Abstract

Background

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Reducing the disease burden requires an understanding of factors associated with the prevention and management of CHD. Literacy skills may be one such factor.

Objectives

To examine the independent and interactive effects of four literacy skills: reading, numeracy, oral language (speaking) and aural language (listening) on calculated 10-year risk of CHD and to determine whether the relationships between literacy skills and CHD risk were similar for men and women.

Design

We used multivariable linear regression to assess the individual, combined, and interactive effects of the four literacy skills on risk of CHD, adjusting for education and race.

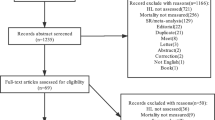

Participants

Four hundred and nine English-speaking adults in Boston, MA and Providence, RI.

Measures

Ten-year risk of coronary heart disease was calculated using the Framingham algorithm. Reading, oral language and aural language were measured using the Woodcock Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Numeracy was assessed through a modified version of the numeracy scale by Lipkus and colleagues.

Key Results

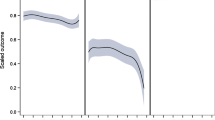

When examined individually, reading (p = 0.007), numeracy (p = 0.001) and aural language (p = 0.004) skills were significantly associated with CHD risk among women; no literacy skills were associated with CHD risk in men. When examined together, there was some evidence for an interaction between numeracy and aural language among women suggesting that higher skills in one area (e.g., aural language) may compensate for difficulties in another resulting in an equally low risk of CHD.

Conclusions

Results of this study not only provide important insight into the independent and interactive effects of literacy skills on risk of CHD, they also highlight the need for the development of easy-to use assessments of the oral exchange in the health care setting and the need to better understand which literacy skills are most important for a given health outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mensah GA, Brown DW. An overview of cardiovascular disease burden in the United States. Health Aff. 2007;26(1):38–48.

The World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases. Available at: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/. Accessed August, 2010.

Department of Hhealth and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US. Government Printing Office; 2000.

Ratzan S, Parker R. Introduction. In: Selden C, Zorn M, Ratzan S, Parker R, eds. National library of medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

Kirsch I. The international adult literacy survey (IALS): Understanding what was measured. Princeton, NJ: Statistics and Research Division of the Educational Testing Service; December 2001. RR-01-25.

Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkinds L, Kolstad A. Adult literacy in America: A first look at the results of the national adult literacy survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education; 1993.

Dolan N, Ferreira M, Davis TC, et al. Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among veterans: Does literacy make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2617–22.

Chew L, Bradley K, Flum D, Cornia P, Koepsell TD. The impact of low health literacy on surgical practice. Am J Surg. 2004;188(3):250–3.

Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):847–51.

Kripalani S, Henderson L, Chiu E, Robertson R, Kolm P, Jacobson T. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):852–6.

National Center for Education Statistics. The health literacy of America's adults: Results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education;2006.

Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167(14):1503.

Fredrickson D, Washington R, Pham N, Jackson T, Wiltshire J, Jecha L. Reading grade levels and health behaviors of parents at child clinics. Kansas Med. 1995;96:127–9.

Hawthorne G. Preteenage drug use in Australia: The key predictors and school-based drug education. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:384–95.

Battersby C, Hartley K, Fletcher A, Markowe H, Brown R, Styles W. Cognitive function in hypertension: A community based study. J Hum Hypertens. 1993;7:117–23.

Williams M, Baker D, Parker R, Nurss J. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients' knowledge of their chronic disease: A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158(2):166–72.

Doak C, Doak L, Root J. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott; 1996.

Weiss BD. Communicating with patients who cannot read. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;337(4):272–4.

Niswander KR, Gordon M. The women and their pregnancies: The collaborative perinatal study of the national institute of neurological diseases and stroke. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Health; 1972.

Gilman S, Martin L, Abrams D, et al. Educational attainment and smoking: A causal association? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008;37(3):615–24.

Sullivan L, Massaro J, D'Agostino R. Presentation of multivariate data for clinincal use: The Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat. Med. 2004;23(10):1631–60.

Wilson P, D'Agostino R, Levy D, Belanger A, Sibershatz H, Kannel W. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–47.

D'Agostino R, Grundy S, Sullivan L, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham Coronary Heart Disease prediction scores - results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286(2):180–7.

Allain C, Poon L, Chan C, Richmond W, Fu P. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1974;20(4):470–5.

Rifai N, Cole T, Iannotti E, et al. Assessment of interlaboratory performance in external proficiency testing programs with a direct hdl-cholesterol assay. Clin Chem. 1988;44(7):1452–8.

Mattu G, Heran B, Wright J. Overall accuracy of the BpTRU–an automated electronic blood pressure device. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9(1):47–52.

Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Technical manual: Woodcock-Johnson III. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001.

Lipkus IM, Samsa G, Rimer BK. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples. Med. Decis. Making. 2001;21(1):37–44.

Schwartz L, Woloshin S, Black W, Welch G. The role of numeracy in understanding the benefit of screening mammography. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997;127:966–71.

Graubard B, Korn E. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):652–9.

Barry W, Feldman S. Multiple regression in practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1985.

McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:29–48.

Loucks E, Rehkopf D, Thurston R, Kawachi I. Socioeconomic disparities in metabolic syndrome differ by gender: Evidence from NHANES III. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007;17:19–26.

Gunderson E, Lewis C, Murtaugh M, Quesenberry C, Smith West D, Sidney S. Long-term plasma lipid changes associated with a first birth: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1028–39.

Gunderson E, Murtaugh M, Lewis C, Quesenberry C, West D, Sidney S. Excess gains in weight and waist circumference associated with childbearing: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA). Int. J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:525–35.

Mathews T, Venura S. Birth and fertility rates by educational attainment: United States, 1994. Vital Stat Rep (Suppl). 1997;45:100–7.

Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by NHLBI grant 1R21HL094297-01 (Martin)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1557-9

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, L.T., Schonlau, M., Haas, A. et al. Literacy Skills and Calculated 10-Year Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 45–50 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1488-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1488-5