Abstract

Objectives

To describe aerobic physical activity among middle-aged and older adults by their selfreported cognitive decline and their receipt of informal care for declines in cognitive functioning and most common type of physical activity.

Design

Cross-sectional study using data from the 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Setting

Landline and cellular telephone survey.

Participants

93,082 respondents aged 45 years and older from 21 US states in 2011.

Measurements

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) was defined as experiencing confusion or memory loss that was happening more often or getting worse during the past 12 months. Regular care was defined as always, usually, or sometimes receiving care from family or friends because of SCD. Using the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, respondents were classified as being inactive, insufficiently active, or sufficiently active based on their reported aerobic exercise. We calculated weighted proportions and used chi-square tests for differences across categories by SCD status and receipt of care. We estimated the prevalence ratio (PR) for being inactive, insufficiently active, and sufficiently active using separate log-binomial regression models, adjusting for covariates.

Results

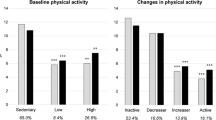

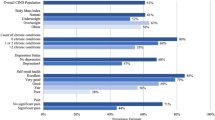

12.3% of respondents reported SCD and 23.1% of those with SCD received regular care. 29.6% (95%CI: 28.9-30.4) of respondents without SCD were inactive compared to 37.1% (95%CI: 34.7-39.5) of those with SCD who did not receive regular care and 50.2% (95%CI: 45.2-55.1) of those with SCD who received regular care. 52.4% (95%CI: 51.6-53.2) of respondents without SCD were sufficiently active compared to 46.4% (95%CI: 43.8-49.0) of respondents with SCD and received no regular care and 30.6% (95%CI: 26.1-35.6) of respondents with SCD who received regular care. After adjusting for demographic and health status differences, people receiving regular care for SCD had a significantly lower prevalence of meeting aerobic guidelines compared to people without SCD (PR=0.80, 95%CI: 0.69-0.93, p=0.005). The most prevalent physical activity was walking for adults aged ≥ 45 years old (41-52%) regardless of SCD status or receipt of care.

Conclusion

Overall, the prevalence of inactivity was high, especially among people with SCD. These findings suggest a need to increase activity among middle-aged and older adults, particularly those with SCD who receive care. Examining ways to increase walking, potentially by involving informal caregivers, could be a promising way for people with SCD to reduce inactivity and gain the health benefits associated with meeting physical activity guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The National Institute of Aging (NIA), 2015. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/healthy-aging-lessons-baltimore-longitudinal-study-aging/what-does-allmean-you. Accessed 9 January 2016

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2008. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, October 2008. ODPHP Publication No. U0036. http://health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf. Accessed 19 August 2015

Sun F, Norman IJ, While AE. Physical activity in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13:449. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-449

Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Park H, Yoshida D, Uemura K, Tsutsumimoto K, Liu-Ambrose T, Suzuki T. Poor balance and lower gray matter volume predict falls in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. BMC Neurology 2013;13:102

Winter H, Watt K, Peel NM. Falls prevention interventions for community-dwelling older persons with cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2013;25(2): 215–227

Taylor ME, Delbaere K, Lord SR, Mikolaizak AS, Close JCT. Physical impairments in cognitively impaired older people: implications for risk of falls. Int Psychogeriatr 2013;25(1): 148–156

Morris MT. Epidemiology of falls. Age Ageing 2001;30(Suppl4):3–7

Muir SW, Gopaul K, Montero-Odasso MM, 2012. The role of cognitive impairment in fall risk among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2012;41(3): 299–308

Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “It’s always a trade-off”. JAMA 2010;303: 258–266

Proper KI, Singh AS, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Sedentary behaviors and health outcomes among adults: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am J Prev Med 2011;40(2): 174–182

Thorp AA, Owen N, Neuhaus M, Dunstan DW. Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults a systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996-2011. Am J Prev Med 2011;41(2): 207–215

Edwardson CL, Gorely T, Davies MJ et al. Association of sedentary behaviour with metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7(4):e34916

Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010;38: 105–113

Tomas-Zapico C, Iglesias-Gutierrez E, Fernandez-Garcia B, de Gonzalo-Calvo D. Physical activity as healthy intervention against severe oxidative stress in elderly population. J Frailty Aging 2013;2(3): 135–143

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 2015. The Surgeon General’s recent Call to Action released in 2015 (Step it Up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities). Accessed http://www. surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/walking-and-walkable-communities/

Prohaska TR, Eisenstein AR, Satariano WA, Hunter R, Bayles CM, Kurtovich E, Kealey M, Ivey SL. Walking and the preservation of cognitive function in older populations. Gerontologist 2009;49(S1):S86–S93. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp079

Abbott RD, White LR, Ross GW, Masaki KH, Curb JD, Petrovitch H. Walking and dementia in physically capable elderly men. JAMA 2004;292: 1447–1453

Adams ML, Deokar AJ, Anderson LA, Edwards VJ. Self-reported increased confusion or memory loss and associated functional difficulties among adults aged =60 years -21 States, 2011. MMWR 2013;62(18): 347–350

Alzheimer’s Disease International: World Alzheimer’s Report 2010, 2011. The global economic impact of dementia. London 52. Available from: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/files/WorldAlzheimerReport2010.pdf

Wimo A, Prince M. World Alzheimer report 2010: the global economic impact of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International 21 September 2010

Shaw FE, Kenny RA. Can falls in patients with dementia be prevented? Age Ageing 1998;27: 7–9

Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Buchman AS, et al. Lower extremity motor function and disability in mild cognitive impairment. Exp Aging Res. 2007;33: 355–371

Pettersson AF, Olsson E, Wahlund LO. Motor function in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;19: 299–304

Tangen CG, Engedal K, Bergland A, Moger TA, Mengshoel AM. Relationships between balance and cognition in patients with subjective cognitive impairment, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer disease. Physical Therapy 2014;94(8); 1123–1134

Waite LM, Broe GA, Grayson DA, Creasey H. Motor function and disability in the dementias. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2000;15: 897–903

Young J, Angevaren M, Rusted J, Tabet N. Aerobic exercise to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015;4. Art. No.: CD005381. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005381. pub4

Angevaren M, Aufdemkampe G, Verhaar HJJ, Aleman A, Vanhees L. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008;2. Art. No.: CD005381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005381.pub2

Hau C, Reid KF, Wong KF, Chin RJ, Botto TJ, Eliasziw, M, Bermudez OI, Fielding RA. Collaborative evaluation of the healthy habits program: an effective community intervention to improve mobility and cognition of Chinese older adults living in the U.S. J Nutr Health Aging 2016;20(4): 391–397

Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update, the growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. AARP Public Policy Institute Insight 51. Washington, DC: AARP

Coughlin J. Estimating the impact of caregiving and employment on well-being. Outcomes & Insights in Health Management. 2010;2(1)

Mokdad AH. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30: 43–54

BRFSS 2011 Summary Data Quality Report, Version #5—Revised: 2/04/2013. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2011/pdf/2011_summary_data_quality_report.pdf. Accessed 2 October 2015

CDC Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. A data users guide to the BRFSS physical activity questions: how to assess the 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/pdf/PA%20RotatingCore_ BRFSSGuide_508Comp_07252013FINAL.pdf. Accessed 19 August 2015

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. Disability and Health Data System. Data Guide–Limitation Status. Available at http://dhds.cdc.gov/guides/limitation

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Adult BMI. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/. Accessed 23 May 2016

World Help Organization. Global Database on Body Mass Index: An interactive surveillance tool for monitoring nutrition transition. Available at: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html. Accessed 23 May 2016

Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21

World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland; 2002. Available at: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 22 January 2016

CDC Division of Behavioral Surveillance, 2013. Preparing 2011 BRFSS module data for analysis. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2011/pdf/brfss2011_analysis.pdf. Accessed 19 August 2015

Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, Bowen PE, Connolly, ES, Cox NJ, Dunbar-Jacob JM, Granieri EC, Hunt G, McGarry K, Patel D, Potosky AL, Sanders-Bush E, Silberberg D, Trevisan M. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Preventing Alzheimer Disease and cognitive decline. Ann Intern Med 2010;153: 176–181

Szanton SL, Walker RK, Roberts L, Thorpe RJ, Wolff J, Agree E, Roth DL, Gitlin LN, Seplaki C. Older adults’ favorite activities are resoundingly active: findings from the NHATS study. Geriatric Nursing 2015;36(2): 131–135

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed 19 August 2015

Clarke P, Ailshire JA, Lantz P. Urban built environments and trajectories of mobility disability: Findings from a national sample of community-dwelling American adults (1986-2001). Social Science & Medicine 2009;69(6): 964–970. doi: 10.1016/j. socscimed.2009.06.041

King D. Neighborhood and individual factors in activity in older adults: results from the neighborhood and senior health study. J Aging Phys Act. 2008;16: 144–170

Rosenberg DE, Huang DL, Simonovich SD, Belza B. Outdoor built environment barriers and facilitators to activity among midlife and older adults with mobility disabilities. Gerontologist 2013;53(2): 268–279

Li W, Keegan TH, Sternfeld B, Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Kelsey JL. Outdoor falls among middle-aged and older adults: a neglected public health problem. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Am J Public Health 2006;96(7): 1192–1200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083055

Hunter RH, Potts S, Beyerle R, Stollof E, Lee C, Duncan R, Vandenberg A, Belza B, Marquez DX, Friedman DB, Bryant LL, 2013. Pathways to better community wayfinding. Seattle, WA; Washington, DC. CDC Healthy Aging Research Network and Easter Seals Project ACTION. http://www.prc-han.org.

Marquez DX, Hunter RH, Griffith MH, Brynant LL, Janicek SJ, Atherly AJ. Older adult strategies for community wayfinding. J Appl Gerontol, 2015. doi: 0733464815581481

Vandenberg AE, Hunter RH, Anderson LA, Bryant LL, Hooker S, Satariano W. Walking and walkability: is wayfinding a missing link? Implications for public health practice. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(2): 189–197

Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Bacak SJ, Housemann RA. The epidemiology of walking for physical activity in the United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35(9): 1529–36

Belza B, Allen P, Brown DR, Farren L, Janicek S, Jones DL, King DK, Marquez DX, Miyawaki CE, Rosenberg D. Mall walking: a program resource guide. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Health Promotion Research Center;2015. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/downloads/mallwalking-guide.pdf

Duncan HH, Travis SS, McAuley WJ. An emergent theoretical-model for interventions encouraging physical-activity (mall-walking) among older adults. J Appl Gerontol 1995;14(1): 64–77

Farren L, Belza B, Allen P, Brolliar S, Brown DR, Cormier SCD et al. Mall walking program environments, features, and participants: a scoping review. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:150027. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150027

Arkin SM. Elder rehab: a student-supervised exercise program for Alzheimer’s patients. Gerontologist 1999;39(6): 729–735

Arkin SM. Student-led exercise sessions yield significant fitness gains for Alzheimer’s patients. Am J Alzheimer Dis Other Demen 2003;18(3): 159–170

Heyn P, Abreu B, Ottenbacher K. The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85: 1694–1704

Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Teri L. A home health care approach to exercise for persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Care Manag J 2005;6(2): 90–97

Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290(15): 2015–2022

Venturelli M, Scarsini R, Schen F. Six-month walking program changes cognitive and ADL performance in patients with Alzheimer. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2011;26(5): 381–388. doi: 10.1177/1533317511418956

Tappen RM, Roach KE, Applegate EB, Stowell P. Effect of a combined walking and conversation intervention on functional mobility of nursing home residents with Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2000;14(4): 196–201

Farias ST, Mungas D, Jaqust W. Degree of discrepancy between self and other-reported everyday functioning by cognitive status: dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy elders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20(9): 827–834

Administration on Aging. A Profile of Older Americans: 2011. Available at: http://www.aoa.acl.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2011/6.aspx. Accessed 22 January 2016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Table 1

List of categorized aerobic activities, metabolic equivalent (MET) values by activity, and number and weighted percent of respondents aged 45 years and older who reported each activity, by subjective cognitive decline (SCD) status and receipt of regular informal care for SCD†, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2011

Supplementary Table 2

Weighted percentage of respondents aged 45 years and older who met physical activity guidelines for aerobic activity and muscle strengthening activity by subjective cognitive decline (SCD) status and receipt of regular informal care for SCD†, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2011

Supplementary Table 3

Association between subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and receipt of care for SCD† with being inactive, insufficiently active, and sufficiently active in adjusted weighted logistic regression models among adults aged 45 years and older, by BMI category*, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2011

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miyawaki, C.E., Bouldin, E.D., Kumar, G.S. et al. Associations between physical activity and cognitive functioning among middle-aged and older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 21, 637–647 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0835-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0835-6