Abstract

Parenting is challenging in today’s world. Dual careers, hyper-connectivity, and long distances take almost all our time, and parents must integrate their different roles. A direct impact of this hectic life is on the time parents spend with their children. Additionally, the role of fathers has gained importance, and it is important to understand his influence. In this chapter we will analyze the importance of the time fathers spend in positive engagement activities with their children, such as eating and reading with their children, and also how organizations, through their managers, can promote these positive engagement activities. Also, to show how context influences this relationship, we compare different countries in Latin America: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Positive engagement activities

- Father involvement

- Family supportive supervisor behavior (FSSB)

- Manager support

1 Introduction

Time is a scarce resource. We get it at the rate of 24 h per day. How we allocate it affects our satisfaction and the relationships we build with the people we care about. The use of time becomes most relevant when we talk about parenting. Technology has facilitated that boundaries between work and non-work hours almost disappear. Globalization has led to 24/7 demands on many employees. More women in the workforce and more single-parent families mean no backup for child and elder care at home. Rapid changes in competition, unrest in social and legal structures, and volatility in market valuation means that companies and individuals need to be agile and adaptable. For all these reasons, how we distribute time between work and family has become increasingly challenging. Also, time allocation impacts not only family life but also work life, health, satisfaction, and social behaviors.

Researchers have long studied how to facilitate both, that women enter in the work force and balance their professional career and home life. However, they have not put the same effort into studying how to foster that men enter the home sphere and balance it with their professional work. This has created an imbalance. More and more women are getting into the workplace, yet men are not entering the home sphere at the same pace. This is an unsolved issue, as men continue to feel some social pressure to be breadwinners, and since workplaces still often see balance as a women’s issue (Ladge et al. 2015) and much legislation presumes that women primarily take care of children instead of men. The study of fatherhood is likely to have a positive influence on gender equality in the workplace, and the amount of time that both parents spend with their children.

Parenting provides unique rewards, and it serves as a buffer against work problems (Kirchmeyer 1992). Family involvement helps in developing skills that are transferrable to the workplace, such as time management and patience. According to Greenhaus and Powell (2006), work-family enrichment improves life quality both in the family and work.

Fathers’ involvement at home has a positive impact on the developmental outcomes of their children (Sarkadi et al. 2007; see also earlier chapters in this volume). Lamb (2010) shows that there is not only a positive effect of fathers’ involvement, resulting in higher cognitive competencies, more empathy and more internal locus of control of their children, they also shows that the absence of the fathers results in negative outcomes, such as having lower school performance. Pleck’s research (2010) shows that interactive activities (e.g., playing and reading) between the father and his children results in children with fewer behavioral problems and better cognitive development.

In this chapter, we intend to contribute to our collective knowledge about the impact of managers on the time fathers (collaborators of those managers) spend with their children. We will focus on three significant positive engagement activities: family dinners, playing, and reading. We use data from seven Latin American countries that reveals differences between countries.

2 The Role of Fathers in Family Life

The father figure has changed through time, and it still differs across cultures. (Sarkadi et al. 2007). From an Occidental perspective, beginning in ancient Greece and Rome, the father symbolizes authority and exteriority of the family core. In ancient Greece, the polis, the public space, the politics, and war were the places where men could perform and transcend, while the home (Oikos) was the feminine place (Roy 1999). Similarly, in ancient Rome, the father (pater familias), was a symbol of power and authority over his wife and children (Amunategui 2006).

The social and economic changes in the following centuries derive from an important rural economy, where family became a productive community. Although there was a division of labor by gender, and the father was the breadwinner, his presence was constant. It was in the industrial society that the presence of the father decreased. As men started to fulfill their labor role outside the home, Lamb and Tamis-LeMonda (2004) suggest that in that change, the nature of fatherhood evolved from being the moral teacher to becoming a distant breadwinner.

The study of child and adult development has mainly focused on the impact of the mother on his or her development and socialization. The research on the father’s role started in the mid-twentieth century, mostly studying the outcomes of his presence vs. absence, as well as the impact of him co-residing with the child and the mother at home, as well as that of his economic support toward the mother (Pleck 2010).

Within the last two decades, with the increase of women in the labor force and the increase of dual-earner households, we have witnessed the rise of new expectations on the father figure. These expectations relate to his co-responsibility, his parenting impact (Pleck and Pleck 1997) and his involvement in his children’s development (McGill 2014). Yet, while the expectations on the father have grown, fathers’ role performance has changed only slowly and in low proportions (Lamb and Tamis-Lemonda 2004). In parallel, long working hours, the increase of divorces and the increase of single parent families, have all raised the concern of the absent-parent effect that may explain some contemporary social problems (Yeung et al. 2001).

Research related to the relevance of fathers in the human and social development of their children has become more critical. Research should not only focus on the outcomes of the co-residence of the father with his children, or on the effects of material support he gives to them, but research should focus on relevant issues such as the quantity and the quality of time he spends with them. To do so, researchers can use theories of parental involvement, which study a series of positive engagement activities that fathers can participate in with their children, such as spending time in family dinners, playing, and reading with them (Pleck 2007; Pleck 2010).

In the next section, we will present how the involvement of the father, in addition of that of the mother, represents an essential benefit for the child and, as a result, also to society at large. Later, we will show how positive engagement activities influence the child and adult development, and how managers can shape the time male employees who are fathers spend with their children.

3 The Importance of Fathers

Psychology literature defines family dinners, playing, and reading as positive engagement activities that the parents, and consequently the father, can have with his children. In this chapter we’ll focus on these activities, as they are relevant to understand the role of the father in human development.

The father’s involvement activities promote a secure attachment between the father and the child, which leads to positive outcomes at early ages, like self-control, and personal assurance (Cassidy and Shaver 1999; Pleck 2010). Moreover, when we consider the family social capital (Coleman 1988), parenting styles (Maccoby and Martin 1983), and proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner 1994), the father’s involvement also influences the child’s academic performance, relationships with his/her peers, and interaction with the environment.

Playing and reading provide a context where the father develops an authoritative parental style, and in turn allows the child to explore and make decisions based on his/her own reasoning. Playing and reading allow the development of proximal processes, which favor fundamental social interactions with other people and the environment. This is very relevant as interactions with other people and society help in developing the child self-confidence, conduct, and sociability. Engagement activities, such as family dinners, playing, and reading with the children, are the ideal scenarios to promote proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner 1994; Pleck 2010).

Fathers’ involvement in playing, reading, and having dinner with their children allows them to transfer family social capital, which in turn promotes cognitive development, academic achievement, and educational aspirations (Coleman 1988; Pleck 2010).

We have justified the importance of parents spending time with their children. Next, we will move to study the importance of each of the proposed activities, having family dinners, playing, and reading on the children’s development and the quality of life in adulthood. We will then move to study what influences the amount of time they spend playing with their children, and frequency they have dinner with them.

4 Positive Engagement Activities Between Fathers and Children

4.1 Family Dinners

Eating is an essential key biological function that any living being must perform. Yet, there is a key element that differentiates humans as we fulfill this activity: we are the only ones who do it as a social activity. All animals eat, but humans are the only ones that cook. So, eating together, and eating cooked food, becomes more than a necessity; it is the symbol of our humanity, what marks us off from the rest of nature. Our eating together is known as commensality. Commensality has different social functions: it strengthens the bonding of kinship; it revitalizes kinship; and it even develops significant relationships between people outside the family circle. Additionally, eating puts order to one’s social life and individual behavior at the biological level and the social level. This order does not have a universal look but happens all over the world.

Not every culture has the same rules for eating, but each culture has its own guidelines of accepted behaviors; these are known as manners. Manners are one of the first exposures of culture transference, social skills, ethics, and resource access. Lastly, one of the main functions of commensality is the socialization of individuals to follow specific rules associated with cooperation and coexistence (Fischler 2011).

Therefore, several studies catalog family dinners as one of the critical components in the development of healthy children, adolescents, and adults. This practice offers a routine that has a positive impact on the person’s quality of life and the relationship with one’s father (Buswell et al. 2012; Kalil and Rege 2015). It also allows a setting in which fathers to transfer resources to children and adolescents, such socializing them in communicative skills, manners, nutrition, and good alimentary habits,

Family dinners, in which the father is present, show to be protecting children from risky behaviors, depression symptoms, and stress (Eisenberg et al. 2004). Family dinners (or any family meal in general) are one of the primary contexts in which fathers can get involved with their children. Family meals allow the development of authoritative parental styles, proximal processes, and transference of family social capital to children (Pleck 2010). However, family dinners is a practice that is in regression in more individualistic societies (Fischler 2011) because of several demographic and organizational factors, like longer times in transportation and commuting and the increase of dual career families (Anderson and Spruill 1993).

Spending time with children during dinner increases family unity and the adaptability that families have towards changes or problems. Family dinners reduce the problems related to work-family balance because family dinners increase the probability of the father perceiving a successful personal life, despite long working hours.

There is a broad range of literature that explains the importance of family dinners with the presence of both parents for the health of children and adolescence. Evidence shows that it reduces the risk of obesity (Taveras et al. 2005) and eating disorders (Eisenberg et al. 2004). The quality of the diet increases, and healthy habits are formed (Gillman et al. 2000; Taveras et al. 2005; Videon and Manning 2003): increasing the intake of fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and reducing the probability of skipping meals such as breakfast. Besides, these effects persist to adulthood (Larson et al. 2007).

Children who eat with their fathers tend to have a considerably better relationship with them than children who do not have a father figure frequently at family dinners. This activity works as a protecting factor to drugs, alcohol and tobacco consumption, and to depressive episodes and suicidal behaviors (Eisenberg et al. 2004). An adolescent who has a bad relationship with his father is four times more likely to abuse marijuana. Adolescents that do not share dinner with their fathers have higher probabilities of abusing tobacco and alcohol than the ones who have family dinners with both parents (The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University 2012; Eisenberg et al. 2004).

Long working hours (Neumark-Sztainer et al. 2003; Mallan et al. 2014) negatively relate to the frequency of family dinners. Managers also play a crucial role in facilitating (vs. hindering) support to employees, as they are the gatekeepers of access to flexible conditions. Supervisor can display family-friendly supervisor behaviors. Supervisor family friendliness may consist of emotional support; being a role-model for effective balancing; and coming up with creative solutions to work-family challenges (Hammer et al. 2009). These types of supervisory behaviors result in higher frequency of employees’ family dinners, and lower frequency of fast food consumption (Allen et al. 2008).

4.2 Playing

Children’s development requires acquiring the conscience of oneself. Playing is one of the main social activities that allow the development of one’s own consciousness (self) and a social consciousness (me). Games provide role-playing contexts (i.e., embodying a police officer and/or a thief, playing mothers and fathers, etc.) and require understanding the rules of specific games. Playing helps to shape an identity, to understand the different roles that can be associated with being a human being, and how social expectations influence us (Mead 1934).

Psychology has linked playing more to fathers than to mothers. Even though fathers spend less time with their children than mothers do, on average they spend more time playing than mothers (Lamb and Tamis-Lemonda 2004).

Research shows that playing has an effect at an individual level for the child or adolescent, but it also has an effect at the family level. At the individual level, the frequency and quality of the game explains a higher development of cognitive and academic skills (MacWayne et al. 2013). The co-residency of the father and his child is very relevant in the case of the game because the fathers that live with their children tend to spend more time playing with them (Tamis-Lemonda et al. 2004).

Playing is also very important for a child’s conduct and relationship with his/her peers. Similar to reading, fathers who play with their children positively influence their development of self-control and reduce behavioral problems (MacWayne et al. 2013), while also improving the relationship with their peers (Kennedy et al. 2015).

Families in which fathers play with their children have better-quality life indicators and show more cohesion and family adaptability under challenging situations. Games help children to be flexible, as they are not only moments of recreation but also instances for the development of adaptability skills (Buswell et al. 2012).

Work Interfering with Family (WIF) negatively relates to the time children spend playing with their fathers (Cho and Allen 2012). Colleagues’ support is critical for parents with long working hours in allowing them to spend more time with their children (Roeters et al. 2012). However, other organizational support, like access to flexible policies, does not ensure an increase in the hours that fathers spend with their children (Kim 2018).

4.3 Reading

Shared book reading allows the child to develop his/her vocabulary since the words used in the written language are generally more complex than the oral language used by adults. Also, this activity allows the use of decontextualized language which is the language that it is used to communicate information to a person with little experience on the topic of discussion (Duursma 2014).

The quantity and the quality of the hours that a father spends reading to his children positively relates to his children’s levels of language learning (Duursma 2014). A father reading to his children shows a positive correlation to the child’s cognitive and academic skills in general. It is essential to recognize that the socio-economic level of the father acts as a moderator on this relationship (MacWayne et al. 2013)

The greater the frequency of father-child reading, the lower the child’s behavioral problems (MacWayne et al. 2013), independently of socio-economic level and maternal attachment. For this reason, behavioral parent training in vulnerable populations in the U.S. uses father-child reading in its programs (Chacko et al. 2018). Fathers who participate in these studies improved their self-reported level of discipline and their positive parenting over time. Children in this study showed higher levels of listening comprehension skills and better expressive communication (Chacko et al. 2018).

Organizations also play a role in the amount of time fathers spend with their children. Working hours are negatively related to the time fathers spend with their children. However, to the best of our knowledge, studies show that as fathers’ work hours increase, there is no change in the time they spend reading to their children (Hofferth and Goldscheider 2010).

5 The Importance of the Organizational Life on Father’s Involvement with their Children

Work and family are interconnected. The experiences in one domain (e.g., family) impact the other domain (e.g., work) (Barnett and Rivers 1996). Organizations play an essential role in promoting a positive interface between work and family and reducing the conflict between these two domains (Kossek et al. 2011).

Role accumulation theory shows that holding multiple roles (e.g., being a father and an employee) produces positive qualities for both the organization and employee, such as family commitment, strong leadership skills, and stronger welfare of employees (Ruderman et al. 2002). Holding several roles also increases productivity and satisfaction with the father’s professional career (Graves et al. 2007; Wallace and Young 2008). Researchers attribute these outcomes to work-family enrichment, or “the extent to which experiences in one role improve the quality of life in another role” (Greenhaus and Powell 2006:73). Enrichment mediates the relationship between being an involved father, and job performance (Graves et al. 2007) and the family context positively relates with work environment (Duxbury and Higgins 1991) and the benefits are bi-directional (Lapierre et al. 2018).

Organizational life affects employees work-life balance through three main dimensions: organizational policies; managerial behaviors; and values and culture. Organizational policies can promote flexibility in working hours, facilitate working from alternative places, support family care, and support personal and specific situations for sick relatives or emergencies. The implementation of policies is important in reducing the conflict between work and family.

Managerial behaviors can foster, vs. hinder, work-life balance and integration. The higher Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB), the lower the Work-to-Family Conflict (WFC), turnover intentions, and burnout. FSSB positively impacts job satisfaction and satisfaction with work-family balance among other positive employee outcomes.

The organizational culture expresses the way supervisors and peers treat people who work in the organizations, and the expectations of what the employees should be doing. Thompson et al. (1999) identified three dimensions of such culture: ‘managerial support for work-family balance, career consequences associated with utilizing work-family benefits, and organizational time expectations that may interfere with family responsibilities.’ They found that the higher the support level of work-family culture, the lower the family-to-work and work-to-family conflict.

6 The Impact of Managers on Father’s Involvement with their Children

Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) are those behaviors the supervisor displays to support the family life of their employees (Hammer et al. 2009). These behaviors include emotional and instrumental support as well as role-modeling behaviors, and instrumental support. The higher the FSSB, the lower work-family conflict and turnover intentions, and the higher work-family positive spillover, job satisfaction, and sleep quality. FSSB offers employee resources and flexibility (Rofcanin et al. 2018).

Managers’ work and home engagement influence subordinates physical and attitudinal well-being at work (Rofcanin et al. 2018). Muse and Pichler’s (2011) study of low-skilled workers finds that FSSB is negatively related to work-family conflict and positively related with job performance.

6.1 Managers and the Time Fathers Spend with their Children

There are two crucial dimensions we would like to highlight where managers affect organizational dynamics: First is time demands, and second is the impact on employees’ career.

First, organizations tend to be demanding. For such reason, how we allocate our time and resources is crucial. Supervisors set expectations in terms of whether employees should put work before family responsibilities; and how much time they should work. Second, supervisors set expectations about what is considered as good work, and who can in turn, be promotable. Thus, the supervisors set expectations about whether or not displaying commitment to family can harm one’s career.

We pose that FSSB is likely to promote the integration of work and family roles, thus leading to father’s higher frequency of family meals, playing, and reading. We measure if this impact is the same for fathers and mothers. Therefore, we use the gender of the parent as a moderator in this relationship.

In Fig. 1 we present the relationships we will test.

6.2 The Importance of the Context: The Female Percentage of the Labor Force of a Country

Although globalization impacts how we work, employee motivation, organizational work-family policies, national regulation, and social norms are still different from one country to another (Bosch et al. 2018). Thus, it is relevant that context features in the analysis of these differences (e.g., Matthews et al. 2014; Shor et al. 2013). We know form research that the context in which work-family support occurs influences its effect on individual outcomes (Las Heras et al. 2015).

We test the influence of FSSB displayed by the manager on the time fathers spend in positive engagement activities with his children, and we controlled for the context, measured by the female labor force participation of the country. We do so because culture and gender affect how men and women distribute their time. Therefore, a variable that can reflect how men and women distribute their roles is the female labour force participation. To our knowledge, it is unclear how this variable will influence the amount of time fathers spend with their children. It is an indicator of the social development of the country; therefore, we expect a positive result on the hours that both men and women spend with their children.

7 The Case of Latin America

Culture influences how people perform roles in any society. The father figure has changed over time differently in each culture. Most studies on the role of the father focus on Anglo-Saxon cultures. These countries tend to be economically developed; fathers tend to live exclusively with their nuclear family; and often times they tend to display individualistic behaviors and tendencies (Spector et al. 2004). This is rather different from the context in which most people live in Latin America. Latin American countries tend to be collectivistic (Hofstede insights 2019). In these societies family groups and ties are very strong. People expect that those of their kin will offer care, protection, and loyalty (Hofstede and Hofstede 2005). Parents usually raise their children together with the grandparents, uncles, and extended family (Hofstede and Hofstede 2005). This increases the pressure on the father figure. According to Spector et al. (2004), in these societies, family welfare is very important. Work is not and individual activity, but rather an obligation to provide for family. This might often result in fathers feeling pressure to work long hours, in which case, not seeing their children is a minor externality suffered for a greater good. In these contexts, fatherhood is recognized as one important sign of responsibility (Vigoya 2001). Latin American countries have social norms that explicitly divide the roles of men and women, with the direct consequence of fewer women in the workforce (Unterhofer and Wrohlich 2017).

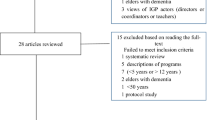

Considering the specific context of Latin American culture, we want to test the relationship between FSSB and the positive engagement activities of fathers: family dinner, playing, and reading. Thus, we took data from 22,070 individuals from 55 companies based in Latin America who participated in the IFREI 1.5 study from 2011 to 2015. This study is part of a larger research project managed by a leading European business school, whose is focused in measuring different variables of work life balance, and how this impacts individuals, families, organizations and the society. These companies operate in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic. Participants in the survey represent a wide range of Latin American countries that have different female labor force, and various levels of welfare. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Our sample includes employees working in different industries, diverse hierarchical levels and in the public as well as in the private sector. Our sample is a convenience sample using electronic and physical surveys sent out to different databases in each country and posted in the social media networks: LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter.

7.1 Measures

FSSB (Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors): We used seven items from the Hammer et al. (2009) scale to measure the subordinates’ perception of the family supportive supervisor behaviors. Items included, for example: “My supervisor is willing to listen to my problems in juggling work, and non-work life” and “My supervisor thinks about how the work in my department can be organized to benefit employees and the company jointly.” Responses were measured on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

Family Dinners, Playing and Reading: The outcome variables “Reading” and “Playing” were expressed in the number of hours, and the outcome variable “Dining” was expressed in number of days a week.

Female Labor Force Participation (FLFP): We used the percentage of labor force participation for female from the ILO.

Controls: We also control for other variables like gender, gender of the supervisor, if the couple works, age, tenure, responsibility, number of kids, and country.

7.2 Descriptive Statistics

Our final sample includes parents from the seven Latin American countries discussed. Table 1 provides details of the sample broken down by country.

Our group of interest is parents, specifically fathers, but for the first analysis, we included fathers and mothers to test if there is a difference between men and women and our variables of interest. Therefore, our sample was reduced to 16,007, since other, non-parent respondents could not answer the question of the hours they spend with their children (Table 2).

7.3 Results

7.3.1 Differences Between Countries

First, we checked if there was a significant difference between the variables across countries. Therefore, we tested our variables with a conventional ANOVA test broken down by country. The difference in the country means is significant for all our variables of interest. While Argentina reports the highest levels of family dinners, Colombia reports the lowest. In our variables of playing and reading, Guatemala reports the highest number of hours, while Colombia reports the lowest. A possible explanation for the Colombian case is that it is the country with the longest commute time to work (Statista Research Department 2018). We show results in Table 3.

7.3.2 Differences Between Fathers and Mothers

Next, we checked if there is a difference in the time fathers and mothers spend in positive engagement activities with their children. First, we compared the mean between fathers and mothers. Results are presented in Table 4.

Looking at the average, we can see that there is a difference among countries and between genders. To test which effect is stronger (gender or country), we calculated the Intraclass correlation for each variable. Results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5 shows interesting results. Except for Family Dinners, where the gender effect is higher t, in all other variables the country effect is stronger, showing that the context is very relevant to the time parents spend with their children.

7.3.3 The Manager Effects

To test if the manager and the organizational culture have an impact on the time fathers spend with their children, we ran a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Results are presented in Table 6.

Results presented in Table 4 confirm that the manager and his family-friendly behaviors impact the time fathers spend with their children. Also, results show that this influence is moderated by the gender of the parent. This means, that managers will have a greater influence with their behaviors on fathers more than on mothers. In order to see this effect, we present Figs. 1, 2 and 3 to see the moderating role of gender.

The family-friendly behaviors of the manager are positively related to the time parents spend with their children at family dinners, but this effect is stronger in fathers than in mothers. In companies where managers behave with family friendly behaviors fathers spend more time at family dinners.

Additionally, in the case of playing, FSSB has a positive impact on the time parents spend in this positive engagement activity with their children. However, gender has a moderating effect on this relationship. FSSB has a stronger positive on fathers than on mothers (Fig. 4).

Again, our results show that managers who show FSSB have a positive impact on the time parents spend playing with children. Again, gender has a moderating effect on this relationship. In the case of fathers, the positive effect becomes stronger.

8 Discussion

There is a considerable amount of research that supports the importance of parents participating in positive engagement activities with their children. Moreover, the role of fathers has gained importance. Our study recognizes the importance of fathers in the development of their children, and how organizations, through their managers, promote positive engagement activities. The time fathers spend in family dinners, playing, and reading, will also have an impact on organizations, and the development of employees’ children. This influences the talent that the organization will look for in the future. Also, as we explained before, these activities reduce several social problems that affect society and, thus, will help organizations in society.

Many factors influence the decision about parental time distribution, but as fathers spend a substantial amount of time at our jobs, managers play a key role in this decision-making process. They act as both a gatekeeper and a role model and influence the father’s decisions. Therefore, it is imperative to recognize this influence and potential outcomes, as organizations can take actions by facilitating and promoting family-friendly behaviors among their managers.

Our study also contributes to the contextual conditions to explain under which context the relationship between FSSBs and the time a father spends in family dinners, playing, and reading takes to unfold. As previous research shows, context matters (Bosch et al. 2018). Our results show that interaction between FSSB and the hours that fathers spend with their children is stronger in fathers than in mothers in Latin American countries. A potential explanation for this influence is that when managers show FSSB, fathers feel that they are also allowed to spend more time in family activities. For example, playing with your children is not confined to only women, and therefore fathers (and mothers) need to achieve work-life balance.

Our life is divided into different roles. How we distribute our time among these roles, impacts not only our welfare but also affects the people we care about. This is especially important in the parent-child relationship, where parents have a direct impact on a child’s development. An organization influences these developments. Therefore, it is relevant to continue fostering such positive dynamics to not only impact the family dimension, but also the work dimension and even society.

References

Allen TD, Shockley KM, Poteat LF (2008) Workplace factors associated with family dinner behaviors. J Vocat Behav 73(2):336–342

Amunategui CFA (2006) El Origen de los Poderes del PaterFamilias: El PaterFamilias y la PatriaPotestas. Revista de Estudios Histórico-Jurídicos, XXVIII, pp 37–143

Anderson EA, Spruill JW (1993) The dual-career commuter family: a lifestyle on the move. Marriage Fam Rev 19(1–2):131–147

Barnett RC, Rivers C (1996) She works/he works: how two-income families are happier, healthier, and better-off. Harper, San Francisco

Bosch MJ, Heras ML, Russo M, Rofcanin Y, Grau MG (2018) How context matters: the relationship between family supportive supervisor Behaviours and motivation to work moderated by gender inequality. J Bus Res 82:46–55

Bronfenbrenner U (1994) Ecological models of human development. In: Husen T, Postelthwaite TN (eds) International Encyclopedia or Education. Pergamon Press, Oxford, pp 1642–1647

Buswell L, Zabriskie R, Lundberg N, Hawkins A (2012) The relationship between father involvement in family leisure and family functioning: the importance of daily family leisure. Leis Sci 34(2):172–190

Cassidy J, Shaver PR (eds) (1999) Handbook of attachment. Theory, research, and clinical applications. The Guilford Press, New York

Chacko A, Fabiano GA, Doctoroff GL, Fortson B (2018) Engaging fathers in effective parenting for preschool children using shared book Reading: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47(1):79–93

Cho E, Allen TD (2012) Relationship between work interference with family and parent-child interactive behavior: can guilt help? J Vocat Behav 80(2):276–287

Coleman JS (1988) Social Capital in the Creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94:S95–S120

Duursma E (2014) The effects of Fathers’ and Mothers’ Reading to their children on language outcomes of children participating on early head starts in the United States. Fathering 12(3):282–302

Duxbury LE, Higgins CA (1991) Gender differences in work-family conflict. J Appl Psychol 76(1):60–74

Eisenberg ME, Olson RE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Bearinger LH (2004) Correlations between family meals and psychosocial Well-being among adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine 158(8):792–796

Fischler C (2011) Commensality, society and culture. Soc Sci Inf 50(3–4):528–548

Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Lindsay Frazier A, Rockett HRH, Camargo CA Jr, Field AE, Berkey CS, Colditz GA (2000) Family dinner and diet quality among older children and adolescents. Arch Fam Med 9:235–240

Graves LM, Ohlott PJ, Ruderman MN (2007) Commitment to family roles: effects on managers attitudes and performance. J Appl Psychol 92(1):44–56

Greenhaus JH, Powell GN (2006) When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad Manag Rev 31(1):72–92

Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Yragui NL, Bodner TE, Hanson GC (2009) Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). J Manag 35(4):837–856

Heras L, Mireia ST, Escribano PI (2015) How national context moderates the impact of family-supportive supervisory behavior on job performance and turnover intentions. Management Research 13(1):55–82

Hofferth SL, Goldscheider F (2010) Does change in Young Men’s employment influence fathering? Fam Relat 59(4):479–493

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ (2005) Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. McGraw Hill, New York

Hofstede Insights (2019) Hofstede Insight. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/chile/

Kalil A, Rege M (2015) We are family: fathers time with children and the risk of parental relationship dissolution. Soc Forces 94(2):833–862

Kennedy LB, Dunn T, Sonuga-Barke E, Underwood J (2015) Applying Pleck’s model of paternal involvement to the study of preschool attachment quality: a proof of concept study. Early Child Development Care 185(4):601–613

Kim J (2018) Workplace flexibility and parent - child interactions among working parents in the U.S. Soc Indic Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2032-y

Kirchmeyer C (1992) Perceptions of nonwork-to-work spillover: challenging the common view of conflict-ridden domain relationships. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 13(2):231–249

Kossek EE, Pichler S, Bodner T, Hammer LB (2011) Workplace social support and work–family conflict: a meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers Psychol 64(2):289–313

Ladge JJ, Humberd BK, Watkins MB, Harrington B (2015) Updating the organization MAN: an examination of involved fathering in the workplace. Acad Manag Perspect 29(1):152–171

Lamb ME (2010) How do fathers influence children’s development? Let me count the ways. In: Lamb ME (ed) The role of the father in child development, 5th edn. Wiley, London, pp 1–26

Lamb ME, Tamis-LeMonda CS (2004) Fathers’ role in child development. In: Lamb ME (ed) The role of the father in child development. Wiley, New York

Lapierre LM, Li Y, Kwan HK, Greenhaus JH, DiRenzo MS, Shao P (2018) A meta-analysis of the antecedents of work–family enrichment. J Organ Behav 39(4):385–401

Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M (2007) Family meals during adolescence are associated with higher diet quality and healthful meal patterns during Young adulthood. J Am Diet Assoc 107(9):1502–1510

Maccoby E, Martin J (1983) Socialization in the context of the family: parent- child interaction. In: Hetherington EM (ed) Handbook of child psychology: socialization, personality, and social development, 4th edn. Wiley, New York, pp 1–101

MacWayne C, Downer JT, Campos R, Harris RD (2013) Father involvement during early childhood and its association with Children’s early learning: a meta-analysis. Early Educ Dev 24(6):898–922

Mallan KM, Daniels LA, Nothard M, Nicholson JM, Wilson A, Cameron CM, Scuffham PA, Thorpe K (2014) Dads at the dinner table. A cross-sectional study of Australian fathers’ child feeding perceptions and practices. Appetite 73(1):40–44

Matthews RA, Mills MJ, Trout RC, English L (2014) Family-supportive supervisor behaviors, work engagement, and subjective Well-being: a contextually dependent mediated process. J Occup Health Psychol 19(2):168–181

McGill B (2014) Navigating new norms of involved fatherhood: employment, fathering, attitudes, and father involvement. J Fam Issues 35(8):1089–1106

Mead GH (1934) Mind, self and society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Muse LA, Pichler S (2011) A comparison of types of support for lower-skill workers: evidence for the importance of family supportive supervisors. J Vocat Behav 79(3):653–666

Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M, Croll J, Perry C (2003) Family meal patterns: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 103(3):317–322

Pleck JH (2007) Why could father involvement benefit children? Theoretical perspectives. Applied Development Science 11(4):196–202

Pleck JH (2010) Parental involvement: revised conceptualization and theoretical linkages with child outcomes. In: Lamb ME (ed) The role of the father in child development. Wiley, London, pp 67–107

Pleck EH, Pleck JH (1997) Fatherhood ideals in the United States: historical dimensions. In: Lamb ME (ed) The role of the father in child development. Wiley, London, pp 33–48

Roeters A, Van der Hippe T, Kluwer E, Raub W (2012) Parental work characteristics and time with children: the moderating effects of parent, gender and children age. Int Sociol 27(6):1–18

Rofcanin Y, Heras ML, Bosch MJ, Wood G, Farooq Mughal F (2018) A closer look at the positive crossover between supervisors and subordinates: the role of home and work engagement. Hum Relat 72(11):1776–1804

Roy J (1999) Polis and Oikos in classical Athens. Cambridge Core: Greece and Rome 46(1):1–18

Ruderman MN, Ohlott PJ, Panzer K, King SN (2002) Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Acad Manag J 45(2):369–386

Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, Bremberg S (2007) Fathers involvement and Children’s developmental outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr 97(2):153–158

Shor JJ, Greenhaus JH, Graham KA (2013) Context matters: a model of family-supportive Supervision & Work-Family Conflict. Acad Manag Proc 1:14613

Spector PE, Cooper CL, Poelmans S, Allen TD, O’Driscoll M, Sanchez JI, Siu OL, Dewe P, Hart P, Luo L (2004) A cross-National Comparative Study of work-family stressors, working hours and Well-being: China and Latin America versus the Anglo world. Pers Psychol 57(1):119–142

Statista Research Department (2018) Statista global consumer survey: mobility: duration of daily commute. https://www.statista.com

Tamis-Lemonda CS, Shannon JD, Cabrera NJ, Lamb ME (2004) Fathers and mothers at play with their 2- and 3- year olds: contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Dev 75(6):1806–1820

Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Berkey CS, Rockett HRH, Field AE, Lindsay Frazier A, Colditz GA, Gillman MW (2005) Family dinner and adolescent overweight. Obes Res 13(5):900–906

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (2012) The importance of family dinners VIII. Columbia University, New York. https://www.centeronaddiction.org/addiction-research/reports/importance-of-family-dinners-2011

Thompson CA, Beauvais LL, Lyness KS (1999) When work–family benefits are not enough: the influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work–family conflict. J Vocat Behav 54(3):392–415

Unterhofer U, Wrohlich K (2017) Fathers, parental leave and gender norms DIW (Deutsches Institut Für Wirtschaftsforschung) discussion paper 1657. German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin), Berlin

Videon TM, Manning CK (2003) Influences on adolescent eating patterns: the importance of family meals. Journal of Adolescence Health 32(5):365–373

Vigoya MV (2001) Contemporary Latin American perspectives on masculinity. Men Masculinities 3(3):237–260

Wallace JE, Young MC (2008) Parenthood and productivity: a study of demands, resources and family-friendly firms. J Vocat Behav 72(1):110–122

Yeung WJ, Sandberg JF, Davis-Kean PE, Hofferth SL (2001) Children’s time with fathers in intact families. J Marriage Fam 63(1):136–154

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bosch, M.J., Las Heras, M. (2022). Small Changes that Make a Great Difference: Reading, Playing and Eating with your Children and the Facilitating Role of Managers in Latin America. In: Grau Grau, M., las Heras Maestro, M., Riley Bowles, H. (eds) Engaged Fatherhood for Men, Families and Gender Equality. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75645-1_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75645-1_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-75644-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-75645-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)