Abstract

Interactions between knowledge and health are studied in a three-period overlapping generations model with health persistence. Agents face a non-zero probability of death in adulthood. In addition to working, adults allocate time to child rearing. Growth dynamics depend in important ways on the externalities associated with knowledge and health. Depending on the strength of these externalities, increases in government spending on education or health (financed by a cut in unproductive spending) may have ambiguous effects on growth. Trade-offs between education and health spending can be internalized by solving for the growth-maximizing expenditure allocation. With an endogenous adult survival rate, multiple growth paths may emerge. A reallocation of public spending from education to health may shift the economy from a low-growth equilibrium to a high-growth equilibrium.

I am grateful to Barış Alpaslan and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on a preliminary draft. However, I bear sole responsibility for the views expressed here. The technical appendix is available upon request.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Two comprehensive composite measures of human capital have been published recently. The first, by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, covers 195 countries, whereas the second, by the World Bank, covers 157 countries. See https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31941-X/fulltext and http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2019.

- 2.

Among available studies, Baldacci et al. (2004), using cross-country regressions, found that health outcomes (as proxied by the under-five child mortality rate) have a statistically significant effect on school enrollment rates.

- 3.

- 4.

See for instance the results of Powdthavee and Vignoles (2008) for Britain.

- 5.

Tang and Zhang (2007) develop an OLG model with education and health but do not account for direct interactions between them. Tamura (2006) and Ricci and Zachariadis (2013) develop OLG models where schooling exerts external effects on health, in the form of a negative effect on adult mortality in the first case and a positive effect on longevity in the second. In the models of Galor and Mayer-Foulkes (2004) and Hazan and Zoabi (2006), health is, in addition to education, an input in the production of human capital. However, none of these contributions fully examines bidirectional effects, and the role of public policy, as is done here. Finally, Agénor (2011) do account for bidirectional effects in a continuous time, infinite-horizon setting, but in their model health is not stationary.

- 6.

- 7.

The assumption that the survival rate is constant initially is for expositional reasons. It helps to clarify the role of externalities and the fundamental trade-off between spending on education and spending on health.

- 8.

- 9.

See Bleakley (2010b) for an overview of the evidence on the impact of health and education.

- 10.

Research at the National institute of Health in the United States has also shown that the children of mothers who did not eat food with ample omega-3 fatty acids had a lower IQ than children who did.

- 11.

- 12.

At the same time, child development may also be related to a child’s socioeconomic background (see Taylor et al., 2004). If so then children from disadvantaged families may fall behind early in life and may be unable to catch up later.

- 13.

See also Oreopoulos et al. (2008), who found in a study for Canada that poor infant health is a strong predictor of future education outcomes.

- 14.

- 15.

As noted by Kohler and Soldo (2004) for instance, it is useful to separate two potential channels that may relate parents’ education to their children’s health and offsprings’ late life health outcomes. The first is the father’s education, which likely operates through economic circumstances (because fathers may be those who were the primary suppliers of economic resources in the family). The second is the mother’s education, which operates through knowledge about health care and health behavior that are essential determinants of children’s health outcomes.

- 16.

- 17.

The gender dimension of the interactions between education and health is further discussed in the concluding remarks.

- 18.

For simplicity, the direct cost of schooling and the cost of keeping children healthy (medicines, and so on) are abstracted from.

- 19.

If parents care equally about the health and education of their child, η E = η H.

- 20.

Alternatively, it could be assumed that the saving left by individuals who do not survive to old age is confiscated by the government, which transfers them in lump-sum fashion to surviving members of the same cohort. The effective rate of return to saving would thus be (1 + r t+1)∕p, which would yield an equation similar to (8.4). See Agénor (2012, Chapter 3) for a simple derivation.

- 21.

A more general specification would be to set \(A_{t}=E_{t}^{\chi }h_{t}^{1-\chi }\), where χ ∈ (0, 1).

- 22.

This assumption is consistent with the evidence for Sub-Saharan Africa for instance, which suggests that only 6.8 percent of youth engage in tertiary education, compared to a world average of 30 percent (United Nations, 2016, p. 46).

- 23.

See Osang and Sarkar (2008) and Agénor (2015). Of course, a similar argument could apply for the production of education services in (8.11). However, unlike health, knowledge does grow without bounds and the specification adopted in that equation is sufficient to ensure constant growth in the steady state.

- 24.

Activity in that case could of course be measured by the level of final output, but given the linear relationship between Y t and K t implied by (8.10) the use of the latter is mainly a matter of convenience.

- 25.

- 26.

Using θ 1 = 0.55, as in Osang and Sarkar (2008, Table 4) for instance, and a standard value of β = 0.65, this condition implies that θ 4 cannot be higher than 0.64.

- 27.

Note that Case 2 is qualitatively very similar to Case 1. An exhaustive analysis of all cases would require a numerical calibration.

- 28.

There are also intermediate cases, where one type of externality is high and the other low, which are ignored for the moment to facilitate the exposition of the graphical analysis.

- 29.

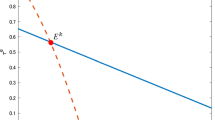

Curve HH can be either concave or convex, depending on whether \([1-(\beta \theta _{1}+\theta _{4})]/(\beta \theta _{1}+\theta _{3})\gtrless 1\). For illustrative purposes, it is shown as concave in Fig. 8.1. The difference between Cases 1 and 4, of course, is that the slopes of the two curves would be different, depending on the values of ν 3 and θ 3. However, this difference is inconsequential for a qualitative analysis.

- 30.

Note that if ϕ 2 = β then a 12 = 0 and system (8.24) is recursive; the dynamics are in terms of \(\hat {x}_{t}\) only. Then stability requires a 11 = 1 − β + ϕ 1 < 1, or ϕ 1 < β. If ν 3 = 0, then this condition becomes β(ν 1 − 1) < 1 which is always satisfied.

- 31.

A variety of other experiments could also be conducted, such as for instance a change in parental time allocated between the health and education needs of their children, that is, a change in χ. These experiments are left to the interested reader.

- 32.

The focus on growth could be because the economy considered is poor and the priority is to raise living standards. More formally, differences between the growth- and welfare-maximizing solutions can lead to relatively small differences in growth rates, and possibly welfare levels. See Misch et al. (2013) for a discussion.

- 33.

Some other contributions which focus on knowledge accumulation, such as Blackburn and Cipriani (2002), Cervellati and Sunde (2005), Castelló-Climent and Doménech (2008), for instance, have assumed that life expectancy is related to education. This can be justified by arguing that, as noted earlier, improved knowledge can lead to changes in lifestyle that may translate into better health outcomes. In the present setting, a more general approach, of course, would be to consider jointly education and health status as determinants of life expectancy. However, this would complicate significantly the analysis and would detract from the main contribution of this chapter.

- 34.

A simple functional form for f could be the exponential function, that is, \(p_{t}=1-1/\exp (h_{t})\).

- 35.

As noted in Agénor (2015), in the model health status can be interpreted as a broad measure of health, such as the body mass index (BMI). From that perspective, the thresholds h L and h H can be thought of as the lower and upper bounds of the BMI Chart, which are commonly used to measure the ranges for underweight (up to h L in the model), healthy weight (between h L and h H), and overweightandobesity (above h H), based on a person’s height. The last threshold is, in practice, further decomposed into separate thresholds for overweight and obesity but this does not matter from the perspective of this discussion.

- 36.

Based on the previous discussion, if the increase in public spending on health is financed by a cut in spending on education, the possibility of an adverse effect on growth would be magnified.

- 37.

Hazan and Zoabi (2006), however, focus on private expenditure on health and education, not public spending.

References

Agénor, Pierre-Richard, “Schooling and Public Capital in a Model of Endogenous Growth,” Economica, 78 (January 2011), 108–32.

——, Public Capital, Growth and Welfare, Princeton University Press (Princeton, New Jersey: 2012).

——, “Public Capital, Health Persistence and Poverty Traps,” Journal of Economics, 115 (June 2015), 103–31.

Agénor, Pierre-Richard, Otaviano Canuto, and Luiz Pereira da Silva, “On Gender and Growth: The Role of Intergenerational Health Externalities and Women’s Occupational Constraints,” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 30 (September 2014), 132–47.

Ahmed, Akhter, and Mary Arends-Kuenning, “Do Crowded Classrooms Crowd Out Learning? Evidence from the Food for Education Program in Bangladesh,” World Development, 34 (April 2006), 665–84.

Altindag, Duha, Colin Cannonier, and Naci Mocan, “The Impact of Education on Health Knowledge,” Economics of Education Review, 30 (November 2011), 792–812.

Ampaabeng, Samuel K., and Chih Ming Tan, “The Long-Term Cognitive Consequences of Early Childhood Malnutrition: The Case of Famine in Ghana,” Journal of Health Economics, 32 (December 2013), 1013–27.

Arndt, Channing, “HIV/AIDS, Human Capital, and Economic Growth Prospects for Mozambique,” Journal of Policy Modeling, 28 (July 2006), 477–489.

Aslam, Monazza, and Geeta G. Kingdon, “Parental Education and Child Health—Under- standing the Pathways of Impact in Pakistan,” World Development, 40 (October 2012), 2014–32.

Baldacci, Emanuele, Benedict Clements, Sanjeev Gupta, and Qiang Cui, “Social Spending, Human Capital, and Growth in Developing Countries: Implications for Achieving the MDGs,” Working Paper No. 04/217, International Monetary Fund (November 2004).

Behrman, Jere R., “The Impact of Health and Nutrition on Education,” World Bank Research Observer, 11 (February 1996), 23–37.

——, “Early Life Nutrition and Subsequent Education, Health, Wage, and Intergenerational Effects,” in Health and Growth, ed. by Michael Spence and Maureen Lewis, World Bank (Washington, D.C.: 2009).

Bell, Clive, Shantayanan Devarajan, and Hans Gersbach, “The Long-Run Economic Costs of AIDS: A Model with an Application to South Africa,” World Bank Economic Review, 20 (March 2006), 55–89.

Benos, Nikos, and Stefania Zotou, “Education and Economic Growth: A Meta-Regression Analysis,” World Development, 64 (December 2014), 669–89.

Bharadwaj, Prashant, Katrine V. Løken, and Christopher Neilson, “Early Life Health Interventions and Academic Achievement,” American Economic Review, 103 (August 2013), 1862–91.

Blackburn. Keith, and Giam P. Cipriani, “A Model of Longevity and Growth,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control,” 26 (February 2002), 187–204.

Bleakley, Hoyt, “Disease and Development: Evidence from Hookworm Eradication in the American South,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122 (February 2007), 73–117.

——, “Malaria Eradication in the Americas: A Retrospective Analysis of Childhood Exposure,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2 (April 2010a), 1–45.

——, “Health, Human Capital, and Development,” Annual Review of Economics, 2 (September 2010b), 283–310.

Bloom, David E., David Canning, and Mark Weston, “The Value of Vaccination,” World Economics, 6 (July 2005), 1–13.

Bloom, David, and David Canning, “Schooling, Health, and Economic Growth: Reconciling the Micro and Macro Evidence,” unpublished, Harvard School of Public Health (February 2005).

Bloom, David E., and David Canning, “Population Health and Economic Growth,” in Health and Growth, ed. by Michael Spence and Maureen Lewis, World Bank (Washington DC: 2009).

Breierova, Lucia, and Esther Duflo, “The Impact of Education on Fertility and Child Mortality: Do Fathers really Matter less than Mothers?” Working Paper No. 10513, National Bureau of Economic Research (May 2004).

Bundy, Donald, et al., “School-Based Health and Nutrition Programs,” in Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, ed. by Dean Jamison et al., 2nd ed., Oxford University Press (New York: 2006).

Case, Anne, Angela Fertig, and Christina Paxson, “The Lasting Impact of Childhood Health and Circumstance,” Journal of Health Economics, 24 (March 2005), 365–89.

Castelló-Climent, Amparo, and Rafael Doménech, “Human Capital Inequality, Life Expectancy and Economic Growth,” Economic Journal, 118 (April 2008), 653–77.

Cervellati, Matteo, and Uwe Sunde, “Human Capital, Life Expectancy, and the Process of Economic Development,” American Economic Review, 95 (December 2005), 1653–72.

Chou, Shin-Yi, Jin-Tan Liu, Michael Grossman, and Ted Joyce, “Parental Education and Child Health: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Taiwan,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2 (January 2010), 33–61.

Corrigan, Paul, Gerhard Glomm, and Fabio Mendez, “AIDS Crisis and Growth,” Journal of Development Economics, 77 (June 2005), 107–24.

Currie, Janet “Child Health in Developed Countries,” in Handbook of Health Economics, Vol. 1B, ed. by A. Culyer and J. Newhouse, North Holland (Amsterdam: 2000).

——, “Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Socioeconomic Status, Poor Health in Childhood, and Human Capital Development,” Journal of Economic Literature, 47 (March 2009) 87–122.

Cutler, David M., Angus Deaton, and Adriana Lleras-Muney, “The Determinants of Mortality,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20 (June 2006), 97–120.

Cutler, David M., and Adriana Lleras-Muney, “Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence,” in Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy, ed. by J. House, R. Schoeni, G. Kaplan, and H. Pollack, Russell Sage Foundation (New York: 2008).

de la Croix, David, and Omar Licandro, “The Child is Father of the Man: Implications for the Demographic Transition,” 123 (March 2013), 236–61.

Field, Erica, Omar Robles, and Maximo Torero, “Iodine Deficiency and Schooling Attainment in Tanzania,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1 (March 2009), 140–69.

Finlay, Jocelyn, “Endogenous Longevity and Economic Growth,” unpublished, Australian National University (February 2006).

——, “The Role of Health in Economic Development,” PGDA Working Paper No. 21, Harvard School of Public Health (March 2007).

Galor, Oded, and David Mayer-Foulkes, “Food for Thought: Basic Needs and Persistent Educational Inequality,” unpublished, Brown University (June 2004).

Gertler, Paul, and Jenifer Zeitlin, “The Returns to Childhood Investments in terms of Health later in Life,” in Health and Health Care in Asia, ed. by Teh-Wei Hu and H- Cheen, Oxford University Press (Oxford: 1996).

——, “Do Childhood Investments in Education and Nutrition Improve Adult Health in Indonesia?,” in The Economics of Health care in Asia-Pacific Countries, ed. by Teh-Wei Hu, E. Elgar (Cheltenham: 2002).

Glewwe, Paul, “Why Does Mother’s Schooling Raise Child Health in Developing Countries? Evidence from Morocco,” Journal of Human Resources, 34 (March 1999), 124–59.

——, “Schools and Skills in Developing Countries: Education Policies and Socioeconomic Outcomes,” Journal of Economic Literature, 40 (June 2002), 436–82.

Glewwe, Paul, and Edward Miguel, “The Impact of Child Health and Nutrition on Education in Less Developed Countries,” in Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 4, ed. by T. Paul Schultz and John Strauss, North Holland (Amsterdam: 2008).

Grossman, Michael, and R. Kaestner, “Effects of Education on Health,” in The Social Benefits of Education, ed. by Jere R. Berhman and Nevzer Stacey, University of Michigan Press (Ann Arbor: 1997).

Grossman, Michael, “The Relationship between Health and Schooling,” Nordic Journal of Health Economics, 3 (March 2015), 7–17.

Groot, Wim, and Henriette M. van den Brink, “The Effects of Education on Health,” in Human Capital: Advances in Theory and Evidence, ed. by Joop Hartog and Henriette M. van den Brink, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge: 2007).

Guryan, Jonathan, Erik Hurst, and Melissa Kearney, “Parental Education and Parental Time with Children,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22 (June 2008), 23–46.

Hamoudi, Amar, and Nancy Birdsall, “HIV/AIDS and the Accumulation and Utilization of Human Capital in Africa,” in The Macroeconomics of HIV/AIDS, ed. by M. Haacker, International Monetary Fund (Washington, D.C.: 2004).

Hazan, Moshe, and Hosny Zoabi, “Does Longevity Cause Growth? A Theoretical Critique,” Journal of Economic Growth, 11 (December 2006), 363–76.

Jayachandran, Seema, and Adriana Lleras-Muney, “ Life Expectancy and Human Capital Investments: Evidence from Maternal Mortality Declines,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124 (February 2009), 349–97.

Keats, Anthony, “Women’s Schooling, Fertility, and Child Health Outcomes: Evidence from Uganda’s Free Primary Education Program,” Journal of Development Economics, 135 (November 2018), 142–59.

Kohler, Iliana, and Beth J. Soldo, “Early Life Events and Health Outcomes in Late Life in Developing Countries—Evidence from the Mexican Health and Aging Study,” unpublished, University of Pennsylvania (March 2004).

Lorentzen, Peter, John McMillan, and Romain Wacziarg, “Death and Development,” Journal of Economic Growth , 13 (June 2008), 81–124.

Maluccio, John A., John Hoddinott, Jere R. Behrman, Reynaldo Martorell, Agnes R. Quisumbing, Aryeh D. Stein, “The Impact of Improving Nutrition during Early Childhood on Education among Guatemalan Adults,” Economic Journal, 119 (April 2009), 734–63.

Mayer-Foulkes, David, “Human Development Traps and Economic Growth,” in Health and Economic Growth: Findings and Policy Implications, ed. by Guillem López-Casasnovas, Berta Rivera and Luis Currais, MIT Press (Boston, Mass.: 2005).

McCarthy, Desmond, Holger Wolf, and Yi Wu, “The Growth Costs of Malaria,” Working Paper No. 7541, National Bureau of Economic Research (February 2000).

McGuire, James W., “Basic Health Care Provision and Under-5 Mortality: A Cross-National Study of Developing Countries,” World Development (March 2006), 405–25.

Mental Health Foundation, Feeding Minds—The Impact of Food on Mental Health, London (January 2006).

Miguel, Edward, “Health, Education, and Economic Development,” in Health and Economic Growth: Findings and Policy Implications, ed. by Guillem López-Casasnovas, Berta Rivera, and Luis Currais, MIT Press (Cambridge, Mass.: 2005).

Miguel, Edward, and Michael Kremer, “Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities,” Econometrica, 72 (January 2004), 159–217.

Misch, Florian, Norman Gemmell, and Richard Kneller, “Growth and Welfare Maximization in Models of Public Finance and Endogenous Growth,” Journal of Public Economic Theory, 15 (December 2013), 939–67.

Mullahy, John, and Stephanie A. Robert, “No Time to Lose: Time Constraints and Physical Activity in the Production of Health,” Review of Economics of the Household, 8 (December 2010), 409–32.

Oreopoulos, Philip, Mark Stabile, Rand Walld, and Leslie Roos, “Short, Medium, and Long-Term Consequences of Poor Infant Health: An Analysis using Siblings and Twins,” Journal of Human Resources, 43 (March 2008), 88–138.

Osang, Thomas, and Jayanta Sarkar, “Endogenous Mortality, Human Capital and Endogenous Growth.” Journal of Macroeconomics, 30 (December 2008), 1423–45.

Paxson, Christina H., and Norbert Schady, “Cognitive Development among Young Children in Ecuador: The Roles of Wealth, Health and Parenting,” Journal of Human Resources, 42 (March 2007), 49–84.

Pelletier, D. L., E. A. Frongillo, J-P. Habicht, “Epidemiologic Evidence for a Potentiating Effect of Malnutrition on Child Mortality,” American Journal of Public Health, 83 (December 2003), 1130–33.

Powdthavee, Nattavudh, and Anna Vignoles, “Mental Health of Parents and Life Satisfaction of Children: A within-Family Analysis of Intergenerational Transmission of Well-being,” Social Indicators Research, 88 (September 2008), pages 397–422.

Ricci, Francesco, and Marios Zachariadis, “Education Externalities on Longevity,” Economica, 80 (July 2013), 404–40.

Salm, Martin, and Daniel Schunk, “The Role of Childhood Health for the Intergenerational Transmission of Human Capital: Evidence from Administrative Data,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 3646 (August 2008).

Schultz, T. Paul, “Productive Benefits of Health: Evidence from Low-Income Countries,” in Health and Economic Growth: Findings and Policy Implications, ed. by Guillem Ló pez-Casasnovas, Berta Rivera, and Luis Currais, MIT Press (Cambridge, Mass.: 2005).

Silles, Mary A., “The Causal Effect of Education on Health: Evidence from the United Kingdom,” Economics of Education Review, 28 (February 2009), 122–28.

Smith, James P., “The Impact of Childhood Health on Adult Labor Market Outcomes,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 91 (August 2009), 478–89.

Smith, Lisa C., and Lawrence Haddad, “Explaining Child Malnutrition in Developing Countries: A Cross-Country Analysis,” Research Report No. 111, International Food Policy Research Institute (May 2000).

Soares, Rodrigo R., “The Effect of Longevity on Schooling and Fertility: Evidence from the Brazilian Demographic and Health Survey,” Journal of Population Economics, 19 (February 2006), 71–97.

Summers, Lawrence H., Investing in All the People: Educating Women in Developing Countries, World Bank (Washington, D.C.: 1994).

Tamura, Robert, “Human Capital and Economic Development,” Journal of Development Economics, 79 (January 2006), 26–72.

Tang, Kam Ki, and Jie Zhang, “Health, Education, and Life Cycle Savings in the Development Process,” Economic Inquiry, 45 (July 2007), 615–30.

Taylor, Beck A., Eric Dearing, and Kathleen McCartney, “Incomes and Outcomes in Early Childhood,” Journal of Human Resources, 39 (December 2004), 980–1007.

Thuilliez, Josselin, “Malaria and Primary Education: A Cross-country Analysis on Repetition and Completion Rates,” Revue d’économie du développement , 2 (December 2009), 127–57.

United Nations, Accelerating Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Africa, Africa Human Development Report (New York: 2016).

Wagstaff, Adam, and Mariam Claeson, The Millennium Development Goals for Health: Rising to the Challenges, World Bank (Washington DC: 2004).

Zhang, Junsen, and Jie Zhang, “The Effect of Life Expectancy on Fertility, Saving, Schooling and Economic Growth: Theory and Evidence,” Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107 (March 2005), 45–66.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Agénor, PR. (2019). Health and Knowledge Externalities: Implications for Growth and Public Policy. In: Bucci, A., Prettner, K., Prskawetz, A. (eds) Human Capital and Economic Growth. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21599-6_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21599-6_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-21598-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-21599-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)