Abstract

Pork-barrel spending is the appropriation of federal money for use in projects that only benefit narrowly defined groups. In the past, researchers have attempted to show that pork-barrel spending increases the likelihood of an incumbent being reelected but empirical evidence has been hard to find. I hypothesize that pork-barrel spending does not directly increase the likelihood of reelection; instead, pork-barrel spending can be used to increase fundraising and the additional campaign funds are then used to increase the likelihood of being reelected. I find that a $10 million increase in pork-barrel spending will lead to a 0.10% increase in the share of the vote in an election. While this may not seem like a major advantage to some, several elections over the past few years have been decided by < 1%. Therefore, legislators in tightly contested races may be able to use pork-barrel spending to gain some degree of separation from their challenger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Erikson 1971, Erikson 1972, Mayhew 1974, Ferejohn 1977, Fiorina 1977, Born 1979, Collie 1981, Krehbiel and Wright 1983, Garand and Gross 1984, Cain et al. 1987, Jacobson 1987, Gelman and King 1990, Jacobson 1990, King and Gelman 1991, Cox and Katz 1996, Levitt and Wolfram 1997, Ansolabehere and Synder 2000.

This fact is also why a probit model cannot be used.

This is the only year of appropriation that ever had any statistical significance.

References

Abrams, B. A., & Settle, R. F. (2004). Campaign-finance reform: A public choice perspective. Public Choice, 120(3–4), 379–400.

Ansolabehere, S., & Snyder, J. M. (2000). Valence politics and equilibrium in spatial election models. Public Choice, 103(3–4), 327–336.

Ban-Zion, U., & Eytan, Z. (1975). On money, votes and policy in a democratic society. Public Choice, 17, 1–10.

Bickers, K. N., & Stein, R. M. (1996). The electoral dynamics of the federal pork barrel. American Journal of Political Science, 27-40.

Bonneau, C. W. (2007). Campaign fundraising in state supreme court elections. Social Science Quarterly, 88(1), 68–85.

Born, R. (1979). Generational replacement and the growth of incumbent reelection margins in the U.S. house. American Political Science Review, 73(03), 811–817.

Cain, B., Ferejohn, J., & Fiorina, M. (1987). The personal vote: Constituency service and electoral independence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Collie, M. P. (1981). Incumbency, electoral safety, and turnover in the house of representatives, 1952–1976. The American Political Science Review, 75, 119–131.

Congleton, R. D. (2006). The story of Katrina: New Orleans and the political economy of catastrophe. Public Choice, 127(1), 5–30.

Cover, A. D. (1976). One good term deserves another: The advantage of incumbency in congressional elections. Paper Presented to the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago.

Cox, G. W., & Katz, J. N. (1996). Why did the incumbency advantage in U.S. house elections grow?. American Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 478.

Dawson, P. A., & Zinser, J. E. (1976). Political finance and participation in congressional elections. American Academy of Political and Social Science Annals, 425, 59–73.

Erikson, R. S. (1971). The advantage of incumbency in congressional elections. Polity, 3(3), 395–405.

Erikson, R. S. (1972). Malapportionment, gerrymandering, and party fortunes in congressional elections. American Political Science Review, 66(04), 1234–1245.

Erikson, R. S., & Palfrey, T. R. (2000). Equilibria in Campaign spending games: Theory and data. American Political Science Review, 94(3), 595–609.

Evans, D. (2004). Greasing the wheels: Using pork-barrel politics to build majority coalitions in congress. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ferejohn, J. A. (1977). On the decline of competition in congressional elections. American Political Science Review, 71(01), 166–176

Feldman, P., & Jondrow, J. (1984). Congressional elections and local federal spending. American Journal of Political Science, 28, 147–163.

Ferejohn, J. A., & Krehbiel, K. (1987). The budget process and the size of the budget. American Journal of Political Science, 296–320.

Fiorina, M. P. (1977). The case of the vanishing marginals: The bureaucracy did it. American Political Science Review, 71(01), 177–181.

Frisch, S. A. (1998). The politics of pork: A study of congressional appropriations earmarks. New York: Garland Publishing.

Garand, J. C., & Gross, D. A. (1984). Changes in the vote margins for congressional candidates: A specification of historical trends. American Political Science Review, 78(01), 17–30.

Gelman, A., & King, G. (1990). Estimating incumbency advantage without bias. American Journal of Political Science, 34(4), 1142.

Glantz, S. A., Abramowitz, A. I., & Burkhart, M. B. (1976). Elections outcomes: Whose money matters? Journal of Politics, 38, 1033–1038.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. American Economic Review, 84(4), 833–850.

Inman, R. P. (1988). Federal assitance and local services in the United States: The evolution of a new federalist fiscal order. In Fiscal federalism: Quantitative studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (for NBER).

Inman, R. P., & Fitts, M. A. (1990). Political institutions and fiscal policy: Evidence from the US historical record. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 6(SPEC. ISSUE), 79–132.

Jacobson, G. C. (1976). Practical consequences of Campaign finance reform: An incumbent protection act. Public Policy, 24, 1–32.

Jacobson, G. C. (1978). The Effects of Campaign spending in congressional elections. The American Political Science Review, 72(2), 469–491.

Jacobson, G. C. (1987). The marginals never vanished: Incumbency and competition in elections to the U.S. house of representatives, 1952–82. American Journal of Political Science, 31(1), 126.

Jacobson, G. C. (1990). The electoral origins of divided government: Competition in U.S. house elections, 1964–1988. Boulder, CO: Westview.

King, G., & Gelman, A. (1991). Systemic consequences of incumbency advantage in U.S. house elections. American Journal of Political Science, 35(1), 110.

Keefer, P., & Khemani, S. (2009). When do legislators pass on pork? The role of political parties in determinating legislator effort. American Political Science Review, 103, 99–112.

Klingensmith, J. Z. (2016). Pork-barrel spending and state employment levels: Do targeted national expenditures increase state employment in the long run?. The Review of Regional Studies, 46(3), 257–279.

Krehbiel, K., & Wright, J. R. (1983). The incumbency effect in congressional elections: A test of two explanations. American Journal of Political Science, 27(1), 140.

Levitt, S. D., & Wolfram, C. D. (1997). Decomposing the sources of incumbency advantage in the U. S. house. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 22(1), 45.

Levitt, S. D., & Snyder, J. M. (1997). The impact of federal spending on house election outcomes. Journal of Political Economy, 105, 30–53.

Mayhew, D. R. (1974). Congress: The electoral connection. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Niou, E. M., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1985). Universalism in congress. American Journal of Political Science, 246–258.

Palda, K. S. (1973). Does advertising influence votes? An analysis of the 1966 and 1970 Quebec elections. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 6, 638–655.

Palda, K. S. (1975). The effect of expenditure on political success. Journal of Law and Economics, 18, 745–771.

Pastine, I., & Pastine, T. (2012). Incumbency advantage and political campaign spending limits. Journal of Public Economics, 96(1–2), 20–32.

Perdue, L. (1977). The million-dollar advantage of incumbency. Washington Monthly, 9, 50–54.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rogers, J. R. (2002). Free riding in state legislatures. Public Choice, 113(1–2), 59–76.

Samuels, D. J. (2002). Pork barreling is not credit claiming or advertising: Campaign finance and the sources of the personal vote in Brazil. The Journal of Politics, 64(3), 845–863.

Shepsle, K. A., Dickson, E. S., & Van Houweling, R. P. (2002). Bargaining in legislatures with overlapping generation of politicians. In Working paper.

Shepsle, K. A., & Weingast, B. R. (1981). Structure-induced equilibrium and legislative choice. Public Choice, 37, 503–519.

Sobel, R. S., Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2007). The political economy of FEMA: Did reorganization matter? Journal of Public Finance and Public Choice, 17, 49–65.

Stein, R. M., & Bickers, K. N. (1994). Congressional elections and the pork barrel. Journal of Politics, 56, 377–399.

Stein, R. M., & Bickers, K. N. (1995). Perpetuating the pork barrel: Policy subsystems and american democracy. Camridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Stratmann, T. (2013). The effects of earmarks on the likelihood of relection. European Journal of Political Economy, 32, 341–355.

Weingast, B. R. (1979). A rational choice perspective on congressional norms. American Journal of Political Science, 245–262.

Weingast, B. R., Shepsle, K. A., & Johnsen, C. (1981). The political economy of benefits and costs: A neoclassical approach to distributive politics. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 642–664.

Welch, W. P. (1974). The economics of campaign funds. Public Choice, 20, 83–97.

Welch, W. P. (1976). The effectiveness of expenditures in state legislative races. American Politics Quarterly, 4, 333–356.

Welch, W. P. (1977). Money and votes: A simultaneous equation model. In Paper presented to Public Choice Society, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

As an additional test of robustness, I conduct a three state least squares (3SLS) regression repeating the previous regressions. The results are given below (Table 7). The two simultaneous equations used are

-

1.

$$fundraising = \delta_{0} + \delta_{1} \cdot pork + \delta_{2} z_{k} + r_{k}$$

-

2.

$$Incumbent\;Election \;Percentage = \beta_{0} + \beta_{2} \cdot fundraising + \beta_{3} \cdot X_{i} + \varepsilon_{i} .$$

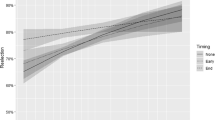

The top half of the table gives the results for the vote share regressions while the bottom half of the table gives the results for the fundraising regressions. The results for the set of regressions which use total incumbent fundraising are essentially identical under both the 2SLS and 3SLS frameworks. Therefore, I will not discuss them at any more length. The results for the set of regressions which use the share of fundraising do differ to some degree, but only within the fundraising regression. Pork-barrel spending, specifically during the election year, is shown to be significant and positively correlated with the incumbent’s share of fundraising and the incumbent’s share of fundraising is shown to be significant and positively correlated with the incumbent’s share of the votes in the general election.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klingensmith, J.Z. Using tax dollars for re-election: the impact of pork-barrel spending on electoral success. Const Polit Econ 30, 31–49 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-018-9269-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-018-9269-y