Abstract

Background

Use of electronic health records (EHRs) is associated with physician stress and burnout. While emergency departments and subspecialists have used scribes to address this issue, little is known about the impact of scribes in academic primary care.

Objective

Assess the impact of a scribe on physician and patient satisfaction at an academic general internal medicine (GIM) clinic.

Design

Prospective, pre-post-pilot study. During the 3-month pilot, physicians had clinic sessions with and without a scribe. We assessed changes in (1) physician workplace satisfaction and burnout, (2) time spent on EHR documentation, and (3) patient satisfaction.

Participants

Six GIM faculty and a convenience sample of their patients (N = 325) at an academic GIM clinic.

Main Measures

A 21-item pre- and 44-item post-pilot survey assessed physician workplace satisfaction and burnout. Physicians used logs to record time spent on EHR documentation outside of clinic hours. A 27-item post-visit survey assessed patient satisfaction during visits with and without the scribe.

Key Results

Of six physicians, 100% were satisfied with clinic workflow post-pilot (vs. 33% pre-pilot), and 83% were satisfied with EHR use post-pilot (vs. 17% pre-pilot). Physician burnout was low at baseline and did not change post-pilot. Mean time spent on post-clinic EHR documentation decreased from 1.65 to 0.76 h per clinic session (p = 0.02). Patient satisfaction was not different between patients who had clinic visits with vs. without scribe overall or by age, gender, and race. Compared to patients 65 years or older, younger patients were more likely to report that the physician was more attentive and provided more education during visits with the scribe present (p = 0.03 and 0.02, respectively). Male patients were more likely to report that they disliked having a scribe (p = 0.03).

Conclusion

In an academic GIM setting, employment of a scribe was associated with improved physician satisfaction without compromising patient satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In the USA, 83% of the office-based physicians reported using electronic health records (EHRs) in 2014.1 EHR use has been associated with improvements in clinical care, including higher guideline adherence and fewer medication errors, without a decrease in patient satisfaction.2,3 However, EHR use has also been shown to impede patient–doctor communication, increase physician attrition rates, and contribute to physician burnout.3,4,5,6,7,8,–9

A potential solution to address EHR-related dissatisfaction is the use of medical scribes. Medical scribes are trained personnel who provide physicians with documentation assistance and perform other EHR tasks.10 In emergency departments and subspecialty clinics, scribes have led to increased physician productivity and revenue and improvements in physician and patient satisfaction.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,–20

In clinical practice, there are several models for incorporating scribes. One common model is an in-house scribe model, in which a clinical practice undertakes the training and management of scribes. The in-house scribe model typically involves a licensed practical nurse (LPN) or medical assistant (MA) whose clinical role is expanded to include EHR documentation assistance and clinic navigation.21,22,–23 To date, three studies in primary care have examined the role of in-house scribes and found improvements in physician quality of life, physician burnout, and patient satisfaction.24,25,26,–27

Resource-tight academic practices may not have the capacity to take on the training and management of scribes. A second common model is an outsourced scribe model, in which the training and management of scribes for documentation assistance are outsourced to an outside company.22 In primary care, studies of outsourced scribes have been small and in unique settings (i.e., rural clinic and academic safety net hospital).19,24 Physician satisfaction increased in both the rural and the academic safety net setting, while patient satisfaction was mixed.19,24

Our study aims to (1) evaluate the impact of using an outsourced scribe model on physician workplace satisfaction, burnout, and time spent on EHR documentation and (2) explore patient satisfaction and attitudes towards scribes at an urban, academic general internal medicine (GIM) clinic.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

We implemented a scribe pilot for the faculty practice at an academic GIM clinic at the University of Chicago (UC) between April and June 2017. From a pool of 15 interested faculty members, six were selected based on clinic schedules to allow for employment of a full-time scribe (Monday–Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m.); gender and number of years in practice were also taken into account. We also intentionally chose one faculty member who was a clinical researcher, because their experience may be different than clinical educators. Participating faculty had between one and four 4-h clinic sessions a week. Study authors were excluded from the pilot. A convenience sample of patients who had clinic visits with these physicians during the pilot was surveyed.

Intervention

A scribe company (PhysAssist Scribes, Inc.) provided one full-time scribe during the pilot. The scribe was a 20 to 30-year-old woman with 1 year of scribe experience. She received 40 h of training on medical terminology and compliance and 4 h of UC-specific EHR ambulatory training. Before the pilot, the scribe shadowed each physician for one clinic session and our research team met with the scribe and participating faculty to review responsibilities and best practices.

At a minimum, we required that each faculty work with the scribe for one clinic session per week, and we divided the remaining time that the scribe was available across the faculty. Clinic sessions with a scribe comprised 25–80% of the total clinic sessions for each physician. During clinic visits, the scribe logged into the EHR on a separate laptop computer, loaded the note template preferred by the physician, and documented the encounter. In addition, the scribe prompted physicians about indicated health maintenance items in real time and typed patient instructions and education information, if directed. Due to medical center policies, the scribe did not pend and route orders; physicians entered orders during the visit. At the end of each clinic session, the scribe routed all notes to the physician to review, edit, sign, and close.

Measures

The main outcomes were physician workplace satisfaction and burnout, time spent on EHR documentation, patient satisfaction with doctor–patient relationship, and patient and physician attitudes towards scribes. Based on a literature review, a 21-item pre- and 44-item post-pilot physician surveys were developed, which incorporated the validated single-item burnout assessment, questions adapted from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Physicians and Systems Clinician & Group Survey (CG-CAHPS), and questions about attitudes towards having a scribe (Online Appendix 1).28,29 The 27-item patient survey incorporated CG-CAHPS questions and included Likert and open-ended questions about attitudes towards scribes (Online Appendix 1).29

Data Collection

Faculty completed a survey 1 week before the pilot and a survey 1 week after the pilot. All survey results were confidential and analyzed by non-physician study team members (AP and WW). During the pilot, physicians logged time spent on documentation for four scribed and four non-scribed clinic sessions (Online Appendix 2). After the pilot, physicians completed a standardized exit interview with a study author (WWL) (Online Appendix 3). Patients received a survey from an MA before seeing their physician and completed it prior to leaving the clinic.

Data Analysis

Survey data were entered in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system.30 Analysis was performed using Stata 14 and SAS 9.4. Standard descriptive statistics were used for physician surveys, and paired t tests were used to analyze data from physician logs on time spent on documentation.

For patient satisfaction and attitudes towards scribes, we used logistic regression and generalized linear mixed (GLM) models to compare responses for patients who had clinic visits with vs. without a scribe. The GLM models accounted for clustering effects of patient responses within physician. Models initially included the potential covariates of age, gender, and race, and then through the backward model selection procedure, only covariates significantly associated with outcomes were included in final models. We also performed subgroup analyses by patient age, gender, and race to investigate the consistency of effects across subgroups.

For patient satisfaction, we compared “strongly agree” vs. “agree,” “neutral,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree,” due to a high baseline level of patient satisfaction. For other outcomes, strongly agree and agree responses were collapsed and analyzed as agree; and strongly disagree, disagree, and neutral were collapsed as disagree. For negative-valence questions, responses were reverse coded so that strongly agree, agree, and neutral were compared to disagree and strongly disagree. Because logistic regression and GLM models produced very similar results, we only present results from the logistic regression models.

This project was approved as a quality improvement project by the University of Chicago and did not require approval by the Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Six faculty physicians (three male, three female) with a range of 5 to 29 years in practice participated in the study.

Physician Workplace Satisfaction and Burnout

Pre-pilot, all six physicians agreed that they felt rushed during clinic; all disagreed with this statement post-pilot. Only two (33%) were satisfied with clinic workflow pre-pilot, but all physicians were satisfied post-pilot. Before the pilot, five physicians (83%) agreed that “too much time in clinic is spent working on the computer,” whereas post-pilot, no physicians agreed. Only one physician reported burnout symptoms at baseline, which did not change post-pilot. No change in satisfaction with the doctor–patient relationship or physician satisfaction with quality of documentation was found (Table 1).

Physician EHR Use

During the pilot, physicians reported spending less time on post-clinic EHR documentation per clinic session when comparing sessions with vs. without a scribe (1.65 ± 1.32 vs. 0.76 ± 0.76 h, p = 0.02). Pre-clinic documentation time did not differ for visits with vs. without the scribe (0.39 ± 0.37 vs. 0.29 ± 0.40 h, p = 0.16).

Pre-pilot, five physicians (83%) were dissatisfied with sufficiency of time for documentation, and none were dissatisfied post-pilot. Only one physician (17%) was satisfied with EHR use pre-pilot, which increased to five (83%) post-pilot (Table 1).

Physician Attitudes Towards Working with Scribe

In general, attitudes towards working with the scribe were positive. All six physicians agreed that every physician should have the opportunity to work with a scribe and that having a scribe helped them focus better at work, made clinic less hectic, and improved workplace satisfaction. Five physicians (83%) agreed that having a scribe added value to their interactions with patients and decreased stress at work and at home. Four physicians (67%) agreed that having a scribe allowed them to better connect with patients.

Three physicians (50%) were interested in working with a scribe for all clinic sessions. Four (67%) were interested in working with a scribe even if they were working with medical students and were open to seeing one extra patient per session with a scribe. One physician (17%) thought the scribe was in the way and expressed concerns about patient privacy. None of the physicians expressed concerns about accuracy or timeliness of documentation when working with a scribe (Online Appendix 4).

In exit interviews, physicians reported positive feedback on the pilot. One physician stated: “You had me at the first visit…first time in 10 years I was able to truly focus on the patient without distraction by the EHR.” Others noted that they had “less sense of dread during busy clinics,” and it was “great to […] have my notes done so I could go home and have dinner with my family.” Some physicians suggested improvements, such as not having a scribe when working with medical students because there were “too many bodies in the room.”

Patient Satisfaction with Doctor–Patient Relationship

A total of 373 patients completed surveys; 48 (13%) were excluded due to incomplete data, and 325 were analyzed (166 scribed and 159 non-scribed visits) (Fig. 1). Sixty-nine percent of the patients were black, 65% female, and 48% were older than 65 years (Table 2).

Overall, patient satisfaction with the doctor–patient relationship was high. Over 80% strongly agreed that their doctor “explained things in a way that was easy to understand” and “spent enough time” with them; there was no difference based on whether a scribe was present or not (85 vs. 87 and 85 vs. 85%, respectively, p > 0.5). Over 75% of the patients strongly agreed that their physician’s computer use was not disruptive and that they were satisfied with physician computer use, with no difference based on whether a scribe was present or not (78 vs. 79 and 83 vs. 85%, respectively, p > 0.5). Similarly, there were no differences in responses to other patient satisfaction questions based on whether patients had a clinic visit with a scribe or not (p > 0.5), overall and by patient subgroups defined by age, gender, or race.

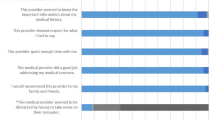

Patient Attitudes Towards Having a Scribe

In general, patients had neutral or positive attitudes about the scribe pilot. Ninety-two percent agreed that the scribe was courteous and respectful. About half (48%) agreed that their doctor should have a scribe. One third agreed that their physician “listened better,” “provided more education,” or was “more attentive” when the scribe was present compared to prior visits without a scribe present (38, 37, and 37%, respectively), while one fourth of patients gave a neutral response to those statements (24, 24, and 25%, respectively).

The majority of patients disagreed that the scribe was in the way, made them uncomfortable, or that they did not like having the scribe at their visit (88, 87, and 85%, respectively). A small number of patients (5%) asked the scribe to leave before the end of their visit.

Of the 107 responses to the open-ended question on the impact of the scribe on communication, most (69%) were neutral (e.g., “The scribe did not impact communication”). One quarter (24%) were positive (e.g., “Doctor spent more time talking instead of typing”), and 7% were negative (e.g., “Made me nervous”).

Of the 39 comments about the scribe pilot, most (67%) were positive (e.g., “The program is a good idea”). One quarter (23%) were neutral (e.g., “I did not mind the scribe”), and 10% were negative (e.g., “Do not like”). Interestingly, 13% of the patient comments expressed that if their doctors benefitted from the scribe, they were supportive (e.g., “If my doctor likes it, I am with it”).

There were some differences in attitudes towards having a scribe based on patient characteristics. Younger patients (18–64 vs. ≥ 65 years) were more likely to report that their physician “was more attentive” (46 vs. 28%) and provided more education (55 vs. 35%) during the visits when the scribe was present (p = 0.03 and 0.02, respectively). Male patients were more likely than female patients to report that they disliked having a scribe at their visit (55 vs. 36%) (p = 0.03) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

A scribe pilot was well received by faculty physicians and patients at an academic general internal medicine practice. Overall, the scribe pilot was associated with improved physician satisfaction with clinic workflow and EHR documentation, decreased stress at work and at home, and decreased post-visit documentation time by half.

Our findings of increased physician workplace satisfaction and decreased documentation burden are consistent with previous studies on outsourced scribe programs in primary care.19, 24 The majority of physicians in our pilot reported that working with a scribe allowed them to feel less rushed, decreased distraction from the EHR, and improved their ability to connect with patients. Our physician perceptions that the EHR distracts them from patients are not surprising, since time motion studies have found that half of physician clinic time is spent on EHR documentation.31 Interestingly, only one third of patients felt that physicians were more focused on them during scribed visits, suggesting that physicians perceive EHR use as a larger hindrance to patient–doctor communication than patients do, likely due to the cognitive burden of multitasking that EHRs require. Thus, working with scribes can be a solution to reduce physician multitasking, which potentially can reduce medical errors.32

Our physicians did not report increased stress when working with scribes, which contrasts with prior literature. A recent qualitative study found that physicians reported increased stress due to workflow changes when working with scribes who were MAs or nurses with expanded roles.27 The difference in results may reflect differences in the roles and expectations of scribes in the in-house trained vs. outsourced model. Further studies should look at the system-level, scribe, and physician factors that influence the workflow integration of scribes and the subsequent impact on team stress.

The impact of scribes on physician well-being and burnout is an important issue to explore. The high rates of burnout in primary care are concerning and can decrease quality of care.33 Prior studies found that EHR burden and a chaotic workplace environment contribute to physician dissatisfaction, and our findings suggest that a scribe program may be a promising intervention to address these issues.6 While we found no change in burnout using the single-item burnout question during our 3-month pilot, other studies have found a decrease in physician burnout using the more comprehensive Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) over longer study periods.16

Overall, we found high patient acceptance of the scribe pilot and the presence of a scribe did not negatively impact satisfaction regardless of the patient’s age, gender, and race. Among patients who had a scribe at their visit, the vast majority found the scribe to be courteous and respectful. Patient satisfaction remained at a high level and was unchanged with the scribe pilot. Likely due to ceiling effects, the presence of the scribe did not increase patient satisfaction with the doctor–patient relationship.

Importantly, our study is one of the first to explore patient attitudes towards scribes, while taking into account patient demographic characteristics. While race did not impact patient attitudes towards scribes, we found that older patients (≥ 65 years) were less likely than younger patients to report a positive impact of the scribe pilot. This may be due to older patients placing more value on the dyadic doctor–patient relationship and having more established relationships with physicians. Additionally, men disliked having the scribe at their visit more than women, which may be related to the gender discordance in having a 20 to 30-year-old female scribe in the room, which is consistent with prior research.27 However, despite these differences, the scribe did not impact overall patient satisfaction. Further research is needed to understand the impact of demographic characteristics of scribes on patient attitudes.

Our study evaluated the impact of an outsourced scribe model in an academic primary care setting. In clinical settings where existing staff (i.e., MAs and LPNs) may not have the capacity to expand their roles, an outsourced scribe program may provide a feasible alternative. Outsourcing the training and management of scribes to an outside company has been found to be cost-effective in subspecialty clinics and in a rural primary care clinic, due to increased number of patients seen with a scribe.14, 15, 24 Our physicians were open to seeing one extra patient per clinic session to offset the cost of employing a scribe; however, more research is needed on the cost-effectiveness of an outsourced scribe program in primary care.

Our study has several limitations. Our small physician sample size and the short duration of the pilot limited our ability to detect a change in burnout and longer term effects on physician and patient satisfaction. Our pilot included one 20 to 30-year-old female scribe, and we could not assess the impact of scribe characteristics, such as gender, race, or age. Our patient demographics (e.g., large percentage of African American patients) may also limit generalizability. To minimize survey burden, we used the single-item burnout question, which may have limited our ability to detect burnout. Moreover, physician time spent on documentation was assessed using self-report, which is subject to recall bias. Lastly, the patient survey was only available in English, and we missed perspectives of non-English speaking patients.

Our study found that outsourced scribes may offer a promising solution to improve academic primary care physician satisfaction without impacting patient satisfaction. The benefits for primary care physicians working with scribes may include reduction of EHR burden, reduced stress, and improvements in clinical workflow.

References

Heisey-Grove, D. and V. Patel (2015). ONC Data Brief: any, certified, and basic: quantifying physician EHR adoption through 2014. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.28:1–10. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/briefs/oncdatabrief28_certified_vs_basic.pdf .Accessed March 12, 2018.

Campanella P, Lovato E, Marone C, et al. The impact of electronic health records on healthcare quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health.2016;26(1):60–4.

Alkureishi MA, Lee WW, Lyons M, et al. Impact of electronic medical record use on the patient–doctor relationship and communication: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med.2016;31(5):548–60.

Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc.2014;21(e1):e100–6.

Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health Q. 2014;3(4).

Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med.2016;31 (9):1004–10.

Gregory ME, Russo E, Singh H. Electronic health record alert-related workload as a predictor of burnout in primary care physicians. Appl Clin Inform.2017;8(3):686–97.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc.2016; 91(7):836–48.

Crowson MG, Vail C, Eapen RJ. Influence of electronic medical record implementation on provider retirement at a major academic medical centre. J Eval Clin Pract.2016;22(2):222–6.

The Joint Commission. Human resources (HR) scribe—definition. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/jcfaqdetails.aspx?StandardsFAQId=1206&StandardsFAQChapterId=19&ProgramId=0&ChapterId=0&IsFeatured=False&IsNew=False&Keyword. Accessed March 12, 2018.

Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, Bananno D, Anderson W. An ED scribe program is able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med.2014;32(5):399–402.

Hess JJ, Wallenstein J, Ackerman JD, et al. Scribe impacts on physician experience, operations, and teaching in an academic emergency medicine practice. West J Emerg Med.2015;16(5):602–10.

Heaton HA, Nestler DM, Jones DD, et al. Impact of scribes on billed relative value units in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med.2017;52(3):370–6.

Bank AJ, Gage RM. Annual impact of scribes on physician productivity and revenue in a cardiology clinic. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res.2015;7:489–95.

Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, et al. Impact of scribes on patient interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a prospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res.2013;5:399–406.

Contratto E, Romp K, Estrada CA, Agne A, Willett LL. Physician order entry clerical support improves physician satisfaction and productivity. South Med J.2017;110(5):363–8.

Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, Kogan BA. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol.2010;184(1):258–62.

Shuaib W, Hilmi J, Caballero J, et al. Impact of a scribe program on patient throughput, physician productivity, and patient satisfaction in a community-based emergency department. Health Inform J.2017; Apr 1. [Epub ahead of print]

Imdieke BH, Martel ML. Integration of medical scribes in the primary care setting: improving satisfaction. J Ambul Care Manage.2017;40(1):17–25.

Shultz CG, Holmstrom HL. The use of medical scribes in health care settings: a systematic review and future directions. J Am Board Fam Med.2015;28(3):371–81.

Anderson P, Halley MD. A new approach to making your doctor-nurse team more productive. Fam Pract Manag.2008;15(7):35–40.

Woodcock DV, Pranaat R, McGrath K, Ash JS. The evolving role of medical scribe: variation and implications for organizational effectiveness and safety. Stud Health Technol Inform.2017;234:382–8.

Funk KA, Davis M. Enhancing the role of the nurse in primary care: the RN “co-visit” model. J Gen Intern Med.2015;30(12):1871–3.

Earls ST, Savageau JA, Begley S, Saver BG, Sullivan K, Chuman A. Can scribes boost FPs’ efficiency and job satisfaction? J Fam Pract.2017;66(4):206–14.

Reuben DB, Miller N, Glazier E, Koretz BK. Frontline account: physician partners: an antidote to the electronic health record. J Gen Intern Med.2016;31(8):961–3.

Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, Glazier E, Koretz BK. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med.2014;174(7):1190–3.

Yan C, Rose S, Rothberg MB, Mercer MB, Goodman K, Misra-Hebert AD. Physician, scribe, and patient perspectives on clinical scribes in primary care. J Gen Intern Med.2016;31(9):990–5.

Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med.2015;30(5):582–7.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Services. CAHPS Clinician & Group Survey. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/cg/index.html. Accessed March 12, 2018.

The University of Chicago Institute for Translational Medicine. REDCap Biomedical Informatics Services. Available at: http://itm.uchicago.edu/redcap-bioinformatics-services/. Accessed March 12, 2018.

Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Annals of Internal Medicine.2016;165(11):753.

Ratanawongsa N, Matta GY, Lyles CR, et al. Multitasking and silent electronic health record use in ambulatory visits. JAMA Intern Med.2017;177(9):1382–5.

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings.2015;90(12):1600–13.

Contributors

We acknowledge the following contributors: Lisa Vinci MD MS, Lynda Hale, Debra White.

Funding

We have received funding from the Bucksbaum Pilot Grant and the University of Chicago Section of General Internal Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Prior Presentations

The results of this pilot study have not been previously presented. This research was presented as posters at the SGIM 2018 National Meeting and the AAMC Integrating Quality 2018 meeting.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pozdnyakova, A., Laiteerapong, N., Volerman, A. et al. Impact of Medical Scribes on Physician and Patient Satisfaction in Primary Care. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1109–1115 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4434-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4434-6