Abstract

Criticisms of the system by which the American political parties select their candidates focus on issues of representativeness—how choices are dominated by relatively small numbers of ideologically extreme primary voters, or how residents of small states voting early in the process have disproportionate influence. This paper adds a different concern, albeit one that still addresses representativeness. How well do primary and caucus voters represent their own values and interests with their vote choices? Lau and Redlawsk’s notion of “correct voting” is applied to the 2008 U.S. nominating contests. Four reasons to expect levels of correct voting to be lower in caucus and primary elections than in general election campaigns are discussed. Results suggest that voters in U.S. nominating contests do much worse than voters in general election campaigns, often barely doing better than chance in selecting the candidate who best represents their own values and priorities. Discussion focuses on institutional reforms that should improve citizens’ ability to make correct voting choices in caucuses and primaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This 2008 figure is not the “final” estimate, as the ANES has still not released any data with the open-ended questions coded. This includes answers to several of the political knowledge questions, which are used to identify experts whose mean responses provide “objective” estimates of where the candidates actually stand on the issues, how well the different traits describe them, and how good of a job President Bush did as president. The 2008 estimates will probably change slightly once these data have been coded and released.

Lau et al. (2008) reported that, all else equal, the most knowledgeable voters were 20% more likely to vote correctly, compared to voters with very low political knowledge. Similarly, Lau and Redlawsk (2006) report from experimental data that a large number (15) of accurate memories about mock presidential election candidates increases the probability of a correct vote from .55 to .82. In practice knowledge will typically also be correlated with stronger and less likely to change preferences, which should also lead to higher levels of correct voting, although these influences are conceptually distinct from knowledge per se.

See Jackman and Vavreck 2011, for a more complete description of this sample and the sampling procedures.

The syntax commands used to operationalize correct voting in the 2008 CCAP data, along with replication data for the analyses reported below, are available from the author web page http://fas-polisci.rutgers.edu/lau.

Thompson withdrew after the South Carolina Republican primary on January 19th. Edwards and Giuliani withdrew after the Florida primary on January 29th. Romney withdrew after the “Super Tuesday” contests on February 5th. Huckabee withdrew and McCain claimed the Republican nomination after the four primaries on March 4th. In contrast, Clinton continued fighting through the last primaries on June 3rd.

All analyses were repeated with the weighted sums measure, and with electability counted only once. The results vary little from those reported in Table 1.

There was some evidence that cosmopolitanism (Jackman and Vavreck 2011) played the same role for Republicans that racial prejudice played for Democrats, decreasing the probability that Republicans who otherwise should have preferred Huckabee, from voting for him. But this finding was not consistent across all of the different variants of the dependent variable, and I therefore dropped it from my reported analysis.

Time is operationalized as the number of days in the year 2008. It starts at 3, when the Iowa caucuses were held on January 3rd, and ends at 155, when the Montana and South Dakota primaries were held on June 3rd.

See also Carey and Hix (2011). Interestingly, the rules adopted by the Republican party for the 2012 election make proportional allocation of delegates a punishment for any state (like Florida and Michigan in 2008) that jumps out of line and holds its nominating contest too early.

Including the recent finding that turnout in primary and caucus elections spills over into a higher probability of voting in the subsequent general election campaign (Jones-Correa and Walker 2011), which I would like to encourage. Gerken and Rand (2010), building off of deliberative polls, offer an interesting but more radical idea that might accomplish my goal, a sort of “citizen assembly” that would be randomly chosen and charged with learning about and “vetting” potential party nominees.

I do favor some sort of public financing of election campaigns that would help equal out imbalances in campaign finances, however.

Party identification and retrospective evaluations of the incumbent’s job performance, which are important parts of the calculation of candidate utility scores in a general election campaign, are irrelevant in a primary election because those considerations apply equally to all candidates within a given party (when no incumbent is seeking re-election).

All analyses were repeated with a directional algorithm (Rabinowitz and MacDonald 1989), which produces essentially identical results as those reported herein.

The surveys also asked respondents which candidate they thought was the most viable—that is, which candidate they thought was most likely to win their party’s nomination. Despite Abramson et al.’s (1992) use of such viability beliefs in their study of “sophisticated” voting in the 1988 presidential primaries, and their claim (in fn 1) that it does not matter much empirically whether they use viability or electability beliefs in their analysis, I see obvious reasons why voters should consider electability in their vote choices, but can think of no logic for similarly including viability beliefs into a determination of correct voting, after accounting for electability concerns. Viability clearly does matter to the big donors who are providing the money to the different candidates who are seeking the nomination, and to the campaign consultants who will continue to be employed during the general election campaign if the pick a winner in the primaries. But I cannot see any rationale for why the average citizen would be any “better off” if they voted for the winning candidate in a primary election. Abramowitz (1989) might disagree.

References

Abramowitz, A. I. (1989). Viability, electability, and candidate choice in a presidential primary election: A test of competing models. Journal of Politics, 51(4), 977–992.

Abramson, P. R., Aldrich, J. H., Paolino, P., & Rohde, D. (1992). “Sophisticated” voting in the 1988 presidential primaries. American Political Science Review, 86(1), 55–69.

Aldrich, J. H. (1980). Before the convention: Strategies and choices in presidential nomination campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bartels, L. M. (1988). Presidential primaries and the dynamics of public choice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bartels, L. M. (1996). Uninformed votes: Information effects in presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 194–230.

Carey, J. M., & Hix, S. (2011). The electoral sweet spot: Low-magnitude proportional electoral systems. American Journal of Political Science, 55(2), 383–397.

Cohen, M., Karol, D., Noel, H., & Zaller, J. (2008). The party decides: Presidential nominations before and after reform. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Converse, P. E. (1964). Attitudes and non-attitudes: Continuation of a dialogue. In E. Tufte (Ed.), The quantitative analysis of social problems. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Converse, P. E. (1975). Public opinion and voting behavior. In F. Greenstein & N. Polsby (Eds.), Handbook of political science (Vol. 4, pp. 75–170). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Crotty, W. J., & Jackson, J. S. (1985). Presidential primaries and nominations. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Dawson, M. C. (1994). Behind the mule: Race and class in African-American politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Delli Carpini, M., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Dwyer, C. E. (2011). Packed primaries and empty caucuses: Voter turnout in presidential nomination contests. Paper presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, 31 Mar–3 Apr 2011.

Feldman, S., & Huddy, L. (2005). Racial resentment and White opposition to race-conscious programs: Principles or prejudice? American Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 168–183.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Geer, J. G. (1988). Assessing the representativeness of electorates in presidential primaries. American Journal of Political Science, 32(4), 929–945.

Geer, J. G. (1989). Nominating presidents: An evaluation of voters and primaries. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Gerken, H. K., & Rand, D. B. (2010). Creating better heuristics for the presidential primary: The citizen assembly. Political Science Quarterly, 125(2), 233–253.

Gopoian, J. D. (1982). Issue preferences and candidate choice in presidential primaries. American Journal of Political Science, 26(3), 523–546.

Ha, S. E., & Lau, R. R. (2010). Personality traits and correct voting. (under review).

Jackman, S., & Vavreck, L. (2009). Constructing the 2007–2008 Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project Sample. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University.

Jackman, S., & Vavreck, L. (2011). Cosmopolitanism. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University.

Jones-Correa, M., & Walker, A. (2011). Primary voting and general election turnout. In Paper presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, 31 Mar–3 Apr 2011.

Kam, C. D. (2005). Who toes the party line? Cues, values, and individual differences. Political Behavior, 27(2), 163–182.

Kamarck, E. C. (2009). Primary politics: How presidential candidates have shaped the modern nominating system. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Kaufman, K. M., Gimpel, J. G., & Hoffman, A. H. (2003). A promise fulfilled? Open primaries and representation. Journal of Politics, 65(2), 457–476.

Kenney, P. J., & Rice, T. W. (1994). The psychology of political momentum. Political Research Quarterly, 47(4), 923–938.

Kinder, D. R. (1998). Communication and opinion. In Annual review of political science (Vol. 1, pp 167–197). Stanford, CA: Annual Reviews.

Lau, R. R. (2003). Models of decision making. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 19–59). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lau, R. R., Andersen, D. J., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2008). An exploration of correct voting in recent U.S. presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science, 52(2), 395–411.

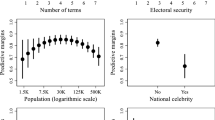

Lau, R.R., Patel, P., Fahmy, D., & Kaufman, R. (2012). Correct voting across 33 Democracies (under review).

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (1997). Voting correctly. American Political Science Review, 91(3), 585–599.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 951–971.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). How voters decide: Information processing during election campaigns. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lodge, M., & Hamill, R. (1986). A partisan schema for political information processing. American Political Science Review, 80(2), 505–519.

Mann, T. E. (2009). Is this any way to pick a president? Lessons from 2008. In S. S. Smith & M. J. Springer (Eds.), Reforming the presidential nomination process. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Marshall, T. R. (1984). Issues, personalities, and presidential primary voters. Social Science Quarterly, 65(3), 750–760.

Mayer, W. G. (2000). In pursuit of the White House 2000: How we choose our presidential nominees. Chatham, NJ: Chatham House.

Nisbett, R. E., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Norrander, B. (1986). Selective participation: Presidential primary voters as a subset of general election voters. American Politics Quarterly, 14(1), 35–53.

Norrander, B. (1989). Ideological representativeness of presidential primary voters. American Journal of Political Science, 33(3), 570–587.

Norrander, B. (2006). The attrition game: Initial resources, initial contests and the exit of candidates during the US presidential primary season. British Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 487–508.

Patel, P. (2010). The effect of institutions on correct voting. PhD Dissertation, Rutgers University.

Patterson, T. E. (2009). Voter participation: Records galore this time, but what about next time? In S. S. Smith & M. J. Springer (Eds.), Reforming the presidential nomination process. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Paulson, A. (2009). Party change and the shifting dynamics in presidential nominations: The Lessons of 2008. Polity, 41(3), 312–330.

Polsby, N., & Wildavsky, A. (1971). Presidential elections: Strategies of American electoral politics (3rd ed.). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Polsby, N., Wildavsky, A., & Hopkins, D. A. (2008). 1971. Presidential elections: Strategies and structures of American politics (12th ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Rabinowitz, G., & MacDonald, S. E. (1989). A directional theory of issue voting. American Political Science Review, 83(1), 93–121.

Redlawsk, D. P., Tolbert, C. J., & Donovan, T. (2011). Why Iowa? How caucuses and sequenced primaries improve the presidential nomination process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rickershauser, J., & Aldrich, J. H. (2007). It’s the electability, stupid’—or maybe not? electability, substance, and strategic voting in presidential primaries. Electoral Studies, 26(2), 371–380.

Ridout, T. N., & Rottinghaus, B. (2008). The importance of being early: Presidential primary front-loading and the impact of the proposed western regional primary. PS: Political Science & Politics, 41(1), 123–128.

Sabato, L. J. (2009). Picking presidential nominees: Time for a new regime. In S. S. Smith & M. J. Springer (Eds.), Reforming the presidential nomination process. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Sears, D. O., & Henry, P. J. (2005). Over thirty years later: A contemporary look at symbolic racism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 95–150.

Shafer, B. E. (1983). Quiet revolution: The struggle for the Democratic Party and the shaping of post-reform politics. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Williams, D. C., Weber, S. J., Haaland, G. A., Mueller, R. H., & Craig, R. E. (1976). Voter decisionmaking in a primary election: An evaluation of three models of choice. American Journal of Political Science, 20(1), 37–49.

Wright, G. C. (2009). Rules and the ideological character of primary electorates. In S. S. Smith & M. J. Springer (Eds.), Reforming the presidential nomination process. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Scott McKee and other panelists for their comments on an earlier version of this paper, and David Redlawsk for a very careful reading and several excellent ideas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Details of Constructing Correct Voting Measures

Appendix: Details of Constructing Correct Voting Measures

Four conceptually distinct sets of items go into the calculation of candidate “utility scores” that determine which candidate best represents a respondent’s own political values and priorities, and therefore which candidate a respondent “should” support in the primary election—policy stands, candidate-group connections, “electability” beliefs, and personality traits.Footnote 12 In every case we accept survey respondent’s reports of their own values and priorities, but try to find some semi-objective expert judgment about how closely each candidate actually “fits” those same values and priorities.

First, the survey asked respondent’s to place themselves and the major presidential candidates on five policy scales: a question about illegal immigrants, a question about government health care, a question about increasing taxes on the rich, a question about the war in Iraq, and an overall liberal-conservative scale. I relied on the mean ratings of expert respondents (those scoring in the top quarter of the distribution of political knowledge) to determine where the candidate’s stood on these issues. Respondents were also asked their opinion about the circumstances under which abortion should be legal, whether we should take action to slow climate change or protect jobs instead, how strongly they favored capital punishment, whether gay couples should be allowed to have legalized civil unions, and whether gays and lesbians should be allowed to adopt children; but they were never asked to place the major presidential candidates on those same issues. I therefore recruited a separate panel of experts (seven graduate students) to place these candidates on these five additional policy scales after reading an extensive file of information about the candidates’ actual stands on these issues. I used the mean responses of these seven experts as an objective reading of where the candidate’s stood on these five additional issues so that I could calculate agreement with the candidates on these five additional issues. Table 2 reports the “objective” candidate placement scores calculated for each candidate on each issue.

I then calculated each respondent’s proximity to each candidate on these issues.Footnote 13 The policy proximity scores were reversed (so that policy agreement is scored high) and rescaled to vary between −1 and +1, and then added to each candidate’s utility score. These policy agreement scores only factor into the candidate utility ratings for respondents who cared enough about an issue to report a position on it.

Respondents were also asked to indicate how well three positive traits (strong leader, trustworthy, has the right experience) described each candidate. I assume that everyone universally prefers strong, trustworthy, and experienced leaders. Responses to these questions were recoded to range between −1 “Not Well at All” to +1 “Extremely Well.” I again relied on the mean ratings of our expert respondents, and added these three ratings to each candidates utility score, but again only if respondents showed that they cared enough about these attributes that they answered the questions. These “objective” trait scores are reported at the bottom of Table 2.

To estimate candidate-group linkages, I considered whether a majority of (expert) members of 11 easily-identifiable social groups—men, women, blacks, whites, Latinos, the working class, rich people, Southerners, born-again Christians, Mormons, Muslims—voted for any particular candidate in either party’s primary. This procedure assumes that politically expert members of these social groups are able to ascertain important (linked-fate?) candidate-group linkages that are independent of policy stands. Empirically, there were only two such linkages, between Barack Obama and black Democrats, and between Mitt Romney and Mormon Republicans. I therefore created dummy variables representing membership in these two demographic categories, and added them to the utility scores associated with Obama or Romney, respectively.

An important consideration for voters in their party’s nomination contests is how “electable” the different candidates are—that is, how likely they are to win November’s general election campaign. CCAP respondents were asked this question about both parties’ candidates in the baseline and January waves of interviews, and just about Clinton and Obama in the March interview. No consensus had developed among experts in either party about which candidate was the most electable until the March wave, when a large majority of experts believed Obama was much more likely to win in November than Clinton. This did not give me much to work with.Footnote 14 Instead, I relied on the mean results of all survey questions (as reported by Real Clear Politics.com) pitting each viable Democrat against each viable Republican. I broke the nomination campaign into ten distinct periods, and calculated the average margin (across all surveys conducted during that period) by which each candidate would win or lose (“if the election were today”) against each remaining candidate from the other party. The mean of these average margins (averaging across all possible opponents) is the “electability” of that candidate during that time period. The data for all 8 candidates are reported in Table 3. I again normalized these electability scores within party so that they had a maximum range of −1 to +1 across the entire nomination process.

An unweighted sum measure of candidate utility is computed by simply adding together these 15 different criteria of judgement for each of the major candidates competing for their party’s nomination—Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, and Barack Obama on the Democratic side, Rudy Guiliani, Mike Huckabee, John McCain, Mitt Romney, and Fred Thompson, on the Republican side. Similarly, an unweighted mean measure of candidate utility is computed by averaging together these different criteria of judgement for each of the major candidates. Many respondents do not provide valid responses on all of these criteria of judgment, of course, but we use as many as we can in calculating the candidate utility scores. With the exception of the candidate-group linkages, however, if a criterion of judgment is available for one candidate it is available for all candidates.

The above procedure treats all 15 criteria of judgment as if they are equally important—a good first approximation, but one my intuitions suggest does not match reality for most people. I also devised simple measures of how important each criterion was to each respondent. People were asked to express an opinion on numerous occasions for almost all of these different criteria of judgment, either their own opinion on an issue across multiple waves of the study, or their beliefs about where different candidates stand on an issue or how a particular trait would apply to different candidates, or both. Thus it was almost always possible to compute implicit “importance” weights for each of the criteria of judgment—simply the proportion of relevant questions on which a respondent provided a valid response. A weighted sum measure of candidate utility is computed for each of the eight candidates by multiplying each criterion of judgment by its importance weight and then summing across these 15 products. An weighted mean measure candidate utility is computed for each candidate by averaging together the 15 different (criterion × importance weight) products.

The method described above treats each distinct consideration equally, but as described above I also considered the possibility that electability considerations should be counted more that once (in fact, up to ten times). The analysis in Table 1 utilizes the weighted-sum measure with electability counted three times, but the results are pretty much the same if we use any of the other three operationalizations of correct voting, and count electability less.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lau, R.R. Correct Voting in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Nominating Elections. Polit Behav 35, 331–355 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-012-9198-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-012-9198-9