Abstract

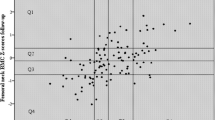

As the correlation of bone mass from childhood to adulthood is unclear, we conducted a long-term prospective observational study to determine if a pediatric bone mass scan could predict adult bone mass. We measured cortical bone mineral content (BMC [g]), bone mineral density (BMD [g/cm2]), and bone width (cm) in the distal forearm by single photon absorptiometry in 120 boys and 94 girls with a mean age of 10 years (range 3–17) and mean 28 years (range 25–29) later. We calculated individual and age-specific bone mass Z scores, using the control cohort included at baseline as reference, and evaluated correlations between the two measurements with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Individual Z scores were also stratified in quartiles to register movements between quartiles from growth to adulthood. BMD Z scores in childhood and adulthood correlated in both boys (r = 0.35, p < 0.0001) and girls (r = 0.50, p < 0.0001) and in both children ≥10 years at baseline (boys r = 0.43 and girls r = 0.58, both p < 0.0001) and children <10 years at baseline (boys r = 0.26 and girls r = 0.40, both p < 0.05). Of the children in the lowest quartile of BMD, 58 % had left the lowest quartile in adulthood. A pediatric bone scan with a value in the lowest quartile had a sensitivity of 48 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 27–69 %) and a specificity of 76 % (95 % CI 66–84 %) to identify individuals who would remain in the lowest quartile also in adulthood. Childhood forearm BMD explained 12 % of the variance in adult BMD in men and 25 % in women. A pediatric distal forearm BMD scan has poor ability to predict adult bone mass.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B et al (2000) Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int 11(12):985–1009

Ahlborg HG, Johnell O, Turner CH, Rannevik G, Karlsson MK (2003) Bone loss and bone size after menopause. N Engl J Med 349(4):327–334

Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC Jr (1990) The contribution of bone loss to postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 1(1):30–34

Kelly PJ, Morrison NA, Sambrook PN, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA (1995) Genetic influences on bone turnover, bone density and fracture. Eur J Endocrinol 133(3):265–271

Matkovic V, Kostial K, Simonovic I, Buzina R, Brodarec A, Nordin BE (1979) Bone status and fracture rates in two regions of Yugoslavia. Am J Clin Nutr 32(3):540–549

Alwis G, Linden C, Stenevi-Lundgren S, Ahlborg HG, Dencker M, Besjakov J, Gardsell P, Karlsson MK (2006) A school-curriculum-based exercise intervention program for two years in pre-pubertal girls does not influence hip structure. J Bone Miner Res 21:829–835

Heinonen A, Oja P, Kannus P et al (1995) Bone mineral density in female athletes representing sports with different loading characteristics of the skeleton. Bone 17(3):197–203

Karlsson MK, Linden C, Karlsson C, Johnell O, Obrant K, Seeman E (2000) Exercise during growth and bone mineral density and fractures in old age. Lancet 355(9202):469–470

Karlsson MK, Weigall SJ, Duan Y, Seeman E (2000) Bone size and volumetric density in women with anorexia nervosa receiving estrogen replacement therapy and in women recovered from anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85(9):3177–3182

Seeman E, Karlsson MK, Duan Y (2000) On exposure to anorexia nervosa, the temporal variation in axial and appendicular skeletal development predisposes to site-specific deficits in bone size and density: a cross-sectional study. J Bone Miner Res 15(11):2259–2265

Ferrari SL, Chevalley T, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R (2006) Childhood fractures are associated with decreased bone mass gain during puberty: an early marker of persistent bone fragility? J Bone Miner Res 21(4):501–507

Chevalley T, Bonjour JP, van Rietbergen B, Ferrari S, Rizzoli R (2011) Fractures during childhood and adolescence in healthy boys: relation with bone mass, microstructure, and strength. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(10):3134–3142

Jones IE, Taylor RW, Williams SM, Manning PJ, Goulding A (2002) Four-year gain in bone mineral in girls with and without past forearm fractures: a DXA study. J Bone Miner Res 17(6):1065–1072

Foley S, Quinn S, Jones G (2009) Tracking of bone mass from childhood to adolescence and factors that predict deviation from tracking. Bone 44(5):752–757

Sundberg M, Gardsell P, Johnell O, Ornstein E, Karlsson MK, Sernbo I (2003) Pubertal bone growth in the femoral neck is predominantly characterized by increased bone size and not by increased bone density—a 4-year longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int 14(7):548–558

Landin L, Nilsson BE (1983) Bone mineral content in children with fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 178:292–296

Helin I, Landin LA, Nilsson BE (1985) Bone mineral content in preterm infants at age 4 to 16. Acta Paediatr Scand 74(2):264–267

Landin L, Nilsson BE (1981) Forearm bone mineral content in children. Normative data. Acta Paediatr Scand 70(6):919–923

Magarey AM, Boulton TJ, Chatterton BE, Schultz C, Nordin BE, Cockington RA (1999) Bone growth from 11 to 17 years: relationship to growth, gender and changes with pubertal status including timing of menarche. Acta Paediatr 88(2):139–146

Jones IE, Williams SM, Dow N, Goulding A (2002) How many children remain fracture-free during growth? A longitudinal study of children and adolescents participating in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Osteoporos Int 13(12):990–995

Goulding A, Grant AM, Williams SM (2007) Characteristics of children experiencing incident fractures: an 8-year longitudinal DXA study of 142 New Zealand girls. Bone 40(6, Suppl 1):S47

Kalkwarf HJ, Gilsanz V, Lappe JM et al (2010) Tracking of bone mass and density during childhood and adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(4):1690–1698

Budek AZ, Mark T, Michaelsen KF, Molgaard C (2010) Tracking of size-adjusted bone mineral content and bone area in boys and girls from 10 to 17 years of age. Osteoporos Int 21(1):179–182

Fujita Y, Iki M, Ikeda Y et al (2011) Tracking of appendicular bone mineral density for 6 years including the pubertal growth spurt: Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis Kids Cohort Study. J Bone Miner Metab 29(2):208–216

Marshall WA, Tanner JM (1970) Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child 45(239):13–23

Bailey DA, McKay HA, Mirwald RL, Crocker PR, Faulkner RA (1999) A six-year longitudinal study of the relationship of physical activity to bone mineral accrual in growing children: the University of Saskatchewan Bone Mineral Accrual Study. J Bone Miner Res 14(10):1672–1679

Boot AM, de Ridder MA, van der Sluis IM, van Slobbe I, Krenning EP, Keizer-Schrama SM (2010) Peak bone mineral density, lean body mass and fractures. Bone 46(2):336–341

Arabi A, Baddoura R, Awada H et al (2007) Discriminative ability of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry site selection in identifying patients with osteoporotic fractures. Bone 40(4):1060–1065

Hovelius B (2002) Treatment with oestrogen. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care, Stockholm

Ahlborg HG, Johnell O, Nilsson BE, Jeppsson S, Rannevik G, Karlsson MK (2001) Bone loss in relation to menopause: a prospective study during 16 years. Bone 28(3):327–331

Acknowledgments

Financial support was received from the Skåne University Hospital and the Österlund, Pahlsson, and Kock Foundations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Bjorn E. Rosengren reports Grants from Skåne University Hospital, Österlund Foundation, and Kocks Foundation, outside the submitted work. Christian Buttazzoni, Magnus Tveit, Lennard Landin, Jan-Åke Nilsson, and Magnus K. Karlsson have nothing to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buttazzoni, C., Rosengren, B.E., Tveit, M. et al. A Pediatric Bone Mass Scan Has Poor Ability to Predict Adult Bone Mass: A 28-Year Prospective Study in 214 Children. Calcif Tissue Int 94, 232–239 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-013-9802-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-013-9802-y