Abstract

This chapter examines the earnings trajectories of divorced mothers in Germany. It explores earnings changes around the time of divorce, and investigates how the gendered division of work and employment patterns during marriage affects the post-divorce earnings of women with children. The data come from the German Statutory Pension Register, which provides monthly employment and earnings histories as of age 14, as well as complete fertility biographies and marriage histories for the divorced women we study. The analytical sample of this study contains 6850 women with minor children who entered the divorce process between 1992 and 2013. The analysis shows that the mothers’ earnings increased around the time of divorce, and that the mothers of the most recent divorce cohort had higher earnings than the mothers of the earlier divorce cohorts. Despite these increases, the divorced mothers earned only 40% of average earnings. The mothers’ earnings patterns during marriage and the ages of their children explain a large share of these earnings patterns after divorce.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Germany has seen a rapid increase in women’s employment rates in the last decade (Eurostat 2019). Most of this growth can be attributed to an expansion of marginal and part-time employment, and, in recent years, to some increases in full-time employment among women (Geisler et al. 2016). However, the comparatively high female employment rate in Germany hides the fact that the earned income of the average woman is only a fraction of her total household earnings, because she is unlikely to be working full-time (OECD 2017). When a couple separates, the female partner’s precarious income situation often becomes apparent, especially if she is a mother. Thus, in Germany, the risk of poverty for lone mothers is four times higher than it is for partnered mothers (Hübgen 2018). In addition, women’s employment discontinuities and low earnings during marriage can have long-lasting effects on their financial well-being, not only around the time of divorce, but over the long term, as their statutory pension benefits are based on their current earnings (Hammerschmid and Rowold 2019; Madero-Cabib and Fasang 2016).

Previous research on the economic consequences of divorce mainly focused on equivalent household income. These studies found moderate changes in income for men, but sharp declines in income for women around the time of divorce and separation (Andreß et al. 2003; Andreß and Bröckel 2007; Burkhauser et al. 1991; Duncan and Hoffman 1985; Finnie 1993; Hauser et al. 2016; Jarvis and Jenkins 1999; Leopold 2018; Poortman 2000).Footnote 1 A comparison of these consequences across time revealed that the economic situations of divorced women have improved little in recent decades. Bröckel and Andreß (2015), who tracked women’s equivalent income after divorce in Germany from the mid-1980s until the late 2000s reported that there were no substantial changes. This result was unexpected, given that women’s labour force participation has increased significantly over time.

Cross-national studies have suggested that women expand their employment activities after divorce or separation (Van Damme et al. 2009; Van Damme and Kalmijn 2014). Furthermore, there is some evidence that women’s earnings increase after divorce or separation. Several US studies reported earnings increases among divorced women (e.g., Bradbury and Katz 2002; Smock 1994); Tamborini et al. 2015). Moreover, Raz-Yurovich (2013) and Herbst and Kaplan (2016) found for Israel that the earnings of divorced women increased. Nylin (in this volume) showed for Sweden that the earnings development of separated mothers was more negative in the long run than for coupled mothers. This is in line with Raz-Yurovich (2013) who finds a reduction in the salary growth rates of women following divorce. While some research on this topic has been conducted in the German context, these studies did not cover more recent developments. In our study, we seek to close this research gap by drawing on recent data for Germany to investigate how mothers’ earnings change around the time of divorce.

Our analysis uses register data of the German statutory pension insurance, which includes monthly data on women’s earnings over the whole life course, as well as monthly fertility biographies and marital histories of divorcees. The size of the dataset allows us to provide a detailed description of subgroups of women, which has previously not been possible because of the small sample sizes of the national panel surveys that were used to study this issue in the past. Our main interest lies in examining changes in earnings around the time of divorce across time; that is, across the divorce cohorts of 1992–1999, 2000–2007, and 2008–2013. On the basis of these data, we explore the relationship between individual earnings and relevant family-related covariates. The method we employ in our analysis is pooled OLS-regression.

Institutional Context

In comparative studies, Germany serves as the prime example of a country where the male breadwinner model remains dominant (Andreß 2003; Andreß et al. 2006; Lewis 1992; Lewis and Ostner 1994). Thus, family and social policies in Germany have long supported family arrangements in which the male partner is the primary earner. Since the female employment rate in Germany has increased substantially over the last several decades (Eurostat 2019), it has recently been argued that the dominant family arrangement in the country is now the modern male breadwinner model, in which the wife works part-time; and that the dual earner model is gaining strength (Trappe et al. 2015). However, in Germany, relative to other European countries, the share of part-time work among employed women is high, the average hours worked in part-time jobs are low, and the resulting relative contribution of women to household earnings is likewise low (OECD 2017). The employment of mothers in Germany has long been impeded by the insufficient availability of child care, especially for children under age three. In 2017, about 93% of 3–5-year-olds and around 33% of children under age three were in child care. Only 10 years previously, the share of children under age three in child care was just 16% (Federal Statistical Office 2018: 66ff.). The shares of children in day care who are under age three and are in full-time care vary strongly by region. Moreover, the employment behaviour of mothers differs by region, with eastern German women being more likely than western German women to enrol their children in day care, and to be in full-time employment. The expansion of child care in Germany was accompanied by the legal entitlement to access to institutional child care. Parents have been entitled to a child care place after their child turns 3 years old since 1996, and after their child turns 1 year old since 2013.Footnote 2

Overall in Germany, women’s opportunities to combine work and family life have improved significantly. At the same time, however, the individual responsibilities of divorced mothers have increased. This shift is most evident in a change in the maintenance law enacted in 2008. Prior to 2008, a mother who divorced was not expected to work, and was entitled to receive rather generous ex-spousal maintenance until her youngest child reached age eight. After that point, the mother was expected to work part-time. Moreover, if the mother did not work full-time, the support she received from her ex-spouse did not end until the youngest child turned 15 years old. Until that point, the care-giving parent generally received ex-spousal maintenance as well as child alimony from the non-resident parent. The legal context changed abruptly as a result of a decision of the German Federal Constitutional Court that requested to abolish the unequal treatment of children born to unmarried mothers, who previously had shorter maintenance claims than children of married mothers (BVerfG, Beschluss des Ersten Senats vom 28. Februar 2007, 1 BvL 9/04, Rn. (1-78)). The reform meant a drastic cut in ex-spousal maintenance claims to the level of those for unmarried mothers. Since 2008, separated and divorced mothers receive maintenance payments only until their youngest child turns 3 years old. After this point, the mother is expected to take up employment or extend her working hours. Child alimony payments were not affected by this reform. While these entitlements apply equally to lone fathers, the share of single parents in Germany who are mothers was 88% in 2017 (Federal Statistical Office 2018: 55).

The recent changes in the institutional context in Germany that have incentivised single mothers to take more individual responsibility, and to combine work and family life to a greater extent than in the past, would suggest that divorced women in Germany have been expanding their employment activities (and their earnings) over time. In view of our analyses of earnings changes around divorce across time, we expect to find that mothers’ earnings tend to increase during the divorce process, and across time.

Literature Review

Divorce and Household Income

The divorce literature has unanimously found that women who separate or divorce face adverse economic consequences, and that they generally suffer far greater losses than men (Andreß et al. 2003; Andreß and Bröckel 2007; Burkhauser et al. 1991; Duncan and Hoffman 1985; Finnie 1993; Hauser et al. 2016; Jarvis and Jenkins 1999; Leopold 2018; Poortman 2000). According to these studies, women’s economic losses range from 24% to 44% of household income (adjusted for the composition of the household), whereas the changes in men’s income levels range from losses of 7% to gains of 6%. It appears that the adverse effects divorced women face are not primarily attributable to the loss of economies of scale when a two-adult household splits into two single-person households. Instead, the main reason women suffer more than men in divorce is that the economically weaker party loses access to the pooled household income of the couple, which, on average, results in high relative and absolute income losses for the female partner. Average income losses following divorce vary considerably across countries, as they depend on the level of inequality in market income between the partners, and the opportunities of the lower-income partner to remain or become active on the labour market around the time of the divorce. The main explanations for the gender gap in the economic outcomes of the partners following union dissolution are women’s lower labour force attachment levels before separation and divorce, and women’s greater likelihood of being the main carer for the children after union dissolution.

In addition to individual characteristics, the institutional context plays an important role in mitigating adverse effects. Uunk (2004) showed in a comparison of 14 European countries that income-related policy measures mitigate the negative consequences more than employment-related measures. However, institutional conditions play a decisive role not only in alleviating adverse outcomes, but in providing policies that support the autonomy of women, and especially of mothers, by encouraging them to participate in the labour market while married (Andreß et al. 2006).

While the options for combining market work and family obligations have improved somewhat in Germany during the last two to three decades, recent research on the changing economic consequences of divorce for women in Germany has found that divorced women’s income situations have not improved since the 1990s, but have instead either stagnated or even deteriorated (Bröckel and Andreß 2015; Hauser et al. 2016); and that gender differences in divorce outcomes remain substantial (Leopold 2018: Table S1). This pattern stability in divorce outcomes has also been found for Switzerland (Kessler 2018).

Divorce and Women’s Earnings

While the majority of studies on the economic consequences of divorce for women focused on household income, fewer studies have examined the employment rates and individual earnings of divorced women. Cross-national studies that included Germany reported that women’s employment levels increased after divorce or separation (Van Damme et al. 2009; Van Damme and Kalmijn 2014). Women in Germany are among those with the largest increases in employment, primarily because their pre-divorce employment rates tend to be low (Van Damme et al. 2009). In addition, there are a few existing studies on the employment behaviour of single mothers, including mothers who were previously cohabiting as well as mothers who were married. The findings of these studies suggest that institutional factors, such as the availability of child care, affect the employment behaviour of single mothers in Germany more than individual factors, such as low education or early motherhood (Hancioglu and Hartmann 2014). Zagel (2014, 2015) pointed out that the importance of these factors for single mothers in Germany differs depending on whether they are lower or middle class.

Studies that examine the impact of divorce on individual earnings have been rare. Research conducted in the US has found persistent increases in women’s earnings after divorce, especially for women who did not remarry (Tamborini et al. 2015; Couch et al. 2013). Raz-Yurovich (2013) reported that divorced salaried women in Israel had increased employment stability and a higher number of jobs, but that their earnings increases were not significant. But Herbst and Kaplan (2016) found, also for Israel, that salaried mothers’ earnings increased significantly up to 3 years after divorce.

The advantage of using household income to measure the economic outcomes of women is that it provides a more complete picture of the income situation of a household. However, this approach is also based on the assumption that each of the married spouses has equal access to this income. The question of whether married couples actually share the household income equally has been raised (Findlay and Wright 1996). Moreover, an increase in the household income following a divorce might be caused by the presence of a new partner in the household. By using individual earnings, we can better estimate in our study the amount of income the women had at their disposal before and after divorce.

Data and Method

Data & Sample Selection

The dataset we draw upon is a scientific use file of a sample of insurance accounts (VSKT2015) of the German statutory pension insurance (Himmelreicher and Stegmann 2008). It contains monthly data on women’s earnings during their whole life course starting at age 14, as well as monthly fertility biographies of women (Kreyenfeld and Mika 2006). It was combined with information from a register of pension splitting procedures. These data include monthly marital histories for women who divorced. This combined dataset (SUF-VSKT-VA 2015) is newly available as a scientific use file from the Research Data Centre of the German Statutory Pension Fund, and provides the basis for this investigation.Footnote 3 There are many advantages to using this dataset. Unlike the data that have typically been used to address similar research questions, such as data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP), these data do not suffer from attrition or non-response bias. The insured individuals have a vested interest in disclosing their earnings and fertility details, as their pension calculations are based on the correctness and the completeness of their data. Furthermore, the dataset includes a much larger number of divorcees than most social science surveys. This large sample size allows us to perform analyses of subgroups of the divorced population that previous studies were not able to undertake. However, there are also some disadvantages associated with using this dataset. First, the data are not a representative sample of the resident German population. Certain groups, such as civil servants and farmers, are not covered. Furthermore, not all divorces are included in the data, as only divorces that involved a “pension splitting procedure” are registered. Pension splitting means that the pension entitlements that were accrued during the marriage by both partners are added up and then divided equally between the spouses. While this is the default process for dividing retirement benefits in German divorce law, couples can agree to exclude pension splitting from the divorce proceedings. Little is known about the characteristics of the couples who do not use pension splitting, but it is likely that most are couples with short marriages or marriages during which the partners had more or less equal earnings (Keck et al. 2019).

The SUF-VSKT-VA 2015 dataset is comprised of 267,812 individuals born between 1948 and 1985. Younger cohorts are not included because insurance accounts are “cleared” for the first time at age 29, and complete information is available only after this “clearance” has occurred. Furthermore, only individuals with German citizenship who were living in Germany in 2015 are included in this data file. For the purposes of our analyses, we further restrict the sample to women who started the divorce process between 1992 and 2013, and who were between 20 and 54 years old at the time of the divorce. In addition, we have restricted the analysis to individuals in West Germany, as understanding the employment and divorce patterns of East Germans would have required a separate investigation. We have furthermore limited the sample to individuals who divorced after at least 3 years of marriage. Finally, we include first marriages only. After these selection criteria are applied, we end up with a total sample of 6850 divorced mothers.

Variables

Individual Earnings

The dependent variable is individual labour earnings measured in the form of pension points. Pension points are accumulated throughout the life course, not only from employment, but from creditable periods, such as periods spent in child-rearing, education, work disability, or even unemployment. For our analyses, we only use pension points earned from employment that is subject to social security payments to mirror individual labour earnings. This includes earnings from certain forms of self-employment that are subject to social security payments, such as self-employment as a child care professional, a midwife, or a crafts person. An individual earns one pension point based on the yearly average income. The yearly average income is adjusted on an annual basis, and amounted to €35,363 for West Germany in 2015 (Appendix 1, Book VI of the German Social Welfare Code). The maximum number of pension points an individual can earn in 1 year is about two points (€72,600 in 2015, Appendix 2, Book VI of the German Social Welfare Code). Earnings above this threshold are not pensionable earnings, and thus do not increase pension entitlements. This threshold is of little significance for women, as they rarely reach it. We create a measure of yearly earnings by summing up the earnings of 12 months per calendar year. Women who were not employed are included, and thus contribute zero earnings for the months and years they were not employed. We measure earnings in 1-year intervals, starting from 2 years before the divorce until 2 years after the divorce. Thus, we end up with 4-year episodes that include five points in time around the event. We argue that the majority of the employment changes associated with divorce happen during this period.

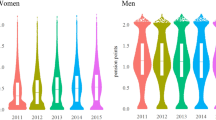

Figure 4.1 shows the distribution of earnings in the year of divorce for mothers of the divorce cohorts 1992–1999, 2000–2007, and 2008–2013.Footnote 4 The share of mothers with zero earnings (and who thus were not employed for the whole year when the divorce was filed) decreased substantially across the cohorts. Accordingly, the share of divorced mothers with positive earnings increased across the cohorts. The increases were largest in the two lower earnings groups (0 ≤ 0.2 earnings points and 0.2 ≤ 0.4 earnings points) and in the highest earnings group (more than 0.8 earnings points). The share of mothers with medium earnings (0.4 ≤ 0.6 and 0.6 ≤ 0.8) remained rather stable across the divorce cohorts. This changed distribution might point to a growing divide in mothers’ earnings at the time of divorce.

Number of children

A person is defined as a mother if she had at least one child under the age of 18 at the time of the divorce. We can assume that the birth of children is recorded very reliably, as each child increases the individual’s qualifying period and total amount of pension points.

Age of youngest child

This variable gives the age of the youngest minor child at the time of the divorce.

Duration of marriage

The marriage duration is the time between the month of the marriage and the month of the postal delivery of the divorce petition from the family court to the defendant (see “divorce” variable below).

Maximum yearly earning points during marriage

This variable reflects the highest yearly amount of earning points the woman ever earned during her marriage. It serves as a proxy for the woman’s earnings potential.

Divorce

The pension data do not include information on the exact timing of the separation. Instead, the end of the so-called “marriage time” is marked by the postal delivery of the divorce petition from the family court to the defendant.Footnote 5 It is this event that is referred to as divorce throughout the chapter. Due to a statutory waiting time of 1 year before a divorce can be filed in Germany, the actual separation of the couple would have taken place at least 10 months before the event that we call divorce here.

Divorce cohort

We distinguished three divorce cohorts: 1992 to 1999, 2000 to 2007, and 2008 to 2013. We use the year 1999 as a cut-point to enable us to compare our results to the findings of Bröckel and Andreß (2015), who looked at the time trends in divorce consequences before and after the turn of the millennium. We also use the year 2007 as another cut-point to account for the 2008 changes in the regulations for spousal maintenance that drastically reduced maintenance claims.

Age at marriage, age at divorce

These variables are self-explanatory. We exclude them from the regression analyses due to multicollinearity, but report their means in the summary statistics in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 shows the summary statistics of the variables that are included in the analyses. We can see that the age at marriage, the age at first birth, and the age at divorce of divorced mothers increased across the divorce cohorts. The number of children remained stable across the cohorts, but the age of the youngest child increased. It is possible that these composition changes led to changes in the labour force attachment of divorced mothers over time, as mothers’ labour force attachment generally increases with the age of the youngest child. The maximum number of yearly earnings points women had during marriage increased only slightly across the divorce cohorts. This finding can be attributed to a decrease in the number of mothers with zero earnings that was accompanied by an increase in earnings, mostly at the lower end of the earnings distribution (see Fig. 4.1).

Research Design

The analysis consists of a descriptive part and a section that contains regression analysis. The descriptive part describes the evolution of women’s earnings around the time of divorce by showing the mean earnings by the time since the divorce. Therefore, we created a balanced panel of five yearly observations per individual. The earliest possible divorce took place in 1992, with a corresponding observation window that lasted from 1990 to 1994; the last possible divorce took place in 2013, with an observation window that lasted from 2011 to 2015.

We first display the descriptive results; that is, mothers’ earnings before and after divorce across the three divorce cohorts. Second, we examine the role of family-related determinants on earnings around the time of divorce in a regression model. This analysis relies on pooled OLS regression (Giesselmann and Windzio 2012). As we use several observations per individual, we employ cluster robust standard errors. Third, to find out whether subgroups of divorced mothers had similar changes in their earnings across time, we show interactions between relevant variables and the three divorce cohorts. A main disadvantage of our investigation is that we only have divorcees in our sample, and therefore cannot consider changes in employment and earnings behaviour in the population of married mothers.

Results

Earnings during the Divorce Process

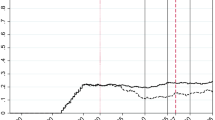

The findings on mothers’ earnings around the time of divorce point to two important developments (Fig. 4.2). First, the earnings of divorced mothers increased constantly throughout the divorce process. Second, the average earnings levels of mothersFootnote 6 around the time of divorce increased slightly across the divorce cohorts, especially in the years after the divorce. Between the earlier cohorts, the change was rather small from the 2 years before to the 2 years after divorce. However, the earnings increase started earlier in the 2000–2007 divorce cohort than in the 1992–1999 divorce cohort, which is, nevertheless, a favourable development. The somewhat more substantial earnings increases took place in the most recent cohort, 2008–2013. Both 2 years before and 2 years after divorce, the average earnings of divorced mothers in this cohort were higher than those in the two preceding cohorts. More generally, the rather low average earnings of the divorcing mothers should be pointed out. Two years before they divorced, and thus while they were still married, their earnings were between 20% and 25% of the average earnings (one earnings point corresponds to the average earnings of a given year). Four years later, after steady increases, their earnings were still less than 40% of the average earnings.Footnote 7

Results from Pooled OLS-Regression

The main focus of the multivariate analyses is on the development of earnings across the divorce cohorts. Table 4.2 shows the results of two pooled OLS-regression models, with Model 1 being the empty model and Model 2 being the model with the full set of control variables.Footnote 8 First, Model 1 confirms the descriptive finding of a positive development in earnings in the most recent divorce cohort. Mothers of the 2008–2013 divorce cohort had significantly higher earnings than mothers of the 1992–1999 divorce cohort. The change in divorced mothers’ earnings between 1992–1999 and 2000–2007 was positive, but was small and insignificant.

After adding control variables, the size of the earnings increases for the 2008–2013 divorce cohort compared to the 1990s cohort is somewhat reduced (Model 2 in Table 4.2). The control variables for the number of children and the age of the youngest child reflect the known relationships. Having more children and younger children tends to inhibit the employment of mothers during marriage and after divorce, and thus decreases the earnings of divorced mothers. Interestingly, having three or more children was not more detrimental to mothers’ earnings than having two children in contrast to having one child. The role of marital earnings for the earnings of divorced mothers was likewise important. We find a significant positive relationship between mothers’ marital earnings and their earnings around the time of divorce.

As a last step, we show the earnings changes across divorce cohorts for groups of mothers by the age of the youngest child (Fig. 4.3) and by marital earnings (Fig. 4.4). Both figures show that the changes in earnings across the divorce cohorts were not the same for all groups of mothers. As Fig. 4.3 shows, only mothers with children under age twelve increased their earnings. The earnings increase was largest for mothers with children aged three to five and aged six to eleven. An increase for these age groups might be a consequence of the maintenance law reform of 2008, which increased the employment obligations for mothers with children of those ages. The earnings of mothers with children aged twelve to 17 even showed a small decrease across the divorce cohorts.Footnote 9 As a side effect, the differences between these subgroups of mothers by the age of the youngest child decreased over time.

Determinants of individual earnings, divorced mothers in West Germany with minor children, Predictive margins from pooled OLS-regression, interaction between divorce cohort and age of the youngest child

Source: SUF-VSKT-VA 2015, own calculations

Note: Additionally controlling for all variables included in Model 2 of Table 4.2

Determinants of individual earnings, divorced mothers in West Germany with minor children, Predictive margins from pooled OLS-regression, interaction between divorce cohort and maximum amount of yearly marital earnings

Source: SUF-VSKT-VA 2015, own calculations

Note: Additionally controlling for all variables included in Model 2 of Table 4.2

Notes: Additionally controlling for all variables included in Model 2 of Table 4.2

Finally, in Fig. 4.4, the development of mothers’ earnings by marital earnings is displayed. First, the figure shows the large earnings disparities between these subgroups, especially between the mothers with the highest marital earnings and all of the other mothers. More importantly, the positive trend of increased earnings around the time of divorce between the latest and the earliest divorce cohort took place only for the two higher income groups with marital earnings above 0.5 earnings points. For the two lower earnings groups, earnings stagnated at a very low level. This finding adds to our general observation that the economic divide within the group of divorced mothers has been growing over time.

Discussion

This study has capitalised on German register data to show that the earnings of divorced mothers increase considerably during the process of divorce. Furthermore, we have found that there were major changes in employment and earnings across the divorce cohorts we studied, with the most recent cohort of divorced women having the highest average earnings. However, while these developments seem positive, the overall picture was bleaker when we compared the earnings of divorced women with average earnings in Germany. The average earnings of divorced West German mothers are found to be far below the levels necessary to be financially independent, both around the time of divorce and thereafter. Another important finding from our study is that social differences among divorced mothers grew over time. On average, the earnings of divorced mothers increased across the observed divorce cohorts. However, this positive trend did not take place for all groups of mothers considered here. The mothers with zero or low marital earnings of the most recent divorce cohort of 2008–2013 fared no better than similar mothers of the 1992–1999 divorce cohort. Moreover, the results of the regression clearly show that mothers’ low average earnings around the time of divorce were the result of both factors that were relevant at the time of divorce, like having young children; and factors that were relevant before the divorce, such as low marital earnings. Together, these factors inhibited mothers’ employment behaviour and reduced their earnings at the time of divorce.

Our investigation contributes to the literature in many ways. First, there is a dearth of research on the question of how divorce impacts individual earnings. In previous studies on the economic consequences of divorce, mothers’ earnings trajectories have usually been hidden behind measures of household income following divorce. While household income is an important measure, it is a poor indicator of the individual economic independence of women. Second, our study went beyond prior research, as the register data we used allowed us to discern differences across population subgroups.

Despite the many benefits of using these register data, it also comes with some serious caveats. The main caveat of the analyses is that we were only able to examine divorced women, because the register data include detailed marital histories only for those who were divorced. Thus, we were unable to identify the married women in the data, who could have served as a suitable control group. It is, for example, possible that the married mothers experienced similar earnings changes over a 5-year period, either because their children grew older and needed less intensive care, or because their income rose due to seniority. Moreover, when thinking about the increases we observed across the cohorts, we should consider the possibility that the improved availability of child care and the increased pressure following the maintenance reform improved the employment and earnings situations of all mothers. It should also be noted that, despite these developments, we found that the average earnings of divorcing mothers were quite low while they were still married. Their average earnings 2 years before divorce did not increase between 1992–1999 and 2000–2007. We therefore assume that part of the positive time trend can be attributed to the improved employment and earnings situations of divorced mothers. To the extent that we have overestimated the positive relationship between divorce and earnings, the adverse financial situation of divorced mothers in West Germany appears even starker.

Despite these caveats, there are major policy conclusions that can be derived from this investigation. Divorce may be seen as a trigger event that serves to reveal the imbalances in wage labour and care responsibilities between mothers and fathers. Such imbalances already exist during the years when women are married and raising children, especially in a (modern) male breadwinner context like Germany. Our findings on the impact of divorce on earnings are not primarily the consequence of divorce itself. Instead, they are mainly the result of an unequal distribution of market work and care work between the partners. Therefore, policy attempts to improve the financial situations of divorced mothers need to start focusing on the time when women are marrying and forming a family.

Notes

- 1.

This list includes only studies in which both women and men were included.

- 2.

Another step towards promoting a dual earner model was taken in 2007, with the enactment of a parental leave reform. Since the reform, paid leave has been limited to a maximum of 12 months, with a replacement rate of 65% for those with middle income levels, and up to 100% for those with low income levels. Unpaid leave can be taken for an additional 2 years. Two months of paid leave for the partner that expire if not used were also added. This led to a significant increase in the share of fathers taking leave, from 3% before the reform in 2006 to 36% in 2015 (BMFSFJ 2018: 16). While this reform was an important turning point in German family policies, it is of no major relevance for this investigation, as only a few of the women in our sample had their first child after the reform.

- 3.

- 4.

As the distribution of earnings does not follow a normal distribution, we also used the natural logarithm of earnings points. To calculate the natural logarithm, we have set values of zero to a small positive amount of 0.0001. Using the log of earnings in the regressions yielded similar results in terms of the signs of the coefficients, the size of the coefficients relative to the reference group, and the significance of the results. However, as the coefficients were more difficult to interpret, we decided to report unlogged earnings.

- 5.

Neither the date of the actual separation of the couple nor the date of the effective divorce are relevant for the calculation of pensions. Therefore, these dates are not included in the data. Only the so-called “marriage time” is relevant for the equalization of pension points, which were jointly accumulated by both spouses during their marriage.

- 6.

As we mentioned earlier, mothers with zero earnings are included.

- 7.

The increase across cohorts from 0.33 (1990–1999) to 0.38 (2007–2013) earnings points 2 years after divorce corresponds to about €1770 of gross yearly income in 2015 euros.

- 8.

We use categorical variables of those explained in section “Variables”.

- 9.

Additional analyses have shown that the finding for mothers of children aged 12–17 was mainly driven by mothers with children aged 16 and 17.

References

Andreß, H.-J. (2003). Die ökonomischen Risiken von Trennung und Scheidung im Ländervergleich: Ein Forschungsprogramm. [The economic risks of separation and divorce in international comparison: A research programme]. Zeitschrift für Sozialreform, 49(4), 620–651.

Andreß, H.-J., Borgloh, B., Güllner, M., Wilking, K. (2003). Wenn aus Liebe rote Zahlen werden. Über die wirtschaftlichen Folgen von Trennung und Scheidung. [When love turns into being in the red. About the economic consequences of separation and divorce]. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Andreß, H.-J., & Bröckel, M. (2007). Income and life satisfaction after marital disruption in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(2), 500–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00379.x.

Andreß, H.-J., Borgloh, B., Bröckel, M., Giesselmann, M., & Hummelsheim, D. (2006). The economic consequences of partnership dissolution: A comparative analysis of panel studies from Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, and Sweden. European Sociological Review, 22(5), 533–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcl012.

BMFSFJ. (2018). Väterreport: Vater sein in Deutschland heute. [Fathers‘ report: Being a father in Germany today]. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend.

Bradbury, K., & Katz, J. (2002). Women’s labor market involvement and family income mobility when marriages end. New England Economic Review, 4, 41–74.

Bröckel, M., & Andreß, H.-J. (2015). The economic consequences of divorce in Germany: What has changed since the turn of the millennium? Comparative Population Studies, 40(3), 277–312. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2015-04en.

Burkhauser, R. V., Duncan, G. J., Hauser, R., & Berntsen, R. (1991). Wife or frau, women do worse: A comparison of men and women in the United States and Germany after marital dissolution. Demography, 28(3), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061461.

BverfG. (2007). Beschluss des Ersten Senats vom 28. Februar 2007 - 1 BvL 9/04 -, Rn. (1-78). http://www.bverfg.de/e/ls20070228_1bvl000904.html.

Couch, K. A., Tamborini, C. R., Reznik, G., & Phillips, J. W. R. (2013). Divorce, women’s earnings, and retirement over the life course. In K. Couch, M. C. Daly, & J. Zissimopoulos (Eds.), Lifecycle events and their consequences: Job loss, family change, and declines in health (pp. 133–157). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Duncan, G. J., & Hoffman, S. D. (1985). A reconsideration of the economic consequences of marital dissolution. Demography, 22(4), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061584.

Eurostat. (2019). Employment and activity by sex and age – annual data [lfsi_emp_a]. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do. Accessed 19 July 2019.

Federal Statistical Office. (2018). Datenreport 2018. Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. [Data report 2018: A social indicators report for the Federal Republic of Germany]. Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) and Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Findlay, J., & Wright, R. E. (1996). Gender, poverty, and the intra-household distribution of resources. Review of Income and Wealth, 42(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.1996.tb00186.x.

Finnie, R. (1993). Women, men, and the economic consequences of divorce: Evidence from Canadian longitudinal data. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 30(2), 205–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.1993.tb00173.x.

Geisler, E., Kreyenfeld, M., & Trappe, H. (2016). Erwerbsbeteiligung von Müttern und Vätern in Ost- und Westdeutschland: Strukturstarre oder Trendwende? [Labour force attachment of mothers and fathers in East and West Germany: Structural rigidity or trend reversal?]. Archiv für Wissenschaft und Praxis der sozialen Arbeit, 47(2), 4–15.

Giesselmann, M., & Windzio, M. (2012). Regressionsmodelle zur Analyse von Paneldaten [Regression models for ananlysing panel data]. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Hammerschmid, A., & Rowold, C. (2019). Gender Pension Gaps in Europa hängen eindeutiger mit Arbeitsmärkten als mit Rentensystemen zusammen. [Gender pension gaps depend more strongly on labor markets than on pension systems]. DIW Wochenbericht Nr. 25/2019. https://doi.org/10.18723/diw_wb:2019-25-1.

Hancioglu, M., & Hartmann, B. (2014). What makes single mothers expand or reduce employment? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9355-2.

Hauser, R., Burkhauser, R. V., Couch, K. A., & Bayaz-Ozturk, G. (2016). Wife or Frau, women still do worse: A comparison of men and women in the United States and Germany after union dissolutions in the 1990s and 2000s. Working Paper 2016–39: University of Connecticut, Department of Economics.

Herbst, A., & Kaplan, A. (2016). Mothers’ postdivorce earnings in the context of welfare policy change. International Journal of Social Welfare, 25(3), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12205.

Himmelreicher, R. K., & Stegmann, M. (2008). New possibilities for socio-economic research through longitudinal data from the Research Data Centre of the German Federal Pension Insurance (FDZ-RV). Journal of Contextual Economics: Schmollers Jahrbuch, 128(4), 647–660.

Hübgen, S. (2018). Only a husband away from poverty? Lone mothers’ poverty risks in a European comparison. In L. Bernardi & D. Mortelmans (Eds.), Lone parenthood in the life course (pp. 167–189). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63295-7_8.

Jarvis, S., & Jenkins, S. P. (1999). Marital splits and income changes: Evidence from the British household panel survey. Population Studies, 53(2), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720308077.

Keck, W., Radenacker, A., Kreyenfeld, M., & Mika, T. (2019). FDZ-RV scientific use file: Statutory pension insurance accounts and divorce. [Unpublished Manuscript].

Kessler, D. (2018). The consequences of divorce for mothers and fathers: Unequal but converging? LIVES Working Papers, 71, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.12682/lives.2296-1658.2018.71.

Kreyenfeld, M., & Mika, T. (2006). Analysemöglichkeiten der Biografiedaten des “Scientific Use File VVL 2004” im Bereich Fertilität und Familie. [Analytical capacities of biography data of the “Scientific Use File VVL 2004” in the field of fertility and family]. Deutsche Rentenversicherung, 9–10, 583–608.

Leopold, T. (2018). Gender differences in the consequences of divorce: A study of multiple outcomes. Demography, 55(3), 769–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0667-6.

Lewis, J. (1992). Gender and the development of welfare regimes. Journal of European Social Policy, 2(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879200200301.

Lewis, J., & Ostner, I. (1994). Gender and the evolution of European social policies. ZeS Working Paper, 94(4).

Madero-Cabib, I., & Fasang, A. E. (2016). Gendered work-family life courses and financial well-being in retirement. Advances in Life Course Research, 27, 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2015.11.003.

OECD. (2017). Dare to Share – Deutschlands Weg zur Partnerschaftlichkeit in Familie und Beruf. [Dare to share – Germany’s experience promoting equal partnership in families]. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264263420-de.

Poortman, A.-R. (2000). Sex differences in the economic consequences of separation: A panel study of the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 16(4), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/16.4.367.

Raz-Yurovich, L. (2013). Divorce penalty or divorce premium? A longitudinal analysis of the consequences of divorce for men’s and women’s economic activity. European Sociological Review, 29(2), 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr073.

Smock, P. J. (1994). Gender and the Short-Run Economic Consequences of Marital Disruption. Social Forces, 73(1), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/73.1.243.

Tamborini, C. R., Couch, K. A., & Reznik, G. L. (2015). Long-term impact of divorce on women’s earnings across multiple divorce windows: A life course perspective. Advances in Life Course Research, 26, 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2015.06.001.

Trappe, H., Pollmann-Schult, M., & Schmitt, C. (2015). The rise and decline of the male breadwinner model: Institutional underpinnings and future expectations. European Sociological Review, 31(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv015.

Uunk, W. (2004). The economic consequences of divorce for women in Europe: The impact of welfare state arrangements. European Journal of Population, 20(3), 251–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-004-1694-0.

Van Damme, M., & Kalmijn, M. (2014). The dynamic relationships between union dissolution and women’s employment: A life-history analysis of 16 countries. Social Science Research, 48, 261–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.06.009.

Van Damme, M., Kalmijn, M., & Uunk, W. (2009). The employment of separated women in Europe: Individual and institutional determinants. European Sociological Review, 25(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn042.

Zagel, H. (2014). Are all single mothers the same? Evidence from British and West German women’s employment trajectories. European Sociological Review, 30(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct021.

Zagel, H. (2015). Understanding differences in labour market attachment of single mothers in Great Britain and West Germany. In J. Goebel, M. Kroh, C. Schröder, & J. Schupp (Eds.), SOEP papers on multidisciplinary panel data research. Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung.

Acknowledgments

This book chapter originates from work for the project “Divorce, separation and the economic security of women in Germany” (Az. Ia4-12141-1/20), funded by the Fördernetzwerk Interdisziplinäre Sozialpolitikforschung (FIS) of the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Radenacker, A. (2020). Changes in Mothers’ Earnings Around the Time of Divorce. In: Kreyenfeld, M., Trappe, H. (eds) Parental Life Courses after Separation and Divorce in Europe. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 12. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44575-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44575-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-44574-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-44575-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)