Abstract

Donation crowdfunding is a form of internet-enabled fundraising where backers provide funding based on philanthropic motivations without expectation of monetary or material rewards. Despite accounting for only a marginal share of global crowdfunding volumes, donation crowdfunding is a unique model for supporting a wide range of prosocial and charitable causes, while allowing fundraisers to leverage benefits afforded by ICT solutions for more effective and efficient fundraising. The chapter provides an overview of the limited research on donation crowdfunding while highlighting donor motivations and behaviour, as well as drivers of success in donation campaigns. We find that current research suggests that donation behaviour is driven by impure altruism closely linked to intrinsic motivations such as satisfaction, joy, and a sense of belonging. Furthermore, several success drivers of donation crowdfunding campaigns have been identified with respect to factors at the fundraiser, campaign, and platform levels.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Donation crowdfunding

- Philanthropy

- Altruism

- Warm glow

- Non-profit

- Non-investment crowdfunding

- Donor

- Charity

- Prosocial

Introduction

Crowdfunding, as an innovativefundraising channel, aims to exploit the power of the crowd for supporting various kinds of projects which may not easily get funded through traditional ways of fundraising (Lambert and Schwienbacher 2010). In the realm of donation funding, crowdfunding has simplified the process of fundraising for prosocial purposes by integrating information collection, donation transaction, and interactive communication into one standardized process (Belleflamme et al. 2013). This has led some to claim that donation-based crowdfunding has redefined the way of charitable giving is done, as it fuses traditional charitable giving and IT-enabled crowdfunding together (Gleasure and Feller 2016).

Compared with traditional charitable fundraising strategies, donation-based crowdfunding provides a way for potential donors to reach people/groups in need of help without the constraints of physical distance (Tanaka and Voida 2016). Furthermore, from a fundraiser perspective, donation crowdfunding allows for greater efficiencies in terms of geographical reach (Agrawal et al. 2015), reduced transaction and coordination costs (Choy and Schlagwein 2016), as well as richer and more frequent interactions with prospective donors. Accordingly, donation crowdfunding has been employed in a variety of contexts beyond pure charity causes (Gleasure and Feller 2016), and have been applied to support independent journalism (Jian and Shin 2015), indie documentary film productions (Sørensen 2012), cultural heritage projects (Oomen and Aroyo 2011), supporting educational work (Meer 2014), and scientific research (Wheat et al. 2013).

When compared to other crowdfunding models, donations represent one of the smallest models by volume in most regions. In 2017, donation crowdfunding volumes were estimated at, USD 290 million in the Americas (Ziegler et al. 2018a), USD 113 million in Europe including (EUR 53 million in mainland Europe and GBP 41 million in the UK) (Zhang et al. 2018; Ziegler et al. 2019), USD 63 million in the Middle East and Africa (Ziegler et al. 2018c), and USD 53 million in the Asia-Pacific region (Ziegler et al. 2018b). Except for the Middle East and Africa, where donations account for 17% of total the crowdfunding volume, in all other regions this model only represents 1% or less. Accordingly, the share of donation crowdfunding in the total global crowdfunding volume represents only 0.1%.

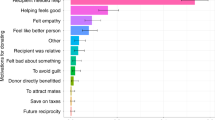

These more modest volumes may be associated with the fact that, unlike other crowdfunding models, donation-based crowdfunding does not include offering the backers material or monetary rewards for their contributions, hence implying different motivations driving related behaviour, as well as relations between fundraisers and backers. More specifically, supporters of donation-based crowdfunding campaigns are said to be motivated by altruism, peer recognition, respect, or esteem rather than by tangible and monetary rewards (Benkler 2011). Hence, to better understand donor behaviour in this context, as well as to boost success of donation campaigns, it is important to understand the working mechanisms of donation-based crowdfunding.

The purpose of this chapter is thus to review current knowledge about donation-based crowdfunding, while examining its core features, and factors driving donor behaviour in this context. Accordingly, we first discuss the current state and characteristics of donation-based crowdfunding, while highlighting its unique aspects. Next, the success factors of donation-based crowdfunding campaigns are summarized based on a review of earlier studies examining them. This is followed by a literature review and discussion concerning the factors impacting donor behaviour. Finally, we conclude by suggesting implications for practice and research.

Characteristics of Donation Crowdfunding

Donation-based crowdfunding has become a new channel to provide monetary support for non-profit, prosocial, and other “do good” initiatives. It is a type of philanthropy (Gerber and Hui 2013) reflecting an emerging and innovative online charity paradigm (Gerber et al. 2012). Similar to other crowdfunding models, the donation-based crowdfunding model is composed of three elements: the campaign initiators/fundraisers, the donors/backers, and the online platforms.

The donation-based crowdfunding platforms offer opportunities for fundraisers to launch campaigns as an open call over the internet for donations to charitable purposes within fixed time durations (Shneor and Munim 2019; Mollick 2014; Belleflamme et al. 2014; Gerber et al. 2012). Compared to the traditional charitable giving, with the help of information technology, donation-based crowdfunding is said to reduce the coordination and transaction costs associated with donation collections in a significant way (Choy and Schlagwein 2016). Besides, donation-based crowdfunding tends to collect small amounts from large crowds instead of seeking large amounts from a small group of affluent donors (Lu et al. 2014). With the involvement of the social network sites (SNS), donation-based crowdfunding initiators can easily broadcast their campaigns to a wider range of potential donors and establish social relationships with such crowds (Liang and Turban 2011).

While traditional charitable giving and donation crowdfunding share many commonalities, they may also differ to varying degrees with respect to several aspects. Here, internet-based crowdfunding platforms and social network sites (SNS), allow for greater real-time interaction (e.g. updates, comments, live streams, etc.) between donors and project initiators throughout the fundraising process (Kuppuswamy and Bayus 2017), as well as afterwards. Incorporating dedicated promotional efforts via SNS, help spread information to the public in new and effective ways (Lambert and Schwienbacher 2010), as in targeted advertising, which increase the probability of successful fundraising.

Other benefits reflect greater process efficiency. First, donation crowdfunding provides opportunities for wider geographical reach, where contributions may be collected from non-local donors with no previous connections to the fundraisers (Agrawal et al. 2015) in a manner that would have been a lot more expensive to achieve otherwise. Second, coordination and transaction costs associated with fundraising may be significantly reduced by the applications of advanced ICT tools (e.g. timely online interactions, digital and mobile payment systems, etc.) (Choy and Schlagwein 2016). And, third, donation crowdfunding also present opportunities to tap into more active donors who may be actively seeking opportunities to contribute to causes on crowdfunding platforms instead of passively waiting for opportunities (Gleasure and Feller 2016), as well as enabling a lower threshold for their involvement and activism, requiring supporters to simply share the campaign with their own networks often through a single-button click.

Success Factors of Donation Crowdfunding Campaigns

Since donation-based crowdfunding is a special type of charitable giving (Gerber and Hui 2013), some factors identified as influencing successful fundraising in traditional charitable giving may also be relevant in donation-based crowdfunding. Research on donor’s willingness to donate in the context of traditional charitable giving is usually associated with altruistic orientation and tendencies (Choy and Schlagwein 2015). Donors are encouraged to donate by their sense of empathy towards specific charitable purposes (Gerber et al. 2012), while representing the emotional state of the individuals (Hoffman et al. 1999).

A recent literature review by Shneor and Vik (2020) has identified seven persistent variables which were found to impact successful donation crowdfunding across multiple studies. First, the target sum set for fundraising is positively associated with success, suggesting that the higher the target the greater the likelihood of success in donation crowdfunding. Second, inclusion of a video in the campaign materials is associated with greater success in comparison to donation campaigns that do not include a video. This finding was linked to lowering the cognitive efforts required for processing campaign information, which is effective at facilitating donations Third, donors react more positively to campaigns closer to them geographically or ideologically. Fourth, female campaign creators are associated with higher success than male campaign creators, which may be related to both more modest funding requirements and better social mobilization capacities of women as driven by empathy and relational focus. Fifth, availability of fundraisers’ socialcapital as reflected by social network size, is also positively associated with success. Sixth, campaigns aiming at educational projects are more likely to receive donations for other purposes. And, finally, the level of maturity of the platform on which campaigns are published is also positively associated with success, suggesting that campaigning on more mature platforms is likely to enhance chances of funding success.

Nevertheless, these still represent slim pickings, as research of success drivers in donation crowdfunding remains limited and mostly explorative (Mollick 2014; Shneor and Vik 2020). Parallel to studies examining the impact of factors related to either the campaign, fundraiser, or platform, an additional line of inquiry into donor behaviour has gradually emerged. We review studies examining donor behaviour in the following sections.

Donor Behaviour in Donation Crowdfunding

Why individuals should contribute to donation-based crowdfunding campaigns has been identified as an interesting and important research question (Gerber and Hui 2013). It is interesting because contribution in the donation-based crowdfunding context may differ from that in other crowdfunding models. This is primarily because, while other crowdfunding models, offer individuals material or monetary rewards for their contribution (Zvilichovsky et al. 2015; Gerber and Hui 2013), donation crowdfunding does not offer such rewards (Gleasure and Feller 2016). Accordingly, the research into donor behaviour in the context of donation crowdfunding has referred to impure altruistic behaviour involving intangible rewards, which may satisfy both certain extrinsic and intrinsic motivations.

Altruism and Charitable Giving

Altruism is often used to explain individuals’ charitable behaviour, and describes a situation where individuals try to help others, even if it comes at some personal cost (Khalil 2004). It is the motivation to increase another person’s welfare, which is contrasted with egoism, the motivation to increase one’s own welfare (Batson and Powell 2003). According, to Khalil (2004), altruism can be explained through two different dimensions: the interactional and the self-actional dimensions. On the one hand, the interactional dimension of altruism suggests that individuals’ altruistic behaviour can be rationally explained. Such approach argues that altruistic behaviour tends to be triggered by delayed external rewards such as reciprocity (Cox 2004), vicarious enjoyment (Kahneman and Miller 1986), and natural-selection-based consequence (Haidt 2007). On the other hand, the self-actional dimension of altruism is normatively anchored. Hence, the self-actional dimension is not based on delayed external rewards but on the attributes of altruistic behaviour such as norms, mind structures, and culture (Khalil 2004).

When examining research conserving altruism in the context of donation crowdfunding, most references seem to rely on the self-actional dimension of altruistic behaviour. According to Andreoni (1990), the self-actional dimension of altruism includes pure altruism, warm glow, and impure altruism. Here, pure altruism describes the situation when individuals donate because it can improve the difficult situation of the recipients. External rewards such as hedonic benefits and warm-glow effects may not explain pure altruism donors’ behaviour (Loewenstein and Small 2007; Andreoni 1990). Pure altruism donors are outcome-based and are primarily concerned with the extent to which a cause deserves support (Carpenter et al. 2008).

The warm-glow effect (Andreoni 1990) refers to the situation where individuals experience pleasure and satisfaction from helping others. Such senses of mental pleasure and satisfaction help to boost individuals’ self-esteem (Fehr and Gächter 2000) and it also explains why individuals with the warm-glow mindset continue to conduct altruistic actions when they can otherwise “free-ride” and wait for others to help (Andreoni 1990). Warm glow is empathy-based. Donors are psychosocially connected with the receivers through the donor–receiver interaction (Park 2000), which is a process in which empathy tends to amplify the positive feelings from helping others or feelings of guilt when refusing to help (Andreoni et al. 2017). In such case, donors may feel compassion (Hoffman et al. 1999) towards certain causes, which may be described in donation crowdfunding campaigns while stimulating donation behaviour that enhance their sense of satisfaction and joy about supporting these causes (Gerber and Hui 2013; Gerber et al. 2012).

Though, the outcome-based pure altruism and empathy-dependent warm glow have provided valuable insights for understanding personal charitable behaviour, some argue that altruistic giving is always triggered by the impure altruism (Andreoni 1990). Impure altruism implies a situation where a combination of both pure altruism and warm glow will influence individuals’ behaviour (Crumpler and Grossman 2008). And when examining the limited literature on donor motivation and behaviour specifically in the donation-based crowdfunding context, it appears that authors often explain donor behaviour by impure altruism (Gerber and Hui 2013; Burtch et al. 2013; Choy and Schlagwein 2015).

Motivation in Charitable Giving

Motivation directs and stimulates human behaviour (Murray 1964). It is viewed as the engine for satisfying physiological needs (Vallerand 1997) while capturing the degree to which a person is moved to perform a particular action (Deci et al. 1991). According to theory, motivations may be classified as either intrinsic or extrinsic (Deci et al. 1991), as well as either individually driven or socially driven (Alam and Campbell 2012; Kaufmann et al. 2011).

One of the prominent motivation theories is the “self-determination theory” (SDT), which explores the individual’s self-motivated or self-determined behaviour (Ryan and Deci 2000). As such, it offers a detailed framework to differentiate between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, while acknowledging that their mutually reinforcing nature also affects individuals’ behavioural intentions (ibid.). Intrinsic motivation is derived from individual’s inherent enjoyment of doing something, and extrinsic motivation stems from the separable outcome of doing something (ibid.). Thanks to its wide appeal and acceptance, this classification has also been employed in earlier crowdfunding literature (e.g. Gerber and Hui 2013; Wang et al. 2019; Zhang and Chen 2019).

Some studies have suggested that charitable giving can be caused by extrinsic motivations such as the satisfaction of personal heroism (Piliavin and Charng 1990) and personal atonement of sins (Schwartz 1973). However, evidence with respect to donation-based crowdfunding, mainly suggests that intrinsic motivations dominate such behaviour (Zhao and Sun 2020; Gleasure and Feller 2016; Bretschneider et al. 2014; Gerber and Hui 2013).

Specifically, individuals were found to contribute to donation-based crowdfunding in order to help others, support causes, or be part of a community (Gerber and Hui 2013). These may be triggered by a sense of empathy, sympathy, nostalgia, reciprocity, or commemoration (Andreoni 1990; Eisenberg and Miller 1987; Sargeant 1999), which may enhance positive feelings with contribution behaviour. Such positive feelings may represent intangible rewards in the form of a sense of enjoyment, competence, and autonomy (Deci and Ryan 1985; Oliver 1980). Such intrinsic motivations may explain donor behaviour, which does not involve material compensation. Furthermore, an earlier study by Zhao and Sun (2020) has shown that providing extrinsic rewards in prosocial campaigns will diminish donors’ intrinsic motivations to donate in the donation-based crowdfunding context.

An alternative approach to the differentiation between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, as suggested by the SDT (Ryan and Deci 2000), emphasizes that motivation is more than a personal concept and has social attributes (Akerlof 2006). Accordingly, classifying motivations as either individually driven or socially driven may also provide valuable insights to investigations of contribution behaviour in the crowd economy in general (Alam and Campbell 2012; Kaufmann et al. 2011), and donation crowdfunding in particular.

Individual motivation is generated by the desire of individuals regardless of the existence of a social group (Cohen et al. 2005). In contrast, social motivation stems from the presence of a social group and individual actions are triggered by the social group (Akerlof 2006). Furthermore, when combining the intrinsic vs. extrinsic dimensions (Deci et al. 1991) with the individual vs. social dimensions of motivation, four sub-categories emerge: individual-extrinsic motivation, individual-intrinsic motivation, social-extrinsic motivation, and social-intrinsic motivation (Choy and Schlagwein 2015). At the individual level, the extrinsic motivation refers to the desire to achieve a specific result by doing something and the intrinsic motivation relates to the individual’s personal satisfaction of doing something. At the social level, an individuals’ social-extrinsic motivation related to signalling compliance with group expectations in terms of action beyond words, and social-intrinsic motivation relates to achieving a sense of belonging to a collective of like-minded people.

In terms of donation-based crowdfunding, donors’ motivations such as helping others and supporting causes are typically individual (Gerber and Hui 2013). For example, individuals may donate to donation-based campaigns because they feel passionate about the campaigns (Choy and Schlagwein 2015). In addition, some donors are socially motived (Akerlof 2006). They donate to achieve social belonging and peer recognition (Alam and Campbell 2012; Bretschneider et al. 2014; Kaufmann et al. 2011). Here, donors donate because they want to be parts of the charitycrowdfunding community and they enjoy engaging and collaborating with the community (Gerber et al. 2012).

Conclusion

Despite representing a small share of global crowdfunding volumes, donation crowdfunding is a unique model for supporting a wide range of prosocial and charitable causes, while allowing fundraisers to leverage benefits afforded by ICT solutions for more effective and efficient fundraising efforts than traditional methods and channels. This chapter has taken stock of the knowledge emerging from the limited research available in the donation crowdfunding context. We have highlighted the motivations of contributors to donate funding to such campaigns as driven by impure altruism, while acknowledging that most work has stressed intrinsic motivations both at the individual and at the social level. Furthermore, the success drivers of donation crowdfunding campaigns have been presented with respect to factors at the fundraiser, campaign, and platform levels. Nevertheless, donation crowdfunding remains an understudied context with much room for further exploration. Some ideas in this direction are presented below.

Implications for Research

While preliminary insights on factors impacting donation crowdfunding success factors are available, they tend to follow recipes adopted from studies conducted in commercial and investment-oriented models. Hence, it is recommended that future studies should devote more attention to examining factors unique to the donation context. Here, research should embark on capturing what successfully triggers aspects associated with donor behaviour, and how do campaign features support the necessary emotive reactions of joy, satisfaction, warm glow, as well as a sense of group belonging and compliance with social expectations. Such approach would require a departure from reliance on platform data, and a shift towards primary data collection through surveying and/interviewing of users. This would help bridge the gap between campaign success and donor behaviour and provide valuable insights how the two hang-together in a theoretically sound manner.

An additional venue for future research may include comparative studies of donation crowdfunding versus traditional donation fundraising practices, crowdfunding dynamics across models, as well as across social, cultural, and sectoral groups. First, studies that will compare crowdfunding versus traditional donation collection channels, may provide evidence and insights about the added value or costs associated with the practice of each, and will be go beyond the speculative suggestions that have been outlined in research thus far. Second, a comparative study across crowdfunding models, can better clarify what are the common drivers and aspects of crowdfunding in general, while highlighting the unique aspects associated with donation crowdfunding beyond the clear differentiation between tangible and intangible rewards and benefits. Finally, studies comparing donation crowdfunding across differing contexts, may help identify sectors, social and cultural groups that may be more receptive to donation crowdfunding than others, as well as different strategies employed in different contexts to encourage donor engagements and contributions.

Implications for Practice

Insights from our review of the current state of donation crowdfunding research and practice may inform platforms in designing their products and services, as well as inform fundraisers interested in running a donation crowdfunding campaign. In this context, platforms should develop features that may enhance donors’ sense of satisfaction and joy from giving. Such features may include interactive visualizations of impact such as progression bars, number of people affected, improved conditions (e.g. gas emission reductions, quantity of water cleansed, etc.), number of equipment units provided to needy, and so on. In addition, platforms may invest in community management features that will allow members to join certain interest groups, while receiving symbolic acknowledgement for their contributions to these groups (e.g. virtual badges, status levels, and public endorsements).

From the fundraiser perspective, fundraisers need to invest in creating a sense of ideological proximity with their prospective donors, employing emotional cues to trigger empathy in their messaging, as well as proactively engage with targeted groups via social media. In addition, since donors do not receive material rewards for their contributions, fundraisers should ensure smooth and ongoing communication with donors about project progress, execution, and impact during and after the campaign. This is both to enable a sense of satisfaction about donation at different points in time and to strategically establish long-term relations with fans, who are prospective future donors as well.

References

Agrawal, A., Catalini, C., & Goldfarb, A. (2015). Crowdfunding: Geography, Social Networks, and the Timing of Investment Decisions. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 24(2), 253–274.

Akerlof, R. J. (2006). A Theory of Social Motivation. Unpublished manuscript, Cambridge, MA.

Alam, S. L., & Campbell, J. (2012). Crowdsourcing Motivations in a Not-for-Profit GLAM Context: The Australian Newspapers Digitisation Program. Australasian Conference on Information Systems.

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477.

Andreoni, J., Rao, J. M., & Trachtman, H. (2017). Avoiding the Ask: A Field Experiment on Altruism, Empathy, and Charitable Giving. Journal of Political Economy, 125(3), 625–653.

Batson, C. D., & Powell, A. A. (2003). Altruism and Prosocial Behavior. In I. B. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of Psychology (pp. 463–484). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2013). Individual Crowdfunding Practices. Venture Capital, 15(4), 313–333.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: Tapping the Right Crowd. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 585–609.

Benkler, Y. (2011). The Unselfish Gene. Harvard Business Review, 89(7–8), 76–85.

Bretschneider, U., Knaub, K., & Wieck, E. (2014). Motivations for Crowdfunding: What Drives the Crowd to Invest in Start-ups? European Conference on Information Systems, Tel Aviv, Association for Information Systems.

Burtch, G., Ghose, A., & Wattal, S. (2013). An Empirical Examination of the Antecedents and Consequences of Contribution Patterns in Crowd-Funded Markets. Information Systems Research, 24(3), 499–519.

Carpenter, J., Connolly, C., & Myers, C. K. (2008). Altruistic Behavior in a Representative Dictator Experiment. Experimental Economics, 11(3), 282–298.

Choy, K., & Schlagwein, D. (2015, May). IT Affordances and Donor Motivations in Charitable Crowdfunding: The “Earthship Kapita” Case. ECIS.

Choy, K., & Schlagwein, D. (2016). Crowdsourcing for a Better World: On the Relation Between IT Affordances and Donor Motivations in Charitable Crowdfunding. Information Technology & People, 29(1), 221–247.

Cohen, A. B., Hall, D. E., Koenig, H. G., & Meador, K. G. (2005). Social Versus Individual Motivation: Implications for Normative Definitions of Religious Orientation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(1), 48–61.

Cox, J. C. (2004). How to Identify Trust and Reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 46(2), 260–281.

Crumpler, H., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). An Experimental Test of Warm Glow Giving. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5–6), 1011–1021.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The General Causality Orientations Scale: Self-Determination in Personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134.

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and Education: The Self-Determination Perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 325–346.

Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). The Relation of Empathy to Prosocial and Related Behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments. American Economic Review, 90(4), 980–994.

Gerber, E. M., & Hui, J. (2013). Crowdfunding: Motivations and Deterrents for Participation. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 20(6), 34.

Gerber, E. M., Hui, J. S., & Kuo, P. Y. (2012, February). Crowdfunding: Why People Are Motivated to Post and Fund Projects on Crowdfunding Platforms. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Design, Influence, and Social Technologies: Techniques, Impacts and Ethics (Vol. 2, No. 11, p. 10). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

Gleasure, R., & Feller, J. (2016). Does Heart or Head Rule Donor Behaviors in Charitable Crowdfunding Markets? International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 20(4), 499–524.

Haidt, J. (2007). The New Synthesis in Moral Psychology. Science, 316(5827), 998–1002.

Hoffman, D. L., Novak, T. P., & Peralta, M. (1999). Building Consumer Trust Online. Communications of the ACM, 42(4), 80–85.

Jian, L., & Shin, J. (2015). Motivations Behind Donors’ Contributions to Crowdfunded Journalism. Mass Communication and Society, 18(2), 165–185.

Kahneman, D., & Miller, D. T. (1986). Norm theory: Comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychological review, 93(2), 136.

Kaufmann, N., Schulze, T., & Veit, D. (2011, August). More than Fun and Money. Worker Motivation in Crowdsourcing-A Study on Mechanical Turk. AMCIS, 11(2011), 1–11.

Khalil, E. L. (2004). What Is Altruism? Journal of Economic Psychology, 25(1), 97–123.

Kuppuswamy, V., & Bayus, B. L. (2017). Crowdfunding Creative Ideas: The Dynamics of Project Backers in Kickstarter. A Shorter Version of This Paper Is In “The Economics of Crowdfunding: Startups, Portals, and Investor Behavior”, L. Hornuf & D. Cumming (eds.).

Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2010). An Empirical Analysis of Crowdfunding. Social Science Research Network, 1578175, 1–23.

Liang, T. P., & Turban, E. (2011). Introduction to the Special Issue Social Commerce: A Research Framework for Social Commerce. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(2), 5–14.

Loewenstein, G., & Small, D. A. (2007). The Scarecrow and the Tin Man: The Vicissitudes of Human Sympathy and Caring. Review of General Psychology, 11(2), 112–126.

Lu, C. T., Xie, S., Kong, X., & Yu, P. S. (2014, February). Inferring the Impacts of Social Media on Crowdfunding. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (pp. 573–582). ACM.

Meer, J. (2014). Effects of the Price of Charitable Giving: Evidence from an Online Crowdfunding Platform. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 103, 113–124.

Mollick, E. (2014). The Dynamics of Crowdfunding: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1–16.

Murray, E. J. (1964). Motivation and Emotion. Prentice-Hall.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469.

Oomen, J., & Aroyo, L. (2011, June). Crowdsourcing in the Cultural Heritage Domain: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communities and Technologies (pp. 138–149). ACM.

Park, E. S. (2000). Warm-Glow Versus Cold-Prickle: A Further Experimental Study of Framing Effects on Free-Riding. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 43(4), 405–421.

Piliavin, J. A., & Charng, H. W. (1990). Altruism: A Review of Recent Theory and Research. Annual Review of Sociology, 16(1), 27–65.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Sargeant, A. (1999). Charitable Giving: Towards a Model of Donor Behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 215–238.

Schwartz, S. H. (1973). Normative Explanations of Helping Behavior: A Critique, Proposal, and Empirical Test. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(4), 349–364.

Shneor, R., & Munim, Z. H. (2019). Reward Crowdfunding Contribution as Planned Behaviour: An Extended Framework. Journal of Business Research, 103, 56–70.

Shneor, R., & Vik, A. A. (2020). Crowdfunding Success: A Systematic Literature Review 2010–2017. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(2), 149–182.

Sørensen, I. E. (2012). Crowdsourcing and Outsourcing: The Impact of Online Funding and Distribution on the Documentary Film Industry in the UK. Media, Culture & Society, 34(6), 726–743.

Tanaka, K. G., & Voida, A. (2016, May). Legitimacy Work: Invisible Work in Philanthropic Crowdfunding. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 4550–4561). ACM.

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 271–360). Academic Press.

Wang, T., et al. (2019). Exploring Individuals’ Behavioral Intentions Toward Donation Crowdfunding: Evidence from China. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 119(7), 1515–1534.

Wheat, R. E., Wang, Y., Byrnes, J. E., & Ranganathan, J. (2013). Raising Money for Scientific Research Through Crowdfunding. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28(2), 71–72.

Zhang, H., & Chen, W. (2019). Backer Motivation in Crowdfunding New Product Ideas: Is It about You or Is It about Me? Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(2), 241–262.

Zhang, B., Ziegler, T., Mammadova, L., et al. (2018). The 5th UK Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

Zhao, L., & Sun, Z. (2020). Pure Donation or Hybrid Donation Crowdfunding. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(2).

Ziegler, T., Johanson, D., King, M., et al. (2018a). Reaching New Heights: The 3rd Americas Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Johanson, D., Zhang, B., et al. (2018b). The 3rd Asia Pacific Region Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Suresh, K., Garvey, K., et al. (2018c). The 2nd Annual Middle East & Africa Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Shneor, R., Wenzlaff, K., et al. (2019). Shifting Paradigms – The 4th European Alternative Finance Benchmarking Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

Zvilichovsky, D., Inbar, Y., & Barzilay, O. (2015). Playing Both Sides of the Market: Success and Reciprocity on Crowdfunding Platforms. Available at SSRN 2304101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zhao, L., Shneor, R. (2020). Donation Crowdfunding: Principles and Donor Behaviour. In: Shneor, R., Zhao, L., Flåten, BT. (eds) Advances in Crowdfunding. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46309-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46309-0_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-46308-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-46309-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)