Abstract

Background

Repeated-sprint training in hypoxia (RSH) is a recent intervention regarding which numerous studies have reported effects on sea-level physical performance outcomes that are debated. No previous study has performed a meta-analysis of the effects of RSH.

Objective

We systematically reviewed the literature and meta-analyzed the effects of RSH versus repeated-sprint training in normoxia (RSN) on key components of sea-level physical performance, i.e., best and mean (all sprint) performance during repeated-sprint exercise and aerobic capacity (i.e., maximal oxygen uptake [\(\dot{V}{\text{O}}_{2\hbox{max} }\)]).

Methods

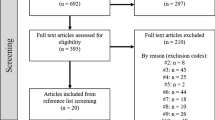

The PubMed/MEDLINE, SportDiscus®, ProQuest, and Web of Science online databases were searched for original articles—published up to July 2016—assessing changes in physical performance following RSH and RSN. The meta-analysis was conducted to determine the standardized mean difference (SMD) between the effects of RSH and RSN on sea-level performance outcomes.

Results

After systematic review, nine controlled studies were selected, including a total of 202 individuals (mean age 22.6 ± 6.1 years; 180 males). After data pooling, mean performance during repeated sprints (SMD = 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.02 to 0.93; P = 0.05) was further enhanced with RSH when compared with RSN. Although non-significant, additional benefits were also observed for best repeated-sprint performance (SMD = 0.31, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.89; P = 0.30) and \(\dot{V}{\text{O}}_{2\hbox{max} }\) (SMD = 0.18, 95% CI −0.25 to 0.61; P = 0.41).

Conclusion

Based on current scientific literature, RSH induces greater improvement for mean repeated-sprint performance during sea-level repeated sprinting than RSN. The additional benefit observed for best repeated-sprint performance and \(\dot{V}{\text{O}}_{2\hbox{max} }\) for RSH versus RSN was not significantly different.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hopkins WG, Hawley JA, Burke LM. Design and analysis of research on sport performance enhancement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(3):472–85.

Wilber RL. Application of altitude/hypoxic training by elite athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(9):1610–24.

Millet GP, Roels B, Schmitt L, et al. Combining hypoxic methods for peak performance. Sports Med. 2010;40(1):1–25.

Levine BD, Stray-Gundersen J. “Living high-training low”: effect of moderate-altitude acclimatization with low-altitude training on performance. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83(1):102–12.

Millet GP, Faiss R, Brocherie F, et al. Hypoxic training and team sports: a challenge to traditional methods? Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(Suppl 1):i6–7.

Girard O, Amann M, Aughey R, et al. Position statement–altitude training for improving team-sport players’ performance: current knowledge and unresolved issues. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(Suppl 1):i8–16.

Girard O, Brocherie F, Millet GP. On the use of mobile inflatable hypoxic marquees for sport-specific altitude training in team sports. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(Suppl 1):i121–3.

Faiss R, Girard O, Millet GP. Advancing hypoxic training in team sports: from intermittent hypoxic training to repeated sprint training in hypoxia. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(Suppl 1):i45–50.

Faiss R, Leger B, Vesin JM, et al. Significant molecular and systemic adaptations after repeated sprint training in hypoxia. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56522.

Kawada S, Ishii N. Changes in skeletal muscle size, fibre-type composition and capillary supply after chronic venous occlusion in rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2008;192(4):541–9.

Ishihara A, Itho K, Itoh M, et al. Hypobaric-hypoxic exposure and histochemical responses of soleus muscle fibers in the rat. Acta Histochem. 1994;96(1):74–80.

Mounier R, Pedersen BK, Plomgaard P. Muscle-specific expression of hypoxia-inducible factor in human skeletal muscle. Exp Physiol. 2010;95(8):899–907.

Levine BD, Stray-Gundersen J. Dose-response of altitude training: how much altitude is enough? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;588:233–47.

Wilber RL, Stray-Gundersen J, Levine BD. Effect of hypoxic “dose” on physiological responses and sea-level performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(9):1590–9.

Semenza GL, Shimoda LA, Prabhakar NR. Regulation of gene expression by HIF-1. Novartis Found Symp. 2006;272:2–8 (discussion 8–14, 33–6).

Calbet JA, Lundby C. Air to muscle O2 delivery during exercise at altitude. High Alt Med Biol. 2009;10(2):123–34.

Hoppeler H, Vogt M. Muscle tissue adaptations to hypoxia. J Exp Biol. 2001;204(Pt 18):3133–9.

Lundby C, Calbet JA, Robach P. The response of human skeletal muscle tissue to hypoxia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(22):3615–23.

McLean BD, Gore CJ, Kemp J. Application of ‘live low-train high’ for enhancing normoxic exercise performance in team sport athletes. Sports Med. 2014;44(9):1275–87.

Lundby C, Robach P. Does ‘altitude training’ increase exercise performance in elite athletes? Exp Physiol. 2016;101(7):783–8.

Millet GP, Brocherie F, Faiss R, et al. Clarification on altitude training [letter]. Exp Physiol. 2017;102(1):130–1.

Montero D, Lundby C. Enhanced performance after repeated sprint training in hypoxia: false or reality? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(11):2483.

Faiss R, Holmberg HC, Millet GP. Response [letter]. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(11):2484.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Girard O, Mendez-Villanueva A, Bishop D. Repeated-sprint ability—part I: factors contributing to fatigue. Sports Med. 2011;41(8):673–94.

Bishop D, Girard O, Mendez-Villanueva A. Repeated-sprint ability—part II: recommendations for training. Sports Med. 2011;41(9):741–56.

Taylor J, Macpherson T, Spears I, et al. The effects of repeated-sprint training on field-based fitness measures: a meta-analysis of controlled and non-controlled trials. Sports Med. 2015;45(6):881–91.

Gist NH, Fedewa MV, Dishman RK, et al. Sprint interval training effects on aerobic capacity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014;44(2):269–79.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Goods PS, Dawson B, Landers GJ, et al. No additional benefit of repeat-sprint training in hypoxia than in normoxia on sea-level repeat-sprint ability. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14(3):681–8.

Montero D, Lundby C. Repeated sprint training in hypoxia versus normoxia does not improve performance: a double-blind and cross-over study. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2015-0691 (Epub 2016 Aug 24).

Brocherie F, Millet GP, Hauser A, et al. “Live high-train low and high” hypoxic training improves team-sport performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(10):2140–9.

Brocherie F, Girard O, Faiss R, et al. High-intensity intermittent training in hypoxia: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled field study in youth football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(1):226–37.

Galvin HM, Cooke K, Sumners DP, et al. Repeated sprint training in normobaric hypoxia. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(Suppl 1):i74–9.

Gatterer H, Philippe M, Menz V, et al. Shuttle-run sprint training in hypoxia for youth elite soccer players: a pilot study. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13(4):731–5.

Kasai N, Mizuno S, Ishimoto S, et al. Effect of training in hypoxia on repeated sprint performance in female athletes. Springerplus. 2015;4:310.

Faiss R, Willis S, Born DP, et al. Repeated double-poling sprint training in hypoxia by competitive cross-country skiers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(4):809–17.

Casey DP, Joyner MJ. Compensatory vasodilatation during hypoxic exercise: mechanisms responsible for matching oxygen supply to demand. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 24):6321–6.

Gonzalez-Alonso J, Mortensen SP, Dawson EA, et al. Erythrocytes and the regulation of human skeletal muscle blood flow and oxygen delivery: role of erythrocyte count and oxygenation state of haemoglobin. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 1):295–305.

Cleland SM, Murias JM, Kowalchuk JM, et al. Effects of prior heavy-intensity exercise on oxygen uptake and muscle deoxygenation kinetics of a subsequent heavy-intensity cycling and knee-extension exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37(1):138–48.

McDonough P, Behnke BJ, Padilla DJ, et al. Control of microvascular oxygen pressures in rat muscles comprised of different fibre types. J Physiol. 2005;563(Pt 3):903–13.

Calbet JA, Lundby C. Skeletal muscle vasodilatation during maximal exercise in health and disease. J Physiol. 2012;590(24):6285–96.

Hellsten Y, Hoier B. Capillary growth in human skeletal muscle: physiological factors and the balance between pro-angiogenic and angiostatic factors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(6):1616–22.

Ridnour LA, Isenberg JS, Espey MG, et al. Nitric oxide regulates angiogenesis through a functional switch involving thrombospondin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(37):13147–52.

Bogdanis GC, Nevill ME, Boobis LH, et al. Contribution of phosphocreatine and aerobic metabolism to energy supply during repeated sprint exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80(3):876–84.

Westerblad H, Allen DG, Lannergren J. Muscle fatigue: lactic acid or inorganic phosphate the major cause? News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:17–21.

Endo M, Okada Y, Rossiter HB, et al. Kinetics of pulmonary VO2 and femoral artery blood flow and their relationship during repeated bouts of heavy exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;95(5–6):418–30.

Leger LA, Boucher R. An indirect continuous running multistage field test: the Universite de Montreal track test. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1980;5(2):77–84.

Bangsbo J, Iaia FM, Krustrup P. The Yo–Yo intermittent recovery test: a useful tool for evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Med. 2008;38(1):37–51.

Brocherie F, Millet GP, Girard O. Psycho-physiological responses to repeated-sprint training in normobaric hypoxia and normoxia. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2016-0052 (Epub 2016 Aug 24).

Dupont G, Blondel N, Berthoin S. Performance for short intermittent runs: active recovery vs. passive recovery. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89(6):548–54.

Rampinini E, Connolly DR, Ferioli D, et al. Peripheral neuromuscular fatigue induced by repeated-sprint exercise: cycling vs. running. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2016;56(1):49–59.

Girard O, Racinais S, Kelly L, et al. Repeated sprinting on natural grass impairs vertical stiffness but does not alter plantar loading in soccer players. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(10):2547–55.

Brocherie F, Millet GP, Girard O. Neuro-mechanical and metabolic adjustments to the repeated anaerobic sprint test in professional football players. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(5):891–903.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

Franck Brocherie, Olivier Girard, Raphaël Faiss, and Grégoire P. Millet declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this review.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brocherie, F., Girard, O., Faiss, R. et al. Effects of Repeated-Sprint Training in Hypoxia on Sea-Level Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 47, 1651–1660 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0685-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0685-3