Abstract

In this chapter, I review research analyzing heterogeneity in neighborhood effects on educational attainment. Using a life-course perspective on neighborhood effects, I describe four potential models of effect heterogeneity: cumulative advantage, cumulative disadvantage, advantage leveling, and compensatory advantage. Extant research most thoroughly explores effect heterogeneity by family socioeconomic background with evidence in support of multiple models. Research on secondary outcomes like achievement and dropout finds evidence of a cumulative disadvantage model, whereas research on bachelor’s degree completion finds evidence of an advantage leveling model. Still, scholarship on heterogeneity in neighborhood effects is in its nascency, and I conclude this chapter with several recommendations for future directions in research.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

There is growing scientific consensus that the socioeconomic conditions of the neighborhood(s) in which an individual grows up play an important role in their educational outcomes. Socioeconomic (dis)advantage in children and youth’s residential neighborhoods (hereafter “neighborhood (dis)advantage”) is associated with their test scores (Burdick-Will et al., 2011), the likelihood of dropping out of high school (Wodtke, Harding, & Elwert, 2011), and chances of earning a bachelor’s degree (Levy, 2019). In recent studies, researchers suggest that these relationships are, at least in some cases, likely to be causal (Chetty, Friedman, Hendren, Jones, & Porter, 2018).

Yet, the causal nature of the relationship between neighborhood conditions and educational outcomes was, until recently, in doubt. Following strong observational and quasi-experimental evidence that neighborhoods affect life chances (Massey & Denton, 1993; Rosenbaum, 1995; Wilson, 1987), the United States (U.S.) federal government established the Moving to Opportunity Demonstration Program (MTO) in the late 1990s. MTO used a randomized controlled trial research design by assigning program participants from highly impoverished neighborhoods of five large cities to either receive housing vouchers to move out of their neighborhood and into a low-poverty neighborhood (treatment group) or not receive the vouchers but still remain eligible for other standard government services (control group). To the surprise of many, the interim and final impact evaluations of MTO found little to no effect of moving to a low-poverty neighborhood on students’ academic achievement, course selection, or educational attainment (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011). Given MTO’s gold-standard design for estimating causal effects, these results led researchers to conclude that neighborhood effects reported in prior studies may be of limited validity.

One potential reason for the underwhelming overall impacts of MTO, however, is heterogeneity in effects. For example, in their reanalysis of MTO, Chetty, Hendren, and Katz (2016) find that treatment-group children who moved to a low-poverty neighborhood before age 13 had better subsequent educational outcomes (than control children), whereas those treatment-group children moving at age 13 or later had, if anything, slightly worse outcomes. This aligns with the notion that neighborhood effects are strongest when the duration of an individual’s exposure is long (Clampet-Lundquist & Massey, 2008; Sampson, 2008; Wodtke et al., 2011). Other researchers find that neighborhood effects on children’s educational outcomes vary by several individual or family-background characteristics (e.g., Levy, Owens, & Sampson, 2019; Wodtke, Elwert, & Harding, 2016). This research begins to address recent calls for greater attention to heterogeneity in neighborhood effects (Harding, Gennetian, Winship, Sanbonmatsu, & Kling, 2011; Sharkey & Faber, 2014; Small & Feldman, 2012).

Adopting a life-course perspective (Elder Jr, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003) on neighborhood effects fosters explicit integration of such heterogeneity in theory development for the neighborhood effects literature. Proponents of the life-course perspective seek to understand individuals’ lives, including their trajectories and transitions, in the context of their social, structural, and historical situations. In terms of individuals’ neighborhoods, this requires attention to the nonrandom selection into neighborhoods that results from individuals’ life histories. As Sampson (2012) argues, selection into neighborhoods is a phenomenon of scientific interest itself, both as generative of and potentially resultant from neighborhood effects themselves. In addition, the life-course perspective emphasizes the interconnectedness of individuals’ lives, which necessitates exploration of family and individual backgrounds in analyzing neighborhood effects.

In this chapter, I consider past research on neighborhood effects and educational attainment from a life-course perspective to explicate four recently hypothesized and distinct models of neighborhood effect heterogeneity: cumulative advantage, cumulative disadvantage, advantage leveling, and compensatory advantage (Levy et al., 2019). With each model, one can predict a unique combination of individual/family backgrounds and levels of neighborhood socioeconomic (dis)advantage that is most likely to combine to substantively affect educational attainment. A nascent body of research suggests that the relevant model of neighborhood effects likely varies depending on the outcome (e.g., high-school graduation versus college graduation).

I begin by describing the life-course perspective, its relevance for research on neighborhood effects, and four potential forms of effect heterogeneity. Next, I review the literature on neighborhood socioeconomic conditions and educational attainment, focusing specifically on effect heterogeneity by family socioeconomic background, to evaluate the extent to which each model accords with current research. I conclude with a forward-looking agenda for researchers examining neighborhood effects on educational outcomes.

Neighborhood Effects and the Life Course

The life-course perspective (Elder et al., 2003) offers five general principles for studying individuals’ development and status attainment: embeddedness in time and place, linked lives, constrained agency, life-span development, and timing of events during the life course. The first three are central to the traditional literature on neighborhood effects. Embeddedness in time and place highlights the salience of individuals’ specific social locations for their development. The linked lives principle emphasizes the interdependence of individuals in a network of social relationships as their lives unfold. Constrained agency underscores how individuals construct their lives through choices made within the opportunities and constraints of their own unique circumstances. Combining the three principles, one can argue that the neighborhoods in which children and youth are embedded, including the social relationships formed in those neighborhoods, potentially constrain their opportunities, choices, and ultimate life chances.

A long-running body of research indicates that growing up in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood is negatively associated with a child’s educational outcomes (Chetty et al., 2016; Sharkey & Faber, 2014). There are several potential mechanisms for this relationship, including neighborhood social organization, relative deprivation or affluence, exposure to violence, quality of neighborhood institutions, and exposure to environmental toxins. I review these mechanisms briefly here; for in-depth discussion, see Galster (2012) and Jencks and Mayer (1990).

In terms of social organization, proponents of the collective socialization hypothesis (e.g., Wilson, 1987) posit that neighborhood adults serve as evidence of local life chances. To the extent that few adults are working in middle- or upper-class jobs, economic disaffection is likely to increase and diminish the perceived value of education. Alternatively, the density of adults with college degrees or high-status jobs is positively associated with child outcomes (Duncan, 1994), which might reflect the salience of neighborhood advantage for the perceived value of a college degree and social capital to support degree attainment. A somewhat related, though distinct, mechanism of neighborhood socialization is collective efficacy. Neighborhoods high in collective efficacy evince shared social norms and the willingness of adults to intervene to enforce those norms (Sampson, Morenoff, & Earls, 1999). Scant research investigates how neighborhood collective efficacy affects educational attainment, but it is associated with other health and behavioral outcomes (Browning, Burrington, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2008; Browning & Cagney, 2002). The norms and attitudes of students’ neighborhood peers may also play an important role in their educational decisions. For example, Harding (2011) finds that adolescents living in neighborhoods where their peers have significant heterogeneity in attitudes toward school and future schooling are less likely to matriculate to college—even if that is their stated preference. In sum, the social norms of a neighborhood may affect the educational outcomes of its residents in several ways.

Socialization processes reflect one way in which the lives of a neighborhood’s children and youth are linked with those of their fellow residents. Another example of linked lives is the level of relative deprivation or affluence an individual child possesses in comparison to their neighborhood peers. Supporters of relative socioeconomic (dis)advantage theories posit that relative deprivation leads to feelings of dissatisfaction or inferiority, whereas relative affluence can increase self-efficacy (Jencks & Mayer, 1990). The few researchers specifically investigating this phenomenon tend to focus on relative deprivation, and their findings are mixed (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2017; Turley, 2002). It is possible, however, that any detrimental effects of relative deprivation are offset by benefits of affluent peers. Family income is increasingly strongly associated with academic achievement (Reardon, 2011), and having high-achieving peers is beneficial to a student’s own levels of achievement (Hanushek, Kain, Markman, & Rivkin, 2003). Thus, neighborhood peer effects on educational outcomes may be quite complex and difficult to empirically assess.

Growing up in neighborhoods with high levels of violence negatively affects students’ cognitive abilities and test scores. For example, exploiting exogenous variation in the timing of homicides and survey interviews in Chicago, Sharkey (2010) finds that in the week following a homicide in their neighborhood, children’s cognitive performance declines by one half to two-thirds of a standard deviation. Using a similar study design in New York City, Sharkey, Schwartz, Ellen and Lacoe (2014) find that this effect generalizes to exposure to any type of violent crime on a child’s street segment. Because violence is disproportionately concentrated in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods (Sampson & Groves, 1989), it is another potential mechanism for the negative relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and residents’ educational outcomes.

Neighborhood institutions and organizations can provide residents with important resources as well as connections to other services or resources (Small, 2006). One neighborhood-based institution that likely affects educational outcomes is the school itself. Generally, school assignment in the United States is neighborhood-based. Both neighborhood and school segregation by family income are significant and growing (Owens, Reardon, & Jencks, 2016; Reardon, Bischoff, Owens, & Townsend, 2018). Because U.S.school funding is based, in part, on local property taxes—along with other federal, state, and local revenue—variation in property values can create substantial inequalities between districts. Still, reforms and legal challenges beginning in the 1970s have led to much more equitable funding across districts (Jackson, Johnson, & Persico, 2016). Currently, school districts serving low-income populations actually receive slightly more funding per student than districts serving middle- or high-income populations. Yet, the cost to educate a low-income student is significantly higher than to educate a high-income student, especially in low-income school districts. As a result, funding parity does not imply students’ needs are equally met. Moreover, low-income school districts have, on average, teachers that are less experienced, less likely to be certified, and paid less (Owens & Candipan, 2019). In sum, differences in school quality might explain the relationship between neighborhood (dis)advantage and educational attainment.

Environmental toxins represent another potential mechanism for neighborhood effects. In the United States, industrial facilities are disproportionately concentrated in nonwhite and lower income neighborhoods, yielding sizable disparities in exposure to air pollution that persist over time (Ard, 2015; Crowder & Downey, 2010; Pais, Crowder, & Downey, 2014; Taylor, 2014). These industrial air pollutants are negatively associated with student academic and health outcomes (Mohai, Kweon, Lee, & Ard, 2011). In addition to air toxins, soil and water pollutants represent other sources of environmental inequality. For example, lead exposure is highest among low-income, nonwhite populations (Sampson & Winter, 2016). Given its negative effects on academic outcomes (Muller, Sampson, & Winter, 2018), lead exposure may help explain the race and class achievement gaps. In sum, through myriad environmental, institutional, and social pathways, children and youth’s embeddedness in specific neighborhoods likely affects their educational trajectories in important ways.

The three life-course principles discussed above—embeddedness in time and place, linked lives, constrained agency—have long been the domain for research on neighborhood effects. Yet, the two other, less-applied principles offer important insights into how and for whom neighborhoods might matter. The principle of life-span development emphasizes a long-term perspective on individual development (Elder et al., 2003). For example, examining inequalities in academic achievement and educational attainment as outcomes of decades-long processes of life-span development requires analysis of prolonged neighborhood exposures. Galster (2012) alludes to this idea with the notion of durability of the dosage for neighborhood effects, and authors of a growing body of research are exploring the impact of cumulative neighborhood exposures within one generation (Levy et al., 2019; Sampson, Sharkey, & Raudenbush, 2008; Wodtke et al., 2011, 2016) or across generations (Sharkey & Elwert, 2011). The timing principle notes that the impacts of various events and experiences likely differ by their timing within the life course (Elder et al., 2003). Although recent evidence suggests that neighborhood conditions during adolescence are likely salient for high-school graduation odds (Wodtke et al., 2016), researchers nevertheless lack sufficient evidence to develop a general theory of age heterogeneity in neighborhood effects.

Research on neighborhood effect heterogeneity has only recently begun in earnest. A particular focus of recent work is heterogeneity by family socioeconomic background. This research emphasizes children and youth’s embeddedness in multiple contexts—neighborhoods and families—that have interacting effects to constrain or augment their life chances. It also applies dual conceptions of linked lives. First, children are socialized in neighborhoods with adults that have a range of economic and social capital while simultaneously cocreating peer effects with their neighborhood peers. Second, children grow up in families that have varying levels of socioeconomic resources to support their development; these resources structure both neighborhood attainment and the ways in which children experience their neighborhoods. Drawing on the principles of life-course research, I proceed to elucidate four models of neighborhood effect heterogeneity by family socioeconomic background.

Four Theoretical Models of Neighborhood Effect Heterogeneity by Family Socioeconomic Background

Cumulative Advantage

A cumulative advantage model of neighborhood effects represents one way in which neighborhood-based inequalities might develop over individuals’ life spans. Supporters of the cumulative advantage model posit widening inequality over time as past advantages beget and compound with present and future advantages (Dannefer, 2003; DiPrete & Eirich, 2006). In the context of neighborhoods, this suggests that long-term residence in an advantaged neighborhood will produce large benefits for educational outcomes, whereas only episodic residence in advantaged neighborhoods will yield little to no benefit. Given that those who reside in advantaged neighborhoods tend to remain in them (South, Huang, Spring, & Crowder, 2016), these types of long-term exposures seem likely to occur. In addition, a strict cumulative advantage model would predict little to no difference in educational outcomes between long-term residence in disadvantaged neighborhoods and long-term residence in middle-class neighborhoods—those that are neither especially advantaged nor especially disadvantaged.

Of course, neighborhood conditions represent just one of the many predictors of children’s educational outcomes. Parents’ socioeconomic status and educational attainment, for example, are other key predictors of educational attainment (Davis-Kean, 2005; Duncan & Magnuson, 2005). The principle of linked lives identifies these types of social (dis)advantages in individuals’ networks as salient features affecting their development over the life-course. Considered from a cumulative advantage perspective, growing up in a high-income, highly educated household is likely to interact with advantaged neighborhood conditions to yield especially strong benefits for educational outcomes. That is, the individuals most likely to benefit from growing up in advantaged neighborhoods are those with other social advantages.

The cumulative advantage model aligns well with past research on educational outcomes. With his classic “skill begets skill” argument (2000), Heckman theorizes that early advantages are critical for academic success. Advantages in early childhood correlate with higher levels of cognitive skills in the same period; these higher levels of cognitive skills leave children poised to leverage subsequent advantages in schooling and social environments into even greater returns to their cognitive skills. An advantaged neighborhood environment in adolescence, for example, would have an overall stronger positive relationship with academic achievement for youth who also lived in advantaged neighborhoods during early childhood than youth who lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods during early childhood because of the early achievement differences associated with early neighborhood environments.

Cumulative Disadvantage

Conceptually related to, though distinct from, the cumulative advantage model is the cumulative disadvantage model. Proponents of the cumulative disadvantage model similarly posit widening inequality over time; in this case, however, it is past disadvantages that beget and compound with present and future disadvantages (Dannefer, 2003; DiPrete & Eirich, 2006). Thus, a cumulative disadvantage model of neighborhood effects predicts that long-term residence in a disadvantaged neighborhood will negatively affect educational outcomes, whereas short-term neighborhood disadvantage will have more modest, if any, effects. In addition, other family, school-related, or social disadvantages may compound with neighborhood disadvantage to yield especially strong negative effects.

Although cumulative disadvantage may at first appear to be a corollary to cumulative advantage, a strict cumulative disadvantage model would predict little to no difference in educational outcomes between long-term residence in advantaged neighborhoods and long-term residence in middle-class neighborhoods. In other words, it is only residence in disadvantaged neighborhoods that has a significant effect on educational outcomes. This distinction between cumulative advantage and disadvantage underscores potential nonlinearity in neighborhood effects. Nonlinearity occurs when the impact of a specific change in neighborhood conditions varies across the distribution of neighborhood conditions. For example, a 10-percentage-point increase in neighborhood poverty from 30% to 40% poverty might be much more (or less) impactful for educational outcomes than an equivalent increase from 20% to 30% poverty. In their reanalysis of MTO effects by study site, Burdick-Will et al. (2011) find suggestive evidence for nonlinearity in the impact of neighborhood disadvantage on academic achievement. Other researchers similarly argue for critical threshold effects in conditions like neighborhood poverty. Crane (1991) finds that in neighborhoods where four percent or fewer of adults work in high-status jobs, teenagers’ risks for dropping out of high school or becoming pregnant increase significantly. Levy (2019) observes that for neighborhood poverty, 25% may be a key threshold above which neighborhoods negatively affect postsecondary educational attainment.

Cumulative advantage and disadvantage models can evoke the notion of path dependence—initial (dis)advantages definitively causing future (dis)advantages—but this is not necessarily the case. It is true that an individual’s level of neighborhood disadvantage at one point in time is predictive of their future neighborhood disadvantage (South et al., 2016). This reflects long-running racial and class inequalities in neighborhood segregation in the United States (Bischoff & Reardon, 2014; Massey & Denton, 1993; Sharkey, 2013). Yet, children often make residential moves during their childhood, and a sizable majority of children will reside in neighborhoods that fall within different quintiles of disadvantage while growing up (Wodtke et al., 2011). Many of these changes reflect moderate changes in neighborhood disadvantage—increases or decreases in disadvantage of one or two quintiles. Some of the changes, however, are more dramatic. Using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), Wodtke et al. (2016) find that among both black and white children born between 1966 and 1980, roughly 2.4% of each group had a change in neighborhood disadvantage level of three or four quintiles from between childhood and adolescence. These findings suggest that although substantial changes in neighborhood disadvantage across the early life course are not commonplace, they are not extraordinary either.

Advantage Leveling

The variability in neighborhood conditions across one’s life course highlights the possibility that adolescent neighborhoods may counteract childhood neighborhood effects—or the effects of other social (dis)advantages earlier in the life course (Levy, 2019). An advantage leveling model draws upon both the life-course principles of timing and life-span development to consider trajectories or sequences of exposures in modeling individual’s outcomes. There may be a sensitive period for the impact of neighborhood disadvantage, such as adolescence (e.g., Wodtke, 2013; Wodtke et al., 2016), but this is not a requirement. Neighborhood conditions across childhood and youth may matter in roughly equivalent ways. With respect to the advantage leveling model, living in a relatively disadvantaged neighborhood during adolescence would counteract the benefits associated with neighborhood advantage during childhood.

In addition to the sequencing of neighborhood environments, the advantage leveling model also has implications for the impact of neighborhood disadvantage on children from socioeconomically advantaged families. Researchers broadly conclude that children from advantaged families and environments have, on average, higher levels of academic achievement and educational attainment (Sirin, 2005; Walpole, 2003). Yet, to realize these positive future outcomes, children and youth require developmentally rich environments that promote achievement and attainment (Alexander, Entwisle, & Olson, 2014; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood may not provide such a context, thus leveling past advantages. The advantage leveling model builds upon earlier research emphasizing stage-environment fit in youth development (Eccles et al., 1993; Roeser, 2005). Proponents of stage-environment fit posit that when a social context does not meet adolescents’ developmental needs, it will negatively affect their motivation and wellbeing. Researchers applying stage-environment fit theory have focused on school and family contexts and generally found that those contexts aligning with adolescents’ developmental needs are associated with better individual and academic outcomes (Booth & Gerard, 2014; Gutman & Eccles, 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck, Chipuer, Hanisch, Creed, & McGregor, 2006).

Compensatory Advantage

Variability in disadvantage levels of neighborhoods—and other social contexts—across individuals’ life courses presents opportunities for compensatory effects as well. Whereas the advantage leveling model predicts negative effects of disadvantaged neighborhoods for previously advantaged individuals, the compensatory advantage model posits that residence in an advantaged neighborhood might ameliorate past exposure to disadvantaged neighborhoods or other social disadvantages. Observational research examining a compensatory advantage model of neighborhood effects is scant (Levy et al., 2019), but there exists some basis for the model in the school-effects literature. Among children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, the resources available from attending school can improve cognitive skills and reduce socioeconomic disparities in skills (Downey & Condron, 2016). Raudenbush and Eschmann (2015) similarly theorize that schooling can be compensatory, especially early in the life course.

This model of neighborhood effects most closely matches the intentions of the MTO intervention. MTO provided low-income families living in high-poverty neighborhoods with vouchers to move to low-poverty neighborhoods. In essence, this reflects an attempt to attenuate disadvantages associated with past residence in concentrated poverty and low levels of family income through advantages associated with subsequent residence in low poverty neighborhoods.Footnote 1

Summary of Four Models of Effect Heterogeneity

Drawing on the life-course perspective, I present four potential models of neighborhood effect heterogeneity: cumulative advantage, cumulative disadvantage, advantage leveling, and compensatory advantage. Each model describes a unique form of neighborhood effect:

-

H1 (cumulative advantage):Neighborhood advantage will positively affect educational outcomes for children and youth with long histories of living in advantaged neighborhoods and/or other types of social advantages.

-

H2 (cumulativedisadvantage): Neighborhood disadvantage will negatively affect educational outcomes for children and youth with long histories of living in disadvantaged neighborhoods and/or other types of social disadvantages.

-

H3 (advantage leveling): Neighborhood disadvantage will negatively affect educational outcomes for children and youth with past histories of living in advantaged neighborhoods and/or other types of social advantages, diminishing some of the benefits associated with these past advantages.

-

H4 (compensatory advantage):Neighborhood advantage will positively affect educational outcomes for children and youth with histories of living in disadvantaged neighborhoods and/or other types of social disadvantages, ameliorating some of the negative impacts associated with these past disadvantages.

It is important to note that each of these models describes two types of background processes that moderate or compound the impact of neighborhood (dis)advantage. The first is the sequencing of neighborhood conditions: how current neighborhood (dis)advantage augments or counteracts the impact of past neighborhood (dis)advantage. The second is heterogeneity in the effect of neighborhood (dis)advantage based on an individual’s socioeconomic background. Although researchers have found that neighborhood effects are stronger when exposures are long lasting (Wodtke et al., 2011), most researchers studying effect heterogeneity examine variation in neighborhood effects by family socioeconomic background. Hence, I will focus on the latter in the next section, noting when researchers have indicated that long-term neighborhood conditions are salient. I now turn to research on neighborhood effects to evaluate the strength of evidence for each of these models.

Current Evidence on Neighborhood Effect Heterogeneity

Extant research on neighborhood effect heterogeneity is limited, and the topic warrants greater attention (Harding et al., 2011; Sharkey & Faber, 2014; Small & Feldman, 2012). In their recent review, Sharkey and Faber (2014) note that

[w]ith some important exceptions, much of this research is descriptive and exploratory in nature, without a clear alignment between the empirical assessment of effect heterogeneity and a theoretical basis for why the residential environment is likely to be experienced differently by specific segments of the population. (p. 569)

In the preceding section, I defined four theoretical models grounded in a life-course perspective and relevant theory. Current research provides evidence in line with several of these models.

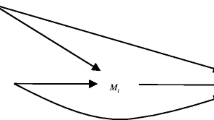

In Fig. 5.1, I summarize relevant research finding significant neighborhood effect heterogeneity that aligns with one of the four theoretical models above. The X-axis represents background family socioeconomic status (SES). Studies to the left of the origin on the X-axis find significant neighborhood effects for individuals in families with lower SES backgrounds—lower levels of household income, parental education, and the like. Studies to the right of the origin on the X-axis find significant neighborhood effects for individuals in families with higher SES backgrounds. The Y-axis represents whether neighborhood advantage or neighborhood disadvantage is more salient; studies above the origin find positive effects of neighborhood advantage, whereas studies below the origin find negative effects of neighborhood disadvantage. By placing studies in one of the four quadrants, I identify the theoretical model supported by the study’s findings. Along with the study citation, I include the educational outcome(s) affected by neighborhood (dis)advantage, as neighborhood-effect heterogeneity may vary by outcome. Note that specific location within quadrant does not connote strength of estimated neighborhood effect; rather, studies are grouped by outcome(s) affected by neighborhood (dis)advantage.

Several studies find evidence of a cumulative disadvantage model, both for test scores and odds of dropping out of high school. Capitalizing on county-levelFootnote 2 variation in job loss across North Carolina during the Great Recession that began in December 2007, Ananat, Gassman-Pines, and Gibson-Davis (2011) find that area job losses were associated with reductions in eighth-grade students’ test score achievement. Not only was the overall magnitude of these declines greater for children of parents with high-school diplomas or less, but this group also experienced immediate reductions in test scores following county job losses. Among children whose parents had more than a high-school diploma, test scores only declined after two quarters of consistent job loss—indicating buffering effects of high family SES—and were smaller in magnitude. With respect to high-school dropout risk, two studies using the PSID also find heterogeneous neighborhood effects indicative of cumulative disadvantage. Crowder and South (2003) find that for black adolescents from single-parent households and white adolescents from low-income households, the association between neighborhood disadvantage and dropout risk is particularly strong. Wodtke et al. (2016) similarly observe that neighborhood disadvantage has the strongest increase in dropout likelihood for adolescents from low-income families, although they find that this interaction applies generally to black and white adolescents. Further, they find that the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and dropping out of high school is plausibly causal for adolescents from low-income families.

Recently, researchers have also found support for the advantage leveling model. Two studies of the likelihood that an individual will complete a bachelor’s degree find that the impact of neighborhood disadvantage is strongest for adolescents with socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds. A counterfactual analysis of a nationally representative sampleFootnote 3 of adolescents enrolled in school in the late 1990s finds that those adolescents least likely to be living in concentrated poverty experience the strongest reductions in likelihood of bachelor’s attainment from living in a high-poverty neighborhood. Among the most salient family characteristics that predict avoidance of concentrated poverty are high household income, high parental educational attainment, and not receiving means-tested cash assistance or in-kind benefits—all of which indicate middle to upper family SES (Levy, 2019). Similarly, a counterfactual model of adolescents in Chicago using the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods finds that black adolescents in high-income families experience a significant, plausibly causal reduction in their likelihoods of earning a bachelor’s degree from increases in cumulative neighborhood disadvantage. The relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and bachelor’s attainment is insignificant for low- or middle-income black adolescents as well as both low- or middle-income and high-income white adolescents (Levy et al., 2019).

Why might the detrimental effects of neighborhood disadvantage vary by outcome? Specifically, why is neighborhood disadvantage most negatively associated with high-school graduation odds and, to a lesser extent, academic achievement among lowerSES students, whereas it is negatively associated with bachelor’s degree completion only among high SES students? Extant research does not provide a specific answer to this question. One possibility is that compared to completing high school, bachelor’s degree completion is difficult and often costly. Among a recent cohort of U.S. public high-school students, 85% graduated on time (The National Center for Education Statistics at IES, 2020), and even more will eventually graduate or earn an equivalent credential. Of all high-school graduates, however, less than 70% will enroll in a 2-year or 4-year postsecondary institution (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), and among first-time enrollees in 2011, only 61.8% had completed a degree within 8 years of enrollment (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2019). The myriad pitfalls along the pathway to a bachelor’s degree are well documented (Goldrick-Rab, 2016; Tinto, 2006), and they significantly reduce individuals’ odds of college graduation. Thus, a single form of disadvantage may be decisive—even for relatively advantaged adolescents. By comparison, there are greater institutional supports and fewer personal costs to high-school completion and, perhaps, academic achievement. The extent to which this explanation or some other phenomenon accounts for the variation in heterogeneous effects of neighborhood disadvantage described above merits further research.

Results from two prominent social-policy experiments yield evidence that could be interpreted as supportive of the compensatory advantage model or the cumulative disadvantage model. Both the MTO experiment and the Gatreaux Assisted Housing ProgramFootnote 4 yielded increases in college matriculation for children and youth from low-income backgrounds whose families moved to low-poverty neighborhoods when compared to those who stayed in high-poverty neighborhoods (Chetty et al., 2016; Rosenbaum, 1995). Given that the increase in college attendance is associated with a move to a lower-poverty neighborhood, one could argue for the existence of a potential compensatory effect of neighborhood advantage for past disadvantages. Yet, one could just as easily explain the results through a pattern of cumulative disadvantage; in this latter scenario, those who moved to low-poverty neighborhoods would have avoided neighborhood effects arising from prolonged exposure to a disadvantaged neighborhood.

Chetty et al. (2016) interpret their MTO results—finding significant increases in college matriculation only for youth that moved before age 13—as avoidance of a prolonged exposure throughout childhood and adolescence. Alternatively, the MTO results are equally consistent with a sensitive-period hypothesis that neighborhood effects on college matriculation operate only during adolescence. Perhaps the only way to adjudicate between these interpretations would be to compare children who moved to a low-poverty neighborhood and those remaining in a high-poverty neighborhood against a third group—those moving to a neighborhood with moderate levels of poverty. This third group, of course, does not exist in either study.

In sum, there is emerging evidence for the cumulative disadvantage and advantage leveling models of neighborhood effects. The former operates most clearly in the context of secondary achievement test scores and high-school dropout risk, whereas evidence for the latter exists for bachelor’s degree completion. There is potential, though not definitive, evidence for the compensatory advantage model, and I am aware of no evidence explicitly in support of a cumulative advantage model, although there have been few tests of this model to date.

Future Directions

Research on neighborhood-effect heterogeneity remains in its nascency, particularly for a specific outcome like academic achievement or educational attainment (Sharkey & Faber, 2014). Yet, there is growing consensus that neighborhood effects are unlikely to be uniform. In this chapter, I use a life-course perspective to describe four distinct, theory-based forms of heterogeneous effects of neighborhood (dis)advantage. Moving forward, it is important for researchers examining neighborhood effects on a variety of educational outcomes to explicitly theorize and estimate heterogeneous effects. The concern here is more than substantive; failure to model effect heterogeneity can significantly bias treatment effect estimates (Wodtke, 2018). Along with this general recommendation and description of specific models of heterogeneity, I identify four important future directions for research.

First, when informed by theory and prior research, models of neighborhood effects should go beyond estimating the impact of average cumulative neighborhood exposures across the early life course on educational outcomes. Estimating this type of neighborhood effect was an important development in recent research (e.g., Sampson et al., 2008; Sharkey & Elwert, 2011; Wodtke et al., 2011). Yet, many individuals experience substantive changes in their levels of neighborhood (dis)advantage throughout childhood and adolescence (Wodtke et al., 2011, 2016). Applying the life-course principle of timing, neighborhood conditions may be more important during certain life stages than during others. For example, Wodtke et al. (2016) find that neighborhood disadvantage during childhood is unrelated to one’s odds of dropping out of high school, but neighborhood disadvantage during adolescence significantly increases the likelihood of dropping out. Thus, models of neighborhood effects should consider potential sensitive periods. In addition, it may be possible to estimate the impact of individuals’ full trajectories of neighborhood conditions by integrating growth-curve analysis of neighborhood conditions (e.g., South et al., 2016).

Second, greater attention to and measurement of neighborhood advantage is warranted. Researchers of neighborhood effects have recently emphasized the impact of a multivariable conception of neighborhood disadvantage (e.g., Wodtke et al., 2011, 2016). Authors of an earlier body of research concluded that various forms of neighborhood advantage—neighborhoods with high occupational expectations, high-income households, and large shares of adults having college degrees or high-status jobs—are positively associated with educational outcomes (Ainsworth, 2002; Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Sealand, 1993; Duncan, 1994). Disadvantage and advantage in neighborhood conditions may be thought of as two sides of the same coin, but they appear to be distinct constructs. Neighborhood disadvantage is determined more by economic characteristics like poverty, unemployment, and public assistance receipt, whereas neighborhood advantage is determined by status characteristics like high educational attainment and high-status job holders (Levy et al., 2019). That is, neighborhood disadvantage is not simply the absence of neighborhood advantage, and neighborhood advantage is not simply the absence of neighborhood disadvantage. The salient aspect of neighborhood conditions may vary by the outcome under study. In recent years, researchers have focused more on analyzing impacts of neighborhood disadvantage rather than explicitly analyzing neighborhood advantage. Because this took place as increasing attention is given to effect heterogeneity, few researchers have explored heterogeneous effects of neighborhood advantage. This may explain the lack of evidence in the current literature for the cumulative advantage model of neighborhood effects on educational outcomes.

Third, researchers examining neighborhood effects should continue to push beyond concentrating solely on the residential neighborhood. Although I focus here on residential neighborhood effects, which is the domain of the vast majority of research on neighborhoods and educational outcomes, individuals live their lives in activity spaces that extend well beyond their residential neighborhoods (Wang, Phillips, Small, & Sampson, 2018). Hence, patterns of linked lives extend well beyond the residential neighborhood, and although one’s residential neighborhood undoubtedly influences one’s activity space, these broader exposures are distinct—and not perfectly correlated—phenomena (Browning, Cagney & Boettner 2016; Krivo et al., 2013). Researchers of neighborhood crime, for example, highlight the importance of adjacent neighborhoods (Peterson & Krivo, 2010) or non-adjacent neighborhood connections forged by residents daily rounds (Levy, Phillips, & Sampson, 2020). At the individual level, Browning, Soller, and Jackson, (2015) find that adolescents’ broader activity spaces play a significant role in explaining their engagement in various risky behaviors. These nonresidential activity space exposures may compound with—or counteract—residential neighborhood effects; that is, nonresidential exposures could function in any of the four models of effect heterogeneity highlighted here. Researchers studying neighborhood effects should continue their push to leverage various forms of data on broader activity space exposures, from mobile phone data (Palmer et al., 2013) and geolocated social media data (Phillips, Levy, Sampson, Small, & Wang, 2019; Wang et al., 2018) to travel diaries/summaries (Jones & Pebley, 2014) and census-based data (Graif, Lungeanu, & Yetter, 2017).

Finally, it will be worthwhile to consider other models of neighborhood effect heterogeneity. This chapter is necessarily limited in scope, and I have used it to elaborate models of effect heterogeneity informed by the life-course perspective. There also exists documented evidence of neighborhood-effect heterogeneity by race, gender, and age, some of which is likely associated with life-course history of disadvantage (for a review, see Sharkey & Faber, 2014). Moving forward, researchers should further develop these and other models of effect heterogeneity. In doing so, it will be especially important to iterate between ethnographic work and quantitative analyses; ethnographic research can be particularly helpful as researchers continue to build theory for neighborhood-effect heterogeneity (Small & Feldman, 2012). Although the size and scope of data currently available is unprecedented, the exploration of neighborhood-effect heterogeneity should not proceed indiscriminately. Rather, researchers should continue developing a rich set of models for how, why, and for whom neighborhoods matter (Sharkey & Faber, 2014). Integrating past insights from a diverse set of scholarship to explicate and test heterogeneous models of neighborhood effects is a necessary path forward.

Notes

- 1.

The case can also be made that MTO interrupts the cumulative disadvantage model of neighborhood effects, especially for children who were very young at the time of treatment.

- 2.

Although counties are a higher level of geography than neighborhoods, variation in job loss across North Carolina’s counties gives a plausible signal for neighborhood-level variation in job loss.

- 3.

This study analyzes students participating in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health.

- 4.

Gatreaux was a quasi-experimental housing desegregation program in Chicago that induced moves to destinations with variable neighborhood poverty rates. See Rosenbaum (1995) for additional details.

References

Ainsworth, J. W. (2002). Why does it take a village? The mediation of neighborhood effects on educational achievement. Social Forces, 81, 117–152. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2002.0038

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., & Olson, L. S. (2014). The long shadow family background, disadvantaged urban youth, and the transition to adulthood. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Ananat, E. O., Gassman-Pines, A., & Gibson-Davis, C. M. (2011). The effects of local employment losses on children’s educational achievement. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 299–314). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Ard, K. (2015). Trends in exposure to industrial air toxins for different racial and socioeconomic groups: A spatial and temporal examination of environmental inequality in the U.S. from 1995 to 2004. Social Science Research, 53, 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.06.019

Bischoff, K., & Reardon, S. F. (2014). Residential segregation by income, 1970–2009. In J. R. Logan (Ed.), Diversity and disparities: America enters a new century (pp. 208–234). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Projects/Reports.htm

Booth, M. Z., & Gerard, J. M. (2014). Adolescents’ stage-environment fit in middle and high school: The relationship between students’ perceptions of their schools and themselves. Youth & Society, 46, 735–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X12451276

Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G. J., Klebanov, P. K., & Sealand, N. (1993). Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? American Journal of Sociology, 99, 353–395. https://doi.org/10.1086/230268

Browning, C. R., Burrington, L. A., Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2008). Neighborhood structural inequality, collective efficacy, and sexual risk behavior among urban youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650804900303

Browning, C. R., & Cagney, K. A. (2002). Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated physical health in an urban setting. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 383–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090233

Browning, C. R., Cagney, K. A., & Boettner, B. (2016). Neighborhood, place, and the life course. In M. J. Shanahan, J. T. Mortimer, & M. K. Johnson (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 597–620). Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research: Vol. 2. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20880-0_26

Browning, C. R., Soller, B., & Jackson, A. L. (2015). Neighborhoods and adolescent health-risk behavior: An ecological network approach. Social Science & Medicine, 125, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.028

Burdick-Will, J., Ludwig, J., Raudenbush, S. W., Sampson, R. J., Sanbonmatsu, L., & Sharkey, P. (2011). Converging evidence for neighborhood effects on children’s test scores: An experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational comparison. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 255–276). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hendren, N., Jones, M. R., & Porter, S. R. (2018). The opportunity atlas: Mapping the childhood roots of social mobility (NBER Working Paper No. 25147). https://doi.org/10.3386/w25147

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106, 855–902. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150572

Clampet-Lundquist, S., & Massey, D. S. (2008). Neighborhood effects on economic self-sufficiency: A reconsideration of the moving to opportunity experiment. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 107–143. https://doi.org/10.1086/588740

Crane, J. (1991). The epidemic theory of ghettos and neighborhood effects on dropping out and teenage childbearing. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 1226–1259. https://doi.org/10.1086/229654

Crowder, K., & Downey, L. (2010). Interneighborhood migration, race, and environmental hazards: Modeling microlevel processes of environmental inequality. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 1110–1149. https://doi.org/10.1086/649576

Crowder, K., & South, S. J. (2003). Neighborhood distress and school dropout: The variable significance of community context. Social Science Research, 32, 659–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00035-8

Dannefer, D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 58, S327–S337. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327

Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294

DiPrete, T. A., & Eirich, G. M. (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 271–297. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123127

Downey, D. B., & Condron, D. J. (2016). Fifty years since the Coleman report: Rethinking the relationship between schools and inequality. Sociology of Education, 89, 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040716651676

Duncan, G. J. (1994). Families and neighbors as sources of disadvantage in the schooling decisions of white and black adolescents. American Journal of Education, 103, 20–53. https://doi.org/10.1086/444088

Duncan, G. J., & Magnuson, K. A. (2005). Can family socioeconomic resources account for racial and ethnic test score gaps? The Future of Children, 15, 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2005.0004

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Elder, G. H., Jr., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (Vol. 1, pp. 3–19). New York: Kluwer Academic. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1

Galster, G. C. (2012). The mechanism(s) of neighbourhood effects: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. In M. van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, & D. Maclennan (Eds.), Neighbourhood effects research: New perspectives (pp. 23–56). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2309-2_2

Goldrick-Rab, S. (2016). Paying the price: College costs, financial aid, and the betrayal of the American Dream. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Graif, C., Lungeanu, A., & Yetter, A. M. (2017). Neighborhood isolation in Chicago: Violent crime effects on structural isolation and homophily in inter-neighborhood commuting networks. Social Networks, 51, 40–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2017.01.007

Gutman, L. M., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). Stage–environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 43, 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.522

Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J. F., Markman, J. M., & Rivkin, S. G. (2003). Does peer ability affect student achievement? Journal of Applied Econometrics, 18, 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.741

Harding, D. J. (2011). Rethinking the cultural context of schooling decisions in disadvantaged neighborhoods: From deviant subculture to cultural heterogeneity. Sociology of Education, 84, 322–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711417008

Harding, D. J., Gennetian, L., Winship, C., Sanbonmatsu, L., & Kling, J. (2011). Unpacking neighborhood influences on education outcomes: Setting the stage for future research. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 277–298). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Heckman, J. J. (2000). Policies to foster human capital. Research in Economics, 54, 3–56. https://doi.org/10.1006/reec.1999.0225

Jackson, C. K., Johnson, R. C., & Persico, C. (2016). The effects of school spending on educational and economic outcomes: Evidence from school finance reforms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131, 157–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv036

Jencks, C., & Mayer, S. E. (1990). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In L. E. Lynn Jr. & M. G. H. McGeary (Eds.), Inner-city poverty in the United States (pp. 111–186). Washington, D.C.: National Academy. https://doi.org/10.17226/1539

Jones, M., & Pebley, A. R. (2014). Redefining neighborhoods using common destinations: Social characteristics of activity spaces and home census tracts compared. Demography, 51, 727–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0283-z

Krivo, L. J., Washington, H. M., Peterson, R. D., Browning, C. R., Calder, C. A., & Kwan, M.-P. (2013). Social isolation of disadvantage and advantage: The reproduction of inequality in urban space. Social Forces, 92, 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot043

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309

Levy, B. L. (2019). Heterogeneous impacts of concentrated poverty during adolescence on college outcomes. Social Forces, 98, 147–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy116

Levy, B. L., Owens, A., & Sampson, R. J. (2019). The varying effects of neighborhood disadvantage on college graduation: Moderating and mediating mechanisms. Sociology of Education, 92, 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040719850146

Levy, B. L., Phillips, N. E., & Sampson, R. J. (2020). Triple disadvantage: Neighborhood networks of everyday urban mobility and violence in U.S. cities. American Sociological Review, 85, 925–956. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420972323

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mohai, P., Kweon, B.-S., Lee, S., & Ard, K. (2011). Air pollution around schools is linked to poorer student health and academic performance. Health Affairs, 30, 852–862. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0077

Muller, C., Sampson, R. J., & Winter, A. S. (2018). Environmental inequality: The social causes and consequences of lead exposure. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041222

National Center for Education Statistics at IES. (2020). The condition of education 2020 (NCES 2020-144, U.S. Department of Education). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020144.pdf

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2019). Completing college: 2019 national report. Retrieved from https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Completions_Report_2019.pdf

Nieuwenhuis, J., van Ham, M., Yu, R., Branje, S., Meeus, W., & Hooimeijer, P. (2017). Being poorer than the rest of the neighborhood: Relative deprivation and problem behavior of youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 1891–1904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0668-6

Owens, A., & Candipan, J. (2019). Social and spatial inequalities of educational opportunity: A portrait of schools serving high- and low-income neighbourhoods in US metropolitan areas. Urban Studies, 56, 3178–3197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018815049

Owens, A., Reardon, S. F., & Jencks, C. (2016). Income segregation between schools and school districts. American Educational Research Journal, 53, 1159–1197. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216652722

Pais, J., Crowder, K., & Downey, L. (2014). Unequal trajectories: Racial and class differences in residential exposure to industrial hazard. Social Forces, 92, 1189–1215. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot099

Palmer, J. R. B., Espenshade, T. J., Bartumeus, F., Chung, C. Y., Ozgencil, N. E., & Li, K. (2013). New approaches to human mobility: Using mobile phones for demographic research. Demography, 50, 1105–1128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0175-z

Peterson, R. D., & Krivo, L. J. (2010). Divergent social worlds: Neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. Rose Series in Sociology: Vol. 12. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Phillips, N. E., Levy, B. L., Sampson, R. J., Small, M. L., & Wang, R. Q. (2019). The social integration of American cities: Network measures of connectedness based on everyday mobility across neighborhoods. Sociological Methods & Research, 50, 1110–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119852386

Raudenbush, S. W., & Eschmann, R. D. (2015). Does schooling increase or reduce social inequality? Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 443–470. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043406

Reardon, S. F. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 91–116). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Reardon, S. F., Bischoff, K., Owens, A., & Townsend, J. B. (2018). Has income segregation really increased? Bias and bias correction in sample-based segregation estimates. Demography, 55, 2129–2160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0721-4

Roeser, R. W. (2005). Stage-environment fit theory. In C. B. Fisher & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Encyclopedia of applied developmental science (Vol. 2, pp. 1055–1059). Thousand Oaks: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412950565.n403

Rosenbaum, J. E. (1995). Changing the geography of opportunity by expanding residential choice: Lessons from the Gautreaux program. Housing Policy Debate, 6, 231–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1995.9521186

Sampson, R. J. (2008). Moving to inequality: Neighborhood effects and experiments meet social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 189–231. https://doi.org/10.1086/589843

Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Groves, W. B. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 774–802. https://doi.org/10.1086/229068

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Earls, F. (1999). Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review, 64, 633–660. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657367

Sampson, R. J., Sharkey, P., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2008). Durable effects of concentrated disadvantage on verbal ability among African-American children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 845–852. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0710189104

Sampson, R. J., & Winter, A. S. (2016). The racial ecology of lead poisoning: Toxic inequality in Chicago neighborhoods, 1995–2013. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 13, 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X16000151

Sharkey, P. (2010). The acute effect of local homicides on children’s cognitive performance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 11733–11738. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000690107

Sharkey, P. (2013). Stuck in place: Urban neighborhoods and the end of progress toward racial equality. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Sharkey, P., & Elwert, F. (2011). The legacy of disadvantage: Multigenerational neighborhood effects on cognitive ability. American Journal of Sociology, 116, 1934–1981. https://doi.org/10.1086/660009

Sharkey, P., & Faber, J. W. (2014). Where, when, why, and for whom do residential contexts matter? Moving away from the dichotomous understanding of neighborhood effects. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043350

Sharkey, P., Schwartz, A. E., Ellen, I. G., & Lacoe, J. (2014). High stakes in the classroom, high stakes on the street: The effects of community violence on student’s standardized test performance. Sociological Science, 1, 199–220. https://doi.org/10.15195/v1.a14

Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75, 417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417

Small, M. L. (2006). Neighborhood institutions as resource brokers: Childcare centers, interorganizational ties, and resource access among the poor. Social Problems, 53, 274–292. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2006.53.2.274

Small, M. L., & Feldman, J. (2012). Ethnographic evidence, heterogeneity, and neighbourhood effects after moving to opportunity. In M. van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, & D. Maclennan (Eds.), Neighbourhood effects research: New perspectives (pp. 57–77). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2309-2_3

South, S. J., Huang, Y., Spring, A., & Crowder, K. (2016). Neighborhood attainment over the adult life course. American Sociological Review, 81, 1276–1304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416673029

Taylor, D. E. (2014). Toxic communities: Environmental racism, industrial pollution, and residential mobility. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Tinto, V. (2006). Research and practice of student retention: What next? Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 8, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2190/4YNU-4TMB-22DJ-AN4W

Turley, R. N. L. (2002). Is relative deprivation beneficial? The effects of richer and poorer neighbors on children’s outcomes. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10033

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). College enrollment and work activity of recent high school and college graduates summary. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/hsgec.nr0.htm

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. (2011). Moving to opportunity for fair housing demonstration program: Final impacts evaluation. Retrieved from https://www.huduser.gov/publications/pdf/MTOFHD_fullreport_v2.pdf

Walpole, M. (2003). Socioeconomic status and college: How SES affects college experiences and outcomes. The Review of Higher Education, 27, 45–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2003.0044

Wang, Q., Phillips, N. E., Small, M. L., & Sampson, R. J. (2018). Urban mobility and neighborhood isolation in America’s 50 largest cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 7735–7740. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1802537115

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Wodtke, G. T. (2018). Regression-based adjustment for time-varying confounders. Sociological Methods & Research, 49, 906–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118769087

Wodtke, G. T. (2013). Duration and timing of exposure to neighborhood poverty and the risk of adolescent parenthood. Demography, 50, 1765–1788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0219-z

Wodtke, G. T., Harding, D. J., & Elwert, F. (2011). Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective: The impact of long-term exposure to concentrated disadvantage on high school graduation. American Sociological Review, 76, 713–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411420816

Wodtke, G. T., Elwert, F., & Harding, D. J. (2016). Neighborhood effect heterogeneity by family income and developmental period. American Journal of Sociology, 121, 1168–1222. https://doi.org/10.1086/684137

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Chipuer, H. M., Hanisch, M., Creed, P. A., & McGregor, L. (2006). Relationships at school and stage-environment fit as resources for adolescent engagement and achievement. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 911–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.008

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Levy, B.L. (2022). Neighborhood Effects, the Life Course, and Educational Outcomes: Four Theoretical Models of Effect Heterogeneity. In: Freytag, T., Lauen, D.L., Robertson, S.L. (eds) Space, Place and Educational Settings. Knowledge and Space, vol 16. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78597-0_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78597-0_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-78596-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-78597-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)