Abstract

This chapter looks at the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on internal migrants in India. According to the 2011 Census, there are over 450 million internal migrants, of which a massive 54 million are inter-state migrants. A large number of these migrants consist of labourers who comprise a huge percentage of the informal sector workforce, both in the rural and urban areas of India, and are vital to the country’s economy. These workers are also some of the most vulnerable, with inadequacies in terms of working conditions and coverage of social safety nets, and are also largely absent from India’s policy discourses. This chapter highlights the size and extent of internal migration as well as its distribution across different states in India. It shows how the current crisis and lockdowns have affected their lives and livelihoods. It particularly looks at the responses of central and various state governments – at destinations and origins – to ensure migrants’ wellbeing. It also analyses the socioeconomic impact of the migrant exodus from major destinations and looks at solutions to enable and ensure that migration patterns in the future are sustainable, and more importantly, ensure migrants’ rights and dignity.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The pandemic has led to mass destabilisation of economies and societies across the world. The exponentially rising cases of infections around the globe prompted national lockdowns and near-blanket bans on the movement of people from one place to another. This has had major ramifications the work-life spectrum, but most notably on the lives of migrant workers, especially in India.

In the wake of India’s 25 March 2020 decision to impose a national lockdown, domestic migrants took desperate measures to reach home amid the pandemic and policies taken to contain it, at both the central and state levels. Migrants’ often long treks home were made in the most inhospitable of conditions, frequently with tragic results (Rajan et al., 2020a, b). In the end, we witnessed what some observers describe as ‘the largest movement of migrants since the partition’ (Ellis-Petersen & Chaurasia, 2020).

This chapter examines how the pandemic affected the lives and livelihoods of migrants in India. In doing so, we also critically examine the response of the governments at the central and state levels, thereby providing insights into how we can avoid such a dire situation in the future. In order to understand how these events came to pass, it is important to comprehend the size of the internal migrant population in India.

2 Internal Migration in India: Size and Characteristics

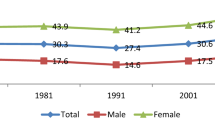

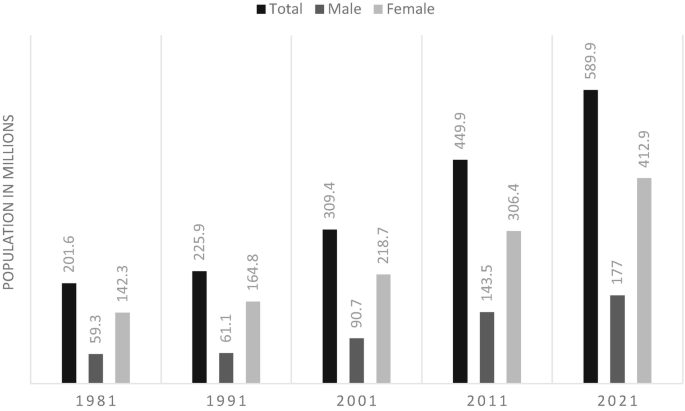

Migration within India has been a prevalent phenomenon throughout its history (Tumbe, 2018). The 2011 Census enumerated a staggering 450 million Indians as migrants based on place of last residence – a number representing 37% of the total population. In 2001, their number was at 309 million, with about 140 million added during 2001–2011 (Rajan, 2013). In the absence of a reliable estimate until the 2021 Census, we estimate a migrant population of 600 million persons (Fig. 12.1)Footnote 1 Based on the 2011 Census, around one-third of all internal migrants are inter-state and inter-district migrants, which makes them a population of almost 200 million. Of these 200 million inter-state and inter-district migrants, two-thirds are workers. This gives us an estimated migrant worker population of about 140 million today (Gupta, 2020). If we include intra-district migrant workers, the total number of migrant workers touches 200 million, excluding temporary and circular migrants (Bhagat et al., 2020). These migrant workers represent a range of occupations in both urban and rural milieus but are mainly concentrated in temporary, informal, and casual employment and are most vulnerable to exploitation (Keshri & Bhagat, 2013).

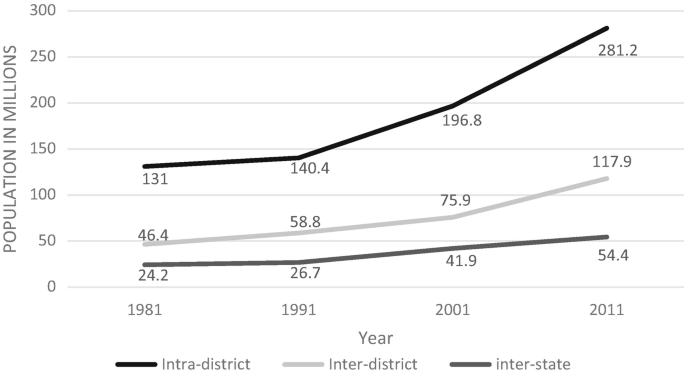

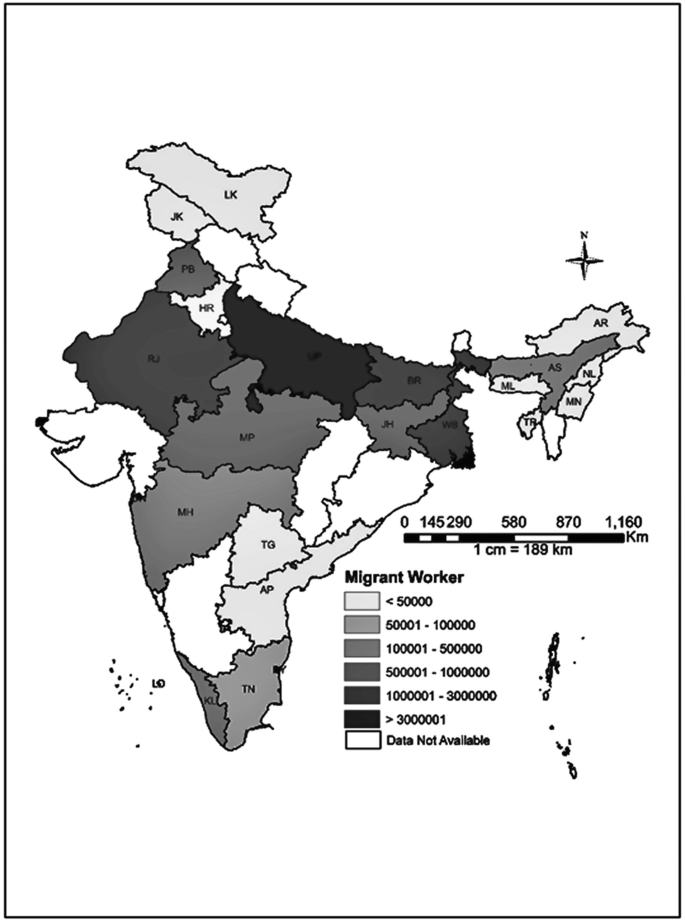

While India’s internal migrants totalled 450 million, the majority are short-distance inter-district migrants within states (Fig. 12.2). As per the 2011 Census, there were 117.9 million inter-district migrants and 54.4 million inter-state migrants in India.

Kone et al. (2018) note that the proportion of long-distance inter-state migration in India is low compared to other developing countries such as Brazil and China. This is despite the fact that, unlike in China under the hukou system, there are no separate restrictive measures for internal migrants at their destinations. This is due mainly to the non-portability of social welfare schemes such as the Public Distribution System (PDS) for subsidised food grain upon which millions of families are dependent and the requirement of state domicile for government jobs – which makes employment-based migration for a large cohort of the employable population challenging. Additionally, migration costs form a large barrier for most migrants to engage in long distance migration between states in India. This becomes extremely important, as there is an increase in the incidence of migration of families instead of individuals.

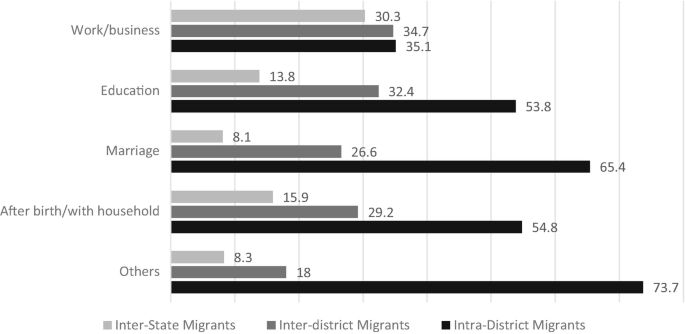

While most migration occurs within the district for work and employment reasons, other categories of migration happen for education, marriage, and household movement, which are more intra-district in nature (Fig. 12.3). As noted earlier, marriage and household migration are based on the movement of migrants with their dependents, which is another, and under-discussed feature of internal migration and one that had major ramifications during the pandemic (Rajan & Sivakumar, 2018a, b).

3 Temporary and Seasonal Migration

Rural India is still heavily dependent on the agricultural sector as the primary source of employment. With agriculture closely linked to seasonality, the sector’s cycle also determines a main component of internal migration within the rural-urban migration stream (mostly temporary and seasonal). It has been estimated that 21 out of every 1000 persons in India is a temporary or seasonal migrant, with the state of Bihar having the highest proportion of 50 temporary migrants per 1000 of the population (Keshri & Bhagat, 2013).

When analysing the patterns of temporary and seasonal migration, one finds that those in the lowest quintiles by Monthly Per Capita Income overwhelmingly constitute the bulk of the temporary and seasonal migrants in the country, especially in the rural areas. These patterns reveal that poorer agricultural workers move to the urban areas to earn a livelihood during the agricultural off-season (Table 12.1).

The incidence of temporary and seasonal migration varies according to social groups as well, with the propensity for engaging in this type of migration higher among the more marginalised social groups (Table 12.2).

As we see, the incidence of temporary and seasonal migration is highest among people belonging to Scheduled Tribes in India – 45 migrants per 1000. Similarly, while not as high, those belonging to the category of Scheduled Castes show a high migration rate of almost 25 per 1000. People belonging to these two categories are amongst the most marginalised sections in society. However, the effect is far more pronounced in rural than in urban areas, with the rate of 49 per 1000 among the Scheduled Tribes and 30 per 1000 among the Scheduled Castes.

These migrants are essential for the basic functioning of both urban and rural industries as they engage inessential labour in a number of formal and mostly informal occupations in major sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, and construction as well as in brick-kilns and textiles (Deshingkar & Akter, 2009; Srivastava & Sutradhar, 2016).

These characteristics, therefore, make it clear that a large chunk of the migrant population was already living in vulnerable conditions and livelihoods. The pandemic and its subsequent response put this fact under a glaring spotlight.

4 The Government Response: Story of Missteps and Half-Measures

As the infection started spreading across the globe, the Government of India, as part of their initial response, put into place a one-day lockdown called the ‘Janta curfew’ on 22 March 2020. A few days later, it announced a nationwide lockdown from 24 March 2020, giving citizens only four hours’ notice to react. Overnight, transportation lines stopped, leaving passengers stranded and with nowhere to go. The subsequent days and months saw some of the most egregious scenes of desperation and misery in post-independence history. In the wake of the sudden shutting of businesses and industries, hundreds of thousands of migrants – mostly workers in precarious employment situations – and their dependents were forced to take the long road back, often in the most inhospitable conditions and on foot. This resulted in untold hardship, tragedy, and even death (Rajan & Heller, 2020).

Scenes of Distress During the Lockdown

The Central Government’s four-hour notice of the national lockdown announced by the Prime Minister in a public address sent panic among migrant workers who feared being stranded with no livelihood at the destination and without a way back home. The scenes of utter despair at New Delhi’s busy Anand Vihar Inter-State Bus Terminal, where thousands of migrants thronged for days to board a bus or train home, were broadcast around the world. Similar scenes were seen in places like Mumbai as well, as panic took hold during the continued lockdown. Many migrants felt they had no choice but to set out on whatever mode of transport they could find. Some had no option but to travel by foot, with tragic consequences – there were estimates of at least 200 migrant deaths on the road while trying to return home (Banerji, 2020). When Members of Parliament requested the data on job losses and deaths among migrants during lockdown, the government representative replied that they did not keep a record of this and had no data available. The government merely informed that they were among the over 10 million migrant workers who returned to their home states between March and June (Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, 2020) illustrating migrants’ marginalisation from policy debates.

Millions of migrants returned to the villages from the big cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Pune, Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Chennai as the lockdown was extended. The exact number of returnees – whether returning by their own vehicle, cycling, or on foot – is not available from government sources. However, those using government-arranged transport – buses and Shramik trains – were said to number 10.5 million, according to data cited on 14 September 2020 by the Lok Sabha, Parliament’s lower house. A large number of migrants returned to the two most populous and among the poorest states, namely Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The state-wise distribution of return migrants is shown in Fig. 12.4.

4.1 Central Government Response

On 24 March, the Central Government announced the first phase of the national lockdown, which subsequently underwent three more phases with increasingly relaxed restrictions on economic and human activity. However, on 7 June, when it was evident that further lockdowns would not be possible, the central government started initiating various phases of ‘un-lockdowns’, opening various sectors of the economy and ensuring limited mobility within the country.

The suddenness of the initial lockdown left migrants – who, as mentioned earlier, live and work in informal conditions in both rural and urban areas – exposed, and the enduring scenes of great distress caught the nation’s imagination. This put pressure on the Central Government to act. It was in this context that on 13 May, the government announced a raft of assistance measures under the moniker ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ or ‘Self-reliant India’, totalling Rs. 2 trillion (about US$ 300 billion), or 10% of GDP (Rajan, 2020b, c). The scheme was detailed by the Finance Minister and comprised five aid tranches; the second targeted migrant workers and small farmers. On 14 May, an addition Rs. 10 billion (US$ 134 million) was announced for distribution to the states for migrant welfare under the Prime Minister’s Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations (PM-CARES) fund. Each state would be given a minimum of 10% or 1 billion (US$ 13.4 million), with additional grants to be allocated based on the state’s population (50% weight) and the number of positive coronavirus cases it has (40% weight). Given that India has 28 states and nine union territories, it is unclear how this division takes place (Rajan & Mishra, 2020). The measures for migrant workers within the ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ are detailed in Table 12.3 below and can be divided into short-, medium-, and long-term measures.

While these programmes were announced in the face of the pandemic and needed by migrants long before its start, the effectiveness of these schemes is yet to be assessed.

To address the plight of stranded migrants, the government intervened with the Shramik special trains and buses to help them reach their hometowns (Dutta, 2020). However, this service was not free and migrants were being charged exorbitant fares at railway stations – which became a source of political bickering. The Supreme Court of India intervened with an order stating that the migrants would not pay any fare, with Indian Railways to bear 85% of the ticket cost and state government to cover the remaining 15% (NDTV, 2020). At the same time, a total of 9.1 million migrants travelled on both trains and buses. As of 15 June 2020, almost 4450 Shramik trains had transported more than 60 lakh (6 million) people to their destinations (The Hindu, 2020).

The federal nature of the Indian system, however, allows for states to intervene in issues concerning migrants and workers. India’s size and unequal economic and social development – especially with regards to differing windows of demographic dividends – has led to certain states being migrant receivers and others being migrant senders, with states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan as gaining states in terms of its working age population and Kerala and Tamil Nadu as losing states (Rajan & Mishra, 2020). A look at these states based on this distinction also yields a larger picture of Indian state responses.

4.2 State-Level Responses

According to the 2011 Census, Delhi, Gujarat, Kerala, and Maharashtra have been the major destination states for migrants in India; Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand, and Rajasthan are the sending states. Labour is a subject in the ‘concurrent list’ of the Indian constitution, which gives equal right for states to legislate on matters related to it. This federal nature of India’s response to handling the migrant crisis led to a variety of reactions on the part of different states. Migrant-receiving states had to contend with issues like providing stranded migrant workers adequate shelter and essential facilities, and sending states had to contend with issues of large masses of return migrants and provide them quarantine and other testing health facilities. Different policies were implemented in these states, but as we see below, they did not go far enough to address core issues.

4.2.1 Policy Responses in Receiving States

-

1.

Relief packages. In the early part of the migrant crisis, governments all over the world were scrambling to provide immediate material support to their citizens. This was the case in India as well – the Central Government announced several programmes for immediate relief, culminating in the major $300 billion package on 16 May 2020. However, when it came to state responses, the southern state of Kerala provided a template in addressing the issues of not only migrants, but also other vulnerable groups. It initially announced a comprehensive package of Rs. 200 billion (US$ 2.6 billion) to cover migrant workers’ basic necessities even before the national lockdown and the Central Government’s assistance scheme were announced. Kerala’s initiative was applauded by several countries around the world (Isaac & Sadanandan, 2020; Rajan, 2020c, d; Vijayan, 2020). Kerala was the only state to announce a comprehensive package of this sort.

-

2.

Shelter homes and meals for stranded migrants. Kerala also took the lead in providing shelter and food for migrants stranded in the state. In early April, it was found that over 65% of all government-run shelter homes in India, housing more than 300,000 migrants were in Kerala itself. Moreover, community-run kitchens ensured that migrants did not go hungry while stranded in the state (Rajan, 2020a). Similarly, the Maharashtra Government had allocated Rs. 450 million (US$ 6.03 million) to setup of shelter homes for stranded migrants with funds from the State Disaster Relief Fund. The government also made provision for mid-day meals for stranded migrant workers registered at construction sites in the cities of Mumbai, Navi Mumbai, Thane, Pune, and Nagpur (Tare, 2020). The Government of Gujarat designatedCovid-19 as a disaster under the State Disaster Relief Fund, with all expenditures for stranded migrant labourers to be covered by the Fund (PRS Legislative Research, 2020a, b).

-

3.

Food security at destinations. Providing food security for a number of migrant workers stranded at destinations became an immediate point of concern in most receiving states. The highest number of Covid-19 cases was registered in Mumbai, which has a large population that live in slum-like housing conditions. The government of Maharashtra identified around 1.88 million holders of PDS or ration cards as being below the poverty line and were supplied wheat, rice, and coarse grain under the National Food Security Act at the nominal rates of Rs. 3, Rs. 2, and Re. 1, respectively (Ashar, 2020). Another 20,000 cardholders were covered under the Antyodaya scheme. About 1 to 1.5 million newly below-poverty-line cardholders were supplied subsidised rations through the public distribution system. The Government of Kerala also set up community kitchens for stranded migrant workers through local self-help groups that at organised these facilities across the state.

Providing a Social Base: The Kerala Model to Revival

Kerala, with its approach to a holistic welfare of its citizens, won praise from around the world for its comprehensive response to the welfare of migrant workers. Apart from its response in the pandemic’s immediate wake, it also took steps towards a post-pandemic revival of its economy and society through a welfare framework. For the poor and vulnerable, Kerala sought to ensure social security during this difficult time. Accordingly, 5.5 million people – elderly, differently-abled and widows – in Kerala were paid Rs. 8500 (US$114) each and the government also provided a sum of Rs. 1000–5000 (US$13.42–67) to 460,000 persons registered in the various labour welfare funds. In addition, 15 kg of rice and a kit of pulses and condiments were distributed free to every household. Free and subsidised meals served through community kitchens and kudumbasree hotels set up since the lockdown were initiated. Moreover, Kerala is implementing two focused schemes in the aftermath of this pandemic. The first, Subhiksha Keralamis a comprehensive programme aimed at ensuring food security and the second, Vyavasaya Bhadratha, will distribute Department of Industry grants totalling Rs. 34 billion (US$ 455 million) to small, medium, and micro enterprises (MSMEs).

4.2.2 Policy Responses in Sending States

The sending states also provided enormous assistance to their non-resident fellows who worked as migrant workers outside the state. Provision of food, arrangement of transportation, and monetary cash support were important assistance provided during the lockdown. Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, and Rajasthan were prominent among states in providing support to the migrant workers originating from there.

In the early days of lockdown, the Uttar Pradesh government tried to ensure that states hosting migrants gave them adequate food and shelter. They also ensured that migrants who were travelling through the state were given adequate food and shelter as they made their way to their destinations (PRS Legislative Research, 2020c). Similar to Uttar Pradesh, the Government of Rajasthan (another important migrant-sending state) worked during the first phases of the lockdown to arrange for buses at inter-state borders to bring migrant workers home and also set up quarantine centres for them. The Government of Bihar allocated Rs. 1 billion (US$ 13.4 million) from the Chief Minister’s Relief Fund on 26 March 2020 to assist migrants stuck in other parts of the country (PRS Legislative Research, 2020c). Quarantine shelters were set up ad-hoc for the mass of returning migrants; however, reports of inadequate and unhygienic facilities led to major discontent among those who were forced to live there (Chakraborty and Ramashankar, 2020). The Bihar government also introduced measures for alleviating the suffering of migrant labourers who returned and were rendered jobless by the pandemic through cash transfers of a lump sum of Rs. 1000. Additionally the government operated 10 food centres in Delhi, which houses the largest number of Bihari migrants, and state-wide nodal officers were appointed to coordinate the relief measures.

Some state governments also took the initiative in providing employment support for migrant workers. The Odisha government, for instance, decided to pay Rs. 1500 to construction workers registered with the Odisha Building and Construction Workers’ Welfare Board. It also approved local bodies such as Gram Panchayats (village councils) and Urban Local Bodies to oversee the welfare of returning migrants, registering and providing them with 14-day quarantine facilities as well as a cash transfer of Rs. 2000 ($26.84) as an incentive for doing so (PRS Legislative Research, 2020c).

The Uttar Pradesh government announced free one-month rations for 16.5 million registered construction day-wage workers (Press Trust of India, 2020a), while the Odisha government has provided additional rice of 5 kg per head for 3 months and 1 kg of dal per card for 3 months free to 91,502 cardholders under the State Food Security Scheme. The Odisha State also distributed 1.016 million MT of food grains to beneficiaries under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) compared to normal monthly distributions of 194,000 MT (Press Trust of India, 2020b). In early April, the Odisha government extended food security coverage to all migrants who returned to the state regardless of whether they possessed a ration card or not.

On 16 June 2020, the Uttar Pradesh government announced it would set up the Uttar Pradesh Labour (Employment Exchange and Job) Commission to employ returning migrant workers in both the public and private sectors, with a particular focus to upgrade skills and boost local economies (Varma, 2020). The Madhya Pradesh government followed by announcing the formation of a migrant labour commission along the same lines (Sharma, 2020). How these commissions address the issues migrant workers face on the ground, however, remains to be seen. To increase awareness about Covid-19 and its attendant issues, the Rajasthan government established a helpline for stranded and moving migrant workers and a Jan Soochna (public information) portal to disseminate important information regarding the pandemic as these migrants returned to their homes in rural areas (Patil, 2020).

As seen above, the varied state responses were, in essence, on-the-spot reactions to the deteriorating situation surrounding the disrupted lives and livelihoods of migrant workers. However, there were many overlaps in state responses as the migrant crisis unfolded in the wake of the national lockdown. What was sorely missing was active coordination among states and between the states and the centre. This was especially evident in logistical issues for ferrying migrant workers back home and tracing. While some measures were more effective than others, it remains to be seen if migrant workers will stay at the forefront of these states’ policies as we move forward. However, the knee-jerk reactions of both the central and state governments were a testament to the lack of a framework for migrants in India. The pandemic provided an opportunity to address the issues by shining a harsh spotlight on it.

5 Missed Opportunities for Reform: The Structures that Impede Migrants

The pandemic-triggered migrant crisis brought clarity to a larger issue of exclusionary development in India, in both the rural and urban landscapes. Even though migrants form an integral part of both these landscapes, their welfare has often been relegated to the periphery of policy discussions. As we have shown, a number of migrants with temporary or seasonal jobs work in a variety of informal occupations across the country’s urban and rural milieus. They are the most vulnerable among the migrant workforce in the country and are precluded from the country’s already flimsy welfare mechanism (Rajan & Bhagat, 2021).

A close examination of how this has occurred brings about a clear picture of the issues plaguing India’s internal migrants.

5.1 Inadequacy of Legislation for Migrant Workers

To date, there is only one piece of legislation governing the conditions of migrant workers in India – the Interstate Migrant Workmen’s Act of 1979, which is applicable mostly to contractor-driven migration. However, migrant workers make up a large share of India’s informal workforce, whose conditions and rights are governed by several labour laws with no focus on migrants. Table 12.4 summarises some of prominent Acts and their provisions.

These laws, however, are more conspicuous for their non-implementation, leaving workers bereft of legal means to ensure their rights. The urban exclusion of internal migrants was flagged earlier in a report by UNESCO (2013). It found that migrants were denied access to rights in the city (Bhagat, 2017), often working in informal work with inadequate social and economic security and denied basic access to healthcare and education for their children.

5.1.1 Migrants and the Right to Amenities

In late 2015, the Government of India, through the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation (MHUPA), formed the Working Group on Migration to examine laws covering migrant workers. The Working Group submitted its report in early 2017 and noted the large contribution that migrants make to the Indian economy and society (Government of India, 2017a, b; Rajan & D’Sami, 2020). However, it also noted the vulnerabilities and the lack of economic and social security that they face throughout the country. The report made a number of recommendations, such as increased weightage on social protection programmes; enforcement of labour laws; registration of migrant workers; ensuring adequate food security by the portability of the public distribution system; ensuring adequate access to healthcare and education for migrant children; increasing opportunities for skill development; ending the requirement for state domicile to acquire government job; and, policies aimed at migrants’ inclusion into the formal financial system.

The Central Government has amalgamated the various labour laws into four labour codes, namely: (a) Labour Code on Wages; (b) Labour Code on Occupational Safety and Health; (c) Labour Code on Industrial Relations; and (d) Labour Code on Social Security. In 2020, the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Codes were passed by Parliament. These codes are a part of the rationalisation of labour legislation in India and subsumed 13 of the current labour laws that governed the health and safety conditions of establishments employing 10 or more workers. This included the Interstate Migrant Workmen’s Act and the Contract Labour Act also. This has led to the annulment or dilution of existing welfare measures for migrant workers in the future.

Certain state governments also sought to use the pandemic as a pretext to amend certain major labour laws, which were later repealed after much pushback (Press Trust of India, 2020c). These states had also amended the critical Industrial Disputes Act to raise the threshold for layoffs and retrenchment from 100 to 300 workers in a factory and the threshold membership for trade unions from 15% to 30%. These measures aimed to attract investment into the state and kick-start their economies – which is a flawed assumption at best.

5.1.2 The Invisibilisation of Dependents

When we think of migration in India, we normally fixate on the migration to various destinations of men for work, but this is misleading. Migration often involves the whole family, and the dynamics of familial migration is a sorely under-researched phenomenon in the Indian context.

One major fact of internal migration in India, as mentioned above, is the overwhelming dominance of women in its stream, amounting to some 70% of total migrants. While marriage has been cited as the main reason for migration in the past, things are changing, and more women are migrating for work and also working after migrating as a dependent (Parida & Madheswaran, 2019). However, given the low female labour participation rate in India, that percentage is still very small. A number of women migrants are still predominantly dependents and the pandemic caused significant hardships to them as well. What was notable, however, was their absence in public debate despite the images of entire families on the road home. Women in the labour force work mostly in the informal sector and are completely overlooked in any discussion. In the current context, four out of every ten women in the country suffered from job loss, amounting to 17 million women (Rajan et al., 2021). This is a major part of the story that was missing from the picture presented.

The picture is the same when examining issues of dependents like the elderly, but particularly of children. Migrants move to cities not only for better work opportunities for themselves, but also for better prospects for their children. The pandemic, however, forced hundreds of thousands of children to head back to the villages along with their families, uprooting them from not only their homes but also access to better health and education (Banerji, 2020). It is feared that a number of students will be forced to drop out of school because they have to return to villages, which suffer from inadequate educational facilities. This will lead to incalculable loss to their human development and the nation’s well-being.

The pandemic has raged through the country indiscriminately. The policies to contain its spread, however, have been extremely discriminatory – targeting the most vulnerable of the population and leaving their futures in darkness for the foreseeable future. The question from here is how we ensure that migrants get back on their feet and continue to contribute to the nation.

6 Concluding Remarks: Away Forward to Migration and Inclusive Policy

The implementation of the lockdown exposed the central government’s lack of cognizance of the migrant population and their issues. The food insecurity of migrant workers emerged as the most visible deprivation, along with shelter. The non-portability of PDS services across state lines also became evident (Srivastava, 2020). We must ensure food security through portability of the ration card in the PDS schemes in the future. As a follow up measure, the Central Government announced the ‘One Nation, One Ration Card’ to ensure portability of food security entitlement across India. If implemented successfully next year as proposed, it will go along way towards providing food security for poor migrants.

In addition, the housing scheme – which is likely to take at least 1 year to finish – does very little or nothing to alleviate the ongoing suffering of the migrant labourer. With the lockdown cutting all sources of income, few support schemes have focused on short-term financial relief as the package fails to recognise the immediate distress of migrant workers. In light of the fact that the Indian economy is set to see a contraction in growth in the coming year (World Bank, 2020), certain immediate steps need to be taken in order to integrate migration with development (Rajan, 2020d).

The apathy of the central and state governments is most visible in the collection of reliable and real-time data on migrants in the country. Collected datasets are either too fractured or irregular and out dated like the Census and National Sample Surveys, which do an inadequate job of covering seasonal and temporary migration in the country. When asked in Parliament about the data on the number of migrant workers who suffered job losses during the pandemic and those who died during their journey home, the government callously replied that it had no data for either. Not even a rough estimate was provided, laying bare exactly how marginalised the problems of migrants are in government policy. It is imperative to know the exact size and characteristics of the migrant population in order to come up with holistic and effective policies. This can be organized in numerous ways as suggested below.

The most basic way to ensure this is to have migrants voluntarily self-register at their destinations. These provisions exist in some laws, as mentioned earlier, but are ineffective. We need to have robust administrative data on the number of migrants in the country. This can be complemented with large scale datasets like the Census, the National Sample Survey, the Kerala Migration Survey (Rajan et al., 2020) and the Indian Human Development Survey to gain a disaggregated temporal view of migration.

A second initiative we could implement is issuing everyone who migrates to another state for work with a Migrant Smart Card, which can be swiped at bus or railway stations when they travel. This Smart Card would contain their socioeconomic details, may be linked to the Aadhaar or Ration Card as well as details about their work contract and employer’s details so that they have a means of official restitution in times of disputes with the employers. This will identify the holder as a migrant worker to be given benefits as per their requirements. The use of this card would also provide a real-time look at migration within the country.

Finally, it is high time the Central Government invested in a pan-India migration survey, similar to the Kerala Migration Survey that the Government of Kerala has used to great effect to understand migration patterns and trends from the state over the years (Rajan & Zachariah, 2019; Zachariah et al., 1999, 2000). It is no coincidence that Kerala handled the Covid-19 migrant crisis best. In fact, current estimates based on train passenger travel data show only the tip of the iceberg.

The government missed a huge opportunity to announce at least an ex-gratia payment to every migrant worker in the form of a Rs. 25,000 cash transfer in the immediate period. This would be compensation for the lost man-days of work and wages for migrant workers during the two-month lockdown. Cash transfers are the most efficient way to stimulate the economy, seen even in the case of the US, which provided a $1200 stimulus check for 3 months to taxpayers as part of a $1 trillion stabilisation programme (Sullivan, 2020) Even if we were to send a sum of Rs. 25,000 to every inter-state and inter-district migrant worker, earlier estimated at 140 million, this would amount to a total of Rs. 3.5 trillion, which is about one-sixth of the package announced. This cash support would have been more far more helpful for returning workers to cover some of the income they lost during the lockdown period and would have provided some form of security to help overcome their desperation, making them self-reliant in the true sense of the term (Rajan, 2020c, d).

This cash could have also stimulated local economies by giving a sizeable share of the population the purchasing power it currently lacks. This would go a long way in the revival of ‘animal spirits’, as John Maynard Keynes once famously said, within the depressed rural economies, as immediate cash transfers will ensure spending that would kickstart a multiplier effect once economic normality resumes. On the production side, the government should ensure that proper financing and credit lines – among other stimuli– should open up for industries to revive once again. This ensures that migrants have an incentive to return to destinations, which they currently will be wary of doing. Having migrants register for this cash support at the destinations would have also given the various governments an accurate estimate of the number of stranded migrants – something that we crucially lack at present.

Rural public works programmes like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act have proved to be the most robust social security net during the crisis. Along with increases in the allocated budget and in person-days of work, it is also important to increase the days of work to at least 180–200 days of work per year, or at least 15 days per month. This may still cover only a fraction of their earnings from their work at the destinations. Furthermore, this is still a conditional arrangement based on registration for work and not an immediate measure. However, it is a rights-based security net that needs to be extended to urban areas.

Migrant workers have traditionally been on the periphery of government policymaking as they are an invisible voter pool (Rajan et al., 2019). Many cannot vote in their hometowns due to the nature of their work. The portability of voting rights could emerge an empowerment strategy for migrant workers and ensure a sustainable progress in the post-pandemic world.

7 Postscript

India has seen a very sharp rise in COVID-19 infections in the second wave that started in early February 2021 and peaked near the first week of May 2021, with cases reported to be more than 400,000 and deaths about 4000 daily. This was exponentially more severe than the first wave. Although new COVID-19 cases started declining after first week of May 2021, it has devastated more lives and livelihoods. The genesis of the second wave is attributed to the lack of Covid-appropriate behaviour, social and political gatherings due to religious activities and elections that were held in between. There was also the complacency that the country had overcome the COVID-19 health crisis. However, the government was cautious in putting strict lockdowns and restrictions, and transport services were allowed to be operational. The second wave, in spite of being severe and devastating, did not create a migration crisis as seen during the first wave with its visible and pathetic exodus of migrants. This is not to say that there was not a flight of migrant workers, but that it was slower and less visible. Unfortunately, most of the policy measures for migrants announced during the first wave have not taken any concrete shape and remains mere announcements mainly due to the fact that the second wave brought forth shocking inadequacies in India’s medical infrastructure such as shortage of oxygen, hospital beds, medicines and vaccines. This demonstrates that policy measures are ad-hoc, partial and short-sighted instead of being long term, holistic and integrated.

Notes

- 1.

The senior author came to this figure based on an estimated trend of additions to migrants through previous censuses. There was an increase of 140 million migrants from 2001 to 2011. In the intervening years, given government-led urbanisation programmes like the Smart Cities initiatives, internal migration would have increased in the 2011–2021 period. However, the rise in migrants often sees a slight lag given that individual migrants move first and then bring their families to their destinations. Therefore, in the absence of a reliable estimate in the 2011–2021 period, if we were to add the same number of migrants as seen in 2001–2011 period, we have a migrant population of almost 600 million. One of the defining characteristics of internal migration in India is that 7 out of 10 internal migrants in India are women (Rajan & Sumeeta, 2019a, b).

References

Ashar, S. (2020). Maharashtra: Government steps in to secure ration supplies. The Indian Express, 24 March. https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/maharashtra-government-steps-in-to-secure-ration-supplies-6328718/

Banerji, A. (2020). Nearly 200 migrant workers killed on India’s roads during coronavirus lockdown. Reuters, 2 June. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-india-migrants/nearly-200-migrant-workers-killed-on-indias-roads-during-coronavirus-lockdown-idUSKBN2392LG

Bhagat, R. B. (2017). Migration, gender and right to city: The Indian context. Economic and Political Weekly, LII(32), 35–40. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/uttar-pradesh-forms-labour-commission-to-help-out-migrant-workers-11592364605571.html

Bhagat, R. B., Reshmi, R. S., Sahoo, H., & Archana, R. (2020). The Covid-19, migration and livelihood in India: Challenges and policy issues. Migration Letters, 17(5), 705–718.

Chakraborty, P., & Ramashankar. (2020). In quarantine shelters for migrants, one soap for 30 people, not enough food. The Times of India, 14 April. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/in-quarantine-shelters-for-migrants-one-soap-for-30-people-not-enough-food/articleshow/75138163.cms

Deshingkar, P., & Akter, S. (2009). Migration and human development in India (Human Development Research Paper 2009/13). United Nations Development Programme.

Dutta, A. (2020). Shramik Trains in their last leg of operation, more than 57 lakh ferried. Hindustan Times, 3 June.https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/demand-for-shramik-trains-sees-a-decline/story-ACVJ8xwXZo00Le5QzJFj1J.html

Ellis-Petersen, H., & Chaurasia, M. (2020). India racked by greatest exodus since partition due to coronavirus. The Guardian, 30 March.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/30/india-wracked-by-greatest-exodus-since-partition-due-to-coronavirus

Government of India. (2011). Census of India D-2 and D 3 tables. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India.

Government of India. (2017a). India on the move and churning: New evidence, 264–282. Economic survey 2016–17. Ministry of Finance.

Government of India. (2017b). Report of the Working Group on migration. Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation.

Gupta, S. (2020). 30% of migrants will not return to cities: Irudayarajan. Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/30-of-migrants-will-not-return-to-cities-irudaya-rajan/articleshow/76126701.cms

Isaac, T. T., & Sadanandan, R. (2020). Covid-19, public health system and local governance in Kerala. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(21), 35–40.

Keshri, K., & Bhagat, R. B. (2012). Temporary and seasonal migration: Regional patterns, characteristics and associated factors. Economic and Political Weekly, XKVII(4), 81–88.

Keshri, K., & Bhagat, R. B. (2013). Socioeconomic determinants of temporary labour migration in India: A regional analysis. Asian Population Studies, 9(2), 175–195.

Kone, Z. L., Liu, M. Y., Mattoo, A., Ozden, C., & Sharma, S. (2018). Internal borders and migration in India. Journal of Economic Geography, 18(4), 729–759.

Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. (2020). Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 2044, 22 September 2020. http://164.100.24.220/loksabhaquestions/annex/174/AU2044.pdf

NDTV. (2020). No fares for migrants, states, railways to provide food: Supreme Court. News, 28 May. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/supreme-court-on-migrants-crisis-railways-to-send-trains-when-states-ask-supreme-court-on-migrant-crisis-2236655

Parida, J. K., & Madheswaran, S. (2019). Unexplored facets of female migration. In S. I. Rajan & M. Sumeeta (Eds.), Handbook on internal migration in India. Sage.

Patil, I. (2020). Containment and welfare: Rajasthan’s two-pronged response to Covid-19. University practice connect. Azim Premji University. https://practiceconnect.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/containment-and-welfare-rajasthans-two-pronged-response-to-covid-19/

Press Trust of India. (2020a). Coronavirus outbreak: Uttar Pradesh Govt announces Rs 1000 financial aid, free ration to daily wage labourers. Release, 21 March. https://www.firstpost.com/india/coronavirus-outbreak-uttar-pradesh-govt-announces-rs-1000-financial-aid-free-ration-for-a-month-to-daily-wage-labourers-8174961.html

Press Trust of India. (2020b). Covid-19: Odisha Govt to provide Rs 3,000 to 65,000 vendors amid lockdown. India Today, 29 March. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/covid-19-odisha-govt-to-provide-rs-3-000-to-65-000-vendors-amid-lockdown-1660855-2020-03-29

Press Trust of India. (2020c). Rajasthan restores working hours to eight in factories. The Hindu, 26 May. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/rajasthan-restores-working-hours-to-eight-in-factories/article31677593.ece

Prime Minister’s Office, Government of India. (2020). PM launches Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyaan on 20June 2020 to boost employment and livelihood opportunities for migrant workers returning to villages, in the wake of COVID-19 outbreak. Release, 20 June. https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/pm-launches-garib-kalyan-rojgar-abhiyaan-on-20th-june-2020-to-boost-employment-and-livelihood-opportunities-for-migrant-workers-returning-to-villages-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-outbreak/

PRS Legislative Research. (2020a). Maharashtra Government’s response to Covid-19. https://www.prsindia.org/theprsblog/maharashtra-government%E2%80%99s-response-covid-19-till-april-20-2020

PRS Legislative Research. (2020b). Odisha Government’s response to Covid-19. https://www.prsindia.org/theprsblog/odisha-government%E2%80%99s-response-covid-19

PRS Legislative Research. (2020c). UP Government’s response to Covid-19. https://www.prsindia.org/theprsblog/government%E2%80%99s-response-covid-19-till-april-22

Rajan, S. I. (2013). Internal migration and youth in India: Main features, trends and emerging challenges (Discussion Paper). UNESCO.

Rajan, S. I. (2020a). Kerala’s experience with Covid-19: What lessons to learn? SocDem Asia Quarterly, 9(2), 18–22.

Rajan, S. I. (2020b). No package for internal migrants. In The stimulus package in five instalments does it make the economy more self-reliant? (Commentary on India’s Economy and Society Series) (Vol. 15, pp. 23–25). Centre for Development Studies.

Rajan, S. I. (2020c). Pandemic and migrants: Missed opportunities and the road ahead. In S. Baru (Ed.), Beyond Covid’s shadow: Mapping India’s economic resurgence (pp. 254–266). Rupa Publications.

Rajan, S. I. (2020d). Covid-19-led migration crisis: A critique of policies. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(48), 13–16.

Rajan, S. I., & Bhagat, R. B. (2021). Internal migration in India: A policy to integrate migrants with development (KNOMAD Policy Brief 12). World Bank.

Rajan, S. I., & D’Sami, B. (2020). The way forward on migrant issues. Frontline, 22 May.

Rajan, S. I., & Heller, A. (2020). India. Report submitted to the The Mobility, Livelihood and Wellbeing Lab (MoLab) at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Germany.

Rajan, S. I., Kumar, A., & Heller, A. (2019). The realities of voting in India: Perspective from internal labour migrants. Economic and Political Weekly, LIV(18), 12–14.

Rajan, S.I. and U. S. Mishra. 2020. Resource allocation in lieu of state’s demographic achievements in India: An evidence-based approach. Centre for Development Studies Working Paper No. 492..

Rajan, S. I., Rajagopalan, R., & Sivakumar, P. (2021). The long walk towards uncertainty: The migrant dilemma in times of Covid-19. In A. Hans et al. (Eds.), Migration, workers and fundamental freedoms: Pandemic vulnerabilities and states of exception in India. Routledge.

Rajan, S. I., & Sivakumar, P. (2018a). Introduction. In S. I. Rajan & P. Sivakumar (Eds.), Youth migration in emerging India: Trends, challenges, and opportunities (pp. 1–31). Orient BlackSwan.

Rajan, S. I., & Sivakumar, P. (Eds.). (2018b). Youth migration in emerging India: Trends, challenges, and opportunities. Orient BlackSwan.

Rajan, S. I., Sivakumar, P., & Sriinvasan, A. (2020a). The Covid-19 pandemic and internal migration in India: A ‘crisis of mobility’. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(4).

Rajan, S. I., Sivakumar, P., & Sriinvasan, A. (2020b). Impact of Covid-19 on internal migrants in India. Status Paper Submitted to the UNICEF.

Rajan, S. I., & Sumeeta, M. (2019a). Women workers on the move. In S. I. Rajan & M. Sumeeta (Eds.), Handbook on internal migration in India. Sage.

Rajan, S. I., & Sumeeta, M. (Eds.). (2019b). Handbook on internal migration in India. Sage.

Rajan, S. I., & Zachariah, K. C. (2019). Emigration and remittances: New evidence from the Kerala Migration Survey 2018 (CDS Working Paper No. 483). Centre for Development Studies.

Rajan, S. I., Zachariah, K. C., & Kumar, A. (2020). Large scale migration surveys: Replication of Kerala model of migration surveys to India migration survey 2024. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), India migration report 2020: Kerala model of migration surveys. Routledge.

Sharma, Y. S. (2020). MP forms migrant labour commission to provide employment. The Economic Times, 26 June. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/mp-forms-migrant-labour-commission-to-provide-employment/articleshow/76649692.cms

Srivastava, R. (2020). Vulnerable internal migrants in India and portability of social security and entitlements. Institute for Human Development.

Srivastava, R., & Sutradhar, R. (2016). Labour migration to the construction sector in India and its impact on rural poverty. Indian Journal of Human Development, 10(1), 27–48.

Sullivan, E. (2020). 5 takeaways from the coronavirus relief package. The New York Times, 25 March. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/us/politics/1200-dollar-stimulus-check-coronavirus.html

Tare, K. (2020). Maharashtra Govt allocates Rs. 45 crore for shelter, food for migrant workers but finds no takers for shelters. India Today, 30 March. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/maharashtra-govt-allocates-rs-45-crore-for-shelter-food-for-migrant-workers-but-finds-no-takers-for-shelters-1661533-2020-03-30

The Hindu. (2020). 60 lakh migrants took 4,450 Shramik specials to reach their home states: Railways, 15 June. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/60-lakh-migrants-took-4450-shramik-specials-to-reach-their-home-states-railways/article31834747.ece

Tumbe, C. (2018). India moving: A history of migration. Penguin Random House India Private Limited.

UNESCO. (2013). Social inclusion of internal migrants in India. UNESCO.

Varma, G. (2020). Uttar Pradesh forms labour commission to help out migrant workers. Livemint, 17 June. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/uttar-pradesh-forms-labour-commission-to-help-out-migrant-workers-11592364605571.html

Vijayan, P. (2020). Challenges in the midst of the Covid-19 epidemic. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(24), 11–13.

World Bank. (2020). Global economic prospects, June 2020: Pandemic, recession: The global economy in crisis. World Bank.

Zachariah, K.C., E. T. Mathew, and S. Irudaya Rajan. 1999. Impact of migration on Kerala economy. CDS Working Paper 297..

Zachariah, K.C., E. T. Mathew, and S. Irudaya Rajan. 2000. Socio-economic and demographic consequences of migration in Kerala. CDS Working Paper 303.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rajan, S.I., Bhagat, R.B. (2022). Internal Migration and the Covid-19 Pandemic in India. In: Triandafyllidou, A. (eds) Migration and Pandemics. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81210-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81210-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-81209-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-81210-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)