Abstract

The chapter provides a topical summary of the present research knowledge of equity crowdfunding. It describes the typical equity crowdfunding process, investor characteristics, and investor motivations. Recognizing the limited due diligence efforts of the crowd despite the presence of high information asymmetries, the chapter presents the role of platforms in evaluating and preselecting target ventures. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of rapidly observable campaign features and signals of venture quality in investor decision making, while also emphasizing the relevance of experienced investors and the herding tendency of crowdinvestors. The chapter offers a comparison of equity crowdfunding investors with traditional providers of early-stage equity financing including micro funders, angel investors, and venture capital funds. It concludes with a discussion of the challenges and potential of equity crowdfunding.

Parts of the content of this chapter have been extracted from the overview chapter of the Aalto University Doctoral Dissertation referred to as — Lukkarinen (2019) and are provided here with the author’s permission.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Equity crowdfunding

- Investment

- Entrepreneurial finance

- Venture capital

- Angel investors

- Micro funders

- Due diligence

- Early stage funding

- Information asymmetry

- Investor decision

Introduction

Since the first online equity crowdfundingplatform was established in France in 2008, equity crowdfunding has rapidly gained foothold across the world as an equity financing mechanism for early-stage entrepreneurial ventures. It allows ventures to gather funds for growth and expansion, and some ventures have indeed reached strong growth after their equity crowdfunding campaign, although many others have failed (Schwienbacher 2019). The investor base is composed of unaccredited as well as accredited investors, and increasingly also professional investors such as angel investors and venture capital funds (Wang et al. 2019).

The equity crowdfunding market grew strongly in the early 2010s across the world. From 2016 onwards, volumes in some regions have experienced declines driven by regulatory uncertainty and constraints (Garvey et al. 2017; Ziegler et al. 2018a). The largest individual countries for equity crowdfunding are the United Kingdom (EUR 378 million in 2017) and the United States (EUR 209 million in 2017) (Ziegler et al. 2018a, 2019). Figure 5.1 presents yearly equity crowdfunding volumes by region.

Equity Crowdfunding Principles

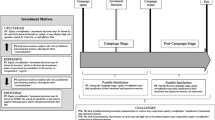

While various different practices and conventions exist in equity crowdfunding across platforms and countries, certain principles have become widely established. Figure 5.2 presents a typical equity crowdfunding process.

Typical equity crowdfunding process under the all-or-nothing model. (Source: Modified from Lukkarinen et al. 2016)

The first contact between ventures and platforms is commonly inbound: interested ventures contact the platform. However, contact may also be established through outbound origination whereby the platform approaches attractive ventures, or through third-party referrals. Platforms vet and filter the ventures interested in conducting a campaign, with the extent of legal and financial due diligence varying by platform (Löher 2017; Schwienbacher 2019). If the outcome of the assessment is favourable, the venture proceeds to prepare and implement the crowdfunding campaign. The preselection funnel of platforms is often highly selective. In Europe, 6% of applicant ventures were deemed qualified by platforms and were thus onboarded to conduct a campaign in 2017 (Ziegler et al. 2019). Most equity crowdfunding platforms operate under the all-or-nothing model, in which the campaign must reach its pre-set minimum funding target in order to become successful and for the venture to receive the invested funds. If the minimum target is not reached, the funds are returned to investors (Tuomi and Harrison 2017).

The revenue model of platforms typically relies mostly on success fees or listing fees from fundraisers (Barbi and Mattioli 2019; Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2016; Shafi 2019). Compared with traditional forms of early-stage equity investing, the standardized online nature of the equity crowdfunding investment process allows for very low transaction costs. Indeed, low investor-side transaction costs, along with low minimum investment thresholds, are key factors enabling the participation of large crowds in equity crowdfunding (Kim and Viswanathan 2019). Accordingly, the bargaining power of individual crowd investors both pre- and post-investment is usually low. As fundraisers and platforms define the campaign details beforehand, prospective investors cannot influence transaction terms or covenants (Hornuf and Schmitt 2017). General shareholder rights vary by country and by platform. While some platforms call for the use of the same share class for equity crowdfunding investors as for other equity investors (Vismara 2018), others offer shareholders’ agreements in which the shares offered via crowdfunding form a separate class with no voting rights (Frydrych et al. 2014; Hornuf and Neuenkirch 2017; Tuomi and Harrison 2017; Walthoff-Borm et al. 2018).

Investor Characteristics and Motivations

Investor Characteristics

Equity crowdfunding investors are a very diverse group of individuals with varying levels of professional and educational backgrounds (Lukkarinen et al. 2017) and investor professionalism (Guenther et al. 2018). Thus far, the majority of equity crowdfunding investments have been made by individuals who have no professional affiliation with investing. However, platforms are also attracting angel investors and venture capitalists who are seeking portfolio diversification and the convenience of standardized online investment processes (Bessière et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019). For instance, in the Australia-based sample of Guenther et al. (2018), 10% of equity crowdfunding investors were accredited or professional investors.

Equity crowdfunding investors are predominantly male, although the share of female investors has been growing (Ziegler et al. 2018a, d, 2019). Investor age varies but averages at around 40, and investors’ experience with other forms of investing ranges from none to extensive (Baeck et al. 2014; Guenther et al. 2014; Hornuf and Neuenkirch 2017; Lukkarinen et al. 2017; Mohammadi and Shafi 2018).

Heterogeneous Motivations

Investors’ motivations for investing in equity crowdfunding are very heterogeneous, and they vary both between investors and between campaigns (Goethner et al. 2018; Lukkarinen et al. 2017). Accordingly, research has suggested that investments would be motivated mainly by an aim to earn financial returns (Baeck et al. 2014; Cholakova and Clarysse 2015; Kim and Viswanathan 2019), mainly by intrinsic reasons such as obtaining personal satisfaction (Schwienbacher and Larralde 2012), or by a combination of both (Collins and Pierrakis 2012; Daskalakis and Yue 2017). Survey results by Bretschneider and Leimeister (2017) indicate that equity crowdfunding investors are motivated by several factors, such as the ability to receive recognition, to influence campaign outcomes, to create an online image, and to receive returns or rewards, but not by altruistic motives. Vismara (2019), on the other hand, suggests that some equity crowdfunding investors may invest out of a wish to support sustainable development in the world. As such, no consensus exists as of yet about investor motivations in equity crowdfunding, perhaps due to their inherent heterogeneity and the rapid evolution of the industry.

Investors’ Relationship with Fundraisers

While part of the investments in equity crowdfunding come from the family, friends, and other social connections of the entrepreneurs, the majority of investment activity is driven by the “true crowd” (Ahlers et al. 2015; Vismara 2018). According to a survey conducted by Guenther et al. (2014), 4% of equity crowdfunding investors are family members or friends of the fund seekers. Similarly, a survey by Lukkarinen et al. (2017) indicates that personal knowledge of the entrepreneur or the team was on average not considered an important decision criterion by equity crowdfunding investors. Furthermore, a dataset sourced from the database of an Australian equity crowdfunding platform indicates that 3% of equity crowdfunding investors are somehow connected to the venture (Guenther et al. 2018).

Thus, while some equity crowdfunding investments originate through the connections and marketing activities of fundraising ventures, platforms have a central role in attracting prospective investors to the campaign websites (Baeck et al. 2014). Consequently, rather than relying solely on their existing networks, entrepreneurs who conduct equity crowdfunding campaigns make an effort to build new ties and to expand their networks by attracting new investors via the platform (Brown et al. 2019).

Investing Behaviour

Investors’ Limited Due Diligence

Although the equity crowdfunding market has been growing in size and relevance, with possibly significant implications for fundraising ventures (White and Dumay 2017), equity crowdfunding has limited centrality from the point of view of individual investors. It is usually a sporadic activity, with most investors having invested in only one or few equity crowdfunding campaigns on any focal platform (Baeck et al. 2014; Bapna 2019; Mohammadi and Shafi 2018), and with the median or average sums invested running relatively low, typically in the low thousands of euros (Bapna 2019; Block et al. 2018; Mahmood et al. 2019). Indeed, most investors describe the sums they invest via equity crowdfunding as “small” and as representing a small part of their overall investment portfolios (Estrin et al. 2018).

Accordingly, and in line with bounded rationality theory (Simon 1991), the investment target evaluation process of equity crowdfunding investors tends to be very limited. A survey of equity crowdfunding investors by Guenther et al. (2014) found that, on average, investors spend less than an hour to study the business plan, less than an hour on the campaign page, and less than an hour to study the venture’s home page. Equity crowdfunding platforms, on the other hand, usually dedicate significant time and effort to evaluate each venture before deciding on its suitability for fundraising, thereby providing investors with a certain level of quality assurance for the campaigns that become available on platforms (Cumming et al. 2018; Guenther et al. 2018; Lukkarinen et al. 2016).

Investing time and effort in one-on-one communications between small-sum investors and fundraisers makes little economic sense in equity crowdfunding (Moritz et al. 2015). Accordingly, the majority of equity crowdfunding investors do not communicate directly with the entrepreneur (Guenther et al. 2014; Moritz et al. 2015). However, entrepreneurs and investors utilize digital pseudo-personal communications, such as videos, online investor relations channels, and social media, which enable investors to form a view of the venture and its management (Moritz et al. 2015).

Information asymmetries in the equity crowdfunding setting are high, as prospective investors possess considerably less knowledge about the fundraising venture than do the entrepreneurs (Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2018). While investors do not usually conduct lengthy target evaluation processes or engage in personal communications to mitigate the hindering effect of information asymmetries, they do tend to take into account rapidly observable campaign features (Lukkarinen et al. 2016). These include the presence (Li et al. 2016) and length (Vismara et al. 2017) of videos, the minimum allowed investment (Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2018a; Lukkarinen et al. 2016), and visual cues such as logos (Mahmood et al. 2019). Investment decision criteria that equity crowdfunding investors have highlighted as important in investor surveys include the perceived informativeness of the campaign page and materials, clarity and uniqueness of the business idea and products, characteristics of the entrepreneur and the team, the explanation for the planned used of funds, perceived openness and trustworthiness, and the presence of a credible lead investor (Bapna 2019; Kang et al. 2016; Lukkarinen et al. 2017; Moritz et al. 2015; Ordanini et al. 2011).

Ventures can signal the attractiveness of the investment opportunity and the underlying venture quality to prospective investors in a variety of ways (Ahlers et al. 2015). The share of equity retained by the entrepreneurs in the equity offering signals the entrepreneurs’ belief in the future prospects of the venture and influences investor interest (Ahlers et al. 2015; Vismara 2016). Entrepreneurs’ human capital, as measured by business education and entrepreneurial experience, serves as a low-ambiguity signal of venture quality and thereby drives investments (Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2018). A venture’s intellectual capital can signal innovation capabilities, managerial skills, and overall venture quality (Ralcheva and Roosenboom 2016) while also creating entry barriers to competitors (Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2018), although findings about the effect of the possession of intellectual property rights on campaign success remain mixed (Ahlers et al. 2015; Kleinert et al. 2020). As business failure can signal a lack of entrepreneurial skill, prospective equity crowdfunding investors discount entrepreneurs who have previously experienced a business failure, unless the investors receive evidence that the failure was due to bad luck rather than a lack of entrepreneurial skill (Zunino et al. 2017). Furthermore, investors prefer taking the high risks inherent in equity crowdfunding (Kleinert et al. 2020) when the entrepreneurs seek to reduce uncertainty by offering detailed financial information (Ahlers et al. 2015).

Updates posted by entrepreneurs on the campaign site during the campaign have a positive impact on fundraising performance, as they can convey messages about venture value to prospective investors in a trustworthy and easily observable manner (Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2018b; Li et al. 2016). Update content matters, with updates about developments that have taken place during the campaign considered most relevant by investors (Block et al. 2018).

Angel and venture capital investors typically conduct extensive, or at least moderate, due diligence on their investment targets (Fried and Hisrich 1994; Van Osnabrugge 2000). Ventures that have already secured Angel or venture capital investors are thus more likely to successfully raise funding in equity crowdfunding campaigns, as the presence of professional investors helps mitigate the adverse effect of information asymmetries (Kleinert et al. 2020; Mamonov and Malaga 2018).

Importance of Other Investors’ Actions

Most equity crowdfunding platforms allow for digital visibility, with all prospective investors usually able to see in real-time the total amount already invested, the number of investors or investments already committed to a campaign, and investment-related comments written by other users (Ahlers et al. 2015; Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2018b; Kim and Viswanathan 2019; Lukkarinen et al. 2016). This contrasts the funding dynamics of initial public offerings, in which investors do not know the amount of money already invested by others at the time of subscription (Vismara 2016). Accordingly, when making investment decisions, equity crowdfunding investors consider not only the available venture information and predetermined campaign characteristics, but also the within-campaign funding dynamics, thereby at least partially relying on the behaviour of others.

In particular, later investors have the opportunity to take the behaviour of previous investors into account in their decision making (Vismara 2018). Campaigns with a larger number of early investors are more likely to become successful, possibly because early investments send a signal of trust and confidence to prospective later investors and because early investors may contribute to the word-of-mouth around a campaign (Lukkarinen et al. 2016; Vulkan et al. 2016). Experienced early investors, in particular, have a strong influence on the investment decisions of prospective later investors (Kim and Viswanathan 2019; Vismara 2018), and especially on the decisions of small crowdinvestors (Cumming et al. 2019).

Furthermore, the size of previous investments positively predicts subsequent investment activity at campaign level, as large investments may send a signal of the respective investor possessing knowledge that others do not have (Åstebro et al. 2018; Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2018b; Vulkan et al. 2016). Similarly, the amount of time that has passed since the most recent investment in a campaign has a negative effect on the likelihood and size of subsequent investments, as an absence of investments can be indicative of a lack of investors who would possess positive private signals of the campaign (Åstebro et al. 2018). Such herding behaviour can increase the likelihood of investors investing in low-quality ventures in which they might not invest without the cues observed from the crowd. Consequently, Stevenson et al. (2019) introduce the term crowd bias to refer to “an individual’s tendency to follow the opinions of the crowd despite the presence of contrary objective quality indicators” (p. 348).

Most platforms host discussion boards on which users can pose questions to the entrepreneurs and discuss the investment opportunity with other users. Discussions tend to have a positive effect on investment activity, although the effect depends on the discussion topic (Kleinert and Volkmann 2019). Positive comments by previous investors, in particular, have a positive effect, as they may contain positive information about the attractiveness of the venture (Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2018b).

Local Bias

Much like investors in other forms of investing (e.g., Grinblatt and Keloharju 2001), equity crowdfunding investors are locally biased. Suggested reasons for equity crowdfunding investors’ tendency to invest in ventures located geographically close to them include access to better and more tangible information and an ability to better monitor the venture (Guenther et al. 2018; Hornuf and Schmitt 2017). The local bias effect is weaker for financially more literate investors, perhaps because they are more likely to pursue risk reduction through portfolio diversification (Hornuf and Schmitt 2017).

A distinct aspect of local bias is investors’ tendency to invest domestically. This preference stems from the benefits of geographic proximity, difficulties caused by differences in legal frameworks, and the burden and risks associated with foreign currency investments (Niemand et al. 2018). Interestingly, while investors are indeed sensitive to geographic distance when investing domestically, distance is not relevant in cross-border investments, perhaps because of the difficulty of leveraging local knowledge in any cross-border investment, regardless of distance (Guenther et al. 2018; Maula and Lukkarinen 2019).

The share of cross-border investments has been growing, however, along with platforms’ increasing internationalization efforts. While the United States is still strongly domestically focused (Ziegler et al. 2018a), cross-border investments represented 9% of funding outflows and 16% of funding inflows among European platforms (Ziegler et al. 2019) and 31% and 22% of outflows and inflows, respectively, among Asia Pacific platforms (Ziegler et al. 2018d) in 2017.Footnote 1 The Australia-based sample of Guenther et al. (2018) portrayed a 9% share of cross-border investors, whereas the Finland-based sample of Maula and Lukkarinen (2019) and the Germany-based sample of Hornuf and Schmitt (2017) featured 8% and 9% cross-border investments, respectively. As cross-border investing opens up a large multiple of investment opportunities compared to domestic investing, the attention that cross-border investors pay to foreign campaigns becomes an important driver of investors’ investment choices (Maula and Lukkarinen 2019).

Comparison of Early-Stage Equity Financing Forms

Equity crowdfunding addresses partly the same market as traditional forms of entrepreneurial finance, most notably angel investors, venture capitalists, and micro funders.Footnote 2 Partly, however, it serves to fund such ventures that might otherwise be left unfunded (Harrison and Mason 2019). Table 5.1 presents a comparative summary of different forms of early-stage equity financing. Salient similarities between neighbouring forms are highlighted in italic.

In several respects, equity crowdfunding investors bear resemblance to traditional micro funders. Both make relatively small high-risk investments using their own money, with the investing activity not being their main occupation. While some of their investments are motivated by returns, both can also invest out of a willingness to support the target venture. They both expend very limited effort to evaluate the target, although the decision making of equity crowdfunding investors may also partly rely on their knowledge of the platform having already pre-evaluated the target (Tuomi and Harrison 2017).

A key differentiator between equity crowdfunding and more traditional forms of early-stage equity financing is the digital nature of online crowdfunding, which renders it possible for ventures to gather investments from large numbers of people without personal entrepreneur-investor interactions and with a high degree of visibility towards investors (Horvát et al. 2018; Kim and Viswanathan 2019).

It is worth noting in this context that, from the viewpoint of an entrepreneurial venture, the different forms of financing need not be mutually exclusive, nor is their sequential order invariable. Entrepreneurial ventures can use different sources of funding at different lifecycle stages. Ventures that have successfully secured financing through equity crowdfunding have been shown to be more likely to attract investments from angel investors or venture capitalists in follow-up funding rounds (Hornuf et al. 2018), whereas ventures with unsuccessful equity crowdfunding campaigns may fail with no opportunities for follow-up funding (Walthoff-Borm et al. 2018). In addition, ventures can use several forms simultaneously. Complementarities, such as a possibility of co-investing in deals, have been previously identified between venture capital funds and angel investors (Harrison and Mason 2000). Similarly, equity crowdfunding campaigns have begun attracting investments from angel investors and venture capital funds, with angel investors making use of the digital screening and investing opportunities offered by equity crowdfunding platforms, and with venture capitalists acting as lead investors in high-volume deals (Brown et al. 2019; Itenbert and Smith 2017).

Discussion

Since its inception in 2008, online equity crowdfunding has experienced strong market growth. Consequently, equity crowdfunding has gathered wide research interest, and it has come to justify its existence as a standalone research target.

The investor base in equity crowdfunding is diverse, with some investors originating from the close social networks of the entrepreneurs, but with much activity also being driven by the “true crowd”. In addition, angel and venture capital investors are increasingly making use of the opportunities offered by equity crowdfunding platforms. While investors’ motivations for investing are heterogeneous, a wish for financial returns is important. In accordance with the limited centrality of equity crowdfunding from the investor’s point of view, crowdinvestors spend very limited time evaluating target ventures. They focus on rapidly observable campaign features, signals of venture quality, and the actions of other investors when making investment decisions. Equity crowdfunding complements the spectrum of traditional venture financing mechanisms. While it bears certain resemblance to other forms of early-stage equity financing, equity crowdfunding is clearly distinguishable by its special features stemming from its digital nature, in particular its high degree of investor-side visibility into campaign funding dynamics and the low contributions of time and money required for making an investment.

Implications for Research

Research on equity crowdfunding can anchor itself in the wider context of not only crowdsourcing or crowdfunding, but also that of early-stage equity investing or even public stock investing (Cummings et al. 2019). As findings can differ by investor type and by venture type, research on equity crowdfunding can benefit from taking into account the heterogeneity of investors’ motivations, decision criteria, and characteristics, on the one hand, and the diversity of fundraisers, on the other hand. Furthermore, as investors and platforms are increasingly active across country borders, cross-country and cross-platform research identifying similarities and differences across country and platform contexts is increasingly needed. Finally, although research about campaign success factors and investor features in equity crowdfunding is already abundant (Mochkabadi and Volkmann 2020), it dates empirically back to the early stages of industry development. As industry characteristics and dynamics vary across lifecycle stages, further research on equity crowdfunding at platform, investor, and investment level becomes necessary as the industry matures. Furthermore, the maturing state of the industry makes it increasingly possible to assess post-campaign outcomes for investors and for fundraisers.

Implications for Practice

The present research findings on equity crowdfunding investors have also practical implications. An awareness of investors’ limited due diligence and investors’ reliance on non-traditional decision criteria when making equity crowdfunding investments can support policymakers in their pursuit of the optimal level of regulation. The heterogeneity of the funder space offers platforms opportunities to differentiate their services at platform level and at investor level. Platforms can accommodate the existence of different investor segments by focusing explicitly on certain segments and selecting fundraisers in accordance with segment preferences, or by targeting and serving different segments in different ways. As certain demographic segments, notably women, remain a minority, platforms and fundraisers may consider adopting approaches to increasingly attract such presently underserved segments. Platforms’ increased targeting efforts can improve their ability to match investors and ventures and thus enhance ventures’ ability to gather funding.

Conclusion

The key challenges presently faced by the equity crowdfunding industry relate to investor returns, share liquidity, and platform profitability (Schwienbacher 2019). Although the long-term term outcome of the industry is yet to be seen, equity crowdfunding carries potential to offer a positive impact on new venture financing and development (Brown et al. 2019; Mochkabadi and Volkmann 2020) and even on the wider society and environment (Testa et al. 2019; Vismara 2019). To entrepreneurial ventures, equity crowdfunding offers an alternative form of equity financing that they may turn to out of choice or out of necessity (Walthoff-Borm et al. 2018). To investors, it offers an opportunity to diversify their investment portfolios across company lifecycle stages, financial instruments, and, increasingly, across geographies.

Notes

- 1.

Funding inflows represent investments made into fundraisers located in the platform country by investors located outside that country. Funding outflows represent investments made into fundraisers located outside the platform country by investors located in the platform country (definitions as used in the survey by Ziegler et al. 2019).

- 2.

Micro funders, or micro angels, can be defined as informal early-stage investors who contribute limited amounts of their personal financial and human capital resources to purchase equity in entrepreneurial ventures that are majority owned by others. They can include family, friends, as well as more distant “foolhardy” investors (Avdeitchikova 2008; De Clercq et al. 2012; Maula et al. 2005; Szerb et al. 2007). The concept dates back to the time before online crowdfunding.

References

Ahlers, G. K., Cumming, D., Günther, C., & Schweizer, D. (2015). Signaling in Equity Crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 955–980.

Åstebro, T., Fernández, M., Lovo, S., & Vulkan, N. (2018). Herding in Equity Crowdfunding. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3084140.

Avdeitchikova, S. (2008). On the Structure of the Informal Venture Capital Market in Sweden: Developing Investment Roles. Venture Capital, 10(1), 55–85.

Baeck, P., Collins, L., & Zhang, Z. (2014). Understanding Alternative Finance: The UK Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge.

Bapna, S. (2019). Complementarity of Signals in Early-stage Equity Investment Decisions: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment. Management Science, 65(2), 933–952.

Barbi, M., & Mattioli, S. (2019). Human Capital, Investor Trust, and Equity Crowdfunding. Research in International Business and Finance, 49, 1–12.

Bessière, V., Stéphany, E., & Wirtz, P. (2019). Crowdfunding, Business Angels, and Venture Capital: An Exploratory Study of the Concept of the Funding Trajectory. Venture Capital, forthcoming.

Block, J., Hornuf, L., & Moritz, A. (2018). Which Updates During an Equity Crowdfunding Campaign Increase Crowd Participation? Small Business Economics, 50(1), 3–27.

Bretschneider, U., & Leimeister, J. M. (2017). Not Just an Ego-trip: Exploring Backers’ Motivation for Funding in Incentive-based Crowdfunding. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 26(4), 246–260.

Brown, R., Mawson, S., & Rowe, A. (2019). Start-ups, Entrepreneurial Networks and Equity Crowdfunding: A Processual Perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 80, 115–125.

Cholakova, M., & Clarysse, B. (2015). Does the Possibility to Make Equity Investments in Crowdfunding Projects Crowd Out Rewards-based Investments? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 145–172.

Collins, L., & Pierrakis, Y. (2012). The Venture Crowd: Crowdfunding Equity Investment into Business. London, UK: Nesta. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from http://www.nesta.org.uk/publications/venture-crowd.

Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2017). De-segmenting Research in Entrepreneurial Finance. Venture Capital, 19(1–2), 17–27.

Cumming, D., Hervé, F., Manthé, E., & Schwienbacher, A. (2018). Hypothetical Bias in Equity Crowdfunding. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3114526.

Cumming, D., Meoli, M., & Vismara, S. (2019). Investors’ Choices Between Cash and Voting Rights: Evidence from Dual-class Equity Crowdfunding. Research Policy, 48(8), 103740.

Cummings, M. E., Rawhouser, H., Vismara, S., & Hamilton, E. L. (2019). An Equity Crowdfunding Research Agenda: Evidence from Stakeholder Participation in the Rulemaking Process. Small Business Economics, forthcoming.

Daskalakis, N., & Yue, W. (2017). User’s Perceptions of Motivations and Risks in Crowdfunding with Financial Returns. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2968912.

De Clercq, D., Meuleman, M., & Wright, M. (2012). A Cross-country Investigation of Micro-angel Investment Activity: The Roles of New Business Opportunities and Institutions. International Business Review, 21(2), 117–129.

EBAN. (2014). Investment Principles and Guidelines. European Business Angel Network. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from http://www.eban.org/knowledge-center/.

Estapé-Dubreuil, G., Ashta, A., & Hédou, J.-P. (2016). Micro-equity for Sustainable Development: Selection, Monitoring and Exit Strategies of Micro-angels. Ecological Economics, 130, 117–129.

Estrin, S., Daniel Gozman, D., & Khavul, S. (2018). The Evolution and Adoption of Equity Crowdfunding: Entrepreneur and Investor Entry into a New Market. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 425–439.

Fried, V. H., & Hisrich, R. D. (1994). Toward a Model of Venture Capital Investment Decision Making. Financial Management, 23(3), 28–37.

Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., Kinder, T., & Koeck, B. (2014). Exploring Entrepreneurial Legitimacy in Reward-based Crowdfunding. Venture Capital, 16(3), 247–269.

Garvey, K., Chen, H.-Y., Zhang, B., Buckingham, E., Ralston, D., Katiforis, Y., et al. (2017). Cultivating Growth: The 2nd Asia Pacific Region Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Goethner, M., Luettig, S., & Regner, T. (2018). Crowdinvesting in Entrepreneurial Projects: Disentangling Patterns of Investor Behavior. Jena Economic Research Papers 2018-018. Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena.

Grinblatt, M., & Keloharju, M. (2001). How Distance, Language, and Culture Influence Stockholdings and Trades. Journal of Finance, 56(3), 1053–1073.

Guenther, C., Hienerth, C., & Riar, F. (2014). The Due Diligence of Crowdinvestors: Thorough Evaluation or Gut Feeling Only? Paper Presented at the 12th International Open and User Innovation Conference, Boston, Massachusetts, July 28–30.

Guenther, C., Johan, S., & Schweizer, D. (2018). Is the Crowd Sensitive to Distance? How Investment Decisions Differ by Investor Type. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 289–305.

Harrison, R. T., & Mason, C. M. (2000). Venture Capital Market Complementarities: The Links Between Business Angels and Venture Capital Funds in the United Kingdom. Venture Capital, 2(3), 223–242.

Harrison, R. T., & Mason, C. M. (2019). Venture Capital 20 Years On: Reflections on the Evolution of a Field. Venture Capital, 21(1), 1–34.

Hornuf, L., & Neuenkirch, M. (2017). Pricing Shares in Equity Crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, 48(4), 795–811.

Hornuf, L., & Schmitt, M. (2017). Does a Local Bias Exist in Equity Crowdfunding? Max Planck Institute for Innovation & Competition Research Paper No. 16-07. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2801170.

Hornuf, L., & Schwienbacher, A. (2016). Crowdinvesting: Angel Investing for the Masses? In H. Landström & C. Mason (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Business Angels (pp. 381–397). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hornuf, L., & Schwienbacher, A. (2018a). Internet-based Entrepreneurial Finance: Lessons from Germany. California Management Review, 60(2), 150–175.

Hornuf, L., & Schwienbacher, A. (2018b). Market Mechanisms and Funding Dynamics in Equity Crowdfunding. Journal of Corporate Finance, 50, 556–574.

Hornuf, L., Schmitt, M., & Stenzhorn, E. (2018). Equity Crowdfunding in Germany and the UK: Follow-up Funding and Firm Failure. Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition Research Paper No. 17–09.

Horvát, E.-Á., Wachs, J., Wang, R., & Hannák, A. (2018). The Role of Novelty in Securing Investors for Equity Crowdfunding Campaigns. Paper Presented at the 6th AAAI Conference on Human Computation and Crowdsourcing HCOMP 2018, Zurich, Switzerland, July 5–8.

Itenbert, O., & Smith, E. E. (2017). Syndicated Equity Crowdfunding: The Trade-off Between Deal Access and Conflicts of Interest. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2933822.

Kang, M., Gao, Y., Wang, T., & Zheng, H. (2016). Understanding the Determinants of Funders’ Investment Intentions on Crowdfunding Platforms. Industrial Management Data Systems, 116(8), 1800–1819.

Kim, K., & Viswanathan, S. (2019). The Experts in the Crowd: The Role of Experienced Investors in a Crowdfunding Market. MIS Quarterly, 43(2), 347–372.

Kleinert, S., & Volkmann, C. (2019). Equity Crowdfunding and the Role of Investor Discussion Boards. Venture Capital, 21(4), 327–352.

Kleinert, S., Volkmann, C., & Grünhagen, M. (2020). Third-party Signals in Equity Crowdfunding: The Role of Prior Financing. Small Business Economics, 54(1), 341–365.

Landström, H. (1993). Informal Risk Capital in Sweden and Some International Comparisons. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(6), 525–540.

Li, X., Tang, Y., Yang, N., Ren, R., Zheng, H., & Zhou, H. (2016). The Value of Information Disclosure and Lead Investor in Equity-based Crowdfunding: An Exploratory Empirical Study. Nankai Business Review International, 7(3), 301–321.

Löher, J. (2017). The Interaction of Equity Crowdfunding Platforms and Ventures: An Analysis of the Preselection Process. Venture Capital, 19(1–2), 51–74.

Lukkarinen, A. (2019). Drivers of Investment Activity in Equity Crowdfunding. Doctoral dissertation, Aalto University School of Business. 190 pages. Aalto University publication series DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS, 40/2019. ISBN 978-952-60-8444-2 (electronic). 978-952-60-8443-5 (printed) http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-60-8444-2.

Lukkarinen, A., Teich, J. E., Wallenius, H., & Wallenius, J. (2016). Success Drivers of Online Equity Crowdfunding Campaigns. Decision Support Systems, 87, 26–38.

Lukkarinen, A., Seppälä, T., & Wallenius, J. (2017). Investor Motivations and Decision Criteria in Equity Crowdfunding. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3263434.

MacMillan, I. C., Siegel, R., & Narasimha, P. N. S. (1985). Criteria Used by Venture Capitalists to Evaluate New Venture Proposals. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 119–128.

Mahmood, A., Luffarelli, J., & Mukesh, M. (2019). What’s in a Logo? The Impact of Complex Visual Cues in Equity Crowdfunding. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(1), 41–62.

Mamonov, S., & Malaga, R. (2018). Success Factors in Title III Equity Crowdfunding in the United States. Electronic Commerce and Research Applications, 27, 65–73.

Mason, C. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2008). Measuring Business Angel Investment Activity in the United Kingdom: A Review of Potential Data Sources. Venture Capital, 10(4), 309–330.

Maula, M., & Lukkarinen, A. (2019). Attention Across Borders: Investor Attention as a Driver of Investment Choices in Cross-Border Equity Crowdfunding. Retrieved November 21, 2019, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3487467.

Maula, M., Autio, E., & Arenius, P. (2005). What Drives Micro-angel Investments? Small Business Economics, 25(5), 459–475.

Mochkabadi, K., & Volkmann, C. K. (2020). Equity Crowdfunding: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Small Business Economics, 54(1), 75–118.

Mohammadi, A., & Shafi, K. (2018). Gender Differences in the Contribution Patterns of Equity-crowdfunding Investors. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 275–287.

Moritz, A., Block, J., & Lutz, E. (2015). Investor Communication in Equity-based Crowdfunding: A Qualitative-empirical Study. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 7(3), 309–342.

Niemand, T., Angerer, M., Thies, F., Kraus, S., & Hebenstreit, R. (2018). Equity Crowdfunding Across Borders: A Conjoint Experiment. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 24(4), 911–932.

Ordanini, A., Miceli, L., Pizzetti, M., & Parasuraman, A. (2011). Crowd-funding: Transforming Customers into Investors Through Innovative Service Platforms. Journal of Service Management, 22(4), 443–470.

Piva, E., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2018). Human Capital Signals and Entrepreneurs’ Success in Equity Crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, 51(3), 667–686.

Politis, D., & Landström, H. (2002). Informal Investors as Entrepreneurs: The Development of an Entrepreneurial Career. Venture Capital, 4(2), 78–101.

Prowse, S. (1998). Angel Investors and the Market for Angel Investments. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22(6-8), 785–792.

Ralcheva, A., & Roosenboom, P. (2016). On the Road to Success in Equity Crowdfunding. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2727742.

Rossi, M. (2014). The New Ways to Raise Capital: An Exploratory Study of Crowdfunding. International Journal of Financial Research, 5(2), 8–18.

Sahlman, W. A. (1990). The Structure and Governance of Venture-capital Organizations. Journal of Financial Economics, 27(2), 473–521.

Schwienbacher, A. (2019). Equity Crowdfunding: Anything to Celebrate? Venture Capital, 21(1), 65–74.

Schwienbacher, A., & Larralde, B. (2012). Crowdfunding of Entrepreneurial Ventures. In D. Cumming (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance (pp. 369–391). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Shafi, K. (2019). Investors’ Evaluation Criteria in Equity Crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, forthcoming.

Signori, A., & Vismara, S. (2018). Does Success Bring Success? The Post-offering Lives of Equity-Crowdfunded Firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 50, 575–591.

Simon, H. A. (1991). Bounded Rationality and Organizational Learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 125–134.

Stevenson, R. M., Ciuchta, M. P., Letwin, C., Dinger, J. M., & Vancouver, J. B. (2019). Out of Control or Right on the Money? Funder Self-efficacy and Crowd Bias in Equity Crowdfunding. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(2), 348–367.

Streletzki, J.-G., & Schulte, R. (2013). Which Venture Capital Selection Criteria Distinguish High-flyer Investments? Venture Capital, 15(1), 29–52.

Sudek, R. (2006). Angel Investment Criteria. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 17(2), 89–103.

Sullivan, M. K., & Miller, A. (1996). Segmenting the Informal Venture Capital Market: Economic, Hedonistic, and Altruistic Investors. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 25–35.

Szerb, L., Rappai, G., Makra, Z., & Terjesen, S. (2007). Informal Investment in Transition Economies: Individual Characteristics and Clusters. Small Business Economics, 28(2), 257–271.

Testa, S., Roed Nielsen, K., Bogers, M., & Cincotti, S. (2019). The Role of Crowdfunding in Moving Towards a Sustainable Society. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 66–73.

Tuomi, K., & Harrison, R. T. (2017). A Comparison of Equity Crowdfunding in Four Countries: Implications for Business Angels. Strategic Change, 26(6), 609–615.

Tyebjee, T. T., & Bruno, A. V. (1984). A Model of Venture Capitalist Investment Activity. Management Science, 30(9), 1051–1066.

Van Osnabrugge, M. (2000). A Comparison of Business Angel and Venture Capitalist Investment Procedures: An Agency Theory-based Analysis. Venture Capital, 2(2), 91–109.

Vismara, S. (2016). Equity Retention and Social Network Theory in Equity Crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, 46(4), 579–590.

Vismara, S. (2018). Information Cascades Among Investors in Equity Crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(3), 467–497.

Vismara, S. (2019). Sustainability in Equity Crowdfunding. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 98–106.

Vismara, S., Benaroio, D., & Carne, F. (2017). Gender in Entrepreneurial Finance: Matching Investors and Entrepreneurs in Equity Crowdfunding. In A. N. Link (Ed.), Gender and Entrepreneurial Activity (pp. 271–288). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Vulkan, N., Åstebro, T., & Sierra, M. F. (2016). Equity Crowdfunding: A New Phenomena. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 5, 37–49.

Walthoff-Borm, X., Schwienbacher, A., & Vanacker, T. (2018). Equity Crowdfunding: First Resort or Last Resort? Journal of Business Venturing, 33(4), 513–533.

Wang, W., Mahmood, A., Sismeiro, C., & Vulkan, N. (2019). The Evolution of Equity Crowdfunding: Insights from Co-investments of Angels and the Crowd. Research Policy, 48(8), 103727.

White, B. A., & Dumay, J. (2017). Business Angels: A Research Review and New Agenda. Venture Capital, 19(3), 183–216.

Wilson, K. E., & Testoni, M. (2014). Improving the Role of Equity Crowdfunding in Europe’s Capital Markets. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2502280.

Wiltbank, R. E. (2009). Siding with the Angels: Business Angel Investing – Promising Outcomes and Effective Strategies. London, UK: Nesta. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from https://www.effectuation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/wiltbank-business-angel-investing-1.pdf.

Zhang, B., Ziegler, T., Mammadova, L., Johanson, D., Gray, M., & Yerolemou, N. (2018). The 5th UK Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Johanson, D., King, M., Zhang, B., Mammadova, L., Ferri, F., et al. (2018a). Reaching New Heights: The 3rd Americas Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Shneor, R., Garvey, K., Wenzlaff, K., Yerolemou, N., Hao, R., et al. (2018b). Expanding Horizons: The 3rd European Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Suresh, K., Garvey, K., Rowan, P., Zhang, B., Obijiaku, A., et al. (2018c). The 2nd Annual Middle East & Africa Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Suresh, K., Johanson, D., Zhang, B., Shenglin, B., Luo, D., et al. (2018d). The 3rd Asia Pacific Region Alternative Finance Industry Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Ziegler, T., Shneor, R., Wenzlaff, K., Odorović, A., Johanson, D., Hao, R., et al. (2019). Shifting Paradigms: The 4th European Alternative Finance Benchmarking Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance.

Zunino, D., van Praag, M., & Dushnitsky, G. (2017). Badge of Honor or Scarlet Letter? Unpacking Investors’ Judgment of Entrepreneurs’ Past Failure. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper; No. 2017-085/VII. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Tinbergen Institute.

Acknowledgement

The author gratefully acknowledges that this work was supported by a grant from the Finnish Foundation for Share Promotion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lukkarinen, A. (2020). Equity Crowdfunding: Principles and Investor Behaviour. In: Shneor, R., Zhao, L., Flåten, BT. (eds) Advances in Crowdfunding. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46309-0_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46309-0_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-46308-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-46309-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)