Abstract

This chapter focuses on the development of sustainable business models for innovation in the Swedish agri-sector. This is important for several reasons. Many of society’s challenges are linked to social, environmental and economic aspects of agriculture, and numerous agri-companies have been reduced to subcontractors with little influence, and are struggling with low profitability.

Previous research regarding agri-companies have mainly focused on production and cost-efficiency aspects. Research regarding sustainable innovation and sustainable business models in the agri-sector is limited to date. To fill in this gap, the aim of this chapter is to illustrate and analyse how Swedish agri-companies develop sustainable business models. An integrated theoretical framework combining research regarding sustainability-oriented innovation and sustainable business model archetypes has been developed in order to collect and analyse the eight agri-companies in the study.

Swedish agri-companies focus not only on optimization but also on their organizational transformation and systems building when developing sustainable innovation. They have developed diversified business models. A common, important factor is to adopt stewardship roles. Further, the value intention of agri-entrepreneurs is a relevant factor when developing sustainable business models.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Sustainability-oriented innovation

- Business model archetypes

- Agri-company

- Stewardship

- Societal challenges

- Value creation

- Customers

- Value intention

5.1 Introduction

This chapter focuses on the development of sustainable business models for innovation in the Swedish agri-sector. This is important for several reasons. At the global level, many of society’s challenges are linked to social, environmental and economic aspects of agriculture. Worldwide food production must increase by 70% from 2009 to 2050, and in developing countries, the increase needs to be 100% (FAO 2011). However, productivity growth has fallen and remains below potential in many countries (OECD 2019). Simultaneously, the negative climate impact of agriculture has to be reduced. The recently released IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Land highlights the interconnection between climate change and the agri-sector (including forestry). At the same time, as some parts of the agri-sector are drivers of climate change, sustainable agriculture and forestry can reduce climate change (IPCC 2019). Further, research has suggested that investment in agriculture is an effective strategy to achieve many of society’s development goals, like poverty and hunger, nutrition and health, education, economic and social growth, peace and security and preserving the world’s environment (Dobermann and Nelson 2013).

The IPCC report also states that climate change represents a threat to the agri-sector (IPCC 2019). As research has identified, there is a need to focus R&D on how to improve agricultural adaptation to climate change, especially in food-insecure human populations (e.g. Lobell et al. 2008). Furthermore, sustainable food production will have to address aspects such as the nutritional quality of diets and positive health effects (Benbrook et al. 2013; Średnicka-Tober et al. 2016).

Agricultural research has made important contributions to poverty reduction and food security over the last 40 years (Thornton et al. 2017). Research has also identified investment in R&D as an important driver of growth in agricultural production efficiency (Alston 2010, 2018; Fuglie et al. 2017). Regardless, European Union’s Research and Innovation Programme “Horizon 2020” (European Commission 2011) and United Nations’ “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” including the 17 sustainable development goals (SDG) (Griggs et al. 2013; United Nations 2015; European Commission 2016) call attention to the need for more research and innovation on food security and sustainable agriculture.

At the firm level, many agri-companies often struggle with low profitability. In order to be able to produce, distribute and sell more food, they need to achieve profit goals. The majority of agri-companies have focused on their role as producer at the beginning of the food value chain and, consequently, have focused on becoming more effective and being able to produce more with the same, or less, resources. However, the issue of profitability remains an issue for agri-companies (Dobermann and Nelson 2013; Ulvenblad et al. 2016), and they face increasing demands from governments, local authorities, other companies in the agri-value chain and end customers regarding quality and sustainability issues.

The focus on efficiency, economies of scale and growth has been an effective approach for the agri-sector (Alston 2018). Over time, many of the small cooperatives and networking firms in the agri-sector have either joined or become large multinational companies through mergers and acquisitions. Though this trend has led to cost-effective production and distribution systems, has it also built barriers for sustainable business model innovation in the agri-value chain?

In recent times, small agri-companies have often been reduced to a subcontractor role without any real influence (Ulvenblad et al. 2016). It is known that power asymmetry combined with low-quality business relationships can lead to suboptimization and a reduced ability to identify and meet end-consumer needs (Benton and Maloni 2005; Schulze-Ehlers et al. 2014). Large companies mainly look for standardized products that suppliers produced at low cost, and innovations developed by smaller companies along the food chain making products better but different can be difficult to integrate into big companies’ business plans and delivery systems.

These are important issues, because of the increased worldwide competition, advanced technological developments and large-scale production existing in the agri-sector, and with a resulting general trend towards fewer and larger farms (OECD 2016), it remains to be seen whether the global goals of sustainable agricultural development can be met.

The agri-sector is different from other industries for several reasons: food from living things, animals and plants, must meet specific welfare, health and safety requirements. Furthermore, production and often distribution are generally connected to a specific geographic area, where nature and climate may have important influence and establish constraints to production and distribution. OECD (2019) highlights the need for more responsive agricultural innovation systems, since climate change and weather-related production shocks are expected to increase the challenge of improving productivity, sustainability and resilience on farms.

When increasing productivity, efficiency and economies of scale have become very important in the agri-sector, small- and medium-sized agri-companies engaged in business model innovation focusing on sustainability must take a more strategic and innovative perspective. A strategy for these companies can be to expand their business not through traditional growth, but rather by diversifying activities and focusing on cooperation. Research have shown that small- and medium-sized agri-companies that have been able to overcome the challenges of the agri-sector have developed sustainable business models based on a diversified approach (Ulvenblad et al. 2016), a network approach (Lawson et al. 2008) or a value-net approach (Kähkönen 2012). These sustainable business models often generate value not only for customers but also for other stakeholders, the community and the environment (Barnett and Salomon 2012; Kiron et al. 2013; Schaltegger et al. 2016).

Previous research regarding agri-companies have, in general terms, focused on production and cost-efficiency (Alston 2010, 2018). Further, research regarding business models has often addressed industries other than the agri-sector (Tell et al. 2016) such as media, information technology and biotechnology industries (Johnson 2010).

Schaltegger et al. (2016) state that “The business model perspective is particularly interesting in the context of sustainability because it highlights the value creation logic of an organization and its effects and potentially allows (and calls) for new governance forms such as cooperatives, public private partnerships, or social businesses, thus helping transcend narrow for-profit and profit-maximizing models” (p.5). This is line with Boons et al. (2013), who conclude that business models are useful for the creation and study of sustainable innovation. Lambert and Davidson (2013) and Zott et al. (2011) have shown that a sustainable business model is a useful tool when studying how a single company or an entire value network achieves sustainability in terms of environmental, social as well as economic value. However, the existing research on sustainable business models in the agri-sector has often been limited to and addresses developing rather than developed countries (e.g. the United States and European countries) (Beuchelt and Zeller 2012). Even though a structured literature review reveals an increasing number of research articles that examine sustainable business model innovation in the agri-sector, there is a need for more research on this topic (Tell et al. 2016).

To summarize, businesses in the agri-sector face difficult challenges – but have also unique opportunities to develop sustainability-oriented innovation and sustainable business models which create value in other ways than low-cost production. However, even if the needs at the global and firm levels are large, research regarding the development of sustainable business models within the agri-sector is limited. This is a significant issue, since profitable agri-companies, which develop sustainable business models and advance along the agri-value chain, need to become part of the solution at a moment in history when the world needs more food, which is to be produced and distributed in sustainable ways.

In order to reduce the research gap identified, the aim of this chapter is to illustrate and analyse how Swedish agri-companies strive to develop sustainable business models to innovate their business activities. I will illustrate, map, categorize and analyse the orientation of the practices of sustainability innovation and the development of sustainable business models. The research questions are: (i) “How do Swedish agri-companies apply sustainable innovation practices?”, (ii) “Which sustainable business models do Swedish agri-companies use?”, and (iii) “How can these innovation practices and sustainable business models be understood?”

The remaining of this chapter is organized as follows: A conceptual framework will be articulated, and, subsequently, the methodological research approach will be presented. Later on, eight Swedish cases including companies and cooperatives will be illustrated and analysed. Once these cases are discussed, some aspects of theory development will be developed. Finally, based on the most salient learnings from the research, guidelines for agri-entrepreneurs will be provided as well as suggestions for future research.

5.2 Conceptual Framework

The theory section is organized as follows: sustainability in the agri-sector, sustainability-oriented innovation, sustainable business models and eight types of sustainable business models.

5.2.1 Sustainability in the Agri-sector

The field of sustainability is a relatively new discipline that has developed over the last 15–20 years (Coad and Pritchard 2017). Nidumolu et al. (2009) showed a decade ago that sustainability became innovation’s new frontier. They stated that sustainability is a fundamental layer of organizational and technological innovations that yield both bottom-line and top-line returns. This has only escalated further during the last decade. The majority of businesses are now well aware of the importance of sustainability, which represents a key driver for innovation and a challenge in many aspects at the same time. The challenges include not only obvious aspects such as products, processes, technologies and business models but also more abstract dimensions like cognitive, psychological and organizational challenges (Sharma 2017).

Sustainability in the agri-sector is of vital importance since this large sector uses over 37% of the total land area of the world and 21% of the land area of the European Union. If forestry is included, the area used reaches 68% of the world and 46% of the European Union (FAO 2019). Further, the agri-sector represents a significant component of the EU economy, accounting for about 7% of its total exports. The agri-sector also accounts for 4.3% of the total labour market in the European Union (Eurostat 2018).

Many businesses in the agri-sector are small companies with primary production as the dominating aspect of their business. These companies need new ideas and approaches to become more profitable at the same time as they are exposed to both internal and external pressure to become more sustainable. Internal pressure to build a business on sustainable values may arise from the board, management, shareholders, family and employees. External pressure can be derived from competitors, customers, special interest groups and governmental regulation-legislation (Tell et al. 2016).

There are also actors and forces working in the opposite direction, contributing to an increasing “unsustainability” of the agri-food sector. Bernard et al. (2014) have identified actors whose impact can lead to decision-making in the agri-company which leads to unsustainability: (i) loss-making investors and credit providers who abandon farms due to low economic returns; (ii) angry neighbours and environmental activists engaging in silent or active conflict, because they are negatively affected by farming activities; (iii) dissatisfied customers at the endpoint of value chains who do not trust the quality of products or disapprove of production conditions; and (iv) overacting regulators who over-regulate farm activities. Even though each actor perceives their actions as sustainable, they can influence agri-companies’ management path towards unsustainability. Further, Fritz and Matopoulos (2008) have identified forces that can lead to unsustainability, such as (i) globalization of the agri-food industry resulting in increased imports and exports; (ii) consumer changes in consumption, resulting in a larger demand of food products, often out of season, that are transported long distances; (iii) the concentration of the sector, which has resulted in an ever-increased power imbalance in favour of retailers; and, finally (iv) major changes in delivery patterns with most goods now routed through supermarket regional distribution centres using larger heavy goods vehicles.

Despite the pressure to raise efficiency and lower costs from strong actors in the food value chain, many agri-food companies strive to conduct a sustainable business from social and ecological perspectives as well as from an economic one. Recent research (Cagliano et al. 2016) has identified three main integrated challenges for sustainability in the agri-food sector: first, the interdependency between food production and environmental, human and physical resources; second, the important role – sustainability and health aspects – of food for humans; and, third, the special characteristics of the food supply chain, with companies of different size and different sustainability focus.

The mindset and awareness of the owners and/or the managers of agri-companies can be an important factor for the development of sustainability-oriented innovation (Cagliano et al. 2016). Walker has identified this as a values-based driver (Walker 2012, 2014). Further, Barth et al. (2017) have found that many agri-food producers have a strong “value intention” to conduct their agri-business in a sustainable way. Explanations for this could be that many agri-companies are family businesses, rooted in their communities and strongly connected to the land of the ancestors. The owners/managers have experienced the effect of their actions on their land and production. They have accepted a responsibility for coming generations (Ulvenblad et al. 2016; Barth et al. 2017).

5.2.2 Sustainability-Oriented Innovation (SOI)

During the recent decades, the use of concepts connected to sustainable innovation, such as green innovation, environmental innovation and ecological innovation, have grown (Schiederig et al. 2012). In recent years, circular economy (Korhonen et al. 2018) and circular innovation (Guzzo et al. 2019) have also emerged as concepts. Bigliardi and Bertolini (2012, p 400) offer three explanations for this growing interest: “it may confer legitimacy, enhance competitiveness, and highlight ecological responsibility in an environment of both regulatory and consumer sensitization”. However, the connection between innovation and sustainability has still to be developed further (Neutzling et al. 2018). Adams et al. (2016) have, after conducting a structured literature review of both academic and grey literature, identified four shortcomings with previous work. There is uncertainty regarding what sustainability actually means and how it can be achieved, because of the large variety of different conceptualizations. Previous work also tends to treat sustainability dichotomously (sustainable/not sustainable), rather than as a dynamic, unfolding process that is achieved over time. Further, previous work often overlooks the social dimension. Finally, many reviews of environmental management and sustainability exclude contemporary grey literature.

Based on their literature review, Adams et al. (2016) developed a framework of sustainability-oriented innovation. Their perspective is that “sustainability-oriented innovation involves making intentional changes to an organization’s philosophy and values, as well as to its products, processes or practices to serve the specific purpose of creating and realizing social and environmental value in addition to economic returns” (p. 181). The framework starts as regulatory compliance with incremental change at the firm level and culminates with radical change at the large-scale systems level. The researchers claim that moving through the framework requires a step change in philosophy, values and behaviour, which will be reflected in the innovation activity of the company.

The framework is divided into three dimensions (from diminishingly unsustainable to increasingly sustainable). The first dimension, technical/people, is about a movement in the literature from a focus on technology, i.e. a “set of tools”, to a recent focus on people-centred innovation. The second dimension, stand-alone/integrated, is internal and describes how “innovation for sustainable manufacturing has moved from end-of-pipe, stand-alone solutions to modes of practice that require sustainability to be more deeply embedded in the culture of the firm” (p. 183). The third dimension, insular/systemic, reflects the firm’s view of itself in relation to a wider socio-economic system beyond the firm’s immediate boundaries and stakeholders.

These three dimensions represent three sustainability-oriented approaches on the journey to a sustainable business, operational optimization, organizational transformation and system building that a firm can have when it comes to innovation objective, outcome and relationship, defining the sustainability of the business (Table 5.1).

5.3 Business Models

Business models are descriptions of how companies create value through exploitation of business opportunities (Rosca et al. 2017). Business models can be regarded as structured management tools, which are considered especially relevant for success (Magretta 2002). The research regarding business models has been growing since the mid-1990s (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2012). In recent years, research has put a steadily increasing focus on business models (Wirtz et al. 2016).

Most of this research addresses the importance of business models for companies’ competitiveness, renewal and growth (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002; Johnson 2010; Lambert and Davidson 2013; Teece 2010). Companies can apply several business models simultaneously, regarding, e.g. different products or markets (e.g. Aspara et al. 2013; Casadesus-Masanell and Tarziján 2012).

Researchers have used a variety of business models’ definitions and settings in their studies, from the single company to the entire value network (Johnson 2010, Zott et al. 2011, Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2012). Even though empirical research on business models in 1996–2010 has focused on media, information technology and biotechnology industries (Lambert and Davidson 2013), a newly conducted structured literature review shows that the number of articles published regarding business models in food production has grown during the last 5 years (Tell et al. 2016). However, Wirtz et al. (2016) state that the growing field of research for the business model is in a consolidation phase, which still contains research gaps and thus offers possibilities for future research. The researchers suggest that research about business models’ forms and components should be empirically validated, since a certain heterogeneity regarding this research area’s focus has been determined.

Several researchers have discussed the central building elements of a business model: (i) value proposition, (ii) value creation and delivery and (iii) value capture (Bocken et al. 2014; Richardsson 2008; Osterwalder and Pigneur 2005). The value proposition is typically concerned with the product and/or service offering to generate economic return (Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013). Value creation and delivery is at the centre of any business model, and companies create and deliver value by seizing new business opportunities, new markets and new revenue streams (Beltramello et al. 2013; Teece 2010). Value capture is about considering how to manage cost structure and create revenue streams from the provision of good, services or information to users and customers (Teece 2010); see Table 5.2.

5.3.1 Sustainable Business Models

This interest in social and environmental sustainability is not new. Thirty years ago the Brundtland Report called for sustainable development that meets “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” (WCED, p. 43). Many researchers argue that more leadership is still needed around the issue of social and environmental sustainability (e.g. Kurucz et al., 2017). Researchers have also stated that a narrow focus on profitability without more attention paid to social and environmental sustainability can even limit a company’s achievement of its economic goals (Kiron et al. 2013; Schaltegger et al. 2016).

Regarding the development of the sustainability-oriented innovations field, an increasing number of scholars frame it as a business model challenge (Rohrbeck et al. 2013). Several researchers have stated that the business model concept is a productive way to study the creation and use of sustainable innovation, both in practice and in theory (Boons et al. 2013). Further, researchers have called for more studies of business models oriented towards sustainable development (Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013; Boons et al. 2013; Breuer et al. 2016; Stubbs and Cocklin 2008; Upward and Jones 2016). They have proposed alternatives to the traditional business model with its focus on maximizing growth and revenues and on minimizing costs. One alternative model is sustainable business models based on the network approach or the value-net approach (Breuer et al. 2016; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013; Kähkönen 2012; Lawson et al. 2008).

Boons and Lüdeke-Freund (2013) state that research on sustainable innovation is lacking conceptual consensus, which is needed to further develop the field. Based on a review of previous research, the authors propose a generic business model concept with four key elements:

-

(i)

Value proposition: what value is embedded in the product/service offered by the company.

-

(ii)

Supply chain: how upstream relationships with suppliers are structured and managed.

-

(iii)

Customer interface: how downstream relationships with customers are structured and managed.

-

(iv)

Financial model: costs and benefits from (i–iii) and their distribution across business model stakeholders.

These four business model elements, when combined with a perspective on social and environmental sustainability, describe a sustainable business model (Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013). Organizations committed to such sustainability integrate their social, environmental and economic activities in order to create value for their customers and for society. The sustainable business model analyses not only how organizations produce and deliver goods and services but, at the same time, how they contribute to the improvement of society – environmentally and socially. A company, cooperation or other organization with a sustainable business model is often part of, to a greater or lesser extent, a community or region that highly values the sustainable society and the sustainable environment.

Because of this increased focus on social and environmental sustainability, many companies worldwide have taken a greater interest in sequential business model innovation in which they refine an existing business model or launch a new one. The business model canvas framework (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2012) has been developed for companies to envision and implement sustainable business models in practice. One of the new tools promoted for this work is the strongly sustainable business model canvas (Jones and Upward 2014; Upward and Jones 2016). In practice, a stewardship style of leadership is required for use of sustainable business models in which leaders understand their role as temporary custodians of power. Such leaders are committed to achieving value for all organizational stakeholders, including society (Bocken et al. 2014; Harvey 2001).

When focusing on sustainable business models, Barth et al. (2017) have proposed that a fourth building element should be added to the previously defined building elements of business models, (i) value proposition, (ii) value creation and delivery and (iii) value capture (Bocken et al. 2014; Richardsson 2008; Osterwalder and Pigneur 2005), namely, (iv) value intention. Many agri-companies are owner-managed family businesses. The owners regard themselves as stewards or custodians of the company, the property and the environment, with a responsibility for living and non-living things (Ulvenblad et al. 2016, Barth et al. 2017). Research regarding sustainability-oriented innovation also stresses the importance of intentional changes to the philosophy and values of the organization (Adams et al. 2016). Including value intention of the owner-manager in the conceptual framework could present important insights of potential trade-offs and barriers when addressing growth ambitions based on social, environmental and economic aspects (Table 5.3).

5.3.2 Eight Sustainable Business Model Archetypes

The research framework, which was used to address the research questions stated above, namely, (i) “How do Swedish agri-companies apply sustainable innovation practices?”, (ii) “Which sustainable business models do Swedish agri-companies use” and (iii) “How can these innovation practices and sustainable business models be understood?”, is also based on Bocken et al.’s (2014) eight SBM archetypes. In turn, they build their archetypes on the nine business model “building blocks” of the business model canvas (Osterwalder and Pigneur (2012), Boons and Lüdeke-Freund (2013) reference. Among the blocks most relevant to our study are value propositions, key activities, key partnerships and revenue streams. Building on this key tool for the analysis of business models, Bocken et al. (2014) add sustainable social and environmental activities. They (p. 44) define SBMs as follows:

Innovations that create significant positive and/or significantly reduced negative impacts for the environment and/or society, through changes in the way the organisation and its value-network create, deliver value and capture value (i.e. create economic value) or change their value propositions.

Table 5.4 presents Bocken et al.’s (2014) eight SBM archetypes. These archetypes can be used in order to identify patterns and attributes that facilitate the categorization of the business model innovations for social and environmental sustainability. The archetypes can constitute a base for the development of a common language for the development of sustainable business models in research and practice.

5.3.3 A Combined SOI and SBM Archetypes Framework

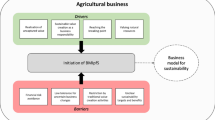

In this chapter, the framework developed by Adams et al. (2016) focusing on sustainability-oriented innovations (SOI) is integrated with the framework containing eight different SBM archetypes developed by Bocken et al. (2014) (see Table 5.5). The idea behind combining these two frameworks, which was developed by Ulvenblad et al. (2019), is to categorize the business model innovations and study the organizational development (the sustainability-oriented innovation practices and processes) taken by agri-companies in Sweden.

5.4 The Case of Sweden

Sweden is often categorized as a country leading sustainable agri-production in many areas such as environmental awareness, animal welfare, low use of antibiotics and access to high-quality natural resources (Bucht 2016). The Swedish Ministry of the Environment presented as early as 2003 a vision for sustainable development that strongly recommends all policy decisions take into account the longer-term economic, social and environmental implications (Swedish Ministry of the Environment 2003). This is a vision that applies to food producers in Sweden.

The OECD report regarding Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Sweden (OECD 2018) identifies Sweden as one of the earliest OECD countries to raise awareness of environmental issues and develop environmental policies. The result has been that the negative environmental impact has decreased, although agricultural production in Sweden has remained stable. OECD (2018, p. 12) states that: “Swedish legislation, which reflects consumer and citizen preferences, sets norms and standards for food safety, environment and animal welfare that is well above EU requirements in many areas of agriculture and horticulture. Swedish consumers and citizens have a high level of confidence for the Swedish agricultural and food system”. The majority of Swedish agri-companies regard social and environmental issues as part of their goals, besides economic revenue (Ulvenblad et al. 2019).

However, the agri-sector in Sweden is facing challenges as well. The Swedish agri-sector has undergone significant structural changes in the last 20 years. The surviving food producers have become larger through internal growth and/or mergers and acquisitions (Swedish Board of Agriculture 2018). Others have been forced into subcontractor roles with diminished managerial influence on production goals and activities. This power asymmetry, combined with low-quality business relationships, can lead to suboptimization of resources and a reduced capacity to identify and satisfy consumer needs (Benton and Maloni 2005; Schulze-Ehlers et al. 2014). Furthermore, some larger companies in higher positions in the food value chain may not share smaller companies’ interest in social and environmentally sustainable innovation. Even when such sustainable innovation (sometimes in response to consumer pressure) improves a product’s quality, these larger companies may be disinclined to adopt the innovations for use in their production activities, delivery systems and product portfolios. They hesitate primarily because of fear of greater logistics complexity and higher costs. In some instances, however, these structural changes in the agri-sector have resulted in more cost-effective production and distribution systems, although with survival and profit still greater concerns than social and environmental issues. Thus, many stakeholders (e.g. consumers, consumer rights organizations, the media and citizens) are asking for healthy food and more sustainable social and environmental innovation in the agri-sector.

This pressure from stakeholders combined with the situation with declining profits in spite of production efficiency and economies of scale has led many agri-companies to develop their business models towards sustainability and high-quality products. Further, many agri-companies try to advance in the agri-value chain and get closer to the final customer.

To summarize, it seems likely that Sweden, as one of pathfinders in the world regarding sustainability and innovation, can contribute in the strive towards an innovative and sustainable agri-sector. Considering the global needs and challenges, it is important to deepen the international cooperation regarding the development of sustainable business models in the agri-sector. Hence, by studying the Swedish context, we can identify barriers, challenges and possibilities that can be relevant in other countries as well.

5.5 Methodology

In this paper, I will present, discuss and analyse eight different agri-companies/agri-cooperatives connected to agriculture in Sweden. Since forestry is an integrated part of agri-companies of Sweden and often an important part from cash flow and solidity perspectives, I have also studied one organisation, a large cooperative, from the forestry sector. All the companies/cooperatives are presented in Table 5.6.

The empirical data consists of both primary and secondary data, which have been collected by a set of different methods. The primary data consists mainly of interviews with owners/managers or other representatives of the companies and visits on the company/farm. Initially, the respondents were asked to tell their story of the companies in their own words. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was also used. It covered subjects like company history, past and current business activities, customers, partnerships, networks, goals, culture, values, sustainability, innovation and business models.

The secondary data has been gathered through document studies (official economic records, printed material and Internet pages). This multi-method approach has been used in previous research on business models (Täuscher and Laudien 2018; Zott and Amit 2008). In the study presented in this chapter, multiple methods have been used for each case, but not all methods have been used for all cases. The collected data, including the interviews, have been analysed through categorizations and content analysis (Täuscher and Laudien 2018).

5.5.1 Högared Milk Farm

Högared’s main business is to produce and sell milk to a large milk distributor higher up in the value chain. Currently, there are 190 milk cows at the farm. The company is owned by two brothers with their families. Besides the two owners, there are six employees at the company. The company has historically experienced few possibilities to develop and change the business model. However, during the last decade, the owners/managers have prioritized their competence building through several leadership and management courses and have now formulated a new vision for the company:

Our vision is to be a well-functioning farm for animals and humans, a modern machine station with the customer in focus. As a company, we want to build a good reputation in our district.

They have diversified their business model and activities in several directions; they have started a mechanical workshop and a custom for hire service. In the workshop, farming companies and other companies can buy services as maintenance and repair of vehicles and farming machinery. In the custom for hire service, the customer can buy services such as harvesting, applying fertilizers and pesticides, etc. Recently, the company has diversified even more, starting to sell a small fraction of its milk production directly to end consumers in their farm shop and in some of the larger groceries in the neighbouring city.

The owners have developed the sustainability focus of the company step by step. They started their journey towards sustainability according to the archetype “maximize material and energy efficiency”, which still remains as the dominating archetype. It also means that from a sustainability-oriented innovation perspective, they are focusing on operational optimization (“doing more with less”).

The development of their sustainable business model is underway. A minor part of their business model fits the archetype “deliver functionality, rather than ownership”. Further, the managers have continuously developed their stewardship role over the last years (which could be seen in the vision of the company). The company’s sustainable business model is moving towards organizational transformation (“doing good by doing new things”).

5.5.2 Gäsene Dairy

Gäsene Dairy is a dairy cooperative company owned by 28 small- and medium-sized milk farms (between 30 and 500 milk cows on each firm). The dairy’s main business is production and selling of high-quality cheese.

The dairy was founded in 1930, when milk prices were low and it was difficult for the producers to get good enough prices. Farmers in one neighbourhood developed a new business model before the concept was even conceptualized. They joined together in a cooperative association and started their own dairy, which produced and sold milk, cheese and other dairy products. The vicinity was important for the founders of the dairy, and it is still important today. All the milk are produced on farms which are situated within 25 minutes travel time from the dairy. Most of the milk and cheese are sold in groceries in southern Sweden. A minor part is sold directly to end consumers at the dairy. The quality of their products, based on sustainability and closeness, has made their brand well-known. Last year, the dairy had over 100 bus loads with visitors, exceeding 23,000 visitors. The dairy has recently decided to use biofuel for heating its premises. The surplus heat will be used for heating of the neighbouring municipality senior housing.

Since the dairy products create larger value for end customers than the products sold by large international processing companies, the dairy company can sell their products at higher prices. Consequently, the farms owning the dairy have larger revenues than other farms which deliver to the large international processing companies.

The business model of the company as such has not changed much since the company was founded, but the development of society has renewed it. From the start, the business model was based on economic necessity but also on the founding farmers’ stewardship perspective. A business that was regarded as out of date has now become both modern and sustainable. One of the owners says:

We have been out of fashion for 70 years, but now we are modern and in the front again.

Since sustainability became an important societal concept during the last decade, the company focuses even more on sustainability. The investment decision regarding the biofuel heater, which will benefit both the company and the senior housing, is one indication of the sustainability focus. Further, the company has changed its communication with customers and emphasized values as quality, vicinity and sustainability.

The founding and succeeding farmers have over time acted based on a “stewardship perspective”. Due to the societal change, the dairy matches the SBM archetype “repurpose the business for society/environment”. It also matches “substitute with renewables and natural processes”.

From a sustainability-oriented innovation perspective, their company has covered all three dimensions. Even though the dairy was founded in order to reach operational optimization (doing more with less), the stewardship perspective with focus on vicinity and sustainability in combination with societal change has led to organizational transformation and system building.

5.5.3 The Gudmund Farm

The Gudmund Farm is a farm charcuterie, which also conducts pig breeding and production. The company was founded in 1998 and produces high-quality sausages and other meat products. Fresh and processed meat products are sold in the farm shop, in other farms’ shops and in the groceries in the city. The meat comes from the farm or from subcontractors, farms in the neighbourhood. The company has long-term spoken agreements with the subcontractors, based on trust and a handshake. The sausages are handcrafted by old methods and have no additives other than natural spices and herbs. The company has diversified its products and activities continuously over the years. The company develops new sausage varieties and other meat products. Some of the new products have been developed by the employees of the company. Recently, the owners have also started to provide courses in sausage craftsmanship, food waste minimization and nutrition. Even though one goal of courses is to generate some revenue, the main reason is to educate customers. The company has also started a restaurant at the farm, where they serve lunch and arrange conferences. In order to get closer to the end customers and to learn their needs and expectations, the company opened a shop in the city close to the farm charcuterie, in 2005.

An important part of the business model is to develop and nurture long-lasting cooperation with customers, other companies, subcontractors and neighbours. The owner is also explicit regarding sustainability:

Our company and our farm will stay where it is. Of course, we have to take good care of our land, our employees, our neighbours and our animals. We also want to create win-win relationships with customers, sub-contractors and other companies.

The company matches three SBM archetypes: (i) encourage sufficiency, (ii) substitute with renewables and natural processes and (iii) adopt a stewardship role.

From the start, the company has been run by the owner with a clear and explicit stewardship perspective, where sustainability is a central theme. The owner stresses the importance of local and professional networks. The company was the first to apply this perspective when it started the business 20 years ago. Since then other companies have followed suit. From a sustainability-oriented innovation perspective, the company is conducting system building through the strategy of working in networks with a win-win focus.

5.5.4 Ästad Vineyard

Ästad Vineyard used to be a traditional farm, with 100 hectares of fields, meadows and pastures, producing milk and grain. The previous owner, and father of the current owners, changed to ecological milk production in the mid-1980s in order to raise the low profitability of the farm. That was the starting point for a continuous and ongoing sustainable business model development. The next step was to invite school classes with fifth graders to come and have an experience of the farming activities. It developed into a team-building concept, where companies could bring their employees to the farm and solve intellectual and practical problems together.

The current owners, three siblings, improved the old farm buildings and built some additional buildings, which they used to develop the business model with a spa integrated with the small river, a restaurant, a conference centre, a hotel and a winery/vineyard. Today, they have 15,000 vines, and the wine is sold to distributors and directly to end consumers at the restaurant. An important and explicit building block of their business model is to use and develop the resources of the farm, the small river, the buildings, the vegetables, the wine, etc. The owners claim that:

By experience we know that every challenge we meet also leads to new opportunities.

The family was conducting a traditional farm business from its inception. A desire to increase profitability and catch opportunities led to diversification and continuous business development. The sustainability aspect was based on partly an identification of the farm and land as a key asset from a business perspective and partly on a stewardship perspective. The company matches three SBM archetypes: (i) deliver functionality, rather than ownership, (ii) substitute with renewables and natural processes and (iii) adopt a stewardship role.

From a sustainability-oriented innovation perspective, this firm is at the organizational transformation level (“doing good by doing new things”).

5.5.5 Wapnö Farm

Wapnö Gård is an estate with an old history. It has been one of largest farming estates in Sweden since the fourteenth century. The current owner’s family has owned Wapnö since 1741. Today, Wapnö is organized as a limited company and has about 85 employees.

Wapnö Farm used to be an ordinary, although large, farm producing milk. The owners and management regarded the farm as a producer at the onset of the agri-food value. The milk was delivered to a large organization, which now has become an actor on the international market. Over 20 years ago, the owner and the management decided to start developing a diversified sustainable business model. They choose to advance in the agri-food value chain and get closer to the end consumer. Wapnö focused on sustainable environment and the preferences of the end customers, e.g. taste and flavour experiences. Today, the management of Wapnö talks about “sustainability into the future”. Wapnö has been working actively towards a sustainable environment for many years. The manager states that:

the present generation should take care in using natural resources reasonably and being environmentally responsible so that we leave the environment as untouched as possible for future generations.

Wapnö is developing a circular economy with a diversified sustainable business model. Wapnö call themselves an open farm, which means that consumers can come to the farm to get a closer look at the animals, the barns and the dairy. Wapnö also has a restaurant, which uses ingredients from the farm.

The company has established a farm brewery, and the beer is brewed from the farm’s water and grain. The cattle are moving freely and never given antibiotics. The cattle are not given soy products, but rather pressed canola. Wapnö is also producing biofuel from canola oil. The milk flows directly in a tube from the barn to the dairy 30 meters away. Wapnö also has a large greenhouse, where they grew vegetables for sale in the farm shop and for the farm restaurant. The greenhouse is heated with renewable energy generated on the farm.

Wapnö farm biogas, produced from cattle manure, contributes to renewable energy in the form of electricity, heat and cooling, which is needed year-round in the food premises. Wapnö only uses manure from animals on the farm for biogas production and has cut the energy consumption with more than 90%. The biogas plant also provides fertilization, which improves the fertility and value of the farmland.

Through the development of a sustainable diversified business model, Wapnö has climbed the value chain, got closer to the end consumer and developed a very strong brand. Therefore, it is able to sell its products at a higher price, which reflects the value end customers put on the products.

As many other farms, Wapnö used to be a traditional, although large, farm business in the start of the agri-value chain. Over the last 20 years, Wapnö has developed a diversified sustainable business model, and the development is still ongoing. Today, the company matches several business model archetypes. Wapnö maximizes its resources, creates value from waste and substitutes with renewables and natural processes. Further, the company has repurposed the business for society/environment since the sustainability and circular economy are in focus. Finally, and not least, the stewardship role is very clear and articulated.

From a sustainability-oriented innovation perspective, Wapnö is a good example of a company which has developed sustainability as a process. The company has developed from operational optimization to organizational transformation: doing good by doing new things. It could also be argued that the company has developed to system building. Although the company is mainly working as an entity, the farm is large and has advanced to a form of system building, where one part of the farm is supporting – and getting support – from other parts of the farm.

5.5.6 Green Farms

In the beginning, Green Farms used to be run as a traditional farm by the current owner’s father. When the son, the current owner, took over the company, he wanted to focus on sustainability and converted it to organic production in 1989. At first, sales did not go according to plan and the cash flow was below expectations. He could not afford to feed the cattle with expensive concentrate, so he had to feed the cows with cheaper roughage, grass in different forms. This meant that his cattle grew slower and were older than normal at slaughter. The owner expected that the meat would then be of low quality and hard to sell at a good price. However, he soon realized that the meat was of very high quality. Since it also was produced in a more sustainable way than before, it could be sold to a premium price to customer wanting high-quality meat.

Twelve years later, in 2001 he started Green Farms. The business model was to create a network of farms that raised and feed cattle in the same way as the first farm. A new farm can get into the network after a trial period, if they meet the sustainable production requirements of Green Farms. The farms have to focus on animal health, sustainability and meat quality. The network members deliver their meat to Green Farms, which sells, through the Internet, and distributes high-quality meat to the end customers, restaurants, public kitchens and individuals. Green farms cooperate with around 40 sustainable cattle farms in the southwest of Sweden.

When the present owner took over the farm from his father, he wanted to transform it into a sustainable farm. He took a stewardship role from the start and substituted the production processes to more sustainable processes. From a sustainability-oriented perspective, he had developed his company through all three phases. Today, the company has developed into system building, since the company has developed a scale-up solution and engaged other companies in the system.

5.5.7 The South Forest Owners (Södra)

The farmers who owned forest began to organize themselves as a forest owner association in the beginning of the twentieth century. The southern and middle part of Sweden was almost a deforested country at that time, due to bad forest management and short-sighted profit-maximizing forest companies. In the beginning, the forest association provided advisory services regarding forest management. However, one significant issue for the small forest farmers was that the market was dominated by few large forest companies. Hence, the small forest farmers could not get fair prices for their product or for their forests. As a response to this situation, their cooperative soon developed to coordinate distribution, sales and processing of timber and other forest-based products. Over the years many small forest cooperatives merged, and the large cooperative association Södra was formed in 1938.

Today, Södra has 51,000 small forest owners as members/owners. A large majority of these forest owners are very engaged in sustainable forestry. Many of them have been engaged even before sustainability was a concept in research and regulation. In fact, over time some of the forest owners have refused to manage their forests the way the authorities required, since the forest owners believed they could manage their forests in more sustainable ways. Södra states that:

the overall mission of the owners is to secure the provision for the members’ forest raw material and promote forestry profitability through advice and support, so that the members’ forests can be managed responsibly and with sustainability and to contribute to a market-based return on the forest raw material.

The timber from the forest farms is refined in Södra’s industries for sawn and planed timber products, interior wood products, biofuel and pulp for the market in the market. Södra runs one of Europe’s largest sawmill operations and is one of the largest producers of softwood pulp. Södra also produces textile pulp of hardwood. Their three pulp mills have almost fossil-free production and generate a large energy surplus. This bio-based energy is sold, among other things, as green electricity and district heating. Södra also owns manufacturing company, which produces one-family houses. Södra claims that they are focusing in innovation in order to develop new products, based on the renewable wood raw material.

Södra is emphasizing sustainable forestry and a sustainable forest value chain. This means, among other things, that efforts are taken to ensure that members’ forestry is conducted using methods that ensure the production capacity of forest land and forests as well as conservation of ecosystem services and biodiversity. Södra mainly uses biofuels for the industrial production processes. The energy surplus is delivered in the form of electricity to the open market, district heating to places near pulp mills and sawmills and solid biofuels for heating plants. Through the industrial activities, the forest raw material contributes to the local community’s conversion to a more sustainable energy use. Efficient use of the forest raw material from a material and energy perspective creates new conditions for sustainable products.

Even though Södra is based on small-scale forestry with strong local roots and local relations, it has ascended in the forest value chain and developed to a large international actor. A large majority of the small forest farms are run by owners who regard themselves as stewards. The stewardship perspective is also clearly communicated by their large cooperative Södra. Södra is applying several sustainable business model archetypes besides stewardship, maximize, create value from waste and develop scale-up solutions. Hence, Södra’s sustainability-oriented process is covering all three steps, encompassing system building.

5.5.8 The Farmers (Lantmännen)

The Farmers in Sweden started to organize in the end of the nineteenth century, and they founded the national association in 1905. Today, it is an economic cooperative, owned by 27,000 Swedish farmers, and has grown to one of the largest actors in agriculture, food and energy in Northern Europe.

The Farmers’ focus is to provide the members with seed, fertilizer, plant protection products and feed as well as to receive, store, refine and sell what farmers grow. Other important elements of the business are sales of forest, construction and agricultural machinery. The Farmers is the largest purchaser of grain in Sweden. They claim that they protect the earth’s resources in a responsible manner and are included in the entire value chain from farm to table. Their business model strives to deliver sustainable products and new innovative solutions to customers while at the same time creating value for our owners and contributing to a viable agriculture.

The visions and goals of The Farmers are closely connected to innovation and sustainability.

In 2018, The Farmers (Lantmännen in Swedish) was named one of Sweden’s most sustainable brands (Sustainable Brand Index 2018). The Farmers strive after viable agriculture, greener energy and a sustainable food chain. The Farmers state that,

Together we take responsibility from land to table…. we lead the processing of arable land resources in an innovative and responsible manner for tomorrow’s agriculture… we create a viable agriculture.

The Farmers shares several aspects with Södra. Many of the small farm owners have also sustainability priorities and have stewardship perspectives. The Farmers has also developed applying several sustainable business model archetypes besides stewardship, maximize, create value from waste and develop scale-up solutions. From a sustainability-oriented perspective, The Farmers are also involved in system building.

5.6 Analysis

The eight companies and cooperatives will be positioned in the combined framework of sustainability-oriented innovations (SOI) and different sustainable business model archetypes. See Table 5.7.

All of the companies analysed share a stewardship perspective on the business. All of them are also regarding themselves as entrepreneurs and business leaders, not only producers. Further, all of companies have over time developed and moved closer to customers in the agri-value chain. Another relevant aspect of their sustainable business models is that they have diversified their business models. Since these companies are depending on natural resources and often connected to one place, it is hard for them to develop scale-up solutions. However, one way to develop scale-up solutions is to organize themselves into larger cooperatives, like Södra and Lantmännen.

All companies are closely connected to the real estate where they are situated. The companies, all of which are owner-managed, are family businesses in which the families expect to retain ownership for the foreseeable future. As family businesses strongly rooted in their communities, the owners are not concerned solely with growth and revenues. The owners think of themselves as stewards or custodians of the company, the property and the environment, with responsibility for living and non-living things. Cooperation in network structures or cooperatives is important for these companies. Trust, common values, other-orientation and win-win perspective are crucial concepts in the network structures.

5.7 Conclusions, Future Research Avenues and Practical Implications

The research presented in this chapter builds on, and adds to, previous research regarding sustainability-oriented innovation (Adams et al. 2016), business model archetypes (Bocken et al. 2014) and building blocks of business models (Barth et al. 2017).

The sustainability-oriented innovation framework regards sustainability as a continuous process that is developed and achieved over time (Adams et al. 2016). Their study has also shown how organizations can develop to become more sustainable. Further, they suggest that the development of sustainability-oriented innovation often starts with intentional changes to the values of the organization and as a response to regulation.

The analysis based on the cases of the study presented in this chapter deepens the knowledge regarding why agri-entrepreneurs develop the sustainability aspects of their business model. This study shows that many agri-entrepreneurs have a stewardship intention and want to develop and preserve their company, relationships and environment for the future and coming generations. Some agri-entrepreneurs applied the values of sustainability even before the concept was used in literature and discourse. The agri-entrepreneurs who strive for sustainability are often ahead of, or even in conflict with, legislation and policy when they develop their sustainable business models.

The aim of the eight sustainable business model archetypes developed by Bocken et al. (2014) is to “develop a common language that can be used to accelerate the development of sustainable business models in research and practice”. In the study presented here, stewardship is a frequent and important sustainable business model archetype. The stewardship archetype seeks to “maximize the positive societal and environmental impacts of the firm on society by ensuring long-term health and wellbeing of stakeholders (including society and the environment)”. According to researchers behind such archetype, it can preferably be used in combination with other archetypes. Based on the analysis in this study, the stewardship role is of paramount importance. However, it could be argued that stewardship should not be regarded as a business model archetype. Rather, it is an explanation or an incentive for developing sustainable business models.

The frequent use of adopting a stewardship role can be explained by the unique characteristics of the agri-sector. As Cagliano et al. (2016) have shown, there is a clear interdependency between agriculture and environmental, human and physical resources. Walker 2012 and 2014 have also pointed on the awareness of the entrepreneur as a value-based driver for sustainable business models. Ulvenblad et al. (2016) and Barth et al. (2017) have elaborated on this relationship. The owners/managers regard themselves as stewards or custodians of the company, the property and the environment, with a responsibility for individuals, animals and growing things. The company is often based on a farm, which has been owned by the ancestors before. The company is depending on the resources of the land, and it is going to stay where it is. Relations to neighbours and other companies are also important and have to be managed and maintained. The stewardship perspective is important when developing sustainable business models in the agri-sector.

Barth et al. (2017) have suggested that when studying the development of sustainable business models, the building block “value intention” should be added to previously developed building elements of the conceptual business model framework: (i) value proposition, (ii) value creation and delivery and (iii) value capture (Bocken et al. 2014; Richardsson 2008; Osterwalder and Pigneur 2005). Sustainability-oriented research also underlines the philosophy and values of the organization (Adams et al. 2016). Based on the cases presented in this chapter, the value intention is an important base for a sustainable business model in the agri-sector. Hence, it seems relevant to include the value intention element into the conceptual business model framework as well. Including the value intention of the owner-manager in the future theory building could present important insights of potential trade-offs and barriers when addressing growth ambitions based on social, environmental and economic aspects.

Future research might also examine how agri-companies innovate their sustainable business models when they introduce new products and engage in new business activities. It would also be relevant to further deepen the understanding of the connection with the special challenges in the agri-sector (Cagliano et al. 2016), the importance of the value intention (Barth et al. 2017) and value-based drivers for sustainable innovation (Walker 2012, 2014). The case study approach is well-suited for such studies.

Another relevant question to further investigate is a comparative analysis of the sustainable business model concept among industries. “Literature indicates that a wide range of traditional SMEs are still mostly focused on harvesting low hanging fruits by engaging primarily in incremental innovation” (Klewitz and Hansen 2014). The results from the agri-sector in Sweden show that there are companies in the agri-sector that optimize their operation with doing more with less, but the majority states that they focus on organizational transformation or even system building. Further, many of the owners/managers of the agri-companies adopt a stewardship perspective. Hence, many companies in other industries, and not only SMEs, can gain inspiration, insights and experiences and learn from the agri-sector.

5.8 Practical Implications

If agri-entrepreneurs and society focus on added value higher up in the value chain rather than only on efficiency at the inception of the value chain, it will be natural to emphasize the importance of agri-businesses for a sustainable society. Instead of a focus on the negative climate and environmental impact of production, focus can be on creating added value from climate and environmental perspectives.

A growing awareness and understanding of these values increases the opportunities for agri-companies to obtain higher prices for their products and/or services. Agri-companies can then focus more on how sustainable innovations can be developed. The climate and environmental perspectives will then become an opportunity and not a limitation for agri-companies and society.

Extension services focused on the agri-sector should reinforce the concept of agri-entrepreneurs as entrepreneurs instead of just producers. The efforts should focus on new, sustainable business models that encompass more links in the value chain than primary production. This means that education and counselling to businesses should focus on leadership, business development and innovation. The dissemination of knowledge should be conducted through coaching, in order to strengthen the competence and ability of the agri-entrepreneur.

5.9 Concluding Remarks

It is important for sustainable development to further emphasize the importance of innovations in the agri-sector, not only for the agri-companies themselves but also as a response to many of the challenges society faces. While social development has benefited major cities and urban centres, rural areas and agri-companies have substantial opportunities and resources to contribute to the solutions to many of our major social challenges today. These social challenges apply to several major and comprehensive issues such as:

-

Climate and environment

-

Integration, diversity and gender equality

-

Labour and employment

-

Access to housing

-

The degree of self-sufficiency of society

Agri-companies and agri-entrepreneurs are often situated in rural areas. They can provide solutions to these challenges. Their owners are aware that their companies are connected to a village, a place. They are aware, sometimes intuitively, that the family, the farm, the place and the company will exist in the future - even after they leave business. Therefore, they have every reason to take care of relationships, neighbours, companies, land and animals. Agri-entrepreneurs are aware of their responsibility for future generations and have opportunities to contribute to environmental and climate solutions, which are some of today’s major issues. Their mindsets and value intentions ought to be spread in society in general. These agri-entrepreneurs are stewards in the best sense of the word.

References

Adams R, Jeanrenaud S, Bessant J, Denyer D, Overy P (2016) Sustainability-oriented innovation: a systematic review. Int J Manag Rev 18(2):180–205

Alston J (2010) The benefits from agricultural research and development, innovation, and productivity growth. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 31, OECD Publishing, Paris

Alston J (2018) Reflections on agricultural R&D, productivity, and the data constraint: unfinished business, unsettled issues. Am J Agric Econ 100(2):392–413

Aspara J, Lamberg J-A, Laukia A, Tikkanen H (2013) Corporate business model transformation and inter-organizational cognition: the case of Nokia. Long Range Plan 45(6):459–474

Barnett ML, Salomon RM (2012) Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strateg Manag J 33:1304–1320

Barth H, Ulvenblad P-O, Ulvenblad P (2017) Towards a conceptual framework of sustainable business model innovation in the agri-food sector: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 9:1620

Beltramello A, Haie-Fayle L, Pilat D (2013) Why new business models matter for green growth. OECD, Paris

Benbrook CM, Butler G, Latif MA, Leifert C, Davis DR (2013) Organic production enhances milk nutritional quality by shifting fatty acid composition: a United States-wide, 18-month study. PLoS One 8(12):E82429. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082429

Benton WC, Maloni M (2005) The influence of power driven buyer/seller relationships on supply chain satisfaction. J Oper Manag 23(1):1–22

Bernard F, van Noordwijk M, Luedeling E, Villamor GB, Sileshi GW, Namirembe S (2014) Social actors and unsustainability of agriculture. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 6:155–161

Beuchelt TD, Zeller M (2012) The role of cooperative business models for the success of smallholder coffee certification in Nicaragua: a comparison of conventional, organic and organic-Fairtrade certified cooperatives. Renew Agric Food Syst 28(3):195–211

Bigliardi B, Bertolini M (2012) Green innovation management: theory and practice. Eur J Innov Manag 15(4)

Bocken N, Short S, Rana P, Evans S (2014) A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J Clean Prod 65:42–56

Boons F, Lüdeke-Freund F (2013) Business models for sustainable innovation: state-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J Clean Prod 45:9–19

Boons F, Montalvo C, Quist J, Wagner M (2013) Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: an overview. J Clean Prod 45:1–8

Breuer H, Fichter K, Lüdeke-Freund F, Tiemann I (2016) Requirements for sustainability-oriented business model development. Paper presented at the 6th International Leuphana Conference on Entrepreneurship, 14–15th January, Lüneburg

Bucht S (2016) A National Food Strategy for Sweden – more jobs and sustainable growth throughout the country. Short version of Government bill 2016/17:104

Cagliano R, Worley CG, Caniato FF (2016) The challenge of sustainable innovation in agri-food supply chains. In: Caniato FF, Worley VG (eds) Cagliano R. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Organizing supply chain processes for sustainable innovation in the agri-food industry, pp 1–30

Casadesus-Masanell R, Tarziján J (2012) When one business model isn’t enough. Harv Bus Rev 90(1/2)

Chesbrough H, Rosenbloom RS (2002) The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation’s Technology Spinoff Companies. Ind Corp Chang 11(3):529–555

Coad N, Pritchard P (2017) Leading sustainable innovation. A Greenleaf Publication book. Routledge, London

Dobermann A, Nelson R (2013) Opportunities and solutions for sustainable food production. Paper for the high-level panel of eminent persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 15th January 2013

European Commission (2011) Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions, Horizon 2020 – The Framework Programme for Research and Innovation

European Commission (2016), Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions, next steps for a sustainable European future – European action for sustainability

Eurostat (2018) Agriculture, forestry and fishery statistical book. ISBN 978-92-79-94757-5, https://doi.org/10.2785/340432, Cat. No: KS-FK-18-001-EN-N

FAO (2011) The state of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture (SOLAW) – managing systems at risk. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome and Earthscan, London

FAO (2019) Food and agriculture data, FAOSTAT

Fritz M, Matopoulos A (2008) Sustainability in the agri-food industry: a literature review and overview of current trends. Conference: 8th International Conference on Chain Network Management in Agribusiness the Food Industry, May 2008, Wageningen

Fuglie K, Clancy M, Heisey P, MacDonald J (2017) Research, productivity and output growth. US Agric J Agric Appl Econ 49(4):514–554

Griggs D, Stafford-Smith M, Gaffney O, Rockström J, Öhman MC, Shyamsundar P, Noble I (2013) Policy: sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 495(7441):305–307

Guzzo G, Hofmann Trevisan A, Echeveste M, Hornos Costa JM (2019) Circular innovation framework: verifying conceptual to practical decisions in sustainability-oriented product-service system cases. Sustainability 11(12):3248

Harvey M (2001) The hidden force: a critique of normative approaches to business leadership. SAM Adv Manag J 66(4):36

IPCC (2019) Summary for policymakers. In: Special Report on Climate Change and Land. An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland

Johnson MW (2010) Seizing the white space: business model innovation through growth and renewal. Harvard Business School Publishing, Brighton, MA, USA

Jones P, Upward A (2014) Caring for the future: the systemic design of flourishing enterprises. In The third symposium of relating systems thinking and design (RSD3), Oslo, pp 1–8

Kähkönen A-K (2012) Value-net – a new business model for the food industry? Br Food J 114(5):681–701

Kiron D, Kruschwitz N, Haanaes K, Reeves M, Goh E (2013) The innovation bottom line. MIT Sloan Management Review Research Report Winter 2013. Cambridge

Klewitz, J, Hansen, E (2014) Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: a systematic review. J Clean Prod 65:57–75

Korhonen J, Nuur C, Feldmann A, Birkie SE (2018) Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J Clean Prod 175:544–552

Kurucz, E, Colbert, B, Lüdeke-Freund, F, Upward, A, Willard, W (2017) Relational leadership for strategic sustainability: practices and capabilities to advance the design and assessment of sustainable business models. J Clean Prod 140:189–204

Lambert S, Davidson R (2013) Applications of the business model in studies of Enterprise success, innovation and classification: an analysis of empirical research from 1996 to 2010. Eur Manag J 31(6):668–681

Lawson R, Guthrie J, Cameron A (2008) Creating value through cooperation - an investigation of farmers’ markets in New Zealand. Br Food J 110(1):11–25

Lobell DB, Burke MB, Tebaldi C, Mastrandrea MD, Falcon WP, Naylor RL (2008) Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science 319(5863):607–610

Magretta J (2002) Why Business Models Matter. Harv Bus Rev 80(5):86–92

Neutzling DM, Land A, Seuring S, Nascimento LFM (2018) Linking sustainability-oriented innovation to supply chain relationship integration. J Clean Prod 172:3448–3458

Nidumolu R, Prahalad CK, Rangaswami MR (2009) Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harv Bus Rev 2009:57–64

OECD (2016) Agricultural Outlook 2016–2025. OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2018) Innovation, agricultural productivity and sustainability in Sweden, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews. OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2019) Agricultural policy monitoring and evaluation 2019 (summary). OECD Publishing, Paris

Osterwalder A, Pigneur Y (2005) Clarifying business models: origins, present and future of the concept. Commun AIS 15:1–25

Osterwalder A, Pigneur Y (2012) Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Wiley, Hoboken

Richardsson J (2008) The business model: an integrative framework for strategy execution. Strateg Chang 17(5–6):133–144

Rohrbeck R, Konnertz L, Knab S (2013) Collaborative business modelling for systemic and sustainability innovations. Int J Technol Manag 63:4–23

Rosca E, Arnold M, Bendul JC (2017) Business models for sustainable innovation – an empirical analysis of frugal products and service. J Clean Prod 162 suppl, S133–S145

Schaltegger S, Hansen E, Lüdeke-Freund F (2016) Business models for sustainability: origins, present research, and future avenues. Organ Environ 29:3–10

Schiederig T, Tietze F, Herstatt C (2012) Green innovation in technology and innovation management– an exploratory literature review. R D Manag 42(2):180–192

Schulze-Ehlers B, Steffen N, Busch G, Spiller A (2014) Supply chain orientation in SMEs as an attitudinal construct. Supply Chain Manag 19(4):395

Sharma S (2017) Competing for a sustainable world. Building capacity for sustainable innovation. A Greenleaf publication book. Routledge, London

Średnicka-Tober D, Barański M, Seal C, Sanderson R, Benbrook C, Steinshamn H et al (2016) Composition differences between organic and conventional meat: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 115(6): 994–1011

Stubbs W, Cocklin C (2008) Teaching sustainability to business students: shifting mindsets. Int J Sustain High Educ 9(3):206–221

Sustainable Brand Index (2018) Official report Sweden

Swedish Board of Agriculture (2018) Agricultural statistics

Swedish Ministry of the Environment (2003) A Swedish strategy for sustainable development: economic, social and environmental

Täuscher K, Laudien SM (2018) Understanding platform business models: a mixed methods study of marketplaces. Eur Manag J 36(3):319–329

Teece DJ (2010) Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan 43(2–3):143–462

Tell J, Hoveskog M, Ulvenblad P, Ulvenblad P-O, Barth H, Ståhl J (2016) Business model innovation in the Agri-food sector: a literature review. Br Food J 118(6):1462–1476

Thornton PK, Schuetz T, Förcha W, Cramer L, Abreu D, Vermeulen S, Campbell BM (2017) Responding to global change: a theory of change approach to making agricultural research for development outcome-based. Agric Syst 152(March):145–153

Ulvenblad P-O, Ulvenblad P, Tell J (2016) Green innovation in the food value chain—Will Goliath fix it—or do we need David? In: Proceedings of the 61st International Council for Small Business (ICSB) World Conference, New York, 15–18 June

Ulvenblad, P-O, Ulvenblad, P, Tell, J (2019) An overview of sustainable business models for innovation in Swedish agri-food production. J Integr Environ Sci 16 (1):1–22

United Nations (2015) Global sustainable development report. United Nations, USA

Upward A, Jones P (2016) An ontology for strongly sustainable business models defining an enterprise framework compatible with natural and social science. Organ Environ 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026615592933

Walker S (2012) The narrow door to sustainability–from practically useful to spiritually useful artefacts. Int J Sustain Design 2(1):83–103