Abstract

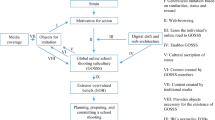

This literature review provides an overview of scholarly debate on the role of media content in the genesis of school shootings. It begins by showing that the idea that media depictions of violence have a general violence-promoting effect is scientifically contested. Published research is inconclusive on the question whether school shooters represent a risk group with a special susceptibility to negative effects of violent media content, but empirical findings supply clear indications that reporting of school shootings, especially in the mass media and the internet, can disseminate scripts potentially connected with copycat acts. The concept of cultural scripts of hegemonic masculinity explains why school shootings are committed predominantly by young males and accounts for the importance of a prior interest in violent media content and school shootings. Given the public communicative dimension of these acts and the enormous media attention they attract, there is a case for critical consideration of the way they are treated in the media.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Other scholars arrive at diverging totals, depending on the investigated period and the definition used, but these remain within the same order of magnitude. For example, Robertz and Wickenhäuser (2010, p. 13f.) tally 124 school shootings up to January 1, 2010.

- 2.

Some authors assert that more than one thousand studies have been published (including American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2002; Muscari, 2002). According to Savage and Yancey (2008), these estimates are grossly overstated. However, the 431 studies Bushman and Huesmann (2006) found for their meta-analysis are still a respectable number.

- 3.

Ferguson (2007) identifies the same problem in the violent games literature.

- 4.

For example, various meta-analyses demonstrate that media violence has a greater impact on children, especially younger children, than on adolescents or adults (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001; Paik & Comstock, 1994); Bushman and Huesmann (2006) later refine this finding to show that short-term effects of media violence are greater for adults but the long-term effects greater for children. However, there are no valid findings on the childhood media behavior of school shooters, so it is impossible to tell whether they represent a risk group in this category.

- 5.

In suicide research, the phenomenon of imitation following media reports of suicides is known as the “Werther effect” after Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, which is said to have triggered numerous imitation suicides and was for that reason banned for a time in certain European countries (Gould, Jamieson, & Romer, 2003, p. 1270). As early as the 1970s and 1980s, Phillips demonstrated that newspaper and television reports about suicides were followed by an increase in suicide rates (Bollen & Phillips, 1981, 1982; Phillips, 1974, 1979; Phillips & Carstensen, 1986, 1988). Numerous subsequent studies also demonstrate this effect outside the United States (Sonneck et al. 1994; Jonas, 1992; Sonneck, Etzersdorfer, & Nagel-Kuess, 1994; Stack, 1996). Various studies also report an imitation effect of fictional suicides (Gould, Shaffer, & Kleinman, 1988; Hawton et al., 1999; Schmidtke & Hafner, 1988). This is variously described as a suggestion, contagion, or disinhibition effect.

- 6.

Muschert’s media analysis (2007) shows that just two weeks after the Columbine shooting the media had already lost interest.

References

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. (2002). Media violence harms children. In J. D. Torr (Ed.), Is media violence a problem? (pp. 10–12). New York: Springer.

Anderson, C. (2004). An update on the effects of playing violent video games. Journal of Adolescence, 27(1), 113–122.

Anderson, C., & Dill, K. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 772–790.

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, psychological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12, 353–359.

Anderson, C. A., Carnagey, N. L., & Eubanks, J. (2003). Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 960–971.

Anderson, C. A., Shibuya, A., Ihori, N., Swing, E. L., Bushman, B. J., Sakamoto, A., et al. (2010). Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 151–173.

Baier, D., Pfeiffer, C., Simonson, J., & Rabold, S. (2010). Kinder und Jugendliche in Deutschland: Gewalterfahrungen, Integration, Medienkonsum: Zweiter Bericht zum gemeinsamen Forschungsprojekt des Bundesministeriums des Innern und des KFN (KFN-Forschungsbericht 109). Hannover: KFN.

Baier, D., Pfeiffer, C., Windzio, M., & Rabold, S. (2006). Schülerbefragung 2005: Gewalterfahrungen, Schulabsentismus und Medienkonsum von Kindern und Jugendlichen: Abschlussbericht über eine repräsentative Befragung von Schülerinnen und Schülern der 4. und 9. Jahrgangsstufe. Hannover: Kriminologisches Forschungsinstitut Niedersachsen.

Bannenberg, B. (2010). Amok: Ursachen erkennen—Warnsignale verstehen—Katastrophen verhindern. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus.

Benson, L. (2005, March 24). Web postings hold clues to Weise’s actions. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved May 4, 2012, from http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/2005/03/24_ap_moreweise/.

Böckler, N. (2012). Mediale Selbstdarstellungen jugendlicher Amokläufer. Paper presented at the conference on Mörderische Phantasien—Mediale Selbstdarstellung jugendlicher Amokläufer, Akademie für politische Bildung Tutzing, Bayreuth, Germany, April 21, 2012.

Böckler, N., & Seeger, T. (2010). Schulamokläufer: Eine Analyse medialer Täter-Eigendarstellungen und deren Aneignung durch jugendliche Rezipienten. Weinheim & Munich: Juventa.

Böckler, N., Seeger, T., & Heitmeyer, W. (2010). School shooting: A double loss of control. In W. Heitmeyer, H.-G. Haupt, S. Malthaner, & A. Kirschner (Eds.), Control of violence (pp. 261–294). New York: Springer.

Böckler, N., Seeger, T., & Sitzer, P. (2012). Media dynamics in school shootings: A socialization theory perspective. In G. W. Muschert & J. Sumiala (Eds.), School shootings: Mediatized violence in a global age. Bingley: Emerald.

Bofinger, J. (2001). Kinder—Freizeit—Medien: Eine empirische Untersuchung zum Freizeit- und Medienverhalten 10- bis 17-jähriger Schülerinnen und Schüler. Munich: Kopaed.

Bollen, K. A., & Phillips, D. P. (1981). Suicidal motor vehicle fatalities in Detroit: a replication. American Journal of Sociology, 87, 404–412.

Bollen, K. A., & Phillips, D. P. (1982). Imitative suicides: a national study of effects of television news stories. American Sociological Review, 47, 802–809.

Bortz, J., & Döring, N. (2006). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation: für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler. Berlin: Springer.

Borum, R., Cornell, D. G., Modzeleski, W., & Jimersonet, S. R. (2010). What can be done about school shootings? A review of the evidence. Educational Researcher, 39(1), 27–37.

Boxer, P., Huesmann, L. R., Bushman, B. J., O’Brien, M., & Moceri, D. (2008). The role of violent media preference in cumulative developmental risk for violence and general aggression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(3), 417–428.

Browne, K., & Pennell, A. (1998). The effects of video violence on young offenders. London: Home Office Research Development and Statistics Directorate. Research findings, No. 65, pp. 1–4.

Bushman, B., & Anderson, C. A. (2002). Violent video games and hostile expectations: A test of the generalized aggression model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1679–1686.

Bushman, B. J. (1995). Moderating role of trait aggressiveness in the effects of violent media on aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 950–960.

Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Media violence and the American public: Scientific facts versus media misinformation. American Psychologist, 56(6/7), 477–489.

Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223–254). London: Sage.

Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2006). Short-term and long-term effects of violent media on aggression in children and adults. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160, 348–352.

Coleman, L. (2004). The copycat effect: How the media and popular culture trigger the mayham in tomorrow’s headlines. New York: Paraview.

Colwell, J., & Kato, M. (2003). Investigation of the relationship between social isolation, self-esteem, aggression and computer game play in Japanese adolescents. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 6, 149–158.

Connell, R.W. (1993): The Big Picture: Masculinities in Recent World History. In: Theory and Society, 22, 597–623.

Connell, R. (2005). Masculinities (Vol. 1). Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Cullen, D. (1999, September 30). Who said “yes?” Salon.com. Retrieved May 4, 2012, from http://www.salon.com/1999/09/30/bernall/.

Deutscher Presserat. (2010). Berichterstattung über Amokläufe: Empfehlungen für Redaktionen. Berlin: Deutscher Presserat. Retrieved March 6, 2012, from http://www.presserat.info/fileadmin/download/PDF/Leitfaden_Amokberichterstattung.pdf.

Engels, H. (2007). Das School Shooting von Emsdetten—der letzte Ausweg aus dem Tunnel!? Eine Betrachtung aus Sicht des Leiters der kriminalpolizeilichen Ermittlungen. In J. Hoffmann & I. Wondrak (Eds.), Amok und zielgerichtete Gewalt an Schulen: Früherkennung/Risikomanagement/Kriseneinsatz/Nachbetreuung (pp. 35–56). Frankfurt: Polizeiwissenschaft.

Expertenkreis Amok. (2009). Prävention, Intervention, Opferhilfe, Medien: Konsequenzen aus dem Amoklauf in Winnenden und Wendlingen am 11. März 2009. Baden-Württemberg: Expertenkreis Amok.

Fast, J. (2008). Ceremonial violence: A psychological explanation of school shootings. New York: Overlook.

Feasey, R. (2008). Masculinity and popular television. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ferguson, C. J. (2007). Evidence for publication bias in video game violence effects literature: A meta-analytic review. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 12, 470–482.

Ferguson, C. J., & Kilburn, J. (2009). The public health risks of media violence: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Pediatrics, 154(5), 759–763.

Ferguson, C. J., Rueda, S. M., Cruz, A. M., Ferguson, D. E., Fritz, S., & Smith, S. M. (2008). Violent video games and aggression. Causal relationship or byproduct of family violence and intrinsic violence motivation? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(3), 311–332.

Ferguson, C. J., San Miguel, C., Garza, A., & Jerabeck, J. M. (2012). A longitudinal test of video game violence influences on dating and aggression: A 3-year longitudinal study of adolescents. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(2), 141–146.

Ferguson, C. J., San Miguel, C., & Hartley, R. D. (2009). A multivariate analysis of youth violence and aggression: The influence of family, peers, depression, and media violence. The Journal of Pediatrics, 155(6), 904–908.

Funk, J. B. (2003). Violent video games: Who’s at risk?’. In D. Ravitch & J. P. Viteritti (Eds.), Kid stuff: Marketing sex and violence to America’s children (pp. 168–192). Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Gibbs, N., & Roche, T. (1999, December 12). The Columbine tapes. Time. Retrieved April 26, 2012, from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,35870,00.html.

Giumetti, G. W., & Markey, P. M. (2007). Violent video games and anger as predictors of aggression. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(6), 1234–1243.

Gould, M., Jamieson, P., & Romer, D. (2003). Media contagion and suicide among the young. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(9), 1269–1284.

Gould, M. S., Shaffer, D., & Kleinman, M. (1988). The impact of suicide in television movies: Replication and commentary. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 18, 90–99.

Grimm, J. (1999). Fernsehgewalt: Zuwendungsattraktivität, Erregungsverläufe, sozialer Effekt: Zur Begründung und praktischen Anwendung eines kognitiv-physiologischen Ansatzes der Medienrezeptionsforschung am Beispiel von Gewaltdarstellungen. Opladen & Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Grimm, J. (2002). Wirkungsforschung II: Differentiale der Mediengewalt—Ansätze zur Überwindung der Individualisierungs- und Globalisierungsfalle innerhalb der Wirkungsforschung. In T. Hausmanninger & T. Bohrmann (Eds.), Mediale Gewalt: Interdisziplinäre und ethische Perspektiven (pp. 160–176). Munich: Fink.

Harding, D. J., Fox, C., & Mehta, J. D. (2002). Studying rare events through qualitative case studies: Lessons from a study of rampage school shootings. Sociological Methods & Research, 31(2), 174–217.

Hawton, K., Simkin, S., Deeks, J. J., O’Connor, S., Keen, A., Altman, D. G., et al. (1999). Effects of a drug overdose in a television drama on presentations to hospital for self-poisoning: Time series and questionnaire study. British Medical Journal, 318, 972–977.

Hearold, S. (1986). A synthesis of 1043 effects of television on social behavior. In G. Comstock (Ed.), Public communication and behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 65–133). New York: Academic.

Hoffmann, J. (2007). Tödliche Verzweiflung—der Weg zu zielgerichteten Gewalttaten an Schulen. In J. Hoffmann & I. Wondrak (Eds.), Amok und zielgerichtete Gewalt an Schulen: Früherkennung/Risikomanagement/Kriseneinsatz/Nachbetreuung (pp. 25–34). Frankfurt: Polizeiwissenschaft.

Hogben, M. (1998). Factors moderating the effect of television aggression on viewer behavior. Communication Research, 25, 220–247.

Hopf, W. H. (2004). Mediengewalt, Lebenswelt und Persönlichkeit—eine Problemgruppenanalyse bei Jugendlichen. Zeitschrift für Medienpsychologie, 16(3), 99–115.

Hopf, W. H., Huber, G. L., & Weiß, R. H. (2008). Media violence and youth violence: A 2-year longitudinal study. Journal of Media Psychology, 20(3), 79–96.

Huesmann, L. R. (2007). The impact of electronic media violence: Scientific theory and research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S6–S13.

Huesmann, L. R., Moise-Titus, J., Podolski, C. L., & Eron, L. D. (2003). Longitudinal relations between children’s exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977–1992. Developmental Psychology, 39, 201–221.

Ich will R.A.C.H.E. (2006, November 21). Telepolis. Retrieved September 28, 2012, from http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/24/24032/1.html.

Irwin, A. R., & Gross, A. M. (1995). Cognitive tempo, violent video games, and aggressive behavior in young boys. Journal of Family Violence, 10, 337–350.

Johnson, D. J., Cohen, P., Smailes, E. M., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. S. (2002). Television viewing and aggressive behavior during adolescence and adulthood. Science, 295, 2468–2471.

Jonas, K. (1992). Modeling and suicide: A test of the Werther effect. British Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 295–306.

Josephson, W. L. (1987). Television violence and children’s aggression: Testing the priming, social script, and disinhibition predictions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 882–890.

Kalish, R., & Kimmel, M. (2010). Suicide by mass murder: Masculinity, aggrieved entitlement, and rampage school shootings. Health Sociology Review, 19(4), 451–464.

Katz, J., & Jhally, S. (1999, May 2). The national conversation in the wake of Littleton is missing the mark. The Boston Globe, E1.

Kidd, S. T., & Meyer, C. L. (2002). Similarities of school shootings in rural and small communities. Journal of Rural Community Psychology, E5(1). Retrieved March 6, 2012, from http://www.marshall.edu/jrcp/sp2002/similarities_of_school_shootings.htm.

Kimmel, M. S., & Mahler, M. (2003). Adolescent masculinity, homophobia, and violence. American Behavioral Scientist, 46(10), 1439–1458.

Kostinsky, S., Bixler, E. O., & Kettl, P. A. (2001). Threats of school violence in Pennsylvania after media coverage of the Columbine high school massacre: Examining the role of imitation. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 155, 994–1001.

Kristen, A., Oppel, C., & von Salisch, M. (2007). Computerspiele mit und ohne Gewalt: Auswahl und Wirkung bei Kindern. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Kunczik, M., & Zipfel, A. (2006). Gewalt und Medien: Ein Studienhandbuch. Cologne, Weimar, & Vienna: Böhlau.

Larkin, R. W. (2007). Comprehending Columbine. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Larkin, R. W. (2009a). The Columbine legacy: Rampage shootings as political acts. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(9), 1309–1326.

Larkin, R. W. (2010). Masculinity, school shooters, and the control of violence. In W. Heitmeyer, H.-G. Haupt, S. Malthaner, & A. Kirschner (Eds.), Control of violence (pp. 315–344). New York: Springer.

Leary, M. R., Kowalski, R. M., Smith, L., & Phillips, S. (2003). Teasing, rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 202–214.

Lehnberger, G. (2009). Abschließender Pressebericht i. S. Amoklauf Ansbach – neue Erkenntnisse über Tathergang und Tatmotiv. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from http://www.justiz.bayern.de/sta/sta/an/presse/archiv/2009/02227/.

Maguire, B., Weatherby, G. A., & Mathers, R. A. (2002). Network news coverage of school shootings. The Social Science Journal, 39, 465–470.

McGee, J. P., & DeBernardo, C. R. (1999). The classroom avenger. The Forensic Examiner, 8, 1–16.

Meloy, J. R., Hempel, A. G., Mohandie, K., Shiva, A. A., & Gray, B. T. (2001). Offender and offense characteristics of a nonrandom sample of adolescent mass murderers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(6), 719–728.

Melzer, W., & Rostampour, P. (1998). Prädiktoren schulischer Gewalt im außerschulischen Bereich. In Arbeitsgruppe Schulevaluation (Eds.), Gewalt als soziales Problem in Schulen. Untersuchungsergebnis und Praäventionsstrategien (pp. 149–188). Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

Messner, S. (1986). Television violence and violent crime: An aggregate analysis. Social Problems, 33, 218–235.

Ministry of Justice. (2009). Jokela School Shooting on 7 November 2007: Report of the Investigation Commission. Helsinki: Ministry of Justice.

Modzeleski, W., Feucht, T., Hall, J. E., Simon, T. R., Butler, L., Taylor, A., et al. (2008). School-associated student homicides—United States, 1992–2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57(2), 33–36.

Möller, I. (2011). Gewaltmedienkonsum und Aggression. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 2011(3), 921 18–23.

Möller, I., & Krahé, B. (2009). Exposure to violent video games and aggression in German adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 35(1), 75–89.

Moore, M. H., Petrie, C. V., Braga, A. A., & McLaughlin, B. L. (Eds.). (2003). Deadly lessons: Understanding lethal school violence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Mößle, T., Kleimann, M., & Rehbein, F. (2007). Bildschirmmedien im Alltag von Kindern und Jugendlichen. Nomos: Baden-Baden.

Muscari, M. (2002). Media violence: Advice for parents. Pediatric Nursing, 28(6), 585–591.

Muschert, G. W. (2007). The Columbine victims and the myth of the juvenile superpredator. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 5(4), 351–366.

Muschert, G. W., & Carr, D. (2006). Media salience and frame changing across events: Coverage of nine school shootings 1997–2001. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(4), 747–766.

Muschert, G. W., & Larkin, R. W. (2007). The Columbine high school shootings. In S. Chermak & F. Y. Bailey (Eds.), Crimes & trials of the century (pp. 253–266). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Muschert, G. W., & Ragnedda, M. (2010). Media and control of violence: Communication in school shootings. In W. Heitmeyer, H.-G. Haupt, S. Malthaner, & A. Kirschner (Eds.), Control of violence (pp. 345–361). New York: Springer.

National Institute of Mental Health. (1982). Television and behavior: Ten years of scientific progress and implications for the eighties: Vol. 1. Summary report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Neroni, H. (2000). The men of Columbine: Violence and masculinity in American culture and film. Journal for the Psychoanalysis of Culture and Society, 5(2), 256–263.

Newman, K. S., Fox, C., Harding, D. J., Mehta, J., & Roth, W. (2004). Rampage: The social roots of school shootings. New York: Basic.

Nolting, H.-P. (2004). Lernfall Aggression: Wie sie entsteht—wie sie zu verhindern ist. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

O’Toole, M. E. (1999). The school shooter: A threat assessment perspective. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Ogle, J. P., Eckman, M., & Leslie, C. A. (2003). Appearance cues and the shootings at Columbine High: Construction of a social problem in the print media. Sociological Inquiry, 73(1), 1–27.

Oliver, M. B. (2000). The respondent gender gap. In D. Zillmann & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Media entertainment (pp. 215–234). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Paik, H., & Comstock, G. (1994). The effects of television violence on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Communication Research, 21, 516–539.

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (1999). Columbine shooting biggest news draw of 1999. Retrieved March 2, 2012, from http://www.people-press.org/1999/12/28/columbine-shooting-biggest-news-draw-of-1999.

Phillips, D. (1974). The influence of suggestion on suicide: Substantive and theoretical implications of the Werther effect. American Sociological Review, 39, 340–354.

Phillips, D. (1979). Suicide, motor vehicle fatalities, and the mass media: Evidence toward a theory of suggestion. The American Journal of Sociology, 84, 1150–1174.

Phillips, D., & Carstensen, L. L. (1986). Clustering of teenage suicides after television news stories about suicide. The New England Journal of Medicine, 315, 685–689.

Phillips, D. P., & Carstensen, L. L. (1988). The effect of suicide stories on various demographic groups, 1968–1985. In R. Maris (Ed.), Understanding and preventing suicide: Plenary papers of the first combined meeting of the AAS and IASP (pp. 100–114). New York: Guilford.

Robertz, F. J. (2004). School Shootings: Über die Relevanz der Phantasie für die Begehung von Mehrfachtötungen durch Jugendliche. Frankfurt: Polizeiwissenschaft.

Robertz, F. J. (2007). Nachahmung von Amoklagen: Über Mitläufer, Machtphantasien und Medienverantwortung. In J. Hoffmann & I. Wondrak (Eds.), Amok und Zielgerichtete Gewalt an Schulen: Früherkennung/Risikomanagement/Kriseneinsatz/Nachbetreuung (pp. 71–85). Polizeiwissenschaft: Frankfurt am Main.

Robertz, F. J., & Wickenhäuser, R. (2010). Der Riss in der Tafel: Amoklauf und schwere Gewalt in der Schule (2nd ed.). Berlin: Springer.

Robinson, T. N. (2003). The effects of cutting back on media exposure. In D. Ravitch & J. P. Viteritti (Eds.), Kid stuff: Marketing sex and violence to America’s children (pp. 193–213). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Robinson, T. N., Wilde, M. L., Navracruz, L. C., Haydel, K. F., & Varady, A. (2001). Effects of reducing children’s television and video game use on aggressive behavior. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 155, 17–23.

Savage, J. (2004). Does viewing violent media really cause criminal violence? A methodological review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10, 99–128.

Savage, J., & Yancey, C. (2008). The effects of media violence exposure on criminal aggression: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35, 772–791.

Scheithauer, H., & Bondü, R. (2011). Amokläufe und School Shootings. Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht.

Schmidtke, A., & Hafner, H. (1988). The Werther effect after television films: New evidence for an old hypothesis. Psychological Medicine, 18, 665–676.

Schmidtke, A., Schaller, S., Stack, S., Lester, D., & Müller, I. (2005). Imitation of amok and amok-suicide. In J. McIntosh (Ed.), Suicide 2002: Proceedings of the 35th annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology (pp. 205–209). Washington, DC: American Association of Suicidology.

Sherry, J. (2001). The effects of violent video games on aggression: A meta-analysis. Human Communication Research, 27, 409–431.

Slater, M. D., Henry, K. L., Swaim, R. C., & Anderson, L. L. (2003). Violent media content and aggressiveness in adolescents: A downward spiral model. Communication Research, 30(6), 713–736.

Sonneck, G., Etzersdorfer, E., & Nagel-Kuess, S. (1994). Imitative suicide on the Viennese subway. Social Science & Medicine, 38, 453–457.

Stack S (1996). The effect of the media on suicide: evidence from Japan. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 26, 405–414.

Steiner, O. (2009). Neue Medien und Gewalt: Expertenbericht 04/09 (Beiträge zur sozialen Sicherheit). Bern: Bundesamt für Sozialversicherungen.

Surgeon General’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Television and Social Behavior. (1972). Television and growing up: The impact of televised violence. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Trudewind, C., & Steckel, R. (2002). Unmittelbare und langfristige Auswirkungen des Umgangs mit gewalthaltigen Computerspielen: Vermittelnde Mechanismen und Moderatorvariablen. Polizei und Wissenschaft, 1, 83–100.

Unsworth, G., Devilly, G., & Ward, T. (2007). The effect of playing violent video games on adolescents: Should parents be quaking in their boots? Psychology, Crime and Law, 13, 383–394.

Vandewater, E. A., Lee, J. H., & Shim, M. S. (2005). Family conflict and violent electronic media use in school-aged children. Media Psychology, 7(1), 73–86.

Verlinden, S., Hersen, M., & Thomas, J. (2000). Risk factors in school shootings. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 3–56.

Vossekuil, B., Fein, R., Reddy, M., Borum, R., & Modzeleski, W. (2002). The final report and findings of the Safe School Initiative: Implications for the prevention of school attacks in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Secret Service & U.S. Department of Education.

Wallenius, M., Punamaki, R.-L., & Rimpela, A. (2007). Digital game playing and direct and indirect aggression in early adolescence: The roles of age, social intelligence, and parent–child communication. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 325–336.

Watson, J. (2002). The martyrs of Columbine: Faith and the politics of tragedy. New York: Palgrave.

Wilgoren, J. (2005, 22 March). Shooting rampage by student leaves 10 dead on reservation. The New York Times, p. A1.

Wood, W., Wong, F. Y., & Chachere, J. G. (1991). Effects of media violence on viewers’ aggression in unconstrained social interaction. Psychological Bulletin, 109, 371–383.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sitzer, P. (2013). The Role of Media Content in the Genesis of School Shootings: The Contemporary Discussion. In: Böckler, N., Seeger, T., Sitzer, P., Heitmeyer, W. (eds) School Shootings. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5526-4_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5526-4_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-5525-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-5526-4

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)