Abstract

Patent laws and regulations in many countries have utilized the flexibility available under the WTO TRIPS Agreement to apply nationally appropriate standards to define the patentability criteria of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability, in order to ensure the grant of high-quality patents for genuine inventions. Robust search and examination are crucial for the application of this flexibility to ensure the grant of patents for genuine inventions, e.g., for secondary pharmaceutical patent applications which could lead to patent evergreening and adversely impact access to medicines by restraining generic competition. However, limited examination resources of patent offices have been stretched by the tremendous surge in the number of patent applications to be processed, leading to delays and backlogs. This has led patent offices to prioritize efficient and speedy processing of patent applications with their limited resources by using the search and examination work of other patent offices, sometimes to the extent of granting a patent on the basis of a corresponding grant by another patent office. This chapter discusses how work sharing has been driven by the major patent offices as part of a global patent harmonization agenda, both within the WIPO Patent Cooperation Treaty and through technical assistance and cooperation with other patent offices, and suggests how patent offices in developing countries could best harness the advantages of work sharing, particularly in a South-South cooperation framework, while safeguarding the ability to apply in practice the patentability requirements under their national laws through a robust search and examination of patent claims.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Patent examination is one of the most critical tools available to a country to ensure that patents are granted for genuine inventions that satisfy the patentability requirements under the law of a country. Patent examination practices adopted by a patent office plays a crucial role in the application of this important tool. Almost over the past four decades, patent offices all over the world have entered into collaborative relationships with each other that has effectively led to the creation of a global web of collaboration networks between patent offices. These networks have evolved in parallel to the pursuit of normative initiatives to harmonize substantive and procedural aspects of patent law in multilateral forums such as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) or in bilateral or regional trade agreements. While the normative patent harmonization agenda has been resisted, the administrative cooperation between patent offices has received relatively less attention. This chapter examines how the various kinds of cooperative work sharing arrangements that have evolved between patent offices can impact the ability of a patent office to conduct robust search and examination in accordance with their applicable national law and policy, and the opportunities and challenges that arise from the cooperation between patent offices.

2 Patent Examination: A Critical TRIPS Flexibility

Rigorous examination of patent applications to determine whether they satisfy the general patentability requirements of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability is the core function of patent offices in most countries. The decision by a patent office to grant patents should be based on as thorough an examination of the patent application as possible to ensure that only claims that fully meet the patentability requirements under the national law are allowed. An erroneously granted patent would remain valid unless it is successfully challenged before a judicial authority or a tribunal.Footnote 1 Thus, the patent offices are expected to act as gatekeepers of the patent system and ensure that patents of questionable validity are not granted.Footnote 2

Even while recognizing the possibility of grant of patents in all fields of technology as required under the TRIPS Agreement, countries can have different thresholds of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability in relation to specific fields of technology, such as pharmaceuticals. Thus, the outcome of a patent application can vary from one country to another, depending on the standard of patentability thresholds that are applied. The provisions of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) provide the flexibility to WTO members to apply rigorous standards of patent examination to ensure that only genuine inventions that meet high thresholds of patentability criteria are granted a patent.Footnote 3

Patent examination practices pursed by national or regional patent offices are often based on the application of legal fictions.Footnote 4 The adoption of some of these legal fictions by a patent office in its approach to the examination of a patent claim may be based on rules, regulations, bye-laws, guidelines or office practices. These may be also influenced by the adoption of treaty obligations for patent cooperation, technical assistance provided by influential patent offices, or administrative collaboration arrangements between patent offices based on memoranda of understanding (MOU) for such collaboration. Thus, even where the national law of a country lays down very strict requirements of patentability, its application can be significantly impacted by the practices followed by the patent office with regard to examination of patent applications.Footnote 5

This situation demonstrates the need for not only establishing appropriate thresholds of patentability under the patent law, but also the important role that patent examiners play in applying the law. Patent offices in developing countries face challenges that impact the rigorous application of the patentability thresholds. These challenges include limited human resources for patent examination, high examiner attrition rates, surge in the number of patent applications in different technical fields, backlogs of pending applications,Footnote 6 and meeting expectations to increase efficiency through expedited disposal of patent applications while ensuring the robustness of the patents granted.Footnote 7 Patent offices in developing countries are thus required to make policy choices that essentially entail trade-offs between these challenges. Depending on the policy choice that is prioritised, these could adversely impact the ability of the patent offices to meet the other challenges.Footnote 8 In the face of these conflicting policy priorities, patent offices often prioritise patent examination speed and use of limited human resources over ensuring the quality of granted patents.Footnote 9

Patent offices can respond to these challenges by increasing human resources for patent examination,Footnote 10 use of automation technologies or by leveraging the search and examination capacity of other national or regional patent offices. Of these, automation and reliance on the work products of other patent offices can also drive, and in turn thrive, under a globally harmonized patent system. Reliance on automation and outsourcing of search and examination work to other patent offices, depending on the nature and extent of the use of automation and outsourcing, can have an impact on the outcome of the patent examination in terms of the examination standards and practices applied. In the context of pharmaceutical patent applications, if such reliance leads to the application of lower patentability requirements that liberally allow the grant of secondary patent claims, it can have a detrimental impact on access to medicines.Footnote 11

3 Approaches to Patent Harmonisation

While patent laws are territorially limited in scope, the policy space for designing national patent law is circumscribed by the obligations of a State under applicable international IP treaties from the Paris ConventionFootnote 12 to the TRIPS Agreement, as well as additional obligations incurred under bilateral or regional free trade agreements. Certain IP treaties like the Patent Law Treaty (PLT) and the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) administered by WIPO also impose procedural obligations which must be followed by patent offices. These can apply to both the formality requirements in patent applications as well as to the timelines and other procedures to be followed. The scope of these treaties can also expand to shape the search and examination processes followed by national patent offices.

Besides the pursuit of a normative approach, collaboration between patent offices can also be used as a means of promoting harmonization. Such collaborations can be non-binding and persuasive in nature, in the form of technical assistance or work-sharing arrangements between patent offices. Patent office practices can acquire the force of a customary normFootnote 13 over a long period of time.

3.1 Normative Approaches

Much of the focus on patent harmonisation has been on norm-setting processes that aim to advance harmonisation of substantive aspects of patent law. Soon after the establishment of WIPO in 1967 developing countries unsuccessfully moved proposals to reform the Paris Convention. These attempts were countered through attempts by the WIPO secretariat to advance proposals for a complementary treaty to the Paris Convention, some of the provisions of which were eventually transposed into the TRIPS Agreement in the WTO.Footnote 14 Some of the other provisions of this draft treaty were reflected in the text of the PLT that was negotiated in WIPO after the adoption of the WTO TRIPS Agreement, as well as in the Substantive Patent Law Treaty (SPLT) which was unsuccessfully negotiated in the WIPO Standing Committee on the Law of Patents (SCP) till 2005.Footnote 15

The SPLT negotiations were part of an agenda being pursued in WIPO that regarded full and deep harmonisation of national laws relating to patentability as essential to the larger end “… to give national and regional patent authorities access to a common operational platform that permits them to cooperate, exchange information, share resources, and reduce duplication of their work.”Footnote 16 This initiative, known as the WIPO Patent Agenda, also suggested exploration of other mechanisms in addition to deep substantive harmonisation, including “… not repeating work done elsewhere …” to free up resources for the “… promotion of innovation, development of IP management skills, and other areas where active engagement may be required to realize the benefits of the patent system.”Footnote 17 Rationalisation of resource use, with a major emphasis on reducing duplication by fully or partially relying on the work done by other offices either through formal treaty arrangements or through informal cooperation, was suggested as a matter of critical importance for both patent offices as well as patent applicants.Footnote 18

This element of the WIPO patent agenda has continued to be pursued both within and outside of WIPO, even after the SPLT negotiations have been abandoned. Instead of treaty making, norm-setting on enabling reliance on the work of other patent offices is pursued through discussions on using soft law instruments such as amendment of the PCT Regulations and Administrative Instructions, or through the pursuit of exploratory discussions of patent office practices that draw from initiatives pursued in the form of cooperation between patent offices outside the framework of any WIPO treaty.

3.2 Persuasive Approaches

More than normative approaches, persuasive approaches have become the principal mode of promoting greater use of the work of other patent offices. The major mode of such persuasive approach has been the delivery of technical assistance and other forms of cooperation between patent offices, which have built confidence and reliance in the technical capacities, systems and work products of the patent offices from developed countries that provide such assistance and cooperation.Footnote 19 In some instances, patent offices that have received such assistance and cooperation have also agreed to fully recognise the patents granted by other patent offices without subjecting the same to further examination.Footnote 20

3.2.1 Technical Assistance

Technical assistance is a very critical feature of cooperation between patent offices. The United States Patents and Trademarks Office (USPTO), the Japanese Patent Office (JPO) and the European Patent Office (EPO)—collectively known as the Trilateral Offices—act as the “…global hub of co-operation and convergence in patent administration.”Footnote 21 Technical assistance to patent offices in developing countries has been a mode for the Trilateral Offices to introduce their technical systems for exchanging information and for search and examination of applications to the recipient offices. Indeed, such technical assistance has been delivered even before the adoption of the TRIPS Agreement.Footnote 22 The delivery of technical assistance to advance the economic interests of patent applicants from Europe still continues. The 2017 annual report of the EPO states that “Joint projects with our member states and patent offices from other regions are key to developing an efficient, quality-based international patent system. Tools and services developed by the EPO are often at the heart of these projects.”Footnote 23

One of the focus areas of cooperation for the EPO has been to enable recognition of European patents in foreign countries by concluding validation agreements with the EPO. The EPO has concluded validation agreements with the patent offices of Cambodia, Georgia, Moldova, Morocco, and Tunisia.Footnote 24 Pursuant to these validation agreements, a patent applicant may request that their patent applications filed or granted in the EPO be extended to these countries. Thus, where an applicant makes such a request to the EPO, the patent application filed in the EPO is recognised as a national patent application in the country with which a validation agreement has been concluded, and provisional protection is granted in that country. Subsequently, if the patent is granted in the EPO, it would have the same effect as a national patent in that country.Footnote 25 The validation requests in third countries can be made in respect of any application filed directly in the EPO as well as any international patent application filed under the PCT which subsequently entered the national phase in EPO region (European phase). The EPO is also negotiating similar validation agreements with some other countries and regional patent offices such as Brunei, Jordan, Lao PDR, the OAPI and Angola. According to the EPO, other countries in Asia have also “… signaled their interest in evaluating the possibility to enter into a validation agreement with the EPO.”Footnote 26

Countries concluding such validation agreements can, in effect, limit the flexibility that they have under the TRIPS Agreement to apply strict standards of patentability to limit or restrict frivolous patents on pharmaceutical productsFootnote 27 granted by patent offices like the EPO, that apply patentability standards that are very liberal and allow some of the claims that could be rejected under a strict approach.Footnote 28 It should be noted that the examination processes do not allow patent offices to reach “definitive judgments on patentability” of a claim,Footnote 29 but rather weigh the balance of probability of a claim being patentable, without necessarily being absolutely certain.Footnote 30 If overly broad secondary pharmaceutical patents receive validation outside the EPO pursuant to the validation agreements with EPO, such patents can have a negative impact on public health and access to medicines.

3.2.2 Quality of Patents

Cooperation arrangements between patent offices have been justified as a necessity in order to improve the quality of patents.Footnote 31 In this context, some national patent offices have focused on initiatives such as “… raising the threshold of inventive step, reducing the cost to examiners of rejecting an application, and reducing opportunities for applicants to manipulate the application process.”Footnote 32 However, at the multilateral level, the discussion on quality of patents has largely focused on enhancing “productive efficiency”Footnote 33 in the examination process of patent offices rather than on strengthening the thresholds of patentability criteria applied in the examination process.

In the WIPO SCP developed countries have advanced several proposals for developing a work programme on “quality of patents” focusing on enhancing examination resources of patent offices through technical infrastructure development, improvement of patent office administrative processes, and exploring how patent offices can cooperate and collaborate in conducting search and examination work in order to improve patent granting processes.Footnote 34 The proposals essentially focus on using information technology solutions to build search and examination capacity, exchange information on the quality of patent office processes based on feedback given to patent offices by applicants, and identify ways in which search and examination processes can be improved.Footnote 35 Pursuant to this, the SCP has exchanged information and shared experiences on work-sharing programmes among patent offices and use of external information for search and examination.Footnote 36

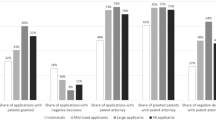

In 2016, the twenty-fourth session of the SCP agreed to undertake a survey on how WIPO member States understood “quality of patents” and implementation of cooperation and collaboration between patent offices on search and examination of patent applications. The most frequently mentioned cooperation arrangements in responses to the surveyFootnote 37 were the following: access to documents/databases/search systems of other offices; use of search and examination products from other offices; collaborative search and examination initiatives; carrying out search and examination for other offices; exchange of examiners with other patent offices; training on search and examination by other patent offices.

4 PCT Reforms

An important vehicle for promoting cooperation between patent offices all over the world is the PCT administered by WIPO. The PCT essentially allows the filing of an international patent application in the place of multiple national patent applications. The international patent application can designate countries where national phase entry of the application may be sought by the applicant after a preliminary review of the application (not an examination) by patent offices which are recognised as PCT International Search and Examination Authorities (International Authorities). This review is called the PCT international search and examination or the “international phase.”Footnote 38 In the international phase, all PCT applications go through a mandatory international prior art search with the applicants having an option to also seek an international preliminary examination report after the international search report is produced. Upon national phase entry, the patent application filed under PCT is treated as a national patent application and examined as such by the relevant national patent office. The reports produced during the international phase are available to the national offices for reference, but it is not binding on them to rely on those reports in making their decision on a patent application.

Though the reports produced in the PCT international phase are not binding upon national offices, this system also allows patent offices that produce the international search and examination report in their capacity as International Search and Examination Authority (ISEA) to influence the national examination of that application in a developing country.Footnote 39 As explained by the WIPO secretariat, one advantage of the PCT system is that “… the search and examination work of patent offices can be considerably reduced or virtually eliminated … (emphasis added).”Footnote 40

The accession of developing countries to the PCT has been made an obligation in various bilateral or regional free trade agreements.Footnote 41 However, while a large number of developing countries have acceded to the PCT, the system is predominantly used by applicants from a few countries.Footnote 42 Moreover, the international search and examination under the PCT system is conducted only by a few patent offices, and the majority of the international search and examination reports are produced by the EPO acting as an international search authority.Footnote 43 At the same time, many developing countries that have joined the PCT system lack capacity in conducting substantive examination, though they have witnessed significant increase in the number of patent applications filed in their countries through the PCT route.Footnote 44

Developed countries have consistently pursued the objective of eliminating the need for search and examination of patent applications in the national phase in WIPO discussions on reforming the PCT system.Footnote 45 The PCT system that was established in 1970 has been significantly transformed today through incremental reforms introduced through amendments to the Rules, Regulations and Administrative Instructions through which the PCT system operates.

Several proposals have been advanced by developed countries to discourage duplication of international phase work under the PCT system in the national phase, encourage collaborative search and examination or work sharing between patent offices, or enable national search and examination to be dispensed with at the option of a PCT Contracting Party. The US had submitted a proposal at the PCT Union Assembly of WIPO in 2000 for reform of the PCT in two stages—first, simplifying certain procedures and aligning the PCT with the PLT, followed by a comprehensive overhaul of the PCT system.Footnote 46 This proposal had received broad support from most developed countries.

The US proposal was transmitted to the PCT Union Assembly by the WIPO secretariat with a recommendation to establish a special body that should consider the proposal along with other possible proposals and report to the PCT Union Assembly.Footnote 47 The PCT Union Assembly established an ad hoc Committee on Reform of the PCT. The committee met in two sessions from 2001 to 2002 and discussed a number of proposals from WIPO member States and observers.Footnote 48

4.1 Working Group on PCT Reforms

The Working Group on Reform of the Patent Cooperation Treaty was established by the PCT Union AssemblyFootnote 49 pursuant to the recommendation of the ad hoc committee. In its first two sessions in 2001 and 2002, the working group discussed the issues that were identified for further examination by the committee. The WIPO secretariat prepared draft proposalsFootnote 50 based on the recommendations of the working group and submitted the same to the committee at its second session in 2001. These proposals were broadly focused on three issues: improved coordination of international search and international preliminary examination under the PCT and the time limit for national phase entry; the concept and operation of the designation system; and changes related to the PLT.

4.1.1 Establishment of a Written Opinion on Patentability to Accompany the International Search Report

On the recommendation of the committee, the PCT Union Assembly amended the PCT Regulations to the effect that a patent office could act as an International Search Authority or an International Preliminary Examination Authority under the PCT if it also held an appointment in the other capacity.Footnote 51 This amendment effectively allowed the same patent office to act as both the search and the examining authority in the international phase. This also enabled the expansion of the role of the International Search Authority through another amendment to the PCT Regulations to require them to issue in addition to the International Search Report—that would identify prior art documents in their order of relevance in relation to the claims made in the international patent application—a Written Opinion on whether the claims satisfy the patentability requirements in the light of the prior art revealed in the international search. This fundamentally changed the international search phase in the PCT to include a written opinion in the nature of a first examination report (FER) on the patent application. If an international preliminary examination under chapter II of the PCT was not requested by the applicant, the International Bureau of WIPO was required to prepare an International Preliminary Report on Patentability (IPRP) based on the Written Opinion of the International Search Authority (WOISA).Footnote 52 Thus, even if the applicant does not exercise the option of seeking an international preliminary examination following the international search report and publication of the application, national offices today receive not just a search report but also an IPRP on whether the application prima facie meets the patentability criteria. Deeper harmonisation of patent examination procedures was thus set in motion.

4.1.2 Automatic Designation of all PCT Contracting Parties for National Phase Entry

The PCT Union Assembly also approved amendments to the PCT RegulationsFootnote 53 to make the filing of a PCT application automatically applicable for national phase entry in all PCT Contracting Parties.Footnote 54 Thus, applicants are no longer required to designate national or regional patent offices for national phase entry and pay associated fees.

4.1.3 Establishment of an Optional Supplementary International Search

The committee recommended to continue future discussions on PCT reforms in the mode of the working group directly reporting to the PCT Union Assembly on the basis of the proposals submitted and future proposals. Several proposals relating to the reform of the PCT system were discussed in this working group in nine sessions held from 2001 to 2007.

The third session of the working group discussed the outstanding proposals relating to PCT reforms.Footnote 55 These included proposals relating to further improvement of the international search and examination system, for instance, to allow the applicants to opt for supplementary or top-up search.Footnote 56 The fourth session of the working group discussed an options paper on the future development of the international search and examination system, which suggested that the possibility of considering substantive revisions to the PCT for allowing search or examination by multiple authorities, introducing a supplementary search, a “top-up” search for new documents during the international examination, or even allowing a re-examination by the International Authority after national phase entry of the application.Footnote 57 It was also suggested that the international examination report could also indicate whether the application included subject matter on which there is variance in national laws concerning their patentability.Footnote 58 It was assumed that this would facilitate non-duplication of search and examination at the national phase on subject matter regarding which the application of the patentability criteria was relatively harmonized in practice. It is pertinent to note here that such harmonisation was being pursued by the Trilateral Offices through their technical assistance and cooperation programmes with national and regional patent Offices of several countries.

The WIPO secretariat suggested that States that did not have their own search and examination systems, or wished to reduce duplication of search and examination done by other offices, or to have a system for validation of patents in certain cases, could consider adoption of an optional protocol to register patents based on national phase entry accompanied by the international search and examination report, or allow the applicant to amend the application in case of a negative international examination report so as to enter the national phase with a positive report on patentability, or seek a re-examination at the international phase even after national phase entry.Footnote 59 The working group requested the WIPO Director-General to undertake consultations on these options.Footnote 60

At the sixth session of the working group, the WIPO secretariat submitted a proposal for amendments to certain rules under the PCT Regulations to allow the applicants to request for a supplementary international search by other International Search Authorities in order to obtain a more thorough search report, and also to request for an updated or “top-up” search during the international preliminary examination.Footnote 61 Following extended discussions over the next three sessions of the working group, consensus could not be reached. However, the 2007 PCT Union Assembly agreed to a proposal by FranceFootnote 62 and a related joint proposal by Japan and SpainFootnote 63 to amend the PCT Regulations to allow the applicants to make a request for a supplementary international search.Footnote 64

4.2 New PCT Working Group

The WIPO secretariat presented a report on the PCT reforms process to the 2007 PCT Union Assembly which noted that the working group had addressed all the issues on its agenda relating to the reform of the PCT and had reached agreement on amending the PCT Regulations on some of those issues.Footnote 65 However, it also noted that there would be an ongoing need for minor changes to the PCT Regulations in relation to certain proposals. It thus recommended the Assembly to formally declare the end of the mandate of the Committee on Reform of the PCT and the working group.Footnote 66 The Assembly agreed to a proposal by the WIPO secretariat to establish a new working group to do preparatory work on matters that would be considered by the Assembly in future.Footnote 67 This new working group—known as the PCT Working Group—has been meeting annually since 2008 with a broad mandate to discuss any matter which requires consideration of the PCT Union Assembly.

Discussions continued in the new PCT Working Group on promoting greater reliance on the International Search and Examination reports under the PCT system based on a preliminary discussion paper by the WIPO secretariat on enhancing the value of international search and preliminary examination under the PCT.Footnote 68 The discussion paper pointed to existing mechanisms within the PCT which can deliver similar benefits as work sharing mechanisms outside the PCT system, with the advantage of being more effective and being able to reach out to a larger audience. The paper raised certain questions for further consideration in order to improve the implementation or use of those mechanisms. The WIPO secretariat is of the view that any deficiency within the PCT system is primarily due to the way in which the system has been used sub-optimally by national offices, including International Authorities, and this could be addressed within the PCT system without engaging in any new PCT reform exercise.Footnote 69 At the request of the working group the WIPO secretariat produced another study on how to make the content of the international preliminary examination report more useful for the purpose of patentability assessment by national offices, and how to improve the international examination process itself.Footnote 70

The second session of the working group also discussed a number of other proposals aimed at deeper reform of the PCT. These included a roadmap proposed by the WIPO secretariat on the work that could be undertaken to facilitate a greater use of the PCT system by national patent offices, including International Authorities, with a focus on reduction or elimination of unnecessary duplication of search and examination work undertaken in the international phase when the application enters the national phase, greater use of work-sharing mechanisms developed outside the PCT system, and with the objective of ensuring high quality of granted patents while at the same time reducing the backlog of pending patent applications.Footnote 71 The working group also discussed other related proposals by the Republic of Korea for a three-track PCT systemFootnote 72 and a proposal by the US for comprehensive PCT reform.Footnote 73

The proposal by the WIPO secretariat on a roadmap for PCT reforms was discussed extensively through the session. The roadmap aimed to achieve a number of milestonesFootnote 74 which included reaching agreement on establishing a second written opinion prior to the issuance of a negative international examination report so as to allow the applicant the opportunity to amend the claims, including a “top-up” search in the international examination phase for prior art that may not have been available at the time of the international search done earlier, and establishing a third party observation system in the international phase.

Some developing countries were particularly concerned that the proposals in the roadmap as well as the related proposals on work sharing and comprehensive PCT reform effectively promoted harmonization of national patent examination practices, which could limit the ability of national Offices to undertake search and examination of patent applications entering the national phase through the PCT route.Footnote 75 The working group agreed to undertake further discussion on the proposals based on an assessment of the need for any change in the PCT system in the light of existing problems and challenges facing the system, while ensuring that the freedom of Contracting States to prescribe, interpret and apply substantive conditions of patentability, and without seeking substantive harmonization or harmonization of national search and examination procedures.Footnote 76

Thus, the third session of the PCT Working Group discussed a reportFootnote 77 by the WIPO secretariat analysing the functioning of the PCT system and the problems and challenges it faced. The Working Group endorsed the recommendations made in the report related to backlogs and improving the quality of granted patents,Footnote 78 timeliness in the international phase,Footnote 79 the quality of international search and preliminary examination,Footnote 80 incentives for applicants to effectively use the system,Footnote 81 skills and manpower shortages,Footnote 82 access to effective search systems,Footnote 83 cost and other accessibility issues,Footnote 84 consistency and availability of safeguards,Footnote 85 technical assistance, PCT information and technology transfer.Footnote 86 The Working Group also discussed a proposal by the WIPO secretariat for establishing a third-party observation system in the PCT and recommended that the WIPO secretariat should begin the development of such a systemFootnote 87 which has been operational since July 2012.

In the following sessions of the working group, some of PCT International Authorities reported on implementation of pilot projects between them on collaborative search and examinationFootnote 88 as well as integration of existing work sharing mechanisms outside the PCT system with the PCT. The PCT Regulations and Administrative instructions were also further amended to require International Preliminary Examination Authorities to conduct a mandatory “top-up” search for additional prior art that may not have been available at the time of conducting the international search.Footnote 89 Subsequent sessions of the PCT have continued to discuss proposals on work sharing within the PCT system and share experiences of work sharing arrangements between national offices as well as pilot projects within the PCT system.

5 Work Sharing Arrangements Between Patent Offices

Since the 1980s, the Trilateral Offices have entered into MOUs which have effectively made them “… the global hub of co-operation and convergence in patent administration.”Footnote 90 An integral part of this cooperation between the Trilateral Offices, which have been gradually extended to include other patent offices, has been the exploration of various work sharing arrangements relating to different aspects of the work of a patent office, involving two or more patent offices. The possibility of integration of such work sharing arrangements inside the PCT system is also being discussed in the PCT Working Group of WIPO. The WIPO SCP discussions on quality of patents have also focused on sharing experiences of such work sharing arrangements.

Work sharing arrangements have typically evolved through cooperation between patent offices over time through an incremental approach, led by the few major patent offices that process the bulk of the world’s patent applications. Such cooperation leverages the use of information and communications technologies (ICT) through digitization of patent documents, machine translation, electronic exchange of priority documents as well as search and examination reports. From mere exchange of information and reports, the work sharing arrangements can develop further to include greater cooperation wherein offices agree to make use, sometimes to the best possible extent, the work products of other offices. The emphasis, as discussed previously, is on increasing productive efficiency through speeding up the search and examination process.

5.1 Trilateral Cooperation

The EPO, JPO and the USPTO have implemented a number of work sharing arrangements between them under the Trilateral Cooperation that was launched in 1983 in order to deal with the dramatic increase in the number of patent application filings impacting the Trilateral Offices.Footnote 91 The initial area of cooperation was focused on digitization of all patent documents issued after 1920 and creating a common database of such documents. This was further expanded in subsequent years by the Trilateral Offices to develop a network for exchanging priority documents, an electronic exchange format for priority documents and a common patent application format.Footnote 92

Digitization, creation of technology specialized databases, and creation of a common ICT architecture facilitated electronic filing of applications and the conduct of paperless electronic search. However, the Trilateral Cooperation was not limited to facilitating exchange of documents. A number of comparative studies conducted by the Trilateral Offices on examination practices and the application of patentability criteria resulted in the harmonization of patent examination practices in various emerging technology fields, and also led to efforts to revise the PCT international search and examination guidelines.Footnote 93

The Trilateral Offices have also explored a number of projects for collaborative search and examination on a common patent application. In 2007 the USPTO and JPO launched a pilot project called “New Route” under which a national or regional patent application filed in either of the offices is deemed to be an application in the other office, and the search and examination results produced by the office of first filing can be used by the office of second filing in their own search and examination of the application. The applicant is also provided additional time, similar to that available under the PCT, to decide on whether to pursue the application in the other office, based on the search and examination results in the office of first filing.Footnote 94 The Trilateral Offices also agreed to undertake a pilot project known as the “Triway Pilot Programme” from 2008 to 2009, wherein all three offices agreed to conduct their own prior art search on a corresponding national application filed in all three offices and share the search results with each other in a timely manner.Footnote 95 In 2008, the Trilateral Offices also launched a pilot project on Strategic Handling of Applications for Rapid Examination (SHARE) under which each office agreed to give procedural priority to examining applications for which it is the office of first filing, with the understanding that the office of second filing would use the search and examination results of the office of first filing to the maximum extent practicable.Footnote 96

5.2 IP5 Cooperation

With the emergence of the patent offices of China (CNIPA) and South Korea (KIPO) among the leading patent offices in the world alongside the EPO, JPO and the USPTO, a similar framework of cooperation as among the Trilateral Offices has been established to include the CNIPA and KIPO.Footnote 97 This group is known as the IP5. The IP5 cooperation is particularly significant because almost 80% of the total patent applications in the world and almost 95% of the international patent applications under the PCT are processed by the IP5 offices.Footnote 98 The IP5 was launched in 2007 as a forum for cooperation among the leading five patent offices with a focus on “the elimination of unnecessary duplication of work among the offices, enhancement of patent examination efficiency and quality, and guarantee of the stability of patent right.”Footnote 99 In 2017, the IP5 expanded their vision to cooperate on “Patent harmonization of practices and procedures, enhanced work-sharing, high-quality and timely search and examination results, and seamless access to patent information to promote an efficient, cost-effective and user-friendly international patent landscape.”Footnote 100

It should be noted, as discussed in the previous section, that around the same time as the IP5 was launched, similar initiatives focused on promoting work sharing with a focus on elimination of “unnecessary duplication” was also being pursued in the WIPO discussions on PCT reforms. This means that when the proposals for reforms in the PCT international phase were advanced in the PCT working group discussions, the patent offices that handled almost the entire workload of the PCT international phase work were largely aligned to the proposed reforms. Reform of the PCT system is an integral part of the work of the IP5 which has also initiated a pilot project on collaborative search and examination of international applications under the PCT. The IP5 group’s perspectives and initiatives on quality management systems and work sharing arrangements are also discussed for possible integration in the PCT system.

One of the areas of cooperation among the IP5 offices is harmonization of patent classification systems among the IP5 offices as well as revision of the International Patent Classification (IPC) system administered by WIPO, to align the same to the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system of the IP5 and to introduce new classifications in fast moving emerging technology areas.Footnote 101 Such cooperation is also part of the Trilateral Cooperation discussed above.

Another major area of focus for the IP5 has been the “Global Dossier” project which seeks to offer, in a single portal, free and secure access to the dossier information on all applications in the same patent family that have been filed in the IP5 offices. The Global Dossier information has been expanded and linked with the WIPO Centralized Access to Search and Examination (CASE) system to include dossier information on patent applications under the same family filed in other patent offices outside the IP5 group.Footnote 102

Beyond the creation and expansion of systems to facilitate sharing of dossier information and conducting collaborative search and examination, the IP5 have also been exploring harmonisation of patent office practices within the IP5 in respect of patent application and grant procedures. It is possible that as the office practices are harmonised within the IP5, these could be extended through bilateral cooperation arrangements by the any of the IP5 offices to other patent offices across the world.

5.3 The Vancouver Group

In 2008, the IP offices of Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom (UK) formed a collaboration arrangement between them known as the Vancouver Group, with a similar focus as the IP5 and parallel discussions in WIPO on elimination of unnecessary duplication and ensuring more effective work sharing. Mutual exploitation of the work of each office with regard to patent search and examination has been a priority area of the collaboration between the Vancouver Group offices. Thus, the Vancouver Group has agreed on a set of principles on the basis of which mutual exploitation can be undertaken. These include relying on the grant of patent or the search and examination report of another Vancouver group office where possible, taking self-initiative for such work sharing without requiring the applicant to make a request, and utilizing the WIPO CASE system for the same.Footnote 103

5.4 PROSUR

PROSUR is a regional collaboration initiative launched in 2010 between IP offices of 13 Latin American countries.Footnote 104 The PROPSUR initiative seeks to enhance efficiency and quality in the search, examination and decision-making processes of the participating IP offices through the exchange of data and information systems. The primary focus of the PROSUR countries is on exchange of information and opinions on patent applications, which can be available as a reference for the other participating offices in the conduct of their own search and examination.Footnote 105 The information is shared among the PROSUR countries using ICT such as WIPO CASE and the electronic platform for collaborative examination (e-PEC) created by the patent offices of Argentina and Brazil.

5.5 ASPEC

In 2009 the nine member States of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) launched a regional patent work sharing programme called the ASEAN Patent Examination Cooperation (ASPEC).Footnote 106 Similar to PROSUR, ASPEC allows IP offices from ASEAN Member States to utilise search and examination results on a corresponding application in other ASEAN Member States. In 2019, applicants were also given the possibility of requesting utilizing the ASPEC mechanism to use international search and examination reports produced under the PCT in relation to a corresponding application by an International Authority within the ASPEC participating countries.

5.6 IP BRICS

The IP offices of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) launched a cooperation among the BRICS IP offices in 2012. In 2013 the IP BRICS agreed to a roadmap for cooperation.Footnote 107 The areas of cooperation agreed upon in this forum include exchange of IP office staff and examiner trainings, exchange of examination related patent information data and IP documentation exchange and sharing, and patent processes and procedures.Footnote 108 As part of this cooperation, annual meetings of the heads of the BRICS IP offices have been held since 2013, and 2 patent examiner trainings have been organized till date.Footnote 109 Studies to explore examination practices and procedures relating to specific kinds of patent claims, such as Markush claimsFootnote 110 relating to pharmaceutical patents, have also been proposed.Footnote 111

5.7 Patent Prosecution Highway

The Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) is the most extensive work sharing arrangement outside the PCT system. The PPH is a collaboration framework between participating patent offices in which an applicant receiving a positive determination on the patentability of a claim can make a request for accelerated examination of the corresponding claim in another participating patent office by using the search and examination results from the first office. According to the USPTO, an examiner will generally examine the application within 2–3 months of the PPH examination request being granted,Footnote 112 though there is no maximum time-period within which the examination should be done by the office conducting the accelerated processing. The processing time would obviously vary from one patent office to another relative to the number of applications they have to examine, with offices with a lower number of applications processing PPH accelerated search and examination faster than offices with higher number of applications.Footnote 113

The PPH began in 2006 as a pilot project between the USPTO and the JPO within the framework of the Trilateral Cooperation. Within a decade, the PPH has expanded to include a large number of national and regional patent offices, including from developing countries, into some form of a PPH agreement. The PPH agreements are in the nature of memorandum of understanding or collaboration agreements between patent offices and not legal treaties. Hence, implementation of the PPH mechanism does not require amendment of the national law and can be done merely through administrative regulations or bye laws that patent offices are allowed to adopt within the framework of the national patent law.

The PPH became a permanent mechanism between the USPTO and JPO at the end of the pilot period and was extended as a pilot project in 2008 between the USPTO and the EPO. In 2009, the EPO agreed to undertake a pilot PPH project with the JPO. Thus, the PPH was seeded and began to develop several shoots of bilateral PPH collaboration within the Trilateral Offices. The USPTOFootnote 114 and the JPO have also concluded several bilateral PPH agreements with other IP offices outside the Trilateral. In 2014, the pilot project on a PPH mechanism between the IP5 offices was launched by attempting leverage fast track patent examination procedures already in place at the IP5, marking further expansion of the PPH. Existing bilateral PPH arrangements that had been established between the offices within the Trilateral and the IP5 group were integrated under this IP5 PPH project.Footnote 115 In the same year, three offices from the IP5—JPO, KIPO and the USPTO—launched a “Global PPH” (GPPH) pilot project along with 23 other national and regional patent offices—Australia, Canada, UK (the Vancouver Group), Austria, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, New Zealand, Norway, the Nordic Patent Institute, Peru, Poland, Portugal, the Russian Federation, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, the Visegrad Patent Institute.Footnote 116 Both the IP5 PPH and the GPPH allow participating offices to use all the search and examination work products of the office of first filing or examination among the participating patent offices, including search and examination reports and written opinions produced by them as International Authorities under the PCT. In parallel with these initiatives, more countries are increasingly being brought within the ambit of the PPH through bilateral PPH agreements. Currently, more than 50 national or regional patent offices are part of the PPH network through a slew of bilateral or global PPH agreements.

Even where a patent office is a party to the PPH network through some form of PPH agreement, the extent to which offices use the PPH system can vary, with some offices using the PPH more widely than others. For example, under bilateral PPH agreements, the PPH route is only available to the patent applicants from the respective parties, and there can be a maximum limit on the number of applicants who can make use of this route. The PPH agreement could be limited to certain specific technology sectors while excluding other sectors with sensitive public interest concerns, such as pharmaceuticals.Footnote 117 However, like most work sharing schemes, the PPH has also expanded through a gradual and incremental approach. Therefore, the extension of existing PPH arrangements that are limited to specific technology sectors could be extended to incrementally include processing of patent applications in other technology sectors.

6 Opportunities and Challenges

Patent cooperation and work sharing between patent offices presents both opportunities and challenges for patent offices. For resource constrained national patent offices, work sharing can be an attractive mechanism to ensure timely processing of patent applications. Use of ICT, digitization, automation, machine translation, etc. have made work sharing an attractive and realistic proposition. At the same time, work sharing could present the risk of trade-offs being made by patent offices in favour of efficient, accelerated and timely completion of search and examination work, over ensuring robustness of the search and examination itself. The risk of such trade-off is much more where work sharing arrangements apply to fields of technology, such as pharmaceuticals, where there can be significant variance between the patentability thresholds under the applicable national law.

6.1 South-South Cooperation

While a number of patent offices in developing countries have bilateral MOUs on cooperation with patent offices in developed countries, cooperation between patent offices of developing countries has been very limited. Exploring work sharing or collaboration between patent offices among developing countries on the basis of South-South cooperation could be explored further. Work sharing arrangements like PROSUR and ASPEC enable patent offices in Latin America and the ASEAN to utilise their search and examination results on corresponding patent applications in their respective offices. Beyond formal work sharing agreements, patent offices in developing countries could also cooperate to undertake examiner exchange programmes, sharing of sector specific guidelines on patent examination, sharing of search and examination reports, objections or questions raised in first examination reports (FER), results of pre-grant opposition proceedings, and information on post-grant revocation or grant of any compulsory license on a patent. For instance, initiatives similar to the project proposed by INPI of Brazil under the IP BRICS cooperation to undertake a study on examination procedures on patent applications containing Markush formulas with the objective of standardizing examination guidelines relating to such claims, could be further explored by other developing country patent offices and also be extended to include other forms of secondary patent claims made in the pharmaceutical sector.

It is critical that patent offices in developing countries engage in cooperation among them within a South-South framework not only in form but also in terms of policy orientation. The focus of South-South patent cooperation should be on harnessing the resources of their national and regional patent offices to ensure that those resources could be deployed efficiently to ensure robust examination of patent applications. To persuade the patent offices to collaborate with this orientation, it would be necessary to utilise existing forums of South-South cooperation such as IBSA,Footnote 118 MERCOSUR,Footnote 119 UNASUR, the regional economic communities (REC) in Africa,Footnote 120 as well as regional cooperation forums in Asia to provide guidance to the respective national and regional patent offices of their member States, to cooperate in pursuit of this objective.

A priority area of focus in this regard should be on the examination of pharmaceutical patent applications with the objective of enabling patent offices to fully utilise the flexibilities available under the TRIPS Agreement with regard to the differential application of the patentability criteria of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability by taking into account the specificities of the technological sector. Thus, patent offices from developing countries can collaborate to share experience and knowledge and develop tools such as patent examination guidelines to enable the conduct of search and examination of pharmaceutical patent applications by applying rigorous standards. Objections or clarificatory questions raised in FERs by applying such rigorous standards could be shared through appropriate ICT tools with other patent offices for their reference. Other offices could consider whether similar questions could be raised in the context of the requirements under their national law or regulations. High quality FER objections can result in the withdrawal or abandonment of frivolous applications.

6.2 Safeguarding and Utilising TRIPS Flexibilities

While South-South cooperation could be explored in the area of patent search and examination as a means of strengthening the implementation of robust patent examination standards, a critical challenge for patent offices from developing countries in respect of patent cooperation or work sharing arrangements with the major patent offices such as the Trilateral or IP5 offices will be to effectively retain and safeguard the capacity to conduct such robust search and examination. Technical assistance programmes, examiner exchanges can expose and orient patent examiners from developing countries not only to the search tools, systems and techniques, but also to certain perspectives through which patent claims could be deemed to satisfy the criteria of patentability in a flexible way. For example, though under a strict interpretation a selection patent claim could be considered to be not novel as it is previously disclosed in an earlier application, patent examiners receiving technical assistance from the EPO could consider such claims to be permissible.Footnote 121 Therefore, developing countries must ensure that patent examiners are exposed to trainings that offer different perspectives, and expose them to the development and public policy implications of the possible approaches that could be taken to interpret the patentability of a claim.

With regard to work sharing collaborations such as the PPH that go beyond merely offering access to search and examination results of one office to another but encourage reliance on the reports produced by an office of first filing or examination, developing countries should exercise caution. A prudent approach in this respect, which some developing countries have taken,Footnote 122 is to limit such work sharing arrangements to exclude particularly sensitive fields of technology such as pharmaceuticals, and limit the number of applications to be processed under such arrangements.

6.3 Use of Technology

Digitization, ICT, machine translation, etc. have immensely aided patent offices to stay connected and share information rapidly and securely. While continuing to expand the use of such technologies to enable access to more information to conduct more comprehensive search and examination, facilitate electronic filing of patent applications, communication between the patent office and the applicants during the search and examination, as well as receiving oppositions or third party observations, there is need for caution with regard to use technologies to the decision-making itself. A number of patent offices have undertaken projects to use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for patent classification as well as patent search. However, AI and machine learning tools can be used to even conducting the patent examination itself.Footnote 123 Therein lies the risk for developing countries, particularly those which fully rely on the decisions of foreign patent offices, such as under the validation agreements with the EPO.

6.4 Administrative Law Oversight

The global network of patent offices is a reality. If utilized appropriately, collaboration between patent offices can certainly provide efficiency gains for the conduct of the business of patent offices. At the same time, patent offices also have a regulatory role to play in the public interest by ensuring as far as possible that patents of questionable validity are not granted. The patent cooperation and work sharing arrangements that patent offices engage in with their counterparts from other countries obviously have a bearing on this function. However, these arrangements are often implemented as pilot projects, as cooperation activities under MOUs. At most, implementation of these activities would involve a revision of the regulations, rules or guidelines developed by the patent office as subordinate rules under the framework of the patent law enacted by the legislature. Thus, implementation of principles of administrative law can be crucial to ensure that the functions of the patent office as a sentinel of the public interest through the conduct of robust search and examination to decide on the grant of a patent in accordance with the national law is safeguarded, while attempting to secure speed and efficiency in disposal of the workload of patent offices through mutual collaboration. Thus, patent offices should be required to undertake sufficient public consultations prior to engaging in collaborative work sharing arrangements, as well as when considering expansion of the scope of such collaborations. Legislative oversight should also be exercised to ensure that collaborations between patent offices are effectively enabling, and not limiting, the implementation of the substantive patentability criteria under the national law.

7 Conclusion

Rigorous examination of a patent application to determine whether a patent claim satisfies the requirements of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability, and sufficiently discloses the best enabling mode of working the claimed invention, is the most important role of a patent office. This makes it critical that patent offices are able to perform this role well by ensuring that the patentability thresholds as defined under the national law and the public policy objectives that inform the law, are given effect to in the process of interpretation of the patentability of a technical patent claim. Thus, how a patent examiner views a claim matters. The perspective of the examiner can be influenced by technical assistance or administrative collaboration arrangements between patent offices. Patent offices in developing countries also face challenges, such as limited human resources for patent examination, surge in the number of patent applications in different technical fields, associated backlogs, and the pressure to speedily dispose the applications. These challenges can impact the rigorous application of the patentability thresholds as patent offices have to make a choice of prioritizing between speed and efficiency in completing the search and examination work and robustness of the examination. Increasing human resources for search and examination, use of automation technologies and leveraging the search and examination capacity and work products of other patent offices are possible approaches being deployed by patent offices to address this challenge.

Digitization and use of ICT systems has enabled offices to collaborate in conducting search and examination work more easily. However, this has also enabled the major patent offices such as the Trilateral Offices and the IP5 to play an influential role in influencing the work of other patent offices. Indeed, work sharing has been explicitly recognized as part of an agenda of achieving a harmonized global patent system. While the negotiations for a Substantive Patent Law Treaty was unsuccessful in WIPO, soft law reforms of the PCT system has been undertaken through an incremental approach, and work sharing arrangements developed by the major patent offices outside the PCT system are also being promoted both in terms of their integration to the PCT through pilot projects (such as the PCT-PPH pilot project by EPO) as well as experience and best practices sharing sessions on “quality of patents” in the WIPO SCP discussions.

The nature of collaborations between patent offices vary. While some patent offices have entered into agreements to outsource search and examination work to the more resourceful patent offices or recognise within their territories the patents granted by another office (such as under the EPO validation agreements), other offices may collaborate merely to share information and documents relating to prior art, and search and examination results. Many patent offices have also agreed to engage in projects such as the PPH with one or more countries wherein they agree to not only share the search and examination results, but to use the search and examination results on a claim by one office to accelerate the examination of the claim in the other office. While engaging in such arrangements, patent offices in developing countries should ensure that the flexibility available to them under the TRIPS Agreement to apply the patentability criteria as defined under the national law and policy is effectively safeguarded. Some patent offices have excluded sensitive sectors such as pharmaceuticals from their PPH agreements and have limited the number of applications to. Which the accelerated procedure could apply. However, it is possible that over time the PPH agreements could be expanded to include technology sectors that are currently excluded and could also be extended to patent applications from more countries. Patent offices in developing countries should also ensure that patent examiners are exposed to trainings that offer different perspectives on how patent claim could be interpreted differently by application of the patentability criteria under a strict or relaxed standard.

Patent cooperation and work sharing presents both opportunities and challenges for patent offices. Patent offices in developing countries could engage in cooperation with each other in a South-South framework to undertake examiner exchange programmes, sharing of sector specific guidelines on patent examination, sharing of search and examination reports, objections or questions raised in first examination reports (FER), results of pre-grant opposition proceedings, and information on post-grant revocation or grant of any compulsory license on a patent. South-South cooperation should be undertaken with a focus on enabling patent offices to utilise their resources for ensuring robust examination of patent applications. A priority area of focus in this regard should be on the examination of pharmaceutical patent applications.

Finally, cooperation between patent offices typically take place in the form of projects implemented under MOUs, which are undertaken in exercise of the administrative discretion that patent offices have. While exercising such discretion, it would be pertinent for patent offices to also assess the implications of such cooperation on their regulatory function of ensuring grant of robust patents in the public interest. It would this be pertinent to undertake public consultations and also exercise legislative oversight by application of the principles of administrative law, to ensure that cooperation that patent offices enter into in exercise of their discretionary powers, are exercised in the public interest and do not impede the attainment of the public policy objectives that inform the patent law.

Notes

- 1.

Invalidation of a patent can take several years of litigation, during which period the patent can still be enforced, and involve investment of substantial technical and financial resources which may be difficult to access or afford, particularly in developing countries. Correa (2014a).

- 2.

Ibid, p. 2; the number of patent applications and grants have increased significantly in many countries without a corresponding genuine increase in innovation due to the application of low requirements of patentability.

- 3.

Article 27.1 of the TRIPS Agreement requires patents to be granted in all fields of technology without discrimination as long as the patent applications satisfy the patentability criteria of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability. However, WTO members can apply their own definitions of these criteria, and in doing so, can differentiate between fields of technology. See Correa (2012).

- 4.

The boundaries of patentability of claimed inventions have been stretched through the adoption of a number of legal fictions. For example, it is assumed that a fictional ‘person skilled in the art’ against whose level of knowledge the inventiveness or non-obviousness of a claim is to be determined, is a person of ordinary knowledge to whom even trivial developments would appear to be inventive. However, there is no obligation under any international agreement to apply such legal fictions. Correa (2014b).

- 5.

One study found that in spite of stricter thresholds of patentability established under the patent law in India, in some instances the Indian patent office has granted patent claims that had been rejected in the US and EU in spite of the application of liberal thresholds of patentability. Chaudhuri et al. (2010); a recent study found a 72% error rate in the grant of secondary pharmaceutical patent applications in India, in spite of the high threshold established under the Indian patent law (Ali et al. 2018).

- 6.

However, sometimes backlogs in processing patent applications could also lead to withdrawal of patent applications and save the resources of a patent office.

- 7.

Cruz and Olivos (2019).

- 8.

See Shadlen (2013), p. 87.

- 9.

Ibid, p. 88.

- 10.

It is reported that the Indian Patent Office has substantially reduced backlogs by hugely augmenting its human resources, alongside amendments of processing timelines and use of ICT tools to better leverage its internal examination capacities. The Brazilian Patent and Trademark Office has also substantially reduced backlogs through a increasing the number of patent examiners in parallel to accelerating examination of patent applications in specific sectors and utilizing prior art search conducted by other offices on corresponding applications. See, e.g., Jayakumar (2017) and Nunes and Romano (2019).

- 11.

See, e.g., European Commission (2009), pp. 385–390 (describing how strategic patenting is used by pharmaceutical companies to block the entry of generic competition).

- 12.

See generally, Dhavan (1990), p. 131 (tracing the historical evolution of the Paris Convention, its evolution towards greater protection for the patentee and less regulatory authority for member States, and the marked absence of any attempt to properly examine the public interest).

- 13.

If States act in a certain consistent manner on a given subject matter over a period of time, it is assumed under the general principles of international law that they are acting in such a manner because they have a sense of a legal obligation, and hence such practice can be regarded as a rule of customary international law. If a majority of States believe that such a customary norm cannot be persistently objected to, it can acquire the status of a peremptory norm of international law, that would be binding on all States. Baker (2010), p. 173.

- 14.

Syam (2019), p. 18.

- 15.

Ibid.

- 16.

Assemblies of the member States of WIPO (2002).

- 17.

Ibid [10].

- 18.

Ibid [12]–[32].

- 19.

Drahos (2008a), p. 151.

- 20.

Text to n 25.

- 21.

Drahos (2008a), p. 6.

- 22.

Ibid. For example, the 1995 annual report of the EPO which tacitly admits that its technical assistance to the ASEAN countries was driven by the objective of easing the process of prosecution of patent applications of European origin filed in those countries, through training of examiners, by incorporating search and examination results from other offices into the patent grant procedures of the patent offices that are given training, and automation of systems of patent administration.

- 23.

European Patent Office (2017).

- 24.

European Patent Office (n.d.)

- 25.

See, e.g., European Patent Office (2016).

- 26.

European Patent Office (2017).

- 27.

't Hoen (2020).

- 28.

Correa (n 4), pp. 13–16.

- 29.

Ibid, pp. 2–3.

- 30.

Ibid, p. 3.

- 31.

See, Drahos (2008b).

- 32.

Ibid, p. 508. See generally, Correa (n 1), pp. 3–21 (describing legal and policy measures taken by various countries, including major developed countries, to reduce the proliferation of patents).

- 33.

Drahos (2008b), p. 508 (explaining how the backlog of patent applications beyond their search and examination capacity has driven the Trilateral offices to explore means to reduce pendency and ensure timely and expedited disposal of patent applications. Long-standing cooperation with the Trilateral Offices has also imbibed the quest for productive efficiency in the patent offices from developing countries).

- 34.

- 35.

Ibid.

- 36.

See, e.g., WIPO (Standing Committee on the Law of Patents) (2013a), Proposal by the delegations of the Republic of Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States of America regarding work sharing between offices in order to improve efficiencies of the patent system (2014), Proposal by the delegation of the United States of America on the study of worksharing (2015), and Proposal by the delegations of the Czech Republic, Kenya, Mexico, Singapore and the United Kingdom (2018).

- 37.

- 38.

The PCT international phase timelines allowed a patent applicant to delay the start of national processing of an international patent application. Under the Paris Convention, a patent must be filed in a country within 12 months from the date of first filing of the application in another country. Under PCT, while the international application must be filed within this 12-month period, the national phase entry can be delayed to 30 months from the priority date. This was done to enable an applicant to assess the viability of obtaining patent protection in a territory for a claimed invention before actually pursuing national search and examination. See Mossinghof (1999) (explaining that this was particularly important for pharmaceutical companies by enabling them to file a patent on a promising drug and then using the opportunity of delayed national examination in designated countries to assess the viability of pursing a national patent in a country based on factors as such clinical trial outcomes).

- 39.

Drahos (2008a).

- 40.

WIPO, ‘Patent Cooperation Treaty (“PCT”) (1970)’ (wipo.int) <http://www.wipo.int/pct/en/treaty/about.html> accessed 9 May 2020.

- 41.

For example, article 18.7 of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement makes ratification or accession to the PCT a mandatory obligation for all countries that are party to the treaty. Government of Canada, ‘Consolidated TPP Text – Chapter 18 – Intellectual Property’ (international.gc.ca) https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/tpp-ptp/text-texte/18.aspx?lang=eng.

- 42.

May (2007), p. 49.

- 43.

According WIPO statistics, more than 70% of International Search Reports under PCT between 2000 to 2018 have been issued by EPO, USPTO and JPO. Though the number of International Search Reports from China and South Korea have significantly increased in recent years, the EPO, USPTO and JPO continue to produce more than 65% of these reports between 2015 to 2018. See World Intellectual Property Organization (n.d.).

- 44.

See, e.g., Shashikant (2014), pp. 17–21 (pointing out that most patent applications in the African Regional Intellectual Property Office (ARIPO) are filed through the PCT route while the ARIPO has a capacity of 12 patent examiners, and that ARIPO relies heavily on the results of the PCT or foreign search and examination results and on the EPO guidelines).

- 45.

See, e.g., WIPO (Committee on Reform of the Patent Cooperation Treaty) (2001) (proposal to make PCT search and examination binding on PCT Contracting Parties while simplifying PCT procedures for patent applicants); WIPO (Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) Working Group) (2018), (proposal by the WIPO secretariat to amend the PCT Regulations to enable national patent offices to delegate their national office functions to the office of any other PCT Contracting State or an intergovernmental organisation); also see, Rathod and Ali (2018).

- 46.

WIPO (International Patent Cooperation Union (PCT Union) Assembly) (2000a), (the proposal pointed to the need to simplify PCT procedures and converge PCT and patent office practices to the extent possible to facilitate obtaining worldwide patent protection through simplified application, preferably in electronic format, and minimize the distinction between international and national processing of the patent applications. Eventually, the proposal envisaged adopting procedures that would enable substantive rights to be granted through the PCT. More specifically, the changes proposed to the PCT system in the first stage included the following: elimination of the concept of designation of PCT Contracting Parties in respect of which an international patent application is filed, thus making an international application applicable to all PCT Contracting Parties and relieving the applicant from paying the designation fees; eliminating residency and nationality requirements for filing international patent applications, thus enabling any person regardless of residence or nationality to file a PCT application in any patent office of a PCT Contracting Party; aligning PCT filing date requirements to the PLT; aligning PCT rules on filing of missing parts in an application to the rules in the PLT; enabling an applicant to request supplementary search and examination from multiple International Search Authorities; subjecting all PCT applications to a preliminary international examination following the international search report; enabling further delaying of national phase entry of an application at the option of the applicant; combining search and examination processes; and, facilitating electronic publication of the application and transmission of search and examination results. The comprehensive reforms envisaged were regional consolidation of international search and examination authorities; eliminating the distinction between national and international applications to avoid duplication of processing the application in the international and national phases; making positive examination results from certain PCT international search and examination authorities binding on Contracting States; and, allowing for further deferment of national phase entry of an international application at the option of the applicant).

- 47.

WIPO (International Patent Cooperation Union (PCT Union) Assembly) (2000b).

- 48.

See, WIPO (2001) (for the proposals made by the Austria, Australia, Canada, Cuba, the Czech Republic, Denmark, EPO, France, India, Israel, Japan, Republic of Korea, the Netherlands, Spain, Slovakia, Switzerland, Turkey, the UK and the USA).

- 49.