Abstract

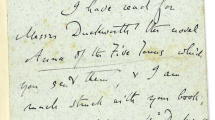

Jane Austen’s letters contain few insights into her practice or philosophy as a writer. A series of letters in 1814 to her niece Anna offer comments and advice on the ongoing novel which this budding author has sent her aunt for feedback, but these are mainly of a practical nature, concerning such matters as names, titles and etiquette (‘And when Mr Portman is first brought in, he wd not be introduced as the Honble—That distinction is never mentioned at such times;—at least I beleive not’). The majority of the letters which survive are concerned with day-to-day, rather than literary or intellectual, concerns. Jane’s letters to her sister Cassandra in particular are full of commonplace gossip between sisters, which could strike a modern reader as trivial, even frivolous. Their structure and style are, as many critics have noticed, akin to the spontaneity and rapidity of speech. In the novels such breathless letters are frequently a sign of negligent behaviour, even moral weakness. However, the letter can be a much more complex form in Austen’s fiction. Letters in her novels do not always reveal character so transparently, and the focus is often on difficulties surrounding their interpretation. The deciphering of epistolary meaning involves Austen’s heroines in some of their deepest personal struggles, and as a result these scenes of reading are crucial in each novel. Far from being trivial and frivolous, the letter is for Austen a powerful means of illustrating fictional consciousness, and the key to generating sophisticated stylistic techniques.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Jane Austen’s Letters, ed. Deidre Le Faye, 4th ed. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 280. Hereafter JAL.

- 2.

Unfortunately the other half of the conversation has been lost; no letters from Cassandra to Jane survive, and according to family tradition Cassandra burned the majority of Jane’s letters to her two or three years before her own death in 1845 (see JAL, pp. xii–xiii).

- 3.

Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade, In Search of Jane Austen: The Language of the Letters (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 6.

- 4.

Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility, ed. Edward Copeland ([1811]; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 40. Hereafter SS.

- 5.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, ed. Pat Rogers ([1813]; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 321. Hereafter PP.

- 6.

Ian Jack, “The Epistolary Element in Jane Austen,” English Studies Today, 2nd series (1961), pp. 173–86 (185).

- 7.

Ralph Tumbleson, “‘It is Like a Woman’s Writing’: The alternative epistolary novel in Emma,” Persuasions 14 (1992), pp. 141–43, 141.

- 8.

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey, ed. Barbara M. Benedict and Deidre Le Faye ([1818]; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 223–24. Herefter NA.

- 9.

Jack, p. 173.

- 10.

There is not space enough here to detail Austen’s early experiments with epistolary form. The juvenilia contains several playful mini novels-in-letters, while Lady Susan, probably written around 1794–95, is a sophisticated, dazzling demonstration of the conflicting points of view which the epistolary novel can generate.

- 11.

Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, ed. John Wiltshire ([1814]; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 434. Hereafter MP.

- 12.

For more on free indirect thought, usually seen by critics as Austen’s most lasting contribution to the style of the English novel, see Joe Bray, The Language of Jane Austen (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), chapter 4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bray, J. (2020). The Tensions of Jane Austen’s Epistolary Style. In: Callaghan, M., Howe, A. (eds) Romanticism and the Letter. Palgrave Studies in the Enlightenment, Romanticism and Cultures of Print. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29310-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29310-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-29309-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-29310-9

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)