Abstract

Purpose

Ventricular–arterial (V–A) decoupling decreases myocardial efficiency and is exacerbated by tachycardia that increases static arterial elastance (Ea). We thus investigated the effects of heart rate (HR) reduction on Ea in septic shock patients using the beta-blocker esmolol. We hypothesized that esmolol improves Ea by positively affecting the tone of arterial vessels and their responsiveness to HR-related changes in stroke volume (SV).

Methods

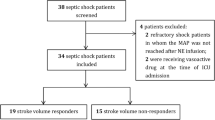

After at least 24 h of hemodynamic optimization, 45 septic shock patients, with an HR ≥95 bpm and requiring norepinephrine to maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65 mmHg, received a titrated esmolol infusion to maintain HR between 80 and 94 bpm. Ea was calculated as MAP/SV. All measurements, including data from right heart catheterization, echocardiography, arterial waveform analysis, and norepinephrine requirements, were obtained at baseline and at 4 h after commencing esmolol.

Results

Esmolol reduced HR in all patients and this was associated with a decrease in Ea (2.19 ± 0.77 vs. 1.72 ± 0.52 mmHg l−1), arterial dP/dt max (1.08 ± 0.32 vs. 0.89 ± 0.29 mmHg ms−1), and a parallel increase in SV (48 ± 14 vs. 59 ± 18 ml), all p < 0.05. Cardiac output and ejection fraction remained unchanged, whereas norepinephrine requirements were reduced (0.7 ± 0.7 to 0.58 ± 0.5 µg kg−1 min−1, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

HR reduction with esmolol effectively improved Ea while allowing adequate systemic perfusion in patients with severe septic shock who remained tachycardic despite standard volume resuscitation. As Ea is a major determinant of V–A coupling, its reduction may contribute to improving cardiovascular efficiency in septic shock.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al (2013) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Intensive Care Med 39:165–228

Cecconi M, De Backer D, Antonelli M et al (2014) Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 40:1795–1815

Angus DC, Barnato AE, Bell D et al (2015) A systematic review and meta-analysis of early goal-directed therapy for septic shock: the ARISE, ProCESS and ProMISe Investigators. Intensive Care Med 41:1549–1560

Guarracino F, Ferro B, Morelli A, Bertini P, Baldassarri R, Pinsky MR (2014) Ventriculoarterial decoupling in human septic shock. Crit Care 18:R80

Guarracino F, Baldassarri R, Pinsky MR (2013) Ventriculo-arterial decoupling in acutely altered hemodynamic states. Crit Care 17:213

Vieillard-Baron A, Caille V, Charron C, Belliard G, Page B, Jardin F (2008) Actual incidence of global left ventricular hypokinesia in adult septic shock. Crit Care Med 36:1701–1706

Ohte N, Cheng CP, Little WC (2003) Tachycardia exacerbates abnormal left ventricular–arterial coupling in heart failure. Heart Vessels 18:136–141

Prabhu SD (2007) Altered left ventricular–arterial coupling precedes pump dysfunction in early heart failure. Heart Vessels 22:170–177

Magder SA (2012) The ups and downs of heart rate. Crit Care Med 40:239–245

Azimi G, Vincent JL (1986) Ultimate survival from septic shock. Resuscitation 14:245–253

Parker MM, Shelhamer JH, Natanson C, Alling DW, Parrillo JE (1987) Serial cardiovascular variables in survivors and nonsurvivors of human septic shock: heart rate as an early predictor of prognosis. Crit Care Med 15:923–929

Morelli A, Ertmer C, Westphal M et al (2013) Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310:1683–1691

Vellinga NA, Boerma EC, Koopmans M et al (2015) International study on microcirculatory shock occurrence in acutely ill patients. Crit Care Med 43:48–56

Leibovici L, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M et al (2007) Relative tachycardia in patients with sepsis: an independent risk factor for mortality. QJM 100:629–634

Dekleva M, Lazic JS, Soldatovic I et al (2015) Improvement of ventricular–arterial coupling in elderly patients with heart failure after beta blocker therapy: results from the CIBIS-ELD trial. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 29:287–294

Razzolini R, Tarantini G, Boffa GM, Orlando S, Iliceto S (2004) Effects of carvedilol on ventriculo-arterial coupling in patients with heart failure. Ital Heart J 5:517–522

Romano SM, Pistolesi M (2002) Assessment of cardiac output from systemic arterial pressure in humans. Crit Care Med 30:1834–1841

Scolletta S, Bodson L, Donadello K, Taccone FS, Devigili A, Vincent JL, De Backer D (2013) Assessment of left ventricular function by pulse wave analysis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 39:1025–1033

Lewis T (1906) The factors influencing the prominence of the dicrotic wave. J Physiol 34:414–429

Smith D, Craige E (1986) Mechanism of the dicrotic pulse. Br Heart J 56:531–534

Fincke R, Hochman JS, Lowe AM et al (2004) Cardiac power is the strongest hemodynamic correlate of mortality in cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 44:340–348

Sunagawa K, Maughan WL, Burkhoff D, Sagawa K (1983) Left ventricular interaction with arterial load studied in the isolated canine ventricle. Am J Physiol 245:H733–H788

Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, Townsend SR, Schorr CA, Beale R, Osborn T, Lemeshow S, Chiche JD, Artigas A, Dellinger RP (2014) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Intensive Care Med 40:1623–1633

Rhodes A, Phillips G, Beale R et al (2015) The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundles and outcome: results from the International Multicentre Prevalence Study on Sepsis (the IMPreSS study). Intensive Care Med 41:1620–1628

Freeman GL, Little WC, O’Rourke RA (1987) Influence of heart rate on the left ventricular performance in conscious dogs. Circ Res 61:455–464

Rudiger A, Singer M (2007) Mechanisms of sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction. Crit Care Med 35:1599–1608

Sanfilippo F, Santonocito C, Morelli A, Foex P (2015) Beta-blocker use in severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 31:1817–1825

Pemberton P, Veenith T, Snelson C, Whitehouse T (2015) Is it time to beta block the septic patient? Biomed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2015/424308

Asfar P, Meziani F, Hamel JF et al (2014) High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med 370:1583–1593

Sanfilippo F, Corredor C, Fletcher N, Landesberg G, Benedetto U, Foex P, Cecconi M (2015) Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in septic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 41:1004–1013

Repessé X, Charron C, Vieillard-Baron A (2013) Evaluation of left ventricular systolic function revisited in septic shock. Crit Care 17(4):164

Kimmoun A, Louis H, Kattani NA et al (2015) β1-adrenergic inhibition improves cardiac and vascular function in experimental septic shock. Crit Care Med 43:e332–e340

Ogura Y, Jesmin S, Yamaguchi N et al (2014) Potential amelioration of upregulated renal HIF-1alpha-endothelin-1 system by landiolol hydrochloride in a rat model of endotoxemia. Life Sci 118:347–356

Seki Y, Jesmin S, Shimojo N et al (2014) Significant reversal of cardiac upregulated endothelin-1 system in a rat model of sepsis by landiolol hydrochloride. Life Sci 118:357–363

Bergel DH (1961) The dynamic elastic properties of the arterial wall. J Physiol 156:458–469

Giannattasio C, Vincenti A, Failla M et al (2003) Effects of heart rate changes on arterial distensibility in humans. Hypertension 42:253–256

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Andrea Morelli received honoraria for speaking at Baxter symposia. Mervyn Singer served as a consultant and received honoraria for speaking and chairing symposia for Baxter. Salvatore Mario Romano has a patent “Method and apparatus for measuring cardiac flow output” (USA Patent Number 6758822). No other disclosures were reported.

Additional information

Take-home message: Despite achieving recommended hemodynamic targets, ventricular-arterial decoupling may persist in patients with septic shock and it can deteriorate progressively during the course of the disease. Such patients may potentially benefit from therapies aimed at normalizing V–A coupling. Among them, HR reduction with esmolol could effectively improve Ea while allowing adequate systemic perfusion in septic shock patients remaining tachycardic despite standard resuscitation. As Ea is a major determinant of V–A coupling, its reduction may contribute to improving cardiovascular efficiency in septic shock.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morelli, A., Singer, M., Ranieri, V.M. et al. Heart rate reduction with esmolol is associated with improved arterial elastance in patients with septic shock: a prospective observational study. Intensive Care Med 42, 1528–1534 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4351-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4351-2