Abstract

In the last decades, the Paris metro area has experienced important structural changes linked to rising income inequality and a rapidly growing immigrant population. Using census data from 1990, 1999 to 2015, this chapter explores these transformations and how they have shaped trends in residential segregation. We find that the occupational structure of the area shifted upwards in the recent decade with a substantial increase in the share of the top occupational groups. This trend, however, did not primarily concern the immigrant population, which nonetheless experienced a growth in the middle class. These trends were further accompanied by an increase in income inequality driven by rising wages among the top 1% earners. Despite these changes, dissimilarity indexes between socioeconomic groups and between natives and immigrants have remained quite stable over the period. However, interaction indexes suggest that neighbourhoods are becoming more homogenous over time, both in terms of socioeconomic and ethnic diversity. Finally, the findings shed light on the correlation between socioeconomic and immigrant segregation. Socioeconomic disadvantage and the presence of immigrants within neighbourhoods, especially of non-European origin, are tightly correlated, and that correlation became stronger over time.

The authors accessed the data via the Centre d’accès sécurisé distant, (CASD), dedicated to the use of authorized researchers, following the approval of the Comité français du secret statistique. This research was supported by a French state grant (grant no. ANR-10-EQPX-17) (Centre d’accès sécurisé aux données, CASD) and the ‘Flash Asile’ program of the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-16-FASI-0001 and ANR-11-IDEX-0003-02). We would also like to thank The Paris Region Development and Urban Planning Agency (IAU Ile-de-France) for providing shapefiles.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In the last decade, the population of the Paris metro area grew rapidly, and with more than 12 million inhabitants in 2015, it is one of the largest urban centres in Europe. As a major economic and political capital, the composition of its population is more polarised than the French or European average, with a smaller proportion of the middle classes and strong income inequality (Labrador 2013). Moreover, like other major cities in Western Europe, the Paris area has seen a rise in immigration in recent decades, particularly from non-European countries.

Despite these broad structural changes, relatively little evidence is available on how these transformations affected residential segregation in the Paris metro area. Since the 1980s, substantial urban renewal and social mix policies have been implemented in France with the aim of combating segregation. Policymaking has primarily targeted the poor peripheral urban areas known as the banlieues, where many immigrants from France’s former colonies settled in public housing projects. Hit by deindustrialisation and economic hardship, these areas have become synonymous with high unemployment, poor-quality schools, crime and are even symbolic of the failure of immigrant integration. Recent assessments of French urban policy document that urban renewal and social mix initiatives have been largely unsuccessful and have even had the unintended consequence of reinforcing segregation (Epstein 2011; Fol 2013). Meanwhile, an increasing number of studies suggest negative effects of living in disadvantaged and segregated neighbourhoods on employment (Gobillon et al. 2011; Petit et al. 2016).

This chapter uses French census data from 1990, 1999 and 2015 to investigate changes in occupational structure, inequality and residential segregation in the Paris metro area. We add to prior literature on segregation in Paris by using the most recent available data on the entire metropolitan area, comparing three census dates using small spatial scales comparable to census tracts (IRIS),Footnote 1 and by articulating socioeconomic and immigrant segregation. The chapter has three broad objectives: (1) to document structural changes in the urban population linked to occupation, income inequality and immigration; (2) to analyse the residential distribution of socioeconomic groups and (3) to describe trends in socioeconomic and immigrant segregation over time and the ways in which they are correlated.

2 Background

Since the 1980s, residential segregation has been a predominant target of policymaking and has received pervasive media attention in France (Lelévrier and Melic 2018). Yet, it is only recently that systematic empirical research based on representative data has shed light on spatial inequalities. Unlike the U.S. or other European contexts, which have long been concerned with the unequal spatial distribution of minorities, in France, the earliest studies tackled segregation from the angle of social class using occupational groups (Tabard 1993; Maurin 2004; Préceteille 2006). Préteceille (2006) offers one of the first studies of socioeconomic segregation in the Paris region, measuring changes in dissimilarity indexes between occupational groups in neighbourhoods between 1990 and 1999. He finds that the strongest indices are observed for upper-status occupations and are increasing over time, whereas intermediary groups are becoming less segregated. He further points out that residents of Paris still predominately live in middle-class and mixed neighbourhoods. More recent studies have weighed in on this debate using tax and administrative employee data, allowing analysis by income groups rather than occupational categories. Godechot (2013) focuses on the spatial concentration of the wealthiest households (top 1% and 0.1% of earners) and documents that the level of segregation for top earners is the strongest in Paris compared to other French cities and is on the rise. Most recently, using tax data at the communal level, Ribardière (2019) also points to an increase in residential segregation by income in the Paris area between 1999 and 2015.

Overall, despite methodological differences between these studies, the evidence indicates increasing socioeconomic segregation, owing to the strong spatial isolation of upper-status groups in particular. Below we discuss three potential mechanisms underpinning socioeconomic segregation in the Paris area: the segregation of immigrants, urban policy and public housing, and rising income inequality.

2.1 The Role of Immigrant Residential Segregation

While residential segregation in France is primarily viewed as an issue of class, that is, relating to the unequal distribution of socioeconomic groups, urban disadvantage and immigration have been historically tightly intertwined in the French context.Footnote 2 During the 1980s, post-colonial immigrants found accommodation primarily in the large public housing projects embedded in the suburbs of large urban areas (banlieues) near industrial sites where jobs were available. In the wake of deindustrialisation and rising unemployment, the banlieues became explicitly synonymous with socioeconomic disadvantage and implicitly associated with racial minorities. These neighbourhoods drew public attention following the highly mediatised urban riots during the 1980s and early 2000s involving minorities and contributed to the construction of segregation as a social problem.

It is not until the mid-2000s that research began to quantify the extent of residential segregation between immigrants and French natives (Préteceille 2009; Safi 2009; Verdugo 2011; Pan Ké Shon and Verdugo 2015). These studies analyse segregation at the municipality level from consecutive censuses. Their results show high segregation in Paris between natives and immigrants from North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and Turkey, which increased moderately between 1968 and 1999. Verdugo (2011) was the first to study the long-term evolution of immigrant segregation at the level of the census tract. He documented higher levels of segregation for non-European immigrants, which were rising largely due to the increased concentration of immigrants living in public housing. Although less is known about segregation beyond the first generation, due to restrictions in census data, a few studies indicate that spatial inequalities are largely transmitted to the second generation, particularly among non-Europeans (McAvay 2018a, b; McAvay and Safi 2018). Immigrant segregation appears to be in part maintained by discrimination on the Parisian housing market (Bonnet et al. 2016; Bunel et al. 2017) as well as native flight dynamics out of immigrant areas (Rathelot and Safi 2014; McAvay 2018a, b), particularly in areas near large public housing projects (Verdugo and Toma 2018).

These findings from France align with lessons from the U.S. about racial residential segregation. Massey and Denton (1993) emphasise how discrimination and race-based residential preferences create a segmented housing market that channel minorities into poor areas. They further make the argument that racial segregation and racial inequalities may more broadly operate as a mechanism of socioeconomic segregation and the concentration of poverty. If racial minorities have lower income on average, the spatial separation of racial groups would automatically result in segregation along class lines, separating high-income racial groups from low-income racial groups (Massey and Denton 1993; Reardon and Bischoff 2011). Quillian and Lagrange (2016) show that racial segregation and income segregation are correlated to a similar degree in France and the U.S., while McAvay and Safi (2018) show an overlap between ethnoracial and socioeconomic segregation at the individual level. Hence, it is possible that the rise in non-European immigrants and their spatial separation from natives may contribute to socioeconomic segregation in the French context.

2.2 The Role of Urban Policy and Public Housing

French urban policy emerges formally in the 1980s with the aim of reducing social inequalities, targeting specifically the so-called quartiers sensibles with large shares of public housing. The main locus of state intervention in urban areas is the public housing sector, which provides low-rent government-owned or -subsidised units (habitation à loyer modéré, or HLM). Built in the post-war period to improve living conditions and resettle slum residents, public housing projects are now associated with socioeconomic disadvantage and the concentration of minorities in the banlieues (Lelévrier 2010). With the creation of ‘priority zones,Footnote 3’ France implemented its first spatial affirmative action (Epstein 2011; Fol 2013). The most ambitious national-level urban policy plan was introduced in 2003, the Loi Borloo, with the aim of creating a social mix in priority zones through urban renewal and redistributive policies. The policies aimed to achieve a social mix by first demolishing public housing to create new real estate opportunities on the private market in these areas, with the aim of attracting the middle class; and second, by building new public housing units in areas where it is under-represented, in order to relocate poor households to more mixed spaces. While these policies are explicitly about class, many argue that they are implicitly concerned with the concentration of minorities (Epstein 2011).

More than a decade later, the social mix sought by the 2003 reform is largely considered a failure. Research even suggests that urban renewal and social mix policies had unintended consequences that contributed to reinforcing segregation. Studying these effects in the Paris area, Lelévrier (2010) shows that these policies triggered upper-class mobility out of the targeted areas, while poor households were relocated in disadvantaged areas, primarily in other sensitive urban zones. Thus, in contradiction with their stated aim, these policies actually resulted in a reconcentration of poverty by channelling similar SES households to similar areas. Further, despite the substantial resources invested in the targeted areas, Epstein (2011) emphasises the failure of spatial affirmative action as unemployment is still two times higher in sensitive urban zones compared to the national average.

Other unintended consequences of urban policy have unfolded in the public housing sector, revealing its ambiguous role in maintaining segregation. The urban policy has used public housing as a tool for maintaining social mix. The 2000 Urban Solidarity and Renewal law (SRU) made it mandatory for all cities to have at least 20% social housing. This would allow poor populations to live in more affluent municipalities and prevent them from being forced out of gentrifying areas with rising housing prices (Ribardière 2019). Yet evidence shows that the sector is strongly segregated along class lines. As income eligibility requirements are broad enough to include middle-class households, the public housing sector is not reserved for the poor (Whitehead and Scanlon 2007). However, the poorest residents tend to live in low-quality housing in poor areas, while high and middle-income households have access to higher-quality buildings in more attractive, central locations (Whitehead and Scanlon 2007; Lelévrier and Melic 2018). Public housing has also had ambiguous effects on the segregation of immigrants. A number of French urban studies have shown that social mix policies used in attributing public housing have resulted in informal racial profiling, by which the housing demand of non-European origin immigrants is channelled towards lower quality units in deprived areas (Kirszbaum and Simon 2001; Sala Pala 2013; Bourgeois 2013). Cases of institutional discrimination have been brought in front of the French courts against public housing authorities in the name of social mix policies.

2.3 The Role of Rising Income Inequality

Like other Western societies, France has experienced rising income inequality since the end of the twentieth century. Research has sought to assess how growth in inequality impacts residential segregation. Evidence from the U.S. shows that rising income inequality spurred socioeconomic segregation between 1970 and 2000 (Watson 2009; Reardon and Bischoff 2011). Reardon and Bischoff (2011) specifically demonstrate that one of the main mechanisms underlying this link is the exacerbated concentration of affluent households, whereas the concentration of poverty is unaffected by rising inequality. A similar hypothesis has been tested in France regarding the role of financialisation of the economy in spatial inequalities. Using a wide-scale administrative dataset, Godechot (2013) shows that the increase of finance jobs and high wages in the sector has intensified the segregation of top incomes in Paris. Godechot (2013) attributes this rise in spatial segregation among the wealthiest to the development of financial districts in the Western areas of Paris as well as residential avoidance strategies among the upper classes.

3 Data and Methods

We use individual-level census data from 1990, 1999 and 2015 to document changes in occupational structure, immigration and residential segregation over the period. As the census does not collect household income, we also draw on administrative employee files linked to the Permanent Demographic SampleFootnote 4 (EDP-DADS) to measure trends in income inequality in Paris and in France.

The Paris Metro Area, displayed in Fig. 17.1, is defined according to the boundaries of the Ile-de-France region.Footnote 5Ile-de-France is the most populous of all French regions, with a population of over 12 million residents. The region encompasses 1,276 municipalities and 8 departments: the city of Paris (about 2 million people), Essonne, Hauts-de-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis, Seine-et-Marne, Val-de-Marne, Val-d’Oise, and Yvelines. The area is divided between the city of Paris at its core and the surrounding suburbs: the inner outskirts called the petite couronne and the outer suburbs known as the grande couronne. These zones have approximately the same number of inhabitants, but they differ widely in terms of housing prices, which are much higher in the municipality of Paris, and the type of housing, as only the grande couronne is composed of a significant share of single household units. While the share of social housing varies widely within each zone, it also tends to be lower in the outskirts. On the other hand, the Seine-Saint-Denis department in the northeast bordering the city of Paris is well-known for concentrating high shares of immigrants, public housing projects and the poorest population of the Paris metro area.

The neighbourhood scale used is IRIS (“aggregated units for statistical information”). IRIS are infra-municipality units of about 2,500 inhabitants for all municipalities of more than 10,000 inhabitants. IRIS was not implemented until 1999, prior to which a smaller division, the îlot was used. For the sake of comparability, INSEE provides a correspondence table to match the 1990 îlots with the 1999 IRIS code so that IRIS can be used at all dates.

We measure occupation using the French socioprofessional classification (catégorie socio-professionelle) of individuals reported in the census. We recode these categories into three socioeconomic status groups: top, middle, and bottom. The top group includes managers and professionals. The middle group includes associate professionals, clerks, service workers, and craft workers. The bottom group includes machine operators and other skilled workers and unskilled workers.Footnote 6

Immigrants are categorised using the double criteria of birth nationality and country of birth and are defined as persons born abroad without French citizenship at birth. We use the country of birth of immigrants to create a broad ‘non-European immigrant’ category. French natives are persons who are born French citizens, regardless of country of birth. Because they are French-born citizens, descendants of immigrants cannot be identified in the census and are thus counted as French natives.

We use maps to visualise changes in the distribution of various socioeconomic groups in the Paris metro region. In addition, we use dissimilarity and interaction indexes to measure socioeconomic and immigrant segregation (Reardon and O’Sullivan 2004). In all analyses, the sample is restricted to the employedFootnote 7 population of the Paris Metro area living in ordinary non-institutional households. Income inequality measures using EDP-DADS are calculated for full-time male employees aged 25–55.Footnote 8

4 Results

4.1 Changes in Occupational Structure and Inequality

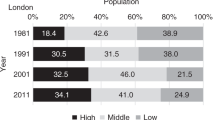

Three important changes have occurred in the composition of the Paris Metro area population since 1990: a sharp increase in top occupational groups, a growing number of immigrants, and rising income inequality. Figure 17.2 shows the change in the occupational structure of the area over time. While the middle class has remained relatively stable, the top occupational group climbed from 20 to 29% of the population while the bottom group declined by 8 pp. Compared to the national average, in 2015, the Paris region stands out with markedly more top occupational groups (29 vs 17% nationally) and fewer lower status groups (22 vs 14% nationally). Overall, this evidence of an upward socioeconomic shift with an increased share of top and top-middle occupational groups is consistent with the process of professionalisation described for the previous decades by Préteceille (1995) for Paris and by Hamnett (1994, 2001) for London. As we do not find increases both at the top and bottom of the distribution, our results are inconsistent with the thesis of social polarisation (Sassen 1991).

The Paris metro area has also experienced an increase in the immigrant population. Between 1990 and 2015, the share of immigrants grew by 5 pp., reaching 23% in 2015, while the share of non-European immigrants increased from 9% in 1990 to 17% in 2015, which was more than twice the national average. However, changes in the occupational structure of the immigrant population differ strongly from the overall population. Immigrants, unlike natives, did not experience a strong increase at the top of the occupational distribution. Rather, the middle group grew from 42 to 59% between 1990 and 2015 while the bottom group declined. This trend seems to be driven primarily by the entry of immigrants into the service sector, which increased by 7% between 1990 and 2015.

Income inequality dynamics have also evolved in relation to these compositional changes. According to the GINI index, levels of inequality appear to be quite stable at 0.36, consistent with prior findings (Verdugo 2014). However, wage percentile ratios indicate rising inequality. In 2015, the top 1% earned 11 times the wages of the first decile, which is an increase of one point since 1990 and 4 points higher than the national average. Changes in income inequality thus appear to reflect rising wages among top earners.

Finally, it is of note that the increasing presence of the upper classes in the Paris metro area resonates with changes in housing tenure. Homeownership rates in the area, though lower than the national average, grew by 4 pp. reaching 47% in 2015, while renting on the private market dropped to 31%. Social housing occupancy remained relatively stable at 22%.

4.2 Residential Patterns of Occupational Groups in the Paris Metro Area

We now turn to explore the spatial distribution of occupational groups in Figs. 17.3, 17.4 and 17.5. All maps show a concentration of the top occupational groups in the western neighbourhoods of the city of Paris as well as the western suburban departments of Hauts-de-Seine and Yvelines. In contrast, the upper classes are largely under-represented in the northern neighbourhoods of Paris and the northern and eastern departments of Seine-Saint-Denis and Val de Marne, areas where a strong presence of bottom occupational groups is found (Fig. 17.3). Yet despite this evidence of spatial polarisation between the top and bottom groups, the Paris metro area is still largely composed of middle or mixed neighbourhoods, as illustrated by Fig. 17.4. Further, neighbourhoods in the Paris metro area are characterised more by the concentration of affluence than the concentration of disadvantage. While there are indeed places where the bottom occupational groups are overrepresented (Fig. 17.3), there are almost no neighbourhoods where the share of this group exceeds 60% (Fig. 17.4). On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 17.4, neighbourhoods where the top dominate are more frequent.

Further, comparing the maps overtime points to a clear intensification of the spatial divide between the top and bottom groups between 1999 and 2015. As Fig. 17.4 best illustrates, the number of top and polarised top neighbourhoods in Paris and its western suburbs increased substantially over time. This process of gentrification is clearly visible in the city of Paris, which in 2015 was mostly composed of upper-class neighbourhoods, with the exception of the northern and some western parts of the city. Top occupational groups have also expanded their presence in the Eastern department of Seine et Marne and the southern department of Essonne, which, although relatively middle class, have more upper-class neighbourhoods in 2015 compared to 1999 (Fig. 17.5). The increase of top occupational groups in the Paris metro area was thus accompanied by spatial transformations linked to gentrification and a greater concentration of affluence.

4.3 Occupational and Immigrant Segregation

These structural and spatial trends suggest that socioeconomic segregation may be on the rise in the Paris metro area. Dissimilarity indexes for occupational groups are presented in Tables 17.1 and 17.2. First, no matter the year, the highest levels of segregation are observed between the top and bottom occupational groups. Moreover, the index for these groups increased slightly over the period from 0.47 to 0.49. Thus, in 2015, about half of the top occupational groups would have to change neighbourhoods for the population distribution to match that of the broader metro area. This level of segregation between the top and bottom groups is higher than the national average of 0.45. Further, looking at the more detailed occupational categories, the highest indexes are found between managers and professionals versus unskilled workers, machine operators but also middle-status groups such as clerks. Indexes for the top versus middle and middle versus bottom groups are, in contrast, lower and relatively stable over time. The index between the top and middle grew from 0.31 to 0.32 between 1990 and 1999, while the index between the middle and bottom declined from 0.22 to 0.21 between 1999 and 2015.

We further calculated interaction indexes to measure exposure or the degree to which occupational groups share the same residential spaces. While the dissimilarity indexes are relatively stable, changes in the interaction indexes point to the increasing isolation of the top occupational groups over time. In 1990, for an individual working in a bottom occupation, the average share of high-status individuals within the same neighbourhood was 37%; in 2015, it fell to 23%. Exposure also dropped by 8 pp. between the top and middle groups. Hence, as suggested earlier by the maps, changes in socioeconomic segregation are linked to an intensified concentration of the most affluent groups within specific neighbourhoods.

Turning to immigrant segregation, levels of segregation between immigrants and French natives are lower overall than occupational segregation and quite stable overtime at 0.26. Between non-European immigrants and natives, the index is much higher and more comparable to the separation of top versus bottom occupational groups, at 0.37 in 1990. Yet, the data suggest that non-Europeans are becoming less segregated from natives over time, as dissimilarity indexes for this group fell by 5 pp. over the period. This trend may be spurred by the shift upward from bottom to middle occupations among immigrants discussed earlier. Again, however, the interaction indexes nuance this picture. Indexes for natives versus immigrants and non-Europeans are high, indicating a relatively strong degree of contact within neighbourhoods, due to the large share of natives. However, the probability of interaction also declines significantly over time, by 6 p.p. for the exposure of immigrants to natives and 8 p.p. for non-Europeans versus natives. In 2015, interaction indexes are 0.73 and 0.71 for Non-Europeans and immigrants, respectively. Thus, the immigrant population appears to be residing more and more in areas with fewer natives.

Our final analysis aims to assess the extent to which socioeconomic and immigrant segregation are correlated in the Paris metro area. Do lower-class, disadvantaged neighbourhoods have higher concentrations of immigrants, and if so, has this correlation weakened or intensified over time? Panel A in Table 17.3 shows cross-sectional correlations between the share of occupational groups, unemployment rates and immigrant shares of neighbourhoods in the area. In both 1999 and 2015, greater shares of immigrants are strongly positively correlated with the share of bottom occupational groups and high unemployment rates in neighbourhoods. On the other hand, the presence of immigrants—especially of non-European origin—is negatively linked with the share of top occupational groups. Interestingly, however, while the share of immigrants in neighbourhoods was negatively correlated with the presence of middle groups in 1999, this correlation turned positive—if still weak—in 2015.

All in all, the correlation between immigrant-dense and low-SES neighbourhoods become markedly stronger between 1999 and 2015. This is confirmed in panel B in which we report the correlations between the changes in shares of immigrants, low and high-status groups and unemployment rates in neighbourhoods between 1999 and 2015. Clearly, neighbourhoods that experienced an influx of immigrants or non-European immigrants saw a significant reduction in the shares of high-status groups, an increase in unemployment and a rise in the share of low-status occupations. While not causal, these patterns suggest that immigrant neighbourhoods tend to increasingly concentrate disadvantage along with a “flight” of the upper classes from these spaces.

5 Conclusion

This chapter explored changes in occupational structure, income inequality and immigration in the Paris metro area between 1990 and 2015 and ways in which these changes shaped the spatial divide between socioeconomic groups and immigrants and natives. We find that a shift to the top of the occupational distribution occurred in recent decades with a substantial increase in the share of top occupations and a drop in low-status groups. Income inequality also grew over the period, driven by rising wages among the top 1% earners.

At first glance, residential segregation between occupational groups appeared to change only marginally in conjunction with these evolutions. Dissimilarity indexes remained quite stable, with only a small increase observed between the bottom and top occupational groups. Segregation further appeared to decrease slightly between middle and bottom occupations. However, the dissimilarity indexes mask increasing spatial homogeneity over the period, as interaction indexes reveal that the upper classes have become substantially less likely to share the same neighbourhoods with other groups. In line with this lower degree of contact between SES groups, the maps showed an expansion of high-status neighbourhoods in the Western suburbs of Paris and the city centre. These trends align with evidence of gentrification and the growing spatial isolation of the upper classes highlighted in previous studies (Préteceille 2006; Godechot 2013; Ribardière 2019), and lend support to the hypothesis that income inequality, likely related to the expanding financial sector (Godechot 2013), has contributed to the intensification of socioeconomic residential segregation in the Paris area.

We further investigated changes in the residential segregation of immigrants and its relation to socioeconomic segregation. The findings show that segregation is highest between Non-Europeans and natives, much stronger than levels of segregation for immigrants overall and for most occupational groups. Further, although dissimilarity indexes remained stable or dropped somewhat between immigrants and natives, interaction indexes again revealed decreasing contact between these groups within neighbourhoods over time. Moreover, while immigrants have entered the middle occupational groups over the period, the correlation in neighbourhoods between low socioeconomic status, high unemployment and the presence of immigrants is strong and growing. These trends may reflect the effects of discrimination or native flight processes—especially among the upper classes—which consolidate disadvantage within neighbourhoods that have high shares of immigrants. Overall, socioeconomic and immigrant segregation are tightly correlated, and increasingly so over time.

A limitation of our analysis is that we do not observe second-generation immigrants. Descendants of immigrants who are not living with their parents are not identified as such in the census and are thus counted as French natives. It is possible that the stability and even decline in the dissimilarity indexes between Non-European immigrants and natives masks an increase in the share of second-generation immigrants in the neighbourhood. This would coincide with prior research that shows similar levels of residential segregation and disadvantage for second generations compared to their parents (McAvay 2018a, b; McAvay and Safi 2018). While plausible, this claim should be nuanced by the fact that second generations of non-European origin living independently from their parents accounted for about 3% of the French population in 2015 (Brutel 2017).

All in all, it is notable that, as prior research has highlighted, the intensification of spatial inequalities documented here is at odds with recent French urban policy initiatives that have explicitly sought to curtail socioeconomic segregation, particularly by renewing disadvantaged urban areas to attract middle and upper-class households (Lelévrier 2010; Epstein 2011; Fol 2013). As the Paris area becomes more gentrified and wages are rising among the wealthiest households, the upper classes are better able to implement strategies to avoid poor or ethnoracially diverse areas, while prohibitive housing prices and discrimination keep poor households and immigrants out of upper-class neighbourhoods. It also seems likely that the conjunction of socioeconomic disadvantage and the presence of immigrants within neighbourhoods will reinforce white flight and avoidance processes as these areas become stigmatised both due to their class and ethnic composition. At the same time, the reduced social and residential mobility prospects of people living in poor areas, particularly minorities, compounds socio-spatial inequalities. Rather than investing in costly transformations of targeted urban neighbourhoods, more effective redistributive policymaking might aim at favouring social mobility opportunities among minorities and disadvantaged groups.

Notes

- 1.

We use the entire Ile de France region and census tracts of about 2,500 inhabitants, whereas the major prior study on socioeconomic segregation focused on the city of Paris only using larger tracts (Préteceille 2006) due to data availability constraints.

- 2.

This framing of segregation as predominately a problem of class can be at least partly understood in light of the Republican colorblind model and the Marxist tradition in the French social sciences. France considers distinctions on the basis of race/ethnicity to be illegitimate and therefore does not collect ethnic/racial statistics, creating significant barriers to measuring racial residential segregation or other inequalities. At the same time, the predominance of Marxism within French sociology hindered enquiry into the ethnoracial dimensions of stratification beyond social class mechanisms (Safi 2013).

- 3.

Specifically, the creation of priority educational zones (‘ZEP’) in 1981, followed by sensitive urban zones (‘ZUS’) in 1996.

- 4.

L’échantillon démographique permanent in French. EDP is a large scale panel that has been conducted by the French National Institute of Statistics since 1968 on the basis of census declarations and civil registries.

- 5.

An alternative would have been to use the urban area (aire urbaine) of Paris estimated by the French statistical institute and which is based on daily commuting patterns. Because it is revised periodically and has changed over the period, we preferred using the region that has stable boundaries. In practice, using either definition would have little effect on the results as the region includes 97% of the population of the urban area in 2013 and 99.9% of the population of the region is included in the urban area.

- 6.

In French, the categories are as follows: top (chefs d’entreprise, professions libérales, cadres); middle (professions intermédiaires, techniciens, contremaîtres, agents de maîtrise, employées, personnels des services, artisans, commerçants et assimilés); bottom (ouvriers qualifiés, ouvriers non qualifiés).

- 7.

This excludes inactive, retired and unemployed persons. Agricultural workers are further excluded given the small N for this category.

- 8.

We focus on male employees in order to avoid the comparisons of the evolution of income inequality affected by the increase in the labor force participation of women, which was substantial over the period.

References

Bonnet F, Lalé E, Safi M, Wasmer E (2016) Better residential than ethnic discrimination! Reconciling audit and interview findings in the Parisian housing market. Urban Stud 53(13):2815–2833

Bourgeois M (2013) Choisir les locataires du parc social? Une approche ethnographique de la gestion des HLM. Sociol Du Travail 55(1):56–75

Bunel M, l’Horty Y, Du Parquet L, Petit P (2017) Les discriminations dans l’accès au logement à Paris: une expérience contrôlée ⟨halshs-01521995⟩

Brutel, C. (2017). Etre né en France d’un parent immigré: Une population diverse reflétant l’histoire des flux migratoires (Insee Première No. 1634). L’Institut National de la Statistique et desÉtudes Économiques, Paris, France

Epstein R (2011) Politiques de la ville: bilan et (absence de) perspectives. Regards Croisés Sur l’économie 1:203–211

Fol S (2013) La politique de la ville, un outil pour lutter contre la ségrégation? L’inf Géogr 77(3):6–28

Gobillon L, Magnac T, Selod H (2011) The effect of location on finding a job in the Paris region. J Appl Econ 26:1079–1112

Godechot O (2013) Financiarisation Et Fractures Socio-Spatiales. L’année Sociol 63(1):17–50

Hamnett, C. (1994). Socio-economic change in London: professionalization not polarization. Built Environ 192–203.

Hamnett C (2001) Social segregation and social polarization. Handbook of urban studies, pp 162–176

Kirszbaum T, Simon P (2001) Les discriminations raciales et ethniques dans l’accès au logement social

Labrador J (2013) Une forte hétérogénéité des revenues en Ile-de-France. Ile-de-France à la page. N. 414. INSEE

Lelévrier C (2010) La mixité dans la rénovation urbaine: dispersion ou re-concentration? Espaces Et Sociétés 1:59–74

Lelévrier C, Melic T (2018) Impoverishment and social fragmentation in housing estates of the Paris region, France. In: Hess DB, Tammaru T, van Ham M (eds) Housing estates in Europe: poverty, ethnic segregation and policy challenges. Springer.

Massey DS, Denton NA (1993) American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press.

Maurin E (2004) Le ghetto français. Enquête sur le séparatisme social, Paris, Le Seuil

McAvay H (2018a) How durable are ethnoracial segregation and spatial disadvantage? Intergenerational Contextual Mobility in France. Demography 55(4):1507–1545

McAvay H (2018b) The ethnoracial context of residential mobility in France: Neighbourhood out-migration and relocation. Population, Space and Place 24(6):e2138

McAvay H, Safi M (2018) Is there really such thing as immigrant spatial assimilation in France? Desegregation trends and inequality along ethnoracial lines. Soc Sci Res 73:45–62

Pan Ké Shon JL, Verdugo G (2015) Forty years of immigrant segregation in France, 1968–2007. How different is the new immigration?. Urban Stud 52(5):823–840

Petit P, Bunel M, Ene E, L’Horty Y (2016) Effets de quartier, effet de département: discrimination liée au lieu de résidence et accès à l’emploi. Revue Économique 67(3):525–550

Preteceille E (1995) Division sociale de l’espace et globalisation: le cas de la métropole parisienne. Sociétés Contemp. 22(23):33–67

Préteceille E (2006) La ségrégation sociale a-t-elle augmenté : la métropole parisienne entre polarisation et mixité. Sociétés Contemp, no 62:69–93

Préteceille E (2009) La ségrégation ethno-raciale a-t-elle augmenté dans la métropole parisienne? Revue Française De Sociol 50(3):489–519

Quillian L, Lagrange H (2016) Socioeconomic segregation in large cities in France and the United States. Demography 53(4):1051–1084

Rathelot R, Safi M (2014) Local ethnic composition and natives’ and immigrants’ geographic mobility in France, 1982–1999. Am Sociol Rev 79(1):43–64

Reardon SF, O’Sullivan D (2004) Measures of spatial segregation. Sociol Methodol 34(1):121–162

Reardon SF, Bischoff K (2011) Income inequality and income segregation. Am J Sociol 116(4):1092–1153

Ribardière A (2019) Les territoires populaires du Grand Paris: entre paupérisation, gentrification et moyennisation. Métropolitiques, 18 février 2019. https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Les-territoires-populaires-du-Grand-Paris-entre-pauperisation-gentrification-et.html.

Sala Pala V (2013) Discriminations ethniques. Rennes (Presses universitaires de), Les politiques du logement social en France et au Royaume-Uni

Safi M (2009) La dimension spatiale de l’intégration: évolution de la ségrégation des populations immigrées en France entre 1968 et 1999. Revue Française De Sociologie 50(3):521–552

Safi M (2013) Les inégalités ethno-raciales. Découverte (La).

Sassen S (1991) The global city: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Tabard N (1993) Des quartiers pauvres aux banlieues aisées: une représentation sociale du territoire. Economie Et Statistique 270(1):5–22

Verdugo G (2011) Public housing and residential segregation of immigrants in France, 1968–1999. Population 66(1):169–193

Verdugo G (2014) The great compression of the French wage structure, 1969–2008. Labour Econ 28:131–144

Verdugo G, Toma S (2018) Can public housing decrease segregation? Lessons and challenges from non-european immigration in France. Demography 55(5):1803–1828

Watson T (2009) Inequality and the measurement of residential segregation by income in American neighborhoods. Rev Income Wealth 55(3):820–844

Whitehead CM, Scanlon K (2007) Social housing in Europe. London School of Economics and Political Sciences

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

McAvay, H., Verdugo, G. (2021). Income Inequality and Segregation in the Paris Metro Area (1990–2015). In: van Ham, M., Tammaru, T., Ubarevičienė, R., Janssen, H. (eds) Urban Socio-Economic Segregation and Income Inequality. The Urban Book Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64569-4_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64569-4_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-64568-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-64569-4

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)