Abstract

How do citizens in weak democracies evaluate claims on government assistance made by other ethnic groups? This paper analyzes data from an original survey experiment in the Republic of Georgia to determine the role of ethnic cues in the formation of redistributive preferences. In the experiment, ethnic Georgian subjects are randomly assigned a mock news article with variation on implied ethnic (Georgian, Azeri, or Armenian) identity and type of redistributive demand, and asked to evaluate the demand. The results show modest but consistent evidence of ethnic bias conditional on both types of variation, along with ethnic stereotypes, even while subjects are highly pro-redistribution in general. This study highlights how subtle biases can shape redistributive policy preferences in ways inimical to democracy in multiethnic societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Georgia also has high religious diversity. Shia Islam predominates among Azeris, Armenians belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church, and the western Georgian region of Ajara has a sizeable population of Sunni ethnic Georgians.

Details on sampling can be found in the appendix.

Kitschelt and Wilkinson (2007: 11) argue that club goods can be allocated according to programmatic or clientelistic principles. A policy would be considered programmatic if it were structured to address general needs that happen to correspond with those of the intended beneficiaries (p. 12). Allocations to alleviate environmental and health problems could work according to either logic, and readers of the vignette may interpret the claim either way.

The vignettes were drafted through several revisions in consultation with Georgian and foreign experts. The differing details in the two vignettes were a product of ensuring that each vignette was internally coherent and possessed experimental realism (McDermott 2002: 333).

Correct identifications were made as follows for the three implied groups: Georgian 83.8 %, Armenian 68.0 %, Azeri 71.8 %.

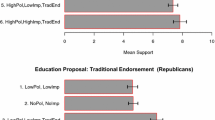

All three variables are scored so that higher numbers indicate greater sympathy or support for the claim.

For the full sample, the differences in means are .08 and .12, respectively.

A multinomial model estimates the effect of a one-unit change in a predictor variable on the log-odds of moving from one level of the dependent variable to the next highest level. I use the proportional odds variant of the model because there are no theoretical reasons to suspect that changes in score should be non-constant. Thus, change in log odds is the same for the transition from any score on the dependent variable to the next highest score

For an overview, see Bratton (2013).

References

Abdelal R, Herrera YM, Johnston AI, McDermott R. Identity as a variable. Perspect Polit. 2006;4(4):695–711.

Alesina A, Reza B, Easterly W. Public goods and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ. 1999;114(4):1243–84.

Baldwin K, Huber JD. Economic versus cultural differences: forms of ethnic diversity and public goods provision. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104(4):644–62.

Barth F, ed. Ethnic groups and boundaries. Universitets Forlaget; 1970.

Bates RH. Ethnic competition and modernization in contemporary Africa. Comp Polit Stud. 1974;6(4):457–84.

Berinsky AJ. The two faces of public opinion. Am J Polit Sci. 1999;43(4):1209–30.

Bonacich E. A theory of middleman minorities. Am Sociol Rev. 1973;38(5):583–94.

Brader T, Valentino NA, Suhay E. What triggers public opposition to immigration? Anxiety, group cues, and immigration threat. Am J Polit Sci. 2008;52(4):959–78.

Bratton M, ed. Voting and democratic citizenship in Africa. Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2013.

Brubaker R. Nationalism refrained: nationhood and the national question in the new Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

Brubaker R. Nationalist politics and everyday ethnicity in a Transylvanian town. Princeton University Press; 2006.

Brubaker R, Loveman M, Stamatov P. Ethnicity as cognition. Theory Soc. 2004;33:31–64.

Chandra K. Why ethnic parties succeed: patronage and ethnic head counts in India. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Cheterian V. Georgia's rose revolution: change or repetition? Tension between state-building and modernization projects. National Pap. 2008;36(4):689–712.

Cohen FS. Proportional versus majoritarian ethnic conflict management in democracies. Comp Polit Stud. 1997;30(5):607–30.

Conroy-Krutz J. Information and ethnic politics in Africa. Br J Polit Sci. 2013;43(2):1–29.

Cook LJ. Postcommunist welfare states: reform politics in Russia and Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press; 2007.

Corneo G, Grüner HP. Individual preferences for political redistribution. J Public Econ. 2002;83(1):83–107.

Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56(1):5–18.

Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychol Sci. 2000;11(4):315–9.

Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Aversive racism. In Olson JM and Zanna MP eds., Advances in experimental social psychology, volume 36. Academic Press; 2004.

Dunning T, Harrison L. Cross-cutting cleavages and ethnic voting: an experimental study of cousinage in Mali. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104(1):21–39.

Easterly W, Levine R. Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ. 1997;112(4):1203–50.

Eastwood W. Processions in the street: Georgian orthodox privilege and religious minorities’ response to invisibility. Anthropol East Eur Rev. 2010;27(1):20–8.

Eifert B, Miguel E, Posner DN. Political competition and ethnic identification in Africa. Am J Polit Sci. 2010;54(2):494–510.

Elbakidze M. Multi-ethnic society in Georgia: a pre-condition for xenophobia or an arena for cultural dialogue? Anthropol East Eur Rev. 2008;26(1):37–50.

Fearon JD. Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. J Econ Growth. 2003;8(2):195–222.

Fearon JD, Laitin DD. Violence and the social construction of ethnic identity. Int Organ. 2000;54(4):845–77.

Flintoff C. Anti-gay riot in Tblisi tests balance between church, state, NPR, July 30, 2013; http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2013/07/30/204511294/GEORGIA-CHURCH-ANTI-GAY-RIOT.

Freedman DA. Statistical models for causation what inferential leverage do they provide? Eval Rev. 2006;30(6):691–713.

George JA. The dangers of reform: state building and national minorities in Georgia. Cent Asian Surv. 2009;28(2):135–54.

Grzymala-Busse A. Beyond clientelism incumbent state capture and state formation. Comp Polit Stud. 2008;41(4–5):638–73.

Habyarimana J, Humphreys M, Posner DN, Weinstein JM. Why does ethnic diversity undermine public goods provision? Am Polit Sci Rev. 2007;101(4):709–25.

Hagendoorn L, Linssen H, Tumanov S, editors. Intergroup relations in states of the former Soviet Union: the perception of Russians. Philadelphia: Psychology Press; 2001.

Hale HE. Explaining ethnicity. Comp Polit Stud. 2004;37(4):458–85.

Hicken A. Clientelism. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2011;14:289–310.

Horowitz DL. Ethnic groups in conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985.

Ichino N, Nathan NL. Crossing the line: local ethnic geography and voting in Ghana. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2013;107(2):1–18.

Imai K, King G, Lau O. Zelig: everyone's statistical software 2009.

International Crisis Group. Georgia’s Armenian and Azeri minorities. November 22, 2006.

Kasara K. Tax me if you can: ethnic geography, democracy, and the taxation of agriculture in Africa. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2007;101(1):159–72.

Kitschelt H, Wilkinson SI. Citizen-politician linkages: an introduction. In: Kitschelt H, Wilkinson SI, editors. Patrons, clients, and policies: patterns of democratic accountability and political competition. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny R. The quality of government. J Law Econ Org. 1999;15(1):222–79.

Laitin DD. Hegemony and culture: politics and change among the Yoruba. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1986.

Lau RR, Redlawsk DP. Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. Am J Polit Sci. 2001;45(4):951–71.

Lee YJ, Ellenberg JH, Hirtz DG, Nelson KB. Analysis of clinical trials by treatment actually received: is it really an option? Stat Med. 1991;10(10):1595–605.

Lieberman ES, Singh P. Conceptualizing and measuring ethnic politics: an institutional complement to demographic, behavioral, and cognitive approaches. Stud Comp Int Dev. 2012;47(3):255–86.

Lijphart A. Democracy in plural societies: a comparative exploration. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1977.

Lipsmeyer C, Nordstrom Y. East versus west: comparing political attitudes and welfare preferences across European societies. J Eur Pub Policy. 2003;10(3):339–64.

Martin T. The affirmative action empire: national and nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–39. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2001.

McDermott R. Experimental methodology in political science. Polit Anal. 2002;10(4):325–42.

Mendelberg T. Executing Hortons: racial crime in the 1988 presidential campaign. Pub Opin Q. 1997;61:134–57.

Mendelberg T. The race card: campaign strategy, implicit messages, and the norm of equality. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2001.

Miguel E, Gugerty MK. Ethnic diversity, social sanctions, and public goods in Kenya. J Public Econ. 2005;89(11–12):2325–68.

Nobles, M. Shades of citizenship: race and the census in modern politics. Stanford University Press; 2000

Peffley M, Rohrschneider R. Democratization and political tolerance in seventeen countries: a multi-level model of democratic learning. Polit Res Q. 2003;56(3):243–57.

Peffley M, Hurwitz J, Sniderman PM. Racial stereotypes and whites’ political views of blacks in the context of welfare and crime. Am J Polit Sci. 1997;41(1):30–60.

Petersen RD. Understanding ethnic violence: fear, hatred, and resentment in twentieth-century Eastern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Pop-Eleches G. Throwing out the bums: protest voting and unorthodox parties after communism. World Polit. 2010;62:221–60.

Posner DN. The political salience of cultural difference: why Chewas and Tumbukas are allies in Zambia and adversaries in Malawi. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2005a;98:529–45.

Posner DN. Institutions and ethnic politics in Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005b.

Reeves K. Voting hopes or fears? White voters, black candidates, and racial politics in America. Oxford University Press; 1997.

Remmer KL. The political economy of patronage: expenditure patterns in the Argentine provinces, 1983–2003. J Polit. 2007;69(2):363–77.

Riker H. The theory of political coalitions. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1962.

Robinson JA, Verdier T. The political economy of clientelism. Rochester: Social Science Research Network; 2002.

Slezkine Y. The USSR as a communal apartment, or how a socialist state promoted ethnic particularism. Slav Rev. 1994;53(2):414–52.

Sniderman PM, Piazza T, Tetlock PE, Kendrick A. The new racism. Am J Polit Sci. 1991;53(2):423–47.

Sniderman PM, Hagendoorn L, Prior M. Predisposing factors and situational triggers: exclusionary reactions to immigrant minorities. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2004;98(1):35–49.

Suny RG. The making of the Georgian nation. Indiana University Press; 1994.

Tajfel H. Human groups and social categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1981.

Taylor DM, Fathali MM. Theories of intergroup relations: international social psychological perspectives. New York: Freeman; 1994.

Transue JE. Identity salience, identity acceptance, and racial policy attitudes: American national identity as a uniting force. Am J Polit Sci. 2007;51:78–91.

Valentino NA, Hutchings VL, White IK. Cues that matter: how political ads prime racial attitudes during campaigns. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2002;96(1):75–90.

Van de Walle N. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss? The evolution of political clientelism in Africa. In Kitschelt H, Wilkinson SI, eds. Patrons, clients and policies: patterns of democratic accountability and political competition. Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Wantchekon L. Clientelism and voting behavior: evidence from a field experiment in Benin. World Polit. 2003;55(3):399–422.

Weghorst KR, Lindberg SI. What drives the swing voter in Africa? Am J Polit Sci. 2013;57(3):717–34.

Wheatley J. Managing ethnic diversity in Georgia: one step forward, two steps back. Cent Asian Surv. 2009;28(2):119–34.

World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gg.htmll; 2014.

Zürcher C. The post-Soviet wars: rebellion, ethnic conflict, and nationhood in the Caucasus. New York: New York University Press; 2007.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Koba Turmanidze, Tina Zurabishvili, and Tiko Ambroladze at the Caucasus Research Resource Center in Tbilisi for consultation and implementation of the survey. Julie George, Tim Blauvelt, Hans Gutbrod, Tom Trier, Charles King, Yoshiko Herrera, Elise Giuliano, Resat Kasaba, Sara Curran, Sunila Kale, Anand Yang, Joel Migdal, Jesse Driscoll, and David Siroky provided helpful comments on the proposal and working papers. Patrick Underwood provided valuable research assistance. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the International Studies Association, American Political Science Association, and Arizona State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Survey Methodology

Appendix: Survey Methodology

The survey was conducted by the Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) according to a multistage cluster sampling design. The country was divided into four rural and four urban strata plus the capital. Within each stratum, electoral precincts, which functioned as primary sampling units (PSUs), were selected in proportion to the population of registered voters. Households were randomly sampled from a sample frame of households in each PSU and a Kish Grid was used to select the respondent.

The vignettes and questions were translated into local languages (Georgian, Russian, Armenian, and Azeri) and back-translated for validity. They were tested in a pilot survey in September 2012, revised, and fielded as part of the Caucasus Barometer (CB) project in November. Interviewers were sociologists trained by CRRC who spoke local languages. The response rate was 75 %.

Interviewers adhered to the following randomization protocol:

-

1.

Vignettes will be numbered 1 to 6, with the number visible to the interviewer but not to the respondent. Interviewers will select one card, beginning with #1 for the first interview and note on the questionnaire which card they will be using when filling out basic information immediately prior to commencing the interview.

-

2.

When it is time for this block of questions, interviewers will read and show the card to the respondent. The respondent may look at the card the whole time while answering the questions. The interviewer is not allowed to help or reveal any information about the vignette.

-

3.

Interviewers will proceed through the cards in order, until they have gone through all six versions (to six respondents). Then, with the seventh interview, they begin the cycle again, and continue in this manner until they fulfill their quota of interviews.

-

4.

If a respondent drops out and is not included in the CB, then the card intended for that respondent shall be used on the next respondent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Radnitz, S. Ethnic Cues and Redistributive Preferences in Post-Soviet Georgia. St Comp Int Dev 52, 278–300 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-015-9204-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-015-9204-4