Abstract

Since the financial crisis, various policy initiatives have been adopted in the UK with a view to improve access to finance for SME businesses. One of these initiatives is the bank referral scheme. Under this scheme, incumbent banks must pass on information about SMEs (with an SME’s consent) that were unsuccessful in securing bank funding, to so-called finance platforms whose role is to match SMEs with alternative lenders. The scheme received attention in the UK and elsewhere as an innovative way to combine information sharing and technology in order to help SMEs gain access to external finance. It was launched in 2016. Since then, it has been closely monitored by the UK Treasury. The aim of this article is to reflect on the bank referral scheme and its raison d’être, especially by focussing on the regulations which implement the scheme, and on potential ways to improve the referral process.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Since the financial crisis, various policy initiatives have been adopted in the UK with a view to improve access to finance for small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) businesses. One of these initiatives is the bank referral scheme. Under this scheme, incumbent banks, which have dominated the SME funding market in the UK, must share (with an SME’s consent) information about an SME that seeks external funding with so-called ‘finance platforms’. The scheme was designed to help SMEs, which fail to secure funding with incumbent banks, to find alternative sources of funding. An important aspect of the scheme is the reliance on information sharing and online platforms (finance platforms) to match SMEs with a diverse range of alternative finance providers. Three finance platforms were designated by the UK Treasury and entrusted with the role of receiving SME details (so-called designated information) from incumbent banks (so-called designated banks).

The scheme was launched in November 2016 as a flagship initiative of the Treasury for the benefit of SMEs. It received a fair amount of attention in the UK and elsewhere,Footnote 1 including at EU level in the context of the Commission’s Capital Markets Union initiative.Footnote 2 A first review of the scheme was commissioned by the UK Treasury in 2017, less than a year after the scheme was launched. There was significant interest in the findings of the review. However, the data made disappointing reading for many observers.Footnote 3 Moreover, the Treasury decided to withhold several findings including the number of bank referrals, and the recommendations that followed the review, despite several freedom of information requests including one by this author.Footnote 4 A second review took place a year later in August 2018.Footnote 5 The figures regarding the scheme’s performance that the Treasury released were encouraging even though still modest. The data shows that since the launch of the scheme, 902 businesses raised over £15 million in funding by using finance platforms. For the first time, the data also showed the actual number of referrals by banks. However, the Treasury continues to keep a tight grip on the release of information. Few explanations were given with respect to the figures and the Treasury did not disclose some key figures, especially the number of rejections of SME finance applications by banks relative to the number of referrals offered by those banks—a key indicator of how diligently designated banks comply with their new referral duties.

The aim of this article is to reflect on the bank referral scheme, its raison d’être and its workings. The bank referral scheme was essentially designed as a sort of ‘clearing’Footnote 6 scheme for unfunded, but not unfundable SME businesses. Specifically the aim of the scheme is to help clear the SME funding market of businesses that need external funding, but that—even though fundable—were unsuccessful with incumbent banks. As pointed out, in case where an SME business unsuccessfully applies for finance with a designated bank, the latter must (with an SME’s consent) share information about the business’ funding needs with finance platforms whose role is to act as a gateway to alternative lenders. Thus, a key consideration underpinning the scheme is that SMEs do not have perfect information about the range of alternative sources of funding. The proposition of finance platforms is that technology can provide an effective means to find the best match between those lenders and SMEs.

To be sure, of those SMEs whose details are referred to finance platforms, many will not be fundable. However, the premise is that among those SMEs that are released into ‘clearing’ following an unsuccessful funding application with an incumbent bank, there will be businesses that are fundable by alternative lenders, for example, because the latter have different lending appetites or because they are better suited to deal with certain risks.Footnote 7

Although the bank referral scheme has received attention by policy-makers, the alternative finance industry and the SME sector, very little has been said about the scheme in academia.Footnote 8 This article seeks to contribute to filling this gap. Prima facie, there are various areas that are worthy of investigation: the role of finance platforms at the interface between SMEs and alternative lenders, the role of technology in facilitating matchmaking, etc. This article focusses mainly on the referral process and the regulations that implement the referral duties of banks. Whilst the bank referral scheme seeks to make effective use of technology in order to help SMEs to find funding, the regulations are firmly grounded in an ‘analogue’ world, setting out processes that potentially risk being protracted or that leave room for participants to stifle the referral process. This article will therefore seek to shine a critical light on the regulations that implement the bank referral scheme and reflect on ways in which the referral process could potentially be improved. It discusses a number of possible options, including reconsidering the moment at which certain duties arise under the scheme—an option which this article terms ‘frontloading’—or giving greater consideration to the spirit of the scheme in the regulations by using open textured principles.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 focusses on the SME funding market and the issues—especially the information failures—that have arisen in this market. Section 3 examines the workings of the bank referral scheme by focusing on the role of information sharing and finance platforms. Section 4 takes a critical look at the bank referral scheme, its raison d’être and the referral process. In this process, it also reflects on ways in which the referral process could be improved. Finally, Sect. 5 summarizes findings and concludes on the theme of ‘undisruption’.

2 SME Funding and Informational Failures

The aim of this section is to discuss issues that have arisen in the SME funding market and that have made it more difficult for SMEs to gain access to a wider range of funding options.Footnote 9 Historically, SMEs have been heavily dependent on bank funding. This has been the case in the UK, but also elsewhere in the EU.Footnote 10 There are a number of well documented reasons for this. They have to do with the relatively modest amount of external finance that SMEs typically require and that makes it uneconomical for many SMEs to rely on certain expensive sources of funding, e.g. capital markets which require compliance with extensive disclosure obligations. They have also to do with information asymmetries that are said to abound in the SME funding market. Traditionally, finance providers other than an SME’s main bank have been at a disadvantage when attempting to gain a sufficiently accurate and comprehensive view of the creditworthiness of an SME business. This is because they typically have inadequate access to information (or information of sufficient quality) about an SME’s financial situation, its credit history, its repayment capacity or payment performance.Footnote 11 Banks on the other hand have often been in a better position to deal with information asymmetries because of their ongoing relationships with SME customers and because of the information that is produced as part of this. For example, as providers of business current accounts, banks are in a position to gain very useful information on the payment performance of an SME customer. In the UK, the advantage of having access to current account data for assessing the creditworthiness of SMEs was highlighted in a number of reports, including in the retail banking market investigation report of the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). It noted:

Considering that an SME’s [business current account (BCA)] bank holds more information on its financial performance, the BCA bank is in a position to better assess the risk, more accurately price credit, and potentially make a lending decision more quickly than other finance providers. While of benefit to the SME, this would also suggest that the informational advantages that the BCA bank holds over other potential lenders is a real barrier to searching for credit, rather than simply a perception of SMEs.Footnote 12

However, information failures have not only affected alternative finance providers. SMEs have also faced information barriers when considering how to grow their business, to acquire working capital, to manage cash flows, etc. SMEs are neither owned nor managed by omnipotent beings with perfect information and infinite computational capabilities.Footnote 13 At the risk of generalising, SMEs face a number of obstacles when considering external sources of finance.Footnote 14 They may lack information about alternative sources of finance. They are often unwilling or unable to invest time and effort in securing finance.Footnote 15 Micro- or small businesses might not be sufficiently educated on the advantages or disadvantages of alternative sources of finance or lack confidence in dealing with alternative finance providers.Footnote 16 Moreover, even if they show awareness of alternative sources of finance, they might still be unable to differentiate between trustworthy or untrustworthy providers. The existence of information failures on the funding demand side has been widely acknowledged in reports in the UK and elsewhere. For example, according to the British Business Bank (BBB), a government owned development bank which seeks to improve the funding prospects of small businesses,

[…] most UK SMEs are not aware of financial products beyond standard term bank loans, overdrafts and credit cards. And, even where they are aware of a product, often they may not practically know a trusted provider of that product to contact.Footnote 17

These behavioural traits are also said to benefit incumbent banks. The latter have an infrastructure (a network of branches) that makes it easier to reach SMEs. They also benefit from their ongoing relationship with SME customers. Unsurprisingly, an SME’s main bank typically remains the first port of call for SMEs which seek external finance (in the form of loans, overdraft facilities, credit cards, etc.).Footnote 18

3 The Workings of the Bank Referral Scheme

This section discusses key aspects of the bank referral scheme, especially its reliance on information sharing as a means to deal with information barriers affecting SMEs (Sect. 3.1) and on finance platforms to enable matchmaking between SMEs and alternative lenders (Sect. 3.2).

3.1 Bank Referrals and Information Sharing

The bank referral scheme was an attempt by the UK government to deal with information barriers affecting SMEs on the funding demand side. The origins of the scheme can be traced back to the UK government’s 2014 budget in which the government announced that it would consult on whether to initiate legislative action in order to help SMEs, which had failed to secure funding, to find alternative sources of finance.Footnote 19 The bank referral scheme was subsequently adopted in section 5 of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 (SBEE Act) and implemented in the Small and Medium Sized Business (Finance Platforms) Regulations 2015 (hereinafter, the ‘Finance Platform Regulations’ or simply the regulations). The thrust of the scheme is simple: to require an incumbent bank to share information about an SME, which seeks external funding, with so-called finance platforms in case where an SME business failed to secure funding with the bank. By incumbent banks I mean so-called designated banks. Not all banks are subject to information sharing duties under the bank referral scheme. Those that must participate in the scheme are designated by the UK Treasury, which also holds the power to revoke their designation.Footnote 20 The criteria for designation are set out in the Finance Platform Regulations which provide that when considering whether to designate a bank (or revoke its designation), the Treasury must have regard to the value of lending by the bank to SMEs; the proportion of such lending relative to the total value of lending to SMEs; and the importance to the economy in Northern Ireland of the bank’s lending to SMEs.Footnote 21 The Finance Platform Regulations add that the Treasury has also the discretionary power to have regard to other matters that it considers appropriate.Footnote 22 So far the Treasury has designated nine banksFootnote 23 which include those that account for the vast majority of SME lending in the UK and which make for a concentrated SME funding market where, according to the CMA, competition for SME lending is not working well.Footnote 24

That said, information sharing has three key features under the bank referral scheme. First, information sharing is mandatory: provided that an SME customer consents, a designated bank must share the relevant information with finance platforms. The fact that banks were mandated to share information is because voluntary initiatives by the banking sector were seen as having failed to work well enough. They were seen as ‘slow in achieving results’,Footnote 25 which ultimately strengthened the case for legislative action.

To be sure, it is always open to an SME to ‘self-refer’, that is to share itself its information with finance platforms. Indeed, the Finance Platform Regulations foresee that a bank must provide an SME with generic information about finance platforms in case where an SME does not consent to its information being shared with finance platforms by the bank.Footnote 26 The added value of a bank referral boils down to a couple of propositions: firstly, from an SME’s point of view, it helps it on its journey to find external finance by taking the search for alternative sources of funding out of an SME’s hands at the point of rejection of a finance application by its bank; secondly, from an alternative lender’s perspective which lacks visibility in the SME funding market, it greatly facilitates access to SMEs that have external funding needs. Moreover, the fact that banks are involved and that finance platforms are specifically designated by the UK Treasury is likely to improve the credibility of the scheme in the eyes of SMEs.

Secondly, the information that is shared with finance platform is very basic (raw) information about an SME and the funding that it seeks. Specifically, the information (known as ‘designated information’) concerns the contact details of an SME customer; the amount and type of finance that it seeks; the legal structure of the SME business; the duration for which the SME has been trading and receiving income; and the date by which finance is required or, if unknown, the date by which the SME has requested finance.Footnote 27

Since the information that is shared is very basic, it will not allow alternative funders to make funding decisions. Hence, the third feature of the information that is shared is that it is insufficient. As pointed out, alternative lenders will, inter alia, require information about the creditworthiness of an SME in order to make funding decisions. The referral scheme is not designed to deal with information failures affecting the funding supply side and which make it difficult for alternative lenders to distinguish between high risk and low risk SME businesses. However, there are various other initiatives that seek to deal with such failures and issues of adverse selection.Footnote 28 One of them was introduced in parallel to the bank referral scheme: the commercial credit data sharing scheme. Section 4 of the SBEE Act requires the sharing of SME credit information with designated credit reference agencies.Footnote 29 Under this scheme, the latter will receive such information from designated banks and will, provided certain conditions are met, be required to pass on this information to finance providers.Footnote 30 To be sure, credit information was already shared previously via credit reference agencies in the UK. However, the UK legislature took the view that access to relevant information was still too restricted and that legislative action was required in order to level the playing field.Footnote 31

Besides the commercial credit data scheme, there are other initiatives that might come to facilitate the lending decisions of alternative finance providers. The UK open banking initiative is arguably the most significant initiative on information sharing in the banking sector. Backed by the UK CMA,Footnote 32 the aim of open banking is to improve competition and innovation in the UK retail banking market by making it easier for bank customers, including SME customers, to (inter alia) share account information with third party providers.Footnote 33 Open banking in the UK builds on API technology. APIs or application programming interfaces are standards which make it possible for software systems to interact with each other and to share data.Footnote 34 The expectation is that by using API technology, open banking will enable the development of a whole range of new services and by allowing access to online account information (subject to the consent of a bank customer) to, inter alia, allow lenders to make more informed lending decisions.

The EU too is seeking to facilitate greater information sharing.Footnote 35 However, the EU has stayed clear of a mandatory bank referral scheme for SMEs. Although the Commission has expressed concerns over information failures in the SME funding market and has been an advocate of greater financial diversification for SMEs in its Capital Markets Union (CMU) initiative, it did not endorse a mandatory referral scheme or other intrusive action on information sharing by banks. It also stayed clear of advocating actions on credit information sharing in relation to SMEs in its recent action plan on Fintechs which is part of the Commission’s work on a CMU and a Digital Single Market.Footnote 36 The Commission appears largely to have endorsed the position of the banking sector which considered that existing initiatives under the PSD2 or the GDPR were sufficient.Footnote 37 All in all, the Commission has preferred less intrusive actions in the context of its CMU initiative. It has encouraged the banking sector to give better feedback to SMEs which have had their application for funding declined.Footnote 38 It also launched a Horizon 2020 call to fund projects on improving access by SMEs to alternative forms of finance.Footnote 39

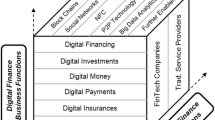

3.2 Finance Platforms

Besides information sharing, another key feature of the bank referral scheme is its reliance on so-called ‘finance platforms’. Finance platforms are there to act as matchmakers between SMEs, which failed to secure funding with a designated bank, and alternative lenders. They are specifically designated by the UK Treasury, which can also revoke their designation. Thus, it is the role of a government department and not the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), to control access to the ‘finance platform’ denomination and, as such, to the benefits—in terms of the right to receive referrals—that come with this designation. Finance platforms are commercial enterprises. There are currently three platforms that were designated by the Treasury,Footnote 40 after consulting the BBB which periodically invites applications and which is in charge of due diligence on applicants.Footnote 41

While designation is a matter for the Treasury, finance platforms are also independently authorised by the FCA as credit brokers.Footnote 42 Platforms operate as intermediaries. They do not lend off their balance sheets. They operate as online comparison sites which specialise in SME business finance. Finance platforms have therefore also been described as engaging in a form of ‘technology-enabled broking’.Footnote 43 That said, very little is known about the requirements made to this type of technology-enabled broking, including the requirements made to the platforms’ matching algorithms which remain essentially a black box. Whether the matching process is entirely automated is also unclear. It seems likely that for at least a proportion of the referrals that transit the online sites some form of manual interventions will still be necessary during the matching process.

Conceptually, matching platforms can be described as two-sided markets. Rysman describes a two-sided market in general terms as a one where ‘(1) two sets of agents interact through an intermediary or platform, and (2) the decisions of each set of agents affect the outcomes of the other set of agents, typically through an externality’.Footnote 44 The latter could relate to usage or membership of the platform.Footnote 45 Much of the literature on two-sided markets looks at pricing choices made by the intermediary (the platform) given the existence of this externality or interdependence between the two sets of agents.Footnote 46 As far as finance platforms are concerned, the Finance Platform Regulations seek to regulate the basics of the platform’s pricing structure. Regulation 6(7) provides that a finance platform must not charge fees to SMEs to use their matching service.Footnote 47 Finance platforms must hence generate income by charging the other side of the market, i.e., finance providers (lenders).Footnote 48 For example, they might charge them membership fees for adding them to the panel of lenders of the platform. They might also charge them fees based on the successful provision of funding. The Finance Platform Regulations make it clear that compliance with the finance platform’s terms, ‘including the payment of any fees’ is a requirement for finance providers to gain access to information that was referred.Footnote 49 Apart from this, however, the regulations have little to say on issues such as the selection of lenders, the terms and pricing that platforms can impose on finance providers and generally the possible conflict of interests that might arise under the platforms’ business models, as seen in light of the pricing structure of platforms.

That said, since finance platforms are all currently authorised as credit brokers by the FCA, they will have to comply with relevant regulatory requirements that come with this status.Footnote 50 What is more, the Finance Platform Regulations also entrust the FCA with a monitoring and enforcement role,Footnote 51 as well as with authority to issue guidance.Footnote 52 However, the verification work of the nuts and bolts of the platform models was delegated by the Treasury to the BBB (and not the FCA). As pointed out, the BBB carries out due diligence on platform applicants and presumably as part of this process will want to make sure that conflict of interests in the platform model are addressed. However, the extent to which this is the case cannot be ascertained here.

4 Mandatory Referrals: Smart Idea? Smart Regulations?

The previous section discussed the role of information sharing and finance platforms under the bank referral scheme. The aim of this section is to critically reflect on the mandatory referral scheme, especially its raison d’être (Sect. 4.1) as well as the referral process as implemented in the Finance Platform Regulations (Sect. 4.2).

4.1 Smart Idea?

Conceptually, the bank referral scheme can be described as a sort of ‘clearing’ scheme for SME businesses that seek external finance. ‘Clearing’ because the ambition is to help clear the SME funding market of businesses which need external funding, but which (even though fundable) were unsuccessful with incumbent banks. It is to this effect that the scheme combines information sharing duties (to overcome information barriers) and technology (to improve matchmaking). The premise is that among those SMEs that are released into ‘clearing’ via a bank referral, there will be businesses that are fundable by alternative lenders, for example because the latter have different lending appetites or because they are better suited to deal with certain idiosyncratic risks. By entrusting referral duties to designated banks, the scheme also seeks to make the most of the status quo in the SME funding market, especially the lack of shopping for funding among SMEs and the fact that for many SMEs their main bank is their first port of call.

That said, when considering how well the referral scheme can perform its functions, there are inevitably various factors to consider. For one thing, to be effective, it is plain that there has to be a thriving market for SME finance. As far as the bank referral scheme is concerned, this market is limited to debt-based finance. Finance platforms are not a gateway to equity finance.Footnote 53 Still, there is a variety of alternative lenders, ranging from niche lenders to established banks, in the SME funding market and a variety of funding products are available, e.g., various forms of business loans, invoice finance, asset finance, or peer-to-peer business lending which is gaining share especially among smaller businesses in the UK.Footnote 54 Under the Finance Platform Regulations, finance providers (lenders) must join the lending panel of a platform and comply with the terms of the platform in order to be in a position to benefit from the information sharing duties of designated banks.Footnote 55

Other factors will matter too in determining whether the scheme will be a success. It will, for example, depend on how effectively finance platforms and their matching technology can perform their tasks.Footnote 56 Clearly SMEs also have an important role to play in making the scheme a success. SMEs are a very diverse group of businesses and the SME denomination brushes over the very considerable differences that exist between SMEs, e.g., in terms of size, industry and sector, growth ambitions, etc.Footnote 57 Plainly, SMEs must be willing to consider alternative lenders. Moreover, they must be willing to engage with finance platforms. In actual practice, many choose not to.Footnote 58 Moreover, finding the most suitable funding instrument for an SME business presupposes that an SME is sufficiently knowledgeable of the characteristics of each finance instrument and aware of its possible downsides. The point is important since micro- or small businesses often show deficiencies in matters relating to corporate finance and may well in practice show levels of knowledge similar to an average consumer.Footnote 59 The lack of experience in, or knowledge of, corporate finance is a type of information asymmetry that the Finance Platform Regulations and the mandatory referral scheme more generally leave unaddressed. Prima facie, finance platforms might help to overcome such asymmetries.Footnote 60 However, before drawing conclusions, a more careful assessment would be required, including of their incentives under the platform model and the impact of the pricing structure on these incentives.Footnote 61

Last but not least, it is important to bear in mind that by design, the referral scheme is only targeted at SMEs whose bank funding application was unsuccessful. It is ultimately banks’ willingness to fund SMEs which determines whether they must offer SMEs a referral. The bank referral scheme was a response to tightening bank lending policies in the years that followed the financial crisis. Since then, however, bank lending has picked up and funding success rates are high.Footnote 62 Hence, the referral scheme will only ever matter for a proportion of SME businesses and of this proportion only a proportion will be fundable. As a result, the scheme’s capacity to enable disruption of the status quo by leveraging information sharing and technology was carefully contained. However, neither disruption, nor for that matter pricing (i.e., the interest rates or fees charged by banks to SMEs) were primary objectives. Improving funding rates for unfunded (but not unfundable) SMEs was the main objective and to that extent the idea of a bank referral scheme was a laudable initiative.

4.2 Smart Regulations?

Whilst the basic idea of a referral scheme for SMEs is laudable, its implementation in the Finance Platform Regulations should be open to enquiry. This sub-section seeks to shed a critical light on the regulations, especially with regard to the provisions that underpin the referral duties of banks. The discussion proceeds on the basis of a few simple background assumptions: about the role of incentives in improving performance, or the funding behaviour of many SMEs. In short, this sub-section will argue that the Finance Platform Regulations lack a sufficiently clear appreciation of two issues: firstly, that banks have no real incentives to facilitate a process of financial diversification for their SME customers; secondly, that the point about a bank referral is to make it convenient (as opposed to just making it possible) for SMEs to discover funding alternatives.

Before proceeding, it is worth repeating that the referral scheme has many moving parts and its success—as measured by actual conversion ratesFootnote 63—depends on the successful interplay between different actors: banks, but also finance platforms, SMEs and alternative lenders.Footnote 64 Still for the scheme to be able to function, designated banks must embrace their referral duties. As noted in the introduction, the recent Treasury figures include data on referrals by designated banks. The figures show that during 2017, banks referred a total of 11,080 businesses to finance platforms.Footnote 65 However, few explanations were given with respect to the figures that were disclosed. Some key figures, especially the number of unsuccessful finance applications with designated banks relative to the number of referrals offered by those banks—a key indicator of how diligently banks comply with their referral duties—were not disclosed. The gap in data can be somewhat bridged by considering data that is available in other reports, especially, the SME Finance Monitor which reports periodically on access to finance for SMEs.Footnote 66 Based on qualitative data (surveys with SME businesses), it also provides details on the advice and information that SMEs receive when their application for finance (loans/overdrafts) is declined by banks. Whilst numbers are too small to offer a conclusive picture, the reported figures provide nevertheless an indication of deficiencies in the way in which referral duties are applied in practice.Footnote 67 That said, in the absence of sufficiently comprehensive data, it is yet too early to draw robust conclusions and hence the discussion that follows must be viewed as open to review once more information about the workings of the scheme is made available.

This sub-section begins by studying the lifecycle of a referral and the detailed requirements of the Finance Platform Regulations. Next, it discusses issues affecting banks and SMEs.

4.2.1 The Lifecycle of a Referral Under the Finance Platform Regulations

The lifecycle of a referral is structured around a number of duties and events that are specified in the Finance Platform Regulations. The regulations lay down very detailed rules, but it is plain that they also leave room for differences in implementation.

The event which gives rise to an offer of a referral is an unsuccessful finance application with a designated bank. ‘Finance application’ is a defined term under the regulations. While a finance application can be a request ‘in any form’ for a finance facility,Footnote 68 the Finance Platform Regulations state that such a request must be supported by ‘sufficient information’ for its recipient to make an informed decision as to whether to offer funding.Footnote 69 Alternatively, a request will also be deemed to be a finance application where the recipient has responded to it by asking for additional information to make a decision. These provisions leave room for different interpretations. For example, the meaning of sufficient information is left open in the regulations and in practice it is conceivable that various funding requests will slip through the net because a bank manager treats an enquiry as outside the parameters that define the meaning of a finance application.

A finance application will be considered unsuccessful in two specific instances. Firstly, where a designated bank rejects the finance application.Footnote 70 Secondly, in case where a designated bank offers an SME a finance facility ‘on a different basis’ to the one that the SME sought (hereinafter, an ‘alternative finance facility’) and the SME rejects this alternative finance facility for reasons other than the fees or interests that the SME would be charged. This latter requirement drives the point home that the referral scheme was not designed as a tool for SMEs to find funding at lower cost.

If the finance application is deemed unsuccessful, the next event in a referral’s lifecycle is the actual offer of a referral. In case where a designated bank simply rejects a finance application, the duty to offer an SME a referral will arise at the time where the rejection is first communicated—either in writing or otherwise—to the SME by the designated bank.Footnote 71 However, in case where a bank offered an SME customer an alternative finance facility, the duty to offer a referral will only apply once an SME has informed its bank that it rejects this alternative finance facility.Footnote 72 The regulations are silent on how such a rejection by an SME can be communicated to a designated bank. It is also not clear whether a designated bank can insist that an SME specifies reasons for its rejection.Footnote 73 The regulations merely specify that the duty to offer an SME a referral will apply ‘before the end of the working day following the day on which the business informs the bank that it rejects an offer made by the bank’.Footnote 74 At any rate, in both scenarios—i.e., a rejection of a finance application or an offer of an alternative finance facility that is rejected by an SME—a referral will be contingent on the consent of an SME.Footnote 75 The Finance Platform Regulations are silent on how an SME can indicate its consent. It is worth emphasising that the regulations do not require a bank to seek an SME’s consent in advance of a rejection, for example, at the point where an SME applies for a finance facility with its bank. The duty to seek an SME’s consent will arise at the time where an unsuccessful SME exits, as it were, the finance application. If consent is given, the designated bank must share the designated information with all the finance platforms within a specified time period: that is, before the end of the working day that follows the day on which the SME’s consent is received by the designated bank.Footnote 76

However, if a designated bank does not have all the information that it is supposed to share with finance platforms, the Finance Platform Regulations provide that it must ask an SME to first provide it with the missing information. To be clear, under the regulations, banks are not required to collect this information until the time where an SME consents to a referral.Footnote 77 As pointed out, this latter duty will only arise at the point where an SME exits the finance application process with its designated bank. Once the bank has the missing information, the designated bank has until the end of the working day that follows the day on which it has all the relevant information to refer the designated information.Footnote 78

Once the information is referred to finance platforms, the latter will take centre stage. The finance platform will be under a duty to allow finance providers access to the information that it received from the designated bank.Footnote 79 This will presuppose that a finance provider has requested access to such information and that it has agreed to the finance platform’s terms, including the payments of fees and conditions that must be met.Footnote 80 Crucially, the regulations provide that in the first instance finance providers will only have access to anonymous information.Footnote 81 A finance provider will only be able to access identifying information if it makes a request to this effect and the SME to which the identifying information relates agrees to this information being provided ‘to that finance provider’.Footnote 82 Under the Finance Platform Regulations, this consent is separate and in addition to the initial consent. Finance platforms will be under the duty to request this consent from the SME ‘before the end of the working day following the day on which the platform receives a request for such identifying information from the finance provider’.Footnote 83 Once received, the finance platform, will be required to provide the information ‘by the end of the working day following the day on which the platform receives confirmation’ from the SME.Footnote 84

4.2.2 Banks Have No Incentives to Facilitate a Process of Financial Diversification for SME Customers Under the Mandatory Referral Scheme

It was shown above that designated banks have a key role to play under the bank referral scheme and yet among the actors that are involved, designated banks have the least to gain from a successful referral. Their contribution is vital for the scheme to work, but because banks have few incentives to facilitate a process of financial diversification for SME customers under the scheme, they can be assumed to be the scheme’s weakest link.Footnote 85

To be sure, supporters of the scheme might take the view that a bank’s incentives to make the scheme a success are better than it appears at first. They might point out that the duty to refer SMEs to designated platforms only applies to SMEs which a bank has declined to fund. They might add that the scheme does not seek to encourage competition between banks and alternative lenders with respect to fees or interests rates. Furthermore, they might note that banks only submit basic information to finance platforms, which is not derived data that requires analytical input by banks. Last but not least, they might be more sanguine about the possible benefits of the scheme for banks. They might argue that since banks typically offer SME customers a range of services including business current accounts, the relationship between a bank and an SME customer will not be cut off following a successful referral.Footnote 86 Indeed, they might argue that a bank might well stand to gain if an existing SME customer is able to grow and increase its profitability following successful funding by an alternative lender. What is more, they might add that by being pro-active about the scheme, a bank might also develop a reputation for supporting the SME sector. In short, according to this view, incumbent banks are safe to ignore the bank referral scheme as in the worst case it merely acts as a gateway to alternative lenders that will ‘nibble away at the periphery’Footnote 87 of banks’ businesses.

However, upon reflection (and short of empirical validation) many of these arguments must be taken with caution. Whilst different banks might draw different conclusions about the benefits of the scheme, it is not obvious that an incumbent bank will consider that it has much to gain from referring an SME customer to a finance platform—whether in terms of trust building with its SME customer or a fortiori in terms of improving its own profitability. Admittedly, designated banks are free to join the lending panel of finance platforms and to compete for SME funding if it is in their commercial interest to do so. However, a bank’s duty to refer is mandated by law; it is not the outcome of a commercial partnership with mutual rights and obligations between parties.Footnote 88 A mandatory referral has no quid pro quo for an incumbent. Arguments that link a referral to building trust between a bank and an SME customer, or to building a reputation for supporting the SME sector, are also questionable since, again, the duty to refer is a legal requirement. What is more, it might just as well be argued that a successful referral risks alienating SME customers that have seen their application rejected by a relationship bank, but are considered viable investments by alternative lenders that have no prior relationship with an SME. It is also hard to see what a designated bank has to gain if a referral proves unsuccessful and an SME customer is turned down by alternative lenders. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, finance platforms do not just offer a gateway to specialised niche lenders. They offer a gateway to competitors which offer substitute products: established banks as well as challenger banks which will be in a position to offer SMEs a full range of banking products, including current accounts. In sum, under a mandatory referral scheme, a designated bank will have little reason to think that its ongoing relationship with an SME customer will be strengthened following a referral. Indeed, arguably incumbents are more likely to take the opposite view and see mandatory referrals as a threat to their revenue streams and as a gateway to competitors in the SME funding market.

Admittedly, the regulations establish legal duties with respect to referrals. Designated banks must offer a referral in the case of an unsuccessful finance application. It is the law. However, even where banks comply with the letter of the law,Footnote 89 they have no incentives to comply with the spirit of the scheme. The difference between the former and the latter may in turn determine whether referrals are treated purely as a compliance exercise or as a means to help SME to overcome information barriers and find potential sources of funding. The Finance Platform Regulations arguably reinforce this issue by establishing detailed rules and duties that can be satisfied without having regard to the spirit of the scheme. Thus, in practice, there will be various ways to bridle the scheme whilst still complying with the letter of the law: because of excessive delays in making funding decisions or communicating the outcome of a finance application; because of the manner in which an offer of a referral is communicated; because of the need for repeated interactions; or because of the way in which an SME customer is asked to communicate consent to a referral following an unsuccessful finance application.

4.2.3 Bank Referrals are About Convenience

Besides designated banks, the success of the referral scheme also depends crucially on the behaviour of SMEs. Their contribution is vital to improve their funding prospects. Clearly, they must at the outset be willing to consider alternative sources of finance. Such willingness might be improved by a number of factors: an awareness of alternative sources of finance, confidence in dealing with alternative lenders, but also a hassle free referral process.

Indeed, from an SME’s point of view, a core benefit of the mandatory referral scheme is prima facie the promise of an easy and convenient way to reach a range of suitable alternative lenders at the point where an application for funding with an incumbent bank proves unsuccessful. It is worth bearing in mind in this context that many SMEs are often unwilling to devote time and effort on finding external funding.Footnote 90 Moreover, if they search for alternative sources of funding, they might do so outside business hours.Footnote 91 Hence, convenience is often cited as among the main reasons for SMEs to seek funding with their high street bank. Moreover, since it is always open to an SME to ‘self-refer’ to a designated platform,Footnote 92 the promise of greater convenience must be considered an important factor for choosing a bank referral over a self-referral.

Promises of greater convenience or user-friendliness are typically value propositions of the Fintech sector. Finance platforms too, promise SMEs a user-friendly experience and (prima facie) their online portals, which are at the interface between SMEs and finance providers, will make it easier to implement the detailed requirements of the Finance Platform Regulations. Likewise, designated banks and finance platforms have successfully used technology to organise information sharing. Promises of greater convenience can also be associated with other initiatives in the consumer or SME banking space—think of the open banking initiative in the UK and the choice in favour of an open banking API as a means to allow seamless information sharing. However, under the Finance Platform Regulations, the interactions between a designated bank and an SME customer remain firmly grounded in an ‘analogue’ world. Thus, the regulations do not seek to facilitate communications between banks and unfunded SME customers; they are silent on how an SME customer can indicate its consent; they ‘back-load’ the duties of designated banks to ask for an SME’s consent, to ask for missing information, etc. However, if convenience is an important factor for SMEs to avail themselves of a bank referral, the Finance Platform Regulations must not only make it possible for information to be referred to finance platforms; they must seek to reduce frictions in the referral process. The latter is a more demanding standard to meet since it not only requires imposing duties on banks to share designated information; it requires having regard to the user-friendliness of the referral process. Clearly implementing this higher standard is a difficult task. However, the bottom line is that because banks have no incentives to be pro-active about the referral scheme, they cannot be expected to reduce frictions in the implementation of the regulations of their own volition.

4.3 Smart(er) Regulations?

This final sub-section reflects on ways to ease the referral process by building on earlier insights. It seeks to discuss critically several possible options: improving banks’ incentives, extending the use of technology, ‘frontloading’ duties for designated banks and finally attempting to implement the spirit of the scheme in the letter of the regulations.

4.3.1 Improving Banks’ Incentives?

Given the pathology that I described above, improving a bank’s incentives to play a more proactive role in the referral scheme appears to be an obvious starting point for discussing ways in which the bank referral scheme could be improved. Prima facie, this might require offering banks financial incentives, for example, by making a referral subject to information access fees. The basic idea of information access fees is by no means new. For example, Jappelli and Pagano consider the merit of access fees in relation to the sharing of credit information.Footnote 93 They are concerned that mandatory sharing might create free rider issues which in turn might disincentivise banks that are subject to such a duty to invest in screening and monitoring activities in the first place.Footnote 94 Hence, according to the authors, access fees might potentially offer a way to neutralise such disincentives as banks would be compensated for producing credit information.

However, information access fees are unlikely to be an appropriate response in the case of mandatory referrals. Unlike soft or inferred data which a bank produces and which is often based on a bank’s relationship with an SME customer, the information that banks must refer under the referral scheme is basic raw information about an SME and its funding needs. It does not require analytical input by a bank. The role of banks is merely to pass on the information. Moreover, allowing banks to benefit financially from their decisions to reject finance applications by SME customers—recall that referral duties are only triggered if a finance application with a designated bank proves unsuccessful—would prove politically unpalatable. Finally, it is questionable whether access fees would be effective in neutralising disincentives if what is at risk from an incumbent bank’s point of view is its ongoing relationship with its SME customer, and related to this, the prospect of greater competition and a loss of revenue streams. Recall that the referral scheme offers a gateway to a wide range of possible lenders, including competitors that offer substitute products.

To be sure, prima facie, a bank’s incentives could also be improved through commercial partnerships that do not involve direct financial compensation in the form of access fees. Indeed, if market forces would produce such referral schemes naturally, the need for a mandatory referral scheme would be severely diminished. There have been examples of commercial tie-ups between incumbent banks and alternative finance providers in recent years. A prominent example is the partnership between Santander UK and Funding Circle (a peer-to-peer lender) in 2014. Under the partnership—the first of its sort in the UK—the former agreed to refer small business customers that did not secure funding with Santander, to Funding Circle.Footnote 95 In return, Funding Circle committed to promote Santander’s services such as current account or cash management services.Footnote 96 Although the precise terms of the partnership are not known, the partnership between Santander and Funding Circle does not appear to involve information access fees. Hence, there is clearly scope for voluntary referral initiatives. However, whether such schemes are performing well or can serve as alternatives to a mandatory scheme cannot be assessed in the absence of empirical data. Prima facie, it appears unlikely that market forces will naturally produce a scheme comparable to the bank referral scheme, which as noted, offers SME businesses access to a wide range of alternative lenders (including challenger banks).Footnote 97 Moreover, the referral duties of Santander under its deal with Funding Circle are almost certainly more limited than under the bank referral scheme.Footnote 98

4.3.2 Extending Technology?

Technology plays an important role in information sharing between banks and finance platforms and in seeking to match SMEs with potential lenders. However, as pointed out, the same is not true of the relations between a designated bank and an SME customer. Here, interactions potentially risk to be protracted because of ineffective methods of communication, unnecessary delays, etc. Arguably technology could play a part in dealing with those issues. By requiring that the referral process be entirely managed online, the process would become more streamlined. It would help those SMEs that mostly seek funding outside business hours; it would also avoid inconsistencies in the way in which bank managers communicate the offer of a referral or the merit of the scheme to SME customers. SMEs would continue to be in charge of the process via consent requirements. However, it is also plain that streamlining the process in such a manner would be intrusive on banks’ relationships with SME customers and how they communicate funding outcomes to them.

4.3.3 Frontloading?

We have seen that under the regulations, banks’ duties with regard to the referral process are backloaded: they will not arise until a finance application is deemed unsuccessful (see Table 1). From a bank’s point of view, back-loading is more attractive than front-loading. This is because backloading reduces the bank’s prospect of facing competition from alternative lenders prior to making a funding decision with respect to an SME customer.

In the case of frontloading, some of a bank’s duties under the referral scheme would arise at the time of a finance application with a designated bank. There are several duties that could be frontloaded. For example, a bank could be required to collect all the designated information at the time where a finance application is made.Footnote 99 Under the regulations, there is no such duty. In case where a bank misses designated information, it is only required to ask for such information at the time where an SME agrees to a bank referral: that is after a bank has declined a finance application. The duty of a bank to provide generic information on the mandatory referral scheme could also be frontloaded. Thus, a designated bank could be required to provide written information on the mandatory referral scheme and on finance platforms at the time of an application,Footnote 100 whilst the duty for a designated bank to refer information to a finance platform could continue to depend on the outcome of a finance application with a bank. The requirement for a bank to seek an SME’s consent to a referral could also be frontloaded. Again, in such a case, the actual referral duty would continue to depend on the funding outcome. Hence, it would only arise in case where a finance application with a designated bank proved unsuccessful.

Frontloading some of the duties would help to raise awareness of the scheme and generally ease the referral process. Specifically, it would help to alleviate informational issues (a lack of knowledge of the government-backed referral scheme) and contribute to avoiding the prospect of potentially protracted interactions later on. A more drastic change to the scheme would be to require banks to offer SME customers a referral at the time where an SME makes a funding application with its bank.Footnote 101 However, such a change would be a step too far. It would fundamentally alter the nature of the referral scheme as it exists today.

4.3.4 Implementing the Spirit of the Scheme?

The purpose of the referral scheme is to offer SMEs an easy and convenient way to discover alternative sources of funding when their finance application with a designated bank is unsuccessful. By fulfilling their duties in a timely and pro-active manner, banks can play a key role in ensuring that the referral scheme meets its purpose. However, as pointed out, banks have few incentives to be proactive about the scheme and compliance with the letter of the regulations can still undermine the spirit of the scheme. Arguably the potentiality of behaviour that bridles the scheme—instances of ‘creative compliance’Footnote 102—could be diminished by attempting to implement the spirit of the scheme into the letter of the regulations via broad and open-textured principles.Footnote 103 Such principles could, for example, require incumbent banks to act in a manner that allow SME customers to make timely decisions on the merit of a referral or require them to act in a way that facilitates the referral process for SME customers. Ultimately, it would be for the FCA when exercising its monitoring and enforcement role, to ensure that incumbent banks act in a manner that complies with their detailed duties, but also with such open-textured principles.

5 Conclusion: ‘Undisruption’ in the SME Funding Market

Disruption is a notion that is often associated with online platforms or the use of technology to challenge incumbents. Finance platforms, which are central to the mandatory referral scheme, seek to harness technology in order to offer more effective matchmaking in the SME funding space. However, they have clearly not facilitated disruption by exploiting their matchmaking role and leveraging their informational advantages and technology. Banks will continue to play a key role in the SME funding market. They will continue to benefit from their information advantages and their ongoing relationships with SME customers.

To be fair, unlike initiatives such as open banking which has much greater disruptive potential, the mandatory referral scheme was not designed as a tool to enable disruption. Disrupting the status quo will depend on a variety of factors, including the availability of alternative finance providers, and—crucially—SMEs that are willing to engage with finance platforms and alternative lenders. Moreover, as shown in this article, the bank referral scheme is aimed only at a proportion of SME businesses whose funding applications were rejected by designated banks and it will ultimately only help a proportion of this proportion: that is, those SME businesses that are fundable and meet the lending or risk appetite of an alternative lender (e.g., a challenger bank or a niche lender). This paper argued therefore that the bank referral scheme was better described as a sort of ‘clearing’ scheme for unfunded (but not unfundable) SME businesses. As far as finance platforms are concerned, it is plain that to make a more meaningful impact as matchmaker in the SME funding market, they must ultimately achieve visibility independently of the referral scheme and generate online traffic from SMEs that are not referred by incumbent banks.

It is perhaps somewhat ironic that the sharing of very basic information under the referral scheme is subject to a more cumbersome process in law than the sharing of more complex data such as account data under initiatives such as open banking. This article sought to reflect on ways in which the referral process could be eased. Clearly not all of the options that were put forward for discussion have something to offer in practice. However, some form of ‘frontloading’ or giving greater consideration to the spirit of the scheme in the Finance Platform Regulations are options that might be worth exploring in more detail in the future, once more information about the performance of the scheme and the role of each participant is made available.

Notes

See, e.g., ‘Smaller businesses offered route to alternative finance’, Financial Times, 1 November 2016.

European Commission (2017).

The data showed that within the period under review (9 months), 230 small businesses gained funding through the scheme and that in total £3.8 million were raised from alternative lenders. See HM Treasury, ‘Matchmaking scheme helps businesses find £4 million of finance’, 11 August 2017, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/matchmaking-scheme-helps-businesses-find-4-million-of-finance.

See also ‘Bank lending “flop” put under review’, The Times, 19 April 2017 noting that the Treasury had been ‘secretive about the scheme’s performance’ and that finance platforms had ‘been told not to share any data’.

HM Treasury (2018b), p 3.

For the avoidance of doubt, the concept of ‘clearing’ here is of course entirely unrelated to the notion of clearing in the post trade space.

See also Explanatory notes to the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, para. 14.

In the context of the Capital Markets Union, see my own, earlier, contribution in Schammo (2017).

For a fuller assessment on which this section draws, see Schammo (2017), pp 279–285.

See e.g., European Commission (2015), p 13.

Schammo (2017), p 282.

CMA (2016), p 298.

Schammo (2017), p 282.

See in this context British Business Bank (2018), pp 15–17.

See e.g., CMA (2016), pp 299–300.

See also BDRC (2018), p 47 noting with respect to UK SMEs that only ‘24% of SMEs had a financially qualified person looking after their finances. This became more likely as business size increased: 20% of 0 employee SMEs had a financial specialist compared to 32% of those with 1–9 employees, 48% of those with 10–49 employees and 70% of those with 50–249 employees’.

British Business Bank (2018), p 16.

E.g. CMA (2016), p xxv.

HM Treasury (2014a), p 84.

Regulation 9 of the Finance Platform Regulations.

Regulation 10(3). Note that pursuant to regulation 10(1), to be designated a bank must be either an institution that is deemed a bank for the purposes of Part 1 of the Banking Act 2009; or a finance provider that is a member of a banking group according to section 1164 of the 2006 Companies Act.

Regulation 10(4).

AIB Group (UK) Plc (t/a First Trust Bank); Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc; Barclays Bank Plc; Clydesdale Bank Plc; Northern Bank Ltd (t/a Dankse Bank); HSBC Bank Plc; Lloyds Banking Group Plc; Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc; Santander UK Plc. See HM Treasury (2018a).

CMA (2016), p xxvii.

HM Treasury (2014b), p 6.

Regulation 4(3) of the Finance Platform Regulations.

Schedule to the Finance Platform Regulations.

The scheme was implemented in the Small and Medium Sized Business (Credit Information) Regulations 2015 [SI 2015/1945] (hereinafter, the Credit Information Regulations).

For details see regulation 6 of the Credit Information Regulations, in particular the requirement for SMEs to consent to the sharing of such information.

For details, see Schammo (2017), p 291.

See CMA (2016).

The open banking initiative does not solely aim to facilitate information sharing. It also seeks to make it easier for third party providers to initiate payments (with the consent of the payment service user). It is also worth noting that not all banks are required to comply with open banking. It applies currently to the following banks (or building societies): Allied Irish Bank, Bank of Scotland, Barclays, Danske, Halifax, HSBC, Lloyds Bank, Nationwide, NatWest, Santander, The Royal Bank of Scotland and Ulster Bank. See for details https://www.openbanking.org.uk/.

Open Data Institute and Fingleton Associates (2014), p 16.

See the provision on account information service providers under the second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) (Directive (EU) 2015/2366 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on payment services in the internal market, amending Directives 2002/65/EC, 2009/110/EC and 2013/36/EU and Regulation (EU) No. 1093/2010, and repealing Directive 2007/64/EC [2015] OJ L337/35). See also the provisions on data portability under the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation or GDPR) [2016] OJ L119/1). Note that the UK open banking initiative builds on the provisions of the PSD2.

European Commission (2018). The Commission consulted earlier on the issue of information sharing in relation to credit and financial data. See European Commission, ‘FinTech: a more competitive and innovative European Financial Sector’ (Consultation Document, undated), available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2017-fintech-consultation-document_en_0.pdf.

European Commission, ‘Summary of contributions to the “Public consultation on FinTech: a more competitive and innovative European financial sector”’ (undated), p 10, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2017-fintech-summary-of-responses_en.pdf.

See the June 2017 high-level principles on feedback given by banks on declined SME credit applications which are available at https://www.ebf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/High-level-principles-on-feedback-given-by-banks-on-declined-SME-credit-applications.pdf.

The three platforms are Alternative Business Funding (https://www.alternativebusinessfunding.co.uk), Funding Options (https://www.fundingoptions.com) and Funding Xchange (https://www.fundingxchange.co.uk). A fourth platform (Bizfitech) no longer operates as finance platform.

See regulation 12 of the Finance Platform Regulations.

It is perhaps worth noting that the Finance Platform Regulations do not make authorisation as credit broker a pre-condition to a designation.

Rochet and Tirole (2006), p 126.

Rochet and Tirole (2006).

Specifically, regulation 6(7) states that a platform cannot charge any fee to SMEs ‘in relation to the provision of information about a finance application made by that business’.

The mandatory referral scheme will help finance platforms to make contact with SMEs. However, following a referral, SMEs must be willing to engage with finance platforms. Moreover, since referrals are dependent on the success rate for bank finance, finance platforms will need to add independently additional traffic to the platform in order to reduce their dependencies. The designation of finance platform might be useful in this context by increasing visibility and adding to the credibility of the credit broking business.

Regulation 6(1)(b).

Note that SMEs are a very diverse group and in terms of regulatory protections will not all be treated in the same way. Size remains an important consideration when considering the protections available to SMEs. See e.g., in this context, FCA (2015).

The FCA has stated that it will carry out its functions according to the same principles that it applies elsewhere. See FCA (2016), pp 2–3. Note that the Finance Platform Regulations also extend the jurisdiction of the Financial Ombudsman Scheme (regulation 14). See also in this context the recent consultation by the FCA on the access of SMEs to the Financial Ombudsman Scheme (FCA 2018).

Regulation 17.

It is worth noting that the demand for equity finance among SMEs is especially low. See BDRC (2018), p 12.

With regard to peer-to-peer lending, see Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (2017), p 21 noting that in 2016 the peer-to-peer business lending volume in the UK was equivalent ‘to just over 15% of all bank lending to small businesses’. Meanwhile, peer-to-peer lending was equivalent to 6.56% of all new loans lent to SMEs by banks in 2016, which is lower than for smaller businesses but still an increase from 0.3% in 2012 (p 20).

A general definition of finance provider is found in section 7(1) of the SBEE Act which states that ‘finance provider’ means ‘a body corporate that (a) lends money or provides credit in the course of a business, (b) arranges or facilitates the provision of debt or equity finance in the course of a business, or (c) provides, arranges or facilitates invoice discounting or factoring in the course of a business, and regulations under sections 4 and 5 may make further provision for the purpose of determining which finance providers they apply to’. See also regulation 2(2) of the Finance Platform Regulations.

See Sect. 3.2 above.

The type of business that qualifies as an SME for the purposes of the mandatory referral scheme is defined in the SBEE Act and the Finance Platform Regulations which provide that only businesses with an address in the UK; that carry out commercial activities as their main activity; and which do not belong to a group that has an annual turnover equal or greater than £25 million are considered SMEs for the purposes of the Treasury Regulations. Regulation 2(1).

The 2018 Treasury figures (HM Treasury (2018b), p 4) show that actual contacts by SMEs with finance platforms are lower than the number of bank referrals. Since the beginning of the scheme, the cumulative contact rate is 53%. However, the information that the Treasury released does not allow drawing conclusions on the reasons behind this figure. There are various possible explanations for why an SME may not engage with platforms, e.g., because of an SME’s aversion to alternative finance, because it views the matching process with alternative lenders as cumbersome or as unlikely to make a difference. Note that in practice many SMEs choose to avoid external finance altogether. On this latter point, see e.g. British Business Bank (2018), p 17 and BDRC (2018), p 10, noting that the demand for finance among SMEs remains ‘muted’.

See also n. 16 above in this context.

The Finance Platform Regulations do not create duties in this respect. As credit brokers, finance platforms will be subject to the duties towards clients that come with this status.

At the time of writing, there is little hard data available on how effective finance platforms have played their role. Some soft information—in the form of customer reviews—is available through sites such as Trustpilot (https://uk.trustpilot.com). The two platforms that have a profile on Trustpilot (Funding Options and Alternative Business Finance) are both rated excellent.

See BDRC (2018), p 154, reporting that success rates for bank loans and overdrafts for the 18 months to Q4 2017 were (provisionally) 80%. Note that the success rates for first time applicants is noticeably lower (provisionally reported at 50% in the period under review).

The Treasury (HM Treasury (2018b), p 5) reports that the cumulative conversion rate between Q4 2016 and Q2 2018 is 9.02% when comparing the number of SMEs that have engaged with platforms following a referral with the number of SMEs that received finance via a platform.

See Sect. 4.1 above for details.

HM Treasury (2018b), p 4. Since the scheme launched in November 2016, a total of 18,881 bank referrals were made.

BDRC (2018).

E.g. with respect to interviewees who applied unsuccessfully for a loan between October 2016 and December 2017 (42 respondents), only 3 reported that they had been offered a referral (BDRC 2018, p 176). Of those interviewees who unsuccessfully applied for an overdraft between October 2016 and December 2017 (38 respondents), only 2 reported that they were offered a referral (BDRC 2018, p 163).

Regulation 2(1). A finance facility is defined as ‘a facility which provides access to finance which is denominated in sterling and is a loan agreement, an overdraft agreement, a credit card account, an invoice discounting or factoring agreement, a hire purchase agreement or a finance leasing agreement’ [regulation 2(1)]. Note that under regulation 3(3), the referral duty does not apply where ‘(a) the value of the finance facility is less than £1000; (b) the facility applied for is sought for a period of less than 30 days; (c) the bank is aware that the business is subject to a statutory demand for payment, enforcement proceedings or other legal proceedings in relation to payment obligations arising under an existing finance facility; or (d) the bank is aware that the business is subject to a formal demand’.

Regulation 2(1).

Regulation 2(3)(a).

Regulation 4(2)(a).

Regulation 4(2)(b).

The language of regulation 2(3)(b)(ii) and especially the reference to ‘any reasons’ seem to suggest that SMEs are not required to specify them.

Regulation 4(2)(b).

Regulation 3(4).

Regulation 5(1).

Regulation 4(1)(b).

Regulation 5(2).

Regulation 6.

Regulation 6(1).

Regulation 6(2).

Regulation 6(3).

Regulation 6(4).

Regulation 6(5).

Highlighting banks’ lack of incentives in the context of past voluntary signposting initiatives, see Schammo (2017).

Schammo (2017), p 295.

Christensen et al. (2015), p 48.

Elsewhere there have been several tie-ups between banks and alternative finance providers. For example, Santander UK tied up with Funding Circle (a peer-to-peer lender) in 2014.

In fact, there are some reports that this might not always be the case. See n. 67 above.

CMA (2016), p 299.

See e.g. the submissions of Funding Circle (a peer-to-peer lender) to the CMA’s retail market investigation in which Funding Circle noted that ‘[h]alf of our applications come outside of working hours, showing the need for flexibility when it comes to searching for finance’. See Funding Circle, ‘Competition and Markets Authority, Retail banking market investigation’ (undated), available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57613349e5274a0da3000063/funding-circle-response-to-pdr.pdf.

See Sect. 3.1 above.

Jappelli and Pagano (2000).

Jappelli and Pagano (2000), p 15.

‘Funding Circle & Santander announce partnership to support thousands of UK businesses’, Funding Circle, 18 June 2014, available at https://www.fundingcircle.com/blog/2014/06/funding-circle-santander-announce-partnership-support-thousands-uk-businesses/.

See ‘Santander in peer-to-peer pact as alternative finance makes gains’, Financial Times, 17 June 2014. Santander also tied up with Crowdfunder in 2016. See ‘Santander UK enters partnership with Crowdfunder’, Financial Times, 4 October 2016.

As noted earlier, the UK government took the view that voluntary signposting initiatives by the banking sector had not gone far enough. See n. 25 above (but with no reference to the Santander Funding Circle deal).

Prima facie, this voluntary ‘referral’ system does not involve a direct referral by Santander to Funding Circle. Referrals are meant to take place on Santander’s webpage or in letters to Santander’s customers. See n. 95 above.

Given the basic nature of this information, one would assume that a bank will at any rate collect this information as part of its assessment of a finance application.

Under the regulations, the duty to provide SMEs with generic platform information only arises after a finance application is deemed unsuccessful and if a business does not agree to a bank referral. The aim is to raise an SME’s awareness of the scheme, which can always decide to ‘self-refer’.

Finance platforms have (unsurprisingly) been supportive of this approach and front-loading more generally. See ‘Referrals for bank-jilted small firms still conspicuously absent’, The Telegraph, 10 August 2015, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/11787286/Referrals-for-bank-jilted-small-firms-still-conspicuously-absent.html.

McBarnet and Whelan (1991).

See Baldwin et al. (2012), p 232.

References

Akerlof A (1970) The market for ‘lemons’: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Q J Econ 84:488–500

Baldwin R, Cave M, Lodge M (2012) Understanding regulation: theory, strategy, and practice. OUP, Oxford

BDRC (2018) SME finance monitor Q4 2017. https://www.bdrc-group.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/RES_BDRC_SME_Finance_Monitor_Q4_2017.pdf. Accessed 6 Sep 2018

British Business Bank (2018) Small business finance markets 2017/18. https://www.british-business-bank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Small-Business-Finance-Markets-2018-Report-web.pdf. Accessed 6 Sep 2018

Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (2017) Entrenching innovation—the 4th UK alternative finance industry report. https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/research/centres/alternative-finance/downloads/2017-12-ccaf-entrenching-innov.pdf. Accessed 6 Sep 2018

Christensen C, Raynor M, McDonald R (2015) What is disruptive innovation? Harv Bus Rev 93:44–53

Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) (2016) Retail banking market investigation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57ac9667e5274a0f6c00007a/retail-banking-market-investigation-full-final-report.pdf. Accessed 6 Sep 2018

European Commission (2015) Green paper: building a Capital Markets Union. COM(2015) 63 final

European Commission (2017) Addressing information barriers in the SME funding market in the context of the Capital Markets Union. SWD(2017) 229 final/2

European Commission (2018) FinTech action plan: for a more competitive and innovative European financial sector. COM(2018) 109/2

Financial Conduct Authority (2015) Our approach to SMEs as users of financial services. Discussion Paper DP15/7. https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/discussion/dp15-07.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2019

Financial Conduct Authority (2016) Guidance on small and medium sized business (credit information) regulations and small and medium sized business (finance platform) regulations. FG16/4. https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/fg16-4.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2019

Financial Conduct Authority (2018) Consultation on SME access to the financial ombudsman service and feedback to DP15/7: SMEs as users of financial services. CP18/3. https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/ps18-21.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2019

HM Treasury (2014a) Budget 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/293759/37630_Budget_2014_Web_Accessible.pdf. Accessed 9 Sep 2018

HM Treasury (2014b) Help to match SMEs rejected for finance with alternative lenders. http://www.parliament.uk/documents/impact-assessments/IA14-20D.pdf. Accessed 9 Sep 2018

HM Treasury (2018a) Notice of designation: small and medium sized business (finance platforms) regulations 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/designation-of-banks-and-finance-platforms-for-finance-platforms-regulations/notice-of-designation-small-and-medium-sized-business-finance-platforms-regulations-2015. Accessed 9 Sep 2018

HM Treasury (2018b) Bank referral scheme: official statistics. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/737136/Bank_Referral_Scheme_Official_Statistics_Publication_-_August_2018.pdf. Accessed 6 Sep 2018

Jappelli T, Pagano M (2000) Information sharing in credit markets: a survey. Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance, Working Paper No 36. http://www.csef.it/WP/wp36.pdf. Accessed 6 Sep 2018

McBarnet D, Whelan C (1991) The elusive spirit of the law: formalism and the struggle for legal control. Mod Law Rev 54:848–873

Open Data Institute and Fingleton Associates (2014) Data sharing and open data for banks: a report for HM Treasury and Cabinet Office. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/382273/141202_API_Report_FINAL.PDF. Accessed 6 Sep 2018

Rochet J-C, Tirole J (2006) Two-sided markets: a progress report. RAND J Econ 37:645–667

Rysman M (2009) The economics of two-sided markets. J Econ Perspect 23:125–143

Schammo P (2017) Market building and the Capital Markets Union: addressing information barriers in the SME Funding Market. Eur Co Financ Law Rev 2:271–313

Stiglitz J, Weiss A (1981) Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. Am Econ Rev 71:393–410

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions