Abstract

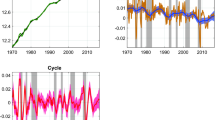

This study provides evidence on the interaction between business and credit cycles in Spain during the period 1970–2014. The paper works on three analyses: the cycle turning points are identified; the main features of credit and business cycles are documented; and in both cycles the causal relationship is assessed. We find differences in the features of the business and credit cycle phases, which lead to a scant degree of synchronization over time. The lack of synchronization might be a sign that the cyclic interaction could be non-contemporaneous. Our results reveal that there is causation. A significant lagged relationship between business and credit cycles is found; specifically, fluctuations of the business cycle lead fluctuations of the credit to non-financial corporations and a lag exists with respect to the fluctuations of the credit to households. We also examine episodes of credit boom and credit crunch. In the period 1970–2014, Spanish credit booms did not involve deeper business cycle contractions and credit crunches were not associated with deeper and longer business cycle contractions. These differences are related with the great importance of the real estate sector in Spain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Schularick and Taylor (2012) summarise the historical context of business and credit cycles.

Schularick and Taylor (2012) show that Spain reached a state of financial catch-up in the 1870–1939 period relative to the main developed countries and achieved subsequent rapid credit growth in the pre-Second World War period. In the post-war period, both ratios increased, as in the rest of the developed countries.

In 1985, debt securities accounted for almost 10 % of the Spanish financial assets, in 2005 they had reached 35 % and with the crisis they decreased to about 19 %.

As the authors acknowledge, their findings contrast with those of other studies on this subject. In this sense, the study provides an accurate review of the related literature.

The series data of the households include non-profit institutions serving households (NPISHs).

De la Fuente (2012) draws up a linked series of Spanish employment and GDP for the period 1955–2010.

The ‘classical business cycle’, on the basis of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), focuses on changes in the levels of economic activity. An alternative methodology to the ‘classical business cycle’ is the ‘growth cycle’, which can be approximated by analysing the ‘growth rates’ or the ‘deviation cycle’. Many authors recommend studying cycles by means of the ‘growth cycle’ and demonstrate its advantages; see for example Niemira and Klein (1994) or Diebold and Rudebusch (1999).

The turning points identified are robust to changes in the censoring rules. A robustness analysis can be found in the Appendix.

A review of the banking crisis in Spain during the period 1977–2012 is available in Ontiveiros and Valero (2013).

Peydró (2013) identifies several factors that explain the excessive credit boom and lending standards’ deterioration in the Spanish real estate market before this crisis.

The average business cycle contraction lasts about 11 quarters, which might suggest that Spanish contractions are very long. However, this result fits with other studies which provide a chronology of business cycle turning points for Spain. See, for instance, Bengoechea et al. (2002), Camacho et al. (2008), Álvarez and Cabrero (2010b) or Bergé and Jordà (2013).

There are other possibilities to define a credit boom. For instance, Dell’Ariccia et al. (2012) and Laeven and Valencia (2012) define credit boom years as those during which the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio relative to its trend is greater than 1.5 times its historical standard deviation and its annual growth rate exceeds 10 % or years during which the annual growth rate of the credit-to-GDP ratio exceeds 20 %.

In Xu (2012), we can find a review of the literature on financial frictions and their impact on the real economy.

The two-way relationship is one of the most important outcomes; however, we can find papers that provide different empirical evidence. For instance, Gordon and He (2008) argue that there is no relationship between the financial cycle and the business cycle. Arcand et al. (2012) find a threshold above which financial development has a negative effect on output growth. Samargandi et al. (2014) conclude that financial development and economic growth are not linearly related (inverted U-shape relationship). Furthermore, Hook and Singh (2014) provide an excellent summary of papers that defend such a non-monotonic relationship between finance and growth.

Doménech et al. (2014) describe the role played by the reasons that we highlight below in the evolution of bank financing to Spanish corporations before, during and at the end of the 2007 crisis.

Jiménez and Saurina (2006) find this behaviour in the granting of credit in Spain since the 1980s, when the Spanish financial liberalisation process began to strengthen. Banks have tended to expand credit without looking at the risk hedging.

References

Aikman D, Haldane AG, Nelson BD (2015) Curbing the Credit Cycle. Econ J 125(585):1072–1109

Alessi L and C Detken (2009) Real time early warning indicators for costly asset price boom/bust Cycles: A role for global liquidity. ECB Working Paper 1039

Alvárez LJ, Cabrero A (2010a) La evolución cíclica de la inversión residencial: algunos hechos estilizados. Boletín Económico, Banco de España, pp 56–63

Alvárez LJ, Cabrero A (2010b) Does housing really lead the Business cycle? Documentos de trabajo 1024, Banco de España

Anguren R (2012) Identificación y evolución de los ciclos de crédito en las economías avanzadas. Estabilidad Financiera, Banco de España 22:123–139

Arcand J L, Berkes E and Panizza, U (2012) Too much finance? IMF Working Paper 12/161

Arias F, Gaitán C, López J (2014) Las entidades financieras a lo largo del ciclo de negocio: ¿está el ciclo financiero sincronizado con el ciclo de negocios? Ensayos sobre Política Econ 32:28–40

Barbone R, Lima J and Marinho L (2015) Business and financial cycles: an estimation of cycles’ length focusing on macroprudencial policy. Working papers, Banco Central Do Brasil 385

BBVA Research (2014) Hechos estilizados del ciclo inmobiliario español. Situación España, cuarto trimester: 39–49

Becker B, Ivashina V (2014) Cyclicality of credit supply: firm level evidence. J Monet Econ 62:76–93

Bengoechea P, Guha D and K A Philip (2002): Determination of reference cycles according to the NBER approach: application to the Spanish economy during the period 1970–1999. Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI) working paper no. 2002/1a

Berge TJ, Jordà Ò (2013) A chronology of turning points in economic activity: Spain, 1850–2011. SERIEs 4(1):1–34

Bernanke B, Gertler M (1989) Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 79(1):14–31

Bernanke BS, Gertler M and Gilchrist S (1999) The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework in Taylor, JB, Woodford, M (Eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics vol. 1, chapter 21: 1341–1393

Borio CEV and Lowe P (2002) Assessing the risk of banking crises. BIS Quarterly Review December: 43–54

Borio CEV and Lowe P (2004) Securing sustainable price stability. Should credit come back from the wilderness? BIS Working Papers 157

Borio CEV, Zhu H (2012) Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: a missing link in the transmission mechanism? J Financ Stab 8(4):236–251

Borio CEV, Kennedy N and Prowse SD (1994) Exploring aggregate asset price fluctuations across countries: measurement, determinants and monetary policy implications. BIS Economic Papers 40

Brunnermeier MK, Sannikov Y (2014) A macroeconomic model with a financial sector. Am Econ Rev 104(2):379–421

Bry G, Boschan C (1971) Cyclical analysis of time series: selected procedures and computer programmes. National bureau of Economic Research, New York

Burns AF, Mitchell WC (1946) Measuring Business Cycles. NBER, Studies in Business Cycle. Columbia University Press, New York

Busch U (2012) Credit cycles and business cycles in Germany: A comovement analysis. Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): http://ssrn.com/abstract=2015976

Camacho M, Perez-Quiros and Saiz L (2008) Do European business cycles look like one? J Econ Dyn Control 32(7):2165–2190

Claessens S, Kose MA, Terrones ME (2009) What happens during recessions, crunches and busts? Econ Policy 24(60):653–700

Claessens S, Kose MA and Terrones ME (2011) Financial cycles: What? How? When? IMF Working Paper WP/11/76

Claessens S, Kose MA, Terrones ME (2012) How do business and financial cycles interact? J Int Econ 87(1):178–190

Comin D, Gertler M (2006) Medium-term business cycles. Am Econ Rev 96(3):523–552

Covas F, den Haan W (2011) The role of debt and equity finance over the business cycle. Am Econ Rev 101(2):877–899

De la Fuente A (2012) Series enlazadas de empleo y VAB para España, 1955–2010 (RegDat_Nac versión 3.1). Documentos de Trabajo número 12/25, BBVA Research

Dell’Ariccia G, Igan D, Laeven L and Tong H (2012) Policies for Macrofinancial Stability: How to Deal with Credit Booms. IMF Staff Discussion Note No. 12/06

Dembiermont C, Drehmann M, Muksakunratana S (2013) How much does the private sector really borrow? A new database for total credit to the private non-financial sector. Bank Int Settle (BIS) Quart Rev 2013:65–81

Detken C and Smets F (2004) Asset price booms and monetary policy. ECB Working Paper Series 364

Díaz A and Jerez B (2010) House prices, Sales, and Time on the market: a search-theoretic framework. Documento de trabajo Series Económicas 10–33. Universidad Carlos III

Diebold FX, Rudebusch GD (1999) Business cycles: durations, dynamics, and forecasting. Princeton University Press, Princenton

Doménech R, Fernández S, Ruesta M (2014) Tendencias recientes en la financiación bancaria a la empresa española. Info Comerc Española 879:11–27

Drehmann M, Borio C and Tsatsaronis K (2012) Characterising the financial cycle: don’t lose sight of the medium term! BIS Working Papers 380

English W, Tsatsaronis K, Zoli E (2005) Assessing the predictive power of measures of financial conditions for macroeconomic variables. Invest Relationship Betw Financ Real Econ, BIS Pap 22:228–252

European Central Bank (ECB) (2009) Loans to the non-financial private sector over the business cycle in the euro area. Monthly Bulletin October, ECB: 18–32

European Central Bank (ECB) (2013) Stylised facts of money and credit over the business cycle. Monthly Bulletin October, ECB: 18–25

Fiorentini G and Planas Ch (2003) User manual BUSY-Program. EC Fifth Framework Program, Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, Ispra, Italy

Gerdesmeier D, Reimers H-E, Roffia B (2010) Asset price misalignments and the Role of money and credit. Int Finance 13(3):377–407

Giannone D, Lenza M and Reichlin L (2012) Money, credit, monetary policy and the business cycle in the euro area. ECARES Working Paper 2012–008

Gómez-González JE, Ojeda-Joya JN, Tenjo-Galarza F and Zárate HM (2013) The interdependence between credit and real business cycle in Latin American economies. Borradores de Economía, 768, Banco de la República de Colombia

Goodhart C, Hofmann B (2008) House prices, money, credit, and the macroeconomy. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 24(1):180–205

Gorton G and Winton A (2003) Financial intermediation in George M Constantinides, Milton Harris and René M Stulz (Eds). Handbook of the Economics of Finance, Volume 1 Part A, Chapter 8: 431–552

Hammersland R and Bolstad C (2011) The financial accelerator and the real economy. Self-reinforcing feedback loops in a core macroeconomic model for Norway. EWP 2011/11, Eurostat, European Commission

Harding D, Pagan A (2002) Dissecting the cycle: a methodological investigation. J Monet Econ 49(2):365–381

Harding D, Pagan A (2006) Synchronization of cycles. J Econ 132(1):59–79

Hatzius J, P Hooper, F Mishkin, K Schoenholtz and M Watson (2010) Financial conditions indexes: a fresh look after the financial crisis. NBER Working Papers 16150

Helbling T, Huidrom R, Kose MA, Otrok C (2011) Do credit shocks matter? A global perspective. Eur Econ Rev 55(3):340–353

Hook S, Singh N (2014) Does too much finance harm economic growth? J Bank Financ 41(C):36–44

Jiménez G and J Saurina (2006) Credit cycles, credit risk, and prudential regulation. Int J Central Bank 65–98

Jiménez G, Ongena S, Peydró J-L, Saurina J (2012) Credit supply and monetary policy: identifying the bank balance-sheet channel with loan applications. Am Econ Rev 102(5):2301–2326

Jordà O, Schularick M, Taylor AM (2011) Financial crises, credit booms, and external imbalances: 140 years of lessons. IMF Econ Rev 59(2):340–378

Jordà O, Schularick M, Taylor AM (2014) When credit bites back. J Money Credit Bank 45(s2):3–28

Kalemli-Ozcan S, Papaioannou E, Peydró J-L (2013) Financial regulation, financial globalization, and the synchronization of economic activity. J Financ 68(3):1179–1228

Karfakis C (2013) Credit and business cycles in Greece: is there any relationship? Econ Model 32:23–29

Kiyotaki N, Moore J (1997) Credit cycles. J Polit Econ 105:211–248

Laeven L and F Valencia (2012) Systemic banking crises database: an update. IMF Working Paper 12/163

Leamer EE (2007) Housing is the business cycle. NBER Working Papers 13428

Levine R (2005) Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence in Philippe Aghion & Steven Durlauf (Eds.). Handbook of Economic Growth, edition 1, volume 1, chapter 12: 865–934

Lucas Jr, RE (1977) Understanding business cycles, in Karl Brunner, K. and Meltzer A. (Eds.). Stabilization of the domestic and international economy, Amsterdarm: North Holland

Minsky HP (1982) The financial-instability hypothesis: capitalist processes and the behaviour of the economy in Kindleberger, CP, Laffargue, J (Eds.). Financial crises. University Press, Cambridge (Chapter 2): 13–47

Newey WK, West KD (1987) A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity, & autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55(3):703–708

Ng T (2011) The predictive content of financial cycle measures for output fluctuations. BIS Quart Rev 53–65

Niemira M, Klein PA (1994) Forecasting Financial and Economic Cycles. Wiley, New York

Ontiveiros E, Valero J (2013) Las crisis bancarias en España 1977–2012. Rev Historia Econ Empresa 7:277–317

Peydró J-L (2013) Credit cycles and systemic risk. Els Opuscles del Crei. Centre de Recerca en Economia Internacional, 35

Reinhart CM, Rogoff KS (2011) From financial crash to debt crisis. Am Econ Rev 101(5):1676–1706

Samargandi JF, Fidrmuc J and Ghosh S (2014) Is the relationship between financial development and economic growth monotonic? Evidence from a sample of middle income countries. CESifo Working Paper, 4743

Schularick M, Taylor AM (2012) Credit booms gone bust: monetary policy, leverage cycles, and financial crises, 1870–2008. Am Econ Rev 102(2):1029–1061

Sichel D (1993) Business cycle asymmetry: a deeper look. Econ Inq 31(2):224–236

Xu TT (2012) The role of credit in international business cycle. Workink Paper 2012–36, Bank of Canada

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix. Turning points robustness check

Appendix. Turning points robustness check

One might wonder about the extent to which the cycles identified are sensitive to the methodology used and, in particular, to the censoring rules established in relation to the duration of the phases and cycles. We carry out a robustness check to examine this sensitivity of the results. We calculate the turning points, softening the constraints to the fullest extent allowed by the BUSY programme. In particular, we calculate the turning points according to the censoring rules reported in Table 12.

The turning points calculated under the constraints of each row of Table 12 are identical to those reported in Table 1. The censoring rules imposed by the methodology do not affect the results; thus, we conclude that the nature of the results is robust.

About this article

Cite this article

Sala-Rios, M., Torres-Solé, T. & Farré-Perdiguer, M. Credit and business cycles’ relationship: evidence from Spain. Port Econ J 15, 149–171 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-016-0124-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-016-0124-7