Abstract

This chapter tells the story of how the Election Commission of India (ECI) became one of the most awe-inspiring electoral regulatory bodies in the world. One of the most widely celebrated and trusted public institutions in India, it has ensured the integrity—free and fair—of 17 national and more than 370 state elections since 1947, in what is not only the most populous but also one of the most potentially fractious democracies in the world. Ever under pressure from the executive branch and governing parties to bow to demands fed by their desire for electoral windfalls, the ECI managed to strengthen its autonomy through assertive leadership by a series of Chief Electoral Commissioners following the decline of the Congress Party’s political dominance. The rise of the Hindu Nationalist BJP as the new dominant force in Indian politics provides a crucial test for the endurance of the ECI’s role as India’s guardian of electoral integrity.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

From Quiescent Bureaucracy to Powerful Institution1

The Election Commission of India (ECI) is one of the most powerful electoral regulatory bodies in the world and one of the most widely celebrated and trusted public institutions in India (McMillan 2012).2 It has overseen the completion of 17 national and over 370 state elections since Indian Independence in 1947. It also conducts some of the largest and longest elections in the world. The 2019 parliamentary elections, for example, had 900 million eligible voters, and were completed in nine phases over 39 days. Celebrated as an ‘undocumented wonder’, the ECI has emerged as a guardian of public value—free and fair elections—in India (Quraishi 2014).

The role of election commissions in the regulation of elections is of vital importance throughout the world, not least because democraticlegitimacy turns on election credibility. In many countries, opposition parties protest election results and boycott elections.3 The legitimacy of election results are questioned because the institutions that ensure their validity are themselves questionable. In India, one of the most heterogeneous societies in the world, politics remains highly contentious. Both the democratic system and the state secure their legitimacy through regular free and fair elections. The ECI is responsible for India’s long-standing record of uncontested, free and fair elections.

The world over, democracy has struggled to take root in low-income countries (Przeworski et al. 2000). India’s democratic record also makes it an outlier in this respect. Elections have remained popular with the poor. Members of socially excluded groups have emerged as powerful political leaders (Varshney 2000; Jaffrelot 2003). Steps taken by the ECI have ensured that the poor and marginalized have been enthusiastic voters (Ahuja and Chhibber 2012) and have participated in elections in increasing numbers (Kumar 2009), without fear of intimidation by higher-ranked, more powerful groups. The security provided to poor voters has also enabled the rise of marginalized groups’ political parties. Leaders from these groups have achieved electoral success. Few low-income democracies can claim such transformative achievements.

The popularity of the ECI is not restricted to citizens alone; political parties have also come to view it as a neutral referee. During our interviews with 62 party leaders and officials, belonging to 15 national and regional political parties, we found that 51 of our respondents generally regarded the ECI in a positive light.4

Yet the ECI was not always as prominent or powerful, especially vis-à-vis the executive. In a parliamentary system like India’s, the cabinet and the prime minister’s office comprise the executive branch. Before 1989, the executive restricted the ECI’s autonomy. Its Chief Election Commissioners (CECs) mostly remained quiescent. Even the most entrepreneurial CECs had little leeway. Occasionally, when a CEC tried to assert his authority, like Peri Shastri in 1987, the executive would curtail his efforts.5 When innovations in electoral practice appeared, they resulted from the executive’s rather than ECI’s initiative.6

In recent decades, however, the ECI has grown into a powerful institution. Krishna Bose (2016), from the All India Trinamool Congress, remembered how the ruling Communist Party that mastered the art of rigging elections in West Bengal, had to eventually contend with ECI’s close monitoring. ‘In fact, all political parties have a vested interest in a neutral and effective EC’, she wrote. A retired Chief Election Commissioner corroborated this view during an interview: ‘Chief Ministers who do not like the EC when they are in office’, he quipped, ‘are very happy with us when they are in opposition because they rely on a free and fair poll to find their way back to power’. Baijayant Panda, from the Biju Janata Dal,7 a regional party in the state of Odisha, echoed this sentiment about the ECI’s close election monitoring: ‘It is a bit of a pain in the neck actually. But it does serve the purpose of establishing a degree of fairness and a perception of fairness’. Mayawati, India’s first Dalit (former untouchable) Chief Minister, attributed her party’s majority in the 2007 state assembly election in Uttar Pradesh to ECI protections for poor and marginalized voters.

The ECI is thus deeply implicated in India’s exceptional democratic experience. Understanding how a public institution such as the ECI was able to enhance its powers is an important question. How did the ECI build its institutional credibility? What was the role of the ECI’s leadership and strategy in the processof institution building? These are the questions that this chapter seeks to answer.

We explore and explain the ECI’s institutional development by analysing electoral data and drawing from interviews with six CECs, four Chief Election Officers and eight ECI officials. These lengthy, semi-structured interviews were conducted over two years, sometimes over multiple sittings. We also utilize insights gleaned from hundreds of voter interviews conducted across four large Indian states: Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

We use historical process-tracing to unearth the mechanisms that enabled the ECI to interpret its mandate expansively and enhance both its power and status. Such an approach allows us to identify the sequence of causes that came to produce a more powerful ECI than was originally envisioned (Goertz and Mahoney 2012). In keeping with this methodology, we carry out an over-time process analysis of ECI activities, focusing on Model Code of Conduct (‘Model Code’) implementation and election duration, considering different observations at different points in time and identifying key historical junctures and events.

We begin by describing the ECI and the executive–ECI relationship over time. We then focus on the political opportunity presented by a weakened executive, state-based demands for a referee institution and bureaucratic entrepreneurialism. We examine the ECI’s institutional challenges in a moment of executive resurgence. We conclude with reflections on the conditions that support institutional development in democracies.

The Indian Election Commission in the Time of Congress Dominance and Decline

In developing countries, public institutions rarely enjoy statutory protections from executive pressure. When they do, protections may be ignored by a marauding executive (Collier 2009).8 The ECI, over time, successfully secured institutional autonomy while expanding its mandate.

Gilmartin and Moog (2012) note that ‘in historical context, the establishment of the Election Commission can best be seen as an effort to “nationalize” elections in India, not only in structural terms to centralize their oversight, but also to associate them strongly with the idea of the Indian nation, unifying a highly disparate and divided population’. Free and fair elections require: (1) an independent electoral management body to conduct elections; (2) a set of rules governing electoral conduct; and (3) an effective electoral dispute resolution mechanism.

The Indian constitution provides all three. Article 324 establishes an independent election commission; Article 327 empowers Parliament to enact laws governing all aspects of elections; and Article 329 provides a mechanism for resolving electoral disputes through review by an independent judiciary. These articles reflect the clear preference of the Constituent Assembly to ensure the autonomy and independence of the ECI, protecting it from executive interference in particular (Devi and Mendiratta 2000).

Administratively, the ECI is tasked with a number of core electoral functions. These include the conduct of elections to parliament, all state legislatures and the offices of the President and Vice President; registration of voters and maintenance of electoral rolls; and assistance with electoral district delimitation. The ECI is headed by a CEC, who is typically an outsider drawn from senior members of the Indian Administrative Services (IAS) and the Law Commission.9 Since 1995, two additional Election Commissioners have regularly worked alongside the CEC.10

The ECI, in part, because it is small, depends upon state employees to administer elections and oversee the deployment of substantial staff. For example, 11 million personnel administered the parliamentary elections in 2019. In addition, the ECI deploys paramilitary and military forces to secure polls in insurgency-affected regions, where federal forces are often used instead of state police to guard against local influence.

While the ECI enjoys some formal autonomy from the executive, it is not an independent agency. The executive controls the EC’s finances and personnel appointments. During its first 20 years, democratic India was dominated by a single party, Congress, at both the state and national levels. Congress dominance was made possible by its stature as the face of the freedom movement, its relatively well-developed organizational structure, and the pre-eminence of its leadership. It also actively co-opted different interests.11 Congress did not intrude on ECIautonomy during this period. It did not have to, as elections regularly installed national-level Congress governments and few protested electoral irregularities (as the overall result would not change). The ECI had little reason to exercise its powers and was not pressured to do so by opposition parties.

Over time, Congress’s freedom movement leadership12 gradually disappeared, the party underwent multiple splits, and its organizational structure weakened. By 1967, Congress began losing power in the states. Under Indira Gandhi’s (‘Indira’) leadership and, later, that of her son, Rajiv Gandhi (‘Rajiv’), Congress’ hold on power became tenuous. Both leaders undermined public institutional autonomy, including that of the ECI.

During this period, the influence of the ECI was circumscribed. CECs knew that if their actions were interpreted to be detrimental to Congress’ interests, they would have to contend with Congress and the Prime Minister after the election. In describing the ECI during this period, McMillan (2010) observes that the Election Commission had become absorbed into the Congress system of government and lost sight of its broader remit to maintain the democraticstructure of the Indian political system.

The ECI’s minimalist institutional profile was reflected in the public stature of the CEC. Unlike CECs since 1991, who have been prominent public figures, pre-1991 CECs were not well-known. A remark by a CEC, who retired after 2010, captures this change:

During my tenure, I visited different states, in each place I felt the authority of the CEC’s position. The politicians and bureaucrats were deferential. I say this because this was not the case earlier. I remember being introduced to the CEC, Mr. S.L. Shakdher, in 1981, when I was serving as a district magistrate and no one knew him or really cared that much about the CEC’s office.

While discussing the same period, another CEC pointed out that ‘In those days, the ECs were just told by the PM or the Principal Secretary, get ready for elections on such and such date…. But when the elections are held is the prerogative of the CEC, not the PM’s office’. Another former CEC asserted that ‘the EC during the 1970s and 1980s was seen as a sidekick of the government…. You could find the CEC waiting outside the office of the Law Minister…. The ECI is [now] an independent and autonomous body. It does not have political masters’.

A key test of the ECI came in 1975, when the President of India, upon the advice of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, imposed Emergency Rule under Article 352 of the Indian Constitution. The justification was imminent threats to public order. During the 18-month long Emergency, Indira’s government disempowered state governments, incarcerated opposition leaders, cracked down on the press and subdued the judiciary. Then, against expectations, and for the first time in Indian history, the ruling Congress Party (‘Congress’) lost a parliamentary election. The ECI’s reputation benefited from its management of the 1977 election at the end of the National Emergency.

Overall, under Congress dominance and during its decline, CECs retained some independence despite executive power; this proved crucial in the following decades. The independence of the ECI’s office was protected during this early period for three reasons. First, it was constitutionally protected under Article 324. Second, after 1967, as Congress began to lose state-level elections, the Indira-led federal government invoked Article 356 to simply dismiss non-Congress governments, instead of resorting to rigged elections.13 The executive, therefore, had little need to override ECIautonomy. And, third, Indira’s Model Code violation and judicial disqualification in 1975 made her wary of direct institutional clashes with the ECI.14 The judiciary, by being willing to stand up to the Prime Minister’s Office, bolstered ECI authority vis-à-vis the executive. CECs we interviewed viewed the judiciary as an important safeguard. ‘The courts realize that we act in public interest’, explained one retired CEC, ‘so they have been willing to side with us and not the government’. The reputation garnered by the ECI under Congress dominance, as well as during its decline, provided opportunities for its further institutional development.

A Turning Point

In the post-Emergency period, Congress, a leader-centric party, suffered two significant organizational setbacks: the assassinations of Indira, in 1984, and her successor, Rajiv, in 1991. In the early 1990s, Congress dominance unravelled. In 1952, national-level Congress vote share was 45%. By 1967, it had shrunk to 41%, by 1991, 36% and by 2004, 27%. This decline was accompanied by: (1) an increase in the number of political parties15; (2) more competitive electoral politics; and (3) coalition governments.

With party system fragmentation in the 1990s, coalition politics became institutionalized at the national level. A similar pattern occurred in many states. Between 1989 and 2014, all 8 national governments were coalition governments. The number of states being ruled by coalition governments increased from 0 in 1952, to 4 in 1995, to 18 in 2006. In the states where regional party systems replaced Congress earlier, party systems also experienced fragmentation resulting in party proliferation. The number of state-based political parties increased from 33 in 1984 to 209 in 1996.

Before 1989, party competition was more limited. Between 1952 and 1984, the effective number of parties (‘ENP’), as measured by vote share, ranged from 3.40 to 5.19; when measured using seat-share in parliament, the range was 1.69–3.16. The corresponding ENP for the period 1989–2014 were between 4.80 and 7.98, and 3.50 and 6.50, respectively.

With no party in a position to form a majority government, a variety of coalition governments came to power. This meant that executive power was, to varying degrees, dispersed among alliance partners. The addition of multiple veto players weakened the executive.16 With coalition governance, government tenures at the national and state levels became more uncertain, surviving as long as their coalitions held. Under these constraints, political parties supported an assertive ECI that was willing to clean up the electoral process. The ECI profited from this uncertainty, as weaker governments became unlikely to limit its autonomy.17 One ECI official recounted a moment when A. B. Vajpayee’s Bharatiya Janata Party (‘BJP’)-led coalition government between 1998 and 2004 moved to appoint an outsider instead of promoting the senior Election Commissioner as CEC. When this news reached the Election Commissioners, they threatened to resign. The government withdrew its proposal (Sridharan and Vaishnav 2017).

State-based parties came into prominence during party system fragmentation. These smaller parties relied on the ECI to ensure free and fair state-level elections. As challengers, they did not trust the state machinery, bureaucrats or the police to discharge their responsibilities in a nonpartisan manner, perhaps remaining loyal to incumbents. Thus, state-based challengers turned towards the ECI, a federal body, to ensure fair state-level competition. Aware of incumbent loyalties among public officials, an assertive ECI was willing to prevent them from influencing the electoral process. Smaller parties supported ECI efforts to clean up electoral rolls, as inflated rolls allowed major parties to fraudulently exaggerate vote share. Parties also demanded the use of the federal security apparatus rather than local police during elections, which the EC was willing to support. Parties that relied on support from poor and marginalized groups supported the ECI’s vulnerability mapping project.18 The ECI cracked down on the flow of money and alcohol, despite resistance.

Occasionally, the ECI ran into resistance. In 2001, for example, the ECI had a standoff with state governments. The ECI wanted to be able to ensure public officials’ compliance with ECI instructions after state-level elections had been announced. State governments viewed this as a violation of federal principles that protect state government personnel from federal sanction. The ECI did not back down and a compromise was reached. The ECI was granted the power to remove government officials for the duration of an election, but state governments alone could act against them. The earlier changes had an immediate effect on ECI’sautonomy. Structural constraints on the ECI declined. The ECI became more autonomous and began to assert its authority.

The Pivotal Role of the Entrepreneurial Chief Election Commissioner

The collapse of single-party dominance and increase in party competition in the 1990s was a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for the development of a powerful ECI. The decline in single-party dominance weakened executive power, a key constraint on the ECI’sautonomy. Increased party competitioncreated state-based demand for the ECI’s role. These conditions provided the ECI with a political opportunity. Then, in the 1990s, entrepreneurial CECs used and built upon the credibility the ECI had developed over the years to expand its mandate in the name of serving a diverse coalition of interests.

Indeed, the CEC played an important role in the expansion of ECIpower. Mandate expansions have often been driven by entrepreneurial leadership from bureaucrats, acting in moments of political opportunity (Bakir 2009; Nay 2011). In many parts of the US federal bureaucracy, bureau and division chiefs were responsible for mandate expansion. These entrepreneurs crafted agendas, shaped the composition of the long-term, organized workforce, marketed their agencies and themselves, controlled information flowing to the legislature and, ultimately, convinced elected officials to use programs the agencies themselves had designed (Doig and Hargrove 1987; Carpenter 2001).

After 1989, with no party in a position to win a majority, the ECI faced few structural constraints on its autonomy. CECs began to assert authority over political actors during elections. The first to do so was T. N. Seshan, who introduced several changes to the election process. Seshan was able to win concessions from the Congress-led minority government to elevate the CEC’s position, in the warrant of precedence, from that of a High Court judge to that of a Supreme Court justice. He also introduced election observers for state assembly elections, pioneered voter ID cards and refused to take executive instructions. Seshan skillfully navigated an expanding media environment. He regularly issued press releases and used publicity to ‘force politicians to internalize… the norms’ embodied in the Model Code (Gilmartin 2009).

Such was his influence that politicians, it was said half-jokingly, ‘feared only God or T.N. Seshan’. His aggression and repeated executive clashes made him controversial. Sometimes he exceeded his authority and the Supreme Court stepped into overrule his decisions. Despite occasional losses, Seshan differentiated himself from predecessors by demonstrating the constitutional powers that an entrepreneurial CEC could exercise.

Seshan was the force that moved the ECI from a little-known institution to a highly regarded one in a moment of opportunity. This change was likely not inevitable and owes a considerable debt to Seshan’s leadership. Opportunities do not automatically convert into outcomes. Those of his successors who we interviewed, even those who did not always approve of his methods, acknowledged as much. A less entrepreneurial CEC may not have responded similarly to the political opportunity he received. Seshan demonstrated ECI authority and set a standard by raising the ECI’s profile and altering public expectations of both the CEC and the ECI. ‘Before Seshan, the CEC’s main job was to announce the election results’, a former CEC observed. ‘From the 1960s right up to the 80s, the ECI was being run Ram-bharose (left to the mercy of God), said another former CEC’. Additionally, another former CEC commented, ‘The ECI can continue to learn from his legacy’. One CEC described Seshan’s tenure as an era in which the CEC set new benchmarks for all CECs who followed.

The CECs who followed were not as controversial, but they were also not reluctant to assert ECI authority, even when this meant taking on the executive. More significantly, an informal norm arose in which each CEC would try to leave a mark on the ECI by improving the electoral process in some way. Introduction of electronic voting machines, vulnerability mapping, closer monitoring of elections, digitizing of voter lists, voter education programs, publishing information on a candidate’s economic assets and criminal records are all initiatives that have been introduced by Seshan’s successors.

But if the executive appoints CECs, why have weak executives not chosen more pliant CECs? After all, it is not in the executive’s interest to appoint entrepreneurial bureaucrats to the ECI, but some have done just that. Our interviews point to three answers.

First, these are seasoned bureaucrats who have spent their entire careers around politicians. An important aspect of the professionalization process is learning to mask personal preferences. It is then difficult for politicians to assess the capacity and intent of such bureaucrats. Second, potential CECs are ECI outsiders and it is only when they join the institution that they actually discover the true stature of the position. Third, bureaucrats are beholden to their profession. Their prestige is rooted in what fellow bureaucrats think of them. More than one CEC described how much their professionalreputations matter to them. One CEC noted, ‘When the ECI organizes elections, it works with civil servants from all over the country. I always felt that these bureaucrats must be able to look up to the CEC and take pride in my conduct’.

Institutional Development and Evidence of Mandate Expansion

The institutional development of the ECI occurred in two phases: a pre-1991 period, in which the ECI played an important-but-circumscribed role; and a post-1991 period, in which, the ECI, under a weakened executive and led by an entrepreneurial CEC, began to expansively interpret its constitutional mandate and play an increasingly powerful role. Below we substantiate the ECI’s expanded role by examining two key indicators: Model Code Implementation and Election Duration.19 We use these two indicators because: (1) they represent the most significant manifestations of the ECI’s expansively interpreted mandate and (2) they can be tracked longitudinally.

Model Code Implementation

The Model Code of Conduct began in the South Indian state of Kerala, in 1960, as a consensus between political parties regarding their electoral conduct. It delineates the types of appeals that may be made during the run-up to an election (e.g. no ethnic or religious appeals, no criticism of candidates’ private lives), outlines the procedures that must be followed for meetings and processions, describes what members of the ruling party cannot do while acting in official capacity, describes permissible election manifesto material and lists polling day rules (e.g. distance parties must maintain from polling booths, how parties must cooperate with authorities, how party workers must identify themselves, etc.). While infractions occur on a regular basis, parties largely adjust their conduct once officially notified, suggesting that the Model Code does represent the rules of the game.20

Until the late 1980s, the ECI merely watched how the Model Code was updated and gradually adopted by additional states. It wasn’t until 1990, however, that the ECI enforced it. In December 1990, T. N. Seshan became CEC and quickly began pursuing ECI independence and mandate expansion. He did so, in part, by formalizing the Model Code. These efforts drew the ire of Narasimha Rao’s Congress government and the executive pushed back, expanding the ECI to three members to check Seshan’spower. These two additional election commissioners failed, however, to curtail both the ECI’s power expansion and Model Code institutionalization.

As Singh (2012: 153) explains, ‘since 1991, the Model Code has come to be seen as an integral part of elections, making the electoral contest democratic by ensuring that the party in power and those who staked claims to power would abide by certain rules, and by pruning the powers of the ruling party to reduce the advantage that it may have in the electoral arena’. One former CEC pointed out, ‘[we] are interested in catching violations of the Model Code. It requires substantial manpower. But in such a competitive environment rivals (parties and candidates) monitor each other. A large number of complaints and Model Code violation reports come from political parties. We take these complaints very seriously and investigate them immediately’. ECI officials knew that a proliferation of television channels and media platforms ensure that such incidents are well-publicized, so the ECI has to respond swiftly.

Examples of Model Code enforcement abound. In January 2017, Arvind Kejriwal was censured for remarks at a rally in Goa.21 Kejriwal, the Aam Admi Party leader, suggested that voters, when parties offer Rs. 5000 for their vote, should ask for Rs. 10,000. In 2015, in the lead-up to Bihar’s state elections, BJP President Amit Shah was censured for stating that, if the BJP loses in Bihar, ‘firecrackers will go off in Pakistan’, a violation of the provision prohibiting aggravation of existing differences or creation of mutual hatred. In the same election Rahul Gandhi, Congress Vice President, was cautioned for suggesting that the BJP makes Hindus and Muslims hate each other; these were unverified allegations used to criticize other candidates or their workers. A more subtle Model Code violation occurred in the lead-up to the 2009 general elections. The ECI notified the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, the Cabinet Secretary and the Chief Secretary of Delhi, for taking out a full-page advertisement on the 2010 Commonwealth Games in major Delhi newspapers listing the infrastructure built for the event and the thousands of job opportunitiescreated. The ECI found this list of the government’s achievements to be a clear Model Code violation.

Since it is not based on legislation passed in parliament, the Code is not judicially enforceable. The action against a violator usually takes the form of an advice, warning or censure. No punitive action can be taken. But this does not make the Code toothless. Its moral authority outweighs its legal sanctity. Its impact is instant. Political leaders are scared of inviting a notice for a violation, as it creates negative public perception about them and their party just before elections. Importantly, while individuals sometimes contest whether their behaviour truly violated Model Code regulations, both candidates and parties almost never argue that the Model Code is illegitimate or should be abandoned.

Election Duration

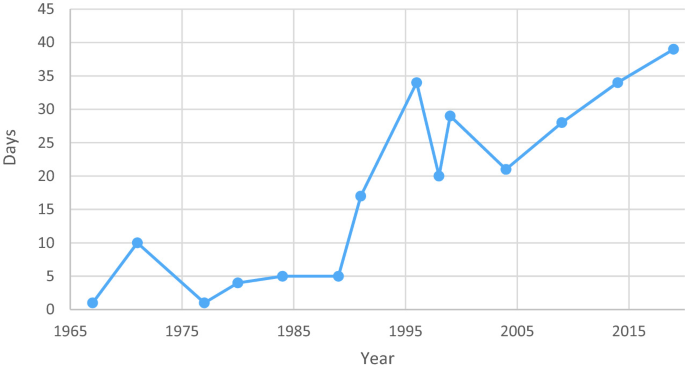

In addition to Model Code institutionalization, the ECI’s expanded mandate manifested itself in the duration of both national (parliamentary) and state-level elections. With the exception of the 1952 and 1957 national elections, early Indian elections, as evidenced by Fig. 2.1, were brief. Most national elections, from independence to 1996, took only a few days. This has since changed dramatically. The first three parliamentary elections were held over four months, 17 days and ten days, respectively.22 The three elections conducted between 1967 and 1977 were each completed in less than seven days. The same trend continued through the 1980s. The 1991 election was supposed to be completed in a week; however, Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in the middle of the election extended its duration.

Since 1991, however, the general trend has been towards substantially longer elections. In 1996, election duration began to increase sharply. The 1996 election was completed in three phases over the course of a month; the 1998 election in four phases over three weeks; the 1999 election in five phases over four weeks; the 2004 election in four phases over three weeks; the 2009 election in five phases over four weeks; and the 2014 and 2019 elections in nine phases over five weeks.

This pattern holds at the state level as well, where the ECI also conducts elections. While longer election duration is particularly pronounced in larger states, it also exists in smaller states. For example, in Bihar, the average pre-1991 election duration was 1.4 days, and 17 days since then. In Maharashtra, the average pre-1991 election duration was 1.86 days, and 8.75 days since then. Meanwhile, in Odisha, the pre-1991 number is 3, and 6 since then. In Andhra Pradesh, pre-1991 election duration averaged 1 day, while post-1991 duration averaged 8 days. Finally, in Assam, a much smaller state, in terms of both geographic size and population, average pre-1991 election duration was 1.75, while post-1991 duration was 3.8.

Entrepreneurial CECs justified the increase in election duration by pointing to demands for cleaner elections. The ECI has to move security force personnel and other parts of the administrative apparatus over long distances. These logistical constraints help justify longer election duration because they are directly related to the process of ensuring free and fair polling.

The ECI’s expanding mandate in the post-1991 period is also visible across other indicators. Since 1991, the ECI has mandated voter ID cards, curtailed campaign periods, engaged in large-scale voter mobilization, tried to regulate political parties and entry of candidates into the electoral process, and assumed both executive and quasi-judicial control during elections (Quraishi 2014).

Credibility: The EC’s Core Institutional Currency

The ECI has gradually expanded its mandate and increased its activity both during and in the run-up to elections. The enforcement of the Model Code, curtailment of electoral campaigns and longer election durations all constitute mandate expansion. While some credibility was required in order to make these changes, they have also served to reinforce institutional credibility, which has, in turn, allowed the ECI to leverage public and sometimes judicial support to confront government’s intrusion between 1990 and 2014. It has helped the ECI to become a powerful public institution. A closer look at the ECI’s pursuit of credibility reveals how important this ratchet function was to the ECI’s expansive interpretation of its mandate.

The ECI entered the era of party system fragmentation in the 1990s with some institutional credibility. Its quiescence during Indira Gandhi’s and Rajiv Gandhi’s tenures notwithstanding, it had retained a degree of independence, and it had successfully conducted a large number of national and state assembly elections. Since 1967, Congress had regularly lost power to opposition parties in state assembly elections overseen by the ECI.

The 1977 and 1989 national elections were pivotal to the ECI’scredibility. Opposition leaders had feared that post-Emergency elections in 1977 would be rigged in Congress’ favour. Charan Singh wrote as much to Jayaprakash Narayan (both opposition stalwarts) in January 1977: ‘Mrs. Gandhi is thinking of staging an election. I call it “staging” because conditions for a real election–free and fair–will be lacking’ (Raghavan 2017). As it turned out, Congress was voted out of national office for the first time during these elections. Had the ECI not presided over a free and fair election in 1977, political parties would likely have had less faith in the ECI as an honest referee and would have resisted its mandate expansion.

Prior credibility allowed an ECI led by an entrepreneurial CEC to take advantage of a political opportunity and expand its mandate. The ECI then used its added powers to further equalize treatment: demonstrating political neutrality and being willing to intervene in favour of marginalized voters. This approach reinforced the ECI’s credibility.

The long-term credibility of a referee institution turns on its perceived neutrality. The EC needs to be viewed as an impartial institution by two sets of actors: (1) politicians and political parties and (2) voters. The ECI has put in place a set of policies to ensure neutrality with respect to both sets.

To ensure neutrality with respect to politicians and political parties, the ECI appoints a Chief Election Officer for each state who reports directly to the ECI. It also has the power to remove and/or suspend partisan state government officials. To secure polling stations and voting machines, the ECI always uses the Central Armed Police Forces to ensure that any security action taken is not affected by local-level loyalties. It also penalizes candidates for Model Code violations. Finally, it regularly consults with political parties, especially before implementing new policies, and takes their concerns into consideration. In the words of an ECI official, ‘elections are their show, we are only referees’.

To ensure neutrality with respect to voters, particularly subnationalist groups and individuals especially suspicious of the ruling dispensations in Delhi or their respective state capitals, the ECI has ramped up security in violence-prone areas and conducted vulnerability mapping. The ECI’s past failure on this count proved consequential. During the 1987 state assembly elections in Jammu and Kashmir, when, under the federal government’s pressure, the ECI looked the other way while the elections were rigged in favour of state-backed parties, it triggered an insurgency. The ECI’s failure contributed to the onset of India’s bloodiest internal conflict, but also provided the ECI with a learning opportunity.

A more assertive ECI has been able to ensure that elections in violence-prone areas are seen as free and fair. For example, J. M. Lyngdoh, CEC in 2003, spoke to the Army and Paramilitary commanders in Jammu and Kashmir and told them that security forces should neither cast ballots nor force citizens to vote to boost turnout, as doing so would rob the election of its legitimacy (Lyngdoh 2004). He also threatened to cancel the election results if his warnings were not heeded.23

Similarly, as CEC, M. S. Gill engineered a compromise to enable free and fair elections in Assam, in 2001. Gill assured local groups that they could petition the ECI to cancel the votes of Bangladeshi migrants whose Indian citizenship was in doubt, thus preventing a boycott of the elections by local ethnic groups. Along the same lines, soon after the 2002 Hindu–Muslim violence in Gujarat, the ruling BJP called an election that would allow it to benefit from religious polarization.24 The ECI thwarted this plan, challenging the state government’s assertion that the state was ready to hold a free and fair election (Lyngdoh2004), and delaying the elections by six months.

Besides deploying security forces and delaying elections after violent incidents, the ECI closely tracks criminals and potential troublemakers. Preventative arrests are made, surety bonds are obtained and targeted individuals are tracked with video surveillance. Candidates with criminal backgrounds are continuously tracked. Reports of observers, security personnel, media and videographers are reviewed to assess instances of violence (Shukla 2010; Mendiratta 2010). If they suggest disruptive activity, then a re-poll is ordered immediately. These efforts seem to have paid off, as instances of electoral violence have dropped dramatically across most states. During the 1970s and 1980s, electoral violence claimed hundreds of lives and polling booth-level irregularities were common across some states (Crossette 1989). This is no longer the case.

The ‘active neutrality’ described above also characterizes ECI vulnerability mapping efforts to ensure the equal opportunity of voters who are particularly susceptible to social intimidation and disenfranchisement. In North Indian states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, where historically marginalized voters have been intimidated and prevented from voting, acts of violence and bullying have dropped drastically. During interviews, elderly Dalit voters in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar often reported that in the past they had been asked not to vote, or turned away from polling stations after being told by dominant caste individuals that their ballots had already been cast. One-on-one interviews revealed that 33% of 206 Dalit subjects in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar reported that either they or a member of their immediate family had experienced intimidation during elections at some point (Ahuja 2019).25 Today, the situation is different, however. During recent interviews, voters rarely reported feeling insecure or unsafe while lining up to vote on the day of polling.

Post-1991, the ECI came to be regarded as a force for good in Indian politics and neutrality was essential to its success. CECs we interviewed generally believed that being perceived to be above partisan and ethnic politics was critical to their credibility with both parties and the public. An increase in political contestation beginning in 1967 tested the ECI’s role as a referee institution. The ECI is a public facing institution, so its legitimacy in the eyes of the citizens and political actors turns on its performance. Elections are high-stakes contest, especially in first-past-post winner-take-all electoral systems like the one in India. The widespread acceptance of election results across the political spectrum of India’s multiparty democracy as well as the reduction in electoral irregularities and violence together have built the ECI’slegitimacy.

Return to Quiescence?

Since 2014, after a gap of twenty-six years, the executive has been resurgent in India. All governments between 1989 and 2014 were coalition governments and no single party enjoyed a parliamentary majority. The Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) attained parliamentary majorities in both 2014 and 2019. Its vote share increased from 31% in 2014 to 38% in 2019. The BJP is also in government in a majority of Indian states. For the 2019 elections, the ENP values, based on both vote and seat shares, have fallen to 5.4 and 3.0, respectively.

It should not be surprising, then, that the executive has instead turned to the tactic of limiting the ECI’sauthority from within, by appointing pliant election commissioners. The ECI deferred the 2017 Gujarat state assembly elections. This move went against the ECI’s own convention and opposition parties alleged that the ECI’s actions were designed to delay the implementation of the Model Code of Conduct and allow the BJP-led Gujarat government to announce new programs that might convince voters to cast their ballots for the BJP. In a separate incident, the CEC disqualified twenty legislators of the Aam Admi Party, a BJP rival, from the Delhi assembly. As this move occurred without following due process, the CEC was criticized for his actions. The ECI was also widely criticized for its meek response to Narendra Modi and the BJP’s repeated model code violations during the 2019 parliamentary election campaign. The ECI was slow to respond to these violations, and it failed to censure bad behaviour and impose penalties on the ruling party and the prime minister.

By contrast, it was much swifter in its response to similar violations by opposition parties. The same pattern was visible in the 2020 Delhi state assembly elections. Faced with unprecedented levels of hate speech, the ECI’s rebuke was weak at best.26 Together, these actions point to a consequential slide. The ECI’s moves in the state assembly and the 2019 parliamentary elections have cast a shadow over the ECI’s reputation for neutrality, something it has gradually built over decades.

Still, election commissioners are not as helpless in the face of a marauding executive as they were in the 1980s. Today, entrepreneurial election commissioners can leverage the ECI’s enhanced reputation to retain its authority and stand up to the executive. One of the Election Commissioners, Ashok Lavasa, wrote four dissenting notes against the ECI’s meek response to the Model Code violations of the BJP and its leadership during the 2019 elections. After taking office, the BJP government was swift to punish Lavasa by opening investigations against his family. Lavasa is scheduled to take over as India’s next CEC in 2021. It remains to be seen if the executive will intervene to prevent this transition.

To assert its authority, the ECI can also draw on the demand for a reputable referee institution among India’s national and numerous regional political parties. It risks politicization of the institution, however, if it relies solely on support from opposition parties to stand up to the executive. In addition, ultimately, if the election commissioners and the chief election commissioner in particular, are unwilling to protect the ECI’s institutional autonomy from the executive who appointed them, the ECI will struggle to maintain its power and reputation. To the degree that the executive wins this battle, we expect weaker Model Code implementation and the emergence of irregularities that favour the executive.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we showed that the Indian EC’s mandate expanded during a moment of political opportunitycreated by a fragmented party system. Faced with a weakened executive and a more competitive party system between 1989 and 2014, and led by entrepreneurial bureaucrats, the ECI successfully bargained for greater political power. The institutional values of competence and integrity enhanced the ECI’s credibility. It gradually increased its credibility by offering additional protections to voters and procedural assurances of the fairness of the voting process. As it did so, it began to enforce a Model Code and expanded the scale and duration of the electoral process. Political parties that had become increasingly reliant on a strong, neutral referee institution were unable to resist the ECI’s expansionist interpretation of its mandate.

The ECI emerged as a credible referee institution, not only for India, but as a model for the developing world, where contested election results and biased referee institutions have often weakened the foundations of democracy. This chapter suggests that a weak executive, often associated with political uncertainty and therefore regarded as detrimental to state institutions, can benefit credible regulatory institutions led by bureaucratic entrepreneurs and be a boon for state capacity in the long run.

The ECI is not invincible, however. Since 2014, the resurgent executive has constrained the ECI, and if the ECI’s competence is in question, or its behaviour is perceived as being partial it will also begin to lose its legitimacy. In fact, as recent democratic experience has highlighted and the literature on democratic backsliding has documented, neutrality of referee institutions and the credibility of the democraticprocess cannot be taken for granted, even in long-standing democracies (Levitsky and Ziblat 2018). Such institutions are vulnerable to being undermined from the outside as well as from within.27

One clear implication of this chapter on the ECI’s institutional development is that a weak executive can facilitate the strengthening of state institutions. A competitive party system that regularly transfers power from one party or coalition to another allows state institutions the space to both remain apolitical and maintain high credibility. Such a party system also creates a demand for neutral institutions. A single-party or a single-coalition dominant system is likely to have the opposite effect. In a single-party system, institutional mandates and credibility are protected by strong leadership or executive self-restraint. In India, while a CEC enjoys substantial protections, their appointment is in the hands of the executive making the ECI vulnerable.

The corollary of this argument is that a stronger executive may well reassert itself and reclaim the authority it has ceded to the ECI over the years. We do observe evidence that points in this direction. Still, given the credibility the ECI has accumulated, even a strong executive must avoid an open challenge to the ECI’s institutional authority. Demands for referee institutions are unlikely under single-party dominance; instead they appear in moments of political contestation. In federal systems, state-based actors often demand strong referees. Governance of heterogeneous, pluralistic polities demands a set of shared institutions, principles and procedures that make it possible to rule a divided society without undue violence. Such rules are particularly necessary in federal systems where power is shared between the federal and provincial governments. In such systems, citizens and state-based political organizations may want common rules and external referees, even as they remain opposed to central rule. Generally, we expect that the greater the number of conflicts at the subnational level, the higher the demand for federal referee institutions.

The findings of this chapter can be connected to perennial questions about public institutions. When are institutions able to expand their mandate and accumulate power in the name of public welfare? How are institutions able to take advantage of political opportunities to preserve and expand their power? Broadly speaking, the evidence points to a nested set of factors at work in a federal democracy: the political opportunity presented by weakened institutional constraints is a necessary prerequisite for institutional mandate expansion. In this moment of opportunity, when entrepreneurial bureaucratic actors take advantage of a demand for a competent, neutral arbiter, they are able to successfully increase the powers of their institutions.

Questions for Discussion

-

1.

This chapter describes two types of institutional leadership. Can you identify both types and explain how they relate to the institutionalization of the ECI?

-

2.

What roles do national election regulators such as the ECI play within the political process, and what values do they seek to safeguard?

-

3.

What are the main challenges to the effectiveness and legitimacy of national election regulators?

-

4.

How did the ECI manage to overcome these challenges—what were the key drivers of its current status as a public institution?

-

5.

How might the independence and competence of regulatory bodies such as ECI be ensured irrespective of who holds political power at any given time?

Notes

-

1.

This chapter draws substantially on previously published work: Ahuja and Ostermann (2018).

-

2.

The 1996 National Election Study (‘NES’) found that the ECI enjoyed the highest level of public trust among major public institutions, including the judiciary, police and political parties (Mitra and Singh 1999). In the 2004 NES, 80% of respondents believed elections to be free and fair (De Souza et al. 2008).

-

3.

Beaulieu (2014) examines 1975–2006 electoral protest data and finds that after 1990 post-election protests increased threefold and election boycotts ninefold.

-

4.

Interviews conducted by Ahuja between 2004 and 2009 in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

-

5.

Peri Shastri annoyed Rajiv’s government by not adhering to the government’s election schedule. Unable to fire Shastri, the executive punished him by opening false investigations against him and packing the ECI with two additional Election Commissioners.

-

6.

For example, in 1971, Indira shifted vote-counting from polling stations to district headquarters. Indira, who was popular among poor voters, believed them vulnerable to reprisals from property-holding groups and acted to protect their anonymity (Blair 1972).

-

7.

Baijayant Panda shifted from Biju Janata Dal to Bharatiya Janata Party in March 2019.

-

8.

In postcolonial democratic societies, universal franchise from the beginning presented an institution-buildingchallenge (Nordlinger 1968).

-

9.

Most CECs have been IAS officers. This is not surprising—conducting elections is an administrative exercise carried out with the help of state-level bureaucrats.

-

10.

In 1989, a Congress-led government appointed two additional Election Commissioners for the first time. This policy was reversed soon after. The number of Election Commissioners increased again in 1993. After a legal challenge in 1995, the Supreme Court approved two additional Election Commissioners permanently.

-

11.

These included ethnic, religious and class-based interests. Congress was a catchall party.

-

12.

By ‘freedom movement leadership’ we me those members of the Congress political party who were actively involved in the struggle to free India of British rule, including Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel and Rajendra Prasad.

-

13.

Article 356 was invoked only thrice from 1949 to 1974, while from 1975 to 1979, it was invoked 21 times, and, from 1980 to 1987, 18 times.

-

14.

The complaint against Indira was made not to the ECI, but the courts, which found in the complainant’s favour.

-

15.

The logic of federalism implies that coalition governance at the national and state levels creates more opportunities for small parties to gain access to public resources.

-

16.

According to Tsebelis (2002), veto players are individual or collective actors who possess the power to prevent a decision-outcome.

-

17.

Rudolph and Rudolph (2001) suggest that in a moment of executive weakness the Indian state shifted from interventionist to regulatory mode. This may not entirely be true. For instance, the executive mustered the coalition strength to extend affirmative action programs to Other Backward Castes in 2006 and implemented a national rural employment guarantee program across India in 2008. Since all parties desired a neutral referee, it was not possible for the executive to build a similar coalition against the ECI.

-

18.

Vulnerability mapping involves the ECI identifying groups—like the poor, Dalits and Scheduled Tribes—that are particularly susceptible to voter intimidation. At relevant polling stations, the ECI then contacts these individuals to assure them of ECI protection on the day of the election. Vulnerable voters are encouraged to report misconduct and immediate action is taken on complaints.

-

19.

We measure election duration from first to last polling date after removing exceptional dates. We do not use election notification or MCC enforcement date because of the longitudinal nature of our analysis; the level of disruption associated with the first has changed over time and the second did not exist during many of the early years included in our analysis, thus preventing clean comparisons.

-

20.

The exception is with respect to alcohol distribution during the campaign. The Model Code prohibits this and the distribution of similar enticements, but, despite the ECI generally confiscating thousands of litres of alcohol during an election, most parties at least attempt to continue this practice.

-

21.

Censure is supposed to publically embarrass the candidate in the middle of an election campaign. When appropriate, the ECI can file a criminal complaint against the candidate.

-

22.

Poor infrastructure, weather and lack of experience conducting elections contributed to the unusual length of these first elections.

-

23.

We learned this from ECI officials we interviewed.

-

24.

The BJP and the state government were directly implicated in supporting an anti-Muslim pogrom.

-

25.

These semi-structured interviews were conducted in 2004 across rural and urban Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The subjects for these interviews were selected using stratified random sampling.

-

26.

The ECI’s conduct during the 2020 Delhi state assembly election provoked criticism from one of the former CECs (Quraishi 2020).

-

27.

For a similar argument about European bureaucracies, see Olsen (2007).

References

Ahuja, A. (2019). Mobilizing the Marginalized: Ethnic Parties without Ethnic Movements. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ahuja, A., & Chhibber, P. (2012). Why the poor vote in India: “If I don’t vote, I am dead to the state”. Studies in Comparative International Development,47(4), 389–410.

Ahuja, A., & Ostermann, S. (2018). From quiescent bureaucracy to undocumented wonder: Explaining the Indian Election Commission’s expanding mandate. Governance,31(4), 759–776.

Bakir, A. (2009). Eclectica, June 2009. Kidney,18(4), 172–174.

Beaulieu, E. (2014). Electoral Protest and Democracy in the Developing World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blair, H. (1972). Ethnicity and democratic politics in India: Caste as a differential mobilizer in Bihar. Comparative Politics,5(1), 107–127.

Bose, K. (2016). A little bit of faith. The Indian Express, May 24. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/editorials/election-commission-of-india-campaign-financing-elections-india-2815835/. Accessed 11 March 2020.

Carpenter, D. P. (2001). The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862–1928. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Collier, P. (2009). Wars, Guns, and Votes: Democracy in Dangerous Places. London: Random House.

Crossette, B. (1989). Wounded India candidate is reported near death. The New York Times, November 24, Section A, p. 14.

De Souza, P. R., Palshikar, S., & Yadav, Y. (2008). State of democracy in South Asia: India. In H. Sethi (Ed.), State of Democracy in South Asia: A Report (pp. 35–61). New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Devi, V. S. R., & Mendiratta, S. K. (2000). How India Votes: Election Laws, Practice and Procedure. Delhi: Butterworths.

Doig, J. W., & Hargrove, E. C. (Eds.). (1987). Leadership and innovation: A biographical perspective on entrepreneurs in government. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gilmartin, D. (2009). One day’s Sultan: T.N. Seshan and Indian Democracy. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 43(2), 247–284.

Gilmartin, D., & Moog, R. (2012). Introduction to “Election Law in India”. Election Law Journal,11(2), 136–148.

Goertz, G., & Mahoney, J. (2012). A Tale of Two Cultures: Qualitative and Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jaffrelot, C. (2003). India’s Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in North India. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kumar, S. (2009). Patterns of political participation: Trends and perspective. Economic & Political Weekly,44(39), 47–51.

Levitsky, S., & Ziblat, D. (2018). How Democracies Die. New York: Broadway Books.

Lyngdoh, J. M. (2004). Chronicle of an Impossible Election: The Election Commission and the 2002 Jammu and Kashmir Assembly Elections. Delhi: Viking.

McMillan, A. (2010). The election commission. In N. G. Jayal & P. B. Mehta (Eds.), The Oxford Companion to Politics in India (pp. 98–115). Delhi: Oxford University Press.

McMillan, A. (2012). The election commission of India and the regulation and administration of electoral politics. Election Law Journal,11(2), 187–201.

Mendiratta, S. K. (2010, November 15). Interview by Michael Scharff. Innovations for successful societies. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/interviews/sk-mendiratta. Accessed 11 March 2020.

Mitra, S., & Singh, V. B. (1999). Democracy and Social Change in India: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the National Electorate. New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Nay, O. (2011). What drives reforms in international organizations? Governance,24(4), 689–712.

Nordlinger, E. (1968). Political development: Time sequences and rates of change. World Politics,20(3), 494–520.

Olsen, J. (2007). Europe in Search of Political Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Panda, B. J. (2010, November 19). Interview by Rushda Majeed. Innovations for successful societies. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/interviews/shri-baijayant-jay-panda. Accessed 11 March 2020.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, R. M., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quraishi, S. Y. (2014). An Undocumented Wonder: The Great Indian Election. Delhi: Rainlight.

Quraishi, S. Y. (2020). A weak rebuke: It’s unfortunate EC didn’t punish hate speech in Delhi campaign. The Indian Express, February 8. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/a-weak-rebuke-delhi-assembly-elections-ec-notice-campaigning-6256658/. Accessed 11 March 2020.

Raghavan, S. (2017). How emergency provided the template for the mobilisation of Hindutva forces. Hindustan Times, March 29. https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/how-emergency-provided-the-template-for-the-mobilisation-of-hindutva-forces/story-Uclk7ARJf7CCdq7Fu19lSK.html. Accessed 11 March 2020.

Rudolph, L., & Rudolph, S. (2001). Redoing the constitutional design: From an interventionist to a regulatory state. In A. Kohli (Ed.), The Success of India’s Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shukla, A. (2010, November 18). Interview by Michael Scharff. Innovations for successful societies. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/interviews/alok-shukla. Accessed 11 March 2020.

Singh, U. (2012). Between moral force and supplementary legality: A Model Code of Conduct and the Election Commission of India. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy,11(2), 149–169.

Sridharan, E., & Vaishnav, M. (2017). Election Commission of India. In D. Kapur, P. B. Mehta, & M. Vaishnav (Eds.), Rethinking Public Institutions in India. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

Tsebelis, G. (2002). Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Varshney, A. (2000). Is India becoming more democratic? The Journal of Asian Studies,59(1), 3–25.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ahuja, A., Ostermann, S. (2021). The Election Commission of India: Guardian of Democracy. In: Boin, A., Fahy, L.A., ‘t Hart, P. (eds) Guardians of Public Value. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51701-4_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51701-4_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-51700-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-51701-4

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)