Abstract

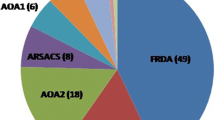

While Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA) and ataxia telangiectasia (AT) are known to be the two most frequent forms of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia (ARCA), knowledge on the other forms of ARCA has been obtained only recently, and they appear to be rarer. Little is known about the epidemiological features and the relative frequency of the ARCAs and only few data are available about the comparative features of ARCAs. We prospectively studied 102 suspected ARCA cases from Eastern France (including 95 from the Alsace region) between 2002 and 2008. The diagnostic procedure was based on a sequential strategic scheme. We examined the clinical, paraclinical and molecular features of the large cohort of patients and compared features and epidemiology according to molecular diagnosis. A molecular diagnosis could be established for 57 patients; 36 were affected with FRDA, seven with ataxia plus oculomotor apraxia type 2 (AOA2), four with AT, three with ataxia plus oculomotor apraxia type 1 (AOA1), three with Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome, two with autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay (ARSACS), one with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED) and one with autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 2 (ARCA2). The group of patients with no identified mutation had a significantly lower spinocerebellar degeneration functional score corrected for disease duration (SDFS/DD ratio; p = 0.002) and comprised a significantly higher proportion of cases with onset after 20 years (p < 0.01). Extensor plantar reflexes were rarer and cerebellar atrophy was more frequent in the group of patients with a known non-Friedreich ARCA compared to all other patients (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0003, respectively). Lower limb areflexia and electroneuromyographic evidences of peripheral neuropathy were more frequent in the Friedreich ataxia group than in the group with a known non-Friedreich ataxia and were more frequent in the later group than in the group with no identified mutation (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.01, respectively). The overall prevalence of ARCA in Alsace is 1/19,000. We can infer the prevalence of FRDA in Alsace to be 1/50,000 and infer that AT is approximately eight times less frequent than FRDA. MSS, AOA2 and ARSACS appear only slightly less frequent than AT. Despite the broad variability of severity, Friedreich ataxia patients are clinically distinct from the other forms of ARCA. Patients with no identified mutation have more often a pure cerebellar degenerative disease or a spastic ataxia phenotype. It appears that ARCA cases can be divided into two major groups of different prognosis, an early-onset group with a highly probable genetic cause and an adult-onset group with better prognosis for which a genetic cause is more difficult to prove but not excluded. ARCAs are rare, early-disabling and genetically heterogeneous diseases dominated by FRDA. Several of the recently identified ARCAs, such as AVED, ARSACS, AOA1, AOA2 and MSS, have a prevalence close to AT and should be searched for extensively irrespective of ethnic origins. The strategic scheme is a useful tool for the diagnosis of ARCAs in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Koenig M (2003) Rare forms of autosomal recessive neurodegenerative ataxia. Semin Pediatr Neurol 10(3):183–192

Fogel BL, Perlman S (2007) Clinical features and molecular genetics of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias. Lancet Neurol 6(3):245–257

Durr A, Cossee M, Agid Y, Campuzano V, Mignard C, Penet C et al (1996) Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich's ataxia. N Engl J Med 335(16):1169–1175

Campuzano V, Montermini L, Molto MD, Pianese L, Cossee M, Cavalcanti F et al (1996) Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 271(5254):1423–1427. doi:10.1126/science.271.5254.1423

Savitsky K, Bar-Shira A, Gilad S, Rotman G, Ziv Y, Vanagaite L et al (1995) A single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase. Science 268(5218):1749–1753. doi:10.1126/science.7792600

Chun HH, Gatti RA (2004) Ataxia–telangiectasia, an evolving phenotype. DNA Repair (Amst) 3(8–9):1187–1196. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.010

Caldecott KW (2008 Aug) Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat Rev 9(8):619–631

Moreira MC, Klur S, Watanabe M, Nemeth AH, Le Ber I, Moniz JC et al (2004) Senataxin, the ortholog of a yeast RNA helicase, is mutant in ataxia–ocular apraxia 2. Nat Genet 36(3):225–227. doi:10.1038/ng1303

Takashima H, Boerkoel CF, John J, Saifi GM, Salih MA, Armstrong D et al (2002) Mutation of TDP1, encoding a topoisomerase I-dependent DNA damage repair enzyme, in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy. Nat Genet 32(2):267–272. doi:10.1038/ng987

Moreira MC, Barbot C, Tachi N, Kozuka N, Uchida E, Gibson T et al (2001) The gene mutated in ataxia–ocular apraxia 1 encodes the new HIT/Zn-finger protein aprataxin. Nat Genet 29(2):189–193. doi:10.1038/ng1001-189

Stewart GS, Maser RS, Stankovic T, Bressan DA, Kaplan MI, Jaspers NG et al (1999) The DNA double-strand break repair gene hMRE11 is mutated in individuals with an ataxia–telangiectasia-like disorder. Cell 99(6):577–587. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81547-0

Suraweera A, Becherel OJ, Chen P, Rundle N, Woods R, Nakamura J et al (2007) Senataxin, defective in ataxia oculomotor apraxia type 2, is involved in the defense against oxidative DNA damage. J Cell Biol 177(6):969–979. doi:10.1083/jcb.200701042

Lagier-Tourenne C, Tazir M, Lopez LC, Quinzii CM, Assoum M, Drouot N et al (2008) ADCK3, an ancestral kinase, is mutated in a form of recessive ataxia associated with coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Am J Hum Genet 82(3):661–672. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.024

Mollet J, Delahodde A, Serre V, Chretien D, Schlemmer D, Lombes A et al (2008) CABC1 gene mutations cause ubiquinone deficiency with cerebellar ataxia and seizures. Am J Hum Genet 82(3):623–630. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.022

Puccio H, Koenig M (2002) Friedreich ataxia: a paradigm for mitochondrial diseases. Curr Opin Genet Dev 12(3):272–277. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00298-8

Ben Hamida C, Doerflinger N, Belal S, Linder C, Reutenauer L, Dib C et al (1993) Localization of Friedreich ataxia phenotype with selective vitamin E deficiency to chromosome 8q by homozygosity mapping. Nat Genet 5(2):195–200. doi:10.1038/ng1093-195

Gabsi S, Gouider-Khouja N, Belal S, Fki M, Kefi M, Turki I et al (2001) Effect of vitamin E supplementation in patients with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency. Eur J Neurol 8(5):477–481. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00273.x http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11554913&dopt=Abstract

Ouahchi K, Arita M, Kayden H, Hentati F, Ben Hamida M, Sokol R et al (1995) Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency is caused by mutations in the alpha-tocopherol transfer protein. Nat Genet 9(2):141–145. doi:10.1038/ng0295-141 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=7719340&dopt=Abstract

Martinello F, Fardin P, Ottina M, Ricchieri GL, Koenig M, Cavalier L et al (1998) Supplemental therapy in isolated vitamin E deficiency improves the peripheral neuropathy and prevents the progression of ataxia. J Neurol Sci 156(2):177–179. doi:10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00038-0 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9588854&dopt=Abstract

Kohlschutter A, Hubner C, Jansen W, Lindner SG (1988) A treatable familial neuromyopathy with vitamin E deficiency, normal absorption, and evidence of increased consumption of vitamin E. J Inherit Metab Dis 11(Suppl 2):149–152. doi:10.1007/BF01804221 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=3141695&dopt=Abstract

Kayden HJ (1993) The neurologic syndrome of vitamin E deficiency: a significant cause of ataxia. Neurology 43(11):2167–2169 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=8232922&dopt=Abstract

Cavalier L, Ouahchi K, Kayden HJ, Di Donato S, Reutenauer L, Mandel JL et al (1998) Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency: heterogeneity of mutations and phenotypic variability in a large number of families. Am J Hum Genet 62(2):301–310. doi:10.1086/301699 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9463307&dopt=Abstract

Rustin P, von Kleist-Retzow JC, Chantrel-Groussard K, Sidi D, Munnich A, Rotig A (1999) Effect of idebenone on cardiomyopathy in Friedreich's ataxia: a preliminary study. Lancet 354(9177):477–479. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01341-0 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10465173&dopt=Abstract

Di Prospero NA, Baker A, Jeffries N, Fischbeck KH (2007) Neurological effects of high-dose idebenone in patients with Friedreich's ataxia: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 6(10):878–886. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70220-X http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17826341&dopt=Abstract

Hausse AO, Aggoun Y, Bonnet D, Sidi D, Munnich A, Rotig A et al (2002) Idebenone and reduced cardiac hypertrophy in Friedreich's ataxia. Heart 87(4):346–349. doi:10.1136/heart.87.4.346

Koht J, Tallaksen CM (2007) Cerebellar ataxia in the eastern and southern parts of Norway. Acta Neurol Scand 187:76–79. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00853.x

Nishizawa M (2001) Hereditary ataxias—overview. Rinsho shinkeigaku (Clin Neurol) 41(12):1114–1116

Zortea M, Armani M, Pastorello E, Nunez GF, Lombardi S, Tonello S et al (2004) Prevalence of inherited ataxias in the province of Padua, Italy. Neuroepidemiology 23(6):275–280. doi:10.1159/000080092

Rasmussen A, Gomez M, Alonso E, Bidichandani SI (2006) Clinical heterogeneity of recessive ataxia in the Mexican population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77(12):1370–1372. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.090449

Rotig A, Sidi D, Munnich A, Rustin P (2002) Molecular insights into Friedreich's ataxia and antioxidant-based therapies. Trends Mol Med 8(5):221–224. doi:10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02330-4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12067631&dopt=Abstract

Le Ber I, Bouslam N, Rivaud-Pechoux S, Guimaraes J, Benomar A, Chamayou C et al (2004) Frequency and phenotypic spectrum of ataxia with oculomotor apraxia 2: a clinical and genetic study in 18 patients. Brain 127(Pt 4):759–767. doi:10.1093/brain/awh080

Swift M, Morrell D, Cromartie E, Chamberlin AR, Skolnick MH, Bishop DT (1986) The incidence and gene frequency of ataxia–telangiectasia in the United States. Am J Hum Genet 39(5):573–583

Tavani F, Zimmerman RA, Berry GT, Sullivan K, Gatti R, Bingham P (2003) Ataxia–telangiectasia: the pattern of cerebellar atrophy on MRI. Neuroradiology 45(5):315–319

Wullner U, Klockgether T, Petersen D, Naegele T, Dichgans J (1993) Magnetic resonance imaging in hereditary and idiopathic ataxia. Neurology 43(2):318–325

Le Ber I, Brice A, Durr A (2005) New autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias with oculomotor apraxia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 5(5):411–417. doi:10.1007/s11910-005-0066-4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16131425&dopt=Abstract

Date H, Onodera O, Tanaka H, Iwabuchi K, Uekawa K, Igarashi S et al (2001) Early-onset ataxia with ocular motor apraxia and hypoalbuminemia is caused by mutations in a new HIT superfamily gene. Nat Genet 29(2):184–188. doi:10.1038/ng1001-184

Anttonen AK, Mahjneh I, Hamalainen RH, Lagier-Tourenne C, Kopra O, Waris L et al (2005) The gene disrupted in Marinesco–Sjogren syndrome encodes SIL1, an HSPA5 cochaperone. Nat Genet 37(12):1309–1311. doi:10.1038/ng1677

Engert JC, Berube P, Mercier J, Dore C, Lepage P, Ge B et al (2000) ARSACS, a spastic ataxia common in northeastern Quebec, is caused by mutations in a new gene encoding an 11.5-kb ORF. Nat Genet 2:120–125. doi:10.1038/72769

Manto MU (2005) The wide spectrum of spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs). Cerebellum 4(1):2–6. doi:10.1080/14734220510007914

Schols L, Bauer P, Schmidt T, Schulte T, Riess O (2004) Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: clinical features, genetics, and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol 3(5):291–304. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00737-9

Nagafuchi S, Yanagisawa H, Sato K, Shirayama T, Ohsaki E, Bundo M et al (1994) Dentatorubral and pallidoluysian atrophy expansion of an unstable CAG trinucleotide on chromosome 12p. Nat Genet 6(1):14–18. doi:10.1038/ng0194-14

Koide R, Ikeuchi T, Onodera O, Tanaka H, Igarashi S, Endo K et al (1994) Unstable expansion of CAG repeat in hereditary dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Nat Genet 6(1):9–13. doi:10.1038/ng0194-9

McDonald ME, Ambrose CM, Duyao MP et al (1993) A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group. Cell 72(6):971–983

Rampoldi L, Dobson-Stone C, Rubio JP, Danek A, Chalmers RM, Wood NW et al (2001) A conserved sorting-associated protein is mutant in chorea-acanthocytosis. Nat Genet 28(2):119–120. doi:10.1038/88821

Martin MH, Bouchard JP, Sylvain M, St-Onge O, Truchon S (2007) Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay: a report of MR imaging in 5 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28(8):1606–1608. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A0603

Anheim M, Chaigne D, Fleury M, Santorelli FM, De Seze J, Durr A et al (2008) Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay: study of a family and review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris) 164(4):363–368. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2008.02.001

Anheim M, Fleury MC, Franques J, Moreira MC, Delaunoy JP, Stoppa-Lyonnet D et al (2008) Clinical and molecular findings of ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2 in 4 families. Arch Neurol 65(7):958–962. doi:10.1001/archneur.65.7.958

Tranchant C, Fleury M, Moreira MC, Koenig M, Warter JM (2003) Phenotypic variability of aprataxin gene mutations. Neurology 60(5):868–870

Cossee M, Schmitt M, Campuzano V, Reutenauer L, Moutou C, Mandel JL et al (1997) Evolution of the Friedreich’s ataxia trinucleotide repeat expansion: founder effect and premutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94(14):7452–7457. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.14.7452

Epplen C, Epplen JT, Frank G, Miterski B, Santos EJ, Schols L (1997) Differential stability of the (GAA)n tract in the Friedreich ataxia (STM7) gene. Hum Genet 99(6):834–836. doi:10.1007/s004390050458

Schmitz-Hubsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, Berciano J, Boesch S, Depondt C et al (2006) Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology 66(11):1717–1720. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219042.60538.92

Yabe I, Matsushima M, Soma H, Basri R, Sasaki H (2008) Usefulness of the Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA). J Neurol Sci 266(1-2):164–166. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.09.021

Fahey MC, Corben L, Collins V, Churchyard AJ, Delatycki MB (2007) How is disease progress in Friedreich’s ataxia best measured? A study of four rating scales. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78(4):411–413. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.096008

du Montcel ST, Charles P, Ribai P, Goizet C, Le Bayon A, Labauge P et al (2008) Composite cerebellar functional severity score: validation of a quantitative score of cerebellar impairment. Brain 131(Pt 5):1352–1361. doi:10.1093/brain/awn059

Mascalchi M, Salvi F, Piacentini S, Bartolozzi C (1994) Friedreich’s ataxia: MR findings involving the cervical portion of the spinal cord. AJR Am J Roentgenol 163(1):187–191

Bhidayasiri R, Perlman SL, Pulst SM, Geschwind DH (2005) Late-onset Friedreich ataxia: phenotypic analysis, magnetic resonance imaging findings, and review of the literature. Arch Neurol 62(12):1865–1869. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.12.1865

Gros-Louis F, Dupre N, Dion P, Fox MA, Laurent S, Verreault S et al (2007) Mutations in SYNE1 lead to a newly discovered form of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. Nat Genet 39(1):80–85. doi:10.1038/ng1927

Dupre N, Gros-Louis F, Chrestian N, Verreault S, Brunet D, de Verteuil D et al (2007) Clinical and genetic study of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 1. Ann Neurol 62(1):93–98. doi:10.1002/ana.21143

Thiffault I, Tetreault M, Allyson J, Gosselin I, Loiselle L, Mathieu J, Bouchard JP, Lessage J, Brais B. Identification and characterization of a new locus responsible for recessive late-onset cerebellar ataxia (LOCA). ASHG San Diego, CA, 2007 Oct 23–27:355A [1825].

El Euch-Fayache G, Lalani I, Amouri R, Turki I, Ouahchi K, Hentati A et al (2003) Phenotypic features and genetic findings in sacsin related autosomal recessive ataxia in Tunisia. Arch Neurol 60:982–988

Criscuolo C, Banfi S, Orio M, Gasparini P, Monticelli A, Scarano V et al (2004) A novel mutation in SACS gene in a family from southern Italy. Neurology 62(1):100–102

Ogawa T, Takiyama Y, Sakoe K, Mori K, Namekawa M, Shimazaki H et al (2004) Identification of a SACS gene missense mutation in ARSACS. Neurology 62(1):107–109

Bouchard JP, Barbeau A, Bouchard R, Bouchard RW (1978) Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay. Can J Neurol Sci 5(1):61–69

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funds from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Scientifique, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg (PHRC régional to C.T.) and the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche-Maladies Rares (ANR-MRAR to M.K.). B. M. is supported by the GIS-Maladies Rares.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anheim, M., Fleury, M., Monga, B. et al. Epidemiological, clinical, paraclinical and molecular study of a cohort of 102 patients affected with autosomal recessive progressive cerebellar ataxia from Alsace, Eastern France: implications for clinical management. Neurogenetics 11, 1–12 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-009-0196-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-009-0196-y