Abstract

Improving outcomes through patient-centered care has emerged as an important focus of study in the clinical and research worlds over the past decade. While the principles of patient-centered care and community-centered care are found in philosophical writings in ancient times, only recently have physicians and the overall healthcare community begun to accept that the health and well-being of patients depends upon collaborative and integrated efforts between healthcare professionals, patients, and their communities. The aim of this chapter is to provide perspective and practical guidance on the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and extramural Dissemination and Implementation funding for telemedicine and telehealth-related research. Hopefully, this data analysis provides new ideas about how to be successful in competing for patient-centered clinical intervention effectiveness funding going forward.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Patient-centered care

- Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)

- Telehealth

- Telemedicine

- US Congress

- Clinical outcomes

- Modern hospital

- Integrated healthcare

Introduction

Improving outcomes through “patient-centered care” has emerged as an important focus of study in clinical practice and research over the past decade [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. While the principles of patient-centered care and community-centered care are found in philosophical writings from ancient times, with the recent paradigm shift toward patient-centered care, physicians have begun to accept that the health and well-being of patients depends upon a collaborative effort between healthcare professionals, patients, and their communities [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

As a result, the idea of active engagement of patients when critical healthcare decisions are being made (e.g., when patients arrive at a crossroads of medical options, where diverging paths have different and important consequences) is becoming increasingly acceptable and part of the standard of care. Of course, the preparedness of patients to fully accept that role and providers’ willingness to promote active engagement is open to question [15]. More importantly, does the medical profession fully understand how unprepared patients and healthcare enterprises are to “fully participate” in the decision-making processes? [16,17,18,19]. What strategies successfully enable patients and their caregivers to optimally provide self-care to manage chronic health conditions?

Questions related to population health literacy in the USA were barely on medical professions’ radar screen prior to 2000 when news that more patients die each year from preventable medical errors than in car crashes shocked the nation [20,21,22]. While the magnitude of this problem remains controversial, there is a general awareness that the poor populational health literacy in the USA, and the relative absence of patient participation in clinical decision-making, may be contributing factors to the medical error problem [23,24,25]. Since the year 2000, beginning with the publication of the US Institute of Medicine’s warnings concerning the possible presence of unacceptably high levels of preventable medical errors within the US healthcare system, not nearly enough has been done to improve patient healthcare education for our K-12 students, as well as future interprofessional team members [16,17,18,19]. The question of whether “the inclusion of sharp-eyed, medically savvy patients on their own personal interdisciplinary healthcare teams would make a difference” will likely need to be addressed through randomized clinical trials.

Latifi’s book The Modern Hospital explains how, and why, patient-centered care is important in modern hospital settings and for improved patient outcomes [26]. Some of his ideas, and those of his co-authors, on patient-centered care can be extended to patients’ homes and even to direct-to-consumer telehealth [1, 2, 26].

The aim of this chapter is to provide perspective on Patient Center Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) extramural dissemination and intervention (D&I) funding for telemedicine and telehealth-related research. Hopefully, this data analysis provides new ideas for PCORI funding priorities, program review criteria, and ways to potentially be successful in competing for patient-centered clinical intervention effectiveness funding going forward.

Background of Dissemination and Intervention Science in the United States

In the USA today, there is an array of funders interested in patient-centered comparative clinical effectiveness research (CER). The list includes, but is not limited to, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the PCORI, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [27,28,29]. The expansion of interest in (D&I) science and the creation of a funding base to support extramural activities in recent years have evolved on several fronts. In recent years, notable extramural-funding programs have been offered by both the NIH and PCORI [27, 30]. The US Congress sets both the NIH and PCORI budget allocations, monitors spending and progress, and for PCORI included a de facto sunset clause in its initial appropriation a decade ago to ensure adherence to the agreed upon vision and mission.

PCORI is a mission-specific medical science/service research enterprise that extends across the borders of drug and medical device innovation; D&I science; patient-centered clinical effectiveness research; and interdisciplinary team-based clinical care delivery. Its website is data-rich and provides clinical researchers and healthcare strategists with up-to-date information on the patient-centered research landscape [27].

Origins of Dissemination and Intervention Science

Historically, NIH programs in D&I science grew out of President Richard M. Nixon’s National Cancer Act (1973) which, for the first time, specified a role for the National Cancer Institute (NCI) that included a focus on cancer control [4]. This resulted in a transition of the cancer control program from a “diffusion of innovations” professional education model to a cancer prevention and control intervention research model. The new Division for Cancer Prevention and Control was charged with developing a framework for cancer control research that included the creation of a linear series of phases from hypothesis generation to development and implementation projects [4, 31, 32]. Beginning in 2005, NIH began soliciting applications to develop an implementation science knowledge base and to build capacity for studies to increase quality and quantity of implementation science knowledge [4].

In 2007, the NIH hosted its first annual conference on D&I research in health. An annual joint NIH and Veterans Administration (VA) D&I science meeting grew to over 1000 participants with over 700 abstract presentations by 2011. This meeting continues to draw a large number of participants each year and is currently co-sponsored by NIH, Academy Health, the Agency for Health Research Quality (AHRQ), PCORI, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the VA. In 2013, the NIH announced the expansion of its D&I research funding to include 15 other NIH institutes, in addition to the NCI, and the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research. In 2014, the NCI began developing important international collaborations primarily focused on training D&I investigators. Within the NCI, although there was growth in implementation science funding from 2001 and 2016, it remains a very small proportion of the overall NCI funding [4].

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute

PCORI is a US-based non-governmental organization created by Congress as part of a modification to the Social Security Act, by clauses in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In comparison to the NIH, which is a very large federal agency with a broad mission to advance biomedical research that has close to $40 billion in annual research funding, PCORI is a relatively small organization with a narrowly focused mandate to advanced patient-centered outcomes research with approximately $300 million in annual research funding [33]. It is charged with leveraging principals of D&I science to move translational and clinical research findings into medical practices of practitioners everywhere, utilizing the results of CER. There has been a close working relationship between the PCORI organization and the NIH leadership since PCORI’s inception [28, 30].

PCORI is supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Trust Fund, of which 80% is provided annually to PCORI to support its research funding and operations. The other 20% is provided to AHRQ and the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) to build data capacity for PCOR. The PCOR Trust Fund receives income each year from: (1) the general fund of the US Treasury; (2) transfers from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) trust funds; and (3) a fee assessed on private insurance and self-insured health plans [4].

An establishing concept for PCORI was that rigorous methodological standards help ensure that medical research produces information that is both valid and generalizable [4, 14, 34, 35]. This goes beyond the typical academic research medical center’s vision, where clinical investigators typically strive to demonstrate validity for the uses of specific therapies and medical devices, but the diffusion of their discoveries into the general public is a secondary objective [7, 36,37,38,39]. Although academic medical centers housed federal-funded “clinical research units” for decades, in the past, community-implementation plans to encourage diffusion into the non-academic population were relatively uncommon.

PCORI was given important tools to accomplish its missions, including an independent, federally appointed Methodology Committee charged with developing methodological standards for patient-centered outcomes research. With oversight of the PCORI Board of Governors, this Methodology Committee, working with outside contractors, is charged with defining and prioritizing research questions [30, 36].

Analysis of the PCORI Telehealth-Related Research Portfolio Database (2010–2019)

PCORI Definitions of Telehealth and Telemedicine

PCORI has adopted a version of telemedicine and telehealth terminology defined by the American Telemedicine Association and the CMS. PCORI defines telehealth as the use of medical information exchanged between sites via electronic communication to improve a patient’s health status. Telehealth includes a growing variety of applications and services using two-way video, smart phones, wireless tools, and other forms of telecommunications technology. The definition requires an exchange of information (bidirectional) across sites (e.g., not within clinics with the use of tablets). Telemedicine seeks to improve a patient’s access to healthcare services by asynchronous data acquisition, transmission and subsequent consultation by a clinician, or alternatively by synchronous two-way, interactive communication, between two or more geographically separated locations where the patient and/or the patient’s in-person clinicians are at one geographic location and the consulting clinicians are at one or more distant geographical locations. The interactive telecommunications equipment includes, at a minimum, audio and video equipment. Telemedicine patient encounters may also utilize peripheral devices such as vital signs measurement or monitoring devices, digital stethoscopes that support transmission of auscultation sounds to remote clinicians, and/or various imaging modalities with video outputs. This definition of telemedicine requires consultation with a licensed medical professional [40] (PCORI helpdesk, Ashlee Horn, personal correspondence, January 27, 2020).

PCORI uses an internally coded portfolio taxonomy for their own website project portfolio search tool filters. PCORI aims at providing researchers with the most comprehensive set of studies that might be relevant to any one of their questions about PCORI’s work. In turn, the PCORI Science team uses this inclusive portfolio dataset as a starting place for PCORI’s own work in portfolio analysis [40] (PCORI helpdesk, Ashlee Horn, personal correspondence, January 27, 2020).

Overview of PCORI Extramural Funding

PCORI provides extramural funding for 22 “Project Types” (Appendix A), ranging from “Engagement Award Conference” to “Research Project.” All of the “telehealth-related funding” was in the “Research Project” category as of December 31, 2019. Eighty-eight out of a total of 655 funded research projects were classified as being “telehealth-related” by PCORI. The current analysis is restricted to examination of those 88 telehealth-related research projects.

PCORI Funding Opportunities

The PCORI website provides detailed information regarding each individual PCORI research project [39]. (Note: PCORI uses neither the terms “grant” nor “contracts” but prefers the term “project” to identify extramurally funded entities.) There have been 149 PCORI Funding Announcements (PFAs) since the inception of the PCORI extramural funding program in 2011.As of January 6, 2020, a total of 1606 projects, of which 655 are classified as “research projects,” had been awarded by PCORI.

PCORI Telehealth-Related Research Project Themes

Generally, PCORI publishes PFAs in three cycles per year for the recurrent themes: “Addressing Disparities; Assessment of Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment Options; Communication and Dissemination Research; Improving Healthcare Systems,” and “Improving Methods for Conducting Patient-Centered Outcomes Research,” constituting an “annual funding cycle.” PCORI also publishes targeted and limited PFAs, many of which may be one-time funding opportunities. There are 51 distinct PFA titles listed on PCORI’s funding webpages for PFAs published through the end of 2019. PCORI’s 1606-project dataset (as of January 6, 2020) lists 45 distinct PFA titles associated with awarded projects. There are 35 distinct PFA titles associated with the subset of 655 awarded research projects [37,38,39,40,41,42].

What percentage of PCORI-funding research projects have been designated “telehealth-related projects”? Of 655 PCORI research projects funded prior to the year 2020, 88, or 13.4% of its research projects, were sub-classified by PCORI as “telehealth-related” projects [42]. Our database search showed that there were an additional 15 projects that included “telemedicine” as an “Intervention Strategy” in their program descriptions but were not included in PCORI’s “Spotlight” list of 88 telehealth-related projects [40, 42, 43]. The reason for this omission is unclear. The PCORI website for telehealth-related research projects includes a listing of the project titles and hyperlinks for the 88 “official” PCORI “telehealth-related” research projects and PCORI’s total funding awarded to these 88 telehealth-related research projects [42, 43].

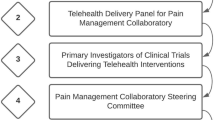

PCORI Telehealth-Related Research Portfolio Analysis (2012–2019)

The PCORI website is rich in information about individual PCORI-funded research projects [42, 43]. We conducted a focused review of the 88 telehealth-related projects. We downloaded into an Excel database the publicly available PCORI research project dataset, and each of the individual telehealth-related project webpages from the PCORI website [42, 43]. These information sources included: (1) the PFA under which the project was awarded; and (2) attributes such as: the specific category, or categories that speak to the general goals for the specific program; organization; year awarded; actual or expected end date; budget; completion status; health conditions studied; patient population studied; intervention strategies; time frame; and, for the completed projects, articles published [42].

According to PCORI personnel, the information for the public PCORI website database was created by the PCORI organization using a process developed by PCORI staff with the help of an independent contractor. This involved a “systematic analysis and coding of PCORI’s funded awards, based on a read of the research plan” [40] (PCORI Help desk, August 2019). The specific health conditions, patient populations, and intervention strategies studied as part of individual research projects are listed in the individual project profiles. For our analyses, we used data explicitly listed in the profiles carefully avoiding extrapolating based on assumptions of what we thought might be additional relevant categories for individual projects. Project funding amounts used in our analysis were included in the PCORI project profiles [42].

Telehealth-related D&I projects totaled $381 million dollars [42]. Included in the PCORI Telehealth Research Project Portfolio that lists 88 projects are 35 projects for which PCORI coded “Telemedicine” as one of their intervention strategies, and 53 projects that do not include “Telemedicine” as a PCORI-coded intervention strategy. The official telehealth-related component, 88 projects, represents 19% of total PCORI project research funding (2012–2019) and 13% of the total number of PCORI research projects. Since PCORI, and the awarded “telehealth-related” research projects, use the terms “telemedicine” and “telehealth” and a number of “telehealth-related” terms somewhat interchangeably, the complete set of telehealth-related projects is not retrievable by searching on any one of these terms thus requiring reading through entire project webpages in order to determine exactly how a project is “telehealth-related” in some instances.

Of the 88 telehealth-related research projects, 34.1% (n = 30) were listed as “completed,” as of December 31, 2019 [43]. For the record, the 88 telehealth-related research projects, per individual project webpages and the data set downloaded from PCORI, had an exact total awarded funding of $379,591,036 and an average awarded budget of $4,313,535 (ranging from $716,243 to $15,201,613 for individual projects).

PCORI Research Project Themes

Telehealth-related research projects have been awarded under the following 13 thematic PFAs: (1) Assessment of Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options; (2) Communication and Dissemination Research; (3) Addressing Disparities; (4) Patient-Powered Research Networks (PPRN) Research Demonstrated Projects; (5) Symptom Management for Patients with Advanced Illness; (6) Improving Healthcare Systems; (7) Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for Delivery for Pregnant Women with Substance Use Disorders Involving Prescription Opioids and/or Heroin; (8) Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis; (9) Management of Care Transitions for Emerging Adults with Sickle Cell Disease; (10) Partnerships to Conduct Research with PCORnet (PaCR); (11) Pragmatic Clinical Studies to Evaluate Patient-Centered Outcomes; (12) Community-Based Palliative Care Delivery for Adults with Advanced Illnesses and their Caregivers; and (13) Psycho-social Interventions with Office-Based Opioid Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder [41, 42]. These 13 “research themes” might have influenced the choices of some investigators regarding: (1) their interest in competing in the PCORI extramural funding process; and (2) the subject matter and research questions they chose to study.

It is interesting to note that our search of the 149 PFAs issued between 2011 and 2019 found the word “telemedicine” appears only in the “Improving Healthcare Systems” PFA, which was offered in 18 different funding cycles. The word “telehealth” appeared in only two targeted PFAs: “Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis” and “Management of Care Transitions for Emerging Adults with Sickle Cell Disease.” A number of other telehealth-related terms appeared in various PFAs including, but not limited to, mHealth, mobile health, teleconference, telemonitoring, telephonic, teledelivery, telecare, telerehabilitation, and remote monitoring. Therefore, identifying telemedicine activities or telehealth funding opportunities can require searches on a broad set of telemedicine- and telehealth-related terms in addition to using umbrella terms such as “telehealth” and “connected health.”

Figure 6.1 shows our tabulation of the percentage of the telehealth-related research project funding awarded to the 88 telehealth-related projects in each of the 13 PFA themes that telehealth-related research projects were awarded under. There is telehealth-related research project funding in 37% of the 35 distinct PFA themes under which the total of 655 research projects were awarded. The PFA theme with the most funding awarded to telehealth-related research projects is “Pragmatic Clinical Studies to Evaluation Patient-Centered Outcomes” (29%). “Symptom Management for Patients with Advanced Illnesses” had the least funding (1%). Low funding areas (0–5% of the total telehealth-related research) may represent areas of special opportunity for telehealth investigators moving forward.

The “Improving Healthcare Systems” (IHS) PFA “seeks to fund CER that addresses the same areas as those addressed by IOM” (Institute of Medicine; recently renamed the “National Academy of Medicine”). “IOM has addressed key aspects of systems improvement, including,” the aims of, “making care: Accessible, Effective, Patient-centered, Timely, Efficient, Safe, Equitable, and Coordinated.” Telemedicine is included in the IHS PFA as a “technology intervention” that research projects could potentially apply to achieve the IOM aims [41] (PCOR’s Cycle 32,019 Funding Cycle; page 23).

Health Conditions, Patient Populations, and Intervention Strategies: Telehealth-Related Content Analysis (2010–2019)

Health Conditions

Five hundred twenty-eight of the 655 PCORI research projects, including the 88 telehealth-related projects, were coded by PCORI with one or more health conditions. The remaining 127 research projects were not coded with any health condition. Together, the 655 research projects contained a total of 139 unique health condition codes assigned by PCORI. There are 27 general health condition categories and 112 specific conditions coded as subcategories of the general health condition categories. Many research projects involved more than one health condition. The three highest frequency general health conditions in the telehealth-related project subset of PCORI research projects are: mental/behavioral health (n = 32), which included diseases such as substance addiction/abuse and depression; cardiovascular diseases (n = 21) including hypertension and stroke; and nutritional and metabolic disorders (n = 17) including diabetes and obesity (Fig. 6.2). In general, PCORI codes for both the general health condition categories and any specific disease subcategories for each research project.

Bar graph representing the number of times (frequency) each of the 23 “general health conditions” appears in the 88 PCORI-funded telehealth-related research projects [37]

Patient Populations

Of the 13 categories of patient populations identified by PCORI as being disproportionately at risk for poorer healthcare outcomes, the groups most frequently targeted by telehealth-related research projects were Racial/Ethnic Minorities (n = 69), Low-Income Individuals (n = 35), and Women (n = 28) (Fig. 6.3).

Bar graph representing the percentages of 79 telehealth-related research projects that address each of the 13 PCORI-specified “Patient Populations of Interest.” PCORI has not specified the target population(s) for the remaining 9 of the 88 telehealth-related research projects [37]

Levels of Funding

PCORI funding for telehealth-related research projects averaged $1,911,786 for 2012, 2013, and 2014 combined, $3,826,744 for 2015 and 2016 combined, and $7,954,570 for 2017 and 2018 combined (Fig. 6.4). While these increases have not been steady, there is an overall upward trend. The average project award for 2017 and 2018 combined is more than quadruple the average award for 2012, 2013, and 2014 combined. The average budget for projects awarded in 2019 dropped to $5,013,909, perhaps reflecting uncertainty over reauthorization of the PCORI program funding until December 2019.

Line chart representing the average budget awarded to telehealth-related research projects each year by PCORI from 2012 to 2019. The “n” represents the number of projects awarded each year [40]

Of the 88 telehealth-related research projects (Fig. 6.5), 23 (26%) had budget awards between $0.0 and $2.0 million, 38 (43%) had budget awards between $2.0 million and $5.0 million, 18 (20%) had budget awards between $5.0 million and $10.0 million, and 9 (11%) had budget awards that exceeded $10.0 million dollars.

PCORI Research Study Designs

The PFAs identified, among other parameters, the general research theme (focus) and expected study design. For example, “Assessment of Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options” projects used randomized trials in clinical settings to compare the outcomes of at least two different healthcare options to address “gaps in the current evidence base” so patients could decide the most effective option for their individual circumstances [43]. In the years 2012 through 2019, telehealth-related research projects were awarded most commonly under the PFA themes for “Improving Healthcare Systems” (n = 24), “Addressing Disparities” (n = 17), and “Assessment of Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options” (n = 17). During the same time period, “Addressing Disparities” with average funding awarded per project of $2,331,198 and “Assessment of Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options” ($2,328,550) were two of the three PFA themes with the lowest average awarded budgets, while the PFA themes with the highest average awarded budgets were “Community-Based Palliative Care Deliver for Adult Patients and their Caregivers” (n = 2, average budget awarded of $12,372,111) and “Pragmatic Clinical Studies to Evaluate Patient-Centered Outcomes” (n = 9, average budget awarded $12,057,672) (Fig. 6.6).

Bar graph representing the frequency of PCORI-funded telehealth-related research projects in 13 PFA themes from 2012 to 2019. Numbers of projects in each group are listed, in white, at the left ends of each of the dark bars. Average dollar amounts for budgets awarded to each project within a PFA group are adjacent to each bar at the right. PFAs are listed in descending order (top to bottom) according to average project budget awards

Intervention Strategies

Included in the “PCORI Telehealth-Related Project Portfolio” are projects with as many as nine intervention strategies as coded by PCORI and its consultants. Thirty-five projects were coded specifically with “Telemedicine” as one of their intervention strategies. Figure 6.7 shows the percentage of telehealth-related projects utilizing each of the 15 “core” intervention strategies referenced by PCORI. The three most frequent intervention strategies associated with telehealth-related research projects were “Training and Education,” “Technology,” and “Other Health Services Interventions.”

The 88 telehealth-related projects utilized one, or some combination, of the PCORI designated core “Intervention Strategies”: Behavioral Interventions, Care Coordination, Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Device Interventions, Drug Interventions, Incentives for Behavior Change, Other Clinical Interventions, Other Health Service Interventions, Patient Navigation, Screening Interventions, Shared Decision-Making, Technology Interventions, Telemedicine, and Training and Education Interventions. On average, telehealth-related projects applied four to five intervention strategies (mean = 4.69; range 1–9).

Location and Organization

The majority of telehealth-related research projects were conducted at research universities, with others at non-university hospital systems and independent research institutes. With regards to location, organizations in 26 states received funding for telehealth-related projects (Fig. 6.8). California had the most telehealth-related projects at 14, followed by Massachusetts at 12 and Pennsylvania at 9. The current state and current organization specified by PCORI as of January 6, 2020, for each telehealth-related project were utilized for these tallies. Some telehealth-related projects included a descriptive footnote from PCORI that indicated that the project had originally been awarded to an organization in one state but then had been transferred to a new organization, often in a different state. From 2012 through 2019, the University of California (all campuses) was awarded six telehealth-related projects (three of which went to the University of California, San Francisco), and the Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, MA, was awarded five telehealth-related projects. The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY, and University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, were each awarded three telehealth-related projects. One project was awarded to the Sinai Health System (Toronto, Canada) with its study slated to recruit subjects in Toronto, Canada; Chapel Hill, North Carolina; and Chicago, Illinois.

Publications

In addition to PCORI’s requirements for posting the final research report and final study protocol publicly on its website, PCORI encourages and permits publication of PCORI-funded research in any journal at any time [44]. PCORI requires that the awardees make their peer-reviewed publications publishing findings from PCORI research available in PubMed Central. PCORI will, upon request from the project awardee, pay the fees to make peer-reviewed articles published in journals freely available to the public [45]. Of the 30 completed PCORI telehealth-related research projects, 21 had their results published in peer-reviewed medical journals as of December 31, 2019. These journals are listed in Table 6.1. We queried the InCites Journal Citation Reports database to obtain the 2018 impact factor and five-year impact factor (as of 2018) for each of the journals in Table 6.1 [46, 47].

Discussion

The original Congressional appropriation that created PCORI in 2010 provided 10 years of funding, expiring in 2019. In late 2019, the Congress re-appropriated federal funding for the PCORI foundation providing it with another 10 years of funding through 2028. The re-appropriate reflects the endorsements of PCORI by diverse constituencies including federal agencies, foundation, industry, and within the healthcare delivery community to attest to the successes of the strong founding leadership of PCORI [48,49,50].

PCORI was created to fund research projects focused on PCOR CER to provide high-quality, unbiased evidence enabling optimal decision-making between patients and caregivers, facilitate efficiency of healthcare systems at all levels of organization, and eliminate healthcare disparities for disadvantaged and minority groups [14, 47, 48]. A key Congressional mandate required patient-centeredness (the involvement of the patient in the management of their own healthcare) and collaboration with community stakeholders to ensure that research questions and study design would be relevant, feasible, and sustainable so that patients would have the ability to make the best evidence-based healthcare decision for themselves [6,7,8, 10,11,12,13,14]. PCORI-funded research projects involve comparing risks and benefits of at least two healthcare options, engage patients and other relevant stakeholders, follow methodology guidelines to ensure quality comparative effectiveness trials, and seek to improve healthcare outcomes—particularly in terms of conditions that place a heavy burden on society and populations disproportionately at risk for poor healthcare outcomes [48]. Additionally, much of the PCORI research has focused on improving CER methods and developing a network (PCORnet) to continue to advance patient-centered research capacity and infrastructure on a broader scale [45]. An additional expectation of PCORI-funded research was the publication of results in high-caliber academic journals [45, 46].

In line with PCORI’s defined goals of using CER trials to establish a strong evidence base, the 88 telehealth-related research projects analyzed for this study utilized PCOR CER to study telehealth’s impact on patient outcomes.

With regards to the health conditions studied, the most frequently referenced conditions included mental/behavioral health, nutritional and metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular diseases that disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minorities and low-income populations, and lack of insurance, lack of diversity among care providers, lack of culturally competent providers, and language barriers all pose as obstacles to these groups receiving adequate care [50, 51]. The leading causes of death in the USA in 2016, as outlined by the CDC, were heart disease, cancer, accidents, chronic lower respiratory diseases, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, nephrosis, and suicide [52]. In line with what we have already discussed about PCORI’s focus on studying conditions that impact a large number of people and place a large burden on society, it seems logical that those were the most frequently studied categories of health conditions by PCORI awardees.

PCORI has effectively shown that there is value in having a term-limited quasi-governmental agency with a laser-sharp focus on promoting and supporting D&I research and education. Building a sunset clause in 2010 into the original Congressional funding undoubtedly encouraged the PCORI organization to stay on mission over the past decade. Community input into decision-making was strongly encouraged. Academia was forced to look outside of its own walls and seek council on what is important to the general public, the major consumers of healthcare. The recent re-appropriation of funding for another 10 years is good news and should be taken as an endorsement of the trajectory that PCORI is pursuing to identify and encourage implementation of new solutions to old problems in the delivery of healthcare [53].

While PCORI is filling a critical gap in the medical services innovation cycle by stimulating the creation of a sustainable, distributed D&I research enterprise that provides strong linkages between the PCORI-funded evidence-based clinical research teams and largely academic healthcare delivery systems, it remains to be seen how many of the improvements in patient outcomes identified by PCORI-funded research actually become incorporated into community healthcare practices. Only time will tell if PCORI actually “improved patient care and reduced the burden that some of our country’s most pressing healthcare issues impose on individuals, their families, and the healthcare system,” a commitment made to the US Congress by the PCORI Leadership [49, 50].

Finally, additional work is needed to establish the origins of the inclusion of telehealth-related projects in the PCORI telehealth-related research project portfolio. It is apparent that telehealth clinical research has benefitted significantly from PCORI funding—approximately $381 million dollars to date. The next step should be studying the long-term effects and outcomes of these projects. In particular, how does a PCORI-funded project change the current practice and does it advance improvements of clinical outcomes? Much remains to be done! (Fig. 6.9).

Printouts of the mountain of Excel spreadsheets that formed the basis for the PCORI portfolio analysis described in this chapter. Left to right: Sir William Osler Summer Fellow Camryn Payne at the ATP headquarters, at The University of Arizona, Tucson, assembled this large database from publicly available information at the PCORI website and through the PCORI “Help Desk,” in the summer of 2019. Michael J. Holcomb, the ATP’s’ Associate Director for Information Technology, worked closely with Dr. Weinstein to validate Camryn’s data, and to study PCORI’s entire research project portfolio. Ronald S. Weinstein, MD, Founding Director of the ATP and of the ATP’s Sir William Osler Summer Program which he founded as a young Department of Pathology Chairman at Rush Medical College in Chicago, in the summer of 1978. He relocated the Osler Program to The University of Arizona, in Tucson, when he changed pathology chairs in order to continue his research on P-glycoprotein’s role in multidrug resistance in cancer cells at the Arizona Cancer Center, in Tucson. This picture marked the 40th anniversary of Dr. Weinstein’s Sir William Osler Summer Program for College and High School Students. Hundreds of college and high school students had benefitted from his Osler Summer Programs in Chicago and Tucson. Camryn Payne, a Tucson native, had finished her second year as a pre-medical college student at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

Change history

14 June 2021

R.Latifi at al. (eds.), Telemedicine, Telehealth and Telepresence, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56917-4

References

Daniel CY, Latifi R. Navigating and rebuilding. In: The modern hospital: patients centered, disease based, research oriented, technology driven. New York: Springer; 2019. p. 31.

Latifi R, Daniel CY. The modern hospital: patient-centered and science based. In: The modern hospital: patients centered, disease based, research oriented, technology driven. New York: Springer; 2019. p. 85–92.

Brownson RC, Golditz GA, Proctor EA, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health. Translating science into practice. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Kerner J, Glasgow RE, Vinson CA. A history of the National Cancer Institute’s support for implementation science across the cancer control continuum. Context counts. In: Chambers DA, Vinson CA, Norton WE, editors. Advancing the science of implementation across the cancer continuum. New York: Oxford University Press; 2019. p. 8–20.

Fernandez ME, Mullen PD, Leeman J, Walker TJ, Escoffery C. Evidence-based cancer practices, programs, and interventions. In: Chambers DA, Vinson CA, Norton WE, editors. Advancing the science of implementation across the cancer continuum. New York: Oxford University Press; 2019. p. 21–40.

Basch E, Aronson N, Berg A, et al. Methodological standards and patient-centeredness in comparative effectiveness research: the PCORI perspective. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1636–40.

Comparative effectiveness research: activities funded by the patient-centered outcomes research trust fund. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-311.pdf. Last accessed 23 Feb 2020.

Fischer MA, Asch SM. The future of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2291–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05324-9.

Tauber AI. Patient autonomy and the ethics of responsibility. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005.

Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1513–4.

Selby JV. Interview: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute seeks to find out what works best by involving ‘end-users’ from the beginning. J Comp Eff Res. 2014;3(2):125–9. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.13.94.

Selby JV, Forsythe L, Sox HC. Stakeholder-driven comparative effectiveness research: an update from PCORI. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2235–6.25-9.

Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard TS, Paez KA. The PCORI engagement rubric: promising practices for partnering in research. Ann Family Med. 2017;15(2):165–70.

Clinical Effectiveness and Decision Science. www.pcori.org/about-us/our-programs/clinical-effectiveness-and-decision-science. Last accessed 23 Feb 2020.

Kindig DA, Panzer AM, Nielsen-Bohlman L, editors. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. p. 1–345.

Schmitt MH, Gilbert JH, Brandt BF, Weinstein RS. The coming of age for interprofessional education and practice. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):284–8.

Weinstein RS, Lopez AM. Health literacy and connected health. Health Aff. 2014;33(6):1103B.

Weinstein RS. Reinventing the US Institute of Medicine: a second coming. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):e1–2.

Weinstein RS, Waer AL, Weinstein JB, Briehl MM, Holcomb MJ, Erps KA, Holtrust AL, Tomkins JM, Barker GP, Krupinski EA. Second Flexner Century: the democratization of medical knowledge: repurposing a general pathology course into multigrade-level “gateway” courses. Acad Pathol. 2017;4:2374289517718872.

Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National academy press; 2000.

Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff. 2002;21(3):80–90.

Knebel E, Greiner AC, editors. Health professions education: a bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

McDonald CJ, Weiner M, Hui SL. Deaths due to medical errors are exaggerated in Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2000;284(1):93–5.

Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

Rodwin BA, Bilan VP, Merchant NB, Steffens CG, Grimshaw AA, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG. Rate of preventable mortality in hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;21:1–8.

Latifi R. The modern hospital: patients centered, disease based, research oriented, technology driven. New York: Springer; 2019.

Primer: PCORI Background, Funding Streams, and Reauthorization. www.pipcpatients.org/blog/primer-pcori-background-funding-streams-and-reauthorization. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

Clancy C, Collins FS. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute: the intersection of science and health care. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(37):37cm18.

Washington AE, Lipstein SH. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute—promoting better information, decisions, and health. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e31. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1109407.

Selby JV, Lipstein SH. PCORI at 3 years—progress, lessons, and plans. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):592–5.

Greenwald P, Cullen JW. The scientific approach to cancer control. CA Cancer J Clin. 1984;34(6):328–32.

Devita V, ed. Cancer control objectives for the nation: 1985–2000. NCI Monogr. 1986;(2):vii.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Funding: FY 1994-FY 2020. Updated January 22, 2020. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43341.pdf. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, et al. Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev Sci. 2005;6:151–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y.

Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2(1):42.

PCORI Board of Governors. https://www.pcori.org/about-us/governance/board-governors. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

What & Who We Fund. www.pcori.org/funding-opportunities/what-who-we-fund. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

About Our Research. www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research. Last accessed 23 Feb 2020.

Explore Our Portfolio of Funded Projects. https://www.pcori.org/research-results?f%5B0%5D=field_project_type%3A298. Last accessed 22 Jan 2020.

PCORI Help Center. https://help.pcori.org/hc/en-us/requests/new. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

PCORI Research Spotlight on Telehealth. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Research-Spotlight-Telehealth.pdf. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

Telehealth-related PCORI-Funded Research Projects. https://www.pcori.org/topics/telehealth/telehealth-related-pcori-funded-research-projects. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

Closed PCORI Funding Announcements. https://www.pcori.org/funding-opportunities/awardee-resources/closed-pcori-funding-announcements. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

PCORI-Frequently Asked Questions. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/peer-review/peer-review-faq. Last accessed 24 Feb 2020.

PCORI Public Access to Journal Articles Presenting Findings from PCORI-Funded Research Policy. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Policy-Public-Access-to-Journal-Articles-Presenting-Findings-from-PCORI-funded-Research.pdf. Last accessed 24 Feb 2020.

Journal Citation Reports. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/journal-citation-reports/. Last accessed 24 Feb 2020.

A Comparative Trial of Improving Care for Underserved Asian-Americans Infected with HBV. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2014/comparative-trial-improving-care-underserved-asian-americans-infected-hbv. Last accessed 2 Feb 2020.

Healthcare Delivery and Disparities Research. www.pcori.org/about-us/our-programs/healthcare-delivery-and-disparities-research. Last accessed 3 Feb 2020.

Keller AC, Flagg R, Keller J, Ravi S. Impossible politics? PCORI and the search for publicly funded comparative effectiveness research in the United States. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2019;44(2):221–65.

PCORI Statement on Congressional Reauthorization of Funding. https://www.pcori.org/news-release/pcori-statement-congressional-reauthorization-funding. Last accessed 3 Feb 2020.

Mental Health Disparities. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2759796/. Last accessed 3 Feb 2020.

FastStats – Leading Causes of Death. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. Last accessed 3 Feb 2020.

Weinstein RS, Holcomb MJ. Select healthcare transformation library. Healthcare Transform Artif Intell Autom Robot. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/hwR.2019.0009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix A: PCORI’s 22 “Types of Projects”

Appendix A: PCORI’s 22 “Types of Projects”

1. Dissemination and Implementation Project |

2. Engagement Award Conference |

3. Engagement Award Conference, Conference: Dissemination |

4. Engagement Award Project |

5. Engagement Award Project, Dissemination Project |

6. Implementation of Effective Shared Decision-Making Approaches Project |

7. Implementation of Findings from PCORI’s Major Research Investments |

8. Implementation of PCORI-Funded PCOR Results (Limited Competition Project) |

9. Other Evidence Products |

10. PCORnet Coordinating Center Phase II |

11. PCORnet Initiative on Health Plan/System Data Partnerships (A Stepwise Approach to Collaboration) |

12. PCORnet: Clinical Data Research Networks (CDRN) Phase I |

13. PCORnet: Clinical Data Research Networks (CDRN) Phase II |

14. PCORnet: Patient Powered Research Networks (PPRN) Phase I |

15. PCORnet: Patient Powered Research Networks (PPRN) Phase II |

16. Pipeline to Proposal, Tier A |

17. Pipeline to Proposal, Tier I |

18. Pipeline to Proposal, Tier II |

19. Pipeline to Proposal, Tier III |

20. PPRN Limited Competition Award |

21. Research Infrastructure Project |

22. Research Project |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Weinstein, R.S. et al. (2021). Telehealth Dissemination and Implementation (D&I) Research: Analysis of the PCORI Telehealth-Related Research Portfolio. In: Latifi, R., Doarn, C.R., Merrell, R.C. (eds) Telemedicine, Telehealth and Telepresence. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56917-4_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56917-4_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-56916-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-56917-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)