Abstract

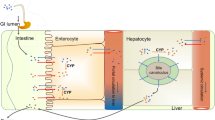

The fate of xenobiotics, and therefore the efficacy or toxicity of chemotherapeutics, may be dictated by the action of metabolizing enzymes. The metabolism of drugs is categorized into reactions that chemically modify a compound (phase 1) or conjugate a compound with a small reactive biomolecules to yield a polar product amenable to excretion (phase 2). While oxidation by cytochrome P450 enzymes is the primary route of metabolism for many drugs, many additional enzymes may modify the structure and thus function of a wide range of agents. The primary function of these non-CYP enzymes may be detoxification, which may coexist with an endogenous biochemical function. While drug metabolism can lead to a loss of efficacy, there are also numerous commonly used cancer chemotherapeutic agents where metabolism is essential for the generation of the active compound. This review outlines what is known about the metabolism of anticancer drugs by non-CYP enzymes and discusses the potential impact of gene expression and genotypic variation of metabolizing enzymes on efficacy and toxicity.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Vasiliou V, Nebert DW (2005) Analysis and update of the human aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene family. Hum Genomics 2(2):138–143

Dockham PA, Lee M-O, Sladek NE (1992) Identification of human liver aldehyde dehydrogenases that catalyze the oxidation of aldophosphamide and retinaldehyde. Biochem Pharmacol 43:2453–2469

Sladek NE (1999) Aldehyde dehydrogenase-mediated cellular relative insensitivity to the oxazaphosphorines. Curr Pharm Des 5:607–625

Sreerama L, Sladek NE (1993) Identification and characterization of a novel class 3 aldehyde dehydrogenase overexpressed in a human breast adenocarcinoma cell line exhibiting oxazaphosphorine-specific acquired resistance. Biochem Pharmacol 45(12):2487–2505

Dockham PA, Sreerama L, Sladek NE (1997) Relative contribution of human erythrocyte aldehyde dehydrogenase to the systemic detoxification of the oxazaphosphorines. Drug Metab Dispos 25(12):1436–1441

Magni M et al (1996) Induction of cyclophosphamide-resistance by aldehyde-dehydrogenase gene transfer. Blood 87:1097–1103

Moreb JS et al (2000) Expression of antisense RNA to aldehyde dehydrogenase class-1 sensitizes tumor cells to 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 293(2):390–396

Sladek NE et al (2002) Cellular levels of aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1) as predictors of therapeutic responses to cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy of breast cancer: a retrospective study. Rational individualization of oxazaphosphorine-based cancer chemotherapeutic regimens. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 49(4):309–21

Ekhart C et al (2008) Influence of polymorphisms of drug metabolizing enzymes (CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, GSTA1, GSTP1, ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1) on the pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide and 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide. Pharmacogenet Genomics 18(6):515–23

Ginestier C et al (2007) ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell 1:555–567

Tanei T et al (2009) Association of breast cancer stem cells identified by aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 expression with resistance to sequential Paclitaxel and epirubicin-based chemotherapy for breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res 15(12):4234–41

Tweedie DJ et al (1991) Metabolism of azoxy derivatives of procarbazine by aldehyde dehydrogenase and xanthine-oxidase. Drug Metab Dispos 19(4):793–803

Yoshida A et al (1998) Human aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. Eur J Biochem 251:549–557

Moreb JS et al (2005) Retinoic acid down-regulates aldehyde dehydrogenase and increases cytotoxicity of 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide and acetaldehyde. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312(1):339–345

Mani C, Hodgson E, Kupfer D (1993) Metabolism of the antimammary cancer antiestrogenic agent tamoxifen. 2. flavin-containing monooxygenase-mediated N- oxidation. Drug Metab Dispos 21(4):657–661

Mani C, Kupfer D (1991) Cytochrome-P-450-mediated activation and irreversible binding of the antiestrogen tamoxifen to proteins in rat and human liver - possible involvement of flavin-containing monooxygenases in tamoxifen activation. Cancer Res 51(22):6052–6058

Yeung CK et al (2000) Immunoquantitation of FMO1 in human liver, kidney, and intestine. Drug Metab Dispos 28(9):1107–11

Hodgson E et al (2000) Flavin-containing monooxygenase isoform specificity for the N- oxidation of tamoxifen determined by product measurement and NADPH oxidation. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 14(2):118–120

Overby LH, Carver GC, Philpot RM (1997) Quantitation and kinetic properties of hepatic microsomal and recombinant flavin-containing monooxygenases 3 and 5 from humans. Chem Biol Interact 106:29–45

Furnes B, Schlenk D (2004) Evaluation of xenobiotic N- and S-oxidation by variant flavin-containing monooxygenase 1 (FMO1) enzymes. Toxicol Sci 78(2):196–203

Hines RN et al (2003) Genetic variability at the human FMO1 locus: significance of a basal promoter yin yang 1 element polymorphism (FMO1*6). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306(3):1210–8

Parte P, Kupfer D (2005) Oxidation of tamoxifen by human flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) 1 and FMO3 to tamoxifen-N-oxide and its novel reduction back to tamoxifen by human cytochromes P450 and hemoglobin. Drug Metab Dispos 33(10):1446–1452

Wang LF et al (2008) Identification of the human enzymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of dasatinib: An effective approach for determining metabolite formation kinetics. Drug Metab Dispos 36(9):1828–1839

Cashman JR (2008) Role of flavin-containing monooxgenase in drug development. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 4(12):1507–1521

Pritsos CA (2000) Cellular distribution, metabolism and regulation of the xanthine oxidoreductase enzyme system. Chem Biol Interact 129:195–208

Morpeth FF (1982) Studies on the specificity toward aldehyde substrates and steady-state kinetics of xanthine oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta 744:328–334

Gustafson DL, Pritsos CA (1992) Bioactivation of Mitomycin-C by xanthine dehydrogenase from Emt6 mouse mammary-carcinoma tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 84(15):1180–1185

Yee SB, Pritsos CA (1997) Comparison of oxygen radical generation from the reductive activation of doxorubicin, streptonigrin, and menadione by xanthine oxidase and xanthine dehydrogenase. Arch Biochem Biophys 347(2):235–241

Yee SB, Pritsos CA (1997) Reductive activation of doxorubicin by xanthine dehydrogenase from EMT6 mouse mammary carcinoma tumors. Chem Biol Interact 104:87–101

KeuzenkampJansen CW et al (1996) Metabolism of intravenously administered high-dose 6- mercaptopurine with and without allopurinol treatment in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 18(2):145–150

Lewis AS et al (1984) Inhibition of mammalian xanthine-oxidase by folate compounds and amethopterin. J Biol Chem 259(1):12–15

Innocenti F et al (1996) Clinical and experimental pharmacokinetic interaction between 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 37(5):409–414

Lennard L (1992) The clinical pharmacology of 6-mercaptopurine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 43(4):329–339

Parks DA, Granger DN (1986) Xanthine oxidase: Biochemistry, distribution and physiology. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 126(Suppl):87–99

Sarnesto A, Linder N, Raivio KO (1996) Organ distribution and molecular forms of human xanthine dehydrogenase/xanthine oxidase protein. Lab Invest 74(1):48–56

Malle E et al (2007) Myeloperoxidase: a target for new drug development? Br J Pharmacol 152:838–854

Kagan VE et al (1999) Mechanism-based chemopreventive strategies against etoposide-induced acute myeloid leukemia: Free radical/antioxidant approach. Mol Pharmacol 56(3):494–506

Kagan VE et al (2001) Pro-oxidant and antioxidant mechanisms of etoposide in HL-60 cells: role of myeloperoxidase. Cancer Res 61(21):7777–7784

Fan Y et al (2006) Myeloperoxidase-catalyzed metabolism of etoposide to its quinone and glutathione adduct forms in HL60 cells. Chem Res Toxicol 19(7):937–943

Jordan CGM et al (1999) Aldehyde oxidase-catalysed oxidation of methotrexate in the liver of guinea-pig, rabbit and man. J Pharm Pharmacol 51(4):411–418

Roy SK et al (1995) Human liver oxidative-metabolism of O-6-benzylguanine. Biochem Pharmacol 50(9):1385–1389

Bobola MS et al (1996) Role of O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in resistance of human brain-tumor cell-lines to the clinically relevant methylating agents temozolomide and streptozotocin. Clin Cancer Res 2(4):735–741

Berger R et al (1984) Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency leading to thymine-uraciluria. An inborn error of pyrimidine metabolism. Clin Chim Acta 141(2–3):227–234

Lu ZH, Zhang R, Diasio RB (1992) Purification and characterization of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase from human liver. J Biol Chem 267(24):17102–17109

Montfort WR, Weichsel A (1997) Thymidylate synthase: structure, inhibition, and strained conformations during catalysis. Pharmacol Ther 76(1–3):29–43

Ho DH et al (1986) Distribution and inhibition of dihydrouracil dehydrogenase activities in human tissues using 5-fluorouracil as a substrate. Anticancer Res 6(4):781–784

Naguib FN, el Kouni MH, Cha S (1985) Enzymes of uracil catabolism in normal and neoplastic human tissues. Cancer Res 45(11 Pt 1):5405–5412

Lu Z, Zhang R, Diasio RB (1993) Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and liver: population characteristics, newly identified deficient patients, and clinical implication in 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. Cancer Res 53(22):5433–5438

Van Kuilenburg AB et al (1999) Profound variation in dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity in human blood cells: major implications for the detection of partly deficient patients. Br J Cancer 79(3–4):620–626

Etienne MC et al (1994) Population study of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 12(11):2248–2253

Ridge SA et al (1998) Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase pharmacogenetics in Caucasian subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 46(2):151–156

Ridge SA et al (1998) Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase pharmacogenetics in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 77(3):497–500

Van Kuilenburg ABP et al (1999) Genotype and phenotype in patients with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. Hum Genet 104(1):1–9

Johnson MR et al (1997) Structural organization of the human dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene. Cancer Res 57(9):1660–1663

Shestopal SA, Johnson MR, Diasio RB (2000) Molecular cloning and characterization of the human dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase promoter. Biochim Biophys Acta 1494(1–2):162–169

Wei X et al (1998) Characterization of the human dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene. Genomics 51(3):391–400

Takai S, et al. (1994) Assignment of the human dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene (DPYD) to chromosome region 1p22 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genomics, 24(3 AD - Department of Genetics, International Medical Center of Japan, Tokyo UR - PM:7713523):613–614

Collie-Duguid ES et al (2000) Known variant DPYD alleles do not explain DPD deficiency in cancer patients. Pharmacogenetics 10(3):217–223

Johnson MR, Wang K, Diasio RB (2002) Profound dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency resulting from a novel compound heterozygote genotype. Clin Cancer Res 8(3):768–774

Mattison LK, Johnson MR, Diasio RB (2002) A comparative analysis of translated dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase cDNA; conservation of functional domains and relevance to genetic polymorphisms. Pharmacogenetics 12(2):133–144

McLeod HL et al (1998) Nomenclature for human DPYD alleles. Pharmacogenetics 8(6):455–459

Vreken P et al (1996) A point mutation in an invariant splice donor site leads to exon skipping in two unrelated Dutch patients with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Disorders 19(5):645–654

Vreken P et al (1997) Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) deficiency: identification and expression of missense mutations C29R, R886H and R235W. Hum Genet 101(3):333–338

Vreken P, et al. (1997) Identification of novel point mutations in the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene. J Inher Metab Disorders, 20(3 AD - University of Amsterdam, Department of Pediatrics, The Netherlands UR - PM:9266349): 335–338

Grem JL (2002) 5-Fluoropyrimidines. In: Chabner BA, Longo DL (eds) Cancer chemotherapy and biotherapy. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, pp 149–211

Diasio RB (1998) The role of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) modulation in 5-FU pharmacology. Oncology 12(10 Suppl 7):23–27

Heggie GD et al (1987) Clinical pharmacokinetics of 5-fluorouracil and its metabolites in plasma, urine, and bile. Cancer Res 47(8):2203–2206

Fleming RA et al (1992) Correlation between dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase-activity in peripheral mononuclear-cells and systemic clearance of fluorouracil in cancer-patients. Cancer Res 52:2899–2902

Levy E et al (1998) Toxicity of fluorouracil in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: effect of administration schedule and prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol 16(11):3537–3541

Yen JL, McLeod HL (2007) Should DPD analysis be required prior to prescribing fluoropyrimidines? Eur J Cancer 43(6):1011–1016

Schwab M et al (2008) Role of genetic and nongenetic factors for fluorouracil treatment-related severe toxicity: a prospective clinical trial by the German 5-FU toxicity study group. J Clin Oncol 26(13):2131–2138

Zhang R et al (1993) Relationship between circadian-dependent toxicity of 5-fluorodeoxyuridine and circadian rhythms of pyrimidine enzymes: possible relevance to fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Cancer Res 53(12):2816–2822

de Bono JS, Twelves CJ (2001) The oral fluorinated pyrimidines. Invest New Drugs 19(1):41–59

Lamont EB, Schilsky RL (1999) The oral fluoropyrimidines in cancer chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 5(9):2289–2296

Adjei AA et al (2002) Comparative pharmacokinetic study of continuous venous infusion fluorouracil and oral fluorouracil with eniluracil in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 20(6):1683–1691

Baccanari DP et al (1993) 5-Ethynyluracil (776C85): a potent modulator of the pharmacokinetics and antitumor efficacy of 5-fluorouracil. Proc Natl Acad Sci 90(23):11064–11068

Grem JL et al (2000) Phase I and pharmacokinetic trial of weekly oral fluorouracil given with eniluracil and low-dose leucovorin to patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 18(23):3952–3963

Cohen SJ et al (2002) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of once daily oral administration of S-1 in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 8(7):2116–2122

van Groeningen CJ et al (2000) Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of oral S-1 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 18(14):2772–2779

Sakuramoto S et al (2007) Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. New Engl J Med 357:1810–1820

Damle B et al (2001) Effect of food on the oral bioavailability of UFT and leucovorin in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 7(3):517–523

Sadahiro S et al (2001) A pharmacological study of the weekday-on/weekend-off oral UFT schedule in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 47(5):457–460

Douillard JY et al (2002) Multicenter phase III study of uracil/tegafur and oral leucovorin versus fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 20(17):3605–3616

Lembersky BC, et al (2004) Oral uracil and tegafur plus leucovorin compared with intravenous fluorouracil and leucovorin in stage II and III carcinoma of the colon: Results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol C-06. in 40th Annual Meeting of the American-Society-of-Clinical-Oncology. New Orleans, LA: Amer Soc Clinical Oncology

Miwa M et al (1998) Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumours by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Cancer 34(8):1274–1281

Schuller J et al (2000) Preferential activation of capecitabine in tumor following oral administration to colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 45(4):291–297

Hoff PM et al (2001) Comparison of oral capecitabine versus intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin as first-line treatment in 605 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19(8):2282–2292

Van Cutsem E et al (2001) Oral capecitabine compared with intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a large phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19(21):4097–4106

Largillier R et al (2006) Pharmacogenetics of capecitabine in advanced breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 12(18):5496–5502

Salgado J et al (2007) Polymorphisms in the thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase genes predict response and toxicity to capecitabine-raltitrexed in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep 17(2):325–328

Pacifici GM et al (1991) Thiopurine methyltransferase in humans: development and tissue distribution. Dev Pharmacol Ther 17(1–2):16–23

Elion GB (1967) Symposium on immunosuppressive drugs. Biochemistry and pharmacology of purine analogues. Feder Proc 26(3):898–904

Remy CN (1963) Metabolism of thiopyrimidines and thiopurines: S-methylation with S-adenosylmethionine transmethylase and catabolism in mammalian tissue. J Biol Chem 238:1078–1084

Weinshilboum RM, Sladek SL (1980) Mercaptopurine pharmacogenetics: monogenic inheritance of erythrocyte thiopurine methyltransferase activity. Am J Hum Genet 32(5):651–662

Coulthard SA et al (1998) The relationship between thiopurine methyltransferase activity and genotype in blasts from patients with acute leukemia. Blood 92(8):2856–2862

McLeod HL et al (1995) Polymorphic thiopurine methyltransferase in erythrocytes is indicative of activity in leukemic blasts from children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 85(7):1897–1902

Van Loon JA, Weinshilboum RM (1982) Thiopurine methyltransferase biochemical genetics: human lymphocyte activity. Biochem Genet 20(7–8):637–658

Van Loon JA, Weinshilboum RM (1990) Thiopurine methyltransferase isozymes in human renal tissue. Drug Metab Dispos 18(5):632–638

Woodson LC, Dunnette JH, Weinshilboum RM (1982) Pharmacogenetics of human thiopurine methyltransferase: kidney- erythrocyte correlation and immunotitration studies. J Pharmaco Exp Ther 222(1):174–181

McLeod HL et al (1995) Higher activity of polymorphic thiopurine S-methyltransferase in erythrocytes from neonates compared to adults. Pharmacogenetics 5(5):281–286

Lennard L et al (1990) Genetic variation in response to 6-mercaptopurine for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet 336(8709):225–229

Szumlanski C et al (1996) Thiopurine methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: human gene cloning and characterization of a common polymorphism. DNA Cell Biol 15(1):17–30

Krynetski EY et al (1997) Promoter and intronic sequences of the human thiopurine S- methyltransferase (TPMT) gene isolated from a human Pac1 genomic library. Pharm Res 14(12):1672–1678

Fotoohi AK, Coulthard SA, Albertioni F (2010) Thiopurines: factors influencing toxicity and response. Biochem Pharmacol 79(9):1211–20

Tai HL et al (1996) Thiopurine S-methyltransferase deficiency: two nucleotide transitions define the most prevalent mutant allele associated with loss of catalytic activity in Caucasians. Am J Hum Genet 58(4):694–702

McLeod HL et al (2000) Genetic polymorphism of thiopurine methyltransferase and its clinical relevance for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 14(4):567–572

Spire-Vayron DIM et al (1999) Characterization of a variable number tandem repeat region in the thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene promote. Pharmacogenetics 9(2):189–198

Keuzenkamp-Jansen CW et al (1996) Detection and identification of 6-methylmercapto-8-hydoxypurine, a major metabolite of 6-mercaptopurine, in plasma during intravenous administration. Clin Chem 42(3):380–6

Kitchen BJ et al (1999) Thioguanine administered as a continuous intravenous infusion to pediatric patients is metabolized to the novel metabolite 8-hydroxy-thioguanine. J Pharmacol Exper Ther 291(2):870–4

Swann PF et al (1996) Role of postreplicative DNA mismatch repair in the cytotoxic action of thioguanine. Science 273(5278):1109–1112

Lowry PW et al (2001) Leucopenia resulting from a drug interaction between azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine and mesalamine, sulphasalazine, or balsalazide. Gut 49(5):656–664

Maddocks JL et al (1986) Azathioprine and severe bone marrow depression [letter]. Lancet 1(8473):156

Lennard L et al (1983) Childhood leukaemia: a relationship between intracellular 6-mercaptopurine metabolites and neutropenia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 16(4):359–363

Lennard L, Davies HA, Lilleyman JS (1993) Is 6-thioguanine more appropriate than 6-mercaptopurine for children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia? Br J Cancer 68(1):186–190

Lennard L et al (1987) Thiopurine pharmacogenetics in leukemia: correlation of erythrocyte thiopurine methyltransferase activity and 6- thioguanine nucleotide concentrations. Clin Pharmacol Ther 41(1):18–25

Andersen JB et al (1998) Pharmacokinetics, dose adjustments, and 6- mercaptopurine/methotrexate drug interactions in two patients with thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency. Acta Paediatr 87(1):108–111

Evans WE et al (1991) Altered mercaptopurine metabolism, toxic effects, and dosage requirement in a thiopurine methyltransferase-deficient child with acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Pediatr 119(6):985–989

Lennard L et al (1993) Congenital thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency and 6- mercaptopurine toxicity during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Arch Dis Child 69(5):577–579

Lennard L et al (1997) Thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency in childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia: 6-mercaptopurine dosage strategies. Med Pediatr Oncol 29(4):252–255

McLeod HL, Miller DR, Evans WE (1993) Azathioprine-induced myelosuppression in thiopurine methyltransferase deficient heart transplant recipient. Lancet 341(8853):1151

Relling MV et al (1999) Prognostic importance of 6-mercaptopurine dose intensity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 93(9):2817–2823

Coulthard SA et al (2002) The effect of thiopurine methyltransferase expression on sensitivity to thiopurine drugs. Mol Pharmacol 62(1):102–109

Dervieux T et al (2001) Differing contribution of thiopurine methyltransferase to mercaptopurine versus thioguanine effects in human leukemic cells. Cancer Res 61(15):5810–5816

Erb N, Harms DO, Janka-Schaub G (1998) Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of thiopurines in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia receiving 6-thioguanine versus 6-mercaptopurine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 42(4):266–272

Lancaster DL et al (1998) Thioguanine versus mercaptopurine for therapy of childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia: a comparison of haematological toxicity and drug metabolite concentrations. Br J Haematol 102(2):439–443

Vogt MH et al (1993) The importance of methylthio-IMP for methylmercaptopurine ribonucleoside (Me-MPR) cytotoxicity in Molt F4 human malignant T- lymphoblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 1181(2):189–194

Adamson PC, Poplack DG, Balis FM (1994) The cytotoxicity of thioguanine vs mercaptopurine in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res 18(11):805–810

Lilleyman JS, Lennard L (1996) Non-compliance with oral chemotherapy in childhood leukaemia [editorial]. Br Med J 313(7067):1219–1220

Tan BB et al (1997) Azathioprine in dermatology: a survey of current practice in the U.K. Br J Dermatol 136(3):351–355

Forrest GL, Gonzalez B (2000) Carbonyl reductase. Chem Biol Interact 129:21–40

Kassner N et al (2008) Carbonyl reductase 1 is a predominant doxorubicin reductase in the human liver. Drug Metab Dispos 36(10):2113–2120

Watanabe K et al (1998) Mapping of a novel human carbonyl reductase, CBR3, and ribosomal pseudogenes to human chromosome 21q22.2. Genomics 52(1):95–100

Miura T, Nishinaka T, Terada T (2008) Different functions between human monomeric carbonyl reductase 3 and carbonyl reductase 1. Mol Cell Biochem 315(1–2):113–121

Jacquet J-M et al (1990) Doxorubicin and doxorubicinol: intra- and inter-individual variations of pharmacokinetic parameters. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 27:219–225

Kokenberg E et al (1998) Cellular pharmacokinetics of daunorubicin: relationships with the response to treatment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 6(5):802–812

Morris RG, Kotasek D, Paltridge G (1991) Disposition of epirubicin and metabolites with repeated courses to cancer-patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 40(5):481–487

Mross K et al (1988) Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of epidoxorubicin and doxorubicin in humans. J Clin Oncol 6:517–526

Robert J et al (1987) Pharmacokinetics of idarubicin after daily intravenous administration in leukemia patients. Leuk Res 11:961–964

Tidefelt U, Prenkert M, Paul C (1996) Comparison of idarubicin and daunorubicin and their main metabolites regarding intracellular uptake and effect on sensitive and multidrug-resistant HL60 cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 38:476–480

Forrest GL et al (2000) Human carbonyl reductase overexpression in the heart advances the development of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in transgenic mice. Cancer Res 60(18):5158–5164

Olson LE et al (2003) Protection from doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in mice with a null allele of carbonyl reductase 1. Cancer Res 63(20):6602–6606

Fan L et al (2008) Genotype of human carbonyl reductase CBR3 correlates with doxorubicin disposition and toxicity. Pharmacogenet Genomics 18(7):621–629

Lal S et al (2008) CBR1 and CBR3 pharmacogenetics and their influence on doxorubicin disposition in Asian breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci 99(10):2045–2054

Gonzalez-Covarrubias V et al (2009) Pharmacogenetics of human carbonyl reductase 1 (CBR1) in livers from black and white donors. Drug Metab Dispos 37(2):400–407

Blanco JG et al (2008) Genetic polymorphisms in the carbonyl reductase 3 gene CBR3 and the NAD(P)H : Quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene NQO1 in patients who developed anthracycline-related congestive heart failure after childhood cancer. Cancer 112(12):2789–2795

Choi JY et al (2009) Nitric oxide synthase variants and disease-free survival among treated and untreated Breast cancer patients in a southwest oncology group clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res 15(16):5258–5266

Traver RD et al (1992) NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase gene expression in human colon carcinoma cells: characterization of a mutation which modulates DT-diaphorase activity and mitomycin sensitivity. Cancer Res 52:797–802

Siegel D et al (2001) Rapid polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of a mutant form of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1. Mol Pharmacol 59(2):263–268

Ross D et al (2000) NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): chemoprotection, bioactivation, gene regulation and genetic polymorphisms. Chem Biol Interact 129:77–97

Siegel D et al (1990) Metabolism of mitomycin C by DT-diaphorase: role in mitomycin C-induced DNA damage and cytotoxicity in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 50:7483–7489

Gan YB et al (2001) Expression of DT-diaphorase and cytochrome P450 reductase correlates with mitomycin c activity in human bladder tumors. Clin Cancer Res 7(5):1313–1319

Bailey SM et al (2001) Involvement of NADPH: cytochrome P450 reductase in the activation of indoloquinone EO9 to free radical and DNA damaging species. Biochem Pharmacol 62(4):461–468

Fitzsimmons SA et al (1996) Reductase enzyme expression across the National Cancer Institute tumour cell line panel: Correlation with sensitivity to mitomycin C and EO9. J Natl Cancer Inst 88(5):259–269

Loadman PM et al (2000) Pharmacological properties of a new aziridinylbenzoquinone, RH1 (2,5-diaziridinyl-3-(hydroxymethyl)-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone), in mice. Biochem Pharmacol 59(7):831–837

Schellens JHM et al (1994) Phase-I and pharmacological study of the novel indoloquinone bioreductive alkylating cytotoxic drug E09. J Natl Cancer Inst 86(12):906–912

Dalton JT et al (1991) Pharmacokinetics of intravesical mitomycin C in superficial bladder cancer patients. Cancer Res 51:5144–5152

Siegel D et al (1999) Genotype-phenotype relationships in studies of a polymorphism in NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1. Pharmacogenetics 9(1):113–121

Fleming RA et al (2002) Clinical significance of a NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 polymorphism in patients with disseminated peritoneal cancer receiving intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C. Pharmacogenetics 12(1):31–37

Basu S et al (2004) Immunohistochemical analysis of NAD(P)H : quinone oxidoreductase and NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase in human superficial bladder tumours: Relationship between tumour enzymology and clinical outcome following intravesical mitomycin C therapy. Int J Cancer 109(5):703–709

Kelland LR et al (1999) DT-diaphorase expression and tumor cell sensitivity to 17- allylamino,17-demethoxygeldanamycin, an inhibitor of heat shock protein 90. J Natl Cancer Inst 91(22):1940–1949

Guo WC et al (2005) Formation of 17-allylamino-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) hydroquinone by NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1: Role of 17-AAG hydroquinone in heat shock protein 90 inhibition. Cancer Res 65(21):10006–10015

Goetz MP et al (2005) Phase I trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(6):1078–1087

Fagerholm R et al (2008) NAD(P)H : quinone oxidoreductase 1 NQO1(star)2 genotype (P187S) is a strong prognostic and predictive factor in breast cancer. Nat Genet 40(7):844–853

Powis G et al (1995) Over-expression of DT-diaphorase in transfected NIH 3 T3 cells does not lead to increased anticancer quinone drug-sensitivity - A questionable role for the enzyme as a target for bioreductively activated anticancer drugs. Anticancer Res 15(4):1141–1145

Cummings J et al (1992) The enzymology of doxorubicin quinone reduction in tumor-tissue. Biochem Pharmacol 44(11):2175–2183

Beall HD et al (1994) Metabolism of bioreductive antitumor compounds by purified rat and human DT-diaphorases. Cancer Res 54(12):3196–3201

Mrozek E et al (2008) Phase II study of sequentially administered low-dose mitomycin-C (MMC) and irinotecan (CPT-11) in women with metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Ann Oncol 19(8):1417–1422

Senter PD et al (1996) The role of rat serum carboxylesterase in the activation of paclitaxel and camptothecin prodrugs. Cancer Res 56(7):1471–1474

Morton CL et al (2000) Activation of CPT-11 in mice: Identification and analysis of a highly effective plasma esterase. Cancer Res 60(15):4206–4210

Slatter JG et al (1997) Bioactivation of the anticancer agent CPT-11 to SN-38 by human hepatic microsomal carboxylesterases and the in vitro assessment of potential drug interactions. Drug Metab Dispos 25(10):1157–1164

Wu MH et al (2002) Irinotecan activation by human carboxylesterases in colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res 8(8):2696–2700

Xu G et al (2002) Human carboxylesterase 2 is commonly expressed in tumor tissue and is correlated with activation of irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res 8(8):2605–26111

Wu MH et al (2004) Determination and analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotype structure of the human carboxylesterase 2 gene. Pharmacogenetics 14(9):595–605

Charasson V et al (2004) Pharmacogenetics of human carboxylesterase 2, an enzyme involved in the activation of irinotecan into SN-38. Clin Pharmacol Ther 76(6):528–535

Gupta F et al (1994) Metabolic-fate of irinotecan in humans - correlation of glucuronidation with diarrhea. Cancer Res 54(14):3723–3725

Bouffard DY, Laliberte J, Momparler RL (1993) Kinetic-studies on 2',2'difluorodeoxycytidine (gemcitabine) with purified human deoxycytidine kinase and cytidine deaminase. Biochem Pharmacol 45(9):1857–1861

Mercier C et al (2009) Early severe toxicities after capecitabine intake: possible implication of a cytidine deaminase extensive metabolizer profile. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 63(6):1177–1180

Neff T, Blau A (1996) Forced expression of cytidine deaminase confers resistance to cytosine arabinoside and gemcitabine. Exp Hematol 24(11):1340–1346

Bengala C et al (2005) Prolonged fixed dose rate infusion of gemcitabine with autologous haematopoietic support in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 93(1):35–40

Ciccolini J et al (2010) Cytidine deaminase residual activity in serum is a predictive marker of early severe toxicities in adultsafter gemcitabine-based chemotherapies. J Clin Oncol 28(1):161–165

Gilbert JA et al (2006) Gemcitabine pharmacogenomics: cytidine deaminase and deoxycytidylate deaminase gene resequencing and functional genomics. Clin Cancer Res 12(6):1794–1803

Tibaldi C et al (2008) Correlation of CDA, ERCC1, and XPD polymorphisms with response and survival in gemcitabine/cisplatin - treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 14(6):1797–1803

Sugiyama E et al (2007) Pharmacokinetics of gemcitabine in Japanese cancer patients: the impact of a cytidine deaminase polymorphism. J Clin Oncol 25(1):32–42

Ueno H et al (2009) Homozygous CDA*3 is a major cause of life-threatening toxicities in gemcitabine-treated Japanese cancer patients. Br J Cancer 100(6):870–873

Tukey RH, Strassburg CP (2000) Human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases metabolism, expression and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 40:581–616

Camaggi CM et al (1993) Epirubicin metabolism and pharmacokinetics after conventional-dose and high-dose intravenous administration - a cross-over study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 32(4):301–309

Innocenti F et al (2001) Epirubicin glucuronidation is catalyzed by human UDP- glucuronosyltransferase 2B7. Drug Metab Dispos 29(5):686–692

Innocenti F et al (2000) Flavopiridol metabolism in cancer patients is associated with the occurrence of diarrhea. Clin Cancer Res 6(9):3400–3405

Nishiyama T et al (2002) Reverse geometrical selectivity in glucuronidation and sulfation of cis- and trans-4-hydroxytamoxifens by human liver UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and sulfotransferases. Biochem Pharmacol 63(10):1817–1830

Poon GK et al (1993) Analysis of phase-I and phase-II metabolites of tamoxifen in breast-cancer patients. Drug Metab Dispos 21(6):1119–1124

Ando Y et al (1998) UGT1A1 genotypes and glucuronidation of SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan. Ann Oncol 9(8):845–847

Samokyszyn VM et al (2000) 4-Hydroxyretinoic acid, a novel substrate for human liver microsomal UDP-glucuronosyltransferase(s) and recombinant UGT2B7. J Biol Chem 275(10):6908–6914

Boon PJM, van der Boon D, Mulder GJ (2000) Cytotoxicity and biotransformation of the anticancer drug perillyl alcohol in PC12 cells and in the rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 167(1):55–62

Zhou SF et al (2001) Identification and reactivity of the major metabolite (beta-1- glucuronide) of the anti-tumour agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4- acetic acid (DMXAA) in humans. Xenobiotica 31(5):277–293

Tukey R, Strassburg CP (2001) Genetic multiplicity of the human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases and regulation in the gastrointestinal tract. Mol Pharmacol 59(3):405–414

Ando Y et al (2000) Polymorphisms of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase gene and irinotecan toxicity: a pharmacogenetic analysis. Cancer Res 60(24):6921–6926

Sawyer MB et al (2002) Identification of a polymorphism in the UGT2B7 promoter: Association with morphine glucuronidation in patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 71(2):40–P40

Mackenzie PI, Miners JO, McKinnon RA (2000) Polymorphisms in UDP glucuronosyltransferase genes: Functional consequences and clinical relevance. Clin Chem Lab Med 38(9):889–892

Bhasker CR et al (2000) Genetic polymorphism of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 (UGT2B7) at amino acid 268: ethnic diversity of alleles and potential clinical significance. Pharmacogenetics 10(8):679–685

Huang YH et al (2002) Identification and functional characterization of UDP- glucuronosyltransferases UGT1A8*1, UGT1A8*2 and UGT1A8*3. Pharmacogenetics 12(4):287–297

Bosma PJ et al (1995) The genetic basis of the reduced expression of bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 in Gilbert’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 333(18):1171–1175

Innocenti F et al (2004) Genetic variants in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 gene predict the risk of severe neutropenia of irinotecan. J Clin Oncol 22(8):1382–1388

Hoskins JM et al (2007) UGT1A1*28 genotype and irinotecan-induced neutropenia: dose matters. J Natl Cancer Inst 99(17):1290–1295

Ireson CR et al (2002) Metabolism of the cancer chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat intestine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent 11(1):105–111

Blackburn AC et al (1998) Characterization and chromosome location of the gene GSTZ1 encoding the human Zeta class glutathione transferase and maleylacetoacetate isomerase. Cytogenet Cellular Genet 83(1–2):109–114

Board PG et al (2000) Identification, characterization, and crystal structure of the Omega class glutathione transferases. J Biol Chem 275(32):24798–24806

Board PG, Webb GC (1987) Isolation of a cDNA clone and localization of human glutathione S-transferase 2 genes to chromosome band 6p12. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84(8):2377–2381

Pearson WR et al (1993) Identification of class-mu glutathione transferase genes GSTM1-GSTM5 on human chromosome 1p13. Am J Hum Genet 53(1):220–233

Silberstein DL, Shows TB (1982) Gene for glutathione S-transferase-1 (GST1) is on human chromosome 11. Somat Cell Mol Genet 8(5):667–675

Singhal SS et al (1990) Characterization of a novel alpha-class anionic glutathione S-transferase isozyme from human liver. Arch Biochem Biophys 279(1):45–53

Suzuki T, Board P (1984) Glutathione-S-transferase gene mapped to chromosome 11 is GST3 not GST1. Somatic Cell Mol Genet, 10(3 UR - PM:6585974):319–320

Webb G et al (1996) Chromosomal localization of the gene for the human theta class glutathione transferase (GSTT1). Genomics 33(1):121–123

Xu S et al (1998) Characterization of the human class Mu glutathione S-transferase gene cluster and the GSTM1 deletion. J Biol Chem 273(6):3517–3527

Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR (2005) Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 45(1):51–88

Kanaoka Y et al (2000) Structure and chromosomal localization of human and mouse genes for hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase - conservation of the ancestral genomic structure of sigma-class glutathione S-transferase. Eur J Biochem 267(11):3315–3322

Wang L et al (2005) Cloning, expression and characterization of human glutathione S-transferase Omega 2. Int J Mol Med 16(1):19–27

Morel F et al (2004) Gene and protein characterization of the human glutathione S-transferase Kappa and evidence for a peroxisomal localization*. J Biol Chem 279(16):16246–16253

Safran M, et al (2009) GeneCards. Available from: http://www.genecards.org/

Hayes JD, Pulford DJ (1995) The glutathione S-Transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 30(6):445–600

Hayes JD, Strange RC (2000) Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and their biological consequences. Pharmacology 61(3):154–166

McCarver DG, Hines RN (2002) The ontogeny of human drug-metabolizing enzymes: phase II conjugation enzymes and regulatory mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300(2):361–366

Rebbeck TR (1997) Molecular epidemiology of the human glutathione S-transferase genotypes GSTM1 and GSTT1 in cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent 6(9):733–743

Eaton DL, Bammler TK (1999) Concise review of the glutathione S-transferases and their significance to toxicology. Toxicol Sci 49(2 AD - Department of Environmental Health, University of Washington, Seattle 98195, USA. deaton@u.washington.edu UR - PM:10416260): 156–164

Carder PJ et al (1990) Glutathione S-transferase in human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 16(4):293–303

Wang L et al (2000) Glutathione S-transferase enzyme expression in hematopoietic cell lines implies a differential protective role for T1 and A1 isoenzymes in erythroid and for M1 in lymphoid lineages. Haematologica 85(6):573–579

Den Boer ML et al (1999) Different expression of glutathione S-transferase alpha, mu and pi in childhood acute lymphoblastic and myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol 104(2):321–327

Yin ZL et al (2001) Immunohistochemistry of omega class glutathione S-transferase in human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 49(8):983–987

van Bladeren PJ (2000) Glutathione conjugation as a bioactivation reaction. Chem Biol Interact 129(1–2):61–76

Mannervik B, Danielson UH (1988) Glutathione transferases–structure and catalytic activity. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 23(3):283–337

Hall AG, Tilby MJ (1992) Mechanisms of action of, and modes of resistance to, alkylating agents used in the treatment of haematological malignancies. Blood Rev 6(3):163–173

Panasci L et al (2001) Chlorambucil drug resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the emerging role of DNA repair. Clin Cancer Res 7(3):454–461

Armstrong, R.N., Structure, catalytic mechanism, and evolution of the glutathione transferases (1997) Chem Res Toxicol, 10(1 AD - Department of Biochemistry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, USA. armstrong@toxicology.mc.vanderbilt.edu UR - PM:9074797):2–18

Strange RC et al (1991) The human glutathione S-transferases: a case-control study of the incidence of the GST1 0 phenotype in patients with adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis 12(1):25–28

Hein DW et al (2000) Molecular genetics and epidemiology of the NAT1 and NAT2 acetylation polymorphisms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent 9(1):29–42

Wikman H et al (2001) Relevance of N-acetyltransferase 1 and 2 (NAT1, NAT2) genetic polymorphisms in non-small cell lung cancer susceptibility. Pharmacogenetics 11(2):157–168

Ratain MJ et al (1991) Paradoxical relationship between acetylator phenotype and amonafide toxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther 50:573–579

Ratain MJ et al (1993) Phase-I study of amonafide dosing based on acetylator phenotype. Cancer Res 53(10):2304–2308

Ratain MJ et al (1996) Individualized dosing of amonafide based on a pharmacodynamic model incorporating acetylator phenotype and gender. Pharmacogenetics 6(1):93–101

Acknowledgments

DJ, SAC, and AVB are supported by Cancer Research UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jamieson, D., Coulthard, S.A., Boddy, A.V. (2014). Metabolism (Non-CYP Enzymes). In: Rudek, M., Chau, C., Figg, W., McLeod, H. (eds) Handbook of Anticancer Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9135-4_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9135-4_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-9134-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-9135-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)