Abstract

This chapter offers a philosophical diagnosis of the challenges that medicine is facing, regarding medically unexplained symptoms and complex illnesses. We propose that a crucial problem comes from applying a Humean regularity theory of causality, in which a cause is understood as something that always provokes the same effect under ideal conditions, to the clinical reality, where no ideal condition, or average patient, can ever be found. A dispositionalist understanding of causality proposes instead to start from the particular and unique situation of the single case in order to understand causality. The medical evidence, including causally relevant evidence, must then be generated starting from the single patient. This includes not only the patient’s medical data, but also the patient’s condition, narrative and perspective. This is fundamental in order to generate causal hypotheses about the complex situation and all the dispositions that influence the medical condition. Ultimately, evidence from the clinical encounter could assist the design of experiments both in the lab and in the clinics. The best approach to causality, we argue, is to use a plurality of methodologies. We also explain how, when starting from a dispositional theory of causality, heterogeneity, unexpected results and outlier cases actually represent an epistemological advantage, instead of an obstacle, for the causal enquiry.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

In Western countries, most persons asking their regular general practitioner for help and advice share certain common characteristics: they show up repeatedly and over time, although at varying intervals and for a variety of reasons; they present complex health problems which may involve acute maladies but often include chronic, somatic and/or psychiatric distress; at the same time, they may seek advice for medically unexplained or undefined malfunctions, which may be equally if not more problematic and incapacitating than the supposedly well-defined diseases or disorders…

Experienced GPs are aware of patterns of sickness, both within groups of patients and in individuals, that seem to point to sources of bad health beyond the medically defined horizon of causality. These patterns are complex and transgress such medical dichotomies as “somatic” and “mental”. They are specific in the sense that they represent clusters of diseases or malfunctions, which apparently have such common “causes” as inflammation, infection or invasion (in the sense of tumour growth). This, however, leads to the next level of relevant questions, those regarding the “cause” or “causes” of a dangerously compromised immune system manifesting in systemic inflammations, repeated infections or multiple invasive processes. Here, a rapidly growing documentation highlights the medical significance of context, offering ways of understanding the detrimental impact of lifetime adversity on health.

Anna Luise Kirkengen, ‘Map versus terrain?’, CauseHealth blog (https://causehealthblog.wordpress.com/2017/04/18)

1 The Clinical Challenge of Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS)

Healthcare professionals are regularly faced with patients who suffer from multiple conditions at the same time. How exactly these conditions relate is not a straightforward question and, in some cases, the causes themselves remain a mystery. Patients who experience what are commonly referred to as medically unexplained symptoms, or MUS, exhibit a number of symptoms that appear together but do not seem to have a single, common biomedical cause.

The increase in medically unexplained symptoms represents an emerging problem in European and other industrialised countries. ‘Medically unexplained’ refers to the lack of explanatory pathology. Researchers have not been able to find a common set of causes, a definite psyche-soma division, or even clear-cut classifications for these symptoms. The problem with these conditions not being explained generally means that the biological causes of the symptoms are unknown. Some of the causal factors involved might be known, but the underlying mechanisms are not understood. In general, no adequate psychological or organic pathology can be found, and medical examination is unsuccessful in giving a diagnosis to the symptoms (Eriksen et al. 2013a). Each patient seems to have a unique combination of symptoms and a unique expression of the condition, and medical uniqueness appears to be the rule rather than the exception. A problem with this is that evidence from population studies are of limited use for these patients.

That no causal explanation is found for a condition is not a rare or unfamiliar phenomenon. MUS have been estimated to account for up to 45% of all general practice consultations, and a study from secondary care suggests that after 3 months, half of the patients received no clear diagnosis (Chew-Graham et al. 2017). It is difficult to give a precise number, however, since there is no general agreement over what counts as a MUS. Some examples are chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, low back pain, multiple chemical sensitivity, general anxiety disorder, tension-type headache, post-traumatic stress disorder and fibromyalgia. Some other conditions lack a commonly accepted diagnosis, or even a clear definition, yet they seem to be increasingly common, in some cases almost mass phenomena. Another example of a medically unexplained condition is burnout, which indicates a pathological condition somehow connected with severe stress and work overload. Psychotherapist Karin Mohn Engebretsen has dedicated her doctoral research to the analysis of burnout as a challenge for the current scientific paradigm. She writes:

As a Gestalt psychotherapist, I have seen an increasing number of individuals over the last fifteen years that experience themselves as burned out. This fact has triggered my interest to explore the phenomenon further. Burnout is a medically unexplained syndrome (MUS). As with other MUS, there is a tendency to assume a narrow perspective to focus on problems related to psyche or soma as pathologies located exclusively within the patient. Research has mainly looked for clear-cut one-to-one relations between cause and effect. These relationships are however difficult to find in complex syndromes.

Burnout might instead be seen as a reaction to complex causes and a broad contextual setup, but unfortunately, such point of view has only been marginal. Consequently, medical professionals are faced with comprehensive challenges due to factors such as lack of a causal explanation, lack of diagnostic descriptions and lack of a treatment or medical interventions.

Karin Mohn Engebretsen, ‘Are we satisfied with treating the mere symptoms of medically unexplained syndromes?’, CauseHealth blog (https://causehealthblog.wordpress.com/2017/03/27/are-we-satisfied-with-treating-the-mere-symptoms-of-medically-unexplained-syndromes/)

As pointed out by Engebretsen, healthcare professionals who deal with a person experiencing burnout will face some deep theoretical and methodological issues (Engebretsen 2018; Engebretsen and Bjorbækmo 2019). For instance, is a response to stress overload to be considered a medical condition? Should it be seen as one of the symptoms, or one of the causes? How to distinguish burnout from other well-defined pathologies with similar symptoms, such as depression? And, even more problematically: how to act when no clear-cut causality can be found, given that curing a disease means to counteract its causes?

The problem of understanding MUS could be interpreted as an empirical matter, to be solved by doing more of the same. On this view, more observation data, RCTs, symptom measurements and classification could ultimately lead to a clearer understanding of these conditions. Given the dispositionalist framework of CauseHealth, however, we see MUS as a symptom of some deeper problems in current medical thinking (Eriksen et al. 2013b). Specifically, the problem of MUS seems to point to a philosophical challenge, namely: how to understand causality in cases of complexity, individual variation and uniqueness.

The challenge of dealing with MUS, even conceptually, played a central role in the CauseHealth project. We started from the idea that the problem of MUS is a practical challenge for medicine, but one that has a philosophical source. MUS are troubling and chronic conditions that are often depicted as outliers: atypical illnesses where standard causal explanation fails. From the dispositionalist perspective, however, every patient is to be considered, in one way or another, an outlier. Recall that dispositionalism is a singularist theory of causality (see Anjum, Chap. 2, this book). Since causality happens in the single case, we need to be armed with strategies to look for it in the single patient, while at the same time making use of general medical and other theoretical knowledge. The problem of dealing with MUS, then, is rooted in a deep conceptual challenge of the current paradigm. Finding a way to deal with these conditions epistemologically was therefore seen as the key to getting a better grasp of medicine as a whole. If we understand the problem of MUS, we thought, we will better understand the problem of investigating causes of health and illness generally.

In this chapter, we take a closer look at the challenge that causal uniqueness represents, not only for the healthcare professional having to deal with MUS and other complex conditions, but also for the whole medical paradigm. We make a ‘philosophical diagnosis’ of the problems of dealing with causal uniqueness in the clinical encounter: they come from a positivist, or Humean, understanding of causality. We then explain how an ontological turn toward a dispositionalist starting point should help us deal better with the challenging features of MUS: causal complexity, heterogeneity and medical uniqueness. From a dispositionalist perspective, we will argue, these features should not be seen as problems for causality, but instead as typical for it, and therefore as opportunities to understand causality better.

2 The Problem of Uniqueness

While in medicine and healthcare the default assumption is that all patients are different, causation itself is sought as something that is robust throughout different contexts. This leaves us, in effect, to search for same cause and same effect:

-

Same symptoms, same diagnosis (diagnostics)

-

Same diagnosis, same intervention (standardised treatment)

-

Same intervention, same effect (tested though RCTs)

Although individual variations are acknowledged, they are nevertheless not the focus when trying to establish causality. Instead, variations can be used to form more fine-grained classifications or sub-groups, where one again looks at what is the same. In other words, uniqueness is considered an obstacle when one tries to establish causality scientifically.

This contrasts with the dispositionalist framework. No two individuals will have exactly the same combination of causal dispositions or propensities. Even if there are some dispositions that we share, such as gender, age or medical condition, so many other dispositions will be different from one individual to another. Grouping patients into more relevant sub-groups will plausibly tend to give a more appropriate average than broader and unspecific sub-groups. We know, however, that not all pregnant women in their thirties or all men over 60 with hypertension are identical in all their dispositions – or even sufficiently identical. Which of these dispositions are taking part in the single causal process that we are investigating? This is a question that cannot plausibly be answered with certainty. We will therefore never be sure of whether or how precisely a sub-population represents the dispositions in place in the individual process. A frequentist approach, we have said, will either have to overlook this knowledge gap or try to further specify the relevant sub-group (see Rocca, Chap. 3, this book). Eventually, however, one might end up with a sub-group with only one member: the N = 1 group consisting of the single patient. Still, the problem remains how to establish, predict and explain causality for a patient for whom no suitable, or suitable enough, sub-population can be found.

This is one reason why MUS represent a methodological challenge for medicine and healthcare. In the current paradigm, the best way to establish causality is by showing that the same cause makes a difference toward the same effect in sufficiently similar contexts. To make this clear, think back to the principle of randomised controlled studies (RCTs), as explained above in Sect. 3.2. We saw here that RCTs are considered to be the best way to establish causality within the current paradigm of evidence based medicine and practice, and they are designed to test for a type of homogeneity: common causes and common effects. This means that even though there is plenty of individual variation within the clinical study, these variations are not what the RCT is designed to study or establish. On the contrary, such individual variations are supposed to be shielded off through randomisation, so that test group and control group are overall very similar. With RCTs, we look for the overall effect of an intervention in the test group, compared with the overall effect in the control group. The intervention is then the same, and the effect tested is the same.

RCTs thus target same cause (intervention), same effect (outcome). This is completely in line with Hume’s regularity theory of causality (Hume 1739), but it doesn’t acknowledge the dispositionalist perspective that causes as dispositions are intrinsic properties: they tend to manifest, but not always. They tend to make a statistical difference, but not always. They tend to produce one effect, but not always the same (Anjum and Mumford 2018, see also Anjum, Chap. 2, this book). RCTs are great tools to detect manifestations that make a difference at population level, but they are not useful for studying dispositions that remain mostly unmanifested, and which tend to manifest themselves in single and causally unique cases. We see, then, that the problem of MUS is not an isolated one, but one that has its roots in the Humean influence on medical thinking about causality that can be summarised in the following three points:

-

1.

A and B are observed repeatedly (empiricist criterion: causality must be detected empirically)

-

2.

Whenever A, B, under some normal or ideal conditions (regularity criterion: same cause, same effect)

-

3.

B happens because of A (monocausality criterion: one cause, one effect)

-

4.

If not B, then not A (falsification criterion: a difference in effect must mean that there is a difference in the cause).

For A to be the cause of B, these conditions must be met, according to the Humean notion of causality. Medically unexplained symptoms, however, typically fail to meet one or several of these criteria, which is why we cannot say that a medical cause has been found.

Let us show this by considering the case of unspecific lower back pain. Qualitative studies show that in the clinical dialogue, patients usually associate this condition with an episode such as bending or lifting. Patients mention that they felt sudden pain during a certain activity, and that they have been in pain ever since (Jeffrey and Foster 2012). There is, in the clinical encounter, a deep intuition of a causal link between a certain accident, or event, and the condition. However, this cannot be epidemiologically confirmed. There is much literature on unspecific lower back pain, but no systematic association has been shown with mechanical factors (lifting, standing, walking, postures, bending, twisting, carrying, and manual handling) nor with activity levels, obesity, smoking, mood, or genetic factors (see Eriksen et al. 2013b for a review of the epidemiological evidence). None of these causal factors seem to fulfil the Humean criteria of regularity, repeatability and falsification. Epidemiologically, and according to Humean criteria, therefore, there is no clear cause of unspecific lower back pain, despite decades of research. And yet, single patients tend to be able to indicate a cause, at least as they experience it. This and similar cases of medically unexplained conditions represent a challenge for any attempt at standardisation or universal approach to cure and healthcare.

2.1 The Patient Context: What Was There Before

From a healthcare perspective, one does not expect that the same cause will give the same effect in different individuals. Individual responses depend on what else was there already, as part of the patient’s own context. A person who is at a vulnerable stage in life might be more disposed to an infection than a person who is at a more robust stage, for instance. This is, one can say, elementary clinical knowledge. Still, this real-life complexity becomes a problem for causal understanding when we try to analyse it using the Humean criteria. Dispositionalism instead acknowledges complexity and context-sensitivity as basic features of causality.

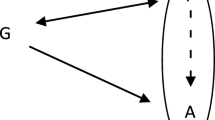

We can represent the different impact of one causal disposition in different patients with the vector model of causality (Mumford and Anjum 2011), where each vector represents one causal disposition in place, and the line T represents the threshold for the manifestation of an effect, as explained in Chap. 2. In the vulnerable patient (Fig. 4.1), the situation is much closer to the threshold of illness than in the robust case (Fig. 4.2). This means that even a minor burden on health can have a major impact, because it pushes the situation over a threshold. This is a well-known phenomenon. We often speak of the straw that broke the camel’s back, which was simply the final straw adding to the already heavy burden. A cause might then be simply what tips the situation over the threshold, which seems far too insignificant if we ignore what was already there before it.

Let us say that the two patients get affected by influenza, and after that only one of them develops a chronic burnout syndrome, while the other recovers normally. From a Humean point of view, this does not tell us much about the causal role of the influenza for the onset of burnout. Instead, we would need to check whether there are other patients as similar as possible to the patient who develops burnout symptoms after getting influenza (same cause – same effect, all else being equal).

From a dispositionalist perspective, however, looking further into cases of individual variation and context-sensitivity represents a chance for understanding something about the underlying causal story. When the same cause gives different effects in two different contexts, we might learn something new. Clearly, to do that, it does not help to focus on the single cause or the single effect. Instead, one should try to understand what was already there in the two different contexts, disposing toward or away from health and illness. This type of reasoning needs to be qualitative and explanatory, in order to be fruitful. By trying to understand all the causal dispositions in place, and the way they interact with each other, we build a causal explanation – a hypothesis – for how and why things went the way they did.

Note that the causal explanation, or causal mechanism, although being based on empirical evidence, is not itself something we can observe directly. This is why Hume’s empiricist approach does not include causal theories or explanations but sticks to what can be observed and counted. On the contrary, the search for evidence of a plausible causal explanation (which dispositions are present, how they interact and manifest) is at the core of the dispositional approach. It is also crucial for any scientific theory, including in medicine and healthcare.

Humean and empiricist influence have been strong, not only in research, but also in the clinic. There tends to be the expectation, at least in the implementation of some health policy and clinical guidelines, that patients with the same diagnosis should respond similarly to the same treatment. Personalised medicine and system medicine have been rising trends and can be seen as attempts toward a more dispositionalist approach: aiming to fit the treatment to the patient’s own dispositions. However, these approaches are mainly focussed on genetic or molecular dispositions and have less focus on psycho-social or ecological complexity (Vogt et al. 2014). This will be discussed in Chap. 5 when we look at the biomedical model of medicine.

Allowing the features of uniqueness and complexity to guide the clinical encounter, we should focus less on what is the same and more on what is different and unique for this particular patient, also for causal matters.

Simply put…

Humeanism refers to David Hume’s regularity theory of causality, which emphasises features such as empiricism, observable features (data), mono-causality, repetition and same cause – same effect. Probabilities are understood as generated statistically (frequentism).

2.2 Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Causal Inquiry

What exactly do we mean by a qualitative analysis? And how should such analysis help us look for causal explanations? How does this approach contrast with quantitative analysis and the search for same cause – same effect? In our philosophical framework, we have a particular take on what should count as qualitative and quantitative approaches to causal inquiry. Qualitative approaches will be concerned with the investigation of many types of information in few tokens, and with how these relate, and under which conditions. In contrast, quantitative methods will look for few types of information that are in common for many tokens (see also Anjum and Mumford 2018: 106). Notice that from the dispositionalist perspective, qualitative research can advance causal understanding and theory, and is not limited to the purposes of meaning and lived experience (see Sect. 4.4). Qualitative research, in our definition, encompasses scientific enquiry of a phenomenon, as long as such enquiry aims to understand a causal process, while quantitative research aims to identify the numerical relationship between variables. A qualitative approach, in our understanding, might involve numerical values, but is always process-oriented, aims to generate theoretical understanding, it is adapted to the most relevant context of application of the research, and it happens in-situ, often in a participatory way.

An example might help illustrate this distinction.

For example, a recent large study compared the whole-genome sequences of participants with food allergy to peanuts, egg or milk with non-allergic participants (in total almost 3.000 individuals were included)[…] The results showed statistically significant DNA modifications in specific loci of the genome, indicating that these loci are probably part of the genetic component of the food allergy. Other information about the participants were age, sex, ancestry (European or non-European), results of food allergy tests, and presence of other allergy-related disease. While such a horizontal analysis has big statistical power, it relies on the preliminary selection of a limited amount of variables to compare. The selection is informed by existing knowledge and working hypothesis (in the case of this study, that allergies have a genetic component). Additionally, it is dictated by practical considerations since these studies include a large amount of participants. While results are statistically robust, their contribution is limited to a small part of the picture. In fact, genetic predisposition is only one of many actors for the onset of a condition.

Let us imagine using a larger filter to evaluate which contextual variables to include in the analysis. We might then consider a complete range of clinical factors, blood levels, present and former state of health, dietary habits, lifestyle, polypharmacy, psychological health, addictions, traumas, including as much information as possible about the unique context that was exposed to the allergen. This would necessarily restrict the comparison to a limited number n of patients […].

The experiment would then be a qualitative, rather than quantitative, analysis. It would have a different aim: the aim of identifying not a single element that is frequently involved, but enough elements to suggest a pattern, or offer an explanation that is valid in this specific instance. Such explanation might fall outside the boundaries of existing knowledge and suggest an advance in the overall understanding of causal mechanisms. Finding out whether these hypotheses are generalizable and to which extent, belongs to a subsequent stage of research. (Rocca 2017: 117)

Simply put…

In our framework we propose that qualitative approaches to causal inquiry collect many types of information in few tokens and look for a theoretical understanding of how these relate causally in a particular context. Quantitative approaches, instead, look for few types of information in many tokens, and aim to identify numerical correlations among them.

2.3 Dispositional Take On Perfect Regularity: Is It Causality or Something Else Entirely?

A dispositionalist denies that causality is something that produces perfect regularity between cause and effect. Instead, causality is understood as tendencies, where the cause A only tends or disposes toward the effect B. So even if A is present, B can still be counteracted by adding an interferer I (Mumford and Anjum 2011). All of medicine is premised on this idea. Even if one has not yet been able to find a treatment, the expectation is still that if one can understand the causal mechanisms of the disease, it should be possible to counteract or interfere with the causal process in one way or another.

This has a surprising consequence. If there were to be a perfect correlation of A and B, where no changes in context could influence the situation in any way, a dispositionalist should become suspicious. Is this a case of causality after all? Or could it be a case of classification or identity? For instance, all humans are mortal. And although scientists are still working on ways to counteract and delay death, one could still argue that any immortal being could not be human. So even if there were a human-like immortal species in the future, we might say it’s not the same as a human.

Now take a medical case. It is said that Down syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21. But is this the right way to phrase it? As long as a person has the extra chromosome, they will be diagnosed with Down syndrome. If Down syndrome is then defined as the condition of having the third copy of chromosome 21, then, of course, there will be a perfect regularity between A and B. But the reason why we have the situation that whenever A then B, is that A is defined as B. In that case, A = B. This does not mean that there is no causality going on here. The causal relationship would then be between the extra chromosome and the expression of the condition, which vary in degree from individual to individual. The symptoms of Down syndrome are then caused by the extra chromosome, and will be manifested in different ways in different individuals. Whether someone has the syndrome will correlate perfectly with whether they have the extra chromosome, without any individual variations. This suggests that it is an identity relation, not a causal one.

Perfect regularities, on the dispositionalist perspective, could be produced by other types of truths than causal ones, such as classification (all humans are mammals), stipulation (all electrons are negatively charged), identity (bachelors are unmarried men) or essence (humans are mortal). In contrast to these types of claims that have the categorical form ‘All As are Bs’, causal claims are about what happens under certain conditions. A causal claim is therefore a hypothetical or conditional matter: ‘If we do x to y, would z follow?’. To say that ‘All As are Bs’ is to make a statement about how to categorise A and B with respect to one another. In contrast, when we ask whether A is a cause of B, we want to know whether and to what degree A is able to bring about B or at least contribute to the production of B.

Note, however, that if A is indeed a cause of B, a dispositionalist should not expect that all instances of A will actually and successfully produce B. Causes, as dispositions, are irreducibly tendential. There is never more than a tendency of A to produce B. As discussed in Chap. 2, a dispositional tendency can be stronger or weaker. Someone can be more or less vulnerable, more or less violent and more or less allergic to peanuts, for instance. We also saw that dispositional tendencies give rise to individual propensities, rather than statistical frequencies (see Rocca, Chap. 3, this book). The degree of tendency does not determine how often a disposition will manifest, but only how strong the intrinsic disposition is in this individual situation. For instance, if we want to know how fertile someone is, one should do a sperm count rather than counting the number of offspring. The higher the sperm count, the stronger the disposition of fertility. It does not follow from the strong fertility that one will eventually have a lot of children. It also does not mean that other people with the same sperm count will have many children.

We see, then, that a dispositionalist should not expect perfect regularity of cause and effect. Instead, a dispositionalist should be sceptical if there is a perfect correlation that is insensitive to contextual change. Could it be a case of identity, classification or essence instead? Or have we already stipulated some ideal conditions or idealised model under which the cause would always produce the effect? Either way, we cannot expect that causality will manifest itself in perfect correlation in a real-life situation such as what we encounter in the clinic. The only way we can expect that the same cause will always produce the same effect, is by stipulating some average, normal or ideal patient with average, normal or ideal responses. In the clinic, however, such encounters are rare.

3 An Important Lesson from Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS)

We saw that medically unexplained symptoms remain a challenge for the healthcare profession because of some problematic features: causal complexity, heterogeneity and medical uniqueness. If this is a problem for establishing causality, then we got a much bigger problem than MUS. In most health conditions, there is at least some complexity of causes, some individual variation and some unique factors. This is the case for cancer, heart disease, obesity, Alzheimer’s, hypertension, diabetes, stress-related symptoms and many other conditions. Although these conditions are not medically unexplained, because there is some common pathology, they are still complex disorders with multiple causes.

All conditions that are caused by a combination of genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors, will have many unknown causes and many causes that are unique to that patient (Craig et al. 2008). And since each patient has a unique combination of biological, social and psychological factors, complex diseases are very likely to be heterogeneous (Hellhammer & Hellhammer 2008). From the dispositionalist perspective, therefore, there is a lot more in common between medically unexplained and medically explained conditions than what is normally assumed. What can we learn from this?

First of all, this means that our understanding of illness cannot rely solely on single or few physical, or biomedical, homogeneous causes. When a common physical cause of illness is found, such as the bacterium helicobacter pylori (HP) for peptic ulcer, it can quickly become the main focus of medical attention while other causes gain the status of ‘background conditions’. This is the case with lifestyle factors such as stress and diet, for instance, which were thought to cause ulcer before the discovery of HP, and have been since decades at the periphery of the therapeutic focus (de Boer and Tytgat 2000). Looking at this case in more detail, however, it has been estimated that at least half the world’s population is infected by the HP bacterium, but most of those infected never develop an ulcer (Go 2002). We see then that although one causal factor might be the necessary condition for the development of a pathology, whether such pathology is triggered, how it is expressed, when, and to what degree, will be influenced by a plethora of other causal factors. When dispositionalism emphasises causal complexity, it means that a mono-causal focus on a common physical cause will necessarily mean that we miss out on some of the causal story, if not most of it (Copeland 2017). This is why CauseHealth proposes that the challenging features of MUS should be treated as the norm, rather than be dismissed as marginal and atypical. All illness is complex, and many of the causal factors will be unique to the individual case.

This has a practical consequence, not only for research, but also for the clinical encounter. It means that by understanding the complexity and uniqueness of the patient’s situation, one will find a number of factors that might be influencing their condition positively or negatively. And although the known biomedical factor (such as the HP bacterium) leaves little wiggle-room other than the standard medical interventions, many of those other influences (lifestyle, diet, stress) are usually important to target too, and might be even easier to counteract. Being aware of these other dispositions that are causally relevant for the health condition, and understanding how exactly they influence the experience of health and illness, can then empower both patient and clinician. The patient might get a better understanding of what caused their condition, but that is not all. The patient might also be able to influence and work with some of these dispositions, thus getting a better sense of control and agency with respect to their own health (see Price, Chap. 7, this book).

3.1 We Need Many Methods to Establish Causality

Searching for and establishing causes in the dispositionalist framework is not something that can be done using only one single method, such as RCTs (Rocca and Anjum 2020a). In CauseHealth, we have argued that causal enquiry requires a plurality of methods, each of which picks out one or more symptoms of causality (for details, see Anjum and Mumford 2018). In an open letter to BMJ Evidence Based Medicine, co-signed by 42 clinicians and philosophers from international and interdisciplinary research networks working specifically on causality in medicine, we urged that EBM approaches widen their notion of causal evidence:

The rapid dominance of evidence based medicine has sparked a philosophical debate concerning the concept of evidence. We urge that evidence based medicine, if it is to be practised in accordance with its own mandate, should also acknowledge the importance of understanding causal mechanisms… Our research has developed out of a conviction that philosophical analysis ought to have a direct impact on the practice of medicine. In particular, if we are to understand what is meant by ‘evidence’, what is the ‘best available evidence’ and how to apply it in the context of medicine, we need to tackle the problem of causality head on… In practice, this means understanding the context in which evidence is obtained, as well as how the evidence might be interpreted and applied when making practical clinical decisions… It also means being explicit about what kind of causal knowledge can be gained through various research methods. The possibility that mechanistic and other types of evidence can be used to add value or initiate a causal claim should not be ignored. (Anjum et al. 2018: 6)

How exactly would this work if we assume a dispositionalist understanding of causality?

In dispositionalist terms, if we want to establish a causal link between A and B, this corresponds to establishing whether A has intrinsic dispositions that, in combination with other dispositions, can eventually produce B. Different methods will have some strengths and some limitations for the purpose of finding such intrinsic dispositions. For instance, RCTs are good for picking out which factors make a difference, or raise the probability of an effect, on population level. But positive results from RCTs do not guarantee that this difference-making or probability-raising happened because of some intrinsic disposition in the test group, since that would require a further theoretical explanation. RCTs are also less suitable for testing the contextual complexity of mutual manifestation partners, since the focus is on one or few particular interventions (for which there can be a control or comparison) and one or few outcomes. Other methods could be more suitable than RCTs when we are searching for dispositions or manifestations that are too rare to show up in statistical approaches. In this case, retrospective case-control studies allow us to study outlier cases or very rare conditions. However, since these studies are designed to find common dispositions for the same outcome across different contexts, any non-common dispositions contributing to the outcome in the individual cases will not be targeted.

These are just two examples, but all scientific methods will similarly be designed to test some specific symptoms of causality, while other symptoms will fall outside the scope of the test. The problem is if we think that one method should be a perfect test for picking out causality. Such a perfect test might require that we operationalise causality. This means that we simply identify the phenomenon of causality with the method we use to test it. Examples of operationalization can be to identify temperature with the measure shown on the thermometer, depression with a series of specific behaviours, or cancer with a positive screening. In the case of causality, operationalisation might correspond to saying that causality is nothing more than the statistical difference of effect between experimental group and control group, as detected for instance by a positive RCT.

Operationalisation of causality would be a perfectly acceptable strategy for a strict empiricist, since they would reject any ontological reality that cannot be observed. Indeed, Hume already stated which observable features would be necessary and sufficient for calling something causality: constant conjunction, temporal priority and contingency. From a dispositionalist perspective, however, there would be no one perfect test of causality that could empirically pick out all its features. A cause will tend to make a difference, but there is no perfect overlap between difference-making and causality. A cause will also tend to produce some regularity, but again there is no perfect overlap (Anjum and Mumford 2018).

Embracing the idea of methodological pluralism – that we need more than one method to establish causality – we will now look at another method for obtaining more qualitatively rich causal information, namely patient narratives. We make a case for the epistemological importance of obtaining detailed information from the patient herself when searching for causal explanations of illness. As a methodology, rich patient information allows the detection of relevant dispositions that are uniquely combined in this individual patient (biomedical, biographical, lifestyle, and life situation), and that could be relevant for their condition or the treatment. This type of knowledge should therefore not be ignored if we understand causality in a dispositionalist sense.

4 Patient Narratives as a Way Forward

We have said that the clinical encounter can contribute to improving the causal understanding of health and illness, in the dispositionalist sense. We saw that, in order to evaluate individual propensities, one needs to learn as much as possible about the dispositions and interactions in place in the particular case of interest (see Rocca, Chap. 3, this book). In the case of healthcare, this means learning more about the patient and their context. From the dispositionalist perspective, therefore, the clinical encounter has a pivotal role to play for advancing our understanding of the causal story behind illness and suffering. Notice that we do not talk only about the clinical examination, which is just a part of the encounter. In the examination, the clinician collects biological and medical information, while in the encounter she meets the patient as a person with a unique biography, context and story. Osteopath Stephen Tyreman argues that a whole person centred approach is crucial for understanding illness and symptoms.

What do symptoms tell us about the person rather than their disease? Symptoms are key elements in a person’s narrative about illness in general and their illness in particular. We want to know what symptoms mean, what they tell us (in a narrative sense) about what has happened and what the future will be like. As much as indicating a particular biological problem, symptoms reflect how we live—the smoker’s cough, the athlete’s muscle ache, the workaholic’s tiredness, the sedentary person’s breathlessness, and so on. Are these indicators of actual or potential disease or is disease a possible emergent outcome of such behaviour? Many symptoms we accept as normal and healthy—the discomfort of pregnancy and childbirth or the stiffness after a day’s physical activity, for example. In other words, do symptoms tell us more about a person’s living before they tell us about disease?

Stephen Tyreman, ‘More on symptoms’, CauseHealth blog https://causehealthblog.wordpress.com/2017/04/03/more-on-symptoms/

How exactly can the clinical encounter contribute to improving causal knowledge of the dispositions in place? The way modern medicine is generally practiced does not seem to leave much space for understanding the full complexity of the causal situation of patients. In the last century, for instance, the objectivity of doctors’ reports was emphasised. Physicians have to ‘translate’ patient reports and accounts of their condition into a standard medical language. This is not in itself a limitation. The problem is when such standard medical language is seen as the only information of significance, while the information that is excluded, about the patient’s version and interpretation of their condition, is considered irrelevant for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment (for an example of this, see Kirkengen, Chap. 15, this book).

There is an alternative to this orthodox practice that is more in line with the dispositionalist framework. This is to use patient narratives as an essential part of the evidence available (Greenhalgh and Hurwitz 1998). We see this in a recent development in medical humanities, called narrative medicine, although it would not generally be considered as causal evidence. Instead, patient narratives are often dismissed as causally irrelevant because of their anecdotal nature, a story from a single unique patient. In CauseHealth we have promoted the importance of qualitatively rich information about the dispositions provided by the local context (the patient), based on causal singularism (medical uniqueness), context-sensitivity (heterogeneity) and genuine causal complexity (holism and emergence) (Rocca and Anjum 2020b). The main idea that we here want to emphasise is that the subjective and embodied experience as told by the patient, traditionally seen as a possible obstacle to the objective medical diagnosis, is in fact a powerful tool for exactly that purpose. Patients, in their narrations, choose to include some information and to omit some other. A narration also gives meaning to the medical events, and such meanings will most probably vary depending on the narrator. Crucially, there is a reason for such interpretations and this reason is not possible to capture in the standard medical story.

We can illustrate this point with an example from the treatment of morbid obesity. Guidelines recommendations for this condition are based on knowledge about the biological mechanisms underlying normal and irregular food intake and appetite. Recommended treatments consist in lifestyle modification programs, pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery. Depending on the single patient and her standard medical story, physicians can choose the treatment that is thought to be best suited for the patient. Although all these interventions could result in some modest to good improvement, there is a systemic tendency toward re-gain of weight in the vast majority of the patients, provoking frustration in both clinicians and patients (Karmali et al. 2013).

What might happen if the standard medical story is accompanied by a thorough analysis of patient narratives? One answer comes from general practitioner Kai Brynjar Hagen. He has been working for many years as a senior consultant at a Norwegian regional centre for morbid obesity. His job is to assess the patients before bariatric surgery, which is the last step in the therapy of obesity. The assessment included interview sessions with patients. During these sessions, Hagen collected the stories of their embodied, lived illness experience. He came to the hypothesis that what practitioners treat at the moment (energy homeostasis imbalance, food intake, lifestyle) are in the majority of cases only the symptoms or the condition, and not what he understands as the real or core cause of obesity. By taking the time to listen to his patients, asking them about their childhood, whether they enjoyed school, how their family life is and how they feel about their life in general, he observed that many of his patients had experienced some sort of emotional traumas that affected, triggered or worsened their eating disorder. His worry is that if these biographical aspects are ignored and obesity is treated as a purely biomedical condition, to be solved by eating less, one will fail to target the true cause of the problem (see Hagen, Chap. 10, this book). This could also explain why the current treatments for obesity in many cases fail and why there is a tendency toward suicide among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery (Lagerros et al. 2017; Neovius et al. 2018; Castaneda et al. 2019).

When overlooking important causes of obesity, such as the dispositions of trauma that manifest themselves in an eating disorder, one fails to target the source of the problem or even the core cause. If a person is obese but used to be anorexic or bulimic, then the solution to overeating is not to go on a diet. That might trigger a relapse into the other extreme, of undereating. This shows the importance of understanding the whole causal story of complex conditions, of which obesity is just one example. But these causes cannot be identified without taking the narrative of each single patient as an essential part of the available causal evidence.

5 Using Patient Narratives

Patient narratives can be different things and we will here mention three examples. They are all from the clinical encounter but represent slightly different approaches (see also Solomon 2015).

5.1 Narrative as a Tool for Causality Assessment

When a new drug is introduced on the market, it must be monitored for risk and safety purposes. In this process, patient narratives about possible side effects of medications are collected systematically and used as the basis for causality assessment and hypothesis generation. Some of these narratives come from the patients directly and into global databases such as VigiBase. Other narratives come from clinicians or from pharmacists, but in those cases, the narrative is interpreted and reported by someone other than the patient. Behind every case report, there is a patient narrative that is typically richer in detail and more personal than what is reported. If one is interested in causal complexity, individual variation and medical uniqueness, the patient narrative should be a better source of information than the case report, if the narrative contains more biographical, personal and contextual information. Rebecca Chandler, medical doctor at the Uppsala Monitoring Centre, writes:

Professionals working in drug safety also need patient stories. At its very essence, an individual case safety report is a patient story of an adverse experience after using a medicine. Often in pharmacovigilance we focus on numbers and statistics. We discuss Information Component values, proportional reporting ratios, completeness and VigiRank scores. Signal detection using spontaneously reported adverse event data is a hypothesis-generating exercise, a clinical science which is based upon individual reports of suspicions of causality between a medicinal product and an adverse event.

It is logical therefore that clinical stories contained in adverse event reports, complete with details and context, are integral to the development of hypotheses of drug safety concerns. Certain details within the patient story are integral to the building of hypotheses of causality, such as past medical history, concomitant medications, time to onset of symptoms. Other details, if provided, allow us to understand the impact of the event upon the patient’s life, their ability – or inability – to manage the adverse event, and even how the patient was treated within the healthcare system.

Pharmacovigilance is more than the identification of causal associations between drugs and new adverse events. It is about creating a culture of awareness of drug safety, and using patient stories to contribute to an evidence base that can be used by physicians and patients to make wise therapeutic decisions. (Chandler 2017: 23)

5.2 Narrative as a Tool for Understanding the Causal Story

Many clinicians who are interested in patient narratives are motivated by a philosophical commitment to phenomenology. Ontologically, phenomenology is a version of holism or wholism, and there are a number of overlapping ideas with dispositionalism. Phenomenology has been emphasised and practiced as a methodology by many of the CauseHealth clinicians, including Stephen Tyreman, Anna Luise Kirkengen (Chap. 15, this book), Brian Broom (Chap. 14, this book) and Karin Mohn Engebretsen (Chap. 11, this book). Depending on the version of phenomenology, the narrative should come solely or primarily from the patient, and it should remain as uninterpreted as possible by the clinician. As a clinical methodology, phenomenology emphasises the subjective experiences of health and illness, and also meaning, interpretation, values, existential questions and embodiment. In the case of chronic medically unexplained conditions, phenomenological approaches will have a broader focus suited for uncovering complexity and uniqueness. One example is presented by general practitioner Anna Luise Kirkengen:

For many years, Katherine Kaplan had been in specialist care due to a long sequence of diseases deemed as separate, different in origin and, consequently, requesting different types of approach. She had been frequently hospitalised with a variety of serious health problems since her late teens. She had encountered physicians in many medical specialties due to what was diagnosed as different diseases in various organ systems. She had been delayed in her studies due to these frequent periods of sickness and was, when finally reaching her graduation, completely incapacitated by chronic states of bad health which could not be responded to with specific treatments any more. Years of medical investment on specialist level were terminated with a referral to a General Practitioner.

In order to understand this disabling process, an analysis of the prevailing concepts of the human body, of diseases, and of medical causality needs to be performed.

When contrasting the “case” depicted above with a biographical account grounded in the “story”, a different picture emerges. Katherine Kaplan, the third child of a highly educated and resourceful couple, had been maltreated by both her parents but mostly by her elder brother from early childhood through adolescence and while she was a student of medicine at a Norwegian university. Her parents, defining their abusive acts as deserved punishment, had never realised that their daughter suffered grave and frequent maltreatment by the hands of their son. The on-going threat, embodied as toxic stress in Katherine, increasingly compromised her health preserving systems to the point of breakdown by the time of her graduation.

Anna Luise Kirkengen, ‘What if…’, CauseHealth blog (https://causehealthblog.wordpress.com/2017/10/17)

5.3 Narrative as a Collaborative Tool in Healthcare

A third type of narrative is the collaborative or co-written story, developed in the dialogue between the patient and the clinician. Here the clinician takes a more active role in bringing out, analysing and emphasising different parts of the patient’s narrative. In this process, the narrative might change from the individual perspectives of the patient and of the clinician toward a commonly constructed narrative (Low 2017, see also Low, Chap. 8 and Price, Chap. 7, this book). For example, a patient might not think much of how an experience affected their condition, while the clinician might think it is highly relevant. The opposite might also happen. The clinician might not initially understand why the patient mentions something that seems tangential to the medical issue, but then discover from the conversation that this was crucial. In this case, the patient’s own narrative becomes re-written as a result of the clinical interaction. This can be an important therapeutic tool, but it is also a tool for uncovering the causal complexity of how the person became ill and what affects the condition in positive and negative ways. The physician then offers the patient some tools to analyse her own subjective experience.

So why is the notion of story in medicine so foreign to clinicians? Typically we (the clinicians) want the medical truth rather than the human truth (we need both). Medical truth is largely about science, measurement, labelling (diagnosis), and standard ways of treating. These perspectives give us enormous benefits. But in our narrow desire to essentialise, master, know medically, deploy, and instrumentalise, we frequently fail to get close to the patient’s unique and individual story, and thus we lose a crucial dimension of the person that may be helping make them sick and keep them sick. If we make it safe for patients to tell their stories, many will do so. We need both the medical perspectives and the stories.

Brian Broom, from the mindbody website: https://wholeperson.healthcare

6 To Sum Up…

This chapter offered a philosophical diagnosis of the challenges that medicine is facing, regarding medically unexplained symptoms and complex illnesses. We proposed that a crucial problem comes from applying a Humean regularity theory of causality, in which a cause is understood as something that always provokes the same effect under ideal conditions, to the clinical reality, where no ideal condition, or average patient, can ever be found. A dispositionalist understanding of causality proposes instead to start from the particular and unique situation of the single case in order to understand causality. The medical evidence, including causally relevant evidence, must then be generated from the single patient. This includes not only the patient’s medical data, but also the patient’s condition, narrative and perspective. This is fundamental in order to generate causal hypotheses about the complex situation and all the dispositions that influence the medical condition. Ultimately, evidence from the clinical encounter could assist the design of experiments both in the lab and in the clinics. When possible, one should also use insights from statistical population studies to make decisions about single patients. The best approach to causality, we argue, is to use a plurality of methodologies. We have also explained how, when starting from a dispositional theory of causality, heterogeneity, unexpected results and outlier cases actually represent an epistemological advantage, instead of an obstacle, for the causal enquiry.

References

Anjum RL, Mumford S (2018) Causation in science and the methods of scientific discovery. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Anjum RL, Copeland S, Rocca E (2018) Medical scientists and philosophers worldwide appeal to EBM to expand the notion of ‘evidence’. BMJ EBM 25:6–8

Berkwits M, Aronowitz R (1995) Different questions beg different methods. J Gen Intern Med 10:409–410

Castaneda D, Popov VB, Wander P et al (2019) Risk of suicide and self-harm is increased after bariatric surgery—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 29:322–333

Chandler R (2017) The patient behind the statistics. Uppsala Rep 77:23

Chew-Graham CA, Heyland S, Kingstone T et al (2017) Medically unexplained symptoms: continuing challenges for primary care. Br J Gen Pract 67:106–107

Copeland S (2017) Unexpected findings and promoting monocausal claims, a cautionary tale. J Eval Clin Pract 23:1055–1061

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S et al (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

de Boer WA, Tytgat GNJ (2000) Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. BMJ 320:31

Engebretsen KM (2018) Suffering without a medical diagnosis. A critical view on the biomedical attitudes towards persons suffering from burnout and the implications for medical care. J Eval Clin Pract 24:1150–1157

Engebretsen KM, Bjorbækmo WS (2019) Naked in the eyes of the public: a phenomenological study of the lived experience of suffering from burnout while waiting for recognition to be ill. J Eval Clin Pract. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13244

Eriksen TE, Kirkengen AL, Vetlesen AJ (2013a) The medically unexplained revisited. Med Health Care Philos 16:587–600

Eriksen TE, Kerry R, Lie SAN et al (2013b) At the borders of medical reasoning – aetiological and ontological challenges of medically unexplained symptoms. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 8:1747–1753

Go MF (2002) Natural history and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 16:3–15

Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B (eds) (1998) Narrative based medicine. Dialogue and discourse in clinical practice. BMJ Books, London

Hellhammer DH, Hellhammer J (2008) Stress: the brain-body connection. Karger, Basel

Hume D (1739) In: Selby-Bigge LA (ed) A treatise of human nature. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1888

Jeffrey JE, Foster NE (2012) A qualitative investigation of physical therapists’ experiences and feelings of managing patients with nonspecific low back pain. Phys Ther 92:266–278

Karmali S, Brar B, Shi X et al (2013) Weight recidivism post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg 23:1922

Lagerros YT, Brandt L, Hedberg J et al (2017) Suicide, self-harm, and depression after gastric bypass surgery: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Surg 265:235–243

Low M (2017) A novel clinical framework: the use of dispositions in clinical practice. A person centred approach. J Eval Clin Pract 23:1062–1070

Mumford S, Anjum RL (2011) Getting causes from powers. Oxford University press, Oxford

Neovius M, Bruze G, Jacobson P et al (2018) Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6:197–207

Rocca E (2017) Bridging the boundaries between scientists and clinicians. Mechanistic hypotheses and patient stories in risk assessment of drugs. J Eval Clin Pract 23:114–120

Rocca E, Anjum RL (2020a) Causal evidence and dispositions in medicine and public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061813

Rocca E, Anjum RL (2020b) Erice call for change: Utilising patient experiences to enhance the quality and safety of healthcare. Drug Saf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-00919-2

Solomon M (2015) Making medical knowledge. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Vogt H, Ulvestad E, Eriksen TE et al (2014) Getting personal: can systems medicine integrate scientific and humanistic conceptions of the patient? J Eval Clin Pract 20:942–952

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Anjum, R.L., Rocca, E. (2020). When a Cause Cannot Be Found. In: Anjum, R.L., Copeland, S., Rocca, E. (eds) Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-41238-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-41239-5

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)