Abstract

Background

Episode-based payment (EBP) is gaining traction among payers as an alternative to fee-for-service reimbursement. However, there is concern that EBP could influence the number of episodes.

Objective

To examine how procedure volume changed after the introduction of EBP in 2013 and 2014 under the Arkansas Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative.

Design

Using 2011–2016 commercial claims data, we estimate a difference-in-differences model to assess the impact of EBP on the probability of a beneficiary having an episode for four procedures that were reimbursed under EBP in Arkansas: total joint replacement, cholecystectomy, colonoscopy, and tonsillectomy.

Participants

Commercially insured beneficiaries in Arkansas serve as our treatment group, while commercially insured beneficiaries in neighboring states serve as our comparison group.

Interventions

Statewide implementation of EBP for various clinical conditions by two of Arkansas’ largest commercial insurers.

Main Measures

For a given procedure type, the primary outcomes are the annual rate of procedures (number of procedures per 1000 beneficiaries) and the probability of a beneficiary undergoing that procedure in a given quarter.

Key Results

The relationship between EBP and procedure volume varies across procedures. After EBP was implemented, the probability of undergoing colonoscopy increased by 17.2% (point estimate, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.18 to 4.08; p < 0.001; Arkansas pre-period mean, 15.29). The probability of undergoing total joint replacement increased by 9.9% (point estimate, 0.091; 95% CI, − 0.011 to 0.19; p = 0.08; Arkansas pre-period mean, 0.91), though this effect is not significant. There is no discernable impact on cholecystectomy or tonsillectomy volume.

Conclusions

We do not find clear evidence of deleterious volume expansion. However, because the impact of EBP on procedure volume may vary by procedure, payers planning to implement EBP models should be aware of this possibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Facing pressure to better control health care spending and address inefficiencies in the delivery system, public and private payers have been experimenting with alternative payment models. One model that is gaining traction is episode-based (or bundled) payment (EBP). Under EBP, there is a single spending target for all services delivered during an episode of care, and these services span time, sites of care, and specific providers. For example, an episode might include a surgical procedure and all related services (e.g., pre-operative office visits, post-acute care, readmissions) that the patient receives during a defined time period (e.g., 30 days) before and after the procedure. By aggregating reimbursement across these services and settings, EBP (in theory) incentivizes efforts to improve the efficiency and coordination of care.

The emerging literature finds mixed results regarding the impact of EBP on spending, with the effect varying across the specific procedures and conditions that are bundled. For example, there is evidence1, 2 of savings under Medicare’s voluntary Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative for lower extremity joint replacement episodes, but not for several other conditions.3, 4 While initial results5 from Medicare’s mandatory Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model show no significant change in total spending per episode, more recent work6 finds a decrease in institutional spending per episode. In the commercial sector, an evaluation of EBP for perinatal care in Arkansas estimates that total episode spending decreased during the first year of full implementation.7

Beyond its impact on spending, analysts have raised concerns about the impact of EBP on the number of episodes.1, 4,5,6, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Providers can adjust episode volume because they often exercise discretion over whether to perform a procedure and over patient referrals. These decisions can also be influenced by financial incentives. Under EBP, providers can earn bonus payments if they increase the number of patients treated with spending below the payer-specified target, which can be achieved by either reducing per-episode spending (e.g., through efficiencies during care delivery) or selectively treating low-severity patients (who have lower expected costs). Conversely, because bonuses are based on average spending, providers can also benefit if they treat fewer complex patients (who have higher expected costs). The net effect on procedure volume is ambiguous. However, if providers encourage patients to undergo procedures that are not clinically necessary, there could be over-treatment that then offsets any per-episode savings. At the same time, there could be under-treatment if providers avoid treating sicker patients.

There is limited research on the volume effects of EBP, and the existing work focuses on lower extremity joint replacement.5, 6, 14 However, the evidence on how EBP impacts spending varies across episodes, suggesting that the impact on volume may also vary by condition. Thus, it is crucial to expand the set of episodes analyzed. Furthermore, most research to date evaluates Medicare EBP models. It is therefore important to understand how providers might respond to EBP in other patient populations.

In this study, we examine the impact of EBP on procedure volume for different types of episodes. Our empirical setting is Arkansas, where the state’s Medicaid program and two of its largest commercial insurers began adopting EBP for a variety of clinical conditions in 2012. Arkansas’ EBP model uniquely features statewide implementation, multi-payer involvement, mandatory provider participation, and novel episodes.15

EPISODE-BASED PAYMENT IN ARKANSAS

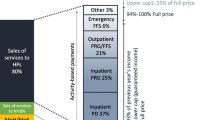

Launched in 2012, the Arkansas Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative is an attempt to move the state’s public and private payment systems toward value-based purchasing. One of its core components is an EBP model, in which Arkansas Medicaid, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield (AR BCBS), and QualChoice (QC) jointly participate. Prior to EBP, these insurers reimbursed providers on a fee-for-service basis.

Provider participation in EBP is mandatory. For each episode, a principal accountable provider (PAP), who is generally the physician that performs the procedure, is identified through claims data and held responsible for total episode spending. Providers are paid fee-for-service during the course of the year. Then, at the end of a performance period (usually 1 year), the payer calculates a PAP’s risk-adjusted16 average spending across all valid episodes and compares it to pre-determined thresholds, which are based on the payer’s historical spending in Arkansas. These thresholds establish “commendable,” “acceptable,” and “unacceptable” spending levels. PAPs with “commendable” spending that also meet specified quality metrics receive 50% of the savings, up to a gainsharing limit. PAPs with “unacceptable” spending must pay back 50% of excess costs above the “acceptable” threshold. Further details are available in the Online Appendix.

Our analysis focuses on four episode types: total joint replacement, cholecystectomy, colonoscopy, and tonsillectomy. We chose these particular episodes because they are primarily elective in nature, and thus there is greater opportunity for volume expansion.8, 17 Also, compared with other episodes covered under Arkansas’ EBP reform, they occur more frequently and therefore provide larger (though still limited) sample sizes for the analysis.18 There are slight differences across episodes in terms of when commercial EBP was implemented and whether both AR BCBS (79% of the large group market) and QC (6% of the large group market) participate in the model.19

METHODS

Data

Our primary data source is the 2011–2016 Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database—a convenience sample of enrollees in commercial health insurance plans offered by large employers across the USA. We restrict our sample to beneficiaries who are continuously enrolled for the entire year20 and in health maintenance organization, point-of-service, preferred provider organization, consumer-driven health, and high-deductible health plans, because these plan types have adequate sample size to allow us to control for plan type.21

Identifying Episode Triggers

An episode is triggered by a specific procedure code, and we exclude repeated episodes for the same patient (see Online Appendix). Each payer also publishes criteria regarding which episodes would be excluded from EBP (e.g., episodes for patients with certain high-cost comorbidities). The potential for providers to “game” the exclusions (e.g., by coding intensive patients in a manner such that their episodes are excluded from gainsharing calculations) raises concerns about examining only “valid” episodes. To eliminate this concern, we do not apply the exclusion criteria.

Analyses

We analyze each episode type separately because responses may vary by clinical area, participating payers differ, and the episode types had slightly different start dates (which creates different pre- and post-EBP periods across the conditions). For total joint replacement, the pre-period is 2011–2012 and post-period is 2013–2016. For cholecystectomy, colonoscopy, and tonsillectomy, the pre-period is 2011–2013 and post-period is 2014–2016.

Our control group consists of commercially insured beneficiaries drawn from states that geographically border Arkansas or are also located in the South Central Census Divisions.22 We omit Tennessee as a potential control state, because it launched its own EBP reforms in 2013. We also exclude Kentucky and Oklahoma from the analysis, because of sharp changes in their MarketScan samples over time. Therefore, our baseline set of control states includes Missouri, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.23 For each episode type, we test for differential pre-EBP trends in the outcome variables between Arkansas and the control states (see Online Appendix). We only include states in the final control group if their pre-trends are not significantly different from Arkansas’ pre-trend. For all episodes except colonoscopy, all five baseline states pass the pre-trends test.

For each episode type, we plot the annual rate of episode-triggering procedures (number of procedures that occurred in a given year divided by the number of continuously enrolled MarketScan beneficiaries) for Arkansas and for the pooled control states. We utilize a difference-in-differences empirical strategy to formally measure the impact of EBP on the probability of a beneficiary having an episode. We describe our econometric model in the Online Appendix.

We perform a series of robustness checks. First, we determine if our results are sensitive to the choice of control states by repeating the analysis dropping each control state in sequence and pooling the remaining four states. Second, as placebo tests, we repeat the analysis on five common procedures that were not subject to EBP during the study period: lumbar spinal fusion, inguinal hernia repair, appendectomy, upper endoscopy, and cataract surgery. We test the hypothesis that EBP had no significant effect on the volume of these procedures (see Online Appendix). Third, we try adjusting our p values for multiple comparisons.24, 25

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 15.1, StataCorp). We utilize two-tailed hypothesis tests with a statistical significance threshold of α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Study Population

Both before and after EBP implementation, beneficiaries in Arkansas and the control states are close in mean age, though there are slightly more females in the control states (Table 1). There are also some differences in plan type. Nonetheless, changes over time in beneficiary characteristics are similar between Arkansas and the control states.

Total Joint Replacement

For our analysis of the total joint replacement episode, we restrict the sample to beneficiaries ages 40–64 (Fig. 1). The trends (and levels) for Arkansas and the control group are similar during the pre-EBP period (2011–2012). However, the trends diverge after full EBP implementation is achieved in 2014. Our difference-in-differences estimate of the EBP effect is a 9.9% increase (p = 0.08) in the probability of undergoing total joint replacement in a given quarter, relative to the Arkansas pre-period mean per 1000 beneficiaries of 0.91 (Table 2). While this estimated effect is large in magnitude, it is not statistically significant. When we sequentially drop control states, our estimate of the EBP effect ranges from a 7.4% increase (p = 0.19) when dropping Alabama to a 13.6% increase (p = 0.049) when dropping Texas (Table A-1).

Rate of total joint replacement episode–triggering procedures. Blue diamonds indicate annual rates for Arkansas. Green squares indicate annual rates for all controls. The vertical orange line indicates partial commercial EBP implementation (AR BCBS only) in 2013. The vertical maroon line indicates full commercial EBP implementation (AR BCBS and QC) in 2014. All controls refers to Missouri, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Source: Authors’ analysis of Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters data for 2011–2016.

We repeat the analysis for lumbar spinal fusion, a comparable orthopedic surgical procedure that was not reimbursed under EBP (Figure A-1). Our difference-in-differences estimate of the post-EBP effect suggests a 9.0% increase (p = 0.39) in the probability of undergoing lumbar spinal fusion during a given quarter (Table A-2). Although this estimate is positive and has sizeable magnitude, it is not statistically significant; it also reflects an unexplained drop in 2012 (before EBP was introduced), and the increase does not persist.

Cholecystectomy

For our analysis of the cholecystectomy episode, we restrict the sample to beneficiaries ages 18–64 (Fig. 2). Our difference-in-differences estimate of the EBP effect is a 3.6% decrease (p = 0.09) in the probability of undergoing cholecystectomy during a given quarter, relative to the Arkansas pre-period mean per 1000 beneficiaries of 1.7 (Table 2). We repeat the analysis using alternative control groups, and the estimated effect ranges from a 3.1% decrease (p = 0.14) when dropping Alabama to a 4.2% decrease (p = 0.06) when dropping Missouri (Table A-3).

Rate of cholecystectomy episode–triggering procedures. Blue diamonds indicate annual rates for Arkansas. Green squares indicate annual rates for all controls. The vertical maroon line indicates commercial EBP implementation (AR BCBS and QC) in 2014. All controls refers to Missouri, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Source: Authors’ analysis of Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters data for 2011–2016.

We repeat the analysis for inguinal hernia repair (Figure A-2) and appendectomy (Figure A-3), two surgical procedures that were not subject to EBP during the study period. Our difference-in-differences estimates of the post-EBP effect for inguinal hernia repair and appendectomy suggest a 3.1% (p = 0.69) and 4.9% decrease (p = 0.57) in probability, respectively (Table A-4, Table A-5).

Colonoscopy

For our analysis of the colonoscopy episode, we restrict the sample to beneficiaries ages 40–64 (Fig. 3).26 We find that only Alabama and Louisiana have pre-trends that are statistically similar to Arkansas, so the control group includes these two states only. Our difference-in-differences results indicate that after EBP was implemented, the probability of undergoing colonoscopy during a given quarter increased by 17.2% (p < 0.001), relative to the Arkansas pre-period mean per 1000 beneficiaries of 15 (Table 2). If we include all five baseline states in the control group, we obtain similar results: an estimated increase in probability of 15.6% (p < 0.001) (Table A-6).

Rate of colonoscopy episode–triggering procedures. Blue diamonds indicate annual rates for Arkansas. Green squares indicate annual rates for all controls. Red triangles indicate annual rates for Alabama and Louisiana. The vertical maroon line indicates commercial EBP implementation (AR BCBS) in 2014. All controls refers to Missouri, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. While we show the trend for all control states pooled, only Alabama and Louisiana pass the pre-trends test and thereby form the control group for our primary specification. Source: Authors’ analysis of Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters data for 2011–2016.

As a placebo test, we examine how volume changed for upper endoscopy, a related procedure that was not reimbursed under EBP (Figure A-4). We apply the same criteria as in our analysis of colonoscopy, so the control group contains Alabama and Louisiana only. During the post-EBP period, there is no evidence of a sustained increase in the rate of upper endoscopy in Arkansas. Our difference-in-differences results suggest a statistically non-significant 4.8% increase (p = 0.31) in the probability of undergoing upper endoscopy. Even when we include the full set of control states, the estimated effect remains statistically non-significant (Table A-7).

Tonsillectomy

For our analysis of the tonsillectomy episode, we restrict the sample to beneficiaries ages 3–21 (Fig. 4). Our difference-in-differences estimate of the EBP effect is a 2.9% decrease (p = 0.57) in the probability of undergoing tonsillectomy during a given quarter, relative to the Arkansas pre-period mean per 1000 beneficiaries of 1.9 (Table 2). Using alternative control groups, we find that the estimated effect ranges from a 0.7% decrease (p = 0.91) when dropping Texas to a 4.4% decrease (p = 0.38) when dropping Missouri (Table A-8).

Rate of tonsillectomy episode–triggering procedures. Blue diamonds indicate annual rates for Arkansas. Green squares indicate annual rates for all controls. The vertical maroon line indicates commercial EBP implementation (AR BCBS) in 2014. All controls refers to Missouri, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Source: Authors’ analysis of Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters data for 2011–2016.

In a placebo test, we analyze volume changes for cataract surgery, a common procedure that was not reimbursed under EBP (Figure A-5). Our difference-in-differences estimate of the post-EBP effect is a 1.2% decrease (p = 0.92) in the probability of undergoing cataract surgery during a given quarter (Table A-9).

DISCUSSION

Similar to the literature on spending per episode, we find that the relationship between EBP and procedure volume varies by procedure. The evidence for colonoscopy suggests a large, significant increase in volume. The effect on total joint replacement volume is also large in magnitude, but it is not statistically significant, and there is a sizeable increase for our related placebo procedure (lumbar spinal fusion). Therefore, we do not conclude that EBP had an impact on total joint replacement volume. There is no discernable impact on cholecystectomy or tonsillectomy volume. Thus, for certain procedures, the potential for volume expansion is meaningful. For other procedures, however, the impact on volume seems minimal.

Various clinical, organizational, and financial factors could be at play that facilitate volume expansion for certain procedures over others. For example, there is variation across procedures in providers’ ability to generate efficiencies, which impacts potential profit. Furthermore, there is variation across procedures in how much clinical flexibility providers have in recommending the procedure to patients, and in how many eligible patients are at the margin of receiving care. Among our selected episodes, the clinical indications for tonsillectomy and cholecystectomy are narrower. There is also limited room to increase efficiency during tonsillectomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedures. These factors may contribute to our finding of no volume changes following EBP implementation. In contrast, there is robust evidence demonstrating that colorectal cancer screening, which is recommended for adults ages 50 to 75, is substantially underutilized among the US population.27 This suggests that there is great potential for appropriate expansion. Accordingly, we find a large, significant increase in colonoscopy volume following EBP implementation.

Ultimately, the perceived consequences of volume expansion will differ depending on the nature of the procedure. While it would be an unfavorable result if volume increases for procedures that are not clinically appropriate, it would be favorable if volume increases for procedures that are clinically indicated. The increase in colonoscopy volume that we observe can potentially be viewed as a desirable shift of resources and may be beneficial to the population, assuming it occurs among clinically indicated patients. Although our data limits our ability to determine whether this increase is clinically indicated, roughly 71% of colonoscopies in our post-EBP Arkansas sample were performed on patients ages 50 and older, versus 67% prior to EBP.

Our study has several limitations. First, we cannot measure underlying need for the procedures at the population level or among those who received treatment. However, this would only bias our results if population-level need, controlling for age and gender, changed differentially across states, which we believe is unlikely. Also, because the only procedure for which we find clear evidence of volume expansion is colonoscopy (which is commonly recommended to older adults), we do not believe that there were significant increases in unindicated care.28 Second, we are unable to observe provider IDs or characteristics in MarketScan. While this limits our ability to identify differential effects across providers or provider types, unobserved provider characteristics would only bias our results if there were differential changes across states. We performed extensive testing to ensure that our control group provides a valid counterfactual, which mitigates this concern. Third, for each episode type, Arkansas Medicaid implemented EBP a few months before commercial payers did.29 To the extent that spillovers exist, our findings would underestimate volume changes because the effect would have begun before our analysis assumes. Additionally, some smaller commercial insurers in Arkansas do not participate in EBP. We are unable to identify insurers in MarketScan, so we may be capturing procedures for patients who are covered by non-participating insurers, which could dilute our results. However, non-participating insurers only comprise about 15% of the large group market,19 so the effects due to non-participating insurers are likely small and would bias us away from finding an effect. An additional limitation is that during the post-intervention period, providers in the control states could have been participating in Medicare EBP demonstrations for joint replacement (the only episode type that overlaps with our analysis). However, only a few providers participated in these demonstrations, and any changes to practice style would only impact the treatment of under-65, commercially insured beneficiaries through spillover effects. Lastly, Arkansas’ payment reforms also include a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) program, which was launched in 2014. To the extent that the PCMH program affects procedure volume, our estimates may be biased. In our placebo tests, we find that the volume of five non-EBP procedures did not change significantly between 2011–2013 and 2014–2016. Still, potential confounding could be of concern for colonoscopy, if the PCMH program (which promotes preventive care) differentially affects volume for colonoscopy versus upper endoscopy (our related placebo procedure).

Despite these limitations, our study provides the first evidence that, in a commercial population, the impact of EBP on procedure volume varies across procedures. Overall, our findings do not indicate significant volume expansion beyond that for colonoscopy, which is generally underutilized. Nevertheless, payers must be vigilant of the potential for volume expansion. Continued refinements to episode payment schemes and constant monitoring will be important for organizations hoping to transition to alternative payment models.

References

Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association Between Hospital Participation in a Medicare Bundled Payment Initiative and Payments and Quality Outcomes for Lower Extremity Joint Replacement Episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267–1278.

Navathe AS, Troxel AB, Liao JM, et al. Cost of Joint Replacement Using Bundled Payment Models. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):214–222.

Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Evaluation of Medicare’s Bundled Payments Initiative for Medical Conditions. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):260–269.

Dummit LA, Marrufo G, Marshall J, et al; The Lewin Group. CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative Models 2-4: Year 3 Evaluation & Monitoring Annual Report. 2017. Available at: https://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/bpci-models2-4yr3evalrpt.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2019.

Finkelstein A, Ji Y, Mahoney N, Skinner J. Mandatory Medicare Bundled Payment Program for Lower Extremity Joint Replacement and Discharge to Institutional Postacute Care: Interim Analysis of the First Year of a 5-Year Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(9):892–900.

Barnett ML, Wilcock A, McWilliams JM, et al. Two-Year Evaluation of Mandatory Bundled Payments for Joint Replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(3):252–262.

Carroll C, Chernew ME, Fendrick AM, Thompson J, Rose S. Effects of Episode-Based Payment on Health Care Spending and Utilization: Evidence from Perinatal Care in Arkansas. J Health Econ. 2018;61(2018):47–62.

Fisher ES. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Program for Joint Replacement: Promise and Peril? JAMA. 2016;316(12):1262–1264.

Weeks WB, Rauh SS, Wadsworth EB, Weinstein JN. The Unintended Consequences of Bundled Payments. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):62–64.

Cutler DM, Ghosh K. The Potential for Cost Savings through Bundled Episode Payments. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1075–1077.

Mechanic RE. Opportunities and Challenges for Episode-Based Payment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(9):777–779.

Ubel P. If We Cut Surgical Pay, Will Surgeons Cut Into More People? Forbes. 2017. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/peterubel/2017/09/18/if-we-cut-surgical-pay-will-surgeons-cut-into-more-people/#1b0602172c7f. Accessed 28 June 2019.

Baicker K, Chernew ME. Alternative Alternative Payment Models. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):222–223.

Navathe AS, Liao JM, Dykstra SE, et al. Association of Hospital Participation in a Medicare Bundled Payment Program with Volume and Case Mix of Lower Extremity Joint Replacement Episodes. JAMA. 2018;320(9):901–910.

Currently, the Arkansas EBP initiative features 20 clinical episodes, which have either been implemented, will be implemented, or are under development. Compared to the Medicare BPCI and BPCI Advanced models, the Arkansas model features a smaller number of episodes. However, the Arkansas initiative is novel in that it covers a broad scope of conditions and tests bundled payment for several conditions that are not included in the Medicare models. For example, the Arkansas model features various outpatient episodes, and it uniquely includes episodes for women’s health (e.g., perinatal care, hysterectomy), behavioral health (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder), and children’s health (e.g., neonatal care, pediatric pneumonia). A list of episodes is provided on page 43 of the AHCPII statewide tracking report, which is available at: https://achi.net/library/ahcpii-tracking-report/. Accessed 28 June 2019.

The use of risk adjustment is common to all episode types, but the actual algorithm and which specific risk factors are included may vary slightly across payers and across episode types. In general, the risk adjustment algorithm considers diagnoses, comorbidities, procedures, and demographic characteristics drawn from a patient’s historical claims data.

To the extent that the analyzed episodes are sometimes performed on an emergent basis, it could dampen the impact of EBP on provider behavior. Nonetheless, we believe that emergent cases constitute a small minority of the procedures analyzed.

The perinatal and asthma episodes were also implemented by commercial payers and have adequate sample size. However, we chose not to study the perinatal episode because we do not expect to find a volume expansion effect, as providers cannot plausibly induce additional births. We chose not to study the asthma episode due to two reasons. First, the asthma episode is not procedure-based, and our focus is on how procedure volume responds to EBP. Second, identifying asthma episode triggers in the claims data requires accurate and detailed coding of diagnoses; however, diagnoses are not coded consistently in the MarketScan data.

Market Share and Enrollment of Largest Three Insurers - Large Group Market. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/market-share-and-enrollment-of-largest-three-insurers-large-group-market/. Accessed June 28, 2019.

To construct our analytical dataset, we take repeated cross sections of continuously enrolled beneficiaries (one cross section for each year of 2011–2016). It is possible for a given beneficiary to appear in multiple cross sections over time, though this is not necessarily the case. Certain procedures that we analyze, like cholecystectomy and tonsillectomy, can only be performed on a patient once over time. Due to concern over serial correlation in the outcomes after a beneficiary undergoes these procedures, we drop that beneficiary from all cross sections following the date of the procedure.

We exclude the following plan types due to inadequate sample size: basic/major medical, comprehensive, exclusive provider organization, and point-of-service with capitation.

States that geographically border Arkansas are Missouri, Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma. The West South Central Census Division consists of Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana. The East South Central Census Division consists of Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama.

Our baseline control group differs slightly from that used in Carroll et al. (2018). We additionally include Missouri because it geographically borders Arkansas. We also include Texas. Carroll et al. include Kentucky and Oklahoma in their control group, whereas we exclude both states in our baseline specification. In a sensitivity analysis, we include Kentucky and Oklahoma in the control group, and we obtain similar results.

Westfall PH, Young SS. Resampling-Based Multiple Testing: Examples and Methods for p-Value Adjustment. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1993.

Jones D, Molitor D, Reif J. What Do Workplace Wellness Programs Do? Evidence from the Illinois Workplace Wellness Study. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 24229. Published January 2018. Revised June 2018. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w24229. Accessed 28 June 2019.

We consider diagnostic and screening colonoscopies together. We include ages 40 to 49 in case EBP induces volume expansion among patients under age 50, which is the US Preventive Services Task Force’s recommended threshold for colorectal cancer screening.

Maratt JK, Saini SD. Colorectal Cancer Screening in the 21st Century: Where Do We Go From Here? Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(7):e447-e449.

To increase colonoscopy volume, physicians may be modifying their labor supply, readjusting effort, or changing the mix of services that they provide (e.g., displacing certain procedures with colonoscopies). While these behavioral responses are important to understand, studying them is beyond the scope of our work.

Arkansas Medicaid implemented EBP for total joint replacement in October 2012 and for cholecystectomy, colonoscopy, and tonsillectomy in July 2013.

Funding

Research reported in this study was financially supported by a grant from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Chernew reports having equity in Archway Health, V-BID Health, Virta Health, and Paladin Healthcare Capital. He reports having consulted for the American Hospital Association, Anthem Health Insurance, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Madalena Consulting, Merck & Company, Milliman, Navigant, Pfizer, PhRMA, Precision Health Economics, State of North Carolina, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, University of Michigan, White & Case, Amgen, J&J, Sanofi, University of Maine, McKinsey & Company, and John Freedman Healthcare. He has received research funding from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, NIH/NIA, NBER/AHRQ, CMS via Abt Associates, MITRE/CMS, Altarum/RWJK, Peterson Center on Health Care, and The Commonwealth Fund. Dr. Fendrick reports having consulted for AbbVie, Amgen, Centivo, Community Oncology Association, Department of Defense, EmblemHealth, Exact Sciences, Freedman Health, Health at Scale Technologies, Health Management Associates, Lilly, MedZed, Penguin Pay, Risalto, Sempre Health, State of Minnesota, Wellth, and Zansors. He has received research funding from AHRQ, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gary and Mary West Health Policy Center, Laura and John Arnold Foundation, National Pharmaceutical Council, PCORI, PhRMA, RWJ Foundation, and State of Michigan/CMS. All other authors report no relationships or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 2.81 MB).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J.L., Chernew, M.E., Fendrick, A.M. et al. Impact of an Episode-Based Payment Initiative by Commercial Payers in Arkansas on Procedure Volume: an Observational Study. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 578–585 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05318-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05318-7