Abstract

The fruit of Guamúchil is an excellent source of bioactive compounds for human health although their natural occurrence could be affected by the ripening process. The aim was to evaluate some physicochemical, chemical and antioxidant changes in guamúchil fruit during six ripening stages (I to VI). A defined trend (p ≤ 0.003) was observed for color [°Hue, 109 (light green) to 20 (dark red)], anthocyanins (+571 %), soluble solids (+0.33 oBrix), ash (+16 %), sucrose (−91 %), proanthocyanidins (63 %), ascorbic acid (−52 %) and hydrolysable PC (−21 %). Carotenoids were not detected and chlorogenic acid was the most abundant phenolic compound. Maximal availability of these bioactives per ripening stage (p ≤ 0.03) was as follows: I (protein/ lipids/ sucrose/ proanthocyanidins/ hydrolysable phenolics), II (total sugars/ascorbic acid), III (total phenolics), IV (flavonoids/ chlorogenic acid) and VI (fructose/ glucose/ anthocyanins). Color change was explained by sucrose (β = 0.47) and anthocyanin (β = 0.20) contents (p < 0.001). Radical scavenging capacity (ORAC, DPPH and TEAC) strongly correlated with total PC (r = 0.49–0.65, p ≤ 0.001) but 89 % of ORAC’s associated variance was explained by anthocyanin + sucrose + ascorbic acid (p ≤ 0.0001). Guamúchil fruit could be a more convenient source of specific bioactive compounds if harvested at different ripening stages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AAPH:

-

2,2'-azobis-2-amidinopropane

- ABTS▪ − :

-

2,2'-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate

- DPPH:

-

2-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl hydrate

- EN:

-

Essential nutrient

- ORAC:

-

Oxygen radical absorbance capacity

- PC:

-

Phenolic compounds

- PDf :

-

Pithecellobium dulce fruit

- RSC:

-

Radical scavenging capacity

- Trolox:

-

6-hydroxy.2.5.7.8-tetramethyl-s-dicarboxylic acid

- TE:

-

Trolox equivalents

References

Kubola J, Siriarmornpun S, Meeso N (2011) Phytochemicals, vitamin C and sugar content of Thai wild fruits. Food Chem 126:972–981

Rasingam L (2012). Ethnobotanical studies on the wild edible plants of Irula tribes of Pilur Valley, Coimbatore district, Tamil Nadu India. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2012: S1493–S1497

Pio-León JF, Díaz-Camacho SP, Montes-Ávila J, et al. (2013) Nutritional and nutraceutical characteristics of white and red Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth fruits. Fruits 68:397–408

Chaparro-Santiago A, Osuna-Fernández HR, Aguilón-Arenas J, et al. (2015) Nutritional composition of Pithecellobium dulce, Guamuchil aril. Pakistan. J Nutr 14(9):611–613

Rao GN, Nagender A, Satyanarayana A, et al. (2011) Preparation, chemical composition and storage studies of quamuchil (Pithecellobium dulce L.) aril powder. J Food Sci Technol 48(1):90–95

Mohamed AI, Rangappa M Screening soybean (grain and vegetable) genotypes for nutrients and anti-nutritional factors. Plant foods Hum Nutr 42(1):87–96

Mojica L, de Mejía EG (2015) Characterization and comparison of protein and peptide profiles and their biological activities of improved common bean cultivars (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) from Mexico and Brazil. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 70(2):105–112

Juárez-Vázquez MC, Carranza-Álvarez C, Alonso-Castro AJ, et al. (2013) Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used in Xalpatlahuac Guerrero, Mexico. J Ethnopharm 148:521–527

Nagmoti DM, Khatri DK, Juvekar PR, et al. (2012) Antioxidant activity and free-radical scavenging potential of Pithecellobium dulce Benth seed extracts. Free Rad Antiox 2(2):37–43

Katekhaye SD, Kale MS (2011) Antiopxidant and free radical scavenging activity of Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth wood bark and leaves. Free Rad Antiox 2(3):47–57

Megala J, Geetha A (2010) Free radical-scavenging and H+, K + −ATPase activities of Pithecellobium dulce. Food Chem 121:1120–1128

Megala J, Geetha A (2012) Antiulcerogenic activity of hydroalcoholic fruit extract of Pithecellobium dulce in different experimental ulcer models in rats. J Ethnopharm 142(2):415–421

Manna P, Bhattacharyya S, Das J et al (2011). Phytomedicinal role of Pithecellobium dulce against CCl4-mediated hepatic oxidative impairments and necrotic cell death. Ev Based Compl Altern Med 2011:1–17

Pal PB, Pal S, Manna P, et al. (2012) Traditional extract of Pithecellobium dulce fruits protects mice against CCl4 induced renal oxidative impairments and necrotic cell death. Pathophysiol 19:101–114

Palafox-Carlos H, Yahia E, Islas-Osuna MA, et al. (2012) Effect of ripeness stage of mango fruit (Mangifera indica L. cv. Ataulfo) on physiological parameters and antioxidant activity. Sci Hortic 135:7–13

Nsonzi F, Ramaswamy HS (1998) Quality evaluation of osmo-convective dried blueberries. Dry Technol 6:705–723

McLellan MR, Lind LR, Kime RW (1995) Hue angle determinations and statistical analysis multiquadrant hunter L, a, b data. J Food Quality 18(3):235–240

González-Aguilar GA, Celis J, Sotelo-Mundo RR, et al. (2008) Physiological and biochemical changes of different fresh cut mango cultivars stored at 5oC. Int J Food Sci Technol 43(1):91–101

Mejía LA, Hudson E, González de Mejía E, et al. (1988) Carotenoid content and vitamin a activity of some common cultivars of Mexican peppers (Capsicum annum) as determined by HPLC. J Food Sci 53:1448–1451

Donner LW, Hicks KB (1981) High-performance liquid chromatographic separation of ascorbic acid, erytrorbic acid, dehydroascorbic acid, dehydroerythorbic acid, dikelogulonic acid and dikelogluconic acid. Anal Biochem 115:225–230

Feregrino-Pérez AA, Torres-Pacheco I, Vargas-Hernández M, et al. (2011) Antioxidant and antimutagenic activities of Acacia pennatula pods. J Sci Ind Res India 70:859–864 http://nopr.niscair.res.in/handle/123456789/12681

Singleton VL, Rossi JA (1965) Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic 16(3):144–158 http://www.ajevonline.org/content/16/3/144

Kim DO, Jeong SW, Lee CY (2003) Antioxidant capacity of phenolic phytochemicals from various cultivars of plums. Food Chem 81(3):321–326

Reed J, McDowell RE, Van Soest PJ, et al. (1982) Condensed tannins: a factor limiting the use of cassava forage. J Sci Food Agric 33:213–220

Schofield P, Mbugua DM, Pell AN (2001) Analysis of condensed tannins: a review. Animal Feed Sci Technol 91(1–2):21–40

Hartzfeld PW, Forkner R, Hunter DM, et al. (2002) Determination of hydrolyzable tannins (gallotannins and ellagitanins) after reaction with potassium iodate. J Agric Food Chem 50:1785–1790

Lee J, Durst, RW, Wrolstad, RE (2005). Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J AOAC Int 88(5): 1269–1278. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.487.1462&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset CLWT (1995) Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci Technol 28(1):25–30

Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C (1999) Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med 26(9):1231–1237

Ou B, Hampsch-Woodill M, Prior RL (2001) Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. J Agric Food Chem 49:4619–4626

Nilakshi V, Gambhir V, Bhaskar VV (2011) HPTLC analysis of vitamin C from Pithecellobium dulce, benth (fabaceae. J Pharm Res 4(4):1197–1198 http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/74250428/hptlc-analysis-vitamin-c-from-pithecellobium-dulce-benth-fabaceae

Ong KW, Hsu A, Tan BKH (2013) Anti-diabetic and anti-lipidemic effects of chlorogenic acid are mediated by ampk activation. Biochem Pharmacol 85(9):1341–1351

Wan CW, Wong CNY, Pin WK, et al. (2013) Chlorogenic acid exhibits cholesterol lowering and fatty liver attenuating properties by up-regulating the gene expression of PPAR-α in hypercholesterolemic rats induced with a high-cholesterol diet. Phytother Res 27(4):545–551

López-Martínez LM, Santacruz-Ortega H, Navarro RE, et al. (2015) A 1H NMR investigation of the interaction between mango (Mangifera indica cv Ataulfo) and papaya (Carica papaya cv Maradol) and 1,1-diphenil-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radicals. PLos ONE 10(11):e0140242

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Arturo Velazquez-Salazar for providing PDf samples, to Dr. Fernando Ayala-Zavala for reviewing this manuscript and to all authorities from CIAD, UACJ and UAQ for their support during this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth fruit (PDf) during ripening. Left to right: stages I to III (up), stages IV to VI (down). JPEG file (JPEG 68 kb)

ESM 2

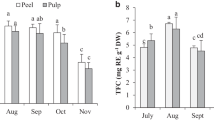

a. Physicochemical changes in PDf during ripening. JPEG file (JPEG 205 kb)

ESM 2

b (JPEG 183 kb)

ESM 3

Chemical changes in PDf during ripening. JPEG file (JPEG 274 kb)

ESM 4

Phenolic compounds changes in PDf during ripening. JPEG file (JPEG 324 kb)

ESM 5

Radical scavenging capacity (RSC) changes in PDf during ripening. JPEG file (JPEG 154 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wall-Medrano, A., González-Aguilar, G.A., Loarca-Piña, G.F. et al. Ripening of Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. [Guamúchil] Fruit: Physicochemical, Chemical and Antioxidant Changes. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 71, 396–401 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-016-0575-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-016-0575-0