Abstract

This chapter explores how spiritual aspects of care are being documented within the UK with a specific focus on healthcare primarily in the nursing and chaplaincy professions. This has not been an easy undertaking given the lack of a standardised approach, the changing and challenging landscape of healthcare in the UK and the conflicting terminology used when trying to assess, capture and record encounters, interactions and conversations with patients and their carers about their spiritual needs. The authors draw upon their own research and informal enquiries with chaplains from across England, Scotland and Wales, demonstrating that there is a wide range and variation in practice. The authors conclude that there is no standardised means of assessing and documenting spiritual needs and care in the UK and that this is unlikely to change until the many complex challenges outlined are addressed both politically and professionally.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

We were asked if we would provide a United Kingdom (UK) perspective on charting or documenting of spiritual care. This has been no straightforward task. We identified some of the dilemmas and challenges in assessing and documenting back in 2002 (McSherry and Ross 2002) and 2010 (McSherry and Ross 2010). We were hopeful that things may have changed; however, instead we found the situation has become even more complex. This is largely because of the number of people with responsibility for spiritual care, lack of clarity surrounding their roles and responsibilities in providing spiritual care and in documenting what they do, and conflicting terminology. Added to this the landscape of healthcare policy and practice is constantly changing meaning that healthcare staff have to be incredibly adaptable as their roles and responsibilities respond to these changes. An increasing awareness of Information Governance and concerns about protecting patient confidentiality means that staff (particularly chaplains) are cagy about what they are willing to share publicly in relation to their practice. In this chapter, we explore this complex situation in more detail. We start by giving a brief overview of the place of spirituality in the UK National Health Service (NHS) . We then look at who provides spiritual care, identifying the challenges they face in so doing. The additional challenge of conflicting terminology is explored before examples of how spiritual needs and care are charted/documented are provided.

1 Spirituality Within the UK National Health Service (NHS): A Core Concept

As early as the fifth century BC, Hippocrates recognised the importance of both the body and the soul in health. Historically, in Western medicine, the body and soul were inseparable with the sick being cared for as whole beings, body, mind and spirit. An example is the Knights of St. John, who set up a hospital to care holistically for sick pilgrims in eleventh-century Jerusalem. It is now known as the St John Ambulance, the UK’s leading first-aid charity. Focus on care of the whole person continued to be at the heart of the newly formed NHS in 1948, where hospital chaplains were employed as specialist spiritual care providers. They are still employed in this capacity today. The NHS Constitution puts ‘the patient […] at the heart of everything the NHS does’ (Department of Health & Social Care 2015, 3). Spiritual needs and care are important to people when faced with life’s challenges such as illness (Selman et al. 2018). Healthcare delivery is to be evidence driven (www.nice.org.uk/guidance [n.d.]), and evidence shows that spiritual wellbeing is positively associated with quality of life and fosters coping mechanisms (Koenig et al. 2012; Steinhauser et al. 2017). Spirituality, therefore, features in healthcare policy at world level (e.g. WHO 2002), within Europe (especially in palliative care, e.g. EAPC (www.eapcnet.eu/eapc-groups/task-forces/spiritual-care [n.d.])) and within the UK (e.g. Welsh Government 2015; NICE no date).

2 Who Provides Spiritual Care?

Spiritual care is provided by ‘healthcare staff, by carers, families and other patients’, whilst ‘chaplains are the specialist spiritual care providers’ (UKBHC 2017, 2).

2.1 Healthcare Staff

All healthcare staff can provide spiritual care. Nurses, however, are in a unique position as they are the only healthcare professionals who are with the patient 24/7. Nurses act as gatekeepers to other services, including chaplaincy, and they advocate on the patient’s behalf. Spiritual care is part of their holistic caring role (ICN 2012), and they are expected to be competent in assessing spiritual needs and in planning, implementing and evaluating spiritual care (NMC 2018). However, they face a number of challenges.

2.1.1 What and How to Assess and Document?

Nurses are expected to document the care they give and the decisions they make, but there is considerable variation across the UK in how this is achieved in practice. In Wales, the need for a unified approach to assessment in nursing has been identified, and a single streamlined assessment document has been developed and is currently being piloted in acute hospital settings across the country (e-nursing project). Assessment of spiritual care needs is part of this document.

Although spiritual care is part of the nurse’s role which nurses are required to document, evidence suggests that this may not happen routinely. For example, a survey conducted by the Royal College of Nursing of the UK in 2010 found that only 3 out of 139 (2.2%) respondents said they used a formal spiritual assessment tool; a similar study in Australia reported 18 out of 191 respondents (26%) using a formal tool (Austin et al. 2017). Instead, respondents said they identified spiritual needs informally by listening and observing.

2.1.2 More Education?

A growing body of international evidence suggests that nurses feel unprepared for spiritual care and want further education to enable them to be more confident and competent in this aspect of their role (RCN 2010). Lack of education, first identified by Ross (1994), appears to be the greatest barrier to nurses assessing/screening for spiritual needs and recording spiritual care. McSherry reported a similar finding in 1997; 71.8% (n = 394) of nurses in his sample said they felt unprepared and wanted further education.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, nurse education in the UK underwent a major restructuring, shifting from colleges and schools of health into the higher education sector with a change of emphasis from the apprentice-style training to a greater focus on academic study. Around the same time, there was an explosion of interest in the spiritual dimension of healthcare. One would have thought that these two significant changes would have resulted in nurses feeling more prepared for spiritual care; however it seems that little has changed. A survey conducted by the RCN in 2010 reported 79.3% of respondents still feeling unprepared for this aspect of their practice, and 79.9% calling for further education. The RCN responded by producing guidance in the form of a pocket guide and an on-line educational resource (RCN 2011). The EPICC Project 2016–2019 (www.epicc-project.eu) is the most significant response to date. Over three years, 31 nurse/midwifery educators from 21 countries co-produced a set of spiritual care competencies which are shaping nurse/midwifery undergraduate curricula across Europe. A toolkit provides teaching and learning activities to enhance competency development. In some countries, for example, Wales, the competencies are being used to shape curricula of other healthcare professions (e.g. professions allied to medicine) and ancillary staff. It will be interesting to see if there is any change in nurses’/midwives’ preparedness for spiritual assessment and care should the RCN survey be repeated when the first graduates from these new programmes become qualified nurses and midwives in five or six years’ time.

2.2 Chaplains/Spiritual Care Givers

Healthcare chaplains are the specialist spiritual care providers in the NHS in the UK. Traditionally they were ministers of religion from the Christian faith who were paid for by the NHS but managed through their churches. Hospital chapels were built where church services and rituals such as baptism and communion were conducted. However, societal changes in the last two decades, whereby society has become increasingly secular and multi-cultural, have meant that chaplaincy has had to evolve to meet the changing needs of the people it serves. Scottish health policy introduced in 2002 (HDL 76) saw the remit of chaplains broaden to include care of ʻspiritual’ as well as ʻreligious’ needs of people of all faiths (of which there are now many) and no faith, and this broader remit has filtered throughout the UK. Recent years have seen even greater role change as chaplains respond to the needs of the people and organisations they serve. Roles have diversified to include, for example, specialist roles, interdisciplinary team working, training and education, training and management of volunteers, research and evaluation including audits and increasing engagement with stakeholder groups including third sector organisations. This means that chaplains are working in increasingly varied ways in increasingly diverse settings. These changes have presented a number of challenges for chaplains/spiritual care givers.

2.2.1 What to Call the Service?

Many hospitals have changed their name from ʻchaplaincy department’ to ʻdepartment of spiritual care’ to reflect the wider remit of the service they provide.

2.2.2 Who Chaplains Are?

The requirement to be a minister of religion may no longer be appropriate in a society which is becoming increasingly secular and where religious practice is in decline. Some hospitals now employ humanist or ʻsecular’ chaplains to lead their departments. Many larger hospitals will have teams made up of different faith leaders to represent the multifaith profile of the communities they serve.

2.2.3 What Qualifications Are Needed to Be a Chaplain?

If it is no longer necessary to be a minister of religion, then what training is needed, and how does this differ from that, say, of a psychologist or a psychotherapist? There is currently no common training programme to become a chaplain, although in Scotland a new postgraduate qualification in spiritual care is in development. Chaplaincy volunteers, who may have no qualifications, are heavily relied on in many hospitals, raising questions about the appropriateness of this and the training they may need.

2.2.4 Who Should Be Paying for a Service?

As chaplaincy offers religious support within its remit in a society where religious practice is in decline, some question whether the NHS should continue to pay for it. The National Secular Society, for example, wants funding for hospital chaplaincy to stop and be reinvested in other ways, such as for the purchase of equipment.

2.2.5 Whether Chaplains Are Professionals and Who They Are Accountable to?

Chaplains work alongside other professional groups such as doctors, nurses and professions allied to medicine. All these professions have a recognised education programme, a code of conduct and a regulatory body which sets criteria and standards that must be reached and maintained to ensure safe practice. There are no such mandatory requirements for hospital chaplains.

Since 2007, all whole time chaplains in Scotland became employees of the NHS rather than the church. This became common practice also in the UK. Chaplains have, therefore, come under greater scrutiny regarding the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, safety and quality of their practice. In response to this change in governance, a number of associations were set up to which chaplains could belong, some according to country, others by specialty (Table 1). However, the UK Board of Healthcare Chaplaincy (UKBHC) is the only body offering professional registration for chaplains. Accredited by the Professional Standards Agency, the UKBHC provides a code of conduct, standards, competencies and capabilities for chaplains as well as a fitness to practice process. Although registration is currently voluntary, the intention is that this will become mandatory in the near future. Table 2 shows the chaplaincy standards, competencies and capabilities that currently exist in the UK, although those provided by the UKBHC (2009) are generally regarded as the most up to date. Additionally, chaplaincy guidelines have been produced in England (Swift 2015).

3 In Pursuit of Examples of Charting/Recording/Documenting/Assessing in the UK

It was against this complex backdrop that we sought to identify examples of charting/recording/documenting/assessing of spiritual care in the UK, and our next challenge emerged, that of conflicting terminology.

3.1 Conflicting Terminology

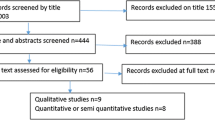

A simple search of the CINHAL full-text database was undertaken in autumn 2018 using a range of search terms as follows:

-

ʻcharting and spirit*’ yielded a total of 19 records (reduced to 1 when ʻand’ was removed). Most pertained to charting of spiritual care within the fields of chaplaincy and parish nursing.

-

ʻdocumenting and spirit*’ yielded 39 results (reduced to 9 when ʻand’ was removed), but the majority were unrelated to the documentation of spiritual care as defined for this book and were from a broad spectrum of disciplines.

-

ʻrecording and spirit*’ yielded 59 records (reduced to 8 when ʻand’ was removed), but again most were not directly relevant to the topic of this book.

-

ʻcare plan and spirit*’ yielded the highest return, 259 results. Concrete examples of tools were not given in these articles.

This simple search highlights issues around the use of language and how the terms ʻcharting/documenting/recording’ may be interpreted differently across healthcare professions, countries and cultures when applied to meeting the spiritual, religious or pastoral needs of a person.

This brief analysis highlights that there is no internationally recognised universal term for charting/recording/documenting of spiritual care. In the UK, the word ʻcharting’ would tend to relate to the recording of a patient’s vital signs or fluid balance on a chart. ʻRecords’ could apply to all documents that pertain to a patient whether in paper or electronic formats. The term ʻcare plan’ is well recognised in nursing and achieved the greatest number of hits in the above search, picking up articles relating to the recording of spiritual issues by nurses.

This search highlights that different professions are involved in spiritual care and that terminology may be discipline specific. We now give examples of charting/documenting/assessing/recording from nursing and chaplaincy.

3.2 Examples of Charting/Documenting/Recording/Assessing by Nurses in the UK

We have already identified that professional groups, such as nurses, are required by their regulatory body to keep a record of what they do (NMC 2015) and that the actual format of that record will vary greatly. What is less clear, however, is what exactly nurses record about spiritual needs and care. We provide three examples.

3.2.1 Care Planning in Mental Health in England

Walsh et al. (2013) conducted a comparative study evaluating the efficacy with which care plans capture and make use of data on the spiritual and religious concerns of mental health service users in one UK Health and Social Care Trust. The findings reveal that (a) the importance that many service users accorded to spirituality and religion was not reflected in the electronic records, (b) that some information was wrong or wrongly nuanced when compared with the patient’s self-description and (c) that service users themselves were often mistaken regarding the type and quality of information held on record. Walsh et al. (2013, 161) conclude that this may be because ‘the majority of Care Coordinators are unable to see the relevance of spiritual or religious concerns, or feel incompetent to record them faithfully’.

3.2.2 Care Planning in Mental Health in Wales

In Wales, it is a legal requirement that people being treated for mental health problems have a Care and Treatment Plan (CTP). There are eight domains within the CTP covering people’s medical needs, financial needs, accommodation needs, etc. Domain 7 asks about a person’s ʻsocial, cultural and spiritual’ needs. In 2016 we conducted a pilot study in three of the seven Health Boards in Wales to find out what was written in Domain 7 of the CTP and to explore staff’s experience of completing it (Fothergill 2018).

What was written in the CTP? Assessments were mainly carried out by care co-ordinators who were usually mental health nurses. We typed out verbatim what was written in Domain 7 from 150 CTPs (a mix of community and hospital records, 50 from each Health Board). Two researchers independently conducted a content analysis identifying 11 themes which were subsequently reduced to 8 (small themes were merged). The key findings are shown in Table 3.

Mainly social needs were recorded, e.g. involving people in meaningful activities (memory books, hobbies, etc.) and maintaining social connections with family and staff. The spiritual needs recorded were mainly of a religious nature, for example, facilitating attendance at religious services and listening to religious music.

Staff’s experience of completing the CTP: We ran two focus groups in 2016, one with seven nurses and the other with four nurses who were care co-ordinators, experienced and newly qualified mental health nurses from both hospital and community. Sessions were tape recorded and transcribed and themes were identified. The staff stated that Domain 7 was the least frequently completed and that they found it the most difficult to complete. They found spiritual needs difficult to articulate and therefore difficult to assess, and they had not had any training which they felt would be beneficial. When we encouragingly talked about spiritual care, they saw it as something broader than religion; it was about identifying what gives a person meaning/peace/contentment, what puts a smile on someone’s face or what gives hope, but they did not document this as spiritual care.

3.2.3 A Spiritual Assessment Model for Nurses

Nurses are key to patients having their spiritual needs assessed, but evidence suggests they feel unprepared for this part of their role and often see it as an extra task on top of an already heavy workload. As a result, patients are at risk of their spiritual needs being ignored. We, therefore, developed a pragmatic spiritual assessment model, the ʻ2 question spiritual assessment model’ (2Q-SAM; see Fig. 1 and Ross and McSherry 2018), to help nurses to undertake a spiritual assessment that may not require any extra time. Instead, the model encourages nurses to give care that is inherently ʻspiritual’ because it addresses what is most important to the patient at any point in time (integrated rather than an ʻadd-on’). It may even save time (addressing the prudent healthcare agenda), as time will not be wasted on unnecessary tasks. The two questions are ʻwhat’s most important to you?’ and ʻhow can I help?’. Additional benefits are that care is co-produced, person-centred and needs led. The model is currently being field tested.

The ʻ2 question spiritual assessment model’ (2Q-SAM) (Reprinted from Ross, L., McSherry, W. (2018). Two questions that ensure person-centred spiritual care. Nursing Standard [Internet]. https://rcni.com/nursing-standard/features/two-questions-ensure-person-centred-spiritual-care-137261, with permission from University of South Wales. Copyright © 2018 University of South Wales. All rights reserved)

4 Examples of Charting/Documenting/Recording/Assessing by Chaplains in the UK

We struggled to find any concrete examples of how chaplains record what they do from on-line searching. This led us to question whether there is any such requirement for chaplains to record what they do in the UK. We did this by:

-

(1)

Conducting a key word search (search terms ʻchart’, ʻdocument’ and ʻrecord’) of four documents listed in Table 4, one each from the UK, Scotland, England and Wales

-

(2)

Contacting chaplains personally known to us, in Scotland, England and Wales to ask for examples from their practice

4.1 Conducting a Key Word Search

Table 4 shows the results of the search.

It is clear from Table 4 that chaplains are required to keep some sort of record of what they do but exactly what information should be included, and the format for that is not stipulated.

4.2 Contact with Chaplains

Chaplains from one country, who were together for another purpose, were asked about examples of how they document what they do, but they were reluctant to share this; that door was firmly closed.

One lead chaplain from another country pointed out that, whilst there is a requirement to keep a record, any attempt to develop a standard format would be problematic because of the extent of local variation in chaplains’ practice. In his organisation chaplains record their visits directly in the patient’s electronic record, alongside that of other healthcare providers (HCP) in line with a protocol established following an investigation.

A lead chaplain from another country said that chaplains have each developed their own personal ways of recording what they do, producing their own forms, systems or spreadsheet to track contacts and visits.

We approached five other chaplains personally known to us and had responses from four of these. They were willing to share how they record what they do, and three were willing for their documents to appear in this book. All wished to remain anonymous. The overwhelming concern seemed to relate to Information Governance, particularly in relation to breaching patient confidentiality. Additionally, many chaplains simply were not convinced of the need to record anything.

4.2.1 An Example from a Chaplain in Scotland

The Health Board has one lead chaplain, a chaplaincy co-ordinator and a number of community volunteers. No assessment tools are used. Rather, patients identified on the hospital computerised system as belonging to a particular religion, or wishing to see a chaplain, are visited. The conversation between patients and the chaplain dictates what care is given. The chaplain keeps a record of visits in a notebook. This is not generally shared with any other members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT), except in the palliative care unit at whose MDT meetings the Chaplain has traditionally been welcomed.

4.2.2 An Example from a Chaplain in Wales

The Health Board has several hospitals, and each one has its own approach to documenting. In one hospital, when a referral is received, a chaplain will visit a patient, and the conversation will be guided by the outline in screenshot 1. Relevant information will be recorded in the Chaplaincy Patient Care Plan (screenshot 2) using ʻThe Graph’ (screenshot 3) to prioritise patients’ needs (Figs. 2, 3 and 4).

4.2.3 An Example from a Chaplain in Wales

This Health Board has four hospitals, and the chaplains in one hospital developed a tool for recording their contact with patients. It records how the referral was made, what was done (whether spiritual or pastoral care, Holy Communion or prayer was given) and whether another visit is planned and leaves space for further comment (screenshot 4) (Fig. 5).

4.2.4 An Example from a Chaplain in England

It is clear when talking to several lead chaplains in England that they are using a range of different methods to record and capture key information regarding referrals and contact with patients and their carers. Table 5 shows the types of information being recorded in one NHS Trust in various ways including notebooks, Excel spreadsheets and other electronic recording systems.

5 Conclusion

We have been unable to identify any nationally recognised approaches by chaplains to assess and document spiritual needs and care in the UK. Informal enquiries with some chaplains in England, Scotland and Wales indicate that formal approaches to assessment, such as the use of tools, are not generally used. Instead, spiritual needs are assessed informally through conversation with the patient. If and how information obtained from these conversations is documented or shared (and with whom) is also difficult to determine. It seems that some chaplains do not document or share at all, whilst others have developed their own ways of keeping records of visits within their own teams. Outside of palliative care, chaplains may not be included in MDT meetings. In many places they are unable to access or contribute to patients’ medical notes, despite supposedly being ‘expected to take their place as members of the multiprofessional healthcare team’ (UKBHC 2017, 2). The audit of chaplaincy services appears to be equally piecemeal.

The assessment of spiritual needs and documentation of spiritual care by nurses is equally vague. Whilst admission forms generally ask about a person’s ‘religion’, this is frequently left blank. If and how spiritual care needs are included within care plans is also unclear. The examples we have provided give some insight into how this is being done in some mental health settings in Wales. A PhD study starting shortly will engage key stakeholders in developing unified spiritual assessment and documentation processes that are fit for purpose across Wales.

We conclude that there is no standardised means of assessing and documenting spiritual needs and care in the UK and that this is unlikely to become a reality until the many complex challenges we have outlined in this chapter are addressed. A new study on the professionalisation of chaplains across the UK, if fully funded, may make a start on addressing some of these complexities.

References

Association of Hospice and Palliative Care Chaplains. 2006. Standards for Hospice and Palliative Care Chaplaincy.

Austin, P., R. MacLeod, P. Siddall, W. McSherry, and R. Egan. 2017. Spiritual care training is needed for clinical and non-clinical staff to manage patients’ spiritual needs. Journal for the Study of Spirituality 7 (1): 50–53.

Department of Health and Social Care. 2015. The NHS constitution. London: Crown.

European Association for Palliative Care. n.d. EAPC task force on spiritual care in palliative care. https://www.eapcnet.eu/eapc-groups/task-forces/spiritual-care. Accessed 20 Dec 2018.

Fothergill, A. 2018. Exploring how the spiritual needs of dementia patients are addressed within Care and Treatment Plans (CTPs) in three Health Boards (HBs) in Wales, Report. Pontypridd: University of South Wales.

International Council of Nurses (= ICN). 2012. Code of ethics for nurses. Geneva: ICN.

Koenig, H., D. King, and V. Carson. 2012. Handbook of religion and health. New York: OUP.

McSherry, W. 1997. A descriptive survey of nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. Unpublished MPhil thesis. Hull: The University of Hull.

McSherry, W., and L. Ross. 2002. Dilemmas of spiritual assessment: Considerations for nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 38 (5): 479–488.

———. 2010. Spiritual assessment in healthcare practice. Keswick: M&K Publishing.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2011. End of life care for adults: Quality Standard 13. Available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs13/documents/qs13-end-of-life-care-for-adults-quality-standard-large-print-version2. Accessed 27 Mar 2019.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (= NICE). n.d. www.nice.org.uk/guidance. Accessed 19 Mar 2019.

NHS Education Scotland. 2007. Standards for NHS Scotland Chaplaincy Services 2007. Edinburgh: NES.

NHS HDL 76. 2002. Available at www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/mels/hdl2002_76.pdf.Accessed 25 March 2019.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. 2018. Standards of proficiency for registered nurses. London: NMC.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (= NMC). 2015. The code. London: NMC.

Ross, L.A. 1994. Spiritual aspects of nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 19: 439–447.

Ross L., and W. McSherry. 2018. Two questions that ensure person-centred spiritual care. Available at: rcni.com/nursing-standard/features/two-questions-ensure-person-centred-spiritual-care-137261. Accessed 27 March 2019.

Royal College of Nursing. 2011. Spirituality in nursing: A pocket guide. London: RCN.

Royal College of Nursing (= RCN). 2010. Spirituality survey 2010. Available at www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-003861. Accessed 5 Dec 2018.

Selman, L., L. Brighton, S. Sinclair, I. Karvinen, R. Egan, P. Speck, et al. 2018. Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliative Medicine 32 (1): 216–230.

Steinhauser, K.E., G. Fitchett, G.F. Handzo, K.S. Johnson, H.G. Koenig, K.I. Pargament, et al. 2017. State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research part I: Definitions, measurement, and outcomes. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 54 (3): 428–440.

Swift C. 2015. NHS chaplaincy guidelines 2015: Promoting excellence in pastoral, spiritual and religious care. Available at hcfbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/nhs-chaplaincy-guidelines-2015.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2019.

UK Board of Healthcare Chaplaincy. 2017. Spiritual and religious care capabilities and competences for healthcare chaplains bands (or levels) 5, 6, 7 & 8. Cambridge: UKBHC.

UK Board of Healthcare Chaplaincy (= UKBHC). 2009. Standards for healthcare chaplaincy services. Cambridge: UKBHC.

Walsh, J., W. McSherry, and P. Kevern. 2013. The representation of service users’ religious and spiritual concerns in care plans. Journal of Public Mental Health 12 (3): 153–164.

Welsh Government. 2010. Standards for spiritual care services in NHS Wales 2010. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

———. 2015. Health and care standards. London: Crown.

World Health Organisation (= WHO). 2002. WHOQOL-SRPB field test instrument. Geneva: WHO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Commentary

Commentary

Spiritual care does not exist in vacuum. The framework conditions of historical circumstances and developments in the history of religion and spirituality as well as political-cultural framework factors are decisive in determining how religious and spiritual facets are interpreted and what significance is attached to these issues in their respective institutional framework – issues that exceed the bio-psycho-social triangle in healthcare.

1 The Importance of Cultural Background and Political Setting

The contribution by Linda Ross and Wilfred McSherry shows that in the United Kingdom the integration of the spiritual dimension in a hospital setting is tough. And this despite the fact that the spiritual dimension was recognized in the British health system (NHS) as early as 1947. As an example, McSherry and Ross make this difficult situation clear by the fact that humanist groups compare spiritual care and infrastructural conditions in financial terms and aim them at one another. Humanists present spiritual care providers and hospital infrastructure as competing for financial resources. As if both were a straight contrast, a zero-sum game. Thus, on the one hand, there are strong tendencies towards the privatization of the religious-spiritual factor and the religious-spiritual care provision; on the other hand, even in the United Kingdom there are regionally different approaches. In Wales, for example, there is clearly a greater sensibility for the spiritual dimension of the patient in the context of ‘care planning in mental health’. This chapter also draws attention to such differences.

A crucial area in the field of spiritual care is that of training. This is exactly where appropriate competences are acquired and sensitivities are instilled. McSherry and Ross bring this out skillfully in identifying gaps in the training of nursing staff. They find out that many nurses have not been prepared for ‘spiritual care’ or feel incompetent to cope with specific demands. Both of them, McSherry and Ross, are therefore careful to include spirituality more centrally in the training processes. They themselves have launched EPICC (‘Enhancing Nurses’ and Midwives’ Competence in Providing Spiritual Care Through Innovative Education and Compassionate Care’), a European-wide project in this context. This research project aims to analyze the shortcomings identified and take steps to remedy them.

2 The Decisive Intersection of Spiritual Care and Nursing

The first point of contact for spiritual concerns and needs in the hospital context is often not the pastor, chaplain or spiritual care provider, but the nursing staff. Spiritual care is also their responsibility. Ross and McSherry focus their attention on this, as both also have a background in nursing. This aspect makes their contribution to the present volume unique and lends it a special authority. Ross and McSherry have also developed important tools for this first contact in the hospital, such as the 2Q-SAM tool. From the spiritual point of view, it is now crucial to work closely with the nursing staff and to find a suitable and understandable common language. It is highly incumbent upon those working in the field of spiritual care to establish and develop a clear and translatable terminology. The factor of education and training comes into play again. In general, Ross and McSherry are particularly sensitive to linguistic terms and terminology. This sensibility for language is particularly relevant in the medical context if one is committed to providing the best care for patients.

3 An Aside Concerning Islamic Spiritual Care in the United Kingdom

One aspect that was not directly addressed in the chapter is the growing area of Islamic pastoral care in hospitals. In the United Kingdom, as in the Netherlands, this is becoming ever more important. The number of Muslim citizens in these countries is steadily increasing. The importance of the issue of Muslim spiritual care was recently pointed out by Dilek Uçak in her contribution to a book on spiritual care in a global context (Simon Peng-Keller/David Neuhold, Spiritual Care im globalisierten Gesundheitswesen, Stuttgart 2019, p. 207–230). Uçak compares spiritual care in European countries like the United Kingdom with that in Turkey and Iran. While in Turkey the religious-political dimension is becoming more important, in Iran spiritual care by the nursing staff is further developed. The Turkish and Iranian contexts could provide Ross and McSherry with new starting points for comparison. In connection with the documentation of clinical pastoral care, it should be mentioned that spiritual care work is also documented in Turkey. The spiritual care giver is required to fill in three text fields, providing a general description of each case, along with measures and results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ross, L., McSherry, W. (2020). Spiritual Care Charting/Documenting/Recording/Assessment: A Perspective from the United Kingdom. In: Peng-Keller, S., Neuhold, D. (eds) Charting Spiritual Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47070-8_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47070-8_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-47069-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-47070-8

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)