Abstract

This paper examines the determinants of inter vivos (lifetime) transfers of ownership in German family firms between 2000 and 2013. Survey evidence indicates that owners of firms with strong current business conditions transfer ownership at higher rates than others. When a firm’s self-described business condition improves from “normal” to “good,” the relative likelihood of an inter vivos transfer increases by 46 percent. Inter vivos transfer rates also rose following a 2009 reform that reduced transfer taxes. These patterns suggest that transfer taxes significantly influence rates and timing of inter vivos ownership transfers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Schinke (2016) on how the tax reform influenced inter vivos transfers to different types of recipients including the core family, other close relatives, and unrelated recipients.

On inheritance and inter vivos transfer taxation and legislation see, e.g., Gale et al. (2001), Ellul et al. (2010), Hines (2010, 2013), Kopczuk (2009, 2013a, b) and Wrede (2014). Transfer taxes may give rise to declines in investment, slow sales growth, and a depletion of cash reserves around family successions (Tsoutsoura 2015).

See § 201 subsection two of the valuation law (Bewertungsgesetz).

On theoretical models of intergenerational private exchanges within the family under alternative assumptions as to the nature of relations between parents and children, see Cremer et al. (1992).

A firm is defined as a family firm if most voting capital is held by one or several interconnected families.

See Seiler (2010) on nonresponse in business surveys.

The survey questions are “Have there been inter vivos transfers of assets in your firm since the year 2000? Yes, in the year…/no,” and “Have you paid the gift tax since the year 2000? Yes, in the year …/no”.

The survey statement is “We evaluate our present state of business as good/satisfactory/bad.” The simplicity of this survey question makes it easily understood by potential respondents, and contributes to the high response rate. Complete questionnaires are available at https://doi.org/10.7805/ebdc-bep-2012.

See Seiler (2012) for more information.

Given asymmetries in reporting, it is likely that even fewer transfers would have been recorded if the survey instead asked beneficiaries about receipts of transferred business assets (Gale and Scholz 1994).

13 percent of inter vivos transfers were accompanied by a tax payment in the same year or during the following three years (see Table 1).

Replacing the current state of business variable with 0–1 dummies for either good or bad business conditions (two separate specifications) and replacing the number of employees variable by dummy variables for each category of number of employees produces results very similar to those reported in Table 3, as does estimation of standard errors in the Table 3 baseline regressions using bootstrap and jackknife procedures or using standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity and clustered at the individual level [Huber/White/sandwich standard errors—see Huber (1967) and White (1980)]. Limiting the sample to firms with fewer than 1,000 employees likewise has little effect on the results reported in Table 3.

Firm size is correlated with industry and legal form: firms in the retail and the services industries have, on average, fewer employees than firms in the construction and manufacturing industries, and firms operating as proprietorships have, on average, fewer employees than firms operating as corporations or partnerships.

References

Abberger, K., Birnbrich, M., & Seiler, C. (2009). Der Test des Tests im Handel—eine Metaumfrage zum ifo Konjunkturtest. ifo Schnelldienst 62, (pp. 34–41).

Ameriks, J., Caplin, A., Laufer, S., & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2011). The joy of giving or assisted living? Using strategic surveys to separate public care aversion from bequest motives. Journal of Finance, 66, 519–561.

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. Journal of Finance, 58, 1301–1328.

Arrondel, L., & Laferrère, A. (2001). Taxation and wealth transmission in France. Journal of Public Economics, 79, 3–33.

Arrondel, L., & Masson, A. (2006). Altruism, exchange or indirect reciprocity: What do the data on family transfers show? In S. Kolm & M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving: Altruism and reciprocity (pp. 971–1048). North Holland.

Astrachan, J. H., & Tutterow, R. (1996). The effect of estate taxes on family business: Survey results. Family Business Review, 9, 303–314.

Bennedsen, M., Meisner Nielsen, K., Perez-Gonzalez, F., & Wolfenzon, D. (2007). Inside the family firm: The role of families in succession decisions and performance. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122, 647–691.

Bernheim, B. D., Lemke, R. J., & Scholz, J. K. (2004). Do estate and gift taxes affect the timing of private transfers? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2617–2634.

Bertrand, M., Johnson, S., Samphantharak, K., & Schoar, A. (2008). Mixing family with business: A study of Thai business groups and the families behind them. Journal of Financial Economics, 88, 466–498.

Bjuggren, P., & Sund, L. (2001). Strategic decision making in intergenerational successions of small and medium-size family-owned businesses. Family Business Review, 14, 11–23.

Bjuggren, P., & Sund, L. (2005). Organization of transfers of small and medium-sized enterprises within the family: Tax law considerations. Family Business Review, 18, 305–319.

Brunetti, M. J. (2006). The estate tax and the demise of the family business. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 1975–1993.

Burkart, M., Panunzi, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Family firms. Journal of Finance, 58, 2167–2201.

Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saà-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource- and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14, 37–48.

Caillaud, B., & Cohen, D. (2000). Inter-generational transfers and common values in a society. European Economic Review, 44, 1091–1103.

Chen, S., Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Shevlin, T. (2010). Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms? Journal of Financial Economics, 95, 41–61.

Cremer, H., Kessler, D., & Pestieau, P. (1992). Intergenerational transfers within the family. European Economic Review, 36, 1–16.

De Massis, A., Chua, J. H., & Chrisman, J. J. (2008). Factors preventing intra-family succession. Family Business Review, 21, 183–199.

DeTienne, D. R., & Chrico, F. (2013). Exit strategies in family firms: How socioemotional wealth drives the threshold of performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31, 829–851.

Ellul, A., Pagano, M., & Panunzi, F. (2010). Inheritance law and investment in family firms. American Economic Review, 100, 2414–2450.

Faccio, M., & Lang, L. (2002). The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65, 365–395.

Gale, W. G., Hines, J. R., Jr., & Slemrod, J. (2001). Rethinking Estate and Gift Taxation. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Gale, W. G., & Scholz, J. K. (1994). Intergenerational transfers and the accumulation of wealth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8, 145–160.

Grossmann, V., & Strulik, H. (2010). Should continued family firms face lower taxes than other estates? Journal of Public Economics, 94, 87–101.

Guiso, L., & Jappelli, T. (1991). Intergenerational transfers and capital market imperfections. European Economic Review, 35, 103–120.

Hines, J. R., Jr. (2009). Taxing inheritances, taxing estates. Tax Law Review, 63, 189–207.

Hines, J. R., Jr. (2013). Income and substitution effects of estate taxation. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 103, 484–488.

Holtz-Eakin, D., Phillips, J. W. R., & Rosen, H. S. (2001). Estate taxes, life insurance, and small business. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83, 52–63.

Hönig, A. (2009). The new EBDC dataset: An innovative combination of survey and financial statement data. CESifo Forum, 10, 62–63.

Hönig, A. (2010). Linkage of Ifo survey and balance-sheet data: the EBDC business expectations panel & the EBDC business investment panel. Schmollers Jahrbuch—Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 130, 635–642.

Hönig, A. (2012). Financing restrictions revisited—is there a role for taxation and internal funds? Unpublished working paper. University of Nuremberg, Nuremberg.

Houben, H., & Maiterth, R. (2011). Endangering of businesses by the German inheritance tax? An empirical analysis. Business Research, 4, 32–46.

Hrung, W. B. (2004). Parental net wealth and personal consumption. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 54, 551–560.

Huber, P. J. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, (pp. 221–233).

Jacquemin, A., & de Ghellinck, E. (1980). Familial control, size and performance in the largest French firms. European Economic Review, 13, 81–91.

Joulfaian, D. (2004). Gift taxes and lifetime transfers: Time series evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1917–1929.

Joulfaian, D. (2005). Choosing between gifts and bequests: How taxes affect the timing of wealth transfers. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 2069–2091.

Joulfaian, D., & McGarry, K. (2004). Estate and gift tax incentives and inter vivos giving. National Tax Journal, 57, 429–444.

Kanniainen, V., & Poutvaara, P. (2007). Imperfect transmission of tacit knowledge and other barriers to entrepreneurship. Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, 28, 675–694.

Kopczuk, W. (2007). Bequest and tax planning: evidence from estate tax returns. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122, 1801–1854.

Kopczuk, W. (2009). Economics of estate taxation: A brief review of theory and evidence. Tax Law Review, 63, 139–157.

Kopczuk, W. (2013a). Incentive effects of inheritances and optimal estate taxation. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 103, 472–477.

Kopczuk, W. (2013b). Taxation of intergenerational transfers and wealth. In A. J. Auerbach, R. Chetty, M. Feldstein, & E. Saez (Eds.), Handbook of public economics Vol. 5, (pp. 329–390). North-Holland.

Kotlikoff, L. J. (1988). Intergenerational transfers and savings. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2, 41–58.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54, 471–517.

Laitner, J., & Ohlsson, H. (2001). Bequest motives: A comparison of Sweden and the United States. Journal of Public Economics, 79, 205–236.

Leland, H. E., & Pyle, D. H. (1977). Informational asymmetries, financial structure, and financial intermediation. Journal of Finance, 32, 371–387.

McConaughy, D. L., Walker, M. C., Henderson, G. V., Jr., & Mishra, C. S. (1998). Founding family controlled firms: Efficiency and value. Review of Financial Economics, 7, 1–19.

McGarry, K. (1999). Inter vivos transfers and intended bequests. Journal of Public Economics, 73, 321–351.

McGarry, K. (2001). The cost of equality: Unequal bequests and tax avoidance. Journal of Public Economics, 79, 179–204.

McGarry, K. (2013). The estate tax and inter vivos transfers over time. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 103, 478–483.

McGarry, K. (2016). Dynamic altruism: Inter vivos transfers from parents to children. Journal of Public Economics, 137, 1–13.

Miller, M. H., & Rock, K. (1985). Dividend policy under asymmetric information. Journal of Finance, 40, 1031–1051.

Minetti, R., Murro, P., & Zhu, S. C. (2015). Family firms, corporate governance and export. Economica, 82, 1177–1216.

Modigliani, F. (1988). The role of intergenerational transfers and life cycle saving in the accumulation of wealth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2, 15–40.

Molly, V., Laveren, E., & Deloof, M. (2010). Family business succession and its impact on financial structure and performance. Family Business Review, 23, 131–147.

Mullins, W., & Schoar, A. (2016). How do CEOs see their roles? Management philosophies and styles in family and non-family firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 119, 24–43.

Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13, 187–221.

Pérez-González, F. (2006). Inherited control and firm performance. American Economic Review, 96, 1559–1588.

Poterba, J. (2001). Estate and gift taxes and incentives for inter vivos giving in the US. Journal of Public Economics, 79, 237–264.

Schinke, C. (2016). Inter vivos transfers and the 2009 German transfer tax reform. Unpublished working paper. Ifo Institute, Munich.

Seiler, C. (2010). Dynamic modelling of nonresponse in business surveys. Ifo Working Paper No. 93.

Seiler, C. (2012). The data sets of the LMU-ifo economics & business data center—a guide for researchers. Schmollers Jahrbuch—Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 132, 609–618.

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., & Chua, J. H. (1997). Strategic management of the family business: Past research and future challenges. Family Business Review, 10, 1–35.

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., & Chua, J. H. (2003). Succession planning as planned behavior: Some empirical results. Family Business Review, 16, 1–15.

Stark, O., & Nicinska, A. (2015). How inheriting affects bequest plans. Economica, 82, 1126–1152.

Stark, O., & Zhang, J. (2002). Counter-compensatory inter-vivos transfers and parental altruism: Compatibility or orthogonality? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 47, 19–25.

Stavrou, E. T. (1999). Succession in family businesses: Exploring the effects of demographic factors on offspring intentions to join and take over the business. Journal of Small Business Management, 37, 43–61.

Tsoutsoura, M. (2015). The effect of succession taxes on family firm investment: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Finance, 70, 649–688.

Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80, 385–417.

Villanueva, E. (2005). Inter vivos transfers and bequests in three OECD countries. Economic Policy, 20, 505–565.

Vozikis, G. S., Liguori, E. W., Gibson, B., & Weaver, K. M. (2012). Reducing the hindering forces in intra-family business succession. American Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 4, 94–104.

Wennberg, K., & DeTienne, D. R. (2014). What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. International Small Business Journal, 32, 4–16.

Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., Hellersted, K., & Nordqvist, M. (2011). Implications of intra-family and external ownership transfer of family firms: Short-term and long-term performance differences. Strategic Entrepreneuership Journal, 5, 352–372.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–838.

Wrede, M. (2014). Fair inheritance taxation in the presence of tax planning. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 51, 12–18.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Editor and two anonymous referees for many helpful comments and suggestions that are incorporated in the paper. We would also like to thank Sebastian Escobar, Ben Lockwood, Liya Palagashvili, Dirk Schindler, Thomas Stratmann, Agnes Strauss, the participants of German Economic Association (Augsburg 2016), the CESifo Public Sector Economics conference (Munich 2016), European Association of Law and Economics (Vienna 2015), Congress of the International Institute of Public Finance (Dublin 2015) and Public Choice Society Meetings (San Antonio 2015), and seminars at the ifo Institute, Paris School of Economics, University of Michigan, Swiss Economic Institute at the ETH Zurich, Centre for Business Taxation at Oxford University, University of Bayreuth, and University of Munich for their helpful comments. We are grateful to the Foundation of Family Businesses, on whose behalf we conducted a survey on inheritances, inter vivos transfers, and transfer taxation (the Inheritance and Gift Tax Survey–IGTS) among owners of family firms in February and March 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

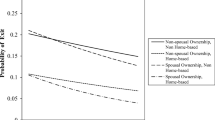

Because the study relies on survey data, response behavior may raise sample selection issues. Firms making inter vivos transfers could be overrepresented in the sample since the topic of the questionnaire is inheritance, inter vivos gifts, and their taxation. Firms unfamiliar with the inheritance and gift tax law because they did not experience a succession or did not make inter vivos transfers may have been less likely to participate because they did not think they had anything to contribute to the survey. Appendix Table 7 compares family firms responding to the IGTS to firms not responding. T tests reported in Appendix Table 7 indicate that the means of credit conditions and firm age are not statistically different in the two subsamples. Firms responding to the survey had a somewhat worse current state of business and expected development of employment than firms not responding (2.07 and 2.10; 1.98 and 2.00). Firms responding to the survey tend to be somewhat smaller than non-response firms as measured by log total assets and log total equity (14.58 and 14.87; 13.12 and 13.41). A Chi-squared test does not reject the null hypothesis that response behavior is independent of the federal state within Germany (P value of 0.51, see Fig. 5), but Chi-squared tests indicate that response behavior varies with numbers of employees, industry, and legal form. Firms responding to the survey tend to have fewer employees than firms choosing not to respond.Footnote 20 The results of the Chi-squared tests and t tests notwithstanding, there is little evidence that sample selection is an important issue in interpreting the results, since differences between the subsamples are small and the categorical variables assume multiple values in both of the subsamples. Furthermore, there is little reason to expect self-classification as a family firm in the Ifo Business Climate Survey to be prone to sample selection, since firms answered this question prior to learning the topic of the IGTS.

See Fig. 6.

Response rates and firm characteristics. Note The figure presents distributions of IGTS survey respondents and non-respondents by size (numbers of employees), federal state within Germany, industry, and legal form of operation. The figures display results of a Pearson Chi-squared test that response behavior is independent of numbers of employees/federal state/industry/legal form

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hines, J.R., Potrafke, N., Riem, M. et al. Inter vivos transfers of ownership in family firms. Int Tax Public Finance 26, 225–256 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-018-9508-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-018-9508-1