Abstract

Hypothermia can reduce neurodevelopmental disabilities in asphyxiated newborn infants. However, the optimal cooling temperature for neuroprotection is not well defined. We studied the effects of transient piglet brain hypoxic ischemia (HI) on transcriptional activity of eight genes and if mRNA level alterations could be counteracted by whole body cooling to 35, 33.5 or 30 °C. BDNF mRNA was globally upregulated by the insult, and none of the cooling temperatures counteracted this change. In contrast, MANF mRNA was downregulated, and these changes were modestly counteracted in different brain regions by hypothermic treatment at 33.5 °C, while 30 °C aggravated the MANF mRNA loss. MAP2 mRNA was markedly downregulated in all brain regions except striatum, and cooling to 33.5 °C modestly counteract this downregulation in the cortex cerebri. There was a tendency for GFAP mRNA levels in core, but not mantle regions to be downregulated and for these changes to be modestly counteracted by cooling to 33.5 or 35 °C. Cooling to 30 °C caused global GFAP mRNA decrease. HSP70 mRNA tended to become upregulated by HI and to be more pronounced in cortex and CA1 of hippocampus during cooling to 33.5 °C. We conclude that HI causes alterations of mRNA levels of many genes in superficial and deep piglet brain areas. Some of these changes may be beneficial, others detrimental, and lowering body temperature partly counteracts some, but not all changes. There may be general differences between core and mantle regions, as well as between the different cooling temperatures for protection. Comparing the three studied temperatures, cooling to 33.5 °C, appears to provide the best cooling temperature compromise.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Azzopardi D, Brocklehurst P, Edwards D, Halliday H, Levene M, Thoresen M, et al. The TOBY Study. Whole body hypothermia for the treatment of perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:17.

Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, Dyet L, Halliday HL, Juszczak E, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1349–58.

Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, Tyson JE, McDonald SA, Donovan EF, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1574–84.

Edwards AD, Brocklehurst P, Gunn AJ, Halliday H, Juszczak E, Levene M, et al. Neurological outcomes at 18 months of age after moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy: synthesis and meta-analysis of trial data. BMJ. 2010;340:c363.

Jacobs S, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi W, Inder T, Davis P. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(4):CD003311.

Jacobs SE, Morley CJ, Inder TE, Stewart MJ, Smith KR, McNamara PJ, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for term and near-term newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:692–700.

Johnston MV, Fatemi A, Wilson MA, Northington F. Treatment advances in neonatal neuroprotection and neurointensive care. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:372–82.

Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:329–38.

Perlman M, Shah PS. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: challenges in outcome and prediction. J Pediatr. 2011;158:e51–4.

Roka A, Azzopardi D. Therapeutic hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:361–7.

Hobbs C, Thoresen M, Tucker A, Aquilina K, Chakkarapani E, Dingley J. Xenon and hypothermia combine additively, offering long-term functional and histopathologic neuroprotection after neonatal hypoxia/ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39:1307–13.

Burnard ED, Cross KW. Rectal temperature in the newborn after birth asphyxia. Br Med J. 1958;2:1197–9.

Clarke L, Heasman L, Firth K, Symonds ME. Influence of route of delivery and ambient temperature on thermoregulation in newborn lambs. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1931–9.

Okken AKJ. Thermoregulation of sick and low birth weight neonates. LŸbeck: Springer; 1995.

Pierrat V, Haouari N, Liska A, Thomas D, Subtil D, Truffert P. Prevalence, causes, and outcome at 2 years of age of newborn encephalopathy: population based study. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:F257–61.

Christensson K, Siles C, Cabrera T, Belaustequi A, de la Fuente P, Lagercrantz H, et al. Lower body temperatures in infants delivered by caesarean section than in vaginally delivered infants. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82:128–31.

Iwata S, Iwata O, Olson L, Kapetanakis A, Kato T, Evans S, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia can be induced and maintained using either commercial water bottles or a “phase changing material” mattress in a newborn piglet model. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:387–91.

Agnew DM, Koehler RC, Guerguerian AM, Shaffner DH, Traystman RJ, Martin LJ, et al. Hypothermia for 24 hours after asphyxic cardiac arrest in piglets provides striatal neuroprotection that is sustained 10 days after rewarming. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:253–62.

Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, Ballard R, Edwards AD, Ferriero DM, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:663–70.

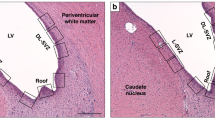

Iwata S, Iwata O, Thornton JS, Shanmugalingam S, Bainbridge A, Peebles D, et al. Superficial brain is cooler in small piglets: neonatal hypothermia implications. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:578–85.

Liu X, Chakkarapani E, Hoque N, Thoresen M. Environmental cooling of the newborn pig brain during whole-body cooling. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:29–35.

Iwata O, Thornton JS, Sellwood MW, Iwata S, Sakata Y, Noone MA, et al. Depth of delayed cooling alters neuroprotection pattern after hypoxia-ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:75–87.

Thoresen M, Penrice J, Lorek A, Cady E, Wylezinska M, Kirkbride V. Mild hypothermia following severe transient hypoxia-ischaemia ameliorates delayed cerebral energy failure in the newborn piglet. Pediatr Res. 1995;37:667–70.

Faulkner S, Bainbridge A, Kato T, Chandrasekaran M, Kapetanakis AB, Hristova M, et al. Xenon augmented hypothermia reduces early lactate/N-acetylaspartate and cell death in perinatal asphyxia. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:133–50.

Ross JM, Oberg J, Brene S, Coppotelli G, Terzioglu M, Pernold K, et al. High brain lactate is a hallmark of aging and caused by a shift in the lactate dehydrogenase A/B ratio. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20087–92.

Lorek A, Takei Y, Cady EB, Wyatt JS, Penrice J, Edwards AD, et al. Delayed (“secondary”) cerebral energy failure after acute hypoxia-ischemia in the newborn piglet: continuous 48-hour studies by phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Pediatr Res. 1994;36:699–706.

Felix B, Leger ME, Albe-Fessard D, Marcilloux JC, Rampin O, Laplace JP. Stereotaxic atlas of the pig brain. Brain Res Bull. 1999;49:1–137.

Dagerlind A, Friberg K, Bean AJ, Hokfelt T. Sensitive mRNA detection using unfixed tissue: combined radioactive and non-radioactive in situ hybridization histochemistry. Histochemistry. 1992;98:39–49.

Karlen A, Karlsson TE, Mattsson A, Lundstromer K, Codeluppi S, Pham TM, et al. Nogo receptor 1 regulates formation of lasting memories. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20476–81.

Marlow N, Budge H. Prevalence, causes, and outcome at 2 years of age of newborn encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:F193–4.

Schulzke SM, Rao S, Patole SK. A systematic review of cooling for neuroprotection in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy—are we there yet? BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:30.

Gunn AJ, Gunn TR, de Haan HH, Williams CE, Gluckman PD. Dramatic neuronal rescue with prolonged selective head cooling after ischemia in fetal lambs. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:248–56.

Sirimanne ES, Blumberg RM, Bossano D, Gunning M, Edwards AD, Gluckman PD, et al. The effect of prolonged modification of cerebral temperature on outcome after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in the infant rat. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:591–7.

Taylor DL, Mehmet H, Cady EB, Edwards AD. Improved neuroprotection with hypothermia delayed by 6 hours following cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in the 14-day-old rat. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:13–9.

Colbourne F, Corbett D. Delayed postischemic hypothermia: a six month survival study using behavioral and histological assessments of neuroprotection. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7250–60.

Wagner BP, Nedelcu J, Martin E. Delayed postischemic hypothermia improves long-term behavioral outcome after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rats. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:354–60.

Laptook AR, Corbett RJ, Burns DK, Sterett R. A limited interval of delayed modest hypothermia for ischemic brain resuscitation is not beneficial in neonatal swine. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:383–9.

Olson L. On neonatal asphyxia: clinical and animal studies including development of a simple, safe method for therapeutic hypothermia with global applicability. Thesis. Stockholm: Dep of Women’s and Children’s Health, Karolinska Institutet; 2011.

Faulkner S, Bainbridge A, Kelen D, Thayyil S, Chandrasekaran M, Kato T, et al. Whole body cooling to 35, 33 and 30 °C in a piglet model of hypoxic ischemic brain injury: which is the optimal temperature? In: Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, CA, USA, 2010. p. 1.

Lewin GR, Barde YA. Physiology of the neurotrophins. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:289–317.

Wetmore C, Ernfors P, Persson H, Olson L. Localization of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA to neurons in the brain by in situ hybridization. Exp Neurol. 1990;109:141–52.

Isackson PJ, Huntsman MM, Murray KD, Gall CM. BDNF mRNA expression is increased in adult rat forebrain after limbic seizures: temporal patterns of induction distinct from NGF. Neuron. 1991;6:937–48.

Schmidt-Kastner R, Humpel C, Wetmore C, Olson L. Cellular hybridization for BDNF, trkB, and NGF mRNAs and BDNF-immunoreactivity in rat forebrain after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Exp Brain Res. 1996;107:331–47.

Wetmore C, Olson L, Bean AJ. Regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and release from hippocampal neurons is mediated by non-NMDA type glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1688–700.

Han BH, Holtzman DM. BDNF protects the neonatal brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury in vivo via the ERK pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20(15):5775–81.

Almli CR, Levy TJ, Han BH, Shah AR, Gidday JM, Holtzman DM, et al. BDNF protects against spatial memory deficits following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2000;166(1):99–114.

Lindholm P, Peranen J, Andressoo JO, Kalkkinen N, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O, et al. MANF is widely expressed in mammalian tissues and differently regulated after ischemic and epileptic insults in rodent brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;39(3):356–71.

Giffard RG, Han RQ, Emery JF, Duan M, Pittet JF. Regulation of apoptotic and inflammatory cell signaling in cerebral ischemia: the complex roles of heat shock protein 70. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:339–48.

Xiao-Yan X, Yi-Xin X. Effects of graded hypothermia on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in the neonatal rat. Chin Med Sci J. 2011;26:49–53.

Lingwood BE, Healy GN, Sullivan SM, Pow DV, Colditz PB. MAP2 provides reliable early assessment of neural injury in the newborn piglet model of birth asphyxia. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;171:140–6.

Josephson A, Trifunovski A, Scheele C, Widenfalk J, Wahlestedt C, Brene S, et al. Activity-induced and developmental downregulation of the Nogo receptor. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:333–42.

Kerenyi A, Kelen D, Faulkner SD, Bainbridge A, Chandrasekaran M, Cady EB, et al. Systemic effects of whole-body cooling to 35 °C, 33.5 °C, and 30 °C in a piglet model of perinatal asphyxia: implications for therapeutic hypothermia. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(5):573–82.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eva Lindqvist and Karin Pernold for the excellent technical support. This study is supported by the Märtha Lundqvist stiftelse (LO), The Swedish Research Council (HL, LO, DG), Stiftelsen Barncentrum (LO), The British MRC (NR), Karolinska Institutet, The Karolinska Distinguished Professor Award (LO), and Swedish Brain Power (LO, DG). The preparation of piglets until sacrifice and administration of hypothermia was undertaken at UCLH/UCL, with funding from the United Kingdom Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centres (NR). In situ hybridization for lactate dehydrogenases is supported by the National Institute on Aging, NIH (AG04418), and in situ hybridization for plasticity genes (BDNF and NgR) is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH (LO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olson, L., Faulkner, S., Lundströmer, K. et al. Comparison of Three Hypothermic Target Temperatures for the Treatment of Hypoxic Ischemia: mRNA Level Responses of Eight Genes in the Piglet Brain. Transl. Stroke Res. 4, 248–257 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-012-0215-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-012-0215-4