Abstract

Understanding the nature of adolescent suicide ideation is of critical importance to improving suicide risk assessment, but research in this area has been limited. This chapter reviews theories and research suggesting that the form and pattern that adolescent suicide ideation takes can be informative about the risk of engaging in future suicidal behavior. These include studies examining suicide-related attention biases, duration of suicide ideation, and suicide-related imagery, longitudinal studies examining suicide ideation trajectories, and ecological momentary assessment research examining moment-to-moment variability in suicide ideation. We propose theoretically and empirically informed subtypes of suicide ideation that can be assessed during a clinical interview and that might provide additional information to clinicians about an adolescent’s risk of engaging in future suicidal behavior. Developing ways of classifying the form and pattern of suicide ideation may provide information to clinicians about an adolescent’s risk of making a suicide attempt and guide clinical care of adolescents.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Adolescence is a time of life during which suicidal thoughts and behaviors tend to emerge and have their highest prevalence, relative to adulthood. In the United States, the 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts among high-school students rose from about 6% in 2009 to about 9% in 2019 (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). This compares to a 12-month prevalence of 1–2% among 18–25-year-olds and 0.3–0.4% among adults ages 26 and older within the same time period (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). However, because many more adolescents attempt suicide than die by suicide, suicide deaths are difficult to predict in this age group. Psychological autopsy studies of adolescent suicides are limited and were conducted decades ago. However, evidence from these studies suggests that over half of adolescents who die by suicide may do so at their first attempt (Brent et al., 1999; Shaffer et al., 1996), making prediction of suicide deaths from previous suicide attempts difficult in adolescence. Difficulty predicting short-term risk of suicide with traditional clinical predictors has prompted researchers to develop alternative methods of predicting suicide risk, including the development of implicit measures (Cha et al., 2010; Nock et al., 2010; Tello et al., 2020), real-time and passive monitoring methods (Allen et al., 2019; Kleiman et al., 2019a), and the use of machine learning algorithms (Linthicum et al., 2019; Walsh et al., 2018).

While these are promising research avenues, we would like to suggest that one critical gap in knowledge that has prevented researchers and clinicians from being able to predict adolescent suicidal behavior is having a limited understanding of suicide ideation, defined as “thinking about, considering, or planning for suicide” (Crosby et al., 2011, p. 11). In a recent editorial, Jobes and Joiner (2019) argued that “...In our singular pursuit to prevent suicide deaths, we need to stop trivializing the obvious and vital importance of attending to suicidal ideation” (p. 229). Gaining a better understanding of suicide ideation, whose 12-month prevalence among US high-school students was about 19% in 2019 (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020), is an important step in assessing risk among adolescents. This is especially important, given research suggesting that first-time suicide attempts occur within 1 year after the onset of suicide ideation (Nock et al., 2013). Contemporary theories of suicide focus on factors that lead to the development of suicide ideation, and there has been a push over the last decade to move beyond predicting suicide ideation to understanding the transition to suicide attempts (Glenn & Nock, 2014). Furthermore, the proposed Suicidal Behavior Disorder in the DSM-5 focuses exclusively on suicide attempts and does not include suicide ideation among its diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), missing a potential opportunity to understand the phenomenology of the thoughts preceding suicidal behavior. Other proposed syndromes aimed at capturing imminent risk, such as Suicide Crisis Syndrome and Acute Suicidal Affective Disturbance (Galynker, 2017; Rogers et al., 2017; Stanley et al., 2016), focus primarily on other criteria (e.g., entrapment, arousal, social alienation), and while they do consider increases in suicidal intent, they do not elaborate on the features of suicide ideation that might be informative about risk.

There is no theory, of which we are aware, that has sought to tackle understanding suicide ideation, itself, nor how suicide ideation might change the nature of risk for suicide attempts. Furthermore, many prevailing psychological models of suicide focus on adults and ignore adolescence, the time of life when rates of suicide ideation increase (Boeninger et al., 2010; Bolger et al., 1989; Borges et al., 2008b; Kessler et al., 1999; Nock et al., 2013). In this chapter, we present a case for the importance of understanding the form and patterns of suicide ideation. We begin with a review of what some contemporary theories of suicide suggest about suicide ideation and address their limitations. We follow with research that is informative about the characteristics of suicide ideation, in terms of its form and patterns. Next, we describe evidence of different suicide ideation trajectories from prospective and ecological momentary assessment studies. Finally, we conclude with a proposed model of classification of subtypes of suicide ideation that can inform and guide clinical assessment, and we discuss clinical implications of these suicide ideation subtypes.

What Some Theories of Suicide Suggest About Suicide Ideation

Some contemporary psychological theories of suicide suggest that understanding the form that suicide ideation takes is important. For instance, the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide suggests that suicide risk is a function of both capability for suicide and suicidal desire (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). While suicidal desire—i.e., how much a person wishes to die—depends on whether people perceive themselves as a burden to others (perceived burdensomeness) and whether they do not feel that they belong to a group (thwarted belongingness), whether people have the ability to engage in lethal self-harm depends on their lowered fear of death and elevated tolerance for physical pain. The model suggests that people lower their fear of death through experiences, such as previous self-harm or suicide attempts, that habituate them to the idea of lethal self-harm. This can include detailed suicide-related mental simulation. Thus, the Interpersonal Theory would suggest that it is not only whether people think about suicide that matters, but how they think about suicide that might also contribute to the capability for suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Much of the research testing the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide either focuses on the circumstances that lead to suicide ideation (e.g., examining perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belonging as predictors of suicide ideation) or on the relationship between capability for suicide and suicidal behavior (see Chu et al., 2017, for a systematic review and meta-analysis). However, the ways in which the form that suicide ideation takes (e.g., how often people think about killing themselves, how vivid their thoughts are, how long they last, and how much difficulty they have disengaging from their thoughts) might also give rise to the capability for suicide has been neglected.

Like the Interpersonal Theory, Rudd’s Fluid Vulnerability Theory distinguishes between acute and chronic suicide risk. Acute risk lasts only as long as a particular suicidal episode. However, chronic risk is underlying and is influenced by such factors as previous suicide attempt history, with individuals who have engaged in multiple previous suicide attempts having higher chronic risk of engaging in future suicidal behavior than individuals with no previous suicide attempt history or compared to individuals with only one previous suicide attempt. Drawing upon Beck’s theory of modes (Beck, 1996), which suggests a connection in memory between suicide-related thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and motives, the fluid vulnerability theory suggests that each suicidal episode lowers the threshold for triggering future episodes, because it strengthens the connections between the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that surrounded previous suicidal episodes (Rudd, 2000, 2006). Thus, repeated suicide ideation would continually strengthen the connections in memory between aspects of the suicidal mode, ultimately increasing chronic risk of making a suicide attempt.

The cognitive model of suicide (Wenzel & Beck, 2008) centers on the role of maladaptive cognition in facilitating the transition to suicidal behavior. Like the fluid vulnerability theory, the cognitive model suggests that trait-like vulnerability factors contribute to chronic risk for psychiatric disturbance, in general. Then in the presence of elevated life stress, these general cognitive processes may activate suicide-specific cognitive processes. Cognitive processes in this theory refer to both the content and form, or process, of thinking—that is, what people think about and how they think about it (e.g., information processing biases). Specifically, the theory proposes that the greater the frequency, intensity, or duration of cognitive processes associated with psychiatric disturbance, the greater the likelihood of activating a suicide schema. A schema is defined as a mode of thinking that helps people organize information in a meaningful way (Clark & Beck, 1999). When a suicide schema is activated, according to the theory, it facilitates biased information processing in such a way that suicide-specific cognitions and cognitive processes are given preference. Two such processes are attentional biases toward suicide-relevant cues and attentional fixation, a narrowing of attention and preoccupation with suicide as the only solution. These processes together, along with state hopelessness, exacerbate suicide ideation and culminate into suicidal behavior at the point when the individual cannot tolerate distress any longer (Wenzel & Beck, 2008).

Taken together, these theories suggest that repeated suicide ideation, over time, would increase a person’s underlying risk for engaging in future suicidal behavior by biasing attention to suicide-related stimuli, and perhaps fixating attention on suicide-related stimuli, reinforcing suicide-related schemas, lowering the threshold for triggering future suicidal episodes, and ultimately increasing the capability for suicide.

Role of Attention Bias and Engagement/Disengagement

The cognitive model of suicidal behavior suggests an important role of attention bias toward suicide-related stimuli and attentional fixation on suicide in conferring vulnerability to making a suicide attempt (Wenzel & Beck, 2008). Past and recent research has provided some support for this idea, mainly in research that has made use of an adapted form of the Stroop Task to measure attention bias toward suicide-related stimuli among adults with differing histories of suicidal behavior. The classic Stroop task (Stroop, 1935) is a color-naming task in which there is either congruence or incongruence between the semantic content of a word and the color in which the word is printed (e.g., the word “green” printed in green ink vs. the word “green” printed in blue ink). The speed and accuracy with which people perform the color-naming task are used as a measure of people’s ability to inhibit the cognitive interference from the semantic content of the words in the incongruent trials, but it is also used as a measure of attention. The Emotional Stroop Task (Cisler et al., 2011; Dobson & Dozois, 2004; Epp et al., 2012) and the Suicide Stroop task (Cha et al., 2010) are modified versions of the classic Stroop task. Instead of using names of colors as word stimuli, the emotional Stroop task uses different categories of valenced stimuli to detect “attentional biases” specific to relevant psychopathologies (e.g., depression-related or anxiety-related words). The Suicide Stroop task is a modified version of the Emotional Stroop task and uses suicide- and death-relevant stimuli to detect suicide-specific attentional biases, rather than a general attentional bias toward negative stimuli. Attention bias is indicated by a person’s average response latency to respond to suicide-related words relative to neutral words (see Cha et al., 2010, for details).

A meta-analysis of four studies examining suicide-specific attentional processing using the Suicide Stroop found a small effect for suicide-specific interference for adults with suicide attempt histories (Richard-Devantoy et al., 2016). In contrast, there was no interference effect for negative stimuli, suggesting specificity to suicide-related cognitions. We highlight that none of the studies examined these relationships in children or adolescents, and only one of the studies in the meta-analysis focused on emerging adults (Chung & Jeglic, 2016). The findings using the Suicide Stroop have been generally consistent, though the methodologies and analyses have varied between studies. For instance, Cha et al. (2010) found that adults with a suicide attempt history exhibited greater suicide-specific interference than interference from negative stimuli (relative to neutral); further, adults with recent suicide attempts demonstrated greater suicide-specific interference than adults with more distal suicide attempts. Importantly, this attentional interference predicted suicide attempts within 6 months. Two other studies found that adults with a suicide attempt history exhibited longer latencies in responding to suicide-specific stimuli (see Becker et al., 1999; Williams & Broadbent, 1986).

A more recent study of adult patients used both a classic Stroop and an Emotional Stroop Task to identify differences in Stroop interference between patients with high and low risk for suicide ideation and attempts (Thompson & Ong, 2018). Findings revealed a strong Stroop effect for the classic Stroop task, such that the high-risk group was less accurate and responded more slowly. In contrast, participants responded more quickly to all emotional stimuli when engaging in the Emotional Stroop task, with no Stroop effect occurring. Still, the high-risk group took longer to respond to the word “suicide,” replicating previous findings from a college-student sample (Chung & Jeglic, 2016).

Although the Suicide Stroop has been used as a proxy for attentional processing and thereby attentional bias relevant to suicidal cognitions, a recent psychometric study that analyzed data from seven separate studies, with participants ranging in age from 12 to 81 years, found that the most common scoring approach for the Suicide Stroop had low internal consistency reliability. In addition, it performed no better than chance in classifying individuals with versus without a suicide attempt history (Wilson et al., 2019) thus not replicating one of the previous Suicide Stroop findings (Cha et al., 2010). This low reliability potentially undermines conclusions drawn from previous work and recent attempts to develop interventions to shift suicide-specific attention bias. For instance, a study that used an attention bias modification task to reduce severity of suicide ideation and suicide-specific attentional bias among a community and clinical sample found no effect in shifting these cognitive processes. The authors suggested that the duration and implementation of the bias modification task may not have been adequate to obtain the desired effects (Cha et al., 2017). However, another possibility is that the task was targeting the wrong attentional process. A major limitation with the Suicide Stroop is that it is unclear whether it measures how long it takes to focus attention on suicide-related stimuli (engagement) versus how long it takes to remove attention after the person has attended to a stimulus (disengagement), or whether it does, in fact, measure attention bias at all (versus cognitive/semantic interference). Prior to developing suicide-related attention bias modification interventions, it is important to understand which suicide-specific attentional processes are associated with suicide ideation and confer risk of suicide attempts.

Recent work has begun to distinguish between these attentional processes in relation to suicide-specific biases. One study used Posner’s spatial cueing paradigm (Posner, 1980) to measure both attention engagement and disengagement. In this spatial cuing task, participants view a cueing word (e.g., suicide-related, negatively valenced) followed by a cueing probe. Congruent trials present both the cueing word and the cueing probe in the same visual field, whereas incongruent trials present them in opposite visual fields. Congruent trials measure attention engagement, while incongruent trials measure attention disengagement. The results indicated that depressed patients high in suicidal behavior (determined via median split of scores on a measure assessing suicide ideation and attempt history) more easily disengaged from suicide-related stimuli, relative to neutral stimuli, even when taking into account their symptoms of anxiety and depression (Baik et al., 2018). It is possible that adults with more experiences of suicide ideation and attempts have developed greater automaticity in processing suicide-specific content.

There is limited work examining suicide-related attention bias among children and adolescents. One study examining attentional bias toward fearful, sad, and happy faces found that children with previous suicide ideation sustained (i.e., focused) their attention on fearful faces longer than on sad or happy faces, relative to children without a history of suicide ideation (Tsypes et al., 2017). However, there was no difference in attention orienting (i.e., how long it took the children to initially focus their attention) on fearful, sad, or happy faces. Importantly, these findings were only captured through eye-tracking techniques, because there were no differences in attention orienting and sustained attention using reaction time methods, highlighting the need for sensitivity in multimethod approaches. Further work is needed to better disentangle specific attentional processing underlying the development and maintenance of suicide ideation, particularly among children and adolescents.

Limitations of Current Measurement of Suicide Ideation

Suicide ideation measures tend to either include a few items that screen for the presence of suicidal thoughts or scales that generate total scores indicating increasing degree or severity of ideation. However, there is no established cutoff score that indicates whether an adolescent is at risk of making a suicide attempt, nor does a total score provide specific information about the nature of the adolescent’s suicide ideation. Further, the ability of suicide ideation measures to predict whether adolescents will make a suicide attempt is mixed (Gipson et al., 2015; King et al., 1997, 2014; Prinstein et al., 2008), with research with clinical samples of adolescents suggesting that change in suicide ideation scores predict future suicide attempts (Prinstein et al., 2008), others finding this to be the case among adolescent girls but not among boys (King et al., 2014), and still others finding that scores on a measure of suicide ideation intensity do not predict future suicide attempts among adolescents presenting to an emergency department with suicide ideation (Gipson et al., 2015). Developing ways of classifying suicide ideation to provide information to clinicians about an adolescent’s risk of making a future suicide attempt may improve clinical care of adolescents who disclose suicide ideation or report thoughts about suicide on a screening questionnaire.

There is a dearth of research on characteristics of suicide ideation that predict future suicide attempts, overall, but particularly among adolescents. Established ways of assessing suicide ideation tend to focus on how strongly people wish to die, whether they have considered a method, and whether they engage in planning (Beck et al., 1997; Harriss & Hawton, 2005; Harriss et al., 2005; Joiner et al., 1997, 2003; Suominen et al., 2004; Witte et al., 2006). There is little information on whether such characteristics predict suicide attempts and suicide deaths among adolescents.

No measure of suicide ideation of which we are aware focuses on the form that suicide ideation takes—in terms of its frequency (i.e., the actual number of times it occurs on a given day or in a given week), duration (i.e., the actual number of minutes or hours it lasts), and pattern (i.e., the actual number of subsequent days it happens). Those that do inquire about these characteristics do so as part of summary scales not meant to focus on these elements of ideation. For example, the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2008) includes questions about frequency, duration, and controllability of ideation under a five-item suicide ideation “intensity” subscale that also includes reasons for ideation and the presence of deterrents to making a suicide attempt. The Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI ; Beck et al., 1979) captures frequency and duration of ideation under its “suicidal desire” subscale that also includes ratings of wish to die. The Suicide Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ-Jr.) (Reynolds, 1987) assesses how frequently adolescents have thoughts about being better off dead, wishing they were dead, of killing themselves, or of communicating their suicidal intent in the previous month on a scale ranging from “never” to “almost every day.” However, the measure does not inquire about how many times per day individuals think about suicide nor about how long the thoughts last. This is a limitation of current measures, because there is emerging evidence that the form of suicide ideation might be informative about an individual’s risk profile. A study of adolescents with a previous suicide attempt history found that in addition to having a serious wish to die, suicide planning lasting an hour or longer (vs. less than an hour) preceding the adolescent’s most recent suicide attempt (as assessed at baseline) predicted a reattempt during a 4–6-year follow-up period (Miranda et al., 2014a). Miranda et al. (2014b) found that among adolescents who endorsed suicide ideation in the previous 3–6 months, length of their most recent ideation predicted whether they went on to make a suicide attempt during a 4–6-year follow-up period, independently of wish to die, even adjusting for depressive symptoms and for history of a previous suicide attempt. Further, among those who attempted suicide within a follow-up period, length of a suicide ideation episode greater than an hour predicted earlier onset of a future attempt (within 1 year), relative to ideation length of less than an hour (within 3–4 years). Gipson et al. (2015) found that one question on the C-SSRS that inquired about duration of suicide ideation predicted a future suicide attempt among adolescents who presented to an emergency department with suicide ideation. However, other questions about frequency, controllability, deterrents, and reason for ideation were not associated with attempting suicide during a 12-month follow-up (Gipson et al., 2015). These findings suggest that knowing not only whether adolescents think about suicide but also how they do so—i.e., the form of their suicide ideation—is informative about their vulnerability to future suicidal behavior.

Suicide-Related Imagery

One understudied but potentially important characteristic of adolescent suicide ideation is the degree to which adolescents think about suicide in the form of verbal thoughts versus visual imagery. Research conducted with adolescents and young adults has examined the role of suicide-related imagery in distinguishing individuals with and without a history of a suicide attempt and in thus potentially conferring risk for future suicidal behavior. Building upon theories of mental imagery proposed by Beck (1971) and Lang (1979), Holmes and colleagues proposed that suicide-related imagery occurs in the form of “flash-forwards”—defined as “suicide-related mental images experienced during a crisis, including acting out future suicidal plans or being dead” (Holmes et al., 2007, p. 431; Hales et al., 2015). These images were considered akin to flashbacks experienced due to past trauma—but focused on the future rather than the past. In a study of 15 adults from the United Kingdom (UK) with a history of major depression and suicide ideation, Holmes and colleagues found that 13 out of 15 participants who were asked to describe their suicide-related cognitions during their “worst point” suicide ideation reported suicide-related images about the future, and two participants reported suicide-related images about the past. These images tended to be rich in detail. Two out of nine categories of thoughts—planning for a suicide attempt and thinking about what might happen if they died—were more often endorsed as containing imagery than verbal thoughts, while other categories (e.g., what might happen to other people if the person died) were equally reported as verbal thoughts versus imagery (Holmes et al., 2007). Other studies with small samples of adults from the UK with depression or bipolar disorder found similar results (Crane et al., 2012; Hales et al., 2011). In addition, Crane and colleagues found that severity of worst-point suicide ideation was associated with lower levels of distress and higher levels of comfort from the suicidal imagery (Crane et al., 2012), supporting the idea that suicidal imagery might lead to habituation to the idea of suicide, as would be predicted by the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010).

Additional research with adults has found differences in suicide-related imagery depending on the recency of suicide ideation or lifetime suicide attempt history in nonclinical samples. For instance, a study of 82 adults in Hong Kong with current suicide ideation, identified from an epidemiological sample, found that over one-third of these individuals reported imagery that was assessed by independent raters as being suicide-related, and over half of these images were about what would happen after the suicide. Individuals who reported suicide-related imagery had more severe suicide ideation than those without imagery at baseline but not at a 7-week follow-up (Ng et al., 2016). A study of 237 college undergraduates from the South-Central United States found that total score on a measure of overall frequency and severity of lifetime self-harm behavior, as assessed by the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (Gutierrez et al., 2001), was associated with greater suicide-related imagery. Furthermore, among 84 participants with a history of suicide ideation or attempts, 85% reported suicide-related imagery, and self-reported vividness of suicide-related imagery was associated with overall frequency and severity of self-harm (Holaday & Brausch, 2015). Finally, a study of 39 college undergraduates from the Northeastern United States who reported a lifetime history of suicide ideation found that reporting a higher degree of suicide-related mental imagery was associated with over two-and-a-half times higher odds of reporting a lifetime history of a suicidal plan or a suicide attempt (Lawrence et al., 2021b). Thus, studies with nonclinical samples of adults suggest that the presence of lifetime suicide-related imagery is relatively common among individuals with a history of suicide ideation or behavior and is associated with greater severity of their lifetime suicidal thoughts or behavior.

Thus far, there is only one published study of which we are aware that examined suicide-related imagery among adolescents. A study of 159 racially and gender-diverse adolescent inpatients from the Northeastern United States, 102 of whom had a lifetime history of suicidal thoughts, found that about 64% of adolescents with a history of suicidal thoughts reported a lifetime history of suicidal mental imagery. Furthermore, adolescents who reported suicidal mental imagery had 2.4 times higher odds of reporting that they had previously made a suicide attempt, compared to those without suicidal mental imagery, adjusting for demographic variables, history of non-suicidal self-injury, and history of suicidal verbal thoughts (Lawrence et al., 2021a). This is consistent with findings from our recent studies examining the process and content of suicide ideation among predominantly Hispanic/Latinx samples of adolescents from New York City presenting with recent suicide ideation or a suicide attempt and who were interviewed about their most recent suicide ideation (Miranda et al., 2021a, 2021b). About three-quarters of adolescents reported that their suicide ideation occurred in the form of mental imagery. In contrast to Lawrence et al.’s study, there was no difference between adolescents with and without a suicide attempt history in whether they reported mental imagery during their most recent suicide ideation. Our study differed demographically, clinically, and methodologically from that of Lawrence et al. (2021a). One difference was that we interviewed adolescents—all of whom presented with either suicide ideation or an attempt—about their recent suicide ideation/attempt, while about two-thirds of Lawrence et al.’s (2021a) sample had a lifetime history of suicide-related cognitions, and the researchers inquired about lifetime (rather than recent) suicide-related imagery. Collectively, however, research with both adults and adolescents seems to suggest that suicide-related imagery is common among clinical samples of individuals with a history of suicide ideation and that it should be studied further as a potential marker of risk for suicidal behavior.

Suicide Ideation Trajectories

Traditionally, studies have defined different patterns of suicide ideation based on instances in which an individual reported the presence of suicide ideation over different times of assessment. These trajectories include no suicide ideation, one-time ideation, and persistent ideation, in which suicide ideation is reported during more than one assessment point (Borges et al., 2008a; Have et al., 2009; Kerr et al., 2008; Ortin et al., 2019; Steinhausen & Winkler Metzke, 2004). The persistent pattern of ideation has been found to be associated with a higher risk of attempting suicide, compared to one-time suicide ideation or no ideation, in adult (Wilcox et al., 2010) and adolescent samples (Vander Stoep et al., 2011). One limitation of this traditional approach is that it does not capture change in the nature or severity of suicidal thoughts.

More recent studies with community and clinical samples of adolescents that have measured suicide ideation as a continuous variable over at least three time periods of assessment have identified three trajectories of suicide ideation. These trajectories include (1) persistently high; (2) persistently low; and (3) declining (suicide ideation that begins high and then decreases) or persistently moderate suicide ideation (Adrian et al., 2016; Czyz & King, 2015; Rueter et al., 2008; Wolff et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019), with trajectory names varying by study and with some studies finding sex differences in trajectories (Adrian et al., 2016; Reuter et al., 2008). A few of these studies have further examined how different suicide ideation trajectories predict risk of future suicide attempts and found that those adolescents whose suicide ideation was classified in the persistently high trajectory were more likely to attempt suicide in the future than those classified in the persistently low (Czyz & King, 2015; Rueter et al., 2008) or declining suicide ideation trajectory (Wolff et al., 2018). Thus, understanding how adolescents’ suicide ideation changes over time may help predict the risk of future suicidal behavior.

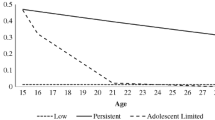

Research that has examined trajectories of suicide ideation from adolescence to adulthood or suicide ideation trajectories among adults have yielded slightly different findings. Erasquin et al. (2019) examined trajectories from adolescence to adulthood (ages 12–31 years) with a dichotomous measure of suicide ideation (i.e., presence/absence of suicide ideation in the previous year) and identified three trajectories of suicide ideation: sustained higher risk (i.e., suicide ideation consistently present from adolescence to adulthood), sustained lower risk (i.e., few suicidal thoughts from adolescence to adulthood), and adolescent-limited risk (i.e., presence of suicidal thoughts limited to ages 12–19) (Erausquin et al., 2019). Studies examining suicide ideation trajectories with adults, primarily among inpatient or military samples, have usually identified four trajectories of suicide ideation (Allan et al., 2019; Kasckow et al., 2016; Köhler-Forsberg et al., 2017; Madsen et al., 2016). Three of these trajectories are low-stable, moderate-stable, and high-stable suicide ideation, with the fourth trajectory varying across studies (e.g., high-declining, moderate-unstable, high-increasing). This discrepancy between studies with adolescents and adults suggests that suicide ideation profiles may vary by developmental period.

In sum, data from longitudinal studies suggest that temporal patterns of suicide ideation matter, in terms of predicting risk for future suicide attempts. These findings support the value of conceptualizing suicide ideation as a complex dynamic phenomenon.

Moment-to-Moment Variability in Suicide Ideation: Data from Ecological Momentary Assessment Studies

Studies examining change in suicide ideation over time have tended to rely on retrospective self-report measures and lengthy gaps between assessment follow-ups in longitudinal designs, with an average time between assessments of about 7 years (Ribeiro et al., 2016). Such gaps in measurement time points make it difficult to understand moment-to-moment variability in suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Glenn & Nock, 2014). To overcome these limitations, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods use smartphones, tablets, computers, and/or wearable devices to measure day-to-day changes in suicide ideation and risk of suicide attempts (Glenn & Nock, 2014; Nock et al., 2009; Shiffman et al., 2008). EMA involves frequent and repeated measurement of people’s experiences, feelings, and physiological responses as they naturally occur outside of a clinical or laboratory setting, to decrease recall bias and to increase reliability and ecological validity (Kleiman & Nock, 2018; Shiffman et al., 2008).

EMA studies of clinical samples of suicidal adults have found fluctuation of suicide ideation within very short time intervals (Forkmann et al., 2018; Hallensleben et al., 2019; Husky et al., 2017; Kleiman et al., 2017, 2018; Nock et al., 2009; Peters et al., 2020; Spangenberg et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). For example, Kleiman et al. (2017) queried participants about their suicidal desire, suicidal intent, and ability to resist their suicidal urges every 4–8 h over a period of 28 days and found that 94–100% of participants displayed high variability (change of more than one standard deviation over previous responses) in suicide ideation on most days. Furthermore, factors such as hopelessness, burdensomeness, and loneliness, which also showed high variability, were correlated with suicide ideation but did not predict short-term change (i.e., within 4–8 h) in suicide ideation (Kleiman et al., 2017). Other studies have found similar results within clinical samples of adults (Forkmann et al., 2018; Hallensleben et al., 2019; Husky et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2020; Spangenberg et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). In a 28-day EMA study of 51 adults with recent suicide ideation or attempts, Kleiman et al. (2018) used a latent profile analysis approach to identify five distinct phenotypes, or subtypes, of suicide ideation and found that those with a higher mean and lower variability around the mean (i.e., more severe and persistent suicide ideation) were more likely to have made a recent suicide attempt (Kleiman et al., 2018). Furthermore, one study of 83 adults found that variability in suicide ideation, assessed via EMA, improved prediction of short-term risk of a suicide attempt within a month of discharge from a hospital, beyond baseline admission data (Wang et al., 2021).

Several studies have suggested that EMA monitoring of suicidal thoughts and behavior is feasible and acceptable among adolescents (Czyz et al., 2018; Glenn et al., 2020; Kleiman et al., 2019b). Of the few existing studies examining short-term variability and prediction of suicide ideation and attempts among high-risk adolescents, most have produced similar findings to those conducted with clinical adult samples (Czyz et al., 2019, 2020). For example, a study of 34 adolescents hospitalized with recent suicide ideation or a suicide attempt (N = 34), assessed once per day over 28 days post-discharge, found that suicide ideation, as well as known correlates of suicide ideation (i.e., hopelessness, burdensomeness, and connectedness), varied considerably from day-to-day (Czyz et al., 2019). This research suggests that EMA can capture changes in suicide ideation potentially missed by longitudinal studies that conduct assessments over longer periods of time. Furthermore, a recent proof-of-concept study of 32 adolescents discharged from a hospital found that the combination of mean and variance of hopelessness, self-efficacy, and duration of suicide ideation, assessed via daily diary over an initial 2 weeks, predicted the occurrence of a suicide-related event (either rehospitalization or a suicide attempt) 2 weeks later (Czyz et al., 2020). It remains to be seen whether different profiles of suicide ideation, assessed via EMA, predict future suicidal behavior among adolescents.

Despite the feasibility and potential for fine-grained measurement of variability in suicide ideation, there are limitations to EMA approaches. One of these is compliance. Two recent studies found compliance rates to be approximately 65% for each momentary assessment among samples of adults presenting with suicide ideation (Kleiman et al., 2017; Porras-Segovia et al., 2020). A recent study of 53 adolescents found an EMA adherence rate of about 63%, with significantly lower adherence among racial and ethnic minoritized adolescents (40%), compared to White adolescents (69%) (Glenn et al., 2020). Factors that impact EMA compliance/adherence include study duration, number of assessments per day, compensation/incentives, and participant fatigue or burden (Ballard et al., 2021; Kleiman et al., 2017; Porras-Segovia et al., 2020). Furthermore, in studies using real-time monitoring, a standing issue that remains is how to keep participants at imminent risk of suicidal behavior safe (Kleiman et al., 2019a). Even while considering these limitations, EMA and real-time monitoring might help researchers better understand fluctuations in suicidal thoughts and behaviors, protective factors, and risk factors that might be missed by traditional approaches and measures (Ballard et al., 2021).

Suicide Ideation Subtypes

Collectively, longitudinal and EMA studies suggest that suicide ideation varies over the long- and short-term, with different risk profiles depending on a person’s pattern of suicide ideation. This research has highlighted the importance of tracking change in suicide ideation to potentially identify subgroups of individuals at risk of making a suicide attempt. However, some adolescents who come to the attention of a clinician may only be seen on one occasion, and there may not be opportunities to conduct multiple assessments of their ideation to identify a specific suicide ideation pattern. In those cases, it would be useful to develop ways of classifying adolescents’ suicide ideation during an initial assessment to inform decision-making, and perhaps supplement those classifications with information from subsequently available assessments.

One profile or subtype of adolescent suicide ideation suggested by both longitudinal and EMA studies is persistently elevated suicide ideation. Several studies involving follow-up of adolescents over 6 months to 1 year suggest that suicide ideation that remains persistently elevated is associated with increased risk of a suicide attempt during follow-up, compared to ideation that starts off elevated but declines or ideation that remains at subclinical levels (Czyz & King, 2015; Wolff et al., 2018). Furthermore, of the five suicide ideation subtypes identified in Kleiman et al.’s (2018) EMA study of adults, suicide ideation that was more persistently elevated was most strongly associated with having made a recent suicide attempt. There have been no comparable published studies, of which we are aware, identifying subtypes of adolescent suicide ideation via EMA, nor whether these subtypes prospectively predict future suicidal behavior. However, the limited evidence suggests a stronger association between a pattern of persistently elevated suicide ideation and suicide attempt risk.

Additional cross-sectional research with adults has also suggested different patterns of suicide ideation among adults who attempt suicide. A study of individuals, ages 18–64, who presented to a hospital within 24 h of a suicide attempt, found that suicide attempts that were preceded by 3 or more hours of suicide planning were less often triggered by a negative life event, compared to adults whose suicide attempts were preceded by less than 3 h of planning (Bagge et al., 2013). This finding suggests that whether negative life events precipitate an attempt depends on the nature of the suicide ideation preceding an attempt.

In a related vein, researchers have suggested two potential pathways of suicide risk involving differences in response to precipitating events, based on research with adolescents and adults. A study of a racially and ethnically diverse sample of 130 adolescents admitted to a hospital for a self-injurious threat, suicide ideation, or a suicide attempt found that adolescents whose suicidal crises were not preceded by a precipitating event had higher depressive symptoms, lower perceived problem solving, higher suicidal intent, and were more likely to have a history of a previous suicide attempt, compared to those whose suicidal crises were preceded by a precipitating event in the week before the crisis. The authors suggested that these findings reflected two potential pathways of risk: a non-stress-reactive pathway that might occur in the context of a depressive episode and a prior history of a suicide attempt and reflecting a longer, more gradual accumulation of risk; and a stress-reactive pathway involving brief escalation of a suicidal crisis and involving fewer suicidal plans and preparations (Hill et al., 2012). Bernanke et al. (2017) also proposed two subtypes of suicide attempts in adults—one involving acute responsiveness to stress and another involving non-stress-reactive suicide attempts. They propose that the former is associated with a history of trauma and involves suicide ideation that fluctuates in response to stressors, while the latter is associated with serotonergic dysfunction and depressive symptoms and involves persistent suicide ideation that does not fluctuate. A study of 35 adults with Major Depressive Disorder found that those classified as having brief suicide ideation, based on an item on the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (Beck et al., 1979; Beck & Steer, 1991) assessing duration of ideation, showed greater cortisol response to a social-evaluative stressor (the Trier Social Stress Test; Kirschbaum et al., 1993), compared to healthy volunteers and also compared to those classified as having “long/continuous” ideation, suggesting greater stress reactivity among those with brief suicide ideation (Rizk et al., 2018). This classification was based on a single item characterizing suicide ideation over the previous week, rather than examining a more extended pattern of day-to-day ideation. Furthermore, this model focuses on suicide ideation in the context of a suicide attempt. It is unclear whether the model, developed with adults, would apply to adolescents with suicide ideation, or to adolescents without major depression and/or with suicide ideation but no history of suicide attempts. However, these findings suggest that different types or patterns of suicide ideation might have different profiles of risk, and supports the importance of going beyond examining the presence of suicide ideation or total scores on a suicide ideation measure in the assessment of suicide risk.

Current adolescent suicide risk assessments do not classify suicide ideation based on characteristics that might be informative about the risk of future suicide attempts. In order to fill this knowledge gap and encourage future research, we suggest, as a starting point, three broad categories of adolescent suicide ideation subtypes that we have observed in our ongoing research and that might be supported by previous studies—brief suicide ideation, intermittent suicide ideation, and persistent suicide ideation. We classify these adolescents using a semi-structured interview we developed that makes detailed inquiries about adolescents’ most recent suicide ideation (Miranda et al., 2021b). We theorize that persistent suicide ideation, which we classify as involving uninterrupted suicide ideation over at least a 2-week period, is associated with increased risk of a suicide attempt and with a shorter time-to-an-attempt, based on research suggesting that ideating for a longer period of time is associated with increased risk of a suicide attempt and with shorter time-to-an-attempt (Miranda et al., 2014b). This is the type of suicide ideation that might be precipitated by a sustained dysphoric mood, rather than a specific triggering event. It might be described by adolescents as always being present in the back of their minds (e.g., They might start thinking about wanting to die or about killing themselves as soon as they wake up in the morning, and these thoughts might continue at different points throughout the day). In contrast, we classify brief suicide ideation as lasting less than 2 weeks, whether interrupted or uninterrupted. Brief suicide ideation is the type of suicide ideation that tends to be precipitated by a particular event, such as an interpersonal conflict (e.g., argument with a parent, friend, or romantic partner), rather than being longer standing and not arising in response to an external precipitant. This type of suicide ideation might last from several minutes to several hours or days. Intermittent suicide ideation is similar to persistent suicide ideation, in that it is longer standing suicide ideation (lasting 2 weeks or more) but might be described as occurring “on and off.” See Table 9.1 for working definitions and descriptions of these proposed suicide ideation subtypes.

Based on contemporary models of suicide, we would expect that a persistent form of suicide ideation would be associated with increased accessibility of suicide-related cognitions (reflecting persistent activation of a suicide-related schema) and thus a lower threshold necessary to trigger a suicidal episode. The more adolescents think about suicide, the more that memories of previous suicide attempts might be activated, and the more that environmental cues available while an adolescent is thinking about suicide might become associated, in memory, with making a suicide attempt. In other words, persistent suicide ideation might continually trigger the suicide-related schemas used to organize the circumstances surrounding previous suicide attempts or suicidal thoughts in memory, in the same way that having a history of repeated previous suicide attempts is thought to lower the threshold for triggering future suicidal episodes by making the activation of a suicidal mode more likely (Rudd, 2000, 2006). If this is the case, adolescents with persistent suicide ideation may be more likely to consider suicide when faced with even minor stressors (e.g., perceived social slights) than adolescents with brief suicide ideation. Additional research is needed to examine these possibilities.

Limits of Direct Inquiries About Adolescent Suicide Ideation

Before discussing the implications of considering the form and pattern of suicide ideation in assessments of adolescents presenting for clinical care, we should note that despite efforts to better understand suicide ideation, and potentially use that information to improve risk assessments, there are limits to asking direct questions about suicide ideation. Some youth experiencing suicide ideation may not disclose their thoughts, and there is evidence that those with higher risk profiles are less likely to disclose their suicide ideation. One study of 990 adolescents, ages 14–17 years, found that among 74 adolescents who reported past suicidal behavior, 27 of these adolescents did not disclose their suicide attempt to parents or significant others, and those who did not disclose their ideation were characterized by higher levels of suicide ideation and perceived victimization, along with a lower willingness to talk to others about their problems (Levi-Belz et al., 2018). Another study of 527 young adults experiencing homelessness found that less than one-third of young adults disclosed their suicide ideation (Fulginiti et al., 2020). Similarly, a cross-national study in Europe found that adolescents who had previously disclosed their suicide ideation reported lower current ideation than those who had never disclosed (Eskin, 2003). In addition, research on self-disclosure has previously suggested that low self-disclosure is associated with higher suicide-related risk (Apter et al., 2001; Horesh & Apter, 2006). Finally, research with college students has suggested that racial and ethnic minority young adults are less likely to self-disclose their suicide ideation when seeking treatment, compared to White young adults (Morrison & Downey, 2000). Whether this translates to an unwillingness to disclose during a suicide risk assessment is unknown.

Clinical Implications

Existing interventions for suicidal youth focus primarily on reducing suicidal behavior. Little research exists on whether such interventions have the potential to reduce suicide ideation. For example, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is a leading evidence-based treatment for suicidal individuals, with evidence of efficacy in adolescents (McCauley et al., 2018). A recent meta-analysis, however, showed that while DBT significantly reduced suicidal behavior across studies, there was no statistically significant pooled effect of DBT on suicide ideation (see DeCou et al., 2019). Although these results may appear to suggest that DBT is less effective at reducing suicide ideation, perhaps the problem is that too few research studies assess suicide ideation, as even DBT prioritizes focus on suicidal behaviors rather than suicidal thoughts (Linehan, 1993).

How can a greater focus on suicide ideation influence prevention and intervention efforts? First, it can help us understand the scope of the problem and influence clinical assessment. A growing body of research suggests that different forms of suicide ideation differentially impact suicide risk. Persistent suicide ideation, in particular, may predict both greater risk of an attempt and shorter time to an attempt. Better documenting and understanding this link can lead to change in the practice of clinical assessment. Clinicians can start to classify adolescents who present with a brief, intermittent, or persistent profile of ideation—and each classification will then call for a different intervention.

Second, to arrive at more precise and effective interventions for suicide ideation, several questions need to be answered regarding the nature and function of specific types of suicide ideation. At what point does each subtype arise? What precipitates it? What function does it serve for the adolescent at the moment? Answering these questions will influence treatment of suicide ideation. For example, evidence suggests that brief ideation may be an outcome of stress reactivity, whereas persistent ideation may occur in the context of a sustained negative mood. If this is the case, clinical intervention for brief ideation might prioritize a focus on adaptive coping with stressful events ahead of time. In contrast, for persistent ideation, a mindfulness approach to strengthen the individual’s awareness of and ability to exit negative thought spirals as they arise may be more effective. The question regarding function of specific types of suicide ideation is also important. For example, if as some evidence suggests, suicide ideation that takes the form of imagery provides comfort during a suicidal crisis (Crane et al., 2012), alternatives can be found that provide similar benefits without conferring risk for suicidal behavior.

Equally importantly, understanding how form and characteristics of suicide ideation confer risk can improve treatment by leading to interventions that directly target those underlying mechanisms. For example, how might persistent ideation confer increased risk for an attempt? What is it, specifically, about persistent ideation that increases risk? The cognitive model of suicide, which serves as the conceptual framework for cognitive therapy for suicide attempts (Brown et al., 2005; Wenzel & Jager-Hyman, 2012), emphasizes the role of attentional biases in facilitating the transition to an attempt once a suicide-related schema has been activated (Wenzel & Beck, 2008). Persistent ideation may have different underlying mechanisms (e.g., attentional fixation) than other forms of ideation, in which case treatment might then prioritize strategies to ease disengagement from suicide ideation. Importantly, increasing adolescents’ own awareness of how exactly their thoughts function to perpetuate their own distress can motivate them to engage in the process of learning alternative strategies that reduce harm and provide relief—an endeavor that can only be achieved with greater research focus on the nature and consequences of different forms of suicide ideation.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have made a case for why a detailed assessment of suicide ideation is an important and understudied area of research. We have argued that addressing this gap in knowledge has the potential to improve prediction of adolescent suicidal behavior. We join other voices in the field who have called for a great focus on understanding and preventing suicide ideation just as much as we, as a field, have focused on understanding and preventing suicidal behavior (Jobes & Joiner, 2019). Meta-analytic evidence suggests that suicide ideation is the third strongest predictor of future suicide (Franklin et al., 2017); understanding the nature of suicide ideation and how its form and characteristics may confer risk for suicidal behavior can pave the way for improved prevention and interventions efforts.

References

Adrian, M., Miller, A. B., McCauley, E., & Vander Stoep, A. (2016). Suicidal ideation in early to middle adolescence: Sex-specific trajectories and predictors. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(5), 645–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12484

Allan, N. P., Gros, D. F., Lancaster, C. L., Saulnier, K. G., & Stecker, T. (2019). Heterogeneity in short-term suicidal ideation trajectories: Predictors of and projections to suicidal behavior. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 49(3), 826–837. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12480

Allen, N. B., Nelson, B. W., Brent, D., & Auerbach, R. P. (2019). Short-term prediction of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents: Can recent developments in technology and computational science provide a breakthrough? Journal of Affective Disorders, 250, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.044

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

Apter, A., Horesh, N., Gothelf, D., Graffi, H., & Lepkifker, E. (2001). Relationship between self-disclosure and serious suicidal behavior. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 42(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1053/comp.2001.19748

Bagge, C. L., Glenn, C. R., & Lee, H. J. (2013). Quantifying the impact of recent negative life events on suicide attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(2), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030371

Baik, S. Y., Jeong, M., Kim, H. S., & Lee, S. H. (2018). ERP investigation of attentional disengagement from suicide-relevant information in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.046

Ballard, E. D., Gilbert, J. R., Wusinich, C., & Zarate, C. A. J. (2021). New methods for assessing rapid changes in suicide risk. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, Article 598434. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.598434

Beck, A. T. (1971). Cognitive patterns in dreams and day dreams. In J. H. Masserman (Ed.), Dream dynamics: Science and psychoanalysis (pp. 2–7). Grune & Stratton.

Beck, A. T. (1996). Beyond belief: A theory of modes, personality, and psychopathology. In P. M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Frontiers of cognitive therapy (pp. 1–25). Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., Brown, G. K., & Steer, R. A. (1997). Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(11), 1039–1046. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00073-9

Beck, A. T., Kovacs, M., & Weissman, A. (1979). Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(2), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.343

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1991). Manual for Beck scale for suicide ideation. Psychological Corporation.

Becker, E. S., Strohbach, D., & Rinck, M. (1999). A specific attentional bias in suicide attempters. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(12), 730–735. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199912000-00004

Bernanke, J. A., Stanley, B. H., & Oquendo, M. A. (2017). Toward fine-grained phenotyping of suicidal behavior: The role of suicidal subtypes. Molecular Psychiatry, 22(8), 1080–1081. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.123

Boeninger, D. K., Masyn, K. E., Feldman, B. J., & Conger, R. D. (2010). Sex differences in developmental trends of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts among European American adolescents. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 40(5), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.5.451

Bolger, N., Downey, G., Walker, E., & Steininger, P. (1989). The onset of suicidal ideation in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 18(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02138799

Borges, G., Angst, J., Nock, M. K., Ruscio, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2008a). Risk factors for the incidence and persistence of suicide-related outcomes: A 10-year follow-up study using the National Comorbidity Surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders, 105(1–3), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.036

Borges, G., Benjet, C., Medina-Mora, M. E., Orozco, R., & Nock, M. (2008b). Suicide ideation, plan, and attempt in the Mexican adolescent mental health survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e31815896ad

Brent, D. A., Baugher, M., Bridge, J., Chen, T., & Chiappetta, L. (1999). Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(12), 1497–1505. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199912000-00010

Brown, G. K., Ten Have, T., Henriques, G. R., Xie, S. K., Hollander, J. E., & Beck, A. T. (2005). Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 294(5), 563–570. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.5.563

Cha, C. B., Najmi, S., Amir, N., Matthews, J. D., Deming, C. A., Glenn, J. J., Calixte, R. M., Harris, J. A., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Testing the efficacy of attention bias modification for suicidal thoughts: Findings from two experiments. Archives of Suicide Research, 21(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2016.1162241

Cha, C. B., Najmi, S., Park, J. M., Finn, C. T., & Nock, M. K. (2010). Attentional bias toward suicide-related stimuli predicts suicidal behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(3), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019710

Chu, C., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Tucker, R. P., Hagan, C. R., Rogers, M. L., Podlogar, M. C., Chiurliza, B., Ringer-Moberg, F. B., Michaels, M. S., Patros, C., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000123

Chung, Y., & Jeglic, E. L. (2016). Use of the modified emotional stroop task to detect suicidality in college population. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 46(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12174

Cisler, J. M., Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Adams, T. G., Babson, K. A., Badour, C. L., & Willems, J. L. (2011). The emotional Stroop task and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(5), 817–828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.007

Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (1999). Scientific foundations of cognitive theory and therapy of depression. Wiley.

Crane, C., Shah, D., Barnhofer, T., & Holmes, E. A. (2012). Suicidal imagery in a previously depressed community sample. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 19(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.741

Crosby, A. E., Ortega, L., & Melanson, C. (2011). Self-Directed Violence Surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements, Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/self-directed-violence-a.pdf

Czyz, E. K., Horwitz, A. G., Arango, A., & King, C. A. (2019). Short-term change and prediction of suicidal ideation among adolescents: A daily diary study following psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 60(7), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12974

Czyz, E. K., King, C. A., & Nahum-Shani, I. (2018). Ecological assessment of daily suicidal thoughts and attempts among suicidal teens after psychiatric hospitalization: Lessons about feasibility and acceptability. Psychiatry Research, 267, 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.031

Czyz, E. K., Yap, J. R. T., King, C. A., & Nahum-Shani, I. (2020). Using intensive longitudinal data to identify early predictors of suicide-related outcomes in high-risk adolescents: Practical and conceptual considerations. Assessment. Advance inline publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120939168

Czyz, E. K., & King, C. A. (2015). Longitudinal trajectories of suicidal ideation and subsequent suicide attempts among adolescent inpatients. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.836454

DeCou, C. R., Comtois, K. A., & Landes, S. J. (2019). Dialectical behavior therapy is effective for the treatment of suicidal behavior: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 50(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.009

Dobson, K. S., & Dozois, D. J. A. (2004). Attentional biases in eating disorders: A meta-analytic review of Stroop performance. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(8), 1001–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.004

Epp, A. M., Dobson, K. S., Dozois, D. J. A., & Frewen, P. A. (2012). A systematic meta-analysis of the Stroop task in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(4), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.005

Erausquin, J. T., McCoy, T. P., Bartlett, R., & Park, E. (2019). Trajectories of suicide ideation and attempts from early adolescence to mid-adulthood: Associations with race/ethnicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1796–1805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01074-3

Eskin, M. (2003). A cross-cultural investigation of the communication of suicidal intent in Swedish and Turkish adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.t01-1-00314

Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Fox, K. R., Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Huang, X., Musacchio, K. M., Jaroszewski, A. C., Chang, B. P., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 187–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000084

Forkmann, T., Spangenberg, L., Rath, D., Hallensleben, N., Hegerl, U., Kersting, A., & Glaesmer, H. (2018). Assessing suicidality in real time: A psychometric evaluation of self-report items for the assessment of suicidal ideation and its proximal risk factors using ecological momentary assessments. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(8), 758–769. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000381

Fulginiti, A., Hsu, H. T., Barman-Adhikari, A., Shelton, J., Petering, R., Santa Maria, D., Narendorf, S. C., Ferguson, K. M., & Bender, K. (2020). Few do and to few: Disclosure of suicidal thoughts in friendship networks of young adults experiencing homelessness. Archives of Suicide Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2020.1795018

Galynker, I. (2017). The suicidal crisis: Clinical guide to the assessment of imminent suicide risk. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190260859.001.0001

Gipson, P. Y., Agarwala, P., Opperman, K. J., Horwitz, A., & King, C. A. (2015). Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Predictive validity with adolescent psychiatric emergency patients. Pediatric Emergency Care, 31(2), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000225

Glenn, C. R., Kleiman, E. M., Kearns, J. C., Santee, A. C., Esposito, E. C., Conwell, Y., & Alpert-Gillis, L. J. (2020). Feasibility and acceptability of ecological momentary assessment with high-risk suicidal adolescents following acute psychiatric care. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1741377

Glenn, C. R., & Nock, M. K. (2014). Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3 Suppl 2), S176–S180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.004

Gutierrez, P. M., Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., & Kopper, B. A. (2001). Development and initial validation of the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 77(3), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_08

Hales, S., Blackwell, S. E., Di Simplicio, M., Iyadurai, L., Young, K., & Holmes, E. A. (2015). Imagery-based cognitive assessment. In G. P. Brown & D. A. Clark (Eds.), Assessment in cognitive therapy (pp. 69–93). Guilford Press.

Hales, S. A., Deeprose, C., Goodwin, G. M., & Holmes, E. A. (2011). Cognitions in bipolar affective disorder and unipolar depression: Imagining suicide. Bipolar Disorders, 13(7–8), 651–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00954.x

Hallensleben, N., Glaesmer, H., Forkmann, T., Rath, D., Strauss, M., Kersting, A., & Spangenberg, L. (2019). Predicting suicidal ideation by interpersonal variables, hopelessness and depression in real-time. An ecological momentary assessment study in psychiatric inpatients with depression. European Psychiatry, 56(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.003

Harriss, L., & Hawton, K. (2005). Suicidal intent in deliberate self-harm and the risk of suicide: The predictive power of the Suicide Intent Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders, 86(2–3), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.02.009

Harriss, L., Hawton, K., & Zahl, D. (2005). Value of measuring suicidal intent in the assessment of people attending hospital following self-poisoning or self-injury. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.1.60

Have, M. T., De Graaf, R., Van Dorsselaer, S., Verdurmen, J., Van't Land, H., Vollebergh, W., & Beekman, A. (2009). Incidence and course of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the general population. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(12), 824–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905401205

Hill, R. M., Pettit, J. W., Green, K. L., Morgan, S. T., & Schatte, D. J. (2012). Precipitating events in adolescent suicidal crises: Exploring stress-reactive and nonreactive risk profiles. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 42(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00067.x

Holaday, T. C., & Brausch, A. M. (2015). Suicidal imagery, history of suicidality, and acquired capability in young adults. Journal of Aggression, Conflict, and Peace Research, 7(3), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/JACPR-10-2014-0146

Holmes, E. A., Crane, C., Fennell, M. J. V., & Williams, J. M. G. (2007). Imagery about suicide in depression – “Flash-forwards”? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 38(4), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.004

Horesh, N., & Apter, A. (2006). Self-disclosure, depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Crisis, 27(2), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.27.2.66

Husky, M., Swendsen, J., Ionita, A., Jaussent, I., Genty, C., & Courtet, P. (2017). Predictors of daily life suicidal ideation in adults recently discharged after a serious suicide attempt: A pilot study. Psychiatry Research, 256, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.035

Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Demisse, Z., Crosby, A. E., Stone, D. M., Gaylor, E., Wilkins, N., Lowry, R., & Brown, M. (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a6

Jobes, D. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2019). Reflections on suicidal ideation. Crisis, 40(4), 227–230. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000615

Joiner, T. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

Joiner, T. E., Steer, R. A., Brown, G., Beck, A. T., Pettit, J. W., & Rudd, M. D. (2003). Worst-point suicidal plans: a dimension of suicidality predictive of past suicide attempts and eventual death by suicide. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(12), 1469–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(03)00070-6

Joiner, T. E., Rudd, M. D., & Rajab, M. H. (1997). The modified scale for suicidal ideation: Factors of suicidality and their relation to clinical and diagnostic variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(2), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.260

Kasckow, J., Youk, A., Anderson, S. J., Dew, M. A., Butters, M. A., Marron, M. M., Begley, A. E., Szanto, K., Dombrovski, A. Y., Mulsant, B. H., Lenze, E. J., & Reynolds, C. F., III. (2016). Trajectories of suicidal ideation in depressed older adults undergoing antidepressant treatment. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 73, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.11.004

Kerr, D. C., Owen, L. D., & Capaldi, D. M. (2008). Suicidal ideation and its recurrence in boys and men from early adolescence to early adulthood: An event history analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(3), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012588

Kessler, R. C., Borges, G., & Walters, E. E. (1999). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(7), 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617

King, C. A., Jiang, Q., Czyz, E. K., & Kerr, D. C. (2014). Suicidal ideation of psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents has one-year predictive validity for suicide attempts in girls only. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(3), 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9794-0

King, C. A., Hovey, J. D., Brand, E., & Ghaziuddin, N. (1997). Prediction of positive outcomes for adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(10), 1434–1442. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199710000-00026

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M., & Helhammer, D. H. (1993). The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’—A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28(1–2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000119004

Kleiman, E. M., Glenn, C. R., & Liu, R. T. (2019a). Real-time monitoring of suicide risk among adolescents: Potential barriers, possible solutions, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 48(6), 934–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1666400

Kleiman, E., Millner, A. J., Joyce, V. W., Nash, C. C., Buonopane, R. J., & Nock, M. K. (2019b). Using wearable physiological monitors with suicidal adolescent inpatients: Feasibility and acceptability study. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 7(9), Article e13725. https://doi.org/10.2196/13725

Kleiman, E. M., & Nock, M. K. (2018). Real-time assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Current Opinion on Psychology, 22, 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.026

Kleiman, E. M., Turner, B. J., Fedor, S., Beale, E. E., Huffman, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(6), 726–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000273

Kleiman, E. M., Turner, B. J., Fedor, S., Beale, E. E., Picard, R. W., Huffman, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2018). Digital phenotyping of suicidal thoughts. Depression and Anxiety, 35(7), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22730

Köhler-Forsberg, O., Madsen, T., Behrendt-Møller, I., Sylvia, L., Bowden, C. L., Gao, K., Bobo, W. V., Trivedi, M. H., Calabrese, J. R., Thase, M., Shelton, R. C., McInnis, M., Tohen, M., Ketter, T. A., Friedman, E. S., Deckersbach, T., McElroy, S. L., Reilly-Harrington, N. A., & Nierenberg, A. A. (2017). Trajectories of suicidal ideation over 6 months among 482 outpatients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.038

Lang, P. J. (1979). A bio-informational theory of emotional imagery. Psychophysiology, 16(6), 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1979.tb01511.x

Lawrence, H. R., Nesi, J., Burke, T. A., Liu, R. T., Spirito, A., Hunt, J., & Wolff, J. C. (2021a). Suicidal mental imagery in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(3), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00750-4

Lawrence, H. R., Nesi, J., & Schwartz-Mette, R. A. (2021b). Suicidal mental imagery: Investigating a novel marker of suicide risk. Emerging Adulthood. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968211001593

Levi-Belz, Y., Gavish-Marom, T., Barzilay, S., Apter, A., Carli, V., Hoven, C., Sarchiapone, M., & Wasserman, D. (2018). Psychosocial factors correlated with undisclosed suicide attempts to significant others: Findings from the adolescence SEYLE study. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 49(3), 759–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12475

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

Linthicum, K. P., Schafer, K. M., & Ribeiro, J. D. (2019). Machine learning in suicide science: Applications and ethics. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37(3), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2392

Madsen, T., Van Spijker, B., Karstoft, K. I., Nordentoft, M., & Kerkhof, A. J. (2016). Trajectories of suicidal ideation in people seeking web-based help for suicidality: Secondary analysis of a Dutch randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), Article e178. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5904

McCauley, E., Berk, M. S., Asarnow, J. R., Adrian, M., Cohen, J., Korslund, K., Avina, C., Hughes, J., Harned, M., Gallop, R., & Linehan, M. M. (2018). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 777–785. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109

Miranda, R., De Jaegere, E., Restifo, K., & Shaffer, D. (2014a). Longitudinal follow-up study of adolescents who report a suicide attempt: Aspects of suicidal behavior that increase risk of a future attempt. Depression and Anxiety, 31(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22194

Miranda, R., Ortin, A., Scott, M., & Shaffer, D. (2014b). Characteristics of suicidal ideation that predict the transition to future suicide attempts in adolescents. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(11), 1288–1296. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12245

Miranda, R., Ortin-Peralta, A., Macrynikola, N., Gallagher, M., Nahum, C., Mañaná, J., Rombola, C., Runes, S., & Waseem, M. (2021a). What do adolescents think about when they consider suicide? Implications for risk. Manuscript in preparation.

Miranda, R., Shaffer, D., Ortin Peralta, A., De Jaegere, E., Gallagher, M., & Polanco-Roman, L. (2021b). Adolescent Suicide Ideation Interview, version A. OSF Registries. https://osf.io/8j7b5

Morrison, L. L., & Downey, D. L. (2000). Racial differences in self-disclosure of suicidal ideation and reasons for living: Implications for training. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 6(4), 374–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.6.4.374

Nock, M. K., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., McLaughlin, K. A., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55

Nock, M. K., Park, J. M., Finn, C. T., Deliberto, T. L., Dour, H. J., & Banaji, M. (2010). Measuring the suicidal mind: Implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychological Science, 21(4), 511–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610364762

Nock, M. K., Prinstein, M. J., & Sterba, S. K. (2009). Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 816–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016948