Abstract

The present chapter reviews the recent studies of the group of regional and urban economics on the impact of the European Union regional policy on regional development. In particular, the focus of the research program is on the identification of the mechanisms through which the local territorial characteristics mediate the effect of public investments. Results show a strong relationship between the territorial capital of regions and the effectiveness of the EU regional policy. This evidence conveys relevant implications for policy makers. In particular, it suggests that regions should invest in those assets that are complementary to the ones which they already have, in order to build a balanced economic system.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The European Union (EU) allocates every year about one-third of its budget to regional policies, i.e., to actions aimed at promoting the development of places in various fields, from transport infrastructure to ICT, from firms’ competitiveness to social inclusion. The allocation of funds across regions, however, is not distributed equally. About 51% of the budget is allocated to less developed regions, i.e., those with a level of per capita gross domestic product (GDP) lower than 75% of the EU average. Remaining funds are invested in transition regions (per capita GDP between 75 and 90% of the EU average) and more developed regions (per capita GDP above 90% of the EU average).

This asymmetric allocation of funding mirrors the redistributive principle of the benefits from economic integration which, since its establishment, guides EU regional policy. In the words of Jacques Delors, “all regions of the Community ought to be able to share progressively in these benefits. (…) It is for this reason that the ‘transparency’ of the large market should be facilitated by supporting the efforts of regions with ill-adapted structures and those in the throes of painful restructuring. Community policies can be of assistance to these regions, which in no way absolves them from assuming their own responsibilities and from making their own effort” (Delors 1987, p. 7).

Therefore, the ultimate goal of regional policy is, through the promotion of socioeconomic development in regions less favored by European integration, to reinforce territorial cohesion within the EU. For this reason, the EU regional policy is often labeled as Cohesion Policy.

The assessment of Cohesion Policy is fundamental to understand whether this target has been achieved. A long stream of research has focused on this issue, with the aim of measuring the net impact of EU regional policy on the development of regions, mainly interpreted in terms of GDP and employment growth. Empirical evidence of a positive association between CP funding and economic prosperity, however, appeared to be inconsistent across studies (Dall’Erba and Le Gallo 2008; Becker et al. 2012), especially because there are empirical and conceptual issues which cannot yet be reconciled (Fratesi 2016): Whether Cohesion Policy had a positive effect on regional development or not, is still an open question in the literature.

The group of regional and urban economics formulated a hypothesis for explaining the divergence of empirical results from previous studies. According to this hypothesis, the way in which Communitarian policies are implemented and their effectiveness, can change substantially due to certain specific territorial assets characterizing EU regions. In other words, the territory and, more specifically, the territorial capital of regions, is not neutral in the mechanism through which policy implementation generates development. Instead, specific characteristics of regions mediate the impact of Cohesion Policy, and it is therefore necessary to keep them in mind in the policy assessment.

Stemming from this assumption, the aim of the research program of the group of regional and urban economics was to understand and measure the differentiated effects of EU regional policy across different territories. More precisely, the association between the territory and Cohesion Policy addressed three main issues:

-

territorial capital and the allocation of Cohesion Policy funds: As stated above, Cohesion Policy focuses on a variety of policy targets. It is therefore important to study the relationship between regional characteristics and the allocation of funding across different policy needs because it allows us to understand and improve the allocation mechanisms.

-

territorial capital and the effectiveness of Cohesion Policy: The effect of EU regional policy on regional development is assumed to be differentiated, according to the regional endowment of territorial capital.

-

territorial capital and the development of regions: Apart from the direct association between territorial capital and Cohesion Policy, it is relevant to fully understand the role of the territory on the development of regions, i.e., on the overall contexts in which policies are implemented.

The next section will discuss the conceptual and methodological approach adopted, with a clear explanation of what is meant by “territorial capital” and how it could be related to Cohesion Policy. The other sections will summarize the results of the study of the three issues defined above.

2 Territorial Capital and EU Regional Policy

The identification of the sources of endogenous local development is one of the main issues of regional economics. Human capital, physical infrastructures and social capital are all examples of single territorial assets having been proved to positively affect prosperity. A comprehensive and general approach to this topic, however, requires a coherent and exhaustive classification of all potential endogenous sources of development.

In this perspective, OECD (2001) firstly introduced the concept of territorial capital, defined as the system of territorial assets having economic, cultural, social and environmental nature. In order to succeed, regions and territories have to exploit the potential of this complex set of locally based factors. Camagni (2008) provided a taxonomy for these elements, based on the dimensions of materiality and rivalry. Instead of providing just a list of local assets, this approach explicitly defines their properties, allowing to identify potential interactions and policy implication.

The taxonomy is reported in Fig. 1, showing how territorial capital includes very different assets, from physical infrastructures (box a) to human capital (box f) to social capital (box d).

Source Camagni (2008)

Territorial capital: a taxonomy.

This classification of regional assets was chosen to study the relationship between regional characteristics and the implementation of Cohesion Policy. The idea that the local context of implementation mediates the effects of EU regional policy is not new in literature. In fact, some studies tested, for example, whether policy effectiveness is higher in more developed regions (Cappelen et al. 2003) or in areas with high-quality institutions (Rodríguez-Pose and Garcilazo 2015). The innovative aspect of the approach of the research group, however, relies on its ability to consider, at the same time, the whole set of territorial characteristics, and therefore their joint effect on the outcome of Cohesion Policy.

3 Territorial Capital and the Allocation of Cohesion Policy Funds

A further element of complexity in the identification of an empirical association between territorial capital and the effectiveness of Cohesion Policy relies on the fact that regions may differ not just in terms of their territorial characteristics but, also, in the mix of policies they decide to implement (Rodríguez-Pose and Fratesi 2004). Regions are likely to adopt different growth strategies, investing the Cohesion Policy funds received in those territorial assets which they hope will maximize the local growth potential.

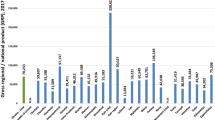

In order to shed light on this issue, this first step of the analysis (Fratesi and Perucca 2016) collected, at a fine territorial scale (NUTS3),Footnote 1 statistical data on territorial capital endowment (Perucca 2013). This data covered the categories of assets is reported in Fig. 1. Matching this data with evidence on the Cohesion Policy expenditure on 19 axesFootnote 2 over the Programming Period 2000–2006,Footnote 3 the goal of the analysis was (i) to classify EU regions according to their territorial capital and (ii) associate this endowment with the allocation of funds across different axes of expenditure.

Empirical results (Fratesi and Perucca 2016) highlight that regions with different endowments of territorial capital allocate their funds in a different way. Core metropolitan areas, characterized by the highest levels of territorial capital, allocate, on average, 26.9% of their funds to the support of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and the craft sector, i.e., to investments aimed at increasing the competitiveness of their firms. At the same time, these regions are those allocating more resources in actions on human capital, from the labor market to social inclusion. On the other hand, regions characterized by the lowest endowments of territorial capital are also those devoting more resources to investments in basic infrastructure such as transport, energy and environmental infrastructure.

Summing up, less developed regions tend to invest relatively more in basic infrastructural assets, i.e., in those resources that are still lacking in the region. Richer areas, already endowed with infrastructures, tend to pay more attention to social and economic issues. Even if different typologies of regions tend to allocate their funds differently across axes of expenditure, it is not possible to say whether this choice is the most efficient. In other words, we do not know whether the allocation strategy is associated with a higher impact on investments. This issue is the focus of the second step of the analysis, discussed in the following sections.

4 Territorial Capital and the Effectiveness of Cohesion Policy Funds

The assumption on the association between territorial capital and Cohesion Policy is that specific territorial characteristics foster the effectiveness of the EU regional policy. The empirical verification of this assumption requires, in the first place, the definition of what is meant by the term effectiveness. In our approach, the outcome of Cohesion Policy is defined in terms of increased GDP growth: the higher the statistical impact on economic growth in the years after the policy implementation, the higher the effects of Cohesion Policy.Footnote 4 This choice is based on the fact that EU regional policy is aimed, in the first place, at reducing economic disparities within the EU, by increasing income in lagging-behind regions.

The methodological approach was similar to the one described in Sect. 2. Territorial capital for all EU NUTS3 regions was measured, jointly with data on Cohesion Policy funding across different axes of expenditure. Then, an empirical model was estimated, where GDP growth in the years after the end of the Programming Period 2000–2006 is assumed to be a function, among other characteristics, of the territorial capital of regions, the funds they received and the interactions between the two elements. This analysis allowed us to check whether Cohesion Policy investments had an impact on regional economic growth and if this impact was differentiated for regions with different endowments of territorial capital. Given the structural differences between eastern and western EU countries, the analysis was carried out separately for the two groups of nations.

In eastern EU countries (Fratesi and Perucca 2014), policy investments in immaterial assets (boxes d, e and f in Fig. 1) are characterized by increasing returns, i.e., they tend to be more effective where regions are more endowed. For instance, labor market policies are only effective when in the region there is a presence of high-value functions. Similarly, policies on workforce flexibility, entrepreneurship, innovation and ICT are only effective when the regions are endowed with human capital.

On the other hand, the effect of investments in tangible assets (boxes a, b and c in Fig. 1) is mediated mainly by regions’ level of urbanization and agglomeration economies. In this case, decreasing returns emerge, since intermediate urban areas (and neither metropolitan nor rural areas) gain from those where Cohesion Policy is most effective. In general, the fact that Cohesion Policy is more effective in correspondence to higher endowments of territorial capital, implies that investing policy funds in regions that already more developed can pay more than investing them in weaker regions. This suggests the existence of a potential trade-off between the effectiveness of policies and the achievement of territorial cohesion.

Evidence from western EU countries (Fratesi and Perucca 2019), where data depth allows a more systemic analysis, suggests different and more complex mechanisms compared with those presented above. First of all, the idea that policies tend to have larger effects where territorial capital assets are present remains because many policies have higher impacts in regions which are rich in territorial capital, while some decreasing returns also exist in areas such as R&D and telecommunication infrastructure.

Even more interesting is the observation that policies which invest in assets which are complementary to those already present in regions. For example, areas characterized by high levels of collective goods, human capital and behavior exhibit lower returns than other clusters in fields making intense use of assets of this kind. Finally, areas which are very poorly endowed with territorial capital tend to have lower returns in all assets but those, such as SMEs, directly related to the private firm establishment, most likely because firms in areas lacking territorial capital are more in need of assistance than firms elsewhere.

The way in which support to firms interacts with territorial capital has been further investigated in Bachtrögler et al. (2019), thanks to collaboration with the Vienna University of Economics and Business and the WIFO. In this case, the analysis was developed thanks to a database of firms put together by our partner for many European countries for the Programming Period 2007–13.

An EU-wide analysis based on propensity score matching shows that the impact of Cohesion Policy support to firms is highly impactful on the firms’ size (in terms of GVA and employment), yet, while the impact on productivity is still significant, it turns out to be much smaller. Going down to the individual countries, the analysis shows important differences, in terms of magnitude and significance of the effects.

Finally, the analysis goes down to the regional NUTS2 level, showing that the impacts of firm support are differentiated within countries as well and in different ways in the different countries. It seems that, for some countries, the impact of firm support depends on needs, i.e., is higher where regions lack complementary assets.

5 Territorial Capital and Regional Development

The framework of territorial capital can also be fruitfully applied to the explanation of growth tout court. Following ten years of crisis with sluggish recovery, the research group addressed the issue of resilience, which is an engineering concept which has now been widely adopted in economics to show the capability of economies to react to crises.

Different measures of resilience exist on a regional level, and these were analyzed by Fratesi and Perucca (2018) in view of dependence on the territorial capital endowment of regions.

The analysis shows, first, that regions with different endowments of territorial capital are differently resilient in quantitative terms because those with more territorial capital are also more resilient and, second, that the typologies of territorial capital are relevant, because depending on the presence of one or the other, they are also resilient in different ways (e.g., in terms of resistance or recovery). In particular, different territorial capital assets have different effects, and those more closely linked to resilience measures are those that have an intermediate level of materiality and/or rivalry (see Fig. 1). The second result is the confirmation of the expectation that less mobile factors of both a private and public nature are more linked to resilience, being difficult to transfer from one region to the other.

The paper hence concludes that the structure of regions is an important determinant of how they can afford periods of distress.

6 Conclusions and Future Research Directions

The research program on territorial capital and regional policies has already offered many hints which will be helpful to policy makers, for example, the fact that regions should invest in those assets that are complementary to the ones which they already have, in order to build a balanced economic system.

At the same time, the research already accomplished paves the way for further research, along with a number of directions.

The first direction is the systematic study of the determinants of regional policy effectiveness under different conditions, in order to provide policy makers with a matrix of which policy interventions are helpful in each situation.

The second direction is the microeconomic study of the micro-territorial determinants of regional policy effectiveness. The presence of other firms nearby, with complementary or synergic possibilities, and the presence of territorial assets are expected to play a role which takes place on a scale which is smaller than the regional one. Although the theory is aware of the fact that regions are far from homogenous internally, they are often treated as such in the econometric analyses, where each of them is a single observation.

Finally, the research program has demonstrated the fruitfulness of the territorial capital concept, which was developed within the research group, for the analysis of regional growth and regional policy. Our conceptual understanding of the link between local territorial assets, policies and other assets in neighboring regions can still be deepened with the study of the actual mechanisms by which the effects take place.

Notes

- 1.

The NUTS (nomenclature of territorial units for statistics) classification is the official classification adopted in the EU for the administrative sub-national regions.

- 2.

An axis of expenditure is the thematic field in which the policy intervenes. Tourism, ICT, transport, energy and environment, female labor participation are all examples of aces of expenditure. See Fratesi and Perucca (2016) for the full list.

- 3.

The Multiannual Financial Frameworks set the annual budgets for seven-year periods. A Programming Period is, as a consequence, a seven-year period characterized by a given budget and rules for Cohesion Policy.

- 4.

This relationship has to be controlled for all the other factors, apart from Cohesion Policy investments, that may affect GDP growth. See Fratesi and Perucca (2014) for a detailed description of the methods and of how this issue was addressed in the empirical analysis.

References

Bachtrögler, J., Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2019). The influence of the local context on the implementation and impact of EU Cohesion Policy. Regional Studies, forthcoming and on-line. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1551615.

Becker, S. O., Egger, P. H., & Von Ehrlich, M. (2012). Too much of a good thing? On the growth effects of the EU’s regional policy. European Economic Review, 56(4), 648–668.

Camagni, R. (2008). Regional Competitiveness: Towards a Concept of territorial capital. In R. Capello, R. Camagni, B. Chizzolini, & U. Fratesi (Eds.), Modelling regional scenarios for the enlarged Europe: European competitiveness and global strategies, (pp. 33–48). Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Cappelen, A., Castellacci, F., Fagerberg, J., & Verspagen, B. (2003). The impact of EU regional support on growth and convergence in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 41(4), 621–644.

Dall’Erba, S., & Le Gallo, J. (2008). Regional convergence and the impact of European structural funds 1989-1999: A spatial econometric analysis. Papers in Regional Science, 87(2), 219–244.

Delors, J. (1987). The Single Act: A New Frontier for Europe. Communication from the Commission to the Council. COM (87) 100 final, 15 February 1987. Bulletin of the European Communities, Supplement 1/87.

Fratesi, U. (2016). Impact assessment of European cohesion policy: Theoretical and empirical issues. In S. Piattoni & L. Polverari (Eds.), Handbook on cohesion policy in the EU (pp. 443–460). Chelthenham: Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1-78471-566-3.

Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2014). Territorial capital and the effectiveness of cohesion policies: An assessment for CEE regions. Investigaciones Regionales, 29, 165–191.

Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2016). Territorial capital and EU Cohesion Policy. EU Cohesion Policy. In: J. Bachtler, P. Berkowitz, S. Hardy, & T. Muravska, (Eds.), EU cohesion policy (open access): Reassessing performance and direction. Taylor & Francis.

Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2018). Territorial capital and the resilience of European regions. The Annals of Regional Science, 60(2), 241–264.

Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2019). EU regional development policy and territorial capital: A systemic approach. Papers in Regional Science, 98(1), 265–281.

OECD (2001): OECD Territorial Outlook, Paris.

Perucca, G. (2013). A redefinition of Italian macro-areas: The role of territorial capital. Rivista di Economia e Statistica del Territorio, 2, 37–65.

Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Fratesi, U. (2004). Between development and social policies: the impact of European Structural Funds in Objective 1 regions. Regional Studies, 38(1), 97–113.

Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Garcilazo, E. (2015). Quality of government and the returns of investment: Examining the impact of cohesion expenditure in European regions. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1274–1290.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fratesi, U., Perucca, G. (2020). EU Regional Policy Effectiveness and the Role of Territorial Capital. In: Della Torre, S., Cattaneo, S., Lenzi, C., Zanelli, A. (eds) Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective. Research for Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33256-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33256-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-33255-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-33256-3

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)