Abstract

Singapore introduced the Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century (TE21) in 2009 as a framework to propose a set of 21st century competencies that Singaporean teachers should be equipped with. The introduction of TE21 catalyzed the reform of existing programs and the implementation of new initiatives in initial teacher preparation programs and lifelong teacher professional development. This chapter first examines the local and international driving forces that led to the conceptualization of TE21 since Singapore’s independence. Then, the recommendations of TE21 are scrutinized along with the implementation of two new initiatives in the initial teacher preparation program. The findings are twofold. First, we find that Singapore has extensively performed a comparative review of global 21st century recommendations over four decades to customize an education system for their local context. Second, by synthesizing information sourced from interviews, government documents, and quantitative data, we find that the progress towards developing a cadre of 21st century teachers and producing holistic students in Singapore is largely successful. However, students are found to be at the receiving end of a generational cultural clash between them and their parents’ beliefs about the core of education.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

3.1 Introduction

The innovative and transformative Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century (TE21) was introduced in Singapore by the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NIE NTU, Singapore) in 2009. Frequently called revolutionary, this model is seen as the pinnacle of 21st century teacher education because it revamped the existing teacher education system to include 21st century values, skills, research, assessments, and professional development into a teacher’s trajectory. This framework has catalyzed the implementation of a variety of reforms in initial teacher preparation programs and lifelong teacher professional development initiatives that still exist today.

A recap of Singapore’s history will tell us that the country was initially struggling to stand on its feet after gaining independence from Malaysia in 1965. With no natural resources to fuel the economy, its leaders saw education as a sustainable investment towards its growth (Reimers & Chung, 2019). Since then, Singapore has gradually and continually paved a stable path towards developing a 21st century education system through four distinct phases over four decades: (1) survival-driven, (2) efficiency-driven, (3) ability-driven, and (4) values-driven, student-centric phases (Reimers & Chung, 2019). Coupled with political and economic stability, this nation now enjoys the luxury of continuity and high performance in its education system.

Despite Singapore’s success in building an exemplary 21st century education system over four decades, there is a gap in the literature about the external influences on the development of Singapore’s education system. For example, it remains unclear how Singapore’s developmental trajectory compares to international conversations about the future of education, such as the UNESCO reports Learning to Be headed by Edgar Faure in 1972 and Learning: The Treasure Within headed by Jacques Delors in 1996 (see Chap. 1 for more details). Even within the specific literature of Singapore’s 21st century teacher education system, they extensively discuss the conceptualization and the implementation of TE21 from the point of view of NIE NTU, Singapore (Saravanan & Ponnusamy, 2011; Tan, 2012; Tan, Liu, & Low, 2017), but relatively few of them have included external influences and responses from the most important stakeholder, the teachers.

Hence, there are two main objectives for this chapter. First, it aims to analyze the sequence of events and strategies employed by Singapore towards building a 21st century education system in tandem with international conversations surrounding the future of education over the four decades since Singapore’s independence. Second, this chapter will scrutinize the recommendations of TE21 and two specific reforms catalyzed by TE21 within the initial teacher education program while including individual opinions and experiences of teachers. We find that Singapore’s phases of education over four decades incorporated suggestions from international literature and evidence from local and global events to design a uniquely-Singaporean education system that leave teachers and students largely satisfied with the reforms brought about by TE21. However, despite Singapore’s meticulously-planned four decades and its institutional strength, we find that a cultural shift towards exemplifying 21st century competencies demands more than merely incorporating 21st century skills into the curriculum for students. A cultural reform is unfortunately challenging and appears to persist in systems regardless of their developmental stages (see Chap. 6 on Kenya for a cultural reform in a different context).

Information for this project was sourced from interviews with Prof. Tan Oon Seng, the immediate past Director of NIE Singapore and Prof. Low Ee-Ling, Dean of Teacher Education at NIE Singapore, one Principal, two Head of Departments, and three teachers from the Singaporean education system. Additional data was obtained from the NIE repository, the Ministry of Education (MOE) repository, the National Archive of Singapore, official Government of Singapore webpages, reports from the Organization of Economic Cooperation (OECD), peer-reviewed journal articles, and books written by the NIE members.

3.2 Marking the “Little Red Dot” by Its Phases of Education

Singapore is a densely populated land area of 719 square kilometers with a current estimated population of 5.7 million (World Development Indicators, 2020). Fondly referred to as the “Little Red Dot” by local politicians and international observers alike, this tiny and diverse island finds itself the subject of many conversations in the world, often for topping human development measures, including outcomes in education. Singapore’s commitment towards a good education system, including teacher preparation, began immediately after gaining independence from Malaysia in 1965.

In this post-independence era, dubbed the survival-driven phase, the main priority was economic survival using local talent. Teacher preparation and education opportunities were revamped while prioritizing basic literacy and mathematics skills in the curriculum (Reimers & Chung, 2019). The Teachers’ Training College launched its first set of degrees in education in 1971, a move which indirectly tagged prestige on the teaching profession while demonstrating a dedication towards building a strong and selective teacher body in the country (National Institute of Education Singapore [NIE], 2009). Not only that, the teacher education campus was prioritized for renovations to attract the best and the brightest into the field (Reimers & Chung, 2019). The country was satisfied with its average acquisition of literacy and mathematical skills from this survival-driven phase, but the generalized and basic education curriculum meant that disadvantaged students were left in the lurch and were often dropping out of schools. The next efficiency-driven phase was then introduced to provide high-quality alternative options for these students.

In the efficiency-driven phase from 1979 to 1996, differentiated streams were introduced to match students’ previous knowledge and ability to their academic trajectory. Thus, teachers with a variety of specializations beyond literacy and mathematical skills were needed, including expertise in technical and vocational skills and the arts. Unlike the survival-driven phase where quantity was prioritized, the quality of mass education in the efficiency-driven system was also deemed important. Accordingly, teacher preparation saw many specializations introduced within the broader field of education, including administrative, research, and leadership degree programs (NIE, 2009). Singapore’s system of streaming students based on their knowledge and ability in this efficiency-driven phase was an effective solution for the domestic economy; however, in mid-1990s, the nation began realizing that the education system was failing to bridge the gap between academic and non-academic social skills to remain a competitive force in the global economy (Reimers & Chung, 2019).

After the long and arduous efficiency-driven phase to improve mass education in Singapore, the country was prepared to move into an ability-driven phase where the main priority in education was the development of individual potential. The ability-driven phase, starting from 1997 to 2011, marked the wide and deliberate introduction of 21st century competencies in Singapore’s education system, including the initial teacher preparation program. While the goals of the ability-driven phase still resonate strongly within the education system, Singapore formally shifted to a values-driven, student-centric phase in 2011 that places character development at the core of the system (National Archives of Singapore, 2011). In this phase, teachers have the added responsibilities of instilling values in each student and reaching out to the community with the aim of producing a holistic ecology for learning (Reimers & Chung, 2019). The ability-driven and values-driven, student-centric phases underscore TE21’s recommendations and will be elaborated in great detail in the subsequent sections.

These four, well-planned phases that build from previous phases’ successes and shortcomings while taking present domestic and global challenges into account demonstrate the gradual growth of Singapore’s education system to be among the best in the world. The country and its different leaders over the course of four decades constantly prioritized education because building human capacity was the only way to propel the country’s economy forward. Not only did the country prioritize educational outcomes for students, they also realized that teachers are the driving force behind student outcomes, and this theory of change will be discussed in Sects. 3.3 and 3.4.

3.3 Local and International Context

In order to comprehend how and when Singapore started with its teacher education reform, we first need to understand the local and global landscapes that shaped Singapore’s agenda. This section will explore international conversations surrounding 21st century skills and teacher education, and conduct a comparative analysis between these conversations and Singapore’s phases of education.

3.3.1 21st Century Skills

Approaching the turn of the millennium in the late 1990s, the world witnessed an unprecedented rapid increase in technological changes and innovation. Due to the quickly-evolving technological landscape, Bransford (2007) notes that innovation cycles start and end within a short frame, and that education systems are often unable to adapt to meet the demands of a field. Hence, the training provided at educational institutions may be nugatory by the time students enter the workforce. These changes were foreseen by some visionaries even in the 1970s and they gradually laid the foundations for conversations surrounding 21st century teaching and learning to take place. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was instrumental in leading the discussion surrounding the future of education. The organization published two foundational reports on adaptive and lifelong learning, Learning to Be headed by Edgar Faure in 1972 and Learning: The Treasure Within headed by Jacques Delors in 1996 (see Chap. 1 for more details). While there is a lack of evidence to support Singapore’s references of these specific UNESCO reports to inform its curriculum and teacher preparation programs, Prof. Tan Oon Seng, the immediate past Director of NIE Singapore and Prof. Low Ee-Ling, Dean of Teacher Education at NIE Singapore recognize that “the publications from world bodies and think tanks have always been part of [their] literature review and global environment scan, whether they be from international academic colleagues or global organizations, such as UNESCO, OECD” (Low & Tan, 2020). The comparison of the timelines of these two formative UNESCO reports to that of the Singaporean education system is illuminating because it demonstrates how quickly Singapore, which only gained independence in 1965 with no natural resources to fuel the economy, was able to mobilize its talents to be among the best within a short time. In 1972, Singapore was still in its post-independence survival-driven phase when The Faure Report argued for progressive lifelong education in the world. Remarkably, in 1996, Singapore was wrapping up with its efficiency-driven phase and preparing to move on to an ability-driven phase that will respond to economic, social, and technological change in the country and globally—all of which align with pillars of education found in The Delors Report.

By the end of the millennium, governments, education scholars, and organizations were forced to confront the nimbleness of the global innovative space and to find a common ground for the future of education. Singapore was no exception—the increasing income gap approaching the 1997 Asian financial crisis meant that wealthier families could afford private tuition to assist their children achieve excellent grades while the rest of the students were struggling to even pass (Lee & Low, 2014). A country that largely relies on its human capital cannot afford such a disparity in its educational outcomes, especially when the world is rapidly innovating. Shortly before the Asian financial crisis beset Southeast Asians nations in July 1997, Singapore’s Prime Minister at the time, Goh Chok Tong, announced the government’s new vision for the Ministry of Education (MOE) “Thinking Schools, Learning Nation” (TSLN) in June 1997. This vision, which launched two decades of major structural overhaul in four broad areas—namely, infrastructure of the education system, curricula and assessment, training and development, and school environments—was initiated to prepare citizens who are committed and capable of meeting future challenges using 21st century skills (Ministry of Education, 2019).

At the start of the 21st century, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has also led two initiatives for its member nations to define and assess 21st century competencies: The Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo) project and the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) for mathematical, scientific, and reading literacies. DeSeCo and PISA go hand-in-hand because the former, which was published in 2003, provides a framework for the latter that also began in 2003. DeSeCo’s framework is grounded in three broad competencies for individuals, which are abilities to use tools interactively, to interact in heterogeneous groups, and to act autonomously (Rychen & Salganik, 2003). No representatives from Singapore were involved in the conception of DeSeCo or PISA, and yet, within the last two decades, Singapore, an OECD member, has been consistently ranked among the top five in the 70-nation PISA test. What these numbers mean relative to other participating countries is astounding: “90 percent of Singaporean students scored above the international average in mathematics and science, and Singapore’s fifteen-year-olds outperformed those of every country in reading, mathematics, and science” (National Center on Education and The Economy: Empower Educators, 2017, p. 1). These consistent results speak volumes about Singapore’s ability as a nation to reach its educational potential as defined by the DeSeCo Project and PISA through its successful implementation of 21st century competencies in its education system.

Within the two decades of the 21st century, several scholars and organizations have proposed their definitions of 21st century skills. While many reports to date that propose 21st century skills have been the product of evaluations based on the economic demands and skill gaps of the global landscape, an influential report that incorporated scientific evidence from the social sciences is the National Research Council report (2012), Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st century, commonly known as the Hilton and Pellegrino report. The authors not only included proposals for the development of human capital as supported by psychological research, but they also posed evidence-based consequences for individuals in the short- and long-run based on the development of their competencies. By synthesizing scientific research in the field of human development, Hilton and Pellegrino propose a 21st century framework that covers cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal competencies in detail. Singapore, in actuality, had developed a 21st Century Competencies (21CC) framework for its national curriculum in 2010, shortly before the Hilton and Pellegrino report was released. Singapore’s 21CC framework has a set of core values that are self-oriented, and broader sets of values that signify socio-emotional and global competencies. While Singapore developed its framework using locally-generated evidence-based educational review and research, the contrasting of Singapore’s 21CC framework to the Hilton and Pellegrino report reveals striking similarities. In a very recent comparison done between the two frameworks, Reimers and Chung (2019) finds that Singapore’s competencies fit well into the three broad categories proposed by Hilton and Pellegrino; hence, it demonstrates that Singapore’s 21CC framework is grounded in a universal psychological framework for the 21st century despite being based on locally-sourced evidence.

3.3.2 21st Century Teacher Education

Teacher education programs have been around since the nineteenth century, but how and why teacher education impacts students is not self-evident to many; therefore, teacher education is often the subject of criticism for being ineffective despite being a prerequisite to teach. In fact, even in developed education systems, changes to the teacher education system happen much later or less rigorously. To dispel the myth that anyone can be a teacher and that teacher education systems are unnecessary and ineffective, Darling-Hammond (2000) published an article discussing evidence supporting the claim that teacher education results in teacher effectiveness, which in turn improves student outcomes. This article—aptly produced at the turn of the millennium—found that “teaching for problem solving, invention, and application of knowledge requires teachers with deep and flexible knowledge of subject matter who understand how to represent ideas in powerful ways and organize a productive learning process for students who start with different levels and kinds of prior knowledge, assess how and what students are learning, and adapt instruction to different learning approaches” (Darling-Hammond, 2000, p. 166–7). The idea that teachers require “deep and flexible knowledge” from Darling-Hammond is central to teaching and learning in the 21st century if students are expected to possess the 21st century skills discussed in the previous section. A similar logic is found to be the impetus for Singapore’s teacher education reform. TE21 is the product of a prevalent notion when TSLN was introduced, which is the realization that ‘21st century learners call for 21st century teachers’ (NIE, 2009).

Over the following years, several articles and books were published proposing the incorporation of 21st century competencies into teacher education programs, and these writings collectively carved the definition of 21st century teacher education. Darling-Hammond and Bransford (2007) published a formative report commissioned by the National Academy for Education titled Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers Should Learn and Be Able To Do, which provides common elements that should be part of a teacher education curriculum. The authors propose a framework that recommends new teachers in the 21st century to have a basic understanding of learning sciences, language acquisition, diversity in learning, classroom management, innovative assessments, the use of technology in classrooms—all of these in addition to deep and flexible subject matter knowledge (Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2007). With Darling-Hammond and Bransford (2007) providing a framework for teacher education curriculum, Korthagen, Loughran and Russell (2006) attempted to identify common fundamental principles that should be inculcated in teacher education programs to produce teachers who are responsive in a dynamic manner for the 21st century. The authors provide seven simple yet thought-provoking principles about learning that shifts the mindset of teachers to continuously strive for their students’ successes while embodying 21st century skills themselves. The principles are: learning about teaching involves continuously conflicting and competing demands, requires a view of knowledge as a subject to be created rather than as a created subject, requires a shift in focus from the curriculum to the learner, is enhanced through student-teacher research, requires an emphasis on those learning to teach working closely with their peers, requires meaningful relationship between schools, universities and student teachers, and is enhanced when the teaching and learning approaches advocated in the program are modelled by the teacher educators in their own practice (Korthagen et al., 2006). Parallels in the types of innovative student assessment methods can be drawn between Darling-Hammond and Bransford (2007), (Korthagen et al., 2006) and the teacher education reform in Singapore, specifically on how to teach the differences between formative and summative assessments that are viable options for the 21st century. A combination of the different types of assessments bode well with the goal of building students’ unique characters in the values-driven, student-centric phase because students will be forced to reflect on their progress and the final outcome simultaneously. In an education system that has singularly focused on final examinations as the only method of assessment, innovative formative components, such as wholesome learner’s portfolios, can shift the culture in schools and instil new values.

Further adding to the repertoire of teacher education models is Hoban (2007)‘s book, The Missing Links in Teacher Education Design: Developing a Multi-linked Conceptual Framework. This book focuses on the common gaps across teacher education programs, specifically in university curriculum, the theory-practice links between schools and university, the diversity in teacher education programs, and the personal narratives of teachers and teacher educators that shape their identities. The content of each chapter zooms into a particular teacher education program and the link that they were trying to make between stakeholders in their context. The authors for each case also briefly discuss the challenges they face, which include issues with securing buy-ins from various organizations and teaching bodies to realize the program. In Singapore’s teacher education reform, it is evident that the challenges within these different contexts were thoroughly studied as a unique tripartite relationship was proposed to bring the equal weight of the MOE, the NIE and schools together in order to minimize friction between different entities while strengthening the theory-practice link within the local context (NIE, 2009).

While the surveyed literature was written about and for the Western context, Prof. Tan and Prof. Low explained how useful the key findings and recommendations were when the NIE was adapting and contextualizing them for Singapore with an Asian perspective in mind:

We acknowledge that a large part of research literature is still today primarily Western in orientation. But we have never shied from looking at best international ideas and asking how they can be applied to our local context. Singapore is unique from many other countries, especially Western ones, and so it is by necessity that we need to contextualize any of the international best practices and literature to our circumstances. When we contextualize, we do not change our Asian philosophy. For example, the goal of education in the Western context is freedom through individual rights. In the Asian context, the goal of education is freedom through group, family and societal cohesiveness. We are more inclined towards community harmony and the societal good as a whole. We keep to this core value of the collective welfare of all (Low & Tan, 2020).

3.4 Goals in 21st Century Teacher Education and the Theory of Action

After the announcement of TSLN in 1997, a number of initiatives were systematically implemented to include 21st century skills into the national curriculum; but the realization that ‘21st century learners call for 21st century teachers’ (NIE, 2009) called for the MOE in collaboration with the NIE to perform an extensive review of the initial teacher preparation program, known as the Programme Review and Enhancement 2008–2009 (PRE).

3.4.1 Program Review and Enhancement 2008–2009 (PRE)

The PRE committee consisted of NIE professors and researchers led by the Director of the NIE at the time, Dr. Lee Sing Kong (NIE, 2009). The underpinning philosophy that guided the PRE committee was the purpose of education as outlined by the MOE: “to nurture the whole child –morally, intellectually, physically, socially, and aesthetically” (NIE, 2009, p. 28). The PRE committee’s theory of change assumes that students’ development of 21st century skills emerges as a result of competent 21st century educators. Therefore, the PRE committee first charted the intended student outcomes in a 21CC instructional setting. The outcomes included (1) learning and innovation skills, (2) knowledge, information, media and technology literacy skills, (3) life skills, and (4) citizenship skills (NIE, 2009). To match these student skillsets to teacher competencies, the PRE committee designated three areas within 21CC that teachers need to develop: (1) expertise at the intersection of information, media, and multicultural literacy, (2) knowledge in supporting learning communities that allow students to integrate 21CC into classroom practice and real world contexts, and (3) effective instruction of 21CC that support innovative pedagogies and high order thinking skills. A tangential but laudable outcome of the PRE is the beginning of systematic incorporation of evidence-based educational practices that were tested and proven in Singapore into any changes of their teacher preparation programs. For effectiveness of educational policies, Singapore’s theory of action included an Enhanced Partnership Model that places equal importance on three primary bodies of education, namely MOE, NIE, and schools (NIE, 2009). Based on the understanding of existing and emerging trends using rigorous data collection and analysis through the PRE process, the Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century (TE21) framework was introduced in 2009.

3.4.2 The Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century (TE21)

The key takeaways from the PRE process were mapped into six recommendations by the PRE committee that were deemed crucial to the holistic development of teachers, which in turn serves as an investment towards equipping young Singaporeans with 21st century competencies. To support the implementation of these recommendations, the budget for education increased by 11% in 2010; hence, bringing the total amount allocated for education from 8.70 billion Singaporean dollars (S$) to S$9.66 billion for the year following the introduction of TE21 (Tan et al., 2017; Singapore Budget, 2010, 2011).

3.4.2.1 Recommendation 1

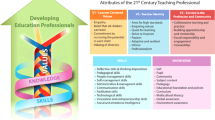

The New V3SK Model aligns well with Singapore’s newest phase in education starting in 2011, which is the values-driven, student-centric phase. Initially introduced as the ASK Model (Attitudes, Skills and Knowledge) then the VSK Model (Values, Skills and Knowledge), the New V3SK Model prioritizes the child, individual identity, and the community within important values that will “permeate the programmes and curricula” (NIE, 2009, p. 45). The derivation of this new model demonstrates the fluidity of the Singaporean education system as it has undergone three variations in one decade to meet the rapidly changing needs of the global landscape. The attributes of a 21st century teaching professional under the New V3SK Model are formalized as having the Values of learner-centeredness, teacher identity, and service to the profession and community, the Skills required by an educator, and in-depth subject-matter Knowledge. Even though the focus of this model is to understand every child’s individual learning profile, teachers need to have high standards to maximize the child’s potential and a drive to learn to adapt accordingly to each individual learner. At the core of this symbiotic teacher-child relationship is believing that every child can learn and contribute as an outstanding member of society.

3.4.2.2 Recommendation 2

The PRE committee recommends that the NIE’s Initial Teacher Preparation (ITP) and Postgraduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) programs incorporate Singaporean context-specific 21st century teacher competencies in their graduation criteria. The list of guidelines for the criteria is known as the Graduand Teacher Competencies (GTCs), and it is reflected in the GTC Framework (GTCF) for trainee teachers. While there is no one-to-one mapping between the New V3SK Model and GTCs, the values, skills, and knowledge inform the three performance dimensions that support 21st century instruction in classrooms. The dimensions identified by the PRE committee are professional practice, leadership and management, and personal effectiveness (NIE, 2009). A crucial point to note about the GTCs is that these competencies should be demonstrated at the point of graduation from ITP and PGDE programs, but some core competencies within each dimension cannot be realized until after the teacher is in the field. For example, the GTCF states that a teacher should take the initiative to improve their professional development throughout their teaching tenure, but the NIE is unable to measure this competency at the point of graduation. Therefore, the Enhanced Partnership Model will ensure continued mentoring after the teacher has graduated from the training programs. This example of post-graduation training to improve teacher skills aligns with the development of a teacher identity as outlined in the New V3SK Model while enforcing the receptiveness for adaptability in the teaching profession.

3.4.2.3 Recommendation 3

The PRE committee recommends bridging the gap between theory and practice within teacher education by strengthening the theory-practice nexus. This process is not at all simple as the gap between theory, policy, and practice is evident in many fields, especially in the social sciences and humanities. The NIE has proposed four approaches that encompass theory and practice within evidence-based teacher education, namely reflection, pedagogical tools that bring the classroom into the university, experiential learning, and school-based enquiry or research. The basis of this recommendation is that teachers utilize research in pedagogy to inform their classroom practices and use classrooms as a research ground to test teaching strategies that can be extrapolated to the larger education sector in the Singaporean context. The Enhanced Partnership Model that brings the equal weight of MOE, NIE and schools together is pertinent for the success of this recommendation. Ideally, the NIE would provide the theoretical expertise via teacher education programs, the MOE act as policymakers, and schools would provide the research ground during their teacher preparation programs to develop evidence-based teaching practices.

3.4.2.4 Recommendation 4

The PRE committee recommends program refinement and an extended pedagogical repertoire as TE21’s fourth goal. Following on from TSLN, academic curriculum and co-curricular activities for students have been revamped to account for the incorporation of 21CC. Similarly, teachers need a framework that will inculcate 21CC instruction in teacher trainees through the NIE ITP and PGDE curricula. A powerful and observable culture in Singapore, for example, is the obsession with grades and academic excellence bar none, as suggested by Reimers and Chung (2019). An innovative and collaborative change within an academic system that has solely relied on grades at every level of instruction is no easy task. Therefore, teachers need to be equipped to propel a cultural shift to change the mindset of parents and students despite being the result of a previous examination-oriented system. The PRE committee proposes establishing a strategy and framework for 21st century teaching and learning that will uphold the following principles within the Singaporean education system: (1) a pedagogy curriculum must be discipline-appropriate as the basis of multi-disciplinary learning; and (2) these pedagogies must be learner-centered (NIE, 2009). Some examples of teaching practices that move further away from examinations include facilitating blended learning, role playing, experiential learning, and problem-based learning within classrooms.

3.4.2.5 Recommendation 5

Establishing an assessment framework for 21st century teaching and learning is necessary to measure the success of initiatives in Singapore. Assessments typically manifest as examinations in Singapore. Nonetheless, with the changes to include 21st century competencies in the education system, assessment methods need to evolve to meet the needs of the 21CC curriculum for students. The PRE committee recommends an assessment framework that “will enable [Singapore] to produce teachers who have high assessment literacy levels and able to adopt the best practices to effectively evaluate student outcomes” (NIE, 2009, p. 95). The NIE wants to move away from examination grades as the only means of assessment and they believe that the training starts at the ITP and PGDE programs. In fact, a wholesome portfolio assessment that covers multiple perspectives and a range of platforms is recommended for teacher training assessment too. The hope is that teachers will learn how individual learners’ portfolio assessment works on a multifaceted dimension to productively benefit a student’s holistic development instead of merely developing an excellent test-taker.

3.4.2.6 Recommendation 6

The PRE committee recommends establishing enhanced pathways for professional development. Given that fluidity and adaptability to challenges are part of the TSLN vision, this recommendation proposes the provision of alternative accelerated pathways for professional upgrading that will instill a lifelong learning experience for teachers. A feature that Singapore has observed in other high-performing countries such as Finland is the high baseline academic qualification for teachers (NIE, 2009). A lifelong professional development opportunity with high standards not only attracts the best to the teaching profession, but it also goes hand-in-hand with almost all of the other recommendations, including bridging the theory-practice gap by continuously informing themselves of the latest developments. The PRE committee recommends altering the bachelors program in teaching to include an accelerated masters program for qualified teacher trainees so that they benefit from additional evidence-based training through school attachments and research experience.

3.5 Implementation of TE21 Recommendations in the Teacher Preparation Program

A slew of programs and initiatives were introduced by the NIE, the MOE, schools after the introduction of TE21. As this chapter focuses on the initial teacher preparation reform in Singapore, this section will sample the implementation of two selected initiatives that encompass the first five recommendations from Sect. 3.4.

3.5.1 Learning e-Portfolio

As part of the revamp of the ITP and PGDE programs, the NIE introduced a new course called the Professional Practice and Inquiry (PPI) course to allow pre-service teachers to formulate their own teaching philosophies. The PPI course was first introduced to junior college trainee teachers in July 2010 before being introduced to all trainee teachers by July 2012 (Tan et al., 2017). This course was introduced with the goal of tying together Recommendations 1, 2, and 3; specifically, the PPI intends to provide a space for pre-service teachers to identify and reflect on the values of teaching and learning that will scaffold their future classroom experiences while meeting the set of competencies established by the GTCs. A huge motivation for this effort was also to ensure continuity for teachers to aggregate their learning and modify their philosophical models as they see fit throughout their pre-service training and careers. To meet all these goals, the NIE introduced the e-Portfolio, which is an electronic platform for teachers through the PPI course to reflect and track their knowledge while maintaining a collection of artefacts that align with the requirements of the GTCs (Tan et al., 2017).

The e-Portfolio is not merely a diary of theoretical philosophy developed by trainee teachers; it is in fact used simultaneously as pre-service teachers undergo their practicum experience. Trainee teachers have multiple opportunities to revise their teaching identity and philosophy using locally-generated, evidence-based results. The interweaving of theory and practice through the e-Portfolio is especially valuable in the final practicum experience as teachers are often placed in schools that will be their post-training permanent working environment. Just as trainee teachers are taught to develop these portfolios, they are instructed to guide their future students to develop similar learning portfolios for formative assessments. A current biology teacher in a junior college who underwent teacher training via the PGDE program in 2013–2014 reflected on her e-Portfolio experience and was thrilled that the methods introduced at the NIE were viable options for her future students in classrooms too. Linking her e-Portfolio experience to her practicum, she said that the feedback loop between theory in lectures and application during her practicum gave her plenty of opportunities to learn about values that were integral to herself and to craft her personalized e-Portfolio (Biology Teacher 1, 2019).

3.5.2 Experiential Learning

Recommendation 4 and 5 of TE21 highlight the need to develop learner-centered pedagogy curriculums with the potential for holistic assessments. One such initiative is the mandatory requirement of experiential learning in a variety of subjects in secondary schools and junior colleges. Examining the secondary school and junior college geography curricula specifically, the MOE previously recommended fieldwork whenever possible, but it was not mandatory. These excursions and field trips were not necessarily reflective or illuminating for the students; in fact, Chew (2008) claims that assessments for such excursions typically involve regurgitation of information provided by teachers and tour facilitators (Tan et al., 2017).

In the spirit of providing teacher trainees with similar curriculum and assessment methods as expected for their future students, the NIE introduced experiential learning and assessment in the PGDE program in 2010 for geography pre-service teachers. These trainee teachers were given access to leading experts in fieldwork and extensive training on how to critically conduct fieldwork. At the end of the program, they were expected to create an experiential learning package using fieldwork for secondary schools or junior colleges. Tan, Liu, and Low (2017) found that these trainee teachers had a renewed appreciation for critical and analytic fieldwork which was drastically different from their personal experiences with field trips.

One secondary school geography teacher who participated in the PGDE program from 2016–2017 was so excited about the experiential learning reform that he began designing his experiential learning package during his undergraduate degree. He never had the luxury of travelling much when he was younger; when he got a teaching scholarship to get his undergraduate degree in California, he knew he had the make the best of the opportunity not just for himself, but for his career as a geography teacher too. He planned trips to national parks and searched for study abroad opportunities to see the world and think about potential ways he could use his travel experiences as inspiration for his future students. Using the activities from his college travel experiences as a guide, he planned a fieldwork trip to an island for his students to investigate the physical geography using hand-ons activities instead of passively observing on tours (Geography Teacher, 2019).

3.6 Success and Persistent Challenges

Given that a variety of programs and modules were introduced following from the TE21 framework, a thorough analysis of the combined effectiveness of all the programs is an impossible task. However, with quantitative data from global organizations and personal anecdotes from the teachers interviewed, we can infer the success and persistent challenges of these programs.

3.6.1 Teaching, Learning, and Research

The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) administered by the OECD is the largest international survey held every 5 years about educators’ working conditions, learning environments, and teaching styles. Singapore unfortunately did not participate in the inaugural survey in 2008; hence, we do not have a baseline condition before TE21 was introduced in 2009. However, Singapore participated in the 2013 and 2018 surveys, and we can compare the results in those years to each other and to the OECD averages. Singapore stands out among other OECD countries in most of the parameters measured. One measure that is indicative of 21st century teaching style is the percentage of time teachers spend actively teaching, which implies more time for students to self-direct during a lesson. Singapore was at 71% in 2013 and 74% in 2018, when the OECD averages float around 80%. (OECD, 2014, 2019a). This measure provides evidence for the many opportunities of autonomous learning for students that not only allow them to reflect on their individual learning styles, but also inculcate curiosity and creativity that are central features of a 21st century education.

Changes to the teacher education program requires time to permeate the education system and produce visible results in student outcomes. The NIE has made recent efforts to develop 21st century skills assessment methods for the Singaporean context. In 2015, the NIE launched a new journal, Learning: Research and Practice to encourage and support “distinct and progressive research that responds to the problems of current educational practices and traditional views of learning” (“Learning: Research and Practice”). This journal tracks the research done in the Singaporean context that attempts to investigate 21st century pedagogical and assessment methods. While Singapore has not conducted large-scale studies to measure the effectiveness of its 21CC instruction, trial studies in selected schools and student populations have experimented with different methods of teaching and assessing 21CC skills in classrooms. Tan, Caleon, Ng, Poon, and Koh (2018), for example, have shed some light on how Singaporean students respond to collective creativity and collaborative problem solving in manipulated settings. Koh, Hong, and Tan (2018) has experimented with technology to assess self-awareness and teamwork-awareness in a pilot population. While none of these studies have conclusive evidence that can be extrapolated to all students in Singapore, they certainly pave the path towards larger experiments involving 21st century skills in the near future.

3.6.2 Institutional Strength

As evident from the comparison of Singapore’s development in education to the two UNESCO reports, Learning To Be and Learning: The Treasure Within, Singapore caught up and overtook the rest of the world at an unprecedented rate. Reimers and Chung (2019) allude to two reasons for Singapore’s rapid success in developing its education system: (1) the small size of Singapore and its centralized education system allow for quick and coherent nationwide implementations of policies and initiatives; and (2) the education system has been dynamic and adaptive to changes in the local and global landscape and accordingly aligns its goals to foreseeable challenges. While Singapore’s physical size certainly promotes efficient implementation, we cannot discount the decades of calculated design of the entire education system. Singapore’s size merely bolsters the strength of the educational programs and policies, including the implementations of the recommendations from TE21.

A Principal at a low-performing secondary school, who has been in the teaching force for two decades, observed that the more recent pre-service teachers who joined his school for their practicum bring in new ideas to engage students in different types of activities that they believe will boost students’ interests in academics. One example that remains in his memory to this day is the creative idea proposed by a new chemistry teacher to use physical exercise as the medium to introduce chemical reactions to his students. The teacher’s logic was simple: most of the students in his class were athletes and the best way for them to approach chemistry with less fear was to combine it with their activities of interest. The Principal was not well-versed with TE21 before our interview, but he was quick to note the connection between the introduction of TE21 and the point at which he started observing changes in pre-service teachers’ enthusiasm for innovation, especially in thinking about addressing equity at a low-performing school. Witnessing the intended outcomes of reforms that follow from TE21 at schools in a relatively short time suggests that Singapore’s education system is highly coordinated to disseminate and affect changes at multiple levels in a rapid manner (Principal, 2020).

3.6.3 Autonomy at Higher Levels

The changes brought about by TE21 heavily focus on improving pre-service training by the NIE and lifelong professional development by the MOE. These facets of development do not directly address how teachers in leadership positions, such as Head of Department or Principal, can assist the teachers under their purview to improve their 21st century skills. Due to the lack of specific instructions to teachers in leadership positions, there is a large variation in the types of activities that teachers can participate in. One teacher, who is also the Head of the Mathematics Department at his junior college, noted the similar profiles of pre-service teachers entering the school for their practicum who get vastly different opportunities within the same school depending on their departments. Every department gets the same set of broad guidelines for pre-service teachers’ 3-week practicum that include the basics such as classroom observations and mentorship meetings, but each Head of the Department (HOD) has the freedom to plan how to execute them. The Mathematics HOD at the junior college observed that HODs, for example, interpret mentorship meetings differently. He typically performs 1-on-1 check-in sessions with pre-service teachers under his purview, but another HOD could count departmental meetings as mentorship meetings (Mathematics HOD, 2020). Another teacher, who is the Head of the Economics Department in her school, confirms that professional development sessions are subjective and that they vary drastically by department. She says that HODs have the autonomy to conduct the in-house departmental professional development sessions as they see fit; therefore, even teachers within the same school can have very different in-house professional development experiences (Economics HOD, 2019).

3.6.4 Resistance Towards a Cultural Reform and Its Effects on Students

Reimers and Chung (2019) have identified challenges within the education system that can be addressed with increased efforts to hear the voice of a key stakeholder, the parents, and clearer communication on expected student outcomes. A biology teacher at a high-performing junior college has a difficult time justifying her teaching methods to some parents. When she tells parents about the innovative projects that their children were involved in, most parents question the need for such activities when their children’s A-Level results is the sole determinant for university entrance (Biology Teacher 2, 2019). While the tertiary education admittance system is an obstacle towards implementing 21st century teaching methods, the resistance by some stakeholders reflects the deeply ingrained belief that test-taking is the most important skill to be taught and learned in schools.

The most recent PISA assessment in 2018 included school climate and socioemotional development, in which Singapore had conflicting findings that reflect the state of confusion of students regarding their expected outcomes. 68% of students in Singapore were reported to cooperate with their classmates when the OECD average is at 62%, yet 76% were reported to compete with their classmates when the OECD average is much lower at 50% (OECD, 2019b). Students in Singapore are bullied at a higher rate at 26% compared to the OECD average at 23%, yet 94% of students thought that it is good to help those who are unable to defend themselves when the OECD average is at 88% (OECD, 2019b). These results suggest a tension between the push from the education system towards embodying 21st century skills and the advise from parents and some teachers to compete with each other for academic excellence. From the outset, the findings appear to reflect the clash of ideologies and beliefs between two generations that have been and are a part of vastly different education cultures.

3.7 Conclusion

There are two main takeaways from this chapter. First, by examining the literature around the time of TE21’s introduction, it is evident that Singapore extracted concepts from suggested 21st century teacher education designs and adapted them for a Singaporean context, which align with the psychological framework for reform. They not only incorporated these suggestions, but they also anticipated challenges based on other existing models and designed solutions that will make the revamp process as seamless as possible. Darling-Hammond (2006) calls for resisting the pressure against watering down teacher preparation programs simply because it is impossible to work around certain challenges, and Singapore has taken that very seriously to design a well-planned 21st century teacher education program. Second, Singapore’s implementation of TE21 has many lessons to offer to other countries. It has adhered to the ingredients of a successful institutional reform, including the involvement and communication with the majority of key stakeholders, incorporation of evidence-based teaching practices, and enforcement of a nimble yet well-fortified system—there seems to be almost no anticipation of failure. Despite being close to perfection, it is important to also investigate the responses that the framework has generated from key stakeholders. While there are no major failures at this stage of the reform, unaddressed persistent challenges, such as the resistance towards a cultural shift in the society as a whole, will only be detrimental to the education system in the long run.

References

Biology Teacher 1, personal communication, November 27, 2019.

Biology Teacher 2, personal communication, December 6, 2019.

Bransford, J. (2007). Preparing people for rapidly changing environments. Journal of Engineering Education, 96(1), 1–3.

Chew, E. (2008). Views, values and perceptions in geographical fieldwork in Singapore schools. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 17(4), 307–329.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). How teacher education matters. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 166–173.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300–314.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (Eds.). (2007). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. Paris: UNESCO.

Economics HOD, personal communication, December 2, 2019.

Faure, E. (1972). Learning to be: The world of education today and tomorrow. Paris: UNESCO.

Geography Teacher, personal communication, November 14, 2019.

Hoban, G. (Ed.). (2007). The missing links in teacher education design: Developing a multi-linked conceptual framework (Vol. 1). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany/Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Koh, E., Hong, H., & Tan, J. P.-L. (2018). Formatively assessing teamwork in technology enabled twenty-first century classrooms: Exploratory findings of a teamwork awareness programme in Singapore. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 38(1), 129–144.

Korthagen, F., Loughran, J., & Russell, T. (2006). Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(8), 1020–1041.

Lee, S. K., & Low, E. L. (2014). Conceptualising teacher preparation for educational innovation: Singapore’s approach. In Educational policy innovations (pp. 49–70). Singapore: Springer.

Low, E. L., & Tan O. S. (2020). email correspondence, February 11, 2020.

Mathematics HOD, personal communication, January 13, 2020.

Ministry of Education. (2019, August 22). Retrieved October 17, 2019, from http://www.moe.gov.sg/about

National Archives of Singapore. (2011, September 22). Retrieved February 1, 2012, from https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/20110929001/wps_opening_address_(media)(checked).pdf

National Center on Education and The Economy: Empower Educators. (2017, February). Retrieved October 17, 2019, from http://ncee.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/SingaporeCountryBrief.pdf

National Institute of Education Singapore. (2009). A teacher education model for the 21st century. Retrieved from https://www.nie.edu.sg/docs/default-source/te21_docs/te21-online-version%2D%2D-updated.pdf?sfvrsn=2

National Institute of Education (NIE), Singapore. (n.d.). Learning: Research and practice. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from https://www.nie.edu.sg/research/publication/learning-research-and-practice

National Research Council. (2013). Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

OECD. (2014). TALIS 2013 results: An international perspective on teaching and learning. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019a). TALIS 2018 results (Volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019b). PISA 2018 results (Volume I, II, & III): Combined executive summary. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Principal, personal communication, January 17, 2020.

Reimers, F. M., & Chung, C. K. (Eds.). (2019). Teaching and learning for the twenty-first century: Educational goals, policies, and curricula from six nations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Rychen, D. S., & Salganik, L. H. (2003). Key competencies for a successful life and well-functioning society. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe Publishing.

Saravanan, G., & Ponnusamy, L. (2011). Teacher education in Singapore: Charting new directions. Journal of Research, Policy & Practice of Teachers & Teacher Education (JRPPTTE), 1(1), 16–29.

Singapore Budget. (2010). Expenditure overview 2009: Ministry of education. Retrieved from http://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget_2009/2009/expenditure_overview/moe.html

Singapore Budget. (2011). Expenditure overview 2010: Ministry of education. Retrieved from http://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget_2010/expenditure_overview/moe.html

Tan, J. P. L., Caleon, I., Ng, H. L., Poon, C. L., & Koh, E. (2018). Collective creativity competencies and collaborative problem-solving outcomes: Insights from the dialogic interactions of Singapore student teams. In Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 95–118). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Tan, O. S. (2012). Fourth way in action: Teacher education in Singapore. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 11(1), 35–41.

Tan, O. S., Liu, W. C., & Low, E. L. (Eds.). (2017). Teacher education in the 21st century: Singapore’s evolution and innovation. Springer.

World Development Indicators. (2020). Retrieved February 1, 2020, from https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&country=SGP

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rajandiran, D. (2021). Singapore’s Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century (TE21). In: Reimers, F.M. (eds) Implementing Deeper Learning and 21st Century Education Reforms. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57039-2_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57039-2_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-57038-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-57039-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)