Such roles include encouraging women to use biomedical antenatal, postnatal, and birthing services, and providing companionship, interpretation, massage, and drinks to women during and after childbirth. In some cases, TBAs are even allowed to manage uncomplicated births (Miller & Smith, 2017).

The overall effect of these policies has been to reduce the professional independence of TBAs. In many countries TBAs practices are regulated, with adverse consequences for their social status and for maternal health (Niehof, 2014; Rudrum, 2016; Rishworth et al., 2016; Guerra-Reyes, 2019). In Ghana, where there is a ban on TBAs practicing alone, they are torn between providing needed care and complying with the law. The shortage of SBAs results in some women giving birth by the roadside on the way to a distant health facility (Rishworth et al., 2016). In Peru, an inter-cultural birthing policy involves integrating “traditional” birthing practices through training SBAs in vertical birth. Yet TBAs (termed parteras) are excluded from this process and prohibited from attending home births (Guerra-Reyes, 2019). Given the ongoing role that TBAs play in maternity care, it is important to understand how policies relating to TBAs are developed at the local level and how they impact the care that TBAs are able to provide.

Maternal Health Policy in the Context of Decentralization in Indonesia

In Indonesia efforts to shift birthing practices away from use of TBAs, known in the Indonesian language as dukun bayi , predate contemporary global policy. The Dutch colonial government that introduced Western scientific medicine into Indonesia in the nineteenth century framed dukun bayi as dangerous to mothers’ health. They initiated trainings in hygienic practices that were continued after independence by Indonesia’s first two presidents Soekarno (1945–1967) and Suharto (1967–1998) (Stein, 2007). Suharto complemented training of dukun bayi with deployment of formally trained and licensed midwives, known as bidan. These bidan became part of the health workforce that was needed to manage an expanded public health infrastructure including district level hospitals, sub-district health centers (puskesmas), and village level monthly health posts (posyandu). The bidan program was rapidly expanded following the global conference on safe motherhood held in Kenya in 1987 that called attention to high MMR globally, including in Indonesia where it was estimated at 446 deaths per 100,000 births in 1990. Indonesia compared unfavorably with other nations in the region, for example, MMR was 152 in the Philippines, 79 in Malaysia, and 40 in Thailand (WHO et al., 2015). The high MMR in Indonesia was not only a health and humanitarian concern but also a source of national shame (Achmad, 1999).

The high proportion of mothers giving birth with dukun bayi, estimated at two thirds of births in 1991, was perceived to be a significant factor contributing to maternal mortality in Indonesia (Shiffman, 2003). In response, the bidan di desa (village midwife) program was launched in 1989 with financial assistance from the World Bank and UNICEF, with the goal that every village would have a resident bidan. Initially, nurses were given 1-year training in midwifery at a government or private university. In 1998 this was replaced by 3-year midwifery training for high school graduates (Heywood & Harahap, 2009). Indonesia’s bidan de desa program was part of a broader set of strategies to improve maternal health that included expansion of 24-h obstetric care facilities located at puskesmas and financial assistance to mothers giving birth through government health insurance programs. Jamkesmas, health insurance for the poor, initiated in 2008 was supplemented by Jampersal (2011–2014) that covered the cost of childbirth attended by a skilled birth attendant at a health facility (Magrath, 2016).Footnote 4 In combination, these policies contributed to substantial gains in maternal health. In 1990, 79% of births occurred at home, 65% of them with no skilled attendant (NPFPB & MoH, 1991). By 2017, 74% of births were delivered at health facilities and 91% of mothers used a skilled attendant (NPFPB & MoH, 2017). While Indonesia fell short of meeting its MDG 5 target, by 2015 maternal mortality had declined by 31% from 1990 levels to 305 deaths per 100,000 live births (Badan Pusat Statisk, 2015). Although these gains are considerable, national averages mask wide regional variation (Hay, 2015). Indonesia has 262 million inhabitants with more than 300 ethnic groups spread over 17,744 islands (Agustina et al., 2019).

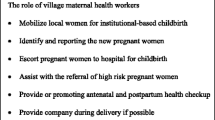

As the number of bidan increased over time, relationships between bidan and dukun bayi evolved. Initially, bidan were encouraged to train dukun bayi, thereby supporting their independent practices. Dukun bayi were provided with birthing kits including scissors, aluminum pans, and baby weighing scales (Hildebrand, 2012). By 2000, many villages had bidan and it became mandatory for every birth to be attended by an SBA. In line with WHO policy at the time, training programs for dukun bayi were phased out. Instead, they were encouraged to work as partners with bidan, under a national Policy on Partnership between bidan and dukun bayi that was formalized in 2007 (Titaley et al., 2010). Under the partnership dukun bayi are incorporated into the health system with a defined role that apparently reconciles the popularity of the dukun bayi with concerns over the safety of her practices. According to the implementation manual for Partnership between Bidan and Dukun Bayi (Indonesia Ministry of Health, n.d., p. 9–10), dukun are to encourage pregnant mothers to use ante-natal, birthing, and post-natal services of the bidan; accompany mothers to these services and assist the bidan ; carry out local religious or traditional rituals beneficial to health; educate mothers about pregnancy, danger signs, nutrition, birth planning, family planning, and breast feeding; and make home visits after the birth. Bidan are supposed to provide guidance to dukun and give them a share of their income from birth attendance (ibid p. 16). Although the manual describes the dukun as no less important than bidan (ibid p.6), the description of their roles is asymmetrical with dukun expected to give up independent practices to assist the bidan. This reinforces longstanding inequities in the social status and valuation of the two types of midwives from the perspective of the formal health system. Even though dukun bayi are highly regarded in their communities they are not always respected by bidan and other health professionals (Hildebrand, 2012).

Despite the clear and detailed guidelines, there has been wide variation in the implementation of the Policy on Partnership for Bidan and Dukun Bayi across Indonesia. Responsibility for implementing the policy falls on districts, according to decentralization laws, implemented in Indonesia from 1999. Decentralization, the devolution of authority from central to lower levels of government (Manor, 1999), offers increased scope for policy entrepreneurship as policymakers innovate in adapting national policies to fit local agendas (Pisani et al., 2016). This tends to increase regional variation in policy implementation and health outcomes (Agustina et al., 2019). For example, in Nusa Tenggara Barat (NTB) district officials have not enforced the partnership policy strictly. Bidan prefer not to partner with dukun arguing the policy is not applicable in their region. They claim mothers will be confused if they involve the dukun and they want to send a clear message that the bidan is best (Hildebrand & Magrath, 2016). In contrast, in West Java, the policy has been supported by provincial and district health officials. In Lahanbesar district, the government passed a district regulation in 2013 to strengthen partnership through provision of a budget to pay dukun bayi for each birth attended in partnership with bidan, and legally enforceable sanctions if they fail to partner.

The Development of the District Regulation on Partnership Between Bidan, Paraji, and Kader: Policy Entrepreneurship, the Use of Evidence, and the Role of Numbers

The key policy entrepreneur in the development of the district regulation on Partnership was Pak Yudi, a charismatic and ebullient individual, who was the head of Health Promotion, one of four departments in the District Health Office. His department was responsible for communicating health policy to the public, encouraging community participation in health policy and services, improving access to services through health insurance, and dealing with complaints from the public. Pak Yudi regarded regulation of paraji as one of the responsibilities of his department. He argued that many maternal and infant deaths occurred at the hands of paraji. While acknowledging that paraji were popular because they performed important cultural and spiritual roles, he maintained it was necessary to regulate their practices to ensure safer births. He argued the impact of the national policy on partnership was limited because it did not have legal force, hence the need to legalize the policy through a district regulation.

Over a period of 2 years from 2011 to 2013, Pak Yudi applied his entrepreneurial skills toward building support for his initiative. As head of Health Promotion, Pak Yudi had developed an extensive social network including NGOs, the media, businesspeople, and politicians. His office saw a steady stream of visitors and Pak Yudi used his connections to promote the regulation through a series of meetings and media engagements (see, for example, Ruslan, 2013).

In the following sections I provide ethnographic details of the policy-making process followed by Pak Yudi, focusing on three key components: building an evidence base, developing the text of the regulation, and presenting the regulation to key stakeholders from the district parliament. I highlight the ways evidence was used to narrow the options for accelerated efforts to address maternal death so that the regulation emerged as the best and most obvious solution.

Building the Evidence Base: Partnership Pilots and Paraji Perspectives

Pak Yudi gathered two sources of evidence to support his case for the partnership regulation: assessments of existing cases of legalization of the partnership policy; and research on paraji perspectives on the partnership policy. Two cases of legalization were examined, the first in Takalar District, South Sulawesi province, implemented in 2007 in nine sub-districts covering 83 villages. Reported births with bidan increased to 94% and maternal deaths fell from eight cases in 2007 to zero in 2009 and 2010. The second was a pilot within Lahanbesar district enforcing partnership in 23 villages in Cikakak sub-district in 2007 that had increased the percentage of births with bidan to 95%. During this second pilot paraji were paid Rp 50,000 (US$ 5) and kader were paid Rp 25,000 (US$ 2.5) for each birth attended in partnership.

The research with paraji was conducted by a member of Pak Yudi’s staff, BuFootnote 5 Irni, who invited paraji to participate in group interviews. Recordings from interviews conducted in three sub-districts give a consistent picture. The paraji all say that partnership with bidan is better than before because now the bidan takes the responsibility. According to one paraji “after birth, if there is heavy bleeding or the placenta hasn’t come out yet, I don’t have to worry.” Another stated she had taken five mothers to hospital, indicating her commitment to partnership.

In one interview two paraji were asked about the income they received. One paraji stated that she sometimes received Rp 20,000–30,000 (US$ 2–3) from the bidan, and about Rp 150,000 (US$ 15) from the mother. The bidan would say “here is something to buy soap,” thereby presenting it as a gift. According to Sundanese culture this made it easier to receive because it suggested a social rather than a purely economic transaction. The implication is that the partnership is an ongoing social relationship of care not motivated purely by economic gain. This distinction is reflected in the paraji’s explanation: “I wouldn’t want it to look as though I was profit seeking.” Hildebrand (2017) offers an extended analysis of how social relations of maternal care are understood as forms of gift giving by bidan, dukun bayi, and mothers in rural Indonesia. Asked if they knew mothers reluctant to give birth at the health center, one answered “many in the villages,” saying mothers feared their bodies would be exposed, contrary to Islamic guidelines on modesty (aurat). The second paraji quoted a mother saying, “I don’t want any fuss.”

Concerns with partnership did not emerge from these interviews, perhaps because paraji accepting an invitation to meet with district health officials were those who supported the partnership policy. Voicing criticism would have been unlikely since the power dynamic placed a district official in a superior social position to a paraji. Criticism is valued negatively in Sundanese culture, similar to Javanese culture (Berman, 1998).

Alternative Views on Partnership: Perspectives of Mothers, Paraji and Bidan

I elicited a wider range of views from interviews with paraji and mothers in their homes, in the absence of government officials. Three positions on partnership emerged: paraji who supported partnership, those who complied reluctantly, and those who avoided partnership. MakFootnote 6 Lestari’s views are similar to those of paraji interviewed by Bu Irni. She stated: “now it is better because there is no burden, the bidan takes the tension, it’s much better now.” Ma Halimah partnered reluctantly. She had worked with five different bidan, reflecting the high turnover for bidan. She preferred it before partnership when she could practice on her own. She explained: “If the baby comes quickly and I don’t report I am scolded.”

Mak Uma exemplifies the avoidance of partnership. She said “it was better before, now we have to go to the bidan, that’s the government recommendation. But I follow the mother, if she wants to go with the bidan, go ahead, if she wants to come with me, that’s fine too.” Mak Uma had attended to a mother 8 days previously. “I went to her house, she didn’t use a bidan, she said she didn’t want to. I took my kit and, there was no problem, I gave her massage three days after the birth, then seven days, I’ll continue up to 40 days.” Mak Uma did not understand why she was not supposed to practice independently. “I already finished my training, they gave me a plaque” she pointed to the sign outside her door stating she was practicing under the auspices of the district health office. She showed me the kit she had received in the 1990s, including scissors and aluminum pans. Although Mak Uma claimed she often worked with bidan, local bidan claimed she did not partner with them and that she discouraged mothers from using bidan.

Interviews with mothers who used the paraji’s services reveal how partnership works in practice. Three low-income mothers resided close to Mak Lestari who regularly partnered with the local bidan, Bidan Canti. One mother had given birth to her four children at home with only a paraji, in another village. She said, “it’s easier with the paraji, you just have to call one person, you don’t have to go anywhere.” Asked what advice she would give her 22-year-old daughter she responded, “if there is no problem, the paraji, but if it is a difficult birth then she would need to go to hospital.” She thought the paraji would refer her to hospital if necessary. The second mother always had difficult births and preferred “medis,” a medical birth. Two of her children were born with Mak Lestari in partnership with local bidan; the other two were born in the hospital due to complications. She explained that since Mak Lestari lived close to Bidan Canti, they always came together, whoever was called first. The third mother had her first two children with paraji in another village. She gave birth to her third child with Mak Lestari and Bidan Canti and was happy with the partnership.

Different stories emerged from Mak Uma’s clients. I met three mothers who had recently given birth with Mak Uma and two who were planning to, while attending a posyandu. One mother explained her baby was born at 2:00 am; they lived far from the road and the baby came fast. She had used a bidan during her pregnancy. Another mother stated, “with the bidan you will definitely be cut,” although Bidan Wawan, attending the posyandu explained cutting (episiotomy) was only done if necessary. One of the expectant mothers explained: “I’m afraid the baby will come too fast.” She feared engaging with the bidan anticipating that the bidan would emphasize the risks of childbirth. As Bidan Wawan explained, in Sundanese culture pregnant mothers should avoid hearing negative things.

What Makes for a Successful Partnership Between Bidan and Paraji?

These cases suggest that successful partnerships between bidan and paraji depend on the quality of relationships between mothers, paraji and bidan. With Mak Lestari and Bidan Canti’s good relationship, mothers follow partnership, but in the absence of such relationships, as with Mak Uma, mothers receive conflicting advice from the paraji and the bidan.

Bidan acknowledged that there are often tensions in relationships between bidan and paraji. Some expressed concern that legal enforcement of partnership could strain their relationships with paraji further, as paraji and mothers would become intimidated, fearing sanctions. One bidan related a case of “shock treatment” when a health center head had called the police to visit a paraji so that she would become afraid to practice alone.

A senior bidan thought bidan lacked communication skills needed to work effectively with paraji and mothers, while another confided that the quality of bidan training had declined due to the focus on rapid deployment. Furthermore, the least experienced bidan are deployed in remote areas where utilization of health services is low. I encountered this during a Jampersal (health insurance for childbirth) monitoring visit and it is also consistent with Makowiecka et al. (2008).

Bidan related additional concerns about the health system. They referred mothers to district hospitals not knowing whether there would be an obstetrician gynecologist, or necessary medical supplies. Sometimes they accompanied mothers to several hospitals with the risk of death due to delayed medical interventions increasing at each referral. Under-resourced hospitals also featured in mothers’ stories. One mother had delivered at the district hospital and noticed babies in the ICU unit sharing oxygen tubes. Subsequently she learned several of the infants died. The shortage of ICU units was confirmed by the Hospital Services Department head whom I subsequently interviewed. It was also said that health insurance was increasing demand on already inadequate resources. These concerns are consistent with the literature on maternal health in Indonesia that links high maternal mortality to weaknesses in the enabling environment for skilled attendance. Agarwal et al. (2019) refer to the low standard of emergency obstetric care in hospitals while Makowiecka et al. (2008) raise concerns over the quality of training and care provided by village bidan. Both emphasize inadequacies in referral systems.

My data reveal gaps between the assumptions of policymakers and the lived experiences of paraji, mothers, and bidan in relation to the partnership policy. When I presented my findings to Pak Yudi, he insisted that the regulation on partnership was the fastest way to address maternal death. Furthermore, paraji would benefit as they would no longer be blamed for poor birth outcomes and they would be paid whenever they partnered. Yet my conversations with paraji, mothers, and bidan revealed broader concerns relating to respect for paraji and professional support for bidan. These concerns prompt consideration of alternatives to legal enforcement of partnership, such as building more reciprocal partnerships based on mutual respect and trust and strengthening the enabling environment for skilled attendance through developing transportation and referral systemsFootnote 7 and increasing resources at health centers.

Reciprocal partnerships were envisaged in an AusAid (Australian) program implemented in 1995–1998 that advocated: “practices of partnership that are truly collaborative, and not hierarchical” (Hull et al., 1998, p. 36). A DfID–AusAID–MoH partnership initiative launched in several districts in 2007 included formal recognition, payment, and technical training for dukun bayi. Monthly meetings of dukun and bidan at puskesmas were used to strengthen partnerships (UNICEF, 2010). Bennett (2017) goes further, suggesting a two-way relationship, with bidan learning from dukun about patient-centered care. The national policy on partnership provides a framework for the development of such programs. Lahanbesar’s district regulation instead focuses on providing financial incentives and sanctions to encourage paraji to comply with the partnership policy. Less emphasis was placed on improving the quality of relationships through training of paraji or bidan.

Formulating the Text of the Regulation

The development of the text of the regulation represents another element in Pak Yudi’s strategy of policy promotion. He organized a series of meetings between district health staff and legal advisors, with participation from bidan and paraji. I attended some of these meetings and observed how the text of the national policy implementation manual was modified to accommodate the goals of the district regulation. Comparing the two documents, both share the objective of improving mothers’ access to quality midwifery services, encouraging dukun bayi/paraji to become partners to the bidan, and shifting mothers’ behaviors toward accessing services via partnership. The district regulation adds kader (health volunteers) into the partnership, reflecting the important role that they play as intermediaries between bidan, mothers, and paraji in West Java. Aside from this difference, the same definition of partnership is used in both documents:

Partnership between bidan, dukun bayi (and kader) in providing health services to women and children is a form of cooperation between bidan and dukun bayi that is mutually beneficial and based on principles of openness, equity and trust in an effort to ensure the safety of mothers and babies (Indonesia Ministry of Health, n.d., p. 4; Lahanbesar District, 2013, p. 5, author translation).

Both documents describe specific roles for bidan and paraji. Within the district regulation, the respective roles are detailed using the legal language of rights, duties, and sanctions (Lahanbesar District, 2013). The duties of the paraji include informing the bidan if a mother is pregnant or about to give birth, and encouraging the family to use the bidan’s ante-natal, birthing, and family planning services. Whereas the duties of the paraji are entirely framed in relation to the bidan, the term ‘paraji’ is not even mentioned among the duties of the bidan, suggesting an asymmetry in the partnership that is also reflected in the national policy. Sanctions specified in the regulation for both paraji and bidan include verbal or written warnings for failure to partner. In addition, the regulation provides a legal framework under which village officials may develop their own village laws, including additional sanctions such as fines for non-compliance. The district regulation was circulated within district government offices and went through several drafts before it was submitted to the district Parliament.

The District Parliamentary Meeting

Pak Yudi’s entrepreneurial efforts culminated in a meeting with parliamentary commissioners responsible for legislation on health, held on February 4, 2013 at which the case for the regulation on partnership was presented. The meeting was attended by six members of the parliamentary commission, several staff from the district health office, two bidan, and two paraji. Key speakers included Dr. Nia, head of the district health office, Pak Yudi, head of health promotion, and Bu Tia, head of the district bidan association. I detected three themes emerging from the speeches and ensuing discussions: first, the urgency of the problem of maternal death as mothers and infants should not be dying; second, the focus on paraji as a cause of maternal death, and third, the need for a partnership regulation as a mechanism for dealing with the problem of the paraji because the alternative, competition with the bidan, would not work. The sequential presentation of these three themes served to foreclose a broader discussion of the causes of and possible solutions to maternal death.

Theme 1: Mothers and Infants Should Not Be Dying

Dr. Nia stated that the purpose of the partnership regulation was to address the high infant and maternal mortality rate in the district. Whereas neonatal deaths had fallen from 551 in 2009 to 369 in 2012, maternal deaths had been rising from 33 in 2005 to 70 in 2011 and 77 in 2012. According to theory, Dr. Nia explained, maternal deaths should fall as births at health facilities rise, but in this district the reported incidence had risen, despite increased deployment of bidan and a rise in the proportion of births at facilities. One reason, she argued, was improved reporting, since it is bidan who report maternal deaths. Nevertheless, she emphasized further action was needed to address the high rates of maternal death.

Drawing on district-level administrative data, Dr. Nia then explained the causes of maternal deaths in the district, including bleeding, pre-eclampsia, and other sickness such as TB. She also discussed indirect causes such as inadequate health services and delays in accessing services, a veiled reference to the communities’ preference for home births with paraji. Dr. Nia stated dramatically that 25 of the 77 maternal deaths in 2012, or 32.47%, were associated with births attended by a paraji with no bidan present. She ended by presenting results of the partnership pilot carried out in Cicaklak sub-district of Lahanbesar district: “We implemented a trial, regulating partnership in 23 villages in 2007/8 and as a result 95% of births were attended by bidan and maternal deaths fell.”

Theme 2: Paraji Are of the Past, Not the Future

Following Dr. Nia’s speech, Pak Yudi, head of health promotion, commented that the main problem was that the public still choose the paraji over the bidan. The head of the bidan association took up this theme stating that although there were 628 members of her organization, the ratio of bidan to paraji was 1:5. “We have to clarify the limits of their work. We have to ensure that there won’t be additional numbers of paraji.” Here we have a new nuance. Not only are paraji presented as in need of regulation through a partnership that clarifies the limits of their work, the sheer numbers of paraji are presented as a threat that also needs to be contained. Partnership now appears as a temporary stage, as an ideal future with no paraji is anticipated.

Several members of the Commission defended the paraji, one stating “we don’t want to eliminate paraji as they have done in some areas. We need to protect the rights of both paraji and bidan.” Another argued paraji were community leaders who mobilized the public while a third added “they are people who are needed.” Yet despite this defense, they also acknowledged that individual paraji performed dangerous practices, suggesting a degree of ambiguity toward the paraji.

Although the commissioners’ plea to protect the rights of paraji could be interpreted as referring to their collective rights to exist as paraji, the response from the district health officials highlighted government programs offering the children of paraji the chance to train as bidan. According to Dr. Nia, 50 children of paraji had entered the program and had become government contract bidan earning a good salary. She explained the examinations and licensing required of bidan, a theme taken up by the head of health services, who added that bidan also receive on the job training. She added that paraji are invited to meetings, but many do not come. “There are difficult paraji and their arrogance leads to deaths at the hospital (from late referral).” In this way she presented bidan as governable in contrast with the paraji, some of whom appear ungovernable.

Theme 3: Competition Between Bidan and Paraji Will Not Work

Pak Yudi, head of health promotion, who had done most to bring the regulation into being, then argued that since paraji were more popular and more populous than bidan “we need partnership so that they don’t compete.” With a ratio of five paraji to every bidan “if they compete the bidan will not win.” This is an appealing argument in a cultural context where competition is seen as potentially destructive and is generally avoided in the interests of promoting harmony (Berman, 1998). Pak Yudi painted the roles of paraji and bidan as complementary with paraji providing cultural and spiritual roles and bidan providing medis, the medical role. But “paraji do not know how to sew tears after a birth, and some place money on the newly cut umbilical cord.” He added “in one month 7 infants died.”

This dramatic statement acted as a catalyst for the head of the commission who responded, with a conciliatory chuckle, saying “if there were 7 deaths in one month, why have we not done this earlier?” He agreed to push forward the regulation as fast as possible but added that guidance was needed for all parties and that the paraji should not lose their rights. The specific rights of paraji were not elaborated by the commissioners, however, in marked contrast to the well-defined rights for all parties outlined in the regulation. Shortly after the meeting, the regulation was passed and became effective mid-2013.

Discussion

the definition of alternatives is the supreme instrument of power (Schattschneider, 1960)

I left Indonesia just before the district regulation on Partnership between Bidan, Paraji, and Kader was passed in 2013, and was unable to monitor the impact of the regulation first hand. There have been no formal evaluations of the program to date, but informal WhatsApp conversations with several bidan suggest it did strengthen the partnership policy in Lahanbesar district, although payments to paraji dwindled once Pak Yudi was transferred to a different position. There have also been improvements in resource allocations to the district hospital, improving the enabling environment for bidan and paraji (Personal Communication, district hospital program manager 2019).

Despite the limitations of time, my account does shed light on the policymaking process that led to the passing of the district regulation on partnership. As predicted by Shore and Wright (1997) this involved foreclosing alternatives. During the process of building the evidence base and presenting arguments to law makers and other stakeholders, the regulation on partnership was presented not only as beneficial to all parties involved, but also as the fastest means to address maternal death. This diverted attention away from alternatives such as provision of more resources to health centers; improving referral systems; training bidan in communication skills; or deployment of more experienced bidan in remote areas.

Analysis of the presentations made during the parliamentary meeting illustrates how certain logics were used to present partnership as the optimal option for addressing maternal death. First, the problem of maternal death is given a sense of urgency through Dr. Nia’s presentation of the rising number of deaths from 33 in 2005 to 70 in 2011 and 77 in 2012. Although this dramatic increase may have been partly an effect of improved reporting, as Dr. Nia pointed out, it operated strategically to strengthen Dr. Nia’s message which was that according to theory, deaths of mothers and infants should be falling, not rising, given the increase in the number of bidan attended births. The unacceptably high numbers provided a moral injunction to act, paving the way for the second step in the logic, the framing of the paraji as the cause of unacceptably high numbers of maternal deaths. Reflecting global framings of SBAs as the solution to MMR this involves bracketing off shortcomings in the referral system and in the services provided by bidan and hospitals and instead shining the spotlight on incidents involving paraji, even though this represented only 32% of all cases of maternal death in 2012. Notably, the data provided did not allow for a comparison of the relative risks of birth with paraji and bidan. By omitting this information attention was focused on the paraji as the cause and therefore the obvious target for intervention.

The third step involved presenting legalization of the existing partnership between bidan and paraji as the only mechanism for dealing with paraji. The possibility of a more equal partnership encouraging bidan to learn from the skills and experience of the paraji as well as vice versa is not entertained. The paraji is included within the partnership to avoid a negative outcome – competition with the bidan – rather than because her services are valued by government. The logical steps used in these speeches are represented schematically in Fig. 8.1.

At play here is a manifestation of power described by Lukes (2005) as the capacity to evade conflict by omitting issues from the agenda. Tensions in the relationship between bidan and paraji were not acknowledged or addressed in the regulation. These tensions remain latent through health promotion messages that frame partnership as mutually beneficial and as fulfilling the rights of all parties involved (Magrath, 2019).

Three factors in the broader policy environment help explain why district health officials in Lahanbesar foregrounded the regulation of paraji. First, global policy on TBAs has evolved from recommending training of TBAs in the 1990s, to a sidelining of TBAs from the early 2000s, as SBAs have become more available. Discussions of global maternal health policy sometimes fail even to mention TBAs, despite their continuing presence and popularity in many parts of the world (for example, Agarwal et al., 2019). The expectation, voiced by Bu Ika in the parliamentary meeting, that paraji will soon disappear, is entirely consistent with the expectation of global policymakers at the time, although ideas of incorporation and partnership are re-emerging (Miller & Smith, 2017).

The Millennium Development Goals present a second factor in the global policy context that influenced the development of the partnership regulation. Percent births attended by SBAs is one of two key indicators for goal 5 to reduce maternal mortality, reflecting the prominent role given to skilled attendance as a solution to maternal death. Pressure to achieve the MDGs creates a domino effect at each level of the health system, and in the context of decentralization in Indonesia, particularly at the district level.

This brings us to the third factor, the national policy context of decentralization. Decentralization shifted lines of management and authority such that district officials are now more accountable to their district parliament and the public for health outcomes. Pak Yudi and his colleagues therefore needed to demonstrate competency in addressing the issue of maternal deaths. Their options for doing so were, however, limited by the amount of decision space actually granted to districts under decentralization in Indonesia (Heywood & Harahap, 2009; Trisnantoro, 2009). Decision space is defined as the capacity for officials at a given level of government to make decisions over a range of functions, including finance, administration, management, and policymaking (Bossert, 2014; Roman et al., 2017).

Some have argued that decentralization in Indonesia has been incomplete due to the limited decision space accorded to districts where central government has retained control over most forms of taxation (Fane, 2003). Thus, districts rely heavily on block grants from central government. Heywood and Harahap (2009) estimated that districts in Java rely on central government for up to 90% of their budget and that much of this is spent on salaries of permanent civil servants and programs mandated by central government, giving district health offices discretion over less than 25% of the budget. Whereas Pisani et al. (2016) refer to increased scope for policy entrepreneurship under decentralization in Indonesia, this is more evident in policy spheres such as health promotion that require limited funding. For districts in West Java with little discretion over spending of central government block grants, the capacity for innovative investments in infrastructure or human resources required to improve maternal health is limited. In this context, developing a regulation on partnership was a realistic option requiring a small amount of funding to compensate the paraji who joined the partnership.

Notes

- 1.

Lahanbesar is a pseudonym. All names and other personal identifiers in the chapter have been changed to protect privacy and confidentiality.

- 2.

The World Health Organization lists six building blocks of health systems that comprise the enabling environment: service delivery; health workforce; information; medical products, vaccines and technologies; financing; and leadership and governance. However, it is the interactions and coordination between these building blocks that is critical to ensuring adequate maternal health care, including effective referral systems, and comprehensive obstetric care at health facilities.

- 3.

Pak, short for Bapak (father), is a term of respect for older men.

- 4.

From 2014 Jampersal and Jamkesmas were integrated into the national health insurance program, Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional.

- 5.

Bu, short for Ibu (mother), is a term of respect for older women.

- 6.

Mak is a term of respect used for paraji.

- 7.

USAID funded Expanding Maternal and Neonatal Survival (EMAS) project initiated in 2011 aims to improve referral systems, but was not operational in Lahanbesar at the time of the research.

References

Achadi, E., Scott, S., Pambudi, E. S., Makowiecka, K., Marshall, T., Adisasmita, A., & Ronsmans, C. (2007). Midwifery provision and uptake of maternity care in Indonesia. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 12(12), 1490–1497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01957.x

Achmad, J. (1999). Hollow Development: The Politics of Health in Suharto’s Indonesia. PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Agarwal, K., Lilly, K., & Jeffry, S. (2019). Innovative approaches to enhancing maternal and newborn survival: Indonesia’s experience in an era of global commitments to reducing mortality. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 144, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12729

Agustina, R., Dartanto, T., Sitompul, R., Susiloretni, K. A., Suparmi, A., et al. (2019). Universal health coverage in Indonesia: Concept, progress, and challenges. The Lancet, 393(10166), 75–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31647-7

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2015). Indonesia – 2015 Intercensal Population Survey. Retrieved from https://microdata.bps.go.id/mikrodata/index.php/catalog/715/related_citations. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Bennett, L. R. (2017). Indigenous healing knowledge and infertility in Indonesia: Learning about cultural safety from Sasak midwives. Medical Anthropology: Cross Cultural Studies in Health and Illness, 36(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2016.1142990

Berman, L. (1998). Speaking through the silence: Narratives, social conventions, and power in Java. Oxford University Press.

Bossert, T. J. (2014). Decentralization of health systems: Challenges and global issues of the twenty-first century. In K. Regmi (Ed.), Decentralizing health services: A global perspective (pp. 199–207). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9071-5_12

Fane, G. (2003). Change and continuity in Indonesia’s new fiscal decentralization arrangements. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 39(1), 159–176.

Freedman, L. (2003). Strategic advocacy and maternal mortality: Moving targets and the Millennium Development Goals. Gender and Development, 11(1), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/741954259

Guerra-Reyes, L. (2019). Changing birth in the Andes: Culture policy and safe motherhood in Peru. Vanderbilt University Press.

Hay, M. C. (2015). Maternal mortality in Indonesia: Anthropological perspectives on why mother death defies simple solutions. In D. A. Schwartz (Ed.), Maternal mortality: Risk factors, anthropological perspectives, prevalence in developing countries and preventive strategies for pregnancy-related deaths (pp. 339–371). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Heywood, P., & Harahap, N. (2009). Human resources for health at the kabupaten level in Indonesia: The smoke and mirrors of decentralization. Human Resources for Health, 7(6). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-6

Hildebrand, V. M. (2012). Scissors as symbols: Disputed ownership of the tools of biomedical obstetrics in rural Indonesia. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 36(3), 557–570.

Hildebrand, V. M. (2017) Gift giving, reciprocity and exchange. In M. Ettorre, E. Annandale, V. M. Hildebrand, A. Porroche-Escudero, & B. K. Rothman (Eds.), Health, culture and society (pp. 179–211). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60786-3

Hildebrand, V. M. & Magrath, P. (2016). In policy’s shadow: Right to reproductive health in Indonesia. In Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Minneapolis, November 16–20.

Hull, T. H., Rusman, R., & Hayes, A. (1998). Village midwives and the improvement of maternal and infant health in NTT and NTB. Australian National University.

Indonesia Ministry of Health. (n.d.). Pedoman pelaksanaan kemitraan bidan dan dukun. Ministry of Health.

Lahanbesar District. (2013). Peraturan tentang kemitraan bidan, paraji dan kader kesehatan.

Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A radical view (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Magrath, P. (2016). Moral landscapes of health governance in West Java, Indonesia. PhD dissertation. University of Arizona.

Magrath, P. (2019). Right to health: A buzzword in health policy in Indonesia. Medical Anthropology: Cross Cultural Studies in Health and Illness, 38(6), 464–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2019.1604701

Makowiecka, K., Achadi, E., Izati, Y., & Ronsmans, C. (2008). Midwifery provision in two districts in Indonesia: How well are rural areas served? Health Policy and Planning, 23(1), 67–75.

Manor, J. (1999). The political economy of democratic decentralization. The World Bank.

Miller, T., & Smith, H. (2017). Establishing partnership with traditional birth attendants for improved maternal and newborn health: A review of factors influencing implementation. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(365). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1534-y

National Population and Family Planning Board (NPFPB) & Ministry of Health (MoH), Indonesia. (1991). Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey 1991. https://dhsprogram.com/what-we-do/survey/survey-display-35.cfm. Accessed 10 May 2020.

National Population and Family Planning Board (NPFPB) & Ministry of Health (MoH), Indonesia. (2017). Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey 2017. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr342-dhs-final-reports.cfm. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Nichter, M. (2008). Global health: Why cultural perception, social representations, and biopolitics matter. University of Arizona Press.

Niehof, A. (2014). Traditional birth attendants and the problem of maternal mortality in Indonesia. Pacific Affairs, 87(4), 693–715. https://doi.org/10.5509/2014874693

Pigg, S. L. (1997). Authority in translation: Finding, knowing, naming, and training “traditional birth attendants” in Nepal. In R. E. Davis-Floyd & C. F. Sargent (Eds.), Childbirth and authoritative knowledge: Cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 233–262). University of California Press.

Pisani, E., Kok, M. O., & Nugroho, K. (2016). Indonesia’s road to universal health coverage: A political journey. Health Policy and Planning, 32(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw120

Rishworth, A., Dixon, J., Luginaah, I., Mkandawire, P., & Tampah Prince, C. (2016). “I was on the way to the hospital but delivered in the bush”: Maternal health in Ghana’s Upper West Region in the context of a traditional birth attendants’ ban. Social Science and Medicine, 148, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.018

Roman, T. E., Cleary, S., & McIntyre, D. (2017). Exploring the functioning of decision space: A review of the available health systems literature. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6(7), 365–376.

Rudrum, S. (2016). Institutional ethnography research in global south settings: The role of texts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406916637088

Ruslan, H. (2013, March 17). Sukabumi gagas perda kemitraan bidan dan paraji. Republika. https://www.republika.co.id/berita/nasional/jawa-barat-nasional/13/03/17/mjtbzf-sukabumi-gagas-perda-kemitraan-bidan-dan-paraji

Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semisovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Shiffman, J. (2003). Generating political will for safe motherhood in Indonesia. Social Science and Medicine, 56(6), 1197–1207.

Shore, C., & Wright, S. (1997). Policy: A new field of anthropology. In C. Shore & S. Wright (Eds.), Anthropology of policy: Critical perspectives on governance and power (pp. 3–39). Routledge.

Stein, E. (2007). Midwives, Islamic morality and village biopower in post-Suharto Indonesia. Body & Society, 13(3), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X07082252.

Titaley, C. R., Hunter, C. L., Dibley, M. J., & Heywood, P. (2010). Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery? A qualitative study on delivery care services in West Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 10, 43–53.

Trisnantoro, L. (2009). Pelaksanaan desentralisasi kesehatan di Indonesia 2000–2007: Mengkaji pengalaman dan skenario masa depan (2nd ed.). BPFE-Yogyakarta.

UNICEF. (2010). Programme experiences in Indonesia: Documentation collection. https://www.medbox.org/document/programme-experiences-in-indonesia-documentation-collection#GO. Accessed 10 May 2020.

United Nations Development Program (NDP). (2003). Indicators for monitoring the Millennium Development Goals: Definitions, rationale, concepts and sources. United Nations https://www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/poverty-reduction/poverty-website/indicators-for-monitoring-the-mdgs/Indicators_for_Monitoring_the_MDGs.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb 2019.

WHO. (2004). Making pregnancy safer: The critical role of the skilled attendant: A joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. World Health Organization.

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, United Nations Population Division. (2015). Maternal mortality 1990–2015, Indonesia. World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Magrath, P. (2022). Regulating Midwives: Foreclosing Alternatives in the Policymaking Process in West Java, Indonesia. In: Wallace, L.J., MacDonald, M.E., Storeng, K.T. (eds) Anthropologies of Global Maternal and Reproductive Health. Global Maternal and Child Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84514-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84514-8_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-84513-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-84514-8

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)