Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The practice of histopathological assessment of the uterus following hysterectomy for benign indications including pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery is common and often routine. While pathology is not anticipated, the finding of pathology requiring further action is always a concern, in particular CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) or cervical/uterine malignancy. We aimed to perform a systematic review to understand the prevalence of actionable uterine and cervical pathology in hysterectomy specimens performed for POP.

Methods

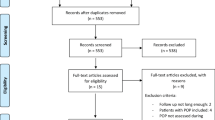

A literature search was performed in January 2020 of MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL using the Healthcare Databases Advanced Search platform. Included studies reported CIN and/or uterine/cervical malignancy in histological assessment of hysterectomy specimens performed purely for POP. Meta-analysis of prevalence was performed using the MetaXL (www.epigear.com) add-in for Microsoft Excel.

Results

Six hundred seventy-seven records were identified, out of which 34 studies were eligible. Overall prevalence (95% confidence interval [CI]) of endometrial cancer in 33 studies was 0.004 (0.003–0.006), I2 = 41%, number needed to treat (NNT) 1:250. Total actionable uterine pathology was 0.005 (0.003–0.006) in 33 studies, I2 = 35%, NNT = 1:200. Overall prevalence of cervical cancer in 19 papers was 0.001 (0.000–0.002), I2 = 18%, NNT = 1:1000. In 16 studies the overall prevalence of CIN was 0.013 (0.001–0.033), I2 = 95%, NNT = 1:77. Prevalence of total actionable pathology was 0.013 (0.006–0.0023), I2 = 86%, NNT = 1:77.

Conclusion

The risk of actionable pathology is low, but not negligible. The variation between populations is wide. The prevalence of finding such pathology supports the routine practice of sending all hysterectomy specimens performed for POP for histological assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Awale R, Isaacs R, Singh S, Manrelle K. Uterine prolapse: should hysterectomy specimens be subjected for histopathological examination. J Midlife Health. 2017;8(4):179–82. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmh.JMH_80_17.

Gene M, Gene B, Sabin N, Celik E, Turan GA, Gur EB, et al. Endometrial pathology in postmenopausal women with no bleeding. Climacteric. 2015;18:241–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2014.944152.

Grigoriadis T, Valla A, Zacharakis D, et al. Vaginal hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse: what is the incidence of concurrent gynecological malignancy? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2014;26:421–5 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2516-5.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Tandon A, Murray CJL, Lauer JA, Evans DB. Measuring overall health system performance for 191 countries. GPE Discussion Paper Series: No. 30 EIP/GPE/EQC World Health Organization.

Doi, S. A, J. J. Barendregt, S. Khan, L. Thalib and G. M. Williams (2015). Advances in the meta-analysis of heterogeneous clinical trials I: the inverse variance heterogeneity model. Contemp Clin Trials 45: 130-138. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.009.

Doi SA, Barendregt JJ, Khan S, Thalib L, Williams GM. Advances in the meta-analysis of heterogeneous clinical trials II: the quality effects model. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:123–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.010.

Doi SA, Thalib L. A quality-effects model for meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2008;19(1):94–100. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c24e7.

Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman R, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2013;67:974–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-203104.

Ackenbom MF, Giugale LE, Wang Y, Shepherd JP. Incidence of occult uterine pathology in women undergoing hysterectomy with pelvic organ prolapse repair. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22:332–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000283.

Andrews T, Monaghan H. Is microscopic examination of hysterectomy specimens removed for clinically benign disease necessary? J Clin Pathol. 2007;61:235–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2007.049601.

Andy UU, Harvie HS, Nosti PA, Gutman RE, Kane S, White DE, et al. Incidence of unanticipated uterine pathology at the time of minimally invasive abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a fellows’ pelvic research network study. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2012;18(5).

Aydin S, Bakar RZ, Mammadzade A, Dansuk R. The incidence of concomitant precancerous lesions in cases who underwent hysterectomy for prolapse. J Clin Anal Med. 2016;7:676–80. https://doi.org/10.4328/JCAM.4385.

Bonnar J, Kraszewski A, Davis WB. Incidental pathology at vaginal hysterectomy for genital prolapse. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 1970;77:1137–9 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1970.tb03479.x.

Channer JL, Paterson MEL, Smith JHF. Unexpected pathological findings in uterine prolapse: a 12-month audit. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:697–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13860.x.

Cheng MC, Ma WS. Risk of unexpected malignancy in Chinese women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:S234–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3752-x.

Dayal S, Nagrath A. Audit on preinvasive and invasive neoplasm of the cervix and associated pathologies among the women with uterine prolapse in rural women of North India. Clin Cancer Investig J. 2016;5:110. https://doi.org/10.4103/2278-0513.178062.

Duhan N, Kadian YS, Sangwan N, et al. Uterovaginal prolapse and cervical cancer: a coincidence or an association. J Gynecol Surg. 2008;24:145–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/gyn.2008.B-02316.

Elbiaa AAM, Abdelazim IA, Farghali MM, et al. Unexpected premalignant gynecological lesions in women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for utero-vaginal prolapse. Prz Menopauzalny. 2015;14:188–91. https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2015.54344.

Foust-Wright C, Weinstein MM, Pilliod R, Posthuma R, Wakamatsu MM, Pulliam SJ. Uterine pathology in hysterectomies performed for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):S321.

Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, Barber MD. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

Gabriel I, Raju C, Lazarou G, et al. Factors affecting contained specimen manual extraction after robotic assisted laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy during pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3752-x.

Hill AJ, Carroll AW, Matthews CA. Unanticipated uterine pathologic finding after morcellation during robotic-assisted supracervical hysterectomy and cervicosacropexy for uterine prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:113–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0b013e31829ff5b8.

Leopold B, Kilts T, Borowsky M. The rate of incidental uterine malignant and premalignant lesions at supracervical hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.03.183.

Mahajan G, Kotru M, Batra M, et al. Usefulness of histopathological examination in uterine prolapse specimens. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51:403–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01337.x.

Mahnert N, Morgan D, Campbell D, et al. Unexpected gynecologic malignancy diagnosed after hysterectomy performed for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:397–405. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000642.

Mingels MJJM, Geels YP, Pijnenborg JMA, et al. Histopathologic assessment of the entire endometrium in asymptomatic women. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2013.05.011.

Mizrachi Y, Tannus S, Bar J, et al. Unexpected significant uterine pathological findings at vaginal hysterectomy despite unremarkable preoperative workup. Isr Med Assoc J. 2017;19:631–4.

Müezzinoǧlu B, Doǧer E, Yildiz DK. The pathologic spectrum of prolapsus uteri: histopathologic evaluation of hysterectomy specimens. J Gynecol Surg. 2005;21:133–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/gyn.2005.21.133.

Ouldamer L, Rossard L, Arbion F, et al. Risk of incidental finding of endometrial Cancer at the time of hysterectomy for benign condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:131–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2013.08.002.

Pandey D, Sehgal K, Kar G. Is it worth preserving the uterus? Risk of missing a malignancy in pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1258. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.igc.0000457075.08973.89.

Pendergrass M, Osmundsen B. Unanticipated pathology in the uterine specimen at the time of robotic Sacrocolpopexy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:S55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2013.08.178.

Ramm O, Gleason JL, Segal S, et al. Utility of preoperative endometrial assessment in asymptomatic women undergoing hysterectomy for pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:913–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1694-2.

Renganathan A, Edwards R, Duckett JRA. Uterus conserving prolapse surgery-what is the chance of missing a malignancy? Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:819–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1101-9.

Schouwink MH, van de Molengraft FJ, Roex AJ. Little clinical relevance in routine pathological examination of uteri removed in women with prolapse symptoms. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1997;141:678–81.

Sioulas V, Skarpas P, Chrelias C, et al. Hysterectomy for uterine prolapse: the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in asymptomatic postmenopausal women. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21.

Thavarasah AS. Incidental pathology at vaginal hysterectomy and repair: (a study of 750 cases). Ceylon Med J. 1976;21:248–51.

Vallabh-Patel V, Saiz C, Salamon C, et al. Prevalence of occult malignancy within Morcellated specimens removed during laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22:190–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000257.

Von Bargen EC, Grimes CL, Mishra K, et al. Prevalence of occult pre-malignant or malignant pathology at the time of uterine morcellation for benign disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2017;137:123–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12111.

Wan OYK, Cheung RYK, Chan SSC, Chung TKH. Risk of malignancy in women who underwent hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:190–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12033.

Wilkie GL, Reus E, Leung K, et al. Occult malignancy incidence and preoperative assessment in hysterectomies with Morcellation. J Gynecol Surg. 2018;34:18–26. https://doi.org/10.1089/gyn.2017.0036.

Yin H, Mittal K. Incidental findings in uterine prolapse specimen: frequency and implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:26–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pgp.0000101142.79462.be.

Public Health England Guidance Cervical screening: programme and colposcopy management (5th February 2020)

Jacobs I, Gentry-Maharaj A, Burnell M, Manchanda R, Singh N, Sharma A, et al. Sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasound screening for endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women: a case-control study within the UKCTOCS cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2010;12(1):38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70268-0.

Dijkhuizen FP, Mol BW, Brölmann HA, Heintz AP. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in the diagnosis of patients with endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2000;89(8):1765–72.

McPencow AM, Erekson EA, Guess MK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of endometrial evaluation prior to morcellation in surgical procedures for prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 209:22.e1-22.e9. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.03.033.

Loganathan J, Pradhan A. Laparoscopic and sacrospinous hysteropexy: a 5- year retrospective review in a tertiary UK Hospital. BJOG. 2019;126:237. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.22_15703.

Acknowledgments

Jergen Berens, translation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

• Nicholson: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Data analysis, Manuscript writing/editing.

• Khunda: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Data analysis, Manuscript writing/editing.

• Ballard: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Manuscript writing/editing.

• Rees: Data analysis and manuscript writing/editing.

• McCormick: Literature search, Data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial disclaimers/conflict of interest

Rachel Nicholson: None.

Aethele Khunda: Educational travel grant and/or speaker fees from Medtronic, Astellas, Axonic, Olympus and international conference organization committees.

Paul Ballard: Educational travel grant and/or speaker fees from Medtronic and Olympus.

Jon Rees: None.

Carol McCormick: None.

Additional information

Conference Presentations

BSUG, RCOG London, 3/10/2019–4/10/2019

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nicholson, R.C., Khunda, A., Ballard, P. et al. Prevalence of histological abnormalities in hysterectomy specimens performed for prolapse. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 32, 3131–3141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04858-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04858-z