Abstract

The benefit of art and creativity in improving health and well-being across all age groups is being increasingly recognized. This study reports on the logistics and evaluation of an outdoor art project within a residential care home in Scotland that aimed to involve residents, their families, and staff in a creative experience to benefit their well-being. Initial designs were developed by a professional artist with the final design being chosen by residents and titled the “Tree of Many Colours.” The design encompassed 57 individual clay tiles; the artist led the creative process over a period of a month. Project evaluation was undertaken using a combination of qualitative and video-based observational research (VOR) through questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and video capture. The evaluation highlighted five key themes and demonstrated the main benefits derived by residents: learning new skills; self-belief; surprise at their own creative ability; excitement and fun. As a result of the project, staff were more confident and eager to use creative activities. The project has provided a focal piece of art for the home and engendered intergenerational community spirit, bringing staff, residents, and their families together. The model can be replicated and has the potential to be adopted in other settings.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Health promotion

- Art

- Creativity

- Wellbeing

- Care settings

- Intergenerational

- Aging

- Dementia

- Alzheimer’s disease

1 Introduction

In 2017, the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Arts, Health, and Wellbeing published “Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing,” providing compelling evidence on how the arts and culture can make a positive impact in tackling health inequalities and improving health, well-being, and quality of life for people of all ages. Within this report, Sir Michael Marmot, director of the Institute of Health Equity, University College London, acknowledges this by stating: “The mind is the gateway through which the social determinants impact upon health and this report is about the life of the mind. It provides a substantial body of evidence showing how the arts, enriching the mind through creative and cultural activity, can mitigate the negative effects of social disadvantage (p. 2).” The growing awareness of the powerful contribution that the arts can make to support health and well-being across age groups is leading health and social care professionals to seek practical guidance and support in developing appropriate evidence-based programs.

This chapter describes an arts-based initiative in a care home setting in Scotland that was designed to promote health and well-being through creative expression, social inclusion, and the aesthetic beautification of space for residents ranging in age from 48 to 100, 50% of whom have been diagnosed with dementia. The project was designed to involve residents, their families, and staff to promote inclusion, create a piece of public art, and provide lasting memories.

2 Art, Health, and Well-being

The term “the arts ” commonly includes diverse forms of expression such as poetry, storytelling, drama, theater, music, visual arts (such as painting and sculpture), and cultural pursuits including visiting museums and art galleries. The value of the arts in the promotion of health and well-being is increasingly being recognized both within the “medical model” and more recently within non-medical settings (Seligman 2011). “Art therapy ” over the past decade has been used in health care settings as a therapeutic tool for an array of health conditions including mental illness, cancer, autism, pain management, and dementia, and is only delivered by qualified art therapists (Elkis-Abuhoff and Morgan 2019). Such therapies are described by the British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT 2018) as strategies within the wider field of psychotherapy, which incorporate art and creative expression as the primary tool for communication. Art is not used for diagnosis but as a mechanism for processing emotions and experiences, which may be confusing or distressing to talk about.

Coburn et al. (2017) suggest that health, well-being, and the environment are symbiotic and that by working strategically, sustainable health-promoting environments can influence people’s well-being. With the increasing need for prevention of ill health, the value of beautiful spaces on improving health and well-being has the potential to support individuals and society as a whole (Coburn et al. 2017). Good environmental design can enable healthier lifestyles and improved well-being, and there is the potential to achieve substantial long-term savings in health and social care costs as a result (CABE 2009; Coburn et al. 2017; Jones and Yates 2013). The beautification of living and recreational spaces has long been recognized, dating back to the Palaeolithic age with cave drawings. There were also early indications of the benefits of art in relation to health, although these ideas came from philosophers rather than physicians (Fancourt 2017). The benefits of art, creativity, and culture are associated with many factors, including supportive environments both indoors and outdoors, thus offering an innovative approach to public health by providing restorative and regenerative opportunities (Chatterjee et al. 2018; Cutler 2013; see also Chap. 1, this volume). The powerful impact of beautiful spaces on healing and well-being is gaining recognition with the term “Healing Built Environment” (HBE), used to describe “…healthcare buildings that (1) reduce the stress levels for all healthcare building users; and (2) promote health benefits for users” (Zhang et al. 2018, p. 747).Footnote 1 This is a relatively new area of research, and Zhang and colleagues propose a concept called the “environment-occupant-health framework” (E-O-H) that they suggest could be of value to a wide range of professionals, offering the opportunity to “…provide a common language between clinicians, planners, designers and patients when a healthcare building/space is built or refurbished” (Zhang et al. 2018, p. 761).

In 2017, Age UK created an “Index of Wellbeing in Later Life” to provide a comprehensive and systematic way to measure well-being for adults over the age of 60, examining five key domains: personal, social, health, resources, and local. The most notable finding was that creative and cultural participation contributed most significantly to well-being out of all 40 factors explored (Green et al. 2017). The Index also clearly demonstrated that “…the importance of maintaining meaningful engagement with the world around you in later life—whether this is through social, creative or physical activity, work, or belonging to some form of community group” is vital to well-being (Green et al. 2017, p. 12).

3 Social Isolation and Loneliness

There are many reasons why people become isolated. In addition to those associated with becoming elderly, Wilkinson and Pickett (2018) suggest these reasons include societal changes, family breakdowns, ill health, and financial difficulties. A recent report suggests that socially isolated people are 3.5 times more likely to enter local-authority-funded residential care (No Isolation, 2019).

There is now a growing body of evidence demonstrating the effect that isolation and loneliness have on mortality, indicating comparability with risk factors like smoking and obesity. Loneliness can affect both physical and mental health with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, cognitive decline, depression, and dementia (Aiden 2016; Holt-Lunstad et al. 2010; Valtorta et al. 2016). In the UK alone, there are over 1.2 million chronically lonely people, and this number is set to rise with the aging population (Age UK 2016). It is evident that being part of a social network and having a sense of belonging and self-worth are crucial for health and well-being regardless of age. Owen (2014, p. 27) suggests that “…the sense of loneliness that manifests itself in care homes often begins when older people are still living in their own homes.” A study conducted in England between 2002 and 2015 exploring loneliness in the care home found that by tackling loneliness in the aging population, well-being could be enhanced, thus delaying and potentially reducing the demand for residential care (Hanratty et al. 2018).

4 The Aging Population, Dementia, and Alzheimer’s Disease

The United Nations (2018) estimated that in 2017, 13% (962 million) of the global population was over the age of 60. The UK Office of National Statistics (ONS) reports that its country’s population is growing due, in part, to aging, and that the percentage of people over age 65 is increasing, estimating that it will continue to grow to almost a quarter of the population by 2045. This aging population boom, however, presents new challenges. Dementia is regarded as one of the biggest twenty-first-century health and social care issues (ONS 2017). The World Health Organization defines dementia as “…a syndrome in which there is deterioration in memory, thinking, behavior and the ability to perform everyday activities” (WHO 2017 para. 1–2). The most common type of dementia is found in those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. In the UK, 850,000 people are affected by Alzheimer’s Disease including 40,000 people under the age of 65, and the incidence of dementia is predicted to increase to 1.6 million by the year 2040 (The Alzheimer’s Society 2018). The impact of the disease on people’s lives has been explored through in-depth interviews with carers and dementia sufferers (Carter and Rigby 2017). The research highlights that dementia is still misunderstood and viewed negatively, potentially increasing feelings of low self-worth and isolation for both sufferers and carers. The Alzheimer’s Society urges everyone, not only health and social care providers, but society as a whole, to recognize the problem and for substantial funding to be allocated for research and improved social care provision.

5 The Arts and the Care of Older Adults

The importance of health promotion and disease prevention in the aging population is fundamental, and the arts can play a significant role by reducing social isolation, increasing confidence, improving mobility, and building community capacity (Age UK 2017). Positive well-being can lead to more fulfilling and flourishing communities that can in turn delay or indeed prevent entry into the care home setting by enabling individuals to remain at home (Windle et al. 2016). Aging can lead to a range of health challenges including dementia, brittle bones, changing gait, diminished eyesight, hearing loss, and reduced self-confidence as a result (Oliver et al. 2014). A report published by Collective Encounters 2013 —“Arts and Dementia: bringing professional arts practice into care settings”—highlights the extensive research undertaken in exploring the benefits of engaging with participatory arts in the social context; it demonstrates the benefits of participatory arts in providing creative activities, facilitating social interaction, enabling choice, and supporting personal development within social care settings for dementia sufferers.

The value of art and creativity in the care home setting is recognized as being of importance to residents’ physical and mental well-being and their overall quality of life. Taking part in activities, whether familiar or new, provides opportunities to gain knowledge, boost confidence, and connect in different ways (Speer and Delgado 2017). Such activities are not only rewarding but also offer feasible ways of providing excellence in care (Cutler et al. 2011). Creativity has no barriers, is inclusive, is non-judgmental, and offers individuals and communities unique opportunities to participate regardless of age, disability, social challenges, and gender (Potter 2016). The use of arts in health has flourished over recent decades, and its potential is gaining recognition for what was once regarded as a fringe activity (Fancourt 2017). Health promotion enables people to increase control over and improve their health and well-being in a wide variety of ways, and participation in the arts gives individuals the opportunity to socially connect, learn new skills, and most importantly express themselves creatively (APPG 2017; Fancourt 2017; WHO 1986).

6 The Project: “Tree of Many Colours”

6.1 The Care Home Setting

The village of Aboyne, Aberdeenshire, Scotland was the geographic location for this innovative outdoor art project. Aboyne is situated within the Marr area, which is one of six administrative areas within Aberdeenshire Council, with a population of 2910, of which 16.7% is over the age of 65 (Aberdeenshire Council 2016). Aboyne is one of three villages that encompasses Royal Deeside, and its economy is largely dependent on land-based enterprises, agriculture, and tourism.

The idea for the project evolved after Michelle Riddock, the manager of Allachburn Care Home in Aboyne, and her assistant managers visited a new purpose-built residential care home. To assist with the transition process, the manager of the new care home engaged an artist to help residents express how they felt about leaving their previous residential care home and moving to the new one. The project was titled “Moving Out, Moving In,” and a unique canvas was created capturing residents’ feelings, interests, memories, and personalities. It was this project that inspired the assistant managers to explore a creative outdoor project for Allachburn.

6.2 Project Aim and Objectives

The aim of the project was to offer residents and staff a meaningful, stimulating, and creative experience. The project had three main objectives:

-

1.

To explore whether participation had any impact on the health and well-being of residents and staff

-

2.

To increase staff awareness of the value of arts-based activities in delivering participant-centered care

-

3.

To raise awareness of the project within the wider community through engagement and sponsorship

6.3 Project Team

The project took more than six months of planning, involving the leadership and collaboration of the following partners:

-

Michelle Riddock, Allachburn Care Home Manager (and other Allachburn staff)

-

Gil Barton, Facilitator and Health and Well-being Consultant

-

Ian Robertson, Artist

-

Margaret O’Connor, Chief Executive at Art in Healthcare (AiH), a charity based in Edinburgh

-

Beth Bidwell, Ceramic Technician at Scottish Sculpture Workshop (SSW), Lumsden, Aberdeenshire

Gil Barton had been asked to assist with ideas for a creative outdoor project through her volunteer role as trustee of a local charity (Mid Deeside Community Trust).

6.4 Funding

The funding for the project was a combination of sponsorship; fundraising by the Care Home Family (CHF); and the goodwill of staff, family, and friends. The available funding was insufficient to cover the full costs and as a result, the project team agreed to run this as a pilot project, absorbing any outstanding costs.

6.5 Project Planning

The manager of Allachburn was open to ideas and innovative in her approach to running the home, which was a key factor in the development stages. One of the critical aspects of a successful arts-in-health project is positive engagement with participants and staff, which can be challenging particularly within a health care setting and/or when working with a vulnerable group of individuals (The Welsh NHS Confederation 2018). The early involvement of the CHF resulted in much interest, and this engagement brought the project to life during the planning phase. The manager consulted with residents, their families, and staff to determine if there was interest; once interest was established, a Residents’ Representative Group was formed called “Allachburn Art Project” . Any health and safety considerations should be addressed at the early outset of the planning stage to ensure adoption of safe practices (Fancourt 2017), and the Representative Group and project team worked together to ensure this.

The facilitator, being locally based, liaised with all partners to ensure the project was on track. Working in Aberdeenshire rather than Edinburgh or Glasgow was new for AiH, and it was important that the facilitator liaised effectively with all partners. The artist was not locally based, presenting a further logistical challenge. Concise project planning was necessary, and the construction of a logic model framework ensured that the key components were integrated and outcomes were focused (Cohen et al. 2014; Fancourt 2017). To ensure maximum opportunity for participants, a total of eight workshops were planned throughout August on Tuesdays and Wednesdays from 10–12 AM and 2–4 PM each day. In planning the workshops, it was important to take into account the normal routines and regular activities of the care home itself.

6.6 Practical and Creative Considerations

The most suitable medium for the project was clay, requiring extensive planning by the artist, and this was where the support of the ceramic technician was crucial. Practically, it was important that the tiles were of a regular thickness for aesthetic reasons and to ensure consistent results in the glazing and firing processes. The outdoor display would be exposed to the elements; therefore, to weatherproof it, the clay needed to be coarse and reinforced with sandy grout. The client group lacked the dexterity required to manipulate large lumps of clay; consequently, the artist prepared over 80 rolled clay slabs. The preparation, glazing, and firing of the clay required round trips of over 140 miles by the artist, which was not only time consuming but costly. The artist was able to stay overnight in Allachburn, which was practically, financially, and logistically advantageous. These “hidden” costs can often be overlooked, and it is important to consider these in the planning stages.

6.7 Project Evaluation

Project evaluation was undertaken using a combination of qualitative and video-based observational research (VOR) through questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and video capture. The purpose of the evaluation was to determine whether the aim and objectives of the project had been met. The use of video recording was primarily aimed at producing an informal short video of the project journey for residents and their families with an iPad used by staff and the facilitator during the workshops. Although this may have provided future promotional, evidential, or educational material, there was no budget for the production of a professional film.

In this instance, there was no formal sampling method utilized due to the nature of the project; it was a convenience sample restricted to the CHF aiming to cover as many participants as possible. The participants were care home residents and their families, staff, and their children. Residents chose independently to attend, and those with dementia were involved along with the support of family members or staff.

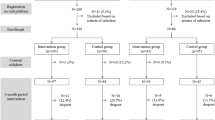

The workshops ran during school holiday time, providing opportunities for children to be involved. For those who were unable to give informed consent for participation and the evaluation, family members were involved in any decision making (see Fig. 5.1). A short questionnaire previously developed by AiH for a dementia event in 2017 was utilized, consisting of ten open and closed questions; these questionnaires were completed at the beginning and end of the workshops. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by Gil Barton with the care home manager, the AiH chief executive, and the artist (Fig. 5.2).

6.8 Results

A total of ten questionnaires were completed by eight residents and two staff members. Completion of the questionnaire by residents was challenging despite support by the facilitator and staff. Twenty residents participated throughout the workshops, although some only stayed for a short time due to their health conditions. Three residents consistently attended every session, and one of their nieces came to each morning workshop. Twelve staff members completed tiles while assisting residents, and nine children took part.

Thematic analysis of the questionnaires (Ritchie and Lewis 2011) highlighted five main themes as detailed in Fig. 5.3.

6.8.1 Theme 1: Having Fun Doing Something New

There was much fun and laughter throughout the project by both residents and staff, evident in the video footage. Some residents, while not actively participating, were content watching the workshops, and running these over two consecutive days each week for a month allowed the team to establish familiarity with residents and staff. The artist commented:

“The project really came to life with the involvement of youngsters—children of staff members or relatives of the residents—which also seemed to be the catalyst that encouraged more of the staff members to join in. This sparked a busy, positive atmosphere with a range of ages from very young to elderly engaged side by side, slightly curious about the novelty of the situation and seemingly delighted just to be having fun making something together.”

A staff participant (Respondent #8) said:

“It was SO much fun! Chatting with residents and seeing their creativity! Working with the children, at first everyone was unsure what to do but really everyone put so much in.”

6.8.2 Theme 2: Excitement

Excitement was a consistent theme throughout the responses, and it was evident that participants were interested, stimulated, and excited about undertaking something new. Having new people in the home appeared to create a different energy, which was reflected in the responses, which characterized the experience by describing it as:

“… an unusual experience” (Respondent #4)

“…general buzz” (Respondent #5)

6.8.3 Theme 3: Being Creative and Artistic

Respondents reported enjoying being creative and artistic and finding it stimulating and interesting, as illustrated by several comments:

“Belief that I can be creative, art has no barrier.” (Respondent #8)

“I did that. I’m not really an artistic person, but I did enjoy that one!” (Respondent #3)

“One of the most significant aspects of this project was the real sense of achievement in the participants when they eventually saw the dull, earthy materials they had worked with being transformed into the bright glowing display of the finished work.” (Artist)

6.8.4 Theme 4: Memory

Unsurprisingly, some of the participants were unable to recall having taken part in the creative activities without prompting. One example of this was a resident (Respondent # 6) who participated in two workshops creating a flower, stating: “I wasn’t involved.”

6.8.5 Theme 5: Impact on Health and Well-being

The responses to the question regarding impact on health and well-being were all positive, which is contrary to the preceding theme with some participants being unable to recall taking part. It could be assumed that, because most of the questionnaires were completed with the support of staff, when residents were prompted and reminded of what they created they recalled different aspects they had enjoyed. One participant (Respondent #7) highlighted this, saying: “Any activity good for your body [sic].”

6.9 Other Captured Qualitative Data

AiH believes that a professional artist working in a social rather than a medical environment is an effective approach, fitting well with the prevention agenda of public health. During an interview with the Chief Executive of AiH, she identified that having no fee was difficult however the project provided an opportunity to enable participatory activity through the workshops led by one of their artists that resulted in ‘The Tree of Many Colours’. In addition, AiH were drawn to the ‘Healthy Working Lives’ agenda that was led by Gil Barton. The commitment of all partners was essential to overcoming any difficulties, and it took creative thinking at times to achieve this.

7 Observations and Reflections

During the first workshops, the blank clay slabs were utilized; however, the artist observed that for many, the physical effort of drawing around the template and cutting the shapes was difficult. To alleviate this, in week two the artist adjusted his approach by offering participants ready-made shapes. It became apparent that not only did this increase his interaction with participants, it also enhanced the tactile experience of impressing leaves, seeds, tree bark, and other objects into the regular surface or of making patterns with clay tools, thus encouraging experimentation. The workshops, although slow, were demanding, and the artist’s reflection captures this:

“Despite the slow pace of the sessions they were deceptively intense and doing two per day was very tiring, for myself and participants. The most effective time to work seemed to be mid-morning to just before midday. Nevertheless, the later sessions were useful for accommodating the youngsters and staff that participated.”

Throughout the workshops, social interaction tended to expand into general conversation, resulting in a more relaxed and sociable atmosphere—particularly when staff dropped in to see what was happening, providing support and encouragement. When staff, relatives, and children joined in, the artist could start allocating tasks to more able participants, and the efforts of the youngsters were a source of real interest to the residents. The assembled pieces needed to dry before the application of colored stains, providing a natural break in the process and allowing for sample preparation between sessions. It was difficult for participants to envisage how the clay and colors would change as the process advanced, and this was helped by having finished glazed and fired examples available.

While there was much joy and laughter throughout the project, one resident found that taking part triggered memories that were upsetting. This female resident initially spent a happy, creative two hours during the first workshop; however, when she returned on the second day, she was despondent, lamenting about her lack of inspiration. Despite support and reassurance, she became tearful and distressed and was taken away from the workshop by staff for a cup of tea. When a family member arrived later, she was able to put this reaction into context, explaining that in the past the resident had baked beautiful wedding cakes, and this experience brought back memories as she grieved for her younger self. The resident did, however, return to a later workshop to paint her two tiles—a butterfly for the tree and a bird for her bedroom door. Recalling happy memories can enhance well-being; yet, as with this situation, reminiscing can also lead to feelings of negativity and loss (Hofer et al. 2017; Speer and Delgado 2017).

The inclusion of children brought an intergenerational aspect to the workshops and created a different dimension, and staff appeared more confident when assisting them, leading to their own creativity. Residents visibly enjoyed having the children working alongside them and sparking new conversations, which can have a positive impact on cognitive processes and creativity (Young et al. 2015). Staff reported anecdotally both during and after project completion that there was such a “buzz” about the project, and it appeared to have brought something special to Allachburn.

As described in the concluding chapter of this book, this arts-based initiative demonstrates the deep and complex interactions art stimulates within health promotion practice. Art increases connections with the self, with others and contributes to environmental beautification (see Chap. 21, this volume). Art activities can connect so viscerally with participants, it can promote profound healing, but may also produce some distress on that journey. It may be important to ensure appropriate support is in place.

7.1 Challenges and Considerations

As with any project, there were challenges—mainly funding and the logistics of working effectively as a new partnership, which can take time to develop and overcome. Fancourt (2017) identifies four main partnership models, and in this case the appointment of the artist early on was critical to the project’s progression aligning with a Collaborative Design. There were logistical challenges due to the geographical distances between the team and Allachburn, with many of these being borne by the artist, and it was his flexibility, knowledge, commitment, and passion that enabled the project to progress.

The cost of materials and the logistics associated with installing and maintaining the ceramics required specialist input that should not be underestimated. Engagement by the artist early on with the ceramic technician at the SSW led to them taking a keen interest in the project, resulting in significant ongoing in-kind support. The mounting of the individual tiles to the external wall was complex, and Allachburn’s handyman was invaluable in formulating an affordable, workable solution.

7.2 What Could Be Done Differently?

Just like any project, there are things that could have been done differently; thus, learning by the project team may be useful for others considering similar activities. The evaluation, as it stands currently, has met the project’s aim and, broadly, its objectives. Completion of the questionnaire by residents was difficult due in part to the client group, as undertaking any research and evaluation when working with dementia sufferers can be difficult (as evidenced by Chatterjee et al. 2018). The duration of the creative process was another challenging factor, with some residents forgetting they had been involved. Evaluation is something that could be done differently, particularly when considering future funding for other projects. Given the client group, evaluation methods require flexibility as highlighted by Young et al. (2015) and Fancourt (2017). The filming captured qualitative evidence of participation, emotions, and the process, which will be edited to produce a short video for residents and their families. At this stage, it is unclear whether being involved has had any impact on the health and well-being of staff. If time had allowed, a focus group with staff to explore their involvement in relation to their health and well-being would have demonstrated whether the first objective had been met. Anecdotally, the manager reported that as a result of the project, residents appeared to be more open to new ideas, and staff were more confident and eager to explore other creative activities.

8 Conclusion

The benefit of participating in the arts in relation to health and well-being across all ages and abilities is apparent, and this project’s aim—“to offer residents and staff a meaningful, stimulating and creative experience”—was clearly met. What started as an idea for a small outdoor art project grew with the collaborative approach taken by the partners and their willingness to work flexibly, regarding it as a “pilot.” This flexibility allowed the project to evolve into a significant piece of work. The inclusion of the residents’ families and staff brought a different dimension to it and engendered wider interest.

The “Tree of Many Colours” was formally opened by the Provost of Aberdeenshire, Bill Howatson, in February 2019, over a year after project discussions began (see Fig. 5.2). In addition to the ceramic “Tree of Many Colours,” a large information sign detailing the project story and credits for each tile is mounted on the front external wall of Allachburn (see Fig. 5.4). It was evident that this artistic venture had brought much happiness and joy to participants, and final thoughts from the artist highlight this:

“This was probably one of the most rewarding and enjoyable art projects I’ve been involved with. I’m very pleased that the finished work has been received so positively and my time spent in Allachburn was heart-warming and enlightening.”

Notes

- 1.

© 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

References

Aberdeenshire Council. (2016). Marr area profile. Inverurie: Aberdeenshire Council. https://www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/media/18326/marr-profile-2016.pdf. Accessed 25 Oct 2018.

Age UK. (2016). Dignity in health and social care (England). https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/policy-positions/care-and-support/ppp_dignity_in_health_and_social_care_en.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2018.

Age UK. (2017). Index of Wellbeing in Later Life. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/our-impact/policy-research/wellbeing-research/index-of-wellbeing/. Accessed 16th September 2020.

Aiden, H. (2016). Isolation and loneliness: An overview of the literature. The British Red Cross.

British Association of Art Therapists. (2018). What is art therapy? https://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy. Accessed 27 Nov 2018.

Carter, D., & Rigby, A. (2017). Turning up the volume: Unheard voices of people with dementia. In The Alzheimer’s Society. London. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/reports/turning-up-volume. Accessed 11 Nov 2018.

Chatterjee, H. J., Camic, P. M., Lockyer, B., & Thomson, L. J. M. (2018). Non-clinical community interventions: A systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts & Health, 10(2), 97–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2017.1334002. Accessed 6 Mar 2019.

Coburn, A., Vartanian, O., & Chatterjee, A. (2017). Buildings, beauty, and the brain: A neuroscience of architectural experience. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01146.

Cohen, L., Wimbush, E., Myers, F., Macdonald, W., & Frost, H. (2014). Optimising older people’s quality of life: An outcomes framework. Strategic outcomes model. NHS Health Scotland and Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research & Policy. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

Collective Encounters. (2013). Arts and dementia: Bringing professional arts practice into care settings. http://collective-encounters.org.uk/. Accessed 27 Nov 2018.

Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. (2009). Future health: Sustainable places for health and well-being. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/resources/report/sustainable-places-health-and-well-being. Accessed 12 Mar 2019.

Cutler, D. (2013). Local authorities + older people + arts = a creative combination. London: The Baring Foundation. Accessed 14 Mar 2019.

Cutler, D., Kelly, D., & Silver, S. (2011). Creative homes: How the arts can contribute to quality of life in residential care. London: The Baring Foundation.

Elkis-Abuhoff, D., & Morgan, G. (2019). Art and expressive therapies within the medical model: Clinical applications. Abingdon: Routledge.

Fancourt, D. (2017). Arts in health: Designing and researching intervention. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Green, M., Iparraguirre, J., Davidson, S., & Rossall, P. (2017). A summary of Age UK’s index of wellbeing in later life. London: Age UK. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/our-impact/policy-research/wellbeing-research/. Accessed 13 Mar 2019.

Hanratty, B., Stow, D., Collingridge Moore, D., Valtorta, N. K., & Matthews, F. (2018). Loneliness as a risk factor for care home admission in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age and Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy095.

Hofer, J., Busch, H., Poláčková Šolcová, I., & Tavel, P. (2017). When reminiscence is harmful: The relationship between self-negative reminiscence functions, need satisfaction, and depressive symptoms among elderly people from Cameroon, the Czech Republic, and Germany. Journey of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9731-3. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Holt-Lunstad, J. H., Smith, T. B., & Bradley Layton, J. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316.

Jones, R., & Yates, G. (2013). The built environment and health: An evidence review. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health. https://www.gcph.co.uk/publications/472_concepts_series_11-the_built_environment_and_health_an_evidence_review. Accessed 12 Mar 2019.

No Isolation. (2019). The state of social isolation and loneliness in the UK. https://www.noisolation.com/global/research/the-state-of-social-isolation-and-loneliness-in-the-uk/. Accessed 15 Sept 2019.

Office of National Statistics. (2017, July). Overview of the UK population. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/july2017. Accessed 20 October 2018.

Oliver, D., Foot, C., & Humphries, R. (2014). Making our health and care systems fit for an ageing population. London: The Kings Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/making-care-system-fit-ageing-population. Accessed 3 June 2020.

Owen, T. (2014). Loneliness in care homes. In Alone in the crowd: Loneliness and diversity. Campaign to End Loneliness. https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/. Accessed 14 Mar 2019.

Potter, S. (2016). Community programme social impact study evaluation report. Chichester: Pallant House Gallery.

Ritchie, L., & Lewis, J. (2011). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publications.

Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Speer, M. E., & Delgado, M. R. (2017). Reminiscing about positive memories buffers acute stress responses. Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0093. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

The Alzheimer’s Society. (2018). Facts for the media: What is dementia?. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/news-and-media/facts-media. Accessed 11 Nov 2018.

The Welsh NHS Confederation. (2018). Arts, health & well-being. https://www.nhsconfed.org/-/media/Confederation/Files/Wales-Confed/Literature-review-of-arts-and%2D%2Dhealth-and-wellbeing.pdf. Accessed 14 Sept 2019.

UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. (2017). Creative health: The arts for health and wellbeing. http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/. Accessed 9 Nov 2018.

United Nations. (2018). Ageing. http://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/ageing/. Accessed 20 Oct 2018.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2015). Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000244834. Accessed 28 May 2020.

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102, 1009–1016.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2018). The inner level: How more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone’s wellbeing. London: Penguin.

Windle, K., George, T., Porter, R., McKay, S., Culliney, M., Walker, J., et al. (2016). “Staying Well in Calderdale” programme evaluation: Final report. Lincoln: University of Lincoln.

World Health Organization. (1986). The Ottawa Charter for health promotion. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/.

World Health Organization. (2017). Dementia key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

Young, R., Camic, P. M., & Tischler, V. (2015). The impact of community-based arts and health interventions on cognition in people with dementia: A systematic literature review. Aging & Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1011080.

Zhang, Y., Tzortzopoulos, P., & Kagioglou, M. (2018). Healing built-environment effects on health outcomes: Environment-occupant-health framework. Journal of Building Research & Information. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2017.1411130. Accessed 2 March 2019.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to everyone who has helped with this project, particularly Michelle Riddock and the staff of Allachburn, Ian Robertson, Margaret O’Connor, AiH, and Beth Bidwell at SSW. Thank you to Karen Hicks, who persuaded me to submit an abstract, and thank you to my reviewers, Val Burnett and Dr. Linda McSwiggan, for their professional peer review. A final thank you goes to my husband, Professor Glenn Iason, for his reviewing, constructive comments, and endless support and encouragement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barton, G.C. (2021). Creatively Healthy: Art in a Care Home Setting in Scotland. In: Corbin, J.H., Sanmartino, M., Hennessy, E.A., Urke, H.B. (eds) Arts and Health Promotion. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56417-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56417-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-56416-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-56417-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)