Abstract

Purpose Three out of ten patients do not return to work after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Patient expectations are suggested to play a key role. What are patients’ expectations regarding the ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months after TKA compared to their preoperative status? Methods A multi-center cross-sectional study was performed among 292 working patients listed for TKA. The Work Osteoarthritis or joint-Replacement Questionnaire (WORQ, range 0–100, minimal important difference 13) was used to assess the preoperatively experienced and expected ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months postoperatively. Differences between the preoperative and expected WORQ scores were tested and the most difficult knee-demanding work-related activities were described. Results Two hundred thirty-six working patients (81%) completed the questionnaire. Patients’ expected WORQ score (Median = 75, IQR 60–86) was significantly (p < 0.01) higher than their preoperative WORQ score (Median = 44, IQR 35–56). A clinical improvement in ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities was expected by 72% of the patients, while 28% of the patients expected no clinical improvement or even worse ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months after TKA. Of the patients, 34% expected severe difficulty in kneeling, 30% in crouching and 17% in clambering 6 months after TKA. Conclusions Most patients have high expectations, especially regarding activities involving deep knee flexion. Remarkably, three out of ten patients expect no clinical improvement or even a worse ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months postoperatively compared to their preoperative status. Therefore, addressing patients expectations seems useful in order to assure realistic expectations regarding work activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Participating in work is an important treatment goal for a growing number of patients after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [1, 2]. The incidence of TKA is increasing in the Netherlands as well as in other Western countries [3,4,5,6]. This is also true in the working population, partly due to an increase in the age of retirement [7, 8] and partly due to TKA being performed more often at younger age [5, 9]. Surgeons have experienced difficulty in predicting functional outcomes also in the working TKA population [10]. Return to work (RTW) rates for this population vary between 68 and 85% [1, 11,12,13].

To ensure RTW for these patients, a better understanding of the barriers for RTW is needed. One of the barriers might be the ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities such as kneeling, crouching and clambering, which remain difficult after TKA [11]. The ability to perform other work-related activities, such as operating foot pedals and standing, improve more after TKA [11]. Moreover, it is possible that RTW might be facilitated not only by the ability to perform work-related activities after TKA, but also whether this ability is in line with the patients’ preoperative expectations [14] and the corresponding measures they take. Current evidence suggests that, in general, patients with higher recovery expectations are more likely to RTW than patients with lower recovery expectations [15]. The relevance of patient expectations to functional outcomes after TKA is agreed upon, although not yet clearly understood [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The largest percentages of unfulfilled expectations concern kneeling (47%), squatting (44%) and walking middle long-distance (40%) [17], which are also important work-related activities. However, other important work-related activities [22] such as lifting, working below knee-height and walking on rough terrain, are not described. Patient expectations regarding these work-related knee-demanding activities still require investigation.

Since patients of working age expect to perform better on a variety of work-related knee-demanding activities after TKA, and often at demanding levels [2], we want to quantify patient expectations regarding ability to perform such work-related knee-demanding activities. This might not only serve to improve preoperative understanding and advice [17], but might also support timely postoperative guidance and integrated care for patients [1, 13, 23, 24].

Therefore the research questions are:

-

(1)

What are patients’ expectations regarding the ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months after TKA compared to their preoperative status?

-

(2)

How many patients expect severe difficulty in the ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months after TKA compared to their preoperative status?

Patients and Methods

Multi-center Study

A multi-center cross-sectional observational study was performed among patients listed for TKA at seven hospitals in the Netherlands. The hospitals were selected based on existing collaborations with Amsterdam University Medical Centers and were located in the northern, central and southern part of the Netherlands including city and rural areas and serve general TKA populations. Recruitment took place between June 24, 2014 and November 10, 2016. The study is followed by a prospective cohort study on functional recovery and RTW after TKA.

In the Netherlands work status is not systematically registered by orthopedic surgeons so all patients between 18 and 65 years listed for TKA were selected at each hospital. All these patients received a written invitation to participate from the researchers, including information about the study and an informed consent form. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All patients who answered that they had a job and returned a signed informed consent form, before being operated, were included.

Preoperatively, the patients were asked to complete a questionnaire, either on paper or electronically, depending on their preference. A reminder to complete the questionnaire was sent after 2 weeks, up to two times, as long as they had not yet had their operation.

Work Osteoarthritis or Joint-Replacement Questionnaire (WORQ) and Expectations

The patients’ preoperatively experienced difficulty in performing work-related knee-demanding activities and their expectations for 6 months postoperatively were assessed by the Work Osteoarthritis or joint-Replacement Questionnaire (WORQ, Online Appendix, Table 1) [22, 25]. The expectations of the patients were asked in the following manner: How much difficulty do you expect performing these activities at work, 6 months after TKA surgery? The WORQ score consists of 13 items on work-related knee-demanding activities, like lifting and working below knee-height. These 13 activities are assessed on a 5-point scale, from 0 (extreme difficulty or unable to perform) to 4 (no difficulty at all), resulting in a converted total score between 0 (extreme difficulties) to 100 (no problems). A score of 71 or more is classified as being satisfied with their work ability with respect to the knee, while a score of 50 or less is considered as being unsatisfied [22]. The minimal clinically important difference (MID) of 13 points [22] was used to calculate how many patients expected a clinically relevant improvement in ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months postoperatively. The WORQ scores were dichotomized to determine how many patients experienced severe difficulty with each of the 13 items. “Severe difficulty” and “extreme/unable to perform” were classified as “severe difficulty”. “Moderate,” “mild” and “no” difficulty were classified as “no severe difficulty.” This was done for both the preoperative scores and the expected scores for 6 months after TKA.

Patient characteristics are described, such as age, sex, educational level, BMI, and comorbidity. Three Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) subscales were used as an indication of disease severity, KOOS symptoms (7 items), KOOS pain (9 items) and KOOS Quality of Life (4 items). All KOOS subscales ranged from extreme problems (0) to no problems (100) and are validated [26, 27]. The job of the patient was categorized as knee-demanding if the patient reported to perform ‘often’ or ‘always’ on one or more of the following five activities crouching, kneeling, clambering, taking the stairs or lifting [28, 29]. Patient characteristics were also described for patients with and without a knee-demanding job.

We limited the possibility of selection bias by including seven hospitals providing TKA surgery for city and rural regions across the Netherlands. Selection bias due to a lack of computer skills was prevented by offering a paper copy of the questionnaire [30]. By asking the preoperatively experienced difficulty in knee-demanding activities and expectations for 6 months postoperatively in the same questionnaire we have tried to overcome response bias. By first asking about their present preoperatively perceived difficulty and next about their expected difficulty 6 months postoperatively, we expected to obtain more reliable and realistic expectations.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the patient characteristics. Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test for categorical variables and Mann Whitney U test for continuous variables were used to test for statistical differences between patients with and without a knee demanding job.

For question 1, the preoperative and expected 6-months postoperative WORQ scores were calculated as well as the difference in scores. The Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to assess the statistical difference between the paired preoperative and expected 6-months postoperative WORQ scores. For question 2, the percentages of patients were calculated with “severe difficulty” preoperatively and expected “severe difficulty” postoperatively in performing a knee-demanding activity. McNemar’s test for paired samples was used to test for a difference between the pre- and postoperative “severe difficulty” scores.

Only participants with no missing data or a maximum of one missing item on the 13 items of the WORQ scores were included for analysis. In case of one missing item this was imputed corresponding to similar items belonging to knee coordination or strenuous knee flexion activities [22]. Sensitivity analysis was performed for expected WORQ scores and expected differences in WORQ scores in patients with and without a knee demanding job. Statistical difference between groups was tested using Mann Whitney U test for continuous variables and Pearson Chi square test for dichotomous variables.

The IBM SPSS version 22 was used for all statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Working TKA Patients—Characteristics

Of 801 patients on the waiting list for TKA who received information about the study, 461 patients did not have a job, did not respond in time to participate before surgery or did not respond at all (58%). Three hundred and forty (n = 340) patients agreed to participate but 48 of these patients did not meet the inclusion criteria of having a job (paid or voluntary). Therefore, 292 patients were eligible to participate in the study: 36% of all patients contacted (Fig. 1). By November 10, 2016, 236 of these 292 patients returned their questionnaires, and these were used in the analyses: 81% of all eligible patients willing to participate.

The demographics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The median age at the time of completing the questionnaire was 59 years (IQR 54–62 years), while 104 participants (44%) were male and 132 (56%) female. The median Body Mass Index (BMI = body mass/body height2) was 29 (IQR 26–33) and 80% (N = 187) of the patients did not have another impairing disease. The median of the KOOS subscale for symptoms was 43 (IQR 32–57), the mean for pain was 38 (SD 17) and the median for Quality of Life was 25 (IQR 13–38). The questionnaire was completed by 134 patients less than 4 weeks before their TKA (57%); by 33 patients (14%), 4–8 weeks before; by 19 patients (8%), 8–12 weeks before; and by 24 patients (10%) more than 12 weeks preoperatively. For 26 patients (11%), the date of surgery was unknown. Of the study population, 95% (N = 224) desired to return to their current job after surgery, 12 patients (5%) did not, while 118 patients (50%) had a knee-demanding job.

WORQ

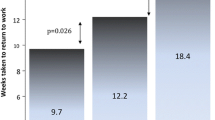

The median preoperative WORQ score was 44 [IQR 35–56]. In total, 66% of the patients (n = 156) reported a WORQ score of 50 or less, meaning an “unsatisfying” ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities (Fig. 2). The median expected WORQ score 6 months after TKA was 75 [IQR 60–85] and significantly higher compared to the preoperative score (p < 0.01). 6 Months after TKA, 143 patients (61%) expected a score of 71 or higher, meaning a “satisfying” ability to perform knee-demanding activities, and 41 patients (17%) expected a WORQ score of 50 or less, meaning an “unsatisfying” ability. The median intra-individual change in scores was 29 [IQR 10–44, range − 37 to 90]. Of the patients, 72% (n = 171) expected a WORQ score of at least 13 points (MID) higher than their preoperative score, meaning that they expected a clinically important improvement. Of the patients who expected no clinically important improvement (N = 65, 28%), 32 patients (14%) expected no improvement or even a deterioration in performance. Only 7 WORQ-items were imputed of a total of 3068 items for the WORQ and the expected WORQ score (0.2%). Sensitivity analysis revealed no statistically significant difference between expected WORQ score and expected difference in WORQ score for patients with and without a knee demanding job (Table 2).

Severe Difficulty in Activities

Preoperatively, the largest percentage of patients experienced severe difficulty with kneeling (84%), followed by crouching (78%) and clambering (65%) (Fig. 3). The percentage of patients expecting severe difficulty 6 months postoperatively was largest for kneeling (34%), crouching (30%) and clambering (17%). For all other work-related knee-demanding activities, 9–12% of the patients expected severe difficulty 6 months postoperatively. Fifty percent (− Δ50%) fewer patients expected to have severe difficulty with kneeling 6 months postoperatively compared to preoperatively, and 48% fewer for crouching and clambering. The same was true for taking the stairs (− Δ44%), working with hands below knee height (− Δ42%), standing (− Δ37%), lifting or carrying (− Δ33%), pushing or pulling (− Δ33%) and walking on level ground (− Δ19%). For these nine activities, patients have significantly (p < 0.01) higher expectations regarding the ability to perform them after TKA compared to their preoperatively experienced ability. Only 5% fewer patients expected severe difficulty operating a vehicle (p = 0.07), 4% (p = 0.26) foot pedals and 1% (p = 0.86) sitting after TKA.

Discussion

WORQ

Patients have high expectations of TKA regarding their ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months postoperatively. Their expected median WORQ score of 75 (IQR 60–86) was a little higher than the median WORQ score of 72 (IQR 54–83) 2 years after TKA, reported in a retrospective study among working-age Dutch TKA patients [11]. One out of four patients in our study expected a score above 86 and some even up to 100, with the latter meaning that they expect “no difficulties at all” in their ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months postoperatively. In the above-mentioned retrospective study [11], 9% of the patients (n = 10) had a WORQ score of 100, evidence that it is achievable.

Of our study population, 72% expected an improvement in work-related knee-demanding activities that would be of clinical importance. Therefore, the majority of working patients expect that TKA will improve their ability to perform at work. This is in line with percentages found in studies on RTW after TKA, varying between 68 and 85% [1, 11,12,13]. Remarkably, 28% expected no clinical improvement and no less than 14% of all patients expected no improvement at all or even a worse performance 6 months after TKA. One explanation for this might be that these patients have low expectations because they expect a vocational rehabilitation period of more than 6 months.

In studies of RTW after TKA, percentages between 17% [12] and 30–40% [11, 31] have been found for no RTW within 6 months, also indicating a prolonged rehabilitation period. An expected prolonged period of recovery might especially be likely for patients performing knee-demanding work or patients receiving no vocational rehabilitation or integrated work-directed care. Other explanations might be that these patients expect improvement on other dimensions such as pain or symptoms, instead of improvement in ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities. This is in line with the suggestion made by Haynes et al. [32] to inform patients (≤ 55 years) about not achieving substantially high levels of function after TKA, relative to their age and preoperative activity level.

If low expectations were influenced by having a knee-demanding job, we would have found differences in expected WORQ scores (Table 2). Instead of differences in outcome on WORQ scores, we found significant baseline differences for age and the subscale KOOS-pain (Table 1). We applied a sensitivity analyses for these baseline characteristics of the TKA patients by exploring the highest and lowest tertiles. Patients ≤ 55 year (n = 76, 32%) expected more improvement in WORQ score namely a median of 31 points [IQR 16–44] than patients ≥ 61 year (n = 88, 37%) who expected a median improvement of 23 points [IQR 8–38]. Patients reporting more pain (KOOS pain ≤ 29, n = 76, 32%) expected a median improvement in WORQ scores of 40 points [IQR 22–52] compared to 22 points [6–35] by patients reporting less pain (KOOS pain ≥ 46, n = 76, 32%). These findings highlight the importance of paying special attention to expected changes in the ability to perform work-related activities after TKA.

In all attempts to explain patients’ low expectations of their ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities, it is important to explore whether these expectations are proven true 6 months after TKA, including the impact on work participation. While patients with higher recovery expectations are, in general, more likely to RTW [15] it seems important to determine what factors influence low expectations and what factors might contribute to guiding these patients toward the most achievable goals regarding the ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities. The increasing number of working TKA patients in the upcoming decades, stresses the importance of managing low patient expectations in order to secure realistic expectations and hopefully thereby contributing to a timely and sustainable RTW of this patient group ‘at risk’.

Severe Difficulty in Activities

Most patients (88–91%) expected no severe difficulties for 10 of the 13 work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months after TKA. However, patients did expect severe difficulty in kneeling (34%), crouching (30%) and clambering (17%) 6 months postoperatively. These expectations are in line with preoperative information regarding functional limitations after TKA [33]. However, most of the patients in our study expected more improvement in activities involving deep knee flexion; namely, kneeling, crouching and clambering, than in activities involving knee coordination, such as operating foot pedals and walking, according to the classification of Kievit et al. [22]. This contrasts with previous research [11] in which activities involving knee coordination improved most and activities involving deep knee flexion had improved least 2 years after TKA in working patients of comparable age (mean 60 years) and BMI (mean 29.5). Moreover, in this retrospective study 2 years after surgery, higher percentages of patients having severe difficulty in kneeling, crouching and clambering were found; namely, 48%, 45% and 25%, respectively. Impairments involving knee flexion following TKA have also been found in patients younger than 60 and were highlighted in a review on establishing realistic patient expectations [20, 34]. Tilbury et al. [17] found the greatest proportions of unfulfilled expectations in the same activities; namely, kneeling and squatting. Better insight into the effects of expectations and what is achievable with respect to performing work-related knee-demanding activities is needed to guide patients and health care professionals in setting high and achievable goals [16]. Based on our findings, it is possible that expectations about the ability to perform deep knee flexion activities are too high. For this, a follow-up study is required to assess what the actual WORQ outcomes are 6 months after surgery. The effectiveness of expectation modification in case of over-optimistic expectations for TKA surgery also requires more corresponding evidence [35].

Moreover, it seems important to assess whether setting achievable goals preoperatively [36] is helpful in attaining better individualized functional recovery and more satisfied patients postoperatively. Patients who have low expectations of their postoperative ability to perform knee demanding activities might thereby foresee a discrepancy between their ability and the required work demands. In that case, the possibilities of workplace adaptations to overcome their needs (adjustment latitude [37]) are of primary importance including support by their employer, co-workers and of course the occupational health experts involved. In general, patients with end-stage knee osteoarthritis are recommended to postpone surgery if possible by using effective non-operative treatment like losing body weight, exercising, and using pain medication to avoid complications due to surgery among other reasons [38, 39].

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study are the large sample size and high response rate of eligible patients willing to participate, the preoperative assessment of patient expectations and the specific data on expectations for work-related knee-demanding activities. Another strength is the inclusion of patients with and without knee demanding work which makes it possible to explore expectations for the distribution of knee demands at work. The classification of performing knee demanding activities at work was based on the self-reports of the patients whether their work involved ‘often’ or ‘always’ crouching, kneeling, clambering, taking the stairs or lifting, thereby taking into account established risk factors for knee osteoarthritis [29].

A limitation of our study is that we do not know why the contacted 461 patients did not participate. For instance, did they not have a job, did they not want to participate, or did they have too little time to fill in the questionnaire before surgery? Another limitation might be a selection bias for patients fluent in reading and writing, so we might have included less lowly educated patients than in the general working population. The educational level of our sample was lower than the general Dutch working population between 55 and 65 (11%, 61%, 28%, respectively) but in line with the working TKA population described in another Dutch multicenter study by Leichtenberg (low 29%, medium 45%, high 27%) [13, 40]. This might indicate that we included comparable numbers of low, medium and higher educated patients. The results of this multi-center study seem generalizable to Dutch working TKA patients registered in other hospitals in the Netherlands then the hospitals participating in this study, given the similarities in age, sex, educational level and disease severity [13].

Another limitation might concern the fact that the WORQ does not specify the exposure to work-related knee-demanding activities of each patient in terms of level, frequency or duration. However, asking about this exposure in more detail would probably not have resulted in more accurate answers, given findings that suggest that patients do not answer these types of questions reliably [41, 42]. We expect that the influence of a difference in time point while filling in the questionnaire before surgery is small because the majority of patients (71%) completed the questionnaire within 8 weeks before surgery and this is a relatively short time period compared to the long period that these knee osteoarthritis patients suffer from the complaints before being admitted to have surgery.

Conclusions

In conclusion, seven out of ten patients have high expectations about their ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months after TKA, especially regarding activities involving deep knee flexion. Remarkably, 28% of patients expected no clinical improvement, no improvement at all or even a deterioration of ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities 6 months postoperatively compared to preoperatively. These results emphasize the importance of discussing these expectations pre- and postoperatively, so that health care professionals can timely advise patients on whether additional care is needed after TKA.

References

Sankar A, Davis AM, Palaganas MP, Beaton DE, Badley EM, Gignac MA. Return to work and workplace activity limitations following total hip or knee replacement. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(10):1485–1493.

Witjes S, van Geenen RC, Koenraadt KL, van der Hart CP, Blankevoort L, Kerkhoffs GM, et al. Expectations of younger patients concerning activities after knee arthroplasty: are we asking the right questions? Qual Life Res. 2017;26(2):403–417.

Culliford D, Maskell J, Judge A, Cooper C, Prieto-Alhambra D, Arden NK, et al. Future projections of total hip and knee arthroplasty in the UK: results from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(4):594–600.

Weinstein AM, Rome BN, Reichmann WM, Collins JE, Burbine SA, Thornhill TS, et al. Estimating the burden of total knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(5):385–392.

Wengler A, Nimptsch U, Mansky T. Hip and knee replacement in Germany and the USA: analysis of individual inpatient data from German and US hospitals for the years 2005 to 2011. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(23–24):407–416.

Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624–630.

Trends in Nederland. Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2016. https://www.cbs.nl/-/media/_pdf/2016/26/2016-trends-in-nederland-2016.pdf. Accessed 01 June 2016.

Statline CBS. Statline CBS age of retirement NL 2000. 2016. http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=80396NED&D1=9&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=1&D6=0-1. Accessed 20 June 2017.

Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Zhao K, Kelly M, Bozic KJ. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(10):2606–2612.

Ghomrawi HMK, Mancuso CA, Dunning A, Della Valle AG, Alexiades M, Cornell C, et al. Do surgeon expectations predict clinically important improvements in WOMAC scores after THA and TKA? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(9):2150–2158.

Kievit AJ, van Geenen RC, Kuijer PP, Pahlplatz TM, Blankevoort L, Schafroth MU. Total knee arthroplasty and the unforeseen impact on return to work: a cross-sectional multicenter survey. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(6):1163–1168.

Tilbury C, Schaasberg W, Plevier JW, Fiocco M, Nelissen RG, Vliet Vlieland TP. Return to work after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2014;53(3):512–525.

Leichtenberg CS, Tilbury C, Kuijer P, Verdegaal S, Wolterbeek R, Nelissen R, et al. Determinants of return to work 12 months after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98(6):387–395.

Hoorntje A, Leichtenberg CS, Koenraadt KLM, van Geenen RCI, Kerkhoffs G, Nelissen R, et al. Not physical activity, but patient beliefs and expectations are associated with return to work after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2018;33(4):1094–1100.

Ebrahim S, Malachowski C, El Din MK, Mulla SM, Montoya L, Bance S, et al. Measures of patients’ expectations about recovery: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):240–255.

Jain D, Nguyen LL, Bendich I, Nguyen LL, Lewis CG, Huddleston JI, et al. Higher patient expectations predict higher patient-reported outcomes, but not satisfaction, in total knee arthroplasty patients: a prospective multicenter study. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(9S):S166–S170.

Tilbury C, Haanstra TM, Leichtenberg CS, Verdegaal SH, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, et al. Unfulfilled expectations after total hip and knee arthroplasty surgery: there is a need for better preoperative patient information and education. J Arthroplast. 2016;31(10):2139–2145.

Haanstra TM, van den Berg T, Ostelo RW, Poolman RW, Jansma EP, Cuijpers P, et al. Systematic review: do patient expectations influence treatment outcomes in total knee and total hip arthroplasty? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):152–165.

Gonzalez Saenz de Tejada M, Escobar A, Bilbao A, Herrera-Espineira C, Garcia-Perez L, Aizpuru F, et al. A prospective study of the association of patient expectations with changes in health-related quality of life outcomes, following total joint replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15(1):248–257.

Husain A, Lee GC. Establishing realistic patient expectations following total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(12):707–713.

Escobar A, Garcia Perez L, Herrera-Espineira C, Aizpuru F, Sarasqueta C, Gonzalez Saenz de Tejada M, et al. Total knee replacement: are there any baseline factors that have influence in patient reported outcomes? J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(6):1232–1239.

Kievit AJ, Kuijer PP, Kievit RA, Sierevelt IN, Blankevoort L, Frings-Dresen MH. A reliable, valid and responsive questionnaire to score the impact of knee complaints on work following total knee arthroplasty: the WORQ. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(6):1169–1175

Kuijer PP, Kievit AJ, Pahlplatz TM, Hooiveld T, Hoozemans MJ, Blankevoort L, et al. Which patients do not return to work after total knee arthroplasty? Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(9):1249–1254.

Styron JF, Barsoum WK, Smyth KA, Singer ME. Preoperative predictors of returning to work following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(1):2–10.

Gagnier JJ, Mullins M, Huang H, Marinac-Dabic D, Ghambaryan A, Eloff B, et al. A systematic review of measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures used in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(5):1688–1697

KOOS. 2012. http://www.koos.nu. Accessed 01 Aug 2012 [updated 01 Aug 2012]

Collins NJ, Roos EM. Patient-reported outcomes for total hip and knee arthroplasty: commonly used instruments and attributes of a “good” measure. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(3):367–394.

Palmer KT. Occupational activities and osteoarthritis of the knee. Br Med Bull. 2012;102(1):147–170.

Verbeek J, Mischke C, Robinson R, Ijaz S, Kuijer P, Kievit A, et al. Occupational exposure to knee loading and the risk of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Saf Health Work. 2017;8(2):130–142.

Keurentjes JC, Fiocco M, So-Osman C, Ostenk R, Koopman-Van Gemert AW, Poll RG, et al. Hip and knee replacement patients prefer pen-and-paper questionnaires: implications for future patient-reported outcome measure studies. Bone Joint Res. 2013;2(11):238–244.

Stigmar K, Dahlberg LE, Zhou C, Jacobson Lidgren H, Petersson IF, Englund M. Sick leave in Sweden before and after total joint replacement in hip and knee osteoarthritis patients. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(2):152–157.

Haynes J, Sassoon A, Nam D, Schultz L, Keeney J. Younger patients have less severe radiographic disease and lower reported outcome scores than older patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2017;24(3):663–669.

Orthopedic guideline TKP. Patient information: what is possible with a TKP. 2012. http://www.zorgvoorbeweging.nl/de-knieprothese#Mogelijk?. Accessed 20 June 2017.

Parvizi J, Nunley RM, Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr, Ruh EL, Clohisy JC, et al. High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(1):133–137.

Tolk JJ, Janssen RPA, Haanstra TM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Reijman M. The EKSPECT study: the influence of Expectation modification in Knee arthroplasty on Satisfaction of PatiEnts: study protocol for a randomized Controlled Trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):437–446.

Witjes S, Hoorntje A, Kuijer PP, Koenraadt KL, Blankevoort L, Kerkhoffs GM, et al. Does Goal Attainment Scaling improve satisfaction regarding performance of activities of younger knee arthroplasty patients? Study protocol of the randomized controlled ACTION trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):113–121.

Hultin H, Hallqvist J, Alexanderson K, Johansson G, Lindholm C, Lundberg I, et al. Low level of adjustment latitude—a risk factor for sickness absence. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(6):682–688.

Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, Rathleff MS, Arendt-Nielsen L, Simonsen O, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1597–1606.

Smink AJ, van den Ende CH, Vliet Vlieland TP, Swierstra BA, Kortland JH, Bijlsma JW, et al. “Beating osteoARThritis”: development of a stepped care strategy to optimize utilization and timing of non-surgical treatment modalities for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(12):1623–1629.

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Statline Educational level 55–65 year of age 2016 Q4. 2016. http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=82275NED&D1=0&D2=0&D3=6&D4=0-1%2c4-5&D5=0%2c2-4%2c8-10%2c12-14&D6=65-68%2cl&VW=T. Accessed 20 July 2017.

Burdorf A, van der Beek AJ. In musculoskeletal epidemiology are we asking the unanswerable in questionnaires on physical load? Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25(2):81–83.

van der Beek AJ, Frings-Dresen MH. Assessment of mechanical exposure in ergonomic epidemiology. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55(5):291–299.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gaby Moerlands-Berson from Amphia Hospital and all other research assistants for their help in conducting this study.

Funding

Paul Kuijer received personal funding from the Dutch Orthopaedic Society: Stichting Anna Fonds, Nederlands Orthopedisch Research en Educatie Fonds (NOREF) (Reference Number O201523).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Yvonne van Zaanen, Rutger C. I. van Geenen, Thijs M. J. Pahlplatz, Arthur J. Kievit, Marco J. M. Hoozemans, Eric W. P. Bakker, Matthias U. Schafroth, Daniel Haverkamp, Ton M. J. S. Vervest, Dirk H. P. W. Das, Vanessa A. Scholtes and Monique H. W. Frings-Dresen declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Leendert Blankevoort reports grants from Zimmer Biomet, outside the submitted work; Walter van der Weegen reports grants from ZimmerBiomet, grants from Cotera Inc, outside the submitted work; P. Paul F. M. Kuijer reports personal fees from Annafonds | NOREF (research fund Dutch Orthopaedic Society), during the conduct of the study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van Zaanen, Y., van Geenen, R.C.I., Pahlplatz, T.M.J. et al. Three Out of Ten Working Patients Expect No Clinical Improvement of Their Ability to Perform Work-Related Knee-Demanding Activities After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Multicenter Study. J Occup Rehabil 29, 585–594 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9823-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9823-5