Abstract

This chapter discusses the exemption from liability of patent infringement for activities related to regulatory approval for medicines, also known as the “regulatory review” or “Bolar” exception. The Bolar exception supports the market entry of generics by allowing the use of a patented invention by a third party without the consent of the patent holder for the sole purpose of obtaining regulatory approval. This constitutes an important defense for generic manufacturers when undertaking activities such as studies and trials to provide the information required by regulatory agencies. In this regard, the Bolar exception can respond to a public policy objective of facilitating market entry of generics to support competition and exerting downward pressure on prices for medicines. The Bolar exception is included in many country patent laws and is compatible with international legal instruments regarding patent law.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Exceptions to Patent Rights

A patent grants the patent holder the exclusive right to exclude others from making, using, importing, and selling the patented innovation for a limited period of time.Footnote 1 Most, if not all, patent laws exclude certain matter from patentability, and also limit the rights of patent holders by way of exceptions.Footnote 2 These have the important function of defining spaces of freedom of action, wherein obtaining permission from patent right holders is not required.

International patent law as regulated by the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)Footnote 3 contains an overall obligation for members of the WTO to grant patents for inventions that meet the criteria of patentabilityFootnote 4 in all fields of technology. Nonetheless, certain exclusions from patentable inventions are permitted.Footnote 5

Exceptions allow activities that would otherwise be considered patent infringement. They may remove liability for infringing patent rights, by deeming certain acts as non-infringing (as is the case of the Bolar exception analysed in this chapter). WTO members have greater freedom to introduce exceptions to the rights of patent holders in their legal systems, as compared to exclusions from patentable subject matter. Rather than defining the exceptions, the TRIPS Agreement allows Members to develop limited exceptions so long as these comply with certain conditions.Footnote 6 Exceptions that can be found in many jurisdictions are exceptions for private, non-commercial use, or to promote research or experimentation.Footnote 7 Generally, the Bolar exception can be considered to be a specific type of experimental use exception.

Members have discretion to decide what exceptions to establish, consistent with the TRIPS Agreement. This has the advantage of allowing countries to determine what exceptions are most relevant to their evolving domestic priorities and various policy considerations. These may include, to confine the patent right for the subject matter that it was intended, and for protecting third party rights and the public interest.Footnote 8 Exceptions to patent rights may be stipulated in legislation or judicially created—developed through case law. Domestic exceptions can however be challenged under the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU). There has so far been a single instance of a challenge to exceptions that limit patent rights, in the panel Canada-Pharmaceutical Patents case.Footnote 9 The panel decision is not a binding precedent for Members in developing their exceptions that are compatible with the TRIPS Agreement. Moreover, given that the decision was not appealed, the Appellate Body did not provide its own interpretation.Footnote 10

2 Rationale for the Bolar Exception

When the patent monopoly expires, the patent ceases be a legal obstacle for a competitor to produce and commercialize the protected product or use the protected process. However, other market barriers may remain. Pharmaceutical products must meet regulatory requirements for authorization to be placed on the market. The patent status of the originator product can impede the competitor from being able to start work to meet regulatory requirements in order to be able to place the product on the market once the originator patent expires. Unless such work is permitted during the patent term, by an exception. Without the Bolar exception, or a broad experimental use exception that includes acts to provide information for regulatory approval, the competitor will not be able to prepare for regulatory approval until the patent expiry. This means that, as obtaining the marketing approval for a genericFootnote 11 medicine takes time, the patent monopoly for the originator is practically extended further in time than originally conceived. In recognition of this problematic, the Bolar exception is present in many national jurisdictions.

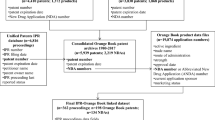

A review of the process of market authorization for medical products is presented below, prior to discussing in more detail examples of how the Bolar exception is crafted in various jurisdictions.

2.1 Marketing Authorization of Medical Products

Governments have an important role in formulating laws and regulations to define and control the national market in medical products in the interest of public health.Footnote 12 The national medicine regulatory authority aims to protect public health by ensuring that a product is safe, efficacious and of good quality before it reaches a patient. Thus, national medicine regulatory authorities around the world subject pharmaceutical products to premarketing evaluation and marketing authorization to ensure that they conform to required standards.Footnote 13 The marketing approval system is applied in accordance to national law. All medicines have to be authorized before they can be marketed. The manufacturers of any medicine, whether it is a brand-name originator or a generic,Footnote 14 need to comply with the requirements. A granted marketing authorization is valid in the geographical territory in which it is applied for.Footnote 15

The specific regulatory requirements for a medical product to be marketed may vary. For chemically synthesized pharmaceuticals, regulatory authorities generally require that generic products demonstrate the same bioavailability and often bioequivalence of the generic medicine to a reference product. Producing a full dossier, including showing the results of pre-clinical tests and clinical trials to show safety and efficacy of the product, can require significant investment and time. In the case of requests for approval for local production of medicines or import of medicines already marketed and approved in third countries, requirements of local clinical trials may be waived. Hence, if a medical product is a generic of a reference medical product, it may receive an abridged process for compliance with the premarketing evaluation and marketing authorization.

Marketing approval or licensure of biologics—referring to medical products that are made from living organisms-, and biosimilarsFootnote 16 may be subject to specific and more stringent requirements. There is significant divergence on approaches being taken by regulatory agencies in this area and debate are ongoing on the current guidance by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the matter.Footnote 17

2.2 Relationship of Patent Protection, Marketing Authorization and Supplementary Legal Protection

The relationship between patent protection and marketing authorization of medical products at first would appear to be very weak. All medical products are subject to regulatory requirements, regardless of their patent status. Moreover, in accordance to patent law, once patent protection expires, competitors should have free entry. However, in practice, questions of marketing authorization and patent protection for medical products have become more intertwined, as policy makers juggle in balancing between innovation and competition incentives, under pressure from a wide range of stakeholders.

In principle, the patent status of the originator medical product should be irrelevant for purposes of the regulatory requirements for approval of generics or biosimilars. However, some countries have adopted a patent linkage regime to link the grant of marketing approval by a regulatory authority with the patent status of an originator medical product.Footnote 18 This system poses the additional burden on the regulatory authority to review whether there may be a patent infringement before it will issue marketing approval for a new product and creates new restrictions for the registration of generic and biosimilar products.

In addition, patent term extensions may be available in some jurisdictions under the rationale of compensating for delays in examination or simply because the product is subject to regulatory review. These provisions, generally incorporated in free trade agreements entered into by the USA and the European Union,Footnote 19 result in further delays of generic and biosimilar market entry.

The increased laxity in the criteria applied in patent examination in some jurisdictions also enables the pharmaceutical industry to employ strategic patenting tactics such as “evergreening” to artificially extend the patent term for profitable medical products.Footnote 20 Moreover, in some jurisdictions, the patent incentive for innovation is now supplemented with other legal exclusivities that support the originator in delaying entry of generics or biosimilars after the patent term expiry, including data and market exclusivityFootnote 21 and supplementary protection certificates.Footnote 22

On the other hand, in order to promote competition, regulatory authorities may provide abbreviated pathways for the approval of generics and more recently, for biosimilars. The policy rationale of the Bolar exception, where available in national patent laws, also aims to lower product development costs, expedite regulatory approval and ease market entry.

In this sense, the balance between innovation and competition no longer rests solely on the design and implementation of the patent system—but on the myriad of other related instruments that are crafted to respond to the variety of interests involved and overall complex ecosystem of medical product development, procurement and supply.

2.3 Role of Generic and Biosimilar Competition in Promoting Access

Medicine prices decrease significantly after patent expiry.Footnote 23 The increased use of generic medicines is an important measure for cost-containment in pharmaceutical procurement. Generics increase competition and lower prices for medicines that improve access and lower medicine purchase expenditures for governments, to sustain their healthcare systems. This is of particular relevance today in the context of rising drug spending, affected by high prices for some medicines, in particular of biologics such as monoclonal antibodies, notably in low and middle income countries where in addition to limited government budgets for public procurement, out-of-pocket purchases are high.

In the United States, the top twelve grossing medicines, mostly biologicals, have increased by 68% from 2012 to 2018 and cost $96 billion to health insurers, government payers, and consumers in 2017 alone.Footnote 24 A recent US FDA report from December 2019 compared medicines that had initial generic entry between 2015 and 2017 and found that the median price of generics relative to brands is 40%.Footnote 25 In Europe, pioneer in biosimilar registration and the largest market for global biosimilar sales, biosimilar competition has significantly reduced prices for biologicals.Footnote 26 Nonetheless, the overall market penetration of biosimilars remains low, though expiration of patent and exclusivities of the originator biologics is increasing opportunities for further savings.Footnote 27 Currently 61 biosimilars have been approved in Europe since the establishment of the regulatory framework for registration of biosimilars in 2005.Footnote 28 India is the largest provider of generic medicines globally, occupying a 20% share in global supply by volume, and with increasing capacity for production of biosimilars.Footnote 29

The extent of the cost-saving potential from switching from originators to generic products may nonetheless vary among countries depending on, among other factors, differences in the timing of patent expiries, the type of generic medicine pricing policies they apply,Footnote 30 dispensing practices, the market share of generic medicines. Expanding biosimilar uptake presents additional challenges, including the extensive litigation actions by biopharmaceutical manufacturers, the need for greater acceptance by physicians and patients of biosimilars as safe and effective alternatives to reference-biologic products.

On a more global level, the role of generics in increasing access is evident in relation the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The decline in mortality rates between the mid 1990s to early 200s is attributable in large part to the expanded access to generic antiretrovirals (ARVs), mostly produced in India, that greatly reduced prices and allowed for treatment expansion. In Brazil, with the production of local generic ARVs, the prices fell by more than 70% in four years. By 2000, AIDS mortality rate in Brazil had been halved and HIV-related hospital admissions had fallen by 80%.Footnote 31

3 History of the Bolar Exception

Patents and other exclusivities constitute barriers to market access for generics and biosimilars. The Bolar exception is a tool within patent law that supports market entry of generics and biosimilars, by allowing manufacturers to prepare these products in advance of the expiration of the originators’ patents.

The history of the Bolar Exception is well documented. It stems from US Congress reaction to the US Court of Appeals Federal Circuit 1984 decision in Roche Products v Bolar Pharmaceutical Co. where it was held that the experimental use doctrine did not protect the “limited use of a patented drug for testing and investigation strictly related to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug approval requirements” and found that Bolar’s experimental use in this case had definite, cognizable, and not insubstantial commercial purposes.Footnote 32 The Generic Pharmaceutical Industry Association (GPIA) had shown in its amicus curiae that various generics had been tested prior to patent expiry, and argued that the decision essentially allowed originator manufacturers to retain market exclusivity for their products beyond the duration of the patent terms because generic manufacturers could not even start developing and seeking approval for competing generic products until after the originator patent expired.Footnote 33 Soon after, the US Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, 35 U.S.C. § 271(e) (2003). The Hatch-Waxman Act made significant changes to US patent law with the aim to encourage innovation in the pharmaceutical industry while facilitating the speedy introduction of lower-cost generic medicines, thereby attempting to get a compromise between the interests of the research based and generic segments of the industry. Among the changes introduced, was the Bolar exception codified as 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1) that reversed Roche v Bolar court of appeals decision:

It shall not be an act of infringement to make, use or sell a patented invention … solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the manufacture, use, or sale of drugs or veterinary biological products.

Judicial interpretations of 271(e)(1) have given a broad reading of the subject matter (i.e. originators, biologics, generics, biosimilars, medical devices) and permitted the coverage of a range of activities under the exemption.Footnote 34

Many countries have subsequently introduced a similar regulatory review exception in their patent laws, as will be discussed further in section 5 below.

4 Consistency with Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement

A WTO dispute settlement panel examined the regulatory review provision of the Patent Act of Canada in the Canada–Pharmaceuticals Patent caseFootnote 35 and confirmed that it conforms with the TRIPS Agreement. The panel found that there was no conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent (Article 28.1 of the TRIPS Agreement) and that it was justified under Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement (exceptions).

The Canada Patent Act, Section 55.2(1) reads: “It is not an infringement of a patent for any person to make, construct, use or sell the patented invention solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required under any law of Canada, a province or a country other than Canada that regulates the manufacture, construction, use or sale of any product.”

The panel held that the provision was justified under Article 30 by meeting all of the three cumulative criteria: it is a “limited” exception, not unreasonably interfering with the normal exploitation of the patent, and not unreasonably prejudicing the rights of the patent holder, taking into account the legitimate interests of third parties.Footnote 36

In the WTO Council for Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Council)Footnote 37 and at the World Intellectual Property Organization,Footnote 38 countries have continued to exchange on the rationale for inclusion of the exception in their laws as a mean to balance the private interests of patent right holders and public interest, and experiences in its use.

5 Crafting National Legal Frameworks for the Bolar Exception

The Bolar Exemption is recognized in various national patent laws, generally with the aim to support entry of competitor products upon patent expiry of the originator product. A WIPO study from 2018 indicates that at least 65 countries and two regional instruments provide for a Bolar exception.Footnote 39 While the objective of the Bolar exception is the same—to avoid delays in market entry for competitor products—there can be significant divergences among national approaches, including on scope and implementation.

In fact, for the design of a Bolar exception, there can be numerous alternative approaches. Professor Correa has advanced that “the broader the formulation of the exception in terms of covered products, sources of samples, type of trials allowed, time to undertake them, and geographical scope, the more competitive environment is ensured that will benefit consumers, health providers and other public agencies.”Footnote 40 The policy choice for designing a broader Bolar exception is more favourable to the objective of promoting competition.

Several countries, such as the United Kingdom and Ireland, have in recent years amended their patent laws to broaden the scope of the Bolar exception. The extension of the Bolar exception has also been under consideration in the EUFootnote 41 given the divergences in current implementation throughout the member States and in the context of how a future Unified Patent Court (UPC) may apply the Bolar exception.Footnote 42 A study by the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition prepared for the European Commission recommended that the EU member States adopt a broader than the minimum standard currently provided for under Art. 27(d) UPCA, in following the national Bolar exceptions in Germany, Ireland, Italy, France, among other EU member States.Footnote 43 The economic impacts of extending the Bolar exception in the EU to cover any medicines (not limited to products following an abridged marketing authorisation only), have been estimated as cost savings from patent screening of up to €23-€34.2 million per year.Footnote 44

In order to well define the Bolar exception, it may be preferable to design it as a specific exception, as opposed to inclusion as part of a general research or experimental exception.

The Bolar exception can be crafted to cover all regulated products, including but not limited to health-related products for human use, such as medicines and medical devices. Other regulated products covered in some Bolar exceptions include veterinary medicines and plant protection products.

The scope of the activities should be clearly defined. These should relate to obtaining marketing approval for generics and biosimilars, but may also extend for acts relating to medical devices (as provided for in the US) and innovative medicines (for example to carry out health technology assessments as in the Bolar exception in the UK Patents Act).

It is not necessary to restrict the user of the Bolar exception to the party that would be requesting the marketing authorization. It can also include acts by third parties involved in supplying materials to a company to run tests and trials related to obtaining marketing authorization for a generic or biosimilar.

A clear definition of the scope of the permitted acts is one of the critical aspects of a Bolar exception so as to provide legal certainty of the safeguards it provides against patent infringement and to the rights of patent holders. Acts that are related to obtaining marketing approval that should be covered include studies, trials and experiments required for obtaining marketing approval in the country, as well as for obtaining marketing approval in other countries. As noted earlier, third party activity for the company seeking marketing approval, such as delivery of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) to carry out tests or trials when the company is unable to produce the API in-house, can also be included.Footnote 45

6 India Bolar Exception: Recent Developments

The design and implementation of the Bolar exception is of particular relevance in countries that have domestic production capacity for generics and biosimilars. The Bolar exception in Indian legislation is of special interest, as India, as noted, is a global leader in the global supply of affordable generic and biosimilar products. The Bolar exception contributes to a favorable environment for the generic and biosimilar industry in India to develop and expand.

The Indian patent act in Section 107A includes a broad Bolar exception. It reads: “any act of making, using, selling or importing a patented invention solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required under any law in India, or in a country other than India, shall not be considered as infringement of patent rights.”Footnote 46

The exception applies to any regulated sector, and extends to acts done for submission of information not only in India but in any other country. The scope of acts covered can include the manufacture of the patented protected product, export of an API or finished formulation by a generic company, conduct of clinical trials, or import of the API or formulation by a third party to support relevant regulatory approvals in India or other countries.

While the Section. 107A is clearly worded, there has been significant litigation with respect to this provision, and, accordingly the Indian judiciary has provided important interpretation of its scope. A recent case tested in particular the definition of “selling” and determined that it allows export of a patented product for generation or submission of information for seeking regulatory approval in India or other countries, without such export constituting an act of patent infringement. A Division Bench of the Delhi High Court held that export for the purpose of conducting development/clinical studies and trials is within the ambit of the Indian Bolar exception.Footnote 47 The Court established an indicative list of factors to determine whether the export is ‘reasonably related’ to the research purpose or not.

The court also clarified that section 107A is not to be treated as an exception to section 48 of Indian Patent Act: “Its history of interpretation by TRIPS, the discussion in the Parliamentary Joint Committee Report, all clearly point to its being a special provision that deals with the rights of the patented invention for research purposes.”Footnote 48

The relationship of the Bolar exception with the terms of a compulsory license was also considered by the court. As noted by Indian delegation to the WTO, “Bolar exceptions have an important link with compulsory licensing. The absence of the Bolar exceptions can severely affect the ability of a country to effectively utilize compulsory license provisions when considered necessary.”Footnote 49

In Bayer Corporation and Ors. v. Union of India and Ors., Bayer had filed a suit for infringement of Patent against Natco, a generic producer. During the pendency of the suit, Natco obtained a compulsory license for the same patent for the territory of India. Bayer filed a writ petition in the High Court of Delhi seeking a direction to the Custom Authorities to seize the consignments for export of the products covered by the compulsory license (CL) manufactured by Natco, on grounds that the export violated the terms of the CL. The Court passed an interim order to restrain Natco from the export. In parallel, Natco requested and obtained permission to export 1 kg of API to China to conduct clinical studies and trials for regulatory purposes. Bayer considered that the API sale was an infringement of the patent in violation of the CL terms. Natco argued that it was covered by the Bolar exemption as the export was for regulatory purposes.Footnote 50 In its decision the Court noted that “it is..of the opinion that Natco’s status as compulsory licensee did not place it under any additional statutory bar from exporting the product, as long as the underlying condition in Section 107A was satisfied”.Footnote 51

7 Conclusions

Policy makers can apply different approaches to address the competing interests of promoting innovation and the discovery of new medicines while at the same time fostering competition through the development and market entry of lower cost generic and biosimilar products. The policy approach should be in line with public health policies, i.e. to support access to medicines for all, and informed by the domestic context of the pharmaceutical industry.

Without the regulatory review or “Bolar” exception, competitive products such as generics and biosimilars would not be able to enter the market for prolonged periods following patent expiry of originator products. The safeguard against patent infringement for acts covered by the Bolar exception supports the regulatory approvals for generics and biosimilars without delay. Policy choices to expand the term of patent protection, introduce test data exclusivity or patent linkage can have the effect of increasing barriers for generic and biosimilar market entry.

A broad and well-defined Bolar exception, as described in this chapter, is suited to the objective of promoting timely regulatory approval for generics and biosimilars to lower costs for health systems and improve access to medicines.

Notes

- 1.

The TRIPS Agreement states that the available term of protection must expire no earlier than 20 years from the date of filing the patent application. In some jurisdictions the term may be extended, for example in the United States through Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE). The extended exclusivity delays generic competition that can negatively affect access to medical products in the trading partners, and pressures patent offices to examine patent applications more expediously. Patent term extensions are often requirements in regional trade agreements involving the United States and European Union. See Correa (2017).

- 2.

Bently (2011), pp. 315–347.

- 3.

Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights of 1994; being Annexe 1C to the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, April 15, 1994 (hereafter “TRIPS Agreement”).

- 4.

TRIPS Article 27.1 states that “…patents shall be available for any inventions…in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application.” The TRIPS Agreement does not define “invention” and “technology” and does not determine how patentability requirements should be applied. This is an important area of policy space for WTO members to define the appropriate contours of their patent laws in accordance to meeting the objectives of the patent system and against other objectives such as public health policy. See Correa (2014).

- 5.

The permissible exclusions are defined in the TRIPS Article 27.2 and Article 27.3.

- 6.

TRIPS Article 30 states that “Members may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent, provided that such exceptions do not unreasonably conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner, taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties.”

- 7.

See Correa (2005).

- 8.

Dreyfuss (2018), p. 8.

- 9.

World Trade Organization (2000)

- 10.

Mercurio and Tyagi note that the Appellate Body has supported a broad interpretation of exceptions based on the Appellate Body Report, European Communities—Measures Concerning Meat and Meat Products (Hormones), ¶ 104, WT/DS26/AB/R, WT/DS48/AB/R (Jan. 16, 1998), (“[M]erely characterizing a treaty provision as an ‘exception’ does not by itself justify a ‘stricter’ or ‘narrower’ interpretation of that provision than would be warranted by examination of the ordinary meaning of the actual treaty words, viewed in context and in the light of the treaty’s object and purpose, or, in other words, by applying the normal rules of treaty interpretation.”). Mercurio and Tyagi (2010), 262, footnote 68.

- 11.

In this chapter the term generics is used to describe chemical, small molecule medicinal products that are structurally and therapeutically equivalent to an originator product. Generics are interchangeable with an originator product.

- 12.

See World Health Organization (1999).

- 13.

See World Health Organization (2011).

- 14.

A generic medicine is an equal substitute for an already marketed brand-name drug and is not protected by a patent in force. Generics are generally commercialized under a non-proprietary name. Pharmaceutical substances and active pharmaceutical ingredients are given unique, non-proprietary, generic International Nonproprietary Names (INN). A generic may also be marketed under its own brand name.

- 15.

However, many national regulatory authorities have entered into harmonization initiatives or mutual recognition agreements. For example, in the European Union there are different authorization routes and some medicines go through a centralised marketing authorisation valid in all EU member States.

- 16.

Another term used for example by the WHO is “similar biotherapeutic products”, to refer to a biological product which is similar in terms of quality, safety and efficacy to an already licensed reference biotherapeutic product.

- 17.

- 18.

- 19.

See Daniel Opoku Acquah, Revisiting the Question of Extending the Limits of Protection of Pharmaceutical Patents and Data Outside the EU – The Need to Rebalance, Research Paper 127, December 2020, South Centre, https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/RP-127.pdf.

- 20.

- 21.

See Correa (2013), pp. 16-/173.

- 22.

The experience with these new exclusivities or sui generis IPRs for regulated products has also led to the adoption of new exceptions. See Seuba (2019), pp. 876–886, https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpz108.

- 23.

Vondeling et al. (2018), pp. 653–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-018-0406-6 pmid:30019138.

- 24.

I-Mak Report, Overpatented, Overpriced: how excessive pharmaceutical patenting is extending monopolies and driving up drug prices, 2018. http://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/I-MAK-Overpatented-Overpriced-Report.pdf.

- 25.

The calculations use average manufacturer prices. Conrad and Lutter (2019).

- 26.

Gabi Journal Editor Biosimilars Markets (2020), pp. 90–92. https://doi.org/10.5639/gabij.2020.0902.015.

- 27.

OECD/European Union (2018), https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en.

- 28.

European Medicines Agency, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/.

- 29.

- 30.

The various policies include free-pricing systems (i.e. US) versus price-regulated systems (i.e. EU), reference pricing, price competition and discounts, and tendering procedures. Reimbursement policies may also affect final generic price.

- 31.

UNAIDS (2008), p. 113.

- 32.

Roche Products v Bolar Pharmaceutical Co., 733 F.2d.858 (Fed.Cir.1984) at 863.

- 33.

Krulwich (1985), pp. 519–525. Retrieved December 20, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26658803.

- 34.

See Noonan (2015), p. a020800. Published 2015 Mar 16. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a020800.

- 35.

Ibid, at 9.

- 36.

The panel found that the stockpiling provision in the Canadian Patent Act is inconsistent with TRIPS Agreement Article 28.1, as it did not satisfy the first condition of TRIPS Agreement Article 30 because it is not a “limited exception.”

- 37.

WTO document IP/C/M/88/Add.1, Minutes of the TRIPS Council, 12 April 2018, Agenda item 12: Intellectual Property and Public Interest, Regulatory Review exception, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/IP/C/M88A1.pdf&Open=True.

- 38.

WIPO draft reference document on the exception regarding acts for obtaining regulatory approval from authorities (second draft), document SCP/28/3, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/scp/en/scp_28/scp_28_3.pdf. The document is kept open for future discussion by the Standing Committee on Patents.

- 39.

Ibid, at 35.

- 40.

Correa (2016).

- 41.

The Bolar exception was introduced in Article 10(6) of the Directive 2004/27/EC of 31 March 2004, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32004L0027.

- 42.

The establishment of the unitary patent system and UPC may follow if the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPCA) enters into force. The UPCA Article 27(d) contains the Bolar Exception: “The rights conferred by a patent shall not extend to …the acts allowed pursuant to Article 13(6) of Directive 2001/82/EC or Article 10(6) of Directive 2001/83/EC in respect of any patent covering the product within the meaning of either of those Directives”.

- 43.

Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition, Study on the legal aspects of supplementary protection certificates in the EU, European Union, 2018, pp. 338–361.

- 44.

Charles River Associates (2016).

- 45.

The Dusseldorf Court of Appeal in 2013 (docket no. I-2 U 68/12, Astellas v Polharma) referred a preliminary ruling on this question to the European Court of Justice (ECJ), but the ECJ did not issue a judicial pronouncement as Astellas withdrew action against Polpharma.

- 46.

- 47.

Delhi High Court decision pronounced on 22 April 2019 on Bayer Corporation vs Union Of India & Ors. and Bayer Intellectual Property GMBH & Anr. v. Alembic Pharmaceuticals Ltd.RFA(OS)(COMM) 6/2017, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/85364944/.

- 48.

Ibid, para 89.

- 49.

Ibid at 35, para 435, page 53.

- 50.

For further analysis of the arguments made by Bayer and Natco, see Rathod (2017), available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2971521.

- 51.

Ibid at 45, para 94.

References

Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights of 1994; being Annexe 1C to the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, 15 April 1994

Bently L (2011) Exclusions from patentability and exceptions to patentees’ rights: taking exceptions seriously. Curr Leg Probl 64:315–347

Charles River Associates (2016) Assessing the Economic Impacts of the exemption provisions during patent and SPC protection in Europe, European Commission

Conrad R, Lutter R (2019) U.S. Food and Drug Administration Generic Competition and Drug Prices: New Evidence Linking Greater Generic Competition and Lower Generic Drug Prices. https://www.fda.gov/media/133509/download

Correa C (2005) The international dimension of the research exception. SIPPI (Project on Science and Intellectual Property in the Public Interest), The American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, DC. http://sippi.aaas.org/Pubs/Correa_International%20Exception.pdf

Correa C (2013) Protection of data submitted for the registration of pharmaceutical products: trips requirements and “TRIPS-Plus” provisions. In: Intellectual Property and Access to Medicines. South Centre and World Health Organization, pg. 16-/173. https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Bk_2013_IP-and-Access-to-Medicines_EN.pdf

Correa CM (2014) Tackling the Proliferation of Patents: How to avoid undue limitations to competition and the public domain. Research Paper 52, South Centre, 2014 https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/RP52_Tackling-the-Proliferation-of-Patents-rev_EN.pdf

Correa CM (2016) The Bolar exception: legislative models and drafting options. Research Paper 66, South Centre. https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RP66_The-Bolar-Exception_EN1.pdf

Correa CM (2017) Intellectual Property in the Trans-Pacific Partnership: Increasing the Barriers for the Access to Affordable Medicines. Research Paper 62R, South Centre

Correa CM (2020) Special Section 301:US Interference with the Design and Implementation of National Patent Laws, Research Paper 115. South Centre, July 2020. https://www.southcentre.int/research-paper-115-july-2020/

Delhi High Court decision pronounced on 22 April 2019 on Bayer Corporation vs Union Of India & Ors. and Bayer Intellectual Property GMBH & Anr. v. Alembic Pharmaceuticals Ltd.RFA(OS)(COMM) 6/2017. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/85364944/

Dreyfuss RC (2018) Justine Pila intellectual property law: an anatomical overview. In: The Oxford handbook of intellectual property law. Oxford University Press, p 8

Ducimetière C (2019) Second Medical Use Patents – Legal Treatment and Public Health Issues, Research Paper 101. South Centre, December 2019. https://www.southcentre.int/research-paper-101-december-2019/

European Medicines Agency., https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/

Gabi Journal Editor Biosimilars Markets: US and EU compared, Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2020;9(2):90–92. https://doi.org/10.5639/gabij.2020.0902.015

Gurgula O (2019) The ‘obvious to try’ method of addressing strategic patenting: How developing countries can utilise patent law to facilitate access to medicines. Policy Brief 59, April 2019, South Centre. https://www.southcentre.int/policy-brief-59-april-2019/#more-12341

I-Mak, Overpatented, overpriced: how excessive pharmaceutical patenting is extending monopolies and driving up drug prices, 2018. http://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/I-MAK-Overpatented-Overpriced-Report.pdf

I-Mak Report Overpatented, Overpriced: How Excessive Pharmaceutical Patenting is Extending Monopolies and Driving up Drug Prices. http://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/I-MAK-Overpatented-Overpriced-Report.pdf

Kang HN, Thorpe R, Knezevic I et al (2020) Regulatory challenges with biosimilars: an update from 20 countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33222245/

Krulwich A (1985) Statutory reversal of Roche v. Bolar: what you see is only the beginning of what you get. Food Drug Cosmetic Law J 40(4):519–525. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26658803

Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition (2018) Study on the legal aspects of supplementary protection certificates in the EU. European Union, pp 338–361

Mercurio B (2017) Patent linkage regulations. In Mercurio B, Kim D (eds) Contemporary issues in pharmaceutical patent law. Routledge, pp 97–122

Mercurio B, Tyagi M (2010) Treaty interpretation in WTO dispute settlement: the outstanding question of the legality of local working requirements. Minnesota J Int Law. 262, footnote 68

Noonan KE (2015) The role of regulatory agencies and intellectual property: Part I. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 5(7):a020800. Published 2015 Mar 16. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a020800

OECD/European Union (2018) Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union, Brussels. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en

Panel Report Canada – Patent Protection of Pharmaceutical Products WT/DS114/R, 17 March 2000. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/7428d.pdf

Rathod S (2017) The Curious Case of India’s Bolar Provision. SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2971521

Roche Products v Bolar Pharmaceutical Co., 733 F.2d.858 (Fed.Cir.1984) at 863

Seuba X (2019) The export and stockpiling waivers: new exceptions for supplementary protection certificates. J Intellect Prop Law Pract 14(11):876–886. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpz108

UNAIDS: The First Ten Years, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2008, p 113

Vaca C, Gómez C (2020) The Controversy around technical standards for similar biotherapeutics: barriers to access and competition. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.5100

Velásquez G (2018) The international debate on generic medicines of biological origin, Policy Brief No. 50, South Centre, https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/PB50_The-International-Debate-on-Generic-Medicines-of-Biological-Origin_EN.pdf

Vondeling GT, Cao Q, Postma MJ, Rozenbaum MH (2018) The impact of patent expiry on drug prices: a systematic literature review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 16:653–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-018-0406-6 pmid:30019138

WIPO. draft reference document on the exception regarding acts for obtaining regulatory approval from authorities (second draft), document SCP/28/3, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/scp/en/scp_28/scp_28_3.pdf. The document is kept open for future discussion by the Standing Committee on Patents

World Health Organization (1999) Marketing authorization of pharmaceutical products with special reference to multisource (generic) products: a manual for a drug regulatory authority. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65175

World Health Organization (2011) Marketing authorization of pharmaceutical products with special reference to multisource (generic) products: a manual for National Medicines Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs), 2nd edn. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44576

World Trade Organization (2000) Canada – Patent Protection of Pharmaceutical Products, Report of the Panel, WT/DS114/R, 17 March 2000

WTO document IP/C/M/88/Add.1, Minutes of the TRIPS Council, 12 April 2018, Agenda item 12: Intellectual Property and Public Interest, Regulatory Review exception. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/IP/C/M88A1.pdf&Open=True

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Munoz Tellez, V. (2022). Bolar Exception. In: Correa, C.M., Hilty, R.M. (eds) Access to Medicines and Vaccines. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83114-1_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83114-1_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-83113-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-83114-1

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)