Abstract

As the climate changes, natural disasters are becoming more frequent and severe. Some disasters are sudden and briefly devastating. Research shows that, in response, many people emigrate temporarily but return when the danger is past. The effect of slow-onset disasters can be equally disruptive but the economic and social impacts can last much longer. In Australia, extreme heat and the rising frequency of heat waves is a slow-onset disaster even if individual periods of hot weather are brief. This chapter investigates the impact of increasing heat stress on the intention of people living in Australia to migrate to cooler places as an adaptation strategy using an online survey of 1344 people. About 73% felt stressed by increasing heat of which 11% expressed an intention to move to cooler places in response. The more affected people had been by the heat, the more likely they were to intend to move. Tasmania was a preferred destination (20% of those intending to move), although many people (38%) were unsure where they would go. As Australia becomes hotter, heat can be expected to play a greater role in people’s mobility decisions. Knowing the source and destination of this flow of internal migrants will be critical to planning and policy-making.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

8.1 Introduction

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency and severity of many weather-related disasters, including floods, storms, droughts and heat waves. Heat wavesFootnote 1 are the most dangerous natural hazard worldwide (Fang et al. 2015). The 2003 heat wave in Europe, for example, killed more than 70,000 people (Robine et al. 2008), particularly older people and those with illnesses (see Chap. 10 as well on 2009 south-eastern Australia heatwave). As climate change increases, the frequencies of heat waves (Perkins et al. 2012; Perkins and Alexander 2013) mortality and morbidity rates will also rise from associated disasters such as bushfires and droughts. Temperatures are also increasing in general due to climate change (Coumou et al. 2013), and this increased exposure to heat, even if not on consecutive days, are also of public health concern. Being exposed to too much heat can cause heat stress and associated illness with symptoms, ranging from being uncomfortable to hot flushes, headaches, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, cramps and, eventually, heat strokes and collapse (Parsons 2003). Any of these symptoms can compromise people’s wellbeing and productivity (Zander et al. 2015).

Short-term in-situ adaptation to heat includes hydration (drinking), cooling (including air-conditioning) and resting. In the long-term, however, adaptation plans to heat and heat waves must include alterations to infrastructure such as insulation, ventilation, air-conditioning (Barnett et al. 2015; Hatvani-Kovacs et al. 2016) as well as landscape design. The latter is likely to be particularly important in cities suffering from higher temperatures as a consequence of human activity, known as the heat island effect (Solecki et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2014).

Migration is the most extreme form of adaptation to heat stress. Migration as an adaptation to climate change has been recognised since the first report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as well as debated extensively in academic literature focused on developing countries (Hugo 2011; de Sherbinin et al. 2011). Migration as a response can be seen as either a failure of in-situ adaptation or as part of a portfolio of adaptation measures (Bardsley and Hugo 2010; de Sherbinin et al. 2011) which includes taking advantage of opportunities offered by cooler places (Tacoli 2009; Scheffran et al. 2012). Those who stay may be well-adapted and resilient. However, of particular concern to developing countries are those people who lack the resources to move away, that is that they are trapped (Black et al. 2011b). However, even successful in-situ adaptation to increasing temperatures might not prevent people from moving away (Sakdapolrak et al. 2014) because migration is rarely caused by a single factor alone but by many factors that collectively contribute to an individual’s decision to move (McLeman and Smit 2006; Black et al. 2011a). Interaction effects and the wider range of climatic effects on migration are not yet well understood (Carleton and Hsiang 2016).

In developing countries, the fact that people move, or are pushed, away because of climate change impacts is increasingly the subject of research (Bardsley and Hugo 2010; Massey et al. 2010; Gray and Mueller 2012a, 2012b; Warner and Afifi 2014; Ocello et al. 2015), with a few recent examples concentrating on heat stress (Mueller et al. 2014) and increasing temperatures (Bohra-Mishra et al. 2014; Gray and Wise 2016). There is much less research in this field from developed countries and is mostly limited to Indigenous people (Zander et al. 2013; King et al. 2014). For most people in developing countries, responding to climate change by migrating is impeded by shortages of economic resources and human capital (Black et al. 2011a) or inhibited for cultural reasons such as a strong attachment to traditional lands (Mortreux and Barnett 2009; Adger et al. 2013). Most people in developed economies such as Australia, in contrast, have few constraints on decisions about when and where to relocate to improve economic prosperity and wellbeing. As heat increases, it is therefore increasingly likely that people in developed economies will move to avoid it, regardless of their stage in life.

This chapter extends the work by Zander et al. (2016) on this topic using the same dataset: a cross-sectoral sample of people living in Australia between 18 and 65 years. This chapter explores peoples’ intention to move from their current place of residence to cooler places because of heat stress. It investigates determinants of the intention to move, the timeframe of moving and the geographical frame of their mobility.

Understanding how people adapt to heat is particularly important to Australia, a generally hot continent (see also Chap. 10). Australia’s climate has already warmed by 0.9 ℃ since 1910 and temperatures are projected to rise by 0.6–1.5 ℃ by 2030 compared with the climate of 1980–1999 (BoM 2014). As has happened globally (WMO and WHO 2015), both the duration and frequency of heatwaves had increased over the period 1971–2008 with the hottest days during heatwaves across most of Australia becoming even hotter (Perkins and Alexander 2013) and the chances of standalone hot days also being higher (Min et al. 2013; Perkins and Alexander 2013).

8.2 Data and Methods

8.2.1 Theory of Planned Behaviour

This chapter focuses on people’s intentions to move away from their current place of residence voluntarily because of heat. This intention reflects a willingness to change place of residence (de Jong 1999). Although this is not the same as actual moving (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Lu 1998; van Dalen and Henkens 2008; de Groot et al. 2011), it is a moderate to strong indicator of future movements, based on Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour (1991), that is particularly valued in the fields of human geography and psychology (Manski 1990; Sandu and de Jong 1996; van Dalen and Henkens 2008). Previous studies have shown a significant positive relationship between intentions and actual behaviour (van Dalen and Henkens 2008; Thissen et al. 2010).

8.2.2 Data Collection and Sampling

Data were collected through an online survey conducted in the last two weeks of May and the first two weeks of October 2014.Footnote 2 To carry out the survey, a research company (MyOpinions) we commissioned that has a continuously updated online panel of more than 300,000 verified respondents within Australia. Online surveys have many benefits over mail-out surveys and in-person interviews and are more cost-effective (Berrens et al. 2003; Dillman 2007; Fleming and Bowden 2009). Some studies have shown that results do not differ across survey modes (Lindhjem and Navrud 2011; Windle and Rolfe 2011). To avoid self-selection bias, not uncommon in online surveys, the topic of the survey was not made known when members of the panel were invited to participate. Respondents were paid $2 upon completion of the survey, which took between 13 and 15 min of their time.

In total, 9406 people from the MyOpinions panel were sampled (4913 in the first wave and 4493 in the second wave). The overall response rate was 20.5%, including a 3.3% drop-out rate. There were 1925 responses received in total, consisting of 847 and 1078 from each wave, respectively.

8.2.3 Questionnaire

The questionnaire comprised of three parts: (1) questions on general mobility including frequencies and reasons for past movements, (2) questions on intentions for future movements and whether heat would influence this movement, and questions about the timeframe of the movements and the intended destination, and (3) questions on respondents’ socio-demographic background, attitudes and climate change beliefs.

The first question within the second section was a general question about whether or not people had been feeling heat stressed in the previous 12 months. Those who denied this were assumed not to think about heat at all when deciding whether to move and were not included in the analysis on intentions to move because of heat.

8.2.4 Data Analysis

The data were tested for different factors likely to affect respondents’ probability of moving to cooler places because of heat using ANOVA. If the data required it, Tukey tests were then used for multiple comparisons of means.

8.3 Results and Discussion

Eighty-six of the 1925 responses obtained were largely incomplete and therefore omitted from further analysis. Out of the remaining 1839 respondents, 27% did not feel heat stressed in the year preceding the survey and were also not included in the analysis of movements because of heat stress. The final data set explored here, therefore, contains information of 1344 respondents.

8.3.1 Demographic Sample Characteristics

Slightly less than half of the respondents (48%) were female. The average age was 41 years (SD: 12.2), with a median of 41, which is slightly higher than the 37 median age at a national level (ABS 2015). One of the reasons for a higher median is that the survey was targeted to people over 18. Fifty-six per cent of respondents said they had children. Most respondents (72%) had tertiary education (Diploma: 35%, University: 37%) and most (96%) were in paid employment (Full-time: 57%; Part-time: 34%; Casual: 5%; Not in paid job: 4%). The average annual personal income was AUD 58,000 (SD: 76,000) with a median of AUD 50,000 which is very similar to the national median of working people between 18 and 65 (AUD 46,000; ABS 2012). In line with the national population distribution (ABS 2012), about 64% of the respondents were from the three most populated states (Victoria (VIC): 26%, New South Wales (NSW): 24% and Queensland (QLD): 16%) and proportionally fewer from the other states/territories (Western Australia (WA): 13%, South Australia (SA): 9%, Australian Capital Territory (ACT): 5%, Tasmania (TAS): 4%, Northern Territory (NT): 3%).

8.3.2 Past Movements and Their Reasons

About 18% of respondents were highly mobile, in that they usually moved once a year (3%) or every 2–3 years (15%) in the past. Almost half were moderately mobile (46%), moving once every five (20%) or ten years (26%) and about a third were relatively sedentary, having never moved either in their lives (11%) or within the last 15 years (25%).

Respondents’ mobility was correlated with age and family status. Younger people were more likely to be highly mobile (P < 0.001) which is consistent with the life cycle theory of migration which postulates that young people are most mobile, usually as they search for education and employment (Polachek and Horvath 1977; Coulter and Scott 2015). The average age of highly mobile people was 33.8 years, that of moderately mobile people 40.8 years and that of people with low mobility 44.5 years (Fig. 8.1). Those people with low and medium mobility were significantly more likely (P < 0.001) to have children (58% and 61% respectively) than those who were highly mobile (43%). Again, this can be attributed to respondents’ life cycles, stipulating that families with children are less mobile than singles or couples without children (Long 1972), particularly regarding long-distance movements (which is expected if one moves to escape the heat). The reasons behind this could be that the costs of moving increase as the number of persons living in a family rises and that the presence of additional members in the family means that more ties must be broken at the place of origin and established at the destination (Long 1972). Gender, income and work situation (workload and employee) did not have a significant impact on the degree of general mobility. The state from which people lived also had no significant impact on people’s general mobility.

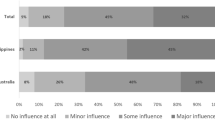

In line with migration/mobility theory (Clark and Withers 2007), employment was the most important reason for moving among respondents who had moved in the past (Fig. 8.2). Although the weather was the least important of the reasons for past movements, 41% of respondents listed it as having an important or very important influence in their decision to move in the past (this can include people moving to warmer as well as cooler climates).

8.3.3 Intention to Move Because of Heat

Almost 11% (N = 133) of respondents who said that they were stressed by heat intended to move because of this heat stress; the large remainder (89%; 1133) would not move for this reason. One result that stood out was that respondents living in the NT were about three times more likely to intend to move because of heat (36% versus the average of 11%; P < 0.001). This was not surprising given that most respondents from the NT live in Darwin, the capital, situated in the tropical Top End of Australia. Because of the high humidity, the perceived heat is particularly high for at least half the year (Goldi et al. 2015).

The intention to move was also affected by gender (P < 0.005), degree of perceived heat stress (P < 0.001) and general mobility (P < 0.001) (Table 8.1). A higher percentage of male respondents said they would move because of heat than female respondents (13% versus 8%; P < 0.01). Not surprising, the more heat stressed respondents said they felt, the more likely were they to intend to move because of heat stress with almost a third (28%) of those feeling very heat stressed intending to move.

Also not surprising was the result that highly mobile people (see previous section) were more likely to intend to move because of heat stress (21%). This is consistent with migration intention studies (de Jong et al. 1985). This can also mean that people see heat only as a factor in the mix of reasons why they would move, and they would probably move anyway after a certain time in the current location. On the other hand, it can mean that those who have never moved, are ‘trapped’ where they are, even if it becomes very hot, to the extent that it affects health. Often these people wish to stay because of tight connections (family, culture) to where they live, or because they have employment that they do not want to leave. In developing countries ‘trapped’ people do not have the resources to move away (Black et al. 2011b). In Australia, this might also be true for the very poor, noting that 13.3% of the population in Australia live below the poverty line (ACOSS 2016). This survey did not confirm that income was of concern when deciding to migrate because of heat stress. However, even though the income distribution of respondents resembled that of the general population, the sampling method may have excluded the very poorest people.

Other core demographic factors such as age, income, having children and workload did not have significant impacts on the intention to move because of heat. The conclusion that age did not affect moving intention was unexpected. Previous studies have shown that movement intentions (mainly international migration) were positively correlated with age (de Jong et al. 1985; de Groot et al. 2011). This means that heat can influence intentions to move regardless of a person’s stage in life. This can have consequences for service provision by altering normal movement patterns. For instance, if more middle-aged people in established careers move than would previously have been expected, this could leave a shortage of skills and labour in areas that experience more frequent uncomfortably hot weather.

8.3.4 Moving When?

Of those people who intend to move because of heat, most thought they might move in the distant future (33%), 17% in two to three years, 20% in about a year and 14% within the next three months (Table 8.2). A substantial proportion (13.5%) was in the process of moving at the time of the survey. Men stated significantly more often that they are already in the process of moving because of heat than women (19.3% versus 4%; P = 0.01). Women were significantly more likely to intend to move in the distant future (Table 8.2). Those of either gender who said they would move in the distant future were also older (P < 0.01) than those thinking of moving within the next three months (mean age 42.6 versus 34.3). Respondents with children were more likely to intend to move at later stages than those without children (P < 0.05).

Those already in the process of moving were more often stressed by heat than those intending to move later than within the next three months (P < 0.005). Those intending to move in the distant future exhibited lower general mobility than those who would move earlier (P < 0.005). Education, gender, income and location (their state) did not significantly explain the timeframe of potential heat related movements.

Those intending to move in the short-term (within a year, categories grouped) were significantly younger (P < 0.005), on average 37.2 years, than those planning movement in the long-term (42.8 years). This is again the highly transient population of young people. Of all men intending to move, more than half (58%) would do so in the short-term, while only 36% of those women intending to move would do so in the short-term (P < 0.01).

8.3.5 Moving from Where to Where?

More than a third (38%) of those wanting to move because of heat stress did not know where they would move to. Most people (91%) would move within Australia with the remaining 9% intending to move overseas. Significantly, more women intended to move overseas than men (16% versus 5%; P < 0.05).

Only 9% would move within their state of origin, most (91%) would change states. Almost 20% would move to TAS (Table 8.3), particularly from NSW (31%) and VIC (19%). TAS was the only state that would receive more people than it would lose, which was expected given its cold climate.

Nobody would move to the NT or SA (Table 8.3), with a particularly high proportion of those from the NT (36%) intending to move because of heat stress (Table 8.1); this proportion was only about 9% in SA. Besides the NT, many of the respondents intending to move were from QLD (ratio: origin (%)/sample distribution % = 1.24; Table 8.3) and NSW (ratio = 1.06). This was not surprising, given that parts of the NT and QLD lie in the tropical humid north, and given that a large proportion of respondents from the NT stated an intention to move. It was surprising, however, that so few people from SA intended to move because of heat, given that Adelaide and surroundings saw record temperatures and increasing frequencies of heat waves in the last few years (Steffen et al. 2014) with many people suffering (Xiang et al. 2014; Hatvani-Kovacs et al. 2016; Zander et al. 2017).

Those currently in the NT would move mainly to QLD (29%), WA (21%) or NSW (14%). Those originating in SA mostly did not know their potential destination (40%) or stated TAS (30%), QLD (20%) or VIC (10%) as destinations.

8.4 Conclusion

Our results provide one, out of several accounts, of the general population in a developed economy intending to relocate because of climatic heat stress. So far most research on migration as a response to climate change is from developing countries, or, if in developed countries, then in the context of Indigenous people. Because people in Australia are free to move if financial resources permit, this research applied Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour to investigate peoples’ intention to move away to cooler places. Results of an Australian-wide online survey with about 1900 respondents showed that 11% of those respondents who said that they were stressed by heat intended to move away because they felt heat stressed in their current place of residence. As expected, people who have been highly mobile in the past were more likely to intend to move because of heat, while age did not affect the intention to move because of heat stress. Men were also more likely to intend to move because of heat stress. Most heat-stressed men intended to move in within the next three months while most women (42% of those intending to move) would do so in the distant future. Younger respondents are more likely to move in a short-time frame, many of those already in the process of moving. People living in the NT, notably from the tropical (hot and humid) Top End of Australia, were three times more likely to move because of heat stress. Although slightly more than a third of respondents intending to move did not know where to, among those who knew, the preferred destination was Tasmania which has one of the lowest mean temperatures in Australia. Many people (38%) were unsure about a potential destination and Tasmania was a preferred destination for those who were not.

Notes

- 1.

Several definitions of the term heat wave exist within the international meteorological community. The IPCC defines a heat wave as a ‘period of abnormally and uncomfortably hot weather’ (IPCC 2014).

- 2.

The surveys were staggered into two waves to reduce the chance of surveying during (or soon after) particularly hot periods, choosing late May and early October as being times when exceptional heat would be unlikely. The other reason for conducting the survey in two sessions was to ensure that to the demographics of both samples were representative of Australian society and that results could be replicated.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2012) Census of population and housing - 2011. Data generated using ABS Table Builder. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2015). 3101.0 - Australian Demographic Statistics, Jun 2015. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/featurearticlesbyCatalogue/7A40A407211F35F4CA257A2200120EAA?OpenDocument [accessed 5 December 2016].

ACOSS (Australian Council of Social Service) (2016) Poverty in Australia 2016. Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney. https://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Poverty-in-Australia-2016.pdf [accessed 5 December 2016].

Adger WN, Barnett J, Brown K, Marshall N, O’Brien K (2013) Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nature Climate Change 3: 112–117.

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50:179–211.

Bardsley DK, Hugo GJ (2010) Migration and climate change: examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making. Population and Environment 32: 238–262.

Barnett G, Beaty RM, Meyers J, Chen D, McFallan S (2015) Pathways for adaptation of low-income housing to extreme heat. In: Palutikof JP, Boulter SL, Barnett J, Rissik D (eds) Applied studies in climate adaptation. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 364–371.

Berrens R, Bohara A, Jenkins-Smith H, Silva C, Weimer D (2003) The advent of internet surveys for political research: A comparison of telephone and internet samples. Political Analysis 11: 1–22.

Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, Thomas D (2011a) The effect of environmental change on human migration. Global Environmental Change 21: S3–S11.

Black R, Bennett SRG, Thomas SM, Beddington JR (2011b) Migration as adaptation. Nature 478: 447–449.

Bohra-Mishra P, Oppenheimer M, Hsiang SM (2014) Nonlinear permanent migration response to climatic variations but minimal response to disasters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111: 9780–9785.

Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) (2014) State of the climate 2014. BoM and CSIRO, Canberra.

Carleton TA, Hsiang SM (2016) Social and economic impacts of climate. Science 353: aad9837.

Chen D, Wang X, Thatcher M, Barnett G, Kachenko A, Prince R (2014) Urban vegetation for reducing heat related mortality. Environmental Pollution 192: 275–284.

Clark WAV, Withers SD (2007) Family migration and mobility sequences in the United States: spatial mobility in the context of the life course. Demographic Research 17: 591–622.

Coumou D, Robinson A, Rahmstorf S (2013) Global increase in record-breaking monthly mean temperatures. Climatic Change 118: 771–782.

Coulter R, Scott J (2015) What motivates residential mobility? Re-examining self-reported reasons for desiring and making residential moves. Population Space and Place 21: 354–371.

de Groot C, Mulder CH, Das M, Manting D (2011) Life events and the gap between intention to move and actual mobility. Environmental Planning A 43: 48–66.

de Jong G, Root BD, Gardner RW, Fawcett JT, Abad RG (1985) Migration intentions and behaviour: decision making in a rural Philippine province. Population and Environment 8: 41–62.

de Jong GF (1999) Choice process in migration behaviour. In: Pandit K, Withers S (eds) Migration and restructuring in the United Sates. Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, pp. 273–293.

de Sherbinin A, Castro M, Gemenne F, Cernea MM, Adamo S, Fearnside PM, et al. (2011) Preparing for resettlement associated with climate change. Science 28: 456–457.

Dillman DA (2007) Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method - 2007 update with new internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide. Wiley, New York.

Fang J, Li M, Shi P (2015) Mapping heat wave risk of the world. In: Shi P, Kasperson R (Eds.), World atlas of natural disaster risk. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 69–102.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley, Reading.

Fleming C, Bowden M (2009) Web-based surveys as an alternative to traditional mail methods. Journal of Environmental Management 90: 284–292.

Goldi J, Sherwood SC, Green D, Alexander L (2015) Temperature and humidity effects on hospital morbidity in Darwin, Australia. Annals of Global Health 81: 333–341.

Gray C, Mueller V (2012a) Drought and population mobility in rural Ethiopia. World Development 40: 134–145.

Gray CL, Mueller V (2012b) Natural disasters and population mobility in Bangladesh. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 6000–6005.

Gray C, Wise E (2016) Country-specific effects of climate variability on human migration. Climatic Change 135: 555–568.

Hatvani-Kovacs G, Belusko M, Skinner N, Pockett J, Boland J (2016) Heat stress risk and resilience in the urban environment. Sustainable Cities and Society 26: 278–288.

Hugo G (2011) Future demographic change and its interactions with migration and climate change. Global Environmental Change 21: S21–S33.

IPCC (2014) Annex II: Glossary. In: Mach KJ, Planton S, Stechow C von (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva, pp. 117–130.

King D, Bird D, Haynes K, Boon H, Cottrell A, Millar J, Okada T, Box P, Keogh D, Thomas M (2014) Voluntary relocation as an adaptation strategy to extreme weather events. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 8: 83–90.

Lindhjem H, Navrud S (2011) Are Internet surveys an alternative to face-to-face interviews in contingent valuation? Ecological Economics 70: 1628–1637.

Long LH (1972) The influence of number and ages of children on residential mobility. Demography 9: 371–382.

Lu M (1998) Analyzing migration decision making: relationships between residential satisfaction, mobility intentions, and moving behavior. Environmental Planning A 30: 1473–1495.

Manski CF (1990) The use of intentions data to predict behavior: a best-case analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 85: 934–940.

Massey DS, Axinn WG, Ghimire DJ (2010) Environmental change and out-migration: evidence from Nepal. Population and Environment 32: 109–136.

McLeman R, Smit B (2006) Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Climatic Change 76: 31–53.

Min S-K, Cai W, Whetton P (2013) Influence of climate variability on seasonal extremes over Australia. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 118: 643–654.

Mortreux C, Barnett J (2009) Climate change, migration and adaptation in Funafuti, Tuvalu. Global Environmental Change 19: 105–112.

Mueller V, Gray C, Kosec K (2014) Heat stress increases long-term human migration in rural Pakistan. Nature Climate Change 4: 182–185.

Ocello C, Petrucci A, Testa M, Vignoli D (2015) Environmental aspects of internal migration in Tanzania. Population and Environment 37: 99–108.

Parsons K (2003) Human thermal environment. the effects of hot, moderate and cold temperatures on human health, comfort and performance. 2nd Ed. CRC Press, New York.

Perkins SE, Alexander LV, Nairn JR (2012) Increasing frequency, intensity and duration of observed global heatwaves and warm spells. Geophysical Research Letters 39: L20714.

Perkins S, Alexander L (2013) On the measurement of heat waves. Journal of Climate 26: 4500–4517.

Polachek S, Horvath F (1977) A life cycle approach to migration: analysis of the perspicacious peregrinator. In: Ehrenberg R (Ed), Research in labor economics. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Robine J-M, Cheung SLK, Le Roy S, Van Oyen H, Griffiths C, Michel J-P, et al. (2008) Death toll exceeded 70,000 in Europe during the summer of 2003. Comptes Rendus Biologies 331: 171–178.

Sakdapolrak P, Promburom P, Reif A (2014) Why successful in-situ adaptation with environmental stress does not prevent people from migrating? Empirical evidence from Northern Thailand. Climate and Development 6: 38–45.

Sandu D, de Jong GF (1996) Migration in market and democracy transition: migration intentions and behaviour in Romania. Population Research and Policy Review 15: 437–457.

Scheffran J, Marmer E, Sow P (2012) Migration as a contribution to resilience and innovation in climate adaptation: Social networks and co-development in Northwest Africa. Applied Geography 33: 119–127.

Solecki WD, Rosenzweig C, Parshall L, Pope G, Clark M, Cox J, Wiencke M (2005) Mitigation of the heat island effect in urban New Jersey. Environmental Hazards 6: 39–49..

Steffen W, Hughes L, Pearce A (2014) Heatwaves: hotter, longer, more often. Public Climate Council of Australia Limited. https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/uploads/7be174fe8c32ee1f3632d44e2cef501a.pdf [accessed 5 December 2016].

Tacoli C (2009) Crisis or adaptation? Migration and climate change in a context of high mobility. Environment and Urbanization 21: 513–525.

Thissen F, Fortuijn JD, Strijker D, Haartsen T (2010) Migration intentions of rural youth in the Westhoek, Flanders, Belgium and the Veenkoloniën, The Netherlands. Journal of Rural Studies 26: 428–436.

van Dalen HP, Henkens K (2008) Emigration intentions: mere words or true plans? explaining international migration intentions and behavior. CentER Discussion Paper 2008–60, Center for Economic Research, Tilburg University.

Warner K, Afifi T (2014) Where the rain falls: evidence from 8 countries on how vulnerable households use migration to manage the risk of rainfall variability and food insecurity. Climate and Development 6: 1–17.

Windle J, Rolfe J (2011) Comparing responses from internet and paper-based collection methods in more complex stated preference environmental valuation surveys. Economic Analysis and Policy 41: 83–97.

WOE, WHO (2015) Heatwaves and health: guidance on warning-system development. World Meteorological Organization and World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/globalchange/publications/heatwaves-health-guidance/en [accessed 5 December 2016].

Xiang J, Bi P, Pisaniello D, Hansen A (2014) The impact of heatwaves on workers׳ health and safety in Adelaide, South Australia. Environmental Research 133: 90–95.

Zander KK, Petheram L, Garnett ST (2013) Stay or leave? - Potential climate change adaptation strategies among Aboriginal people in coastal communities in northern Australia. Natural Hazards 67: 591–609.

Zander KK, Botzen WJW, Oppermann E, Kjellstrom T, Garnett ST (2015) Heat stress causes substantial labour productivity loss in Australia. Nature Climate Change 5: 647–651.

Zander KK, Surjan A, Garnett ST (2016) Exploring the effect of heat on stated intentions to move. Climatic Change 138: 297–308.

Zander KK, Moss SA, Garnett ST (2017) Drivers of heat stress susceptibility in the Australian labour force. Environmental Research 152: 272–279.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zander, K.K., Richerzhagen, C., Garnett, S.T. (2021). Migration as a Potential Heat Stress Adaptation Strategy in Australia. In: Karácsonyi, D., Taylor, A., Bird, D. (eds) The Demography of Disasters. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49920-4_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49920-4_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-49919-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-49920-4

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)