Abstract

This study investigates string-identical gapping constructions with different prosodic phrasings and reports the results of a perception test that seeks to pinpoint the prosodic constraints on gapping constructions. We suggest that unacceptability judgments for Forward Gapping (FG) and Backward Gapping (BG) cannot be analyzed purely through word-order restrictions. The information structural status of the shared, discourse-given constituent and the prominent contrastive constituents play a crucial role. Phonological phrasing patterns, induced by information structural units, interplay with word order restrictions and save the structures noted as unacceptable in the literature. The findings indicate that prosody does not work on the output of syntax but works in tandem with syntactic mechanism. This study further reveals that FG and BG cannot be variations of the same derivational mechanism and we propose a copy analysis for FG, and Multiple Dominance (MD) analysis for BG.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

The abbreviations used in this paper are as follows: ABL ‘Ablative’; ACC ‘Accusative’; ATB ‘Across the Board Movement’; BG ‘Backward Gapping’; CF ‘Contrastive focus’; CT ‘Contrastive topic’; DA ‘Discourse anaphoric’; DAT ‘Dative’; DF ‘Domain of focus’; F ‘Focus’; FG ‘Forward Gapping’; GEN ‘Genitive’; IMPF ‘Imperfect’; IP ‘Intonational phrase’; LOC ‘Locative’; MD ‘Multiple Dominance’; Mod ‘Modality’; NEG ‘Negation’; NOML ‘Nominalizer’; PAST ‘Past’; PERF ‘Perfect’; PL ‘Plural’; PPh ‘Phonological phrase’; PWd ‘Prosodic word’; PROG ‘Progressive’; RNR ‘Right node raising’; SG ‘Singular’.

- 2.

da is a focus/topic marker that cliticizes to the end of the first word, see Göksel and Özsoy 2003.

- 3.

We use the term ‘gapping’ but we do not assume an elided position at PF or take the mechanism behind FG and BG construction as the same.

- 4.

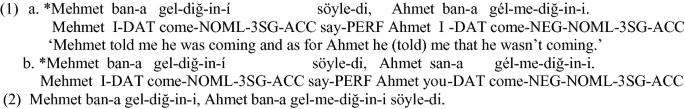

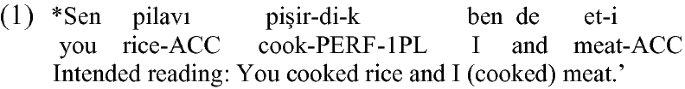

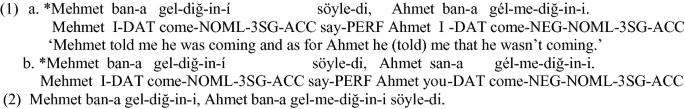

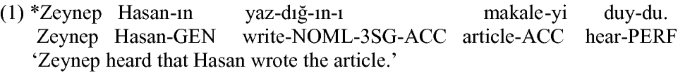

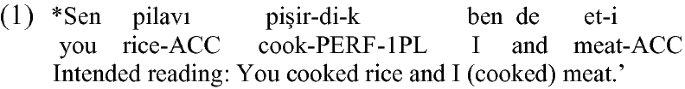

To show that FG and BG are different, Hankamer (1971: 104, 107) further gives the following examples. FG constructions do not show the same properties with BG constructions. Unlike indirect objects with or without contrastive stress yields FG illicit as in (1) but not with BG, as in (2)

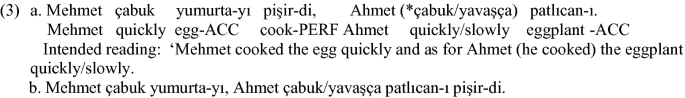

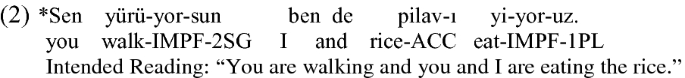

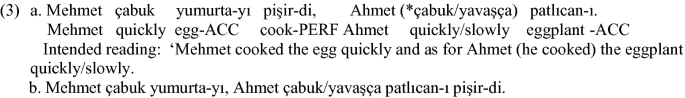

In FG constructions, nonsimilar adverbs cannot surface in both conjuncts and if we have the same adverb in both conjuncts only one can surface as in (3a). However in BG constructions nonsimilar adverbs can surface as in (3b) and gapping of the like adverbs is not obligatory.

- 5.

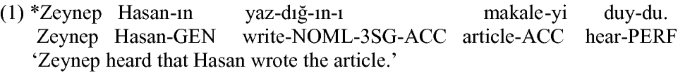

Additionally, if FG is a root phenomenon in the line of the analysis of Ince (2009), the following FG construction needs explanation. Deletion occurs in both conjuncts and in a discontinuous way.

- 6.

BP stands for Boolean Phrase, and B stands for the Boolean Conjunction.

- 7.

Kornfilt (2010) further gives illicit rightward movement operations of constituents out of embedded clauses as an empirical evidence for PFC.

In line with our analysis of gapping constructions, we suggest that the unacceptability of the construction is due to an illicit phrasing pattern in which the dislocated object is interpreted as the complement of the matrix verb. When the prominence is on the matrix predicate and on the embedded subject, the construction becomes acceptable. Hence, there is no need for the PFC constraint as long as prosody collaborates with syntax.

- 8.

Gürer (2015) proposes that CT phrases are base generated in the vP domain. However, they move to the higher Topic position, out of the domain of focus (DF) phrases. The alternative set of sets of propositions of CT is built on alternative sets of focus phrases. Information structural units that remain within the scope DF are aboutness topic and DA phrases which cannot evoke alternatives. In a sense CT has to move out of the scope domain of CF to evoke alternatives.

- 9.

We cannot claim that this was the pitch contours assumed by the authors of the above mentioned papers, but can only assume that this was the case, given the judgements.

- 10.

Kan (2009) proposes an IP level for Turkish based on (i) boundary tone placement, (ii) linguistic pause distribution, (iii) head prominence, and (iv) phrase-final lengthening of vowels.

- 11.

We are not claiming that this is the prosodic pattern assumed in Kornfilt (2010). We simply want to point out contrastive phonological phrasings that make string-identical sentences acceptable or unacceptable.

- 12.

We discuss the prosodic domains of elliptical clauses based on the identification of pre-nuclear, nuclear, and post-nuclear domains as identified by Kamali (2011). Kamali (2011) identifies the prosodic properties of these domains in Turkish in the following way. With an SOV structure, in broad focus condition, in the subject surfaces in the pre-nuclear domain. At the right edge of the pre-nuclear domain a H boundary tone is realized. In the nuclear domain, if the constituent bears final stress, a plateau is observed followed by a fall starting with the onset of the verb. If the constituent in the nuclear domain is lexically accented the fall starts earlier following the accented syllable of the word. In the post nuclear domain, a lower reference height is retained till the end of the utterance.

- 13.

One of the reviewers notes that the unacceptability of FG constructions can be taken as the failure of PF, and hence the Y model can still be maintained. We suggest otherwise, namely, that prosody interferes with the syntactic structure by assigning the object in question to the complement position of the (second) embedded clause rather than to the complement position of the matrix clause. In contrast, the Y model would have produced two consecutive structures and one would then have to be eliminated, thus any model in which prosody works on the output of syntax would derive redundant (ungrammatical) structures. See also the discussion on BG with a shared verb bearing plural agreement markers, for further evidence.

- 14.

The gapped position may alternatively refer back to ‘use of uranium’ but here we are focusing on the reading where it refers to ‘uranium’.

- 15.

Kornfilt (2010) suggests that with BG distributive reading is weak for some speakers.

- 16.

Ince (2009) takes a similar BG structure as ungrammatical in his study; however this construction is fully acceptable for us.

- 17.

For Korean, Chung (2004) shows that BG feeds plurality dependent expressions, indicating that the subjects in both conjuncts act as licensers, a point which gives empirical support to the MD analysis.

- 18.

As the functional projections that we assume between TopP and vP are irrelevant to the scope of this paper and do not have an effect on the analysis, from now on we will show only TopP and vP categories in the tree structures to save space.

- 19.

In this and subsequent representations, we indicate the intervening phrasal projections by horizontal dots.

- 20.

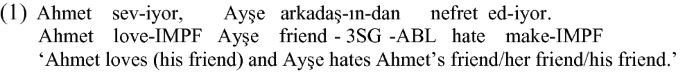

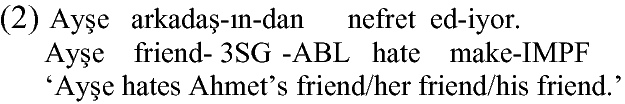

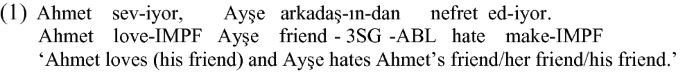

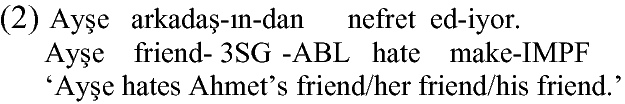

One of the reviewers notes that a sloppy reading is possible with gapping constructions, which casts doubts on the validity of the MD hypothesis. In the following example, the single copy has many possible referents.

We agree with the reviewer regarding the sloppy reading with such gapping constructions. However the same sloppy reading is available even in the absence of gapping.

Hence we suggest that this is a general property of the structure in which the possessive suffix occurs.

- 21.

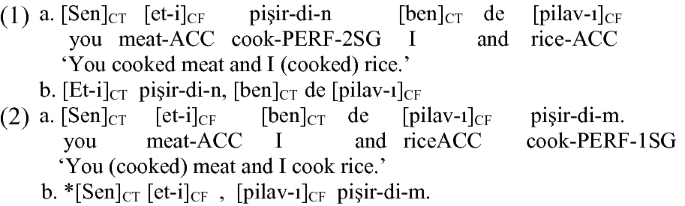

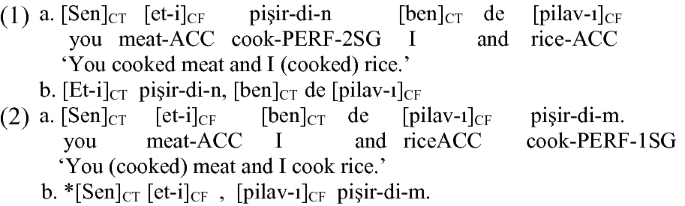

FG is possible even when one of the contrasting pairs is dropped. As illustrated in (1b) pro drop is possible as a result of which we end up with (S)OV&SO. However this is not possible in BG (2b) which further indicates that BG and FG cannot have the same derivational mechanism.

- 22.

The following structure is illicit in FG. Remember that it is equivalent in BG is fully acceptable.

We suggest that this construction is out because the system does not allow ungrammatical sentences at any stage of the derivation. This example further indicates that the derivation of FG is not the same as that of BG.

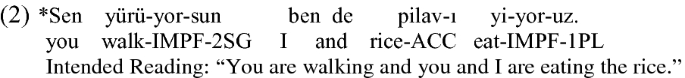

The current analysis has predictions for other coordinated clauses as well. The following construction is unacceptable, even if we put focus on the verb in the second conjunct. Remember that we propose the plural agreement marker bearing verb to be in a position c-commanding both subjects.

The unacceptability of this construction is due to an agreement clash between the plural agreement bearing verb in the second conjunct and the singular agreement bearing verb in the first conjunct.

References

Abe, Jun. 1996. Ellipsis: Deletion, copying or both? In Keio studies in theoretical linguistics I, ed. Yuji Nishiyama, and Yukio Otsu, 49–87. Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies, Keio University.

Abe, Jun, and Hiroto, Hoshi. 1999. Directionality of movement in ellipsis resolution in English and Japanese ellipsis. In Fragments: Studies in ellipsis and gapping, ed. Shalom Lappin and Elabbas Benmamoun, 193–226. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Büring, Daniel. 2013. Givenness, contrast and topic, prosody and information status. Paper presented at 35th Annual Conference of the German Linguistic Society (DGfS), Potsdam University.

Bozşahin, Cem. 2000. Gapping and word order in Turkish. In Studies in Turkish Linguistics: Proceedings of ICTL 10, ed. A. Sumru Özsoy, Didar Akar, Mine Nakipoğlu-Demiralp, E. Eser Erguvanlı-Taylan, and Ayhan Aksu-Koç, 95–104. İstanbul: Boğaziçi University Press.

Chung, Daeho. 2004. A multiple dominance analysis of right node sharing constructions. Language Research 40 (4): 791–811.

Constant, Noah. 2014. Contrastive topic: Meanings and realizations. PhD thesis, UMass Amherst.

Culicover, Peter, and Jackendoff, Ray. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford University Press.

Emre, Ahmet Cevat. 1931. Yeni bir gramer metodu hakkında layıha. İstanbul: Devlet Matbaası.

Erguvanlı, E. Eser. 1984. The function of word order in Turkish grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Frascarelli, Mara. 1997. The phonology of focus and topic in Italian. The Linguistic Review 14: 221–248.

Göksel, Aslı. 1998. Linearity, focus, and the postverbal position in Turkish. In The Mainz meeting, ed. Lars Johanson, Éva Ágnes Csató, Vanessa Locke, Astrid Menz, and Deborah Winterling, 85–106. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

Göksel, Aslı. 2011. A phono-syntactic template for Turkish; Base-generating free word order. In Syntax and morphology multidimensional, ed. Andreas Nolda and Oliver Teuber, 45–76. Mouton de Gruyter.

Göksel, Aslı and Özsoy, A. Sumru. 2000. Is there a focus position in Turkish? In Studies on Turkish and Turkic languages: Proceedings of the ninth international conference on Turkish linguistics, ed. Aslı Göksel, and Celia Kerslake, 219–228. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Göksel, Aslı, and Özsoy, A. Sumru. 2003. dA as a focus/topic associated clitic in Turkish. Lingua, Special issue on Focus in Turkish, ed. A. Sumru Özsoy and Aslı Göksel, 1143–1167.

Güneş, Güliz. 2012. On the role of prosodic constituency in Turkish. In The proceedings of WAFL 8. Cambridge MA: MITWPL.

Gürer, Aslı. 2015. Semantic, prosodic and syntactic marking of information structural units in Turkish. PhD thesis, Boğaziçi University.

Hankamer, Jorge. 1971. Constraints on deletion in syntax. PhD thesis, Yale University.

Ince, Atakan. 2009. Dimensions of ellipsis: Investigations in Turkish. PhD thesis, University of Maryland.

Johnson, Kyle. 1996/2004. In search of the English middle field. Ms., UMass at Amherst, MA.

Johnson, Kyle. 2004. How to be quiet. Paper presented at CLS 40.

Johnson, Kyle. 2006. Gapping is not (VP) ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (2): 289–328.

Kabagema-Bilan, Elena, López-Jiménez, Beatriz and Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2011. Multiple focus in Mandarin Chinese. Lingua, 121: 1890–1905.

Kabak, Barış, and Vogel, Irene. 2001. The phonological word and stress assignment in Turkish. Phonology 18: 315–360.

Kamali, Beste. 2011. Topics at the PF interface of Turkish. PhD thesis, Harvard University.

Kan, Seda. 2009. Prosodic domains and the syntax-prosody mapping in Turkish. MA thesis, Boğaziçi University.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2000. Directionality of identical verb deletion in Turkish coordination. In Jorge Hankamer WebFest. http://ling.ucsc.edu/Jorge/kornfilt.html.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2010. Remarks on some word order facts and Turkish coordination with identical verb ellipsis. In Trans-Turkic studies: Festschrift in honour of Marcel Erdal, ed. Matthias Kappler, Mark Kirchner, and Peter Zieme, 187–221. İstanbul: Kitap Matbaası.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2012. Revisiting ‘suspended affixation’ and other coordinate mysteries. In Functional heads: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Laura Brugé, Anna Cardinaletti, Giuliana Giusti, Nicola Munaro, and Cecilia Poletto, 181–196. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kural, Murat. 1993. Properties of scrambling in Turkish. Ms., UCLA.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2016. Ellipsis: A survey of analytical approaches. In The Oxford handbook of ellipsis, ed. Jeroen van Craenenbroeck, and Tanja Temmerman. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Molnár, Valéria, and Winkler, Susanne. 2010. Edges and gaps: Contrast at the interfaces. Lingua 120: 1392–1415.

Neeleman, Ad, and Vermeulen, Reiko. 2012. The Syntax of topic, focus and contrast: An interface based approach. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Nunes, Jairo. 2004. Linearization of chains and sideward movement. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Phillips, Colin. 1996. Order and structure. PhD thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Richards, Norvin. 2016. Contiguity theory. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Repp, Sophie. 2005. Interpreting ellipsis: The changeable presence of the negation in gapping. PhD thesis, Humboldt University.

Repp, Sophie. 2009. Negation in gapping. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rooth, Mats. 1995. Focus. In The handbook of contemporary semantic theory, ed. Shalom Lappin, 271–298. Oxford: Blackwell.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1984. Phonology and syntax: The relation between sound and structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1995. Sentence prosody: Intonation, stress, and phrasing. In The handbook of phonological theory, ed. John A. Goldsmith, 550–569. Cambridge, MA, and Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Swingle, Kari. 1993. The role of prosody in right node raising. In Syntax at Santa Cruz 2, ed. Geoffrey Pullum, and Eric Potsdam, 82–112. California: Linguistics Research Center.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1995. Phonological phrases: Their relation to syntax, focus, and prominence. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gürer, A., Göksel, A. (2019). (Prosodic-) Structural Constraints on Gapping in Turkish. In: Özsoy, A. (eds) Word Order in Turkish. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 97. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11385-8_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11385-8_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-11384-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-11385-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)