Abstract

An ethical and forward-looking health sector response to sex work aims to create a safe, effective, and non-judgemental space that attracts sex workers to its services. Yet, the clinical setting is often the site of human rights violations and many sex workers experience ill-treatment and abuse by healthcare providers. Research with male, female, and transgender sex workers in various African countries has documented a range of problems with healthcare provision in these settings, including: poor treatment, stigmatisation, and discrimination by healthcare workers; having to pay bribes to obtain services or treatment; being humiliated by healthcare workers; and, the breaching of confidentiality. These experiences are echoed by sex workers globally. Sex workers’ negative experiences with healthcare services result in illness and death and within the context of the AIDS epidemic act as a powerful barrier to effective HIV and STI prevention, care, and support. Conversely positive interactions with healthcare providers and health services empower sex workers, affirm sex worker dignity and agency, and support improved health outcomes and well-being. This chapter aims to explore the experiences of sex workers with healthcare systems in Africa as documented in the literature. Findings describe how negative healthcare workers’ attitudes and sexual moralism have compounded the stigma that sex workers face within communities and have led to poor health outcomes, particularly in relation to HIV and sexual and reproductive health. Key recommendations for policy and practice include implementation of comprehensive, rights-affirming health programmes designed in partnership with sex workers. These should be in tandem with structural interventions that shift away from outdated criminalized legal frameworks and implement violence prevention strategies, psycho-social support services, sex worker empowerment initiatives, and peer-led programmes.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

I felt so humiliated. I felt that I hated myself. I was crying. My eyes were full of tears throughout walking towards the [public health] clinic that I was referred to. Because of the way that the nurse [at the general hospital] shouted at me. I didn’t know what I did wrong by coming to the clinic for a consultation […]

So, in that way if sex workers continued to be treated in this way; it drives them away [from healthcare facilities]. It drives them away—Penelope ZuluFootnote 1 (female sex worker, aged 45, inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa)

Introduction

In 1993, one of South Africa’s academic health journals, the South African Medical Journal, published an article entitled “Prevention of sexually transmitted disease. The Shurugwi sex-workers project” [1]. While this article describes an intervention that is more than 30 years old and which was limited to a small rural town in sub-Saharan Africa, it unfortunately reflects contemporary features of the health sector’s general approach to sex workers and to sex work in many areas of the world. This work described a 1988 health intervention that took place in a small mining town in the Midlands province of Zimbabwe, in which sex workers were framed as “a reservoir and transmission of sexually transmitted disease (STDs) ”in Zimbabwe. The project—called the Shurugwi experiment—included the formation of an STD Committee consisting of health workers that “resolved at its first meeting that all sex-workers in the town should convene a general meeting. The sex-workers were then given a lecture on STDs and their possible complications, especially for women” and were subsequently warned about “becoming reservoirs and spreaders of STDs”. Sex workers were requested to form their own committee that would work with the STD committee. The author noted:

At the general meeting, it was also resolved that a card system for sex-workers would be introduced. To qualify for the card, a sex-worker had to undergo a physical examination by the medical officers in the committee. Those who required psychiatric counselling, e.g. for AIDS pre-testing, were referred to the nurse responsible. No sex-worker could enter a beer garden, where most clients are available, without the health card. Since all beerhalls are manned by security guards, these were informed of the committee's resolution […] The card holders were examined on a monthly basis. A special government stamp was put on the cards of those free from disease. Those found to have a disease had their cards withdrawn until such time they were free from disease […]. The researcher gave lectures on STDs and their complications in all beerhalls… ([1], p. 40)

Unfortunately, the intervention described in, and the content and tone of, the above publication [1] did not recognise sex workers or sex workers’ health as having intrinsic value—and in many ways this context has hardly changed. Moreover, the fraught setting of sex work and the oppressive context in which the above HIV/STI prevention project took place in 1988 in Zimbabwe still persist today. While it would seem to be understood that if sex workers were diagnosed with an infection, they would be referred for treatment, no details or reference to treatment was described as part of the intervention. Rather, the approach appeared to be strongly underpinned by themes of blame, the need for compulsory policing, reprisal, and “lectures”, as well as moral superiority. Similarly, the intervention had been imposed in a top-down manner, contained very little incentives, and did not respect sex worker agency or autonomy. While the author concluded the article by calling for law reform (in this case in the form of legalisation) and recommended that sex workers be consulted in the planning of prevention programmes, no evidence was provided that sex workers had, in fact, any input on either the programme or the resolutions taken on how to manage their health, work, or well-being.

In this chapter, we aim to describe contemporary sex worker experiences with health services and the health system in Africa as documented in the literature and supported by sex workers’ lived experiences. We will highlight how stigma, discrimination, and sexual moralism impact on health workers’ engagement with sex workers and their families, and how this inhibits sex workers from keeping themselves safe and healthy. We will conclude with an encouraging example from South Africa where the Department of Health, in partnership with civil society, has taken leadership in rolling-out specialised services for sex workers to proactively address healthcare worker prejudices, and to provide health care for sex workers that is respectful and participatory.

Sex Work and Health in Africa

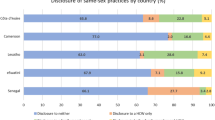

Much of the research on sex work in Africa describes the perilous position of sex workers, and usually relates it to poor health outcomes and, in particular, to HIV transmission. The dangers that African sex workers face are by no means unique, and criminalisation and an oppressive legal system, high levels of violence, repressive law-enforcement, dangerous clients, and a prejudiced public constitute challenges that sex workers face on all continents. Yet, in many African countries these challenges are particularly severe due to a number of interlocking factors including the following: sex work is strongly stigmatised from religious, cultural, and gender perspectives; extreme levels of poverty combined with the lack of adequate social safety nets push many women into the informal sector, which includes exchanging sex for resources; healthcare and social services are under resourced; there is little legal recourse for human rights violations; and sex worker collectivisation did not begin to gain much momentum until 2009, with the formation of the African Sex Worker Association (ASWA) [2]. In fact, the criminalisation of adult consensual sex is a popular strategy adopted by many of the 55 states on the African continent. The vast majority of countries in Africa criminalise some aspects of sex work [3, 4]. Same-sex practices are criminalized in 33 countries, with the death penalty still applicable in Mauritania, Sudan, Northern Nigeria, and Southern Somalia [5], and between 27 and 30 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa criminalise aspects of HIV [6, 7]. The far-reaching, negative consequences of using the blunt tool of the criminal law to regulate adult consensual sexual behaviour has been well-documented—particularly so within the literature on HIV [8]. The health system and healthcare workers are often first responders, required to meet the recurring support and care needs of individuals who are directly affected by these criminal laws and their concomitant stigmatisation and violence; thus they are in an important position to document these issues [9] and be vocal patient advocates.

A recent systematic review of healthcare services for female sex workers in Africa found that these were limited in coverage, included only a narrow scope of services, and were poorly coordinated [10]. Health programmes associated with sex work were specialised and mostly focused on HIV and STIs rather than providing comprehensive health services, including sexual and reproductive health. In fact, contraception was only available in 7 sites out of the 54 found in the systematic review. Only 6 of them offered urine pregnancy tests and not one of the sites offered termination of pregnancy services (a number of African countries criminalise termination of pregnancies) [11]. The funding of all the sites was provided by international donors, not by governments, and the focus was research-driven rather than the implementation of much-needed, large-scale service-delivery programmes.

Disappointingly, the review also noted that there were few structural interventions targeting the sex work context. The structural interventions documented included gender-based violence services in only two countries (Zambia and South Africa); one project that provided legal literacy (South Africa); and one facility teaching violence prevention techniques such as the development of personal plans to reduce risk (South Africa). For example, in Zambia, local clinics would arrange referrals for legal assistance as part of gender-based violence interventions. Limited programmes in Malawi and Kenya included micro-enterprise to support additional income generation for sex workers.

The findings of the systemic review are deeply distressing, against a backdrop in which more than a third of female sex workers in Sub-Saharan Africa (37%) are living with HIV [10]. This is three times the global HIV prevalence among female sex workers [10]. Unaddressed HIV risk has led to large-scale illness and death, as well as increased stigmatisation and human rights violations among the various sex work communities in Africa. One modelling study suggested that, of the 106,000 deaths from HIV in 2011 linked to female sex work globally, 98,000 occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa [12]. Clear, rigorous scientific evidence [13,14,15,16] and a long history of calls by sex workers and allies support expansion of interventions to support the health, well-being, and rights of sex workers and to mitigate HIV [17,18,19]. Among these are the removal of criminal laws surrounding sex work, scaling up of treatment, prevention and care programmes, and violence prevention and stigma reduction programmes. Yet these are not being implemented, or at best, are not implemented to scale. It is also very troubling that, despite far-reaching inroads into the AIDS epidemic globally [20], HIV rates among female sex workers at a global level remain “largely unchanged” today [15]. Finally, HIV data on transgender and male sex work as well as on sex work clients—groups which have traditionally been overlooked—remain scant but are increasingly being collected [15]. It is vital that this research is expanded to inform programmes and services that serve these groups and to address their particular needs and concerns.

How Do Sex Workers Experience Existing Healthcare Services?

Moving from country-level to individual-level, we now turn to exploring how sex workers in Africa experience the healthcare services available to them. A range of problems have been documented, and the paternalism and stigma described in the opening paragraph of this chapter unfortunately still characterise how some healthcare services approach sex workers and the sex work context.

The issues of discrimination and prejudice remain key themes in sex workers’ interactions with health care, and healthcare settings are, alarmingly, still a significant site of human rights violations [21]. Research with male, female, and transgender sex workers in Uganda, South Africa, Kenya, and Zimbabwe, for example, has documented a range of problems experienced by sex workers within healthcare settings: poor treatment, stigmatisation, and discrimination by healthcare workers; having to pay bribes to obtain services or treatment; being humiliated by healthcare workers; and, the breaching of confidentiality [22, 23].

Conservative beliefs held by healthcare workers combined with the deeply unequal power differentials between healthcare workers and sex workers often result in the latter being particularly poorly treated. Some sex workers report avoiding healthcare services as much as possible rather than to be subjected to prejudice and disrespect. It should be noted that healthcare worker approaches to sex work are shaped by broader societal, cultural, and religious beliefs bolstered by the criminalisation of sex work. Structural reform including the decriminalisation of sex work and addressing the stigma that attaches to sex work is a vital component of the social change necessary to support sex worker health and well-being, which will, in turn, shape positive and empathetic healthcare worker approaches.

Let us look at specific examples:

At the first African Sex Worker conference in 2009, delegates from different countries spoke about sex workers’ experiences with health services. The country representative from Malawi noted a colleague’s experience with seeking ARV treatment in a hospital in Zomba, who had received the following response from a nurse:

Why do you bother us? It’s better for people like you to die. Why should the government waste money treating people like you rather than giving the medication to important people? ([2], p. 12)

The notion that sex workers are undeserving of services or treatment, and the experience of healthcare workers bluntly articulating offensive views that sex workers should rather be dead than treated, are also described in Scorgie’s study, where a sex worker in Uganda related:

We are despised in the hospitals. They [healthcare providers] say, “We don’t have time for prostitutes” and they also say that if one prostitute dies then the number reduces. (Belinda, 27-year-old female, Kampala) ([23], p. 6.)

Delegates at the African Sex Worker conference from Botswana and Zimbabwe also noted the intense hostility and discrimination on the part of healthcare workers. Examples cited from Botswana included breaches of privacy and medical ethics, such as conducting HIV testing without consent. Scorgie and colleagues documented forced HIV testing or HIV testing without the patient’s knowledge in two clinical sites in South Africa and one in Uganda. In contrast, some participants in the same study noted that they were denied HIV testing when they had requested it.

Binagwaho related the experience of a female sex worker in Rwanda who noted that she was refused treatment reputedly because of personal vindictiveness or jealousy on the part of healthcare workers:

I live in the center of town, where most health workers live, and I run into them all the time. [At the clinic,] if they know you haven’t given up prostitution, they can refuse to serve you, because they suspect you’ve been with their husbands. They keep grabbing other people’s files and passing you over, because you’re a prostitute. ([24], p. 92)

Sex workers have noted how healthcare workers have interrogated them unnecessarily about sexual practices, while male and transgender sex workers, in particular, have been held up as curiosities by staff. Boyce’s study with male sex workers noted how participants have been publicly humiliated:

Nurses often call each other when they find out about being a male sex worker saying: “we have never had such a case” or “come look at what his type of STD, we have never had it at this hospital before” ([25], p. 20)

Following a gang rape by clients, a transgender participant in the Scorgie study painfully described the secondary victimisation by healthcare workers in the following way:

I go to report to the police, they told me to go to the hospital and I was still wearing my jeans, wig and with my breasts. When the doctor examined me and find out that I am a she-male, he called other doctors and nurses. They left their work to come and see that a man got raped. It was like a mockery…. The doctor told me I was not raped but I was sodomised because I am a man. The way I was dressing they said “what kind of a woman [are you]?” I just walked [away] from the hospital without being treated. It was not fair because I was raped the whole night. ([23], p. 6)

Transphobia, homophobia, and xenophobia often overlap and strengthen prejudices toward sex work, and some of these dynamics are described by Boyce and Isaacs as “intercommunity hostility” ([26], p. 300). Xenophobia, racism, migration status, homelessness, gender identity, sexual orientation, and drug-use are all factors that can compound discrimination in the healthcare setting, and leave populations that are often most in need of social, legal, and wellness support without services, thus ultimately compounding their marginalisation.

Sex workers often report that they would rather avoid health care than expose themselves to additional stigmatisation or rights violations. Alternatively, they may choose not to inform healthcare workers that they are sex workers, which Scorgie points out could lead to sub-optimal medical treatment. In a study by Fobosi and colleagues on truck-stop clinics in South Africa, sex workers articulated this reticence as being “shy” about seeking treatment at public hospitals [27]. Sex workers who register their “shyness” seem to distort the problem of healthcare avoidance as an individual failing or a personal lack of assertiveness, rather than placing the focus on broader systemic issues within health and society.

Some healthcare workers’ attitudes toward sex work are informed by conservative and religious perceptions of sex work—views that often label sex worker livelihoods as immoral. Baleta relates an experience of a female sex worker in Lesotho who was refused treatment for a badly infected wound on her leg in the following way:

She had her leg bandaged at the hospital but the health-care providers accompanying her informed staff that she was a sex worker, which was recorded on her health card. The doctor’s response was, ‘Well you are a sex worker, you are going to die in the next 3 months. There is nothing more we can do for you, and I have a waiting room full of people who are not morally corrupt like you’ and sent her home. ([28], p. e1)

These distressing attitudes manifest not only in the provision of medical treatment to sex workers, but also limit the reach and effectiveness of other services and supports, including psycho-social support, disease prevention, and health promotion. In some healthcare settings where male condoms are provided free-of-charge, sex workers reported only being allowed to take a few condoms each, or alternatively, being expected by unscrupulous healthcare workers to trade sex or money for the allegedly free condoms [23, 29]. Some healthcare workers erroneously believe that by providing condoms to sex workers, they are “promoting” sex work—an assumption in line with early opposition to making free condoms available to youth because, rather than reducing their HIV risk, it would simply increase their sexual activity. Research has thoroughly debunked this argument [30, 31].

Conservative attitudes about sexual and relationship constellations also manifest in healthcare worker insistence that female sex workers bring their husbands or sexual partners along to the clinic. Otherwise they will not provide treatment to sex workers. Scorgie quotes a 25-year-old female sex worker from Kampala who said:

When you go to the hospital the health workers say, “We will not treat you unless you come with your husband”. We don’t have husbands, so we go to drug shops and buy some drugs to relieve us from the pain. ([23], p. 6)

While research on sex workers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour beyond the public health sector is limited, some studies mention sex worker self-treatment: purchasing over-the-counter remedies from pharmacies, seeking services in the very expensive private sector and/or consulting with traditional healers [10, 23, 25]. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some sex workers experience traditional healers as less judgemental than healthcare workers. A respondent in the Scorgie study noted that:

It’s tough, especially when you suffer from an STI, they treat you like you just got what you deserve, and we end up using some traditional herbs because the traditional healers don’t ask too many questions. (Thuli, 35-year-old female, Bulawayo) ([23], p. 10)

An under-explored issue is how sex workers’ negative experiences in the healthcare settings may impact on their family members’ access of these services. Sex worker avoidance strategies may include a reluctance to bring their children or adult dependents to health facilities, leading to poor health outcomes, not just at the individual level but at the family level, too. Scorgie notes that:

Discriminatory treatment was applied even at times to family members of sex workers who accompanied them to health facilities. One participant recounted being pushed to the end of the queue when bringing her child for treatment and was attended to only after all other patients had been seen ([23], p. 10).

Significantly, while many sex workers support dependents, including children, the systematic review by Dhana and colleagues found only one general clinic in Uganda that specifically offered health care for the children of female sex workers [10].

In addition to documented concerns regarding negative treatment by healthcare workers, the prejudices of non-clinical staff employed in health systems, such as receptionists, security guards, cleaners, porters, and administrators, also contribute to sex worker mistrust, fear, and avoidance of healthcare facilities. This, however, is often overlooked as a barrier to services. A 2018 study in South Africa on access to health care for Key Populations noted the following:

[…] it was widely reported that health facility staff express stigmatising attitudes towards key populations. Although these were said to occur from all cadres of staff, a majority of assessment participants singled out non-clinical staff, especially security guards, but also clerks and cleaners, as the most problematic; one reason being that they are rarely, if ever, involved in training and sensitisation activities provided for their clinical colleagues. Research findings bolster these observations, particularly for MSM [Men who have sex with Men] and for foreign migrants (Rispel et al., 2011; Vearey, 2014). As a further example, peer educators working with PWID [people who inject drugs] described how their clients are frequently barred from facilities by security guards, either because of their appearance or because it has become known that they are a PWID. ([32], p. 23)

In view of the fact that non-clinical staff often serve as gate-keepers to health care, it is vital that they are routinely included in sensitivity training.

The Power of Positive Experiences

Studies documenting sex worker experiences within healthcare services also describe positive and encouraging engagements with health care although these tend to be the minority of experiences. Respondents in the Scorgie study spoke about some healthcare workers as being “friendly and respectful”, having a “good attitude” and as affirming sex workers’ dignity [23]. This has been well documented, for example, in sex work-specific clinics where staff have received sensitisation training, such as in inner-city Johannesburg [33,34,35]. The Fobosi study on roadside wellness clinics recorded sex worker respondents’ satisfaction with “friendly staff”, how some clinics were open at night time and even included services that users didn’t expect, like malaria screening [27]. The opening quote of this chapter includes a description of Penelope Zulu’s painful experience with harsh healthcare staff when she went to a health facility for a general check-up. However, her narrative changes when she is referred to a sex work-specific clinic, where an empathetic and kind nurse provided the clinical care and emotional support that she needed. Zulu describes the nurse as “being like a mother”; under her support and mentorship, Zulu decided to become a peer educator and ultimately became an outspoken leader in the sex worker movement in South Africa.

South Africa has seen some unique developments on HIV and sex work. In 2016, South Africa became one of the first countries in the world to pass a sex work-specific HIV plan [36]. This was due to factors including a staggeringly high HIV prevalence associated with the sex work context, the health system’s commitment to a rights-based approach to HIV/AIDS, the positive experiences of sex workers at the few sex work-specific clinics available, and the uncompromising activist approach by sex worker advocates and allies [36,37,38]. The “South African National Sex Worker HIV Plan, 2016–2019” is comprehensive in its strategy. It adopts a combination prevention approach that includes peer-education-led strategies and makes specific provision for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Universal Test-And-Treat while also endeavouring to deal with social and structural drivers of HIV in the lives of sex workers [21]. It supports the decriminalisation of sex work, while committing itself to “competency and sensitisation training to health and social workers. Training should also be expanded to law enforcement officials, other service providers, and the community”. ([39], p. 29). More recently, South Africa’s “National Strategic Plan on Gender-based violence & Femicide” included a commitment by government to finalise the “legislative process to decriminalise sex work” by March 2024 [40]. These policies emphasize the key linkages between health and violence, and the structural reforms necessary to safeguard sex worker dignity and rights.

At the time of writing, the HIV Plan was being reviewed and its implementation assessed. While it is impossible to address deep-seated prejudices and other structural barriers to health care with quick fixes, the Plan and its comprehensive approach is an influential first step in the right direction. Indeed, in a recent submission to the United Nation’s Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on South Africa, Human Rights Watch noted the following:

On a positive note, the sex workers we interviewed told us they had free, fairly straightforward, and non-discriminatory access to health care, including reproductive health care and HIV/AIDS treatment. Many remarked on their experiences of improved, friendlier services over the past six years. A driving force behind these improvements has been the South African Department of Health and the South African National AIDS Council (SANAC, which coordinates several government bodies) openly calling for services for sex workers and for decriminalization. A whole-of-government approach towards sex work that recognizes the rights and needs of this vulnerable group would make more sense and help end police practices that obstruct SANAC’s goals of ending the pandemic, for example detaining sex workers without access to antiretroviral drugs. [41]

Conclusion

In Africa, sex workers’ negative experiences with health services act as a powerful barrier to their accessing quality health care—by inhibiting effective treatment, prevention, and support for HIV and other health-related needs of sex workers, including their sexual and reproductive health, preventative care, and mental health [24, 42]. This chapter explored examples of how prejudices harboured by healthcare worker and non-clinical staff have a far-reaching negative impact on sex workers’ well-being and access to care. In contrast, positive interactions with healthcare providers and health services empower sex workers, affirm sex worker dignity and agency, and assist in cultivating healthy behaviour and improved health outcomes [33, 35, 43].

It is unfortunate that the clear evidence for the need to decriminalise sex work has not transformed the sorely outdated legal and policy landscape associated with the criminalisation of sex work, a landscape characteristic of most countries in Africa.

The political will, the necessary funding, and the urgency required to implement an effective response to sex work in Africa—and to do so at scale—are mostly absent. This remains the case, despite a large body of evidence and improved programmatic responses that support sex workers. Of particular concern, health programmes that focus narrowly on biomedical or behavioural HIV/STI prevention or treatment in relation to sex work remain myopic, as they focus only on sex workers’ sexual engagements, and do not address their broader health and social needs, their full humanity and personhood.

This can be overcome with comprehensive, rights-affirming health programmes designed in partnership with sex workers, combined with structural interventions that transform outdated legal frameworks and implement violence prevention strategies, psycho-social support services, and sex worker empowerment initiatives; and which galvanise peer-lead programmes that focus on strategic and practical sex worker needs in an African context. We are encouraged by the strides made towards these on a policy level in South Africa, with the passing of an official Sex Worker Plan. The crucial test, however, is how, and at what scale, the Plan has been implemented.

It is our hope that the voices of sex workers and sex worker rights advocates in Africa become stronger and are amplified on key platforms. When sex workers are supported to engage with policy makers, law enforcement agencies and health service providers in the African context, the urgent changes needed to affirm sex worker health and dignity and to make sex work safer will be prioritised.

Notes

- 1.

Pseudonym.

References

Chipfakacha V. Prevention of sexually transmitted diseases the Shurugwi sex-workers project. S Afr Med J. 1993;83(1):40–1.

Naidoo N. Report on the 1st African Sex Worker Conference: Building Solidarity and Strengthening Alliances, 3–5 Feb 2009, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Mgbako C, Smith LA. Sex work and human rights in Africa. Fordham Int Law J. 2011;33(4):1178–219.

NSWP. Global mapping of sex work laws 2018 [updated 31 December 2018; cited 2019 22 October]. Available from: https://www.nswp.org/sex-work-laws-map.

Amnesty International. Mapping anti-gay laws in Africa 2018 [31 May 2018]. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/lgbti-lgbt-gay-human-rights-law-africa-uganda-kenya-nigeria-cameroon.

Patrick M. HIV-specific legislation in sub-Saharan Africa: a comprehensive human rights analysis. Afr Hum Rights Law J. 2015;15(2):1996–2096.

Odendal L. HIV criminalisation on the rise, especially in sub-Saharan Africa 2016 [19 July 2016]. Available from: http://www.aidsmap.com/HIV-criminalisation-on-the-rise-especially-in-sub-Saharan-Africa/page/3072484/.

Secretariat: The Global Commission on HIV and the Law. The Global Commission on HIV and the Law - risks, rights and health. Geneva: UNDP, HIV/AIDS Group, Bureau for Development Policy; 2012.

Overs C, Hawkins K. Can rights stop the wrongs? Exploring the connections between framings of sex workers’ rights and sexual and reproductive health. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S6.

Dhana A, Luchters S, Moore L, Lafort Y, Roy A, Scorgie F, et al. Systematic review of facility-based sexual and reproductive health services for female sex workers in Africa. Glob Health. 2014;10:46.

Berer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: in search of decriminalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):13–27.

Pruss-Ustun A, Wolf J, Driscoll T, Degenhardt L, Neira M, Calleja JM. HIV due to female sex work: regional and global estimates. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63476.

Platt L, Grenfell P, Meiksin R, Elmes J, Sherman SG, Sanders T, et al. Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2018;15(12):e1002680.

Harcourt C, O’Connor J, Egger S, Fairley C, Wand H, Chen M, et al. The decriminalisation of prostitution is associated with better coverage of health promotion programs for sex workers. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34:482–6.

Shannon K, Crago AL, Baral SD, Bekker LG, Kerrigan D, Decker MR, et al. The global response and unmet actions for HIV and sex workers. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):698–710.

Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, Mwangi P, Rusakova M, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71.

Aroney E, Crofts P. How sex worker activism influenced the decriminalisation of sex work in NSW, Australia. Int J Crime Justice Soc Democr. 2019;8:50–67.

Smith M, Mac J. Revolting prostitutes: the fight for sex workers’ rights. London: Verso; 2018.

Mgbako CA. To live freely in this world: sex worker activism in Africa. New York: NYU Press; 2016.

UNAIDS. Communities at the Centre - Global AIDS Update 2019. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2019.

Scheibe A, Richter M, Vearey J. Sex work and South Africa’s health system: addressing the needs of the underserved. In: Padarath AKJ, Mackie E, Casciola J, editors. South African health review, vol. 19. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2016. p. 165–78.

Boyce P, Isaacs G. An exploratory study of the social contexts, practices and risks of men who sell sex in southern and eastern Africa. Nairobi, Kenya: African Sex Worker Alliance; 2011.

Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E, Richter M, Maseko S, Nare P, et al. “We are despised in the hospitals”: sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(4):450–65.

Binagwaho A, Agbonyitor M, Mwananawe A, Mugwaneza P, Irwin A, Karema C. Developing human rights-based strategies to improve health among female sex workers in Rwanda. Health Hum Rights. 2010;12(2):89–100.

Boyce P, Isaacs G. An exploratory study of the social contexts, practices and risks of men who sell sex in southern and eastern Africa. Oxford: Oxfam GB; 2011.

Boyce P, Isaacs G. Male sex work in southern and eastern Africa. In: Minichiello V, Scott J, editors. Male sex work and society. New York: Harrington Park Press, LLC; 2014.

Fobosi SC, Lalla-Edward ST, Ncube S, Buthelezi F, Matthew P, Kadyakapita A, et al. Access to and utilisation of healthcare services by sex workers at truck-stop clinics in South Africa: a case study. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(11):994–9.

Baleta A. Lives on the line: sex work in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2015;385(9962):e1–2.

Makhakhe NF, Lane T, McIntyre J, Struthers H. Sexual transactions between long distance truck drivers and female sex workers in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1346164.

Sellers DE, McGraw SA, McKinlay JB. Does the promotion and distribution of condoms increase teen sexual activity? Evidence from an HIV prevention program for Latino youth. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(12):1952–9.

Wang T, Lurie M, Govindasamy D, Mathews C. The effects of school-based Condom Availability Programs (CAPs) on condom acquisition, use and sexual behavior: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(1):308–20.

Global Fund. Baseline assessment – South Africa scaling up programs to reduce human rights related barriers to HIV and TB services, Geneva, Switzerland; 2018.

Nairne D. ‘Please help me cleanse my womb’: A hotel-based STD programme in a violent neighbourhood in Johannesburg. Res Sex Work. 1999;2:18–20.

Richter M. Sex work, reform initiatives and HIV/AIDS in inner-city Johannesburg. Afr J AIDS Res. 2008;7(3):323–33.

Stadler J, Delany S. The ‘healthy brothel’: the context of clinical services for sex workers in Hillbrow, South Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2006;8(5):451–64.

Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa (EHPSA). Just bad laws - the journey to the launch of South Africa’s National Sex Worker HIV Plan; 2018.

Richter M, Chakuvinga P. Being pimped out - how South Africa’s AIDS response fails sex workers. Agenda. 2012;26(2):65–79.

Richter M, Khosa T, Rasebitse K. Sex work and the ‘National Strategic Plan on HIV, STIs and TB 2017–2022’ – time to be brave! Spotlight [Internet]. 2017;. Available from: https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2017/03/14/sex-work-new-nsp/.

South African National AIDS Council. The South African National Sex Worker HIV Plan, 2016–2019. Pretoria; 2016.

South African Government Department of Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities. National strategic plan on gender-based violence & femicide: human dignity and healing, safety, freedom & equality in our lifetime. Republic of South Africa; 2020. https://www.justice.gov.za/vg/gbv/NSP-GBVF-FINAL-DOC-04-05.pdf. Accessed 5 Oct 2020.

Human Rights Watch. Submission by Human Rights Watch to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on South Africa 2018 [30 August 2018]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/08/30/submission-human-rights-watch-committee-economic-social-and-cultural-rights-south.

Pauw I, Brener L. ‘You are just whores: you can’t be raped’: barriers to safer sex practices among women street sex workers in Cape Town. Cult Health Sex. 2003;5:465–81.

Khonde N, Kols A. Integrating services within existing Ministry of Health institutions - the experience of Ghana. J Sex Work Res. 1999;2:16–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Richter, M., Buthelezi, K. (2021). Stigma, Denial of Health Services, and Other Human Rights Violations Faced by Sex Workers in Africa: “My Eyes Were Full of Tears Throughout Walking Towards the Clinic that I Was Referred to”. In: Goldenberg, S.M., Morgan Thomas, R., Forbes, A., Baral, S. (eds) Sex Work, Health, and Human Rights. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64171-9_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64171-9_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-64170-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-64171-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)